Stephen Gallagher's Blog, page 29

October 7, 2012

Thy Kingdom's Coming

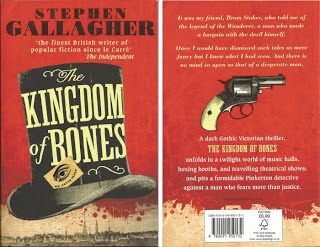

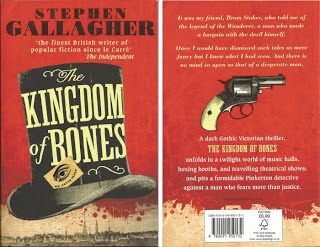

I got a present at Fantasycon last weekend; the Ebury publicity team had brought along an advance copy of the UK paperback of The Kingdom of Bones, and handed it to me at the launch of Random House's new Del Rey imprint.

It is cool.

The cover is by Headdesign, who provided art for the current set of Ian Fleming's James Bond novels from Vintage. The back of the jacket features Sebastian Becker's Bulldog revolver.

As a bonus you get the opening chapters of The Bedlam Detective, the Becker-led follow-up. That one's scheduled for May 2013.

But this one's is available from December 6th. Just in time for... well, you know the drill.

It is cool.

The cover is by Headdesign, who provided art for the current set of Ian Fleming's James Bond novels from Vintage. The back of the jacket features Sebastian Becker's Bulldog revolver.

As a bonus you get the opening chapters of The Bedlam Detective, the Becker-led follow-up. That one's scheduled for May 2013.

But this one's is available from December 6th. Just in time for... well, you know the drill.

Published on October 07, 2012 04:26

October 6, 2012

The Entitlement Thing

The magazine Doctor Who Monthly runs a readers' poll every season. This year, one reader couldn't even wait until the end of the run before sharing. He gave every story the lowest possible mark ('Awful'), including those he hadn't seen. He hated every villain that wasn't a Dalek, and called for Matt Smith to be replaced and Steven Moffat to leave the show. Favourite special effect? "Not interested". Favourite line of dialogue? "None".

Editor Tom Spilsbury won't give any details, but did say that the reader is in his mid-40s. Now, I'm not saying there's anything wrong with a middle-aged man watching Doctor Who. It's a show for the kid in us all, and that's one of the reasons for its success. But anywhere past your teens and you're not the target audience, you're a guest. A welcome guest, for sure. But a guest needs to know how to behave.

There are aspects of the show that I think work well and others that rub me up the wrong way (coughRiverSongcough) but I wouldn't dream of getting exercised over them, nor of demanding that the show be retuned to my preferences. We can all have an opinion about what works and what doesn't but when it comes to what goes in, the young audience is the one that matters most.

I'll confess my unease at the recent BBC-backed convention that discouraged children from attending. It wasn't a cultural studies symposium, it was a fan convention. But an adults-only Who feels... wrong. Take the kids out of the equation, and it's like messing with the gravitational balance of the Whoniverse. To me the most joyous part about New Who is seeing adults and kids together, parents sharing and passing on their renewed sense of wonder, a cameraderie that crosses age barriers. Those adults who gather in pubs to discuss it amongst themselves are connecting over something that started inside them long ago.

If it's going down well with the kids in a way that doesn't suit some adults, that's a pity but it's not for us to hijack it, nor to pester the driver by clamouring for his personal attention. When the kids are turning away, that's when it becomes a serious matter for the showrunner to ponder. And it's bad enough having to deal with notes from executives, without viewers trying to get in on the act. When it comes to someone else's TV show I consider myself a consumer, not a stakeholder, and for very good reason. I don't seek to be given exactly what I want. I'm looking for discovery. The risk of disappointment is the necessary downside of wonder.

And disappointment seems to come very easily to many people, these days, with every new genre piece being released to the sound of sharpening knives. Our culture has become like a birthing pool full of crocodiles. There was a time when the response to new material was to invest in it, meet it halfway, go all the way to find something to love in it, should it happen to be a Plan 9 or a Robot Monster.

Now, like the twerp who logs in to Amazon and one-stars every piece of PC software because it won't run on his Mac, the default setting seems to be one of outrage that our specific expectations haven't been met.

And speaking as someone who spent a childhood lost in awe, oblivious to wires, zips, obvious model work, corny dialogue, and stories that didn't always make sense, I think we're the poorer for it.

Editor Tom Spilsbury won't give any details, but did say that the reader is in his mid-40s. Now, I'm not saying there's anything wrong with a middle-aged man watching Doctor Who. It's a show for the kid in us all, and that's one of the reasons for its success. But anywhere past your teens and you're not the target audience, you're a guest. A welcome guest, for sure. But a guest needs to know how to behave.

There are aspects of the show that I think work well and others that rub me up the wrong way (coughRiverSongcough) but I wouldn't dream of getting exercised over them, nor of demanding that the show be retuned to my preferences. We can all have an opinion about what works and what doesn't but when it comes to what goes in, the young audience is the one that matters most.

I'll confess my unease at the recent BBC-backed convention that discouraged children from attending. It wasn't a cultural studies symposium, it was a fan convention. But an adults-only Who feels... wrong. Take the kids out of the equation, and it's like messing with the gravitational balance of the Whoniverse. To me the most joyous part about New Who is seeing adults and kids together, parents sharing and passing on their renewed sense of wonder, a cameraderie that crosses age barriers. Those adults who gather in pubs to discuss it amongst themselves are connecting over something that started inside them long ago.

If it's going down well with the kids in a way that doesn't suit some adults, that's a pity but it's not for us to hijack it, nor to pester the driver by clamouring for his personal attention. When the kids are turning away, that's when it becomes a serious matter for the showrunner to ponder. And it's bad enough having to deal with notes from executives, without viewers trying to get in on the act. When it comes to someone else's TV show I consider myself a consumer, not a stakeholder, and for very good reason. I don't seek to be given exactly what I want. I'm looking for discovery. The risk of disappointment is the necessary downside of wonder.

And disappointment seems to come very easily to many people, these days, with every new genre piece being released to the sound of sharpening knives. Our culture has become like a birthing pool full of crocodiles. There was a time when the response to new material was to invest in it, meet it halfway, go all the way to find something to love in it, should it happen to be a Plan 9 or a Robot Monster.

Now, like the twerp who logs in to Amazon and one-stars every piece of PC software because it won't run on his Mac, the default setting seems to be one of outrage that our specific expectations haven't been met.

And speaking as someone who spent a childhood lost in awe, oblivious to wires, zips, obvious model work, corny dialogue, and stories that didn't always make sense, I think we're the poorer for it.

Published on October 06, 2012 14:18

October 5, 2012

Short Horror?

My psychology lecturer friend is looking for a horror short of around 15-20 minutes to screen to a bunch of subjects as part of an experiment to test their recall. She needs to be able to show formal permission for its use, so she can't just nick a scene from a DVD.

If you've made a suitable short film and you're willing to make it available, tweet me a link @brooligan or use the email form on my contact page.

I'll pass on anything you send. Unless it's naked pictures of your bits.

We have some standards, here.

UPDATE: Thanks to all who responded. I've passed along the links. She now has to contend with her ethics committee...

If you've made a suitable short film and you're willing to make it available, tweet me a link @brooligan or use the email form on my contact page.

I'll pass on anything you send. Unless it's naked pictures of your bits.

We have some standards, here.

UPDATE: Thanks to all who responded. I've passed along the links. She now has to contend with her ethics committee...

Published on October 05, 2012 03:13

September 24, 2012

The LFS 'Running the Show' TV Drama Series Event

At the end of my previous post on people in writing careers without any ideas to drive them, I mentioned an entry in Little Miss Brooligan's blog

said the Actress to the Vicar

on the subject of writers and writers' rooms. It's part of her coverage of Running the Show, an intensive day of sessions with British producers and American showrunners organised in July by the London Film School.

Speakers included Tony Garnett, Stephen Garrett of Kudos, and X-Files alumnus Frank Spotnitz whose new show, Hunted, is an international venture involving Kudos, the BBC, and HBO.

From the notes:

Speakers included Tony Garnett, Stephen Garrett of Kudos, and X-Files alumnus Frank Spotnitz whose new show, Hunted, is an international venture involving Kudos, the BBC, and HBO.

From the notes:

HUNTED – A new co-pro between BBC and HBO – there are two different cuts for broadcast on each (ie HBO has a lot more nudity!) It was written using a writers’ room, unusually for the UK. Series creator and showrunner Frank Spotnitz brought along his team of writers and explained how the process worked – he wrote the pilot solo, then met with his writers and they discussed where the characters & plot might go over the course of the series. Then they each took an episode and wrote it, with Frank rewriting all of them to varying degrees. It was a very collaborative process though. They treated the episodes like mini movies, deciding for each a particular movie that would serve as a ‘model’ for the tone and pace of the episode. During production, the writers were on set a lot, and also invited to be involved in the edit – they were involved at every stage.Other topics covered include ‘Trojan Horse’ drama, smuggling in originality while making a project seem like something familiar, and the high global demand for English-language drama. You can find the full piece here.

Published on September 24, 2012 08:18

Writers Write. Don't They?

A couple of weeks ago I had a catch-up lunch with someone I worked with a few years back. She was a script editor then and she's an executive producer now, but it wasn't a pitching opportunity, more of a comrades' get-together.

(I was going to say 'old comrades', but, you know, that would make her sound old, and she isn't.)

(Which I think should cover me if she reads this.)

I was aware of a couple of the jobs she'd done since we'd last met, but she'd had about half a dozen, skipping from one company to another for a variety of reasons... a departing boss, a vanishing drama budget, and in one case a writer-killer actor that no one wants to work with more than once. Entitled performers, take note. Similarly, she was aware of some of my recent credits but not the stories behind them.

I was telling her about the four US pilots that to date I've pitched, sold, and that haven't been picked up (the number's a bit of a cheat because I sold one spec script twice), and the new ideas I'm working on, when she said, "You're nothing like the other writers I meet."

"Oh?" I said, wondering what was coming next. "How so?"

"They don't bring in ideas."

"Then, what do they talk about?"

"They're looking to us to give them something to work on."

I should add that the company she's with is a serious player, and no, don't ask me to tell you which company it is.

This notion of writers without ideas of their own seemed alien to me, but apparently there's a whole raft of them out there and she gets a lot of them through her door. They're professionals, making a living. Some of them will take an assignment only to deliver late because they got another job elsewhere and worked on that instead.

Who are they? I have no idea. We don't move in the same circles and I can't even imagine their mindset. There's a notion I picked up from Mike Newell when we were developing one of my novels for a feature (unmade) - that the working life is divided between personal projects and 'gigs'. You bring the same professionalism to each but they mean different things to you. The quality of work stays the same. Often it's possible to blur the line between the two, if you can make some personal investment in a template you didn't invent.

The best gigs sustain and entertain you but the personal projects are always there, awaiting their chance. You keep a running Wish List. Some you fall out of love with, or they pass their sell-by date, but then every now and again a new one gets added to the list. I've learned that if the market doesn't want your stuff today, don't despair. If you sit on the bank of the river for long enough, the body of the latest BBC1 controller will float by.

I wondered if this (to my mind) passive attitude is an unintended consequence of British TV's diversion of new writers into its soaps and returning dramas. Once upon a time, if a writer shone in a soap or in fringe theatre, they'd get a shot at a single play on a subject of their choice. That's how we got Dennis Potter, Jack Rosenthal, Joe Orton, Alan Plater, Arthur Hopcraft, Stephen Poliakoff; and if they then went on to do series work it would forever have their distinctive and individual signature on it.

Those slots - Play for Today, ITV Playhouse, Armchair Theatre, The Wednesday Play, in retrospect the R&D division of British TV drama - no longer exist. A new writer today is most likely to be inducted into a world of long-term storylines and given episode structures. Which sounds to me like a bit of a honeytrap - you're offered a living but you give up your voice, like The Little Mermaid.

But I don't really know because I've never worked that way. I have worked in the American Writers' Room system, where a showrunner plus staff work together to give an authored consistency to twenty-two hours of television in a nine-month burst. But every one of those staffers has a spec pilot on their netbook and their eye on a showrunner's chair of their own. As did, in my experience, the writers' assistant, the showrunner's PA, and the script co-ordinator.

Have we bred the fire out of a generation of TV writers? On Said the Actress to the Vicar this blog comment from former Holby and Crossroads producer Yvonne Grace suggests that there's a happier medium in a reality of which I've no experience.

Whatever the case, the thought that there are gigs-only writers out there, looking to be hired but with nothing personal on their wish lists, came as a surprise to me.

(I was going to say 'old comrades', but, you know, that would make her sound old, and she isn't.)

(Which I think should cover me if she reads this.)

I was aware of a couple of the jobs she'd done since we'd last met, but she'd had about half a dozen, skipping from one company to another for a variety of reasons... a departing boss, a vanishing drama budget, and in one case a writer-killer actor that no one wants to work with more than once. Entitled performers, take note. Similarly, she was aware of some of my recent credits but not the stories behind them.

I was telling her about the four US pilots that to date I've pitched, sold, and that haven't been picked up (the number's a bit of a cheat because I sold one spec script twice), and the new ideas I'm working on, when she said, "You're nothing like the other writers I meet."

"Oh?" I said, wondering what was coming next. "How so?"

"They don't bring in ideas."

"Then, what do they talk about?"

"They're looking to us to give them something to work on."

I should add that the company she's with is a serious player, and no, don't ask me to tell you which company it is.

This notion of writers without ideas of their own seemed alien to me, but apparently there's a whole raft of them out there and she gets a lot of them through her door. They're professionals, making a living. Some of them will take an assignment only to deliver late because they got another job elsewhere and worked on that instead.

Who are they? I have no idea. We don't move in the same circles and I can't even imagine their mindset. There's a notion I picked up from Mike Newell when we were developing one of my novels for a feature (unmade) - that the working life is divided between personal projects and 'gigs'. You bring the same professionalism to each but they mean different things to you. The quality of work stays the same. Often it's possible to blur the line between the two, if you can make some personal investment in a template you didn't invent.

The best gigs sustain and entertain you but the personal projects are always there, awaiting their chance. You keep a running Wish List. Some you fall out of love with, or they pass their sell-by date, but then every now and again a new one gets added to the list. I've learned that if the market doesn't want your stuff today, don't despair. If you sit on the bank of the river for long enough, the body of the latest BBC1 controller will float by.

I wondered if this (to my mind) passive attitude is an unintended consequence of British TV's diversion of new writers into its soaps and returning dramas. Once upon a time, if a writer shone in a soap or in fringe theatre, they'd get a shot at a single play on a subject of their choice. That's how we got Dennis Potter, Jack Rosenthal, Joe Orton, Alan Plater, Arthur Hopcraft, Stephen Poliakoff; and if they then went on to do series work it would forever have their distinctive and individual signature on it.

Those slots - Play for Today, ITV Playhouse, Armchair Theatre, The Wednesday Play, in retrospect the R&D division of British TV drama - no longer exist. A new writer today is most likely to be inducted into a world of long-term storylines and given episode structures. Which sounds to me like a bit of a honeytrap - you're offered a living but you give up your voice, like The Little Mermaid.

But I don't really know because I've never worked that way. I have worked in the American Writers' Room system, where a showrunner plus staff work together to give an authored consistency to twenty-two hours of television in a nine-month burst. But every one of those staffers has a spec pilot on their netbook and their eye on a showrunner's chair of their own. As did, in my experience, the writers' assistant, the showrunner's PA, and the script co-ordinator.

Have we bred the fire out of a generation of TV writers? On Said the Actress to the Vicar this blog comment from former Holby and Crossroads producer Yvonne Grace suggests that there's a happier medium in a reality of which I've no experience.

Whatever the case, the thought that there are gigs-only writers out there, looking to be hired but with nothing personal on their wish lists, came as a surprise to me.

Published on September 24, 2012 07:08

August 5, 2012

Fiction Reboot

A couple of weeks ago I answered a few interview questions from novelist/academic researcher/teacher Brandy Schillace, and the results are now online. I spouted stuff like:

A couple of weeks ago I answered a few interview questions from novelist/academic researcher/teacher Brandy Schillace, and the results are now online. I spouted stuff like:"Through my teens I read classic science fiction and ’60s British thriller writers. Then I had the advantage of a very solid three years of education in English Literature that opened up new avenues to me, from the medieval mindset to the poetry of Thomas Hardy. I think the point is that as a reader I had a big, big net, and a special fascination with popular fiction. I can remember buying Westerns and Romance novels, neither of which were of particular interest to me but I felt driven to find out what was going on in that kind of writing. I looked at William Goldman and Michael Crichton and saw that it was possible to be both a novelist and a screenwriter; Goldman kept the distinction clear and Crichton’s later, less substantial work showed what can happen when you don’t, so I learned from both of them."and

"Research is nothing more than expanded observation and as such, it’s key to all creation. Art’s about insight, and you can’t offer insight into nothing. Research is about continuing to write with authority after you’ve detected the limits of what you know."More dazzling autobiography and Secrets of the Universe here.

And while you're visiting, dig around a little. Dr Schillace's interest in the intersection of science, medicine and literature give her obsessions and researches an inevitably Gothic tint. Her published academic work covers areas of psychology, neurology, weird science and reproduction; here's a podcast recorded in the Wellcome Collection's club room, in which she discusses recent work on syphilis and Dracula, while if your imagination isn't piqued by her search across Europe for the Labour Device, an eighteenth-century "mechanical phantom used in the teaching of male midwives", then I don't know what would do it.

Published on August 05, 2012 03:02

July 26, 2012

CarNivorous

We were driving from Phoenix to Tuscon when the car passed over the body of a flattened skunk. This was a long, straight Arizona road and it cut across the desert like an arrow. We didn't know it was a skunk at the time, but we found that out soon enough. There was a few seconds' delay as the air from the intakes made its way through the cooling system. Then it hit us.

After that I steered wide of roadkill whenever I saw it coming, and as a result I suppose I became more aware of just how much of it there was. The road was like a suicide strip for small mammals. The desert was anything but deserted.

At the end of every day's driving, I'd have to clean off all the splattered bugs that had baked onto the windscreen. There were a lot of those, as well. Some of them had hit like bullets but most of them were just there, a silent accumulation like so much airborne plankton. They weren't just on the glass, they were all over the front end of the car.

It seemed like a shame.

And it felt like a waste.

Because that's when I started to think: wouldn't it be great if the car could make use of all that protein? I mean, it's out there and it's free and it dies anyway. Combustion engines have been around for barely more than a century, and already they've sucked half of the oil out of the planet. Living things have been around for hundreds of millions of years, and they just renew and get more numerous. Look at Birmingham.

I'm telling you, this is the way ahead.

It'll need some bright spark to come up with a functional design, of course. I picture it as some kind of a scoop at the front of the car and a big, flexible bag underneath, for digestion. It would have to be flexible because roadkill comes in all kinds of awkward sizes. Once it's in the bag, we could get really tricky and imagine it being broken down into endless complex molecules fuelling micro-engines throughout the vehicle's body. This would call for corrosive stomach juices made by designer enzymes, self-renewing, and some kind of a teflon lining to contain the process.

Or we could leave that for future generations of carnivorous cars and concentrate for now on getting heat out of the material. A TV documentary on Spontaneous Human Combustion showed that with one Coronation Street fan and a careless match you can generate intense heat energy over several hours, if the body's wearing surgical tights and a cardigan. Experimentation with our teflon lining should lead us to reproduce the 'cardigan effect' and before we knew it we'd have a road monster with real fire in its belly.

I'd give the scoop some maneuverability and the car a rudimentary predatory intelligence, so it could spot targets and react to them. I'd see this as a matter of simple humanity; a rabbit caught by the edge of the scoop and flung to the roadside is a life wasted. At the other end of the system, the exhaust pipe would be replaced by a rectum that would open and close like that gun barrel in the opening credits of the Bond movies. Waste products would probably be minimal and could be returned to the land, after the teeth had been sieved out.

All this is fine for places where the roadkill's thick on the ground, so to speak, but what about the UK?

Well, probably nothing much will change. While American cars are being fuelled by moose and coyote, we'll be puttering around in our little hedgehog-and-pigeon runabouts. But why restrict our thinking to roadkill? Apart from an obvious use for household scraps and leftovers, there are all those mad cow carcases and the entire European beef mountain to be used up. Not to mention hospital waste.

The petrol engine would be history. Who'd pay for expensive fuel when you could run down wildlife for free? But this is where the scenario starts to darken. Human nature being what it is, I can imagine plenty of people who'd think nothing of grabbing next door's cat when they thought no-one was looking, and stuffing it into the intake for some free mileage. Anyone out walking the dog had better be ready to dodge and run.

Then, as time moves on, hitch-hikers become fair game. Police speeding to the scene of any big road smash find passing motorists fighting over the bodies. Deceased relatives are fed to the family car with cries of, "It's what he would have wanted."

Meanwhile, those predatory instincts begin to evolve through successive generations of design. You keep 'em fed, or they turn on you. The wheel spins in your hand at the scent of a pedestrian. It's a race to make it safely out of the garage at the end of a journey.

Then late one night on a lonely road, you hear a rattle coming from the front of the car. It sounds expensive, so you stop to take a look. You crouch down in front to take a look. You find nothing... but it's already too late.

I'm telling you. It's a Mad Max future for us, whichever way we go.

First published in T3 Magazine

After that I steered wide of roadkill whenever I saw it coming, and as a result I suppose I became more aware of just how much of it there was. The road was like a suicide strip for small mammals. The desert was anything but deserted.

At the end of every day's driving, I'd have to clean off all the splattered bugs that had baked onto the windscreen. There were a lot of those, as well. Some of them had hit like bullets but most of them were just there, a silent accumulation like so much airborne plankton. They weren't just on the glass, they were all over the front end of the car.

It seemed like a shame.

And it felt like a waste.

Because that's when I started to think: wouldn't it be great if the car could make use of all that protein? I mean, it's out there and it's free and it dies anyway. Combustion engines have been around for barely more than a century, and already they've sucked half of the oil out of the planet. Living things have been around for hundreds of millions of years, and they just renew and get more numerous. Look at Birmingham.

I'm telling you, this is the way ahead.

It'll need some bright spark to come up with a functional design, of course. I picture it as some kind of a scoop at the front of the car and a big, flexible bag underneath, for digestion. It would have to be flexible because roadkill comes in all kinds of awkward sizes. Once it's in the bag, we could get really tricky and imagine it being broken down into endless complex molecules fuelling micro-engines throughout the vehicle's body. This would call for corrosive stomach juices made by designer enzymes, self-renewing, and some kind of a teflon lining to contain the process.

Or we could leave that for future generations of carnivorous cars and concentrate for now on getting heat out of the material. A TV documentary on Spontaneous Human Combustion showed that with one Coronation Street fan and a careless match you can generate intense heat energy over several hours, if the body's wearing surgical tights and a cardigan. Experimentation with our teflon lining should lead us to reproduce the 'cardigan effect' and before we knew it we'd have a road monster with real fire in its belly.

I'd give the scoop some maneuverability and the car a rudimentary predatory intelligence, so it could spot targets and react to them. I'd see this as a matter of simple humanity; a rabbit caught by the edge of the scoop and flung to the roadside is a life wasted. At the other end of the system, the exhaust pipe would be replaced by a rectum that would open and close like that gun barrel in the opening credits of the Bond movies. Waste products would probably be minimal and could be returned to the land, after the teeth had been sieved out.

All this is fine for places where the roadkill's thick on the ground, so to speak, but what about the UK?

Well, probably nothing much will change. While American cars are being fuelled by moose and coyote, we'll be puttering around in our little hedgehog-and-pigeon runabouts. But why restrict our thinking to roadkill? Apart from an obvious use for household scraps and leftovers, there are all those mad cow carcases and the entire European beef mountain to be used up. Not to mention hospital waste.

The petrol engine would be history. Who'd pay for expensive fuel when you could run down wildlife for free? But this is where the scenario starts to darken. Human nature being what it is, I can imagine plenty of people who'd think nothing of grabbing next door's cat when they thought no-one was looking, and stuffing it into the intake for some free mileage. Anyone out walking the dog had better be ready to dodge and run.

Then, as time moves on, hitch-hikers become fair game. Police speeding to the scene of any big road smash find passing motorists fighting over the bodies. Deceased relatives are fed to the family car with cries of, "It's what he would have wanted."

Meanwhile, those predatory instincts begin to evolve through successive generations of design. You keep 'em fed, or they turn on you. The wheel spins in your hand at the scent of a pedestrian. It's a race to make it safely out of the garage at the end of a journey.

Then late one night on a lonely road, you hear a rattle coming from the front of the car. It sounds expensive, so you stop to take a look. You crouch down in front to take a look. You find nothing... but it's already too late.

I'm telling you. It's a Mad Max future for us, whichever way we go.

First published in T3 Magazine

Published on July 26, 2012 10:23

June 18, 2012

How Do I Get My Script Read?

"Any advice for getting a script read by some influential people?" A question asked of me via Twitter that's impossible to answer in 140 characters. But here's the digest version.

My experience is that "influence" is mostly a public illusion of power, and it's no subsitute for the actual ability to get stuff made, whether it's for film or TV. Those who can get stuff made are an ever-changing crowd, its composition determined by the ebb and flow of personal or corporate fortune.

Some of the players are obvious. Ridley Scott can get stuff made. Kudos can get stuff made. For more names - you need to study credits, read the trades.

And even Ridley Scott moves in a world where he's juggling with what's possible for him to achieve at any given time. I'm sure there are plenty of projects he'd love to be working on. But the ones he can get off the ground are those that the market wants from him right then. He'll have more choices than most, but you can be sure he doesn't operate by personal whim.

So, the good news and bad news. The good news is that the players are always on the lookout for new material to keep them in the game. The bad news - I call it bad news, actually it's just a fact of life - is that they get offered so much that each has to employ a fairly ruthless filtering system to cope with it.

But it's a filtering system, not an impervious wall. Bear in mind that it's designed to locate exactly the kind of thing the company's currently looking for - business research, not public service.

Many companies. All different needs.

The first stage of the filter is usually an 'agented or solicited submissions only' policy. That's basically saying, "No cold callers". The expectation is that an agent will only submit material that's appropriate and of professional quality. Some agents shake that faith on a daily basis, I'm told.

A solicited submission is one for which the company has opened the door. A tiny percentage of these come through some privileged contact, giving mind-fuel to the paranoid. But once received, they'll go through the same Darwinian in-house procedure as all the rest, where nepotism or special access count for nothing.

I've never seen a better insight into that process than the one given here by mega-producer Gavin Polone. He's writing about the industry in the US and you can scale it down a few notches for the UK, while bearing in mind that the number of outlets is proportionately smaller.

(and if you scroll down the comments, it's fairly easy to distinguish the "Hollywood sucks" contributors from the professionally aware.)

You can get a solicited read for your script even if you don't have an agent. It comes down to this: give them a reason to be interested in you. Then they may have a reason to open the door, and to stand the expense of giving you serious consideration. Make your first mark. A short film, a home-made audio podcast, a bare-stage fringe two-hander with a couple of mates, a few short stories with a respected small press, a YouTube channel with a creditable following.

Something modest, achieved well, counts for more than something ambitious, achieved badly.

Then - enquire. The classic query letter. But draw your promise to their attention (and have the wit to research the company so that your material is a match for their needs, and your enquiry goes to the right person).

99% fail right there, which is a Good Thing because it thins the field for someone like you. More than three short paragraphs, and you've probably blown it. But if you come over as a sensible adult with a professional attitude, and your project is in their ballpark, you may be invited to submit. If not, don't attempt to turn it into a conversation. Move on. And meanwhile be planning your next short, your next fringe piece... maybe get on a Script Factory course, involve yourself in someone else's project. True creativity doesn't wait around for an outlet. Channel yours into growing that starter CV.

Every produced screenwriter that I know has followed some form of this path. Every one of them. You may hear tales of non-pros getting Hollywood breaks - I recall one about a taxi driver pitching a screenplay to his passenger in the course of a ride - but these are invariably more complex stories that have been shaped by some journalist into fairytale form.

My experience is that "influence" is mostly a public illusion of power, and it's no subsitute for the actual ability to get stuff made, whether it's for film or TV. Those who can get stuff made are an ever-changing crowd, its composition determined by the ebb and flow of personal or corporate fortune.

Some of the players are obvious. Ridley Scott can get stuff made. Kudos can get stuff made. For more names - you need to study credits, read the trades.

And even Ridley Scott moves in a world where he's juggling with what's possible for him to achieve at any given time. I'm sure there are plenty of projects he'd love to be working on. But the ones he can get off the ground are those that the market wants from him right then. He'll have more choices than most, but you can be sure he doesn't operate by personal whim.

So, the good news and bad news. The good news is that the players are always on the lookout for new material to keep them in the game. The bad news - I call it bad news, actually it's just a fact of life - is that they get offered so much that each has to employ a fairly ruthless filtering system to cope with it.

But it's a filtering system, not an impervious wall. Bear in mind that it's designed to locate exactly the kind of thing the company's currently looking for - business research, not public service.

Many companies. All different needs.

The first stage of the filter is usually an 'agented or solicited submissions only' policy. That's basically saying, "No cold callers". The expectation is that an agent will only submit material that's appropriate and of professional quality. Some agents shake that faith on a daily basis, I'm told.

A solicited submission is one for which the company has opened the door. A tiny percentage of these come through some privileged contact, giving mind-fuel to the paranoid. But once received, they'll go through the same Darwinian in-house procedure as all the rest, where nepotism or special access count for nothing.

I've never seen a better insight into that process than the one given here by mega-producer Gavin Polone. He's writing about the industry in the US and you can scale it down a few notches for the UK, while bearing in mind that the number of outlets is proportionately smaller.

(and if you scroll down the comments, it's fairly easy to distinguish the "Hollywood sucks" contributors from the professionally aware.)

You can get a solicited read for your script even if you don't have an agent. It comes down to this: give them a reason to be interested in you. Then they may have a reason to open the door, and to stand the expense of giving you serious consideration. Make your first mark. A short film, a home-made audio podcast, a bare-stage fringe two-hander with a couple of mates, a few short stories with a respected small press, a YouTube channel with a creditable following.

Something modest, achieved well, counts for more than something ambitious, achieved badly.

Then - enquire. The classic query letter. But draw your promise to their attention (and have the wit to research the company so that your material is a match for their needs, and your enquiry goes to the right person).

99% fail right there, which is a Good Thing because it thins the field for someone like you. More than three short paragraphs, and you've probably blown it. But if you come over as a sensible adult with a professional attitude, and your project is in their ballpark, you may be invited to submit. If not, don't attempt to turn it into a conversation. Move on. And meanwhile be planning your next short, your next fringe piece... maybe get on a Script Factory course, involve yourself in someone else's project. True creativity doesn't wait around for an outlet. Channel yours into growing that starter CV.

Every produced screenwriter that I know has followed some form of this path. Every one of them. You may hear tales of non-pros getting Hollywood breaks - I recall one about a taxi driver pitching a screenplay to his passenger in the course of a ride - but these are invariably more complex stories that have been shaped by some journalist into fairytale form.

Published on June 18, 2012 03:23