Stephen Gallagher's Blog, page 23

July 19, 2013

The Opinionated Writer, Part Two

Earlier this year I gave long answers to some very basic questions for a film student's diploma dissertation.

Is there a difference in writing for UK and US audiences, and if there is, what is it (cost, budget, more/less freedom)?

I don't think the audiences are that different, but I find that the commissioning cultures are. I much prefer dealing with the US, where they don't fanny around. There I've pitched a script in the morning and had a Yes before lunchtime. The energy level's higher and if something doesn't work out, it doesn't count against you. You've simply proved yourself a player. UK commissioners are unclear on what they want and indecisive over what they're shown, and they have no concept of the value of a fast No.

In the writing I don't really discriminate between US and UK because the stuff I do tends to work in either venue. Either that or I've always been a misplaced American TV writer at heart and that would explain why getting every one of my UK projects made has been like re-inventing the wheel. I like US pace and structure. To me it's all about witnessing things as they happen, not watching conversations about events.

Budget's not such an issue at the concept stage where the ideas set the agenda. The budget is drawn up on the script and obviously you look for savings, but the script came first. Once a show is under way then budget is a factor, because it's been set before the scripts are written. Every episode is scheduled for, say, 8 shooting days, with maybe 5 of them in the studio and 3 of them 'out'. In the studio you'll want to make maximum use of your standing sets, and on your 'out' days you'll want to combine locations to minimise time-consuming crew moves. I once had to lose a crowd scene in order to be able to afford a submarine. You can call that a limiting of freedom; to me it's just the way to what you want.

What are the differences between original material and adaptations?

With an adaptation you're spared the sweaty anxiety of the early stages where you have an idea, and you feel it's good, but you don't yet know if there's a form in which it will work. When you're adapting your own work or someone else's, that question's already been solved. You may need to come up with a radical reconception of form to take it from one medium to another, but the baseline is that the ideas fit together, they go somewhere, and there's a pool of characters and incidents to draw upon.

With an original, you first have to do all the work that gets you up to that baseline. For me it's the crucial part. It's satisfying but it's not enjoyable.

To be continued in Part 3Back to Part 1

Is there a difference in writing for UK and US audiences, and if there is, what is it (cost, budget, more/less freedom)?

I don't think the audiences are that different, but I find that the commissioning cultures are. I much prefer dealing with the US, where they don't fanny around. There I've pitched a script in the morning and had a Yes before lunchtime. The energy level's higher and if something doesn't work out, it doesn't count against you. You've simply proved yourself a player. UK commissioners are unclear on what they want and indecisive over what they're shown, and they have no concept of the value of a fast No.

In the writing I don't really discriminate between US and UK because the stuff I do tends to work in either venue. Either that or I've always been a misplaced American TV writer at heart and that would explain why getting every one of my UK projects made has been like re-inventing the wheel. I like US pace and structure. To me it's all about witnessing things as they happen, not watching conversations about events.

Budget's not such an issue at the concept stage where the ideas set the agenda. The budget is drawn up on the script and obviously you look for savings, but the script came first. Once a show is under way then budget is a factor, because it's been set before the scripts are written. Every episode is scheduled for, say, 8 shooting days, with maybe 5 of them in the studio and 3 of them 'out'. In the studio you'll want to make maximum use of your standing sets, and on your 'out' days you'll want to combine locations to minimise time-consuming crew moves. I once had to lose a crowd scene in order to be able to afford a submarine. You can call that a limiting of freedom; to me it's just the way to what you want.

What are the differences between original material and adaptations?

With an adaptation you're spared the sweaty anxiety of the early stages where you have an idea, and you feel it's good, but you don't yet know if there's a form in which it will work. When you're adapting your own work or someone else's, that question's already been solved. You may need to come up with a radical reconception of form to take it from one medium to another, but the baseline is that the ideas fit together, they go somewhere, and there's a pool of characters and incidents to draw upon.

With an original, you first have to do all the work that gets you up to that baseline. For me it's the crucial part. It's satisfying but it's not enjoyable.

To be continued in Part 3Back to Part 1

Published on July 19, 2013 03:52

July 17, 2013

The Opinionated Writer, Part One

Earlier this year I gave long answers to some very basic questions for a film student's diploma dissertation.

I had two aims in mind, beyond the obvious one of helping him out. One was that I'd eventually put the material online for general use (so other film students, take from this what you will and don't email asking me to write your essay for you).

The other involved the hope that I might inject a little contemporary awareness into academia, after hearing of a student on a script editing course being scoffed at for suggesting that the US TV writer's experience can be better than here. But she was right - those epic horror stories from LA-bruised Brits are not the norm.

I've a lot of friends, colleagues and Twitterpals in the business who work in areas that I don't, and usually in a piece like this I'd stop along the way to consider and qualify some of my remarks with them in mind. Here I just kind of charged on through. So if you want to take exception to anything, by all means do; and if you want to blog a riposte to any of these points, let me know and I may embed a link.

It's in four sections. The others are scheduled to appear over the next few days.

So here goes.

What are the differences between writing for TV and for film?

I have to break this into two parts because there's 1) the conceptual difference in the two dramatic forms, and then 2) the difference in working practice.

1) I've heard it said that if something remarkable happens to people once in in a lifetime then it's a movie, but if something remarkable happens to them every week then it's television. A film story fashions a universal myth out of its material. Television drama approaches the universal from another angle, taking the myth apart and finding the domestic details that build toward it. When you have nothing but the domestic details, to no ultimate purpose, you have a soap.

2) Most starting-out writers dream of selling a feature screenplay, but all the feature writers want to get into television where they'll have greater opportunities for expression and control. See Ted Griffin, Graham Yost, David Goyer. It wasn't always that way - TV used to be seen as a lesser medium with lower budgets and lesser ambitions - but that's changed. They've now become very different beasts. As feature budgets have grown, their choices have become safer and safer. In features the writer is required to serve the director's vision, and is a replaceable component. In TV - and especially in American TV - the director's job is to get the showrunner's vision onto the screen. The showrunner is an industry-trained writer in charge of a writing team and a production machine. He or she will most likely have conceived and pitched the idea to the network and written the pilot, although sometimes an experienced showrunner is hired to take charge of a series conceived by an inexperienced creator. The UK has yet to fully embrace the showrunner concept. In the UK writers are mostly shut out of production so they'll rarely have any hands-on production experience.

How much influence do producers have over your work?

The two equally valid answers are, none, and huge. None because, as a writer, the thing that gives you value is your unique point of view. If you don't have that, if you only ever write to assignment or chase the market, then you're aiming no higher than the second division. You should conceive your ideas with no thought of catering to anyone else. And huge because, once you find a producer who picks up on your point of view and believes that what you're doing is what he or she has been looking for, then you enter a partnership in which the other person steers. I've known that go well and I've known it go horribly wrong. They can hire a 'visual' director with no narrative gift, or one of the known 'writer-killers' who don't respect the script. They can miscast key roles. In a worst-case scenario they can replace you with an untalented friend.

To be continued in Part 2

I had two aims in mind, beyond the obvious one of helping him out. One was that I'd eventually put the material online for general use (so other film students, take from this what you will and don't email asking me to write your essay for you).

The other involved the hope that I might inject a little contemporary awareness into academia, after hearing of a student on a script editing course being scoffed at for suggesting that the US TV writer's experience can be better than here. But she was right - those epic horror stories from LA-bruised Brits are not the norm.

I've a lot of friends, colleagues and Twitterpals in the business who work in areas that I don't, and usually in a piece like this I'd stop along the way to consider and qualify some of my remarks with them in mind. Here I just kind of charged on through. So if you want to take exception to anything, by all means do; and if you want to blog a riposte to any of these points, let me know and I may embed a link.

It's in four sections. The others are scheduled to appear over the next few days.

So here goes.

What are the differences between writing for TV and for film?

I have to break this into two parts because there's 1) the conceptual difference in the two dramatic forms, and then 2) the difference in working practice.

1) I've heard it said that if something remarkable happens to people once in in a lifetime then it's a movie, but if something remarkable happens to them every week then it's television. A film story fashions a universal myth out of its material. Television drama approaches the universal from another angle, taking the myth apart and finding the domestic details that build toward it. When you have nothing but the domestic details, to no ultimate purpose, you have a soap.

2) Most starting-out writers dream of selling a feature screenplay, but all the feature writers want to get into television where they'll have greater opportunities for expression and control. See Ted Griffin, Graham Yost, David Goyer. It wasn't always that way - TV used to be seen as a lesser medium with lower budgets and lesser ambitions - but that's changed. They've now become very different beasts. As feature budgets have grown, their choices have become safer and safer. In features the writer is required to serve the director's vision, and is a replaceable component. In TV - and especially in American TV - the director's job is to get the showrunner's vision onto the screen. The showrunner is an industry-trained writer in charge of a writing team and a production machine. He or she will most likely have conceived and pitched the idea to the network and written the pilot, although sometimes an experienced showrunner is hired to take charge of a series conceived by an inexperienced creator. The UK has yet to fully embrace the showrunner concept. In the UK writers are mostly shut out of production so they'll rarely have any hands-on production experience.

How much influence do producers have over your work?

The two equally valid answers are, none, and huge. None because, as a writer, the thing that gives you value is your unique point of view. If you don't have that, if you only ever write to assignment or chase the market, then you're aiming no higher than the second division. You should conceive your ideas with no thought of catering to anyone else. And huge because, once you find a producer who picks up on your point of view and believes that what you're doing is what he or she has been looking for, then you enter a partnership in which the other person steers. I've known that go well and I've known it go horribly wrong. They can hire a 'visual' director with no narrative gift, or one of the known 'writer-killers' who don't respect the script. They can miscast key roles. In a worst-case scenario they can replace you with an untalented friend.

To be continued in Part 2

Published on July 17, 2013 03:44

July 13, 2013

The Long Road to Bedlam

At the request of crime specialist and site editor Barry Forshaw, I wrote a piece for the Interviews section of the Crime Time online website. Here's a taster:

Go to Crime Time

There are two kinds of characters that carry novel series. They're devised or they're grown, and those are quite different beasts. The devised character is like a track car, stripped of all unnecessary parts in order to run and run. The art in the creation of such a series hero is assemble just enough well-chosen characteristics to give the illusion of a character without the encumbrances of personal development. As readers, we're complicit in this. We accept Mike Hammer's life of brutal solitude without questioning from where, exactly, comes this infinite supply of Old Friends who show up needing his help.And you can read the rest here, if so inclined.

Go to Crime Time

Published on July 13, 2013 07:39

June 21, 2013

Writing a Fight Scene

I've meant to do this ever since I saw a script in which a scene contained the unhelpful direction, "They fight". And no more.

Film fights have a dramatic purpose. Gone are the days when personal violence was offered as the test and proof of a hero's moral superiority. Even in Fantasy, that's a fantasy that no longer convinces. These days even Superman takes a beating and has to resort to ingenuity in order to prevail.

So for a screenwriter to write "They fight", and then leave it to the director and stunt team to work out exactly how the conflict should play out to advance the drama, isn't enough. But nor is it helpful to choreograph every blow and angle on the page. The idea is to provide a dramatic plan, the broad strokes of staging that will release your experts to concentrate on detail.

Here are the script pages and corresponding sequence of a swordplay scene from Crusoe, performed by Philip Winchester and Georgina Rylance.I'll be the first to admit that I'm choosing this example because it went to plan and I'm happy with the way it turned out.

For me Georgina was one of the great 'finds' of the pilot; the part of Judy was cast only days before shooting and she nailed it with a strong, subtly off-centre and dangerous-feeling presence. Her showreel at georgina-rylance.com carries more Crusoe moments along with other work.

If you compare script to screen you'll see some differences - the odd line tweak or cut, Lynch's interjections to provide cutaways, bringing the daggers into the fight at a later stage - but you ought to get an idea of how the drama flows through the battle. Action in drama exists to show character, whether the crossed swords are real or verbal. Every incident is there to show us something. There's a corresponding swordfight in the series finale that shows the change in Crusoe over the season's arc; this episode's naive Englishman becomes the seasoned islander, taking Judy's lesson and turning it onto those who betrayed him.

Director Duane Clark, fight choreographer/sword master Trayan Milenev-Troy.

Crusoe on DVD

Film fights have a dramatic purpose. Gone are the days when personal violence was offered as the test and proof of a hero's moral superiority. Even in Fantasy, that's a fantasy that no longer convinces. These days even Superman takes a beating and has to resort to ingenuity in order to prevail.

So for a screenwriter to write "They fight", and then leave it to the director and stunt team to work out exactly how the conflict should play out to advance the drama, isn't enough. But nor is it helpful to choreograph every blow and angle on the page. The idea is to provide a dramatic plan, the broad strokes of staging that will release your experts to concentrate on detail.

Here are the script pages and corresponding sequence of a swordplay scene from Crusoe, performed by Philip Winchester and Georgina Rylance.I'll be the first to admit that I'm choosing this example because it went to plan and I'm happy with the way it turned out.

For me Georgina was one of the great 'finds' of the pilot; the part of Judy was cast only days before shooting and she nailed it with a strong, subtly off-centre and dangerous-feeling presence. Her showreel at georgina-rylance.com carries more Crusoe moments along with other work.

If you compare script to screen you'll see some differences - the odd line tweak or cut, Lynch's interjections to provide cutaways, bringing the daggers into the fight at a later stage - but you ought to get an idea of how the drama flows through the battle. Action in drama exists to show character, whether the crossed swords are real or verbal. Every incident is there to show us something. There's a corresponding swordfight in the series finale that shows the change in Crusoe over the season's arc; this episode's naive Englishman becomes the seasoned islander, taking Judy's lesson and turning it onto those who betrayed him.

Director Duane Clark, fight choreographer/sword master Trayan Milenev-Troy.

Crusoe on DVD

Published on June 21, 2013 08:50

June 19, 2013

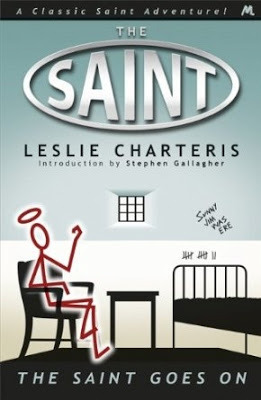

More Saintly Stuff

From Mulholland Books, with a June 20th publication date, comes this reissue of The Saint Goes On with an introduction by yours truly.

From Mulholland Books, with a June 20th publication date, comes this reissue of The Saint Goes On with an introduction by yours truly.Mulholland is an imprint of Hodder and Stoughton, publishers of the classic 'Yellow Jacket' editions. So in effect, the thirty-five reprint titles are being kept within the family.

Their number does not, at this time, include Simon Templar's first appearance in Meet the Tiger. Charteris' widow continues to honour his wishes over keeping it out of print.

Here's something of what I wrote:

"For me, the Saint of the early 1930s is as modern as the character gets; he's hard, he's principled, he seems to take nothing seriously but he can turn in a second. It's all an act. And underneath it is a very, very bright guy indeed... this is the Saint as I've always liked him best. Here, he's a man with a complete disregard for authority and a rigorous code of personal fairness. He lives high on money that he takes from thieves and the greedy rich. He appears to seek a life of luxury and entertainment, while nothing entertains him more than righting an injustice done to an innocent. But every now and again, we get a glimpse of the utter steel underneath."I had my pick of a number of titles, and I deliberately chose this one; it's The Saint before the movies, the radio serials or the TV adaptations got to him, feeding back in and reshaping the character. Before the collaborators, the ghosts, or the tie-in writers moved in.

Published on June 19, 2013 09:02

June 18, 2013

Family Values

Published on June 18, 2013 05:02

June 17, 2013

The Science Thriller

Well, I'm back from Dublin and the European Science TV and New Media Festival. As ever, the only downside of my visit to the city is that I didn't get to stay for longer. We did our panel thing in the afternoon, as part of a programme that included screenings of some of the entries in the festival's TV drama competition. I was there to represent the BBC for

Silent Witness: Legacy

but the competition's strong, including the Feynman vs NASA docudrama The Challenger, so who knows.

Well, I'm back from Dublin and the European Science TV and New Media Festival. As ever, the only downside of my visit to the city is that I didn't get to stay for longer. We did our panel thing in the afternoon, as part of a programme that included screenings of some of the entries in the festival's TV drama competition. I was there to represent the BBC for

Silent Witness: Legacy

but the competition's strong, including the Feynman vs NASA docudrama The Challenger, so who knows.The difference between science-driven dramas and drama about scientists is something that we touched on in the hour. It wasn't a debate, as such; everybody brought something different to the panel and we ranged from the coaching of actors to achieve authenticity, to the dangers of embracing bad science for popular appeal, to the wider use of media to communicate real and urgent science issues in accessible ways.

Along the way I referred to a document that I'd written for private circulation back in March 2009, when we were waiting to hear if CBS were going to pick up Eleventh Hour for a second season. Our figures were good but the omens weren't, as we'd only been given a partial order for extra episodes instead of the full 'back nine' to complete the first season.

This was a memo that I'd written at the request of the Bruckheimer people, spitballing a future direction for the show and reflecting on why our science thrillers could hold a unique place alongside the forensics and the procedurals elsewhere on the network. Having mentioned it in Dublin, I said that I'd put it online when I got home. So if you were there, here it is.

And even if you weren't, here it is anyway. It's a gathering of thoughts resulting from my experience on the ITV show, where I had little control and my commitment to scientific probity was considered unhelpful, and from the US episodes which represent some of the most satisfying work I've ever done.

The whole thing runs just over four pages and the PDF is here.

Here's an extract:

Villains and Guest CharactersThe memo was never intended for public circulation but I reckon enough time's probably passed by now.

At the beginning of my career I wrote a miniseries called Chimera, a variant on the Frankenstein story with a cold-hearted scientist as its villain. It made some waves, and through various debates and public events brought me into contact with a lot of real-world science professionals. I found that these scientists were, almost without exception, sharp, cultured, funny, and great late-night company. They were well-read, they listened to opera, they played musical instruments. Future Nobel prizewinner Paul Nurse was a motorbike nut (and was the guy who first encouraged me to dream up a real-science drama). Biologist Jack Cohen advised sf writers on alien-building. All were genuinely excited to be doing the work they did.

As much as these real scientists shaped my picture of Hood, they also shaped my attitude to science villains. The ruthless, 'playing God' stereotype, arguing that harm can be justified in the name of progress, is a cartoon. Science's villains are the same recognisably human people as those regular scientists. But they become villains through regular human flaws, not by Nazi logic. They sell out, or screw up. They can bend the truth to suit their paymasters or the policymakers, and call it 'being realistic'. They can be reckless, they can underestimate danger, they can lie to cover their mistakes, they can take desperate measures to cover their lies. But science's villains are characterised by their human failings, not by single-minded immoral intent.

And often they won't even be scientists, but people who co-opt science to their own purposes. CEOs, charlatans, toxic waste dumpers, politicians, lobbyists, thieves, counterfeiters, scammers, conspiracy theorists, drug lords, mobsters. People like the real-life international hustler and would-be breakthrough human cloner who provided the model for the bad guy in my very first story.

You may find it a useful snapshot of a discussion in the show-making process. Just bear in mind that we didn't get the pickup!

Published on June 17, 2013 07:28

June 14, 2013

Science and Drama in Dublin

If you're in Dublin tomorrow, you can come and see me yak at this free Science Gallery event. It's part of the 2013 European Science TV and New Media Festival, with a keynote speech followed by a panel discussion.

It's the first one of these I've done in a while, and I'm looking forward to it. Some time ago I was involved in a discussion organised by The Wellcome Trust; there's a report on that event here, and here you can read the text of my presentation.

My views may have changed a little since then, I suspect. But I won't find out for sure until I hear what I have to say.

14.00 - KEYNOTE TALK AND PANEL-LED DISCUSSION SESSIONI'm there because my Silent Witness two-parter Legacy is one of the BBC's shortlisted entries in the Drama category of the festival competition, along with the Feynman vs NASA teleplay The Challenger. I've no idea where the discussion will lead but perhaps we'll get to talk a little about whether there's a distinction between science-driven drama, and dramas about scientists.

Science, Medicine and Media

Keynote Talk: Dr David Kirby, Senior Lecturer in Science Communication, University of Manchester, UK

The Representation of Scientists in TV and Film Panel-led Discussion

Chair: Diarmaid Mac Mathuna, Head of Client Services, Agtel, Dublin

Speakers include: Kathriona Devereux, Scientist and TV Presenter Dr Mark Little, Professor of Nephrology, Trinity Health Kidney Centre, Trinity College Dublin / Tallaght and Beaumont Hospitals, Stephen Gallagher, TV Writer of science based drama.

It's the first one of these I've done in a while, and I'm looking forward to it. Some time ago I was involved in a discussion organised by The Wellcome Trust; there's a report on that event here, and here you can read the text of my presentation.

My views may have changed a little since then, I suspect. But I won't find out for sure until I hear what I have to say.

Published on June 14, 2013 05:44

June 10, 2013

Brown Paper Packages, Tied Up with String

There's a long-established and old-fashioned bookshop in Southport, Lancashire, called Broadhurst's - new books downstairs, old books above, and they wrap your purchase in brown paper and string before you leave. The really high-value stuff is in a room that resembles Sherlock Holmes' study, with a velvet rope across the doorway, while on the same landing is a room filled with more modestly-priced first editions.

I was there a couple of weeks ago, and though I wasn't specifically searching for it, in the latter room my eye was caught by a copy of the Ward Lock version of Meet the Tiger. This was the novel in which Leslie Charteris introduced Simon Templar, alias The Saint, to the world. Charteris was in his 20s when he wrote it, and later in his career he'd declare himself so dissatisfied with the book that he withdrew it from sale. It was a second (1929) edition rather than a first, but a rather nice one. I read the opening page; yep, regardless of his later disclaimers, the Charteris voice was there and the character read as recognisable and fully-formed.

It wasn't exactly cheap, but it wasn't Vanderbilt money either. I like books that have aged gracefully, and I'd rather have something affordable and a bit shabby than mint and untouchable. After I came away, it played on my mind so I did some internet research and established that a) the second-edition price was probably a fair one, and b) I could put aside any thoughts of a first edition. So I went back this Saturday and visited again, read a couple more pages, left the shop and walked around a bit to prolong the moment, then caved in and bought the book. For the wrapping they have a purpose-made 1920s table with the brown paper being pulled down from a roller and the string from a ball.

So now here's my problem. I've brought it home and I can't bring myself to undo the parcel. A brown paper package, that's tied up with string. It's sitting on the shelf in the open, an ornament in itself.

But I will open it. Real soon now.

I was there a couple of weeks ago, and though I wasn't specifically searching for it, in the latter room my eye was caught by a copy of the Ward Lock version of Meet the Tiger. This was the novel in which Leslie Charteris introduced Simon Templar, alias The Saint, to the world. Charteris was in his 20s when he wrote it, and later in his career he'd declare himself so dissatisfied with the book that he withdrew it from sale. It was a second (1929) edition rather than a first, but a rather nice one. I read the opening page; yep, regardless of his later disclaimers, the Charteris voice was there and the character read as recognisable and fully-formed.

It wasn't exactly cheap, but it wasn't Vanderbilt money either. I like books that have aged gracefully, and I'd rather have something affordable and a bit shabby than mint and untouchable. After I came away, it played on my mind so I did some internet research and established that a) the second-edition price was probably a fair one, and b) I could put aside any thoughts of a first edition. So I went back this Saturday and visited again, read a couple more pages, left the shop and walked around a bit to prolong the moment, then caved in and bought the book. For the wrapping they have a purpose-made 1920s table with the brown paper being pulled down from a roller and the string from a ball.

So now here's my problem. I've brought it home and I can't bring myself to undo the parcel. A brown paper package, that's tied up with string. It's sitting on the shelf in the open, an ornament in itself.

But I will open it. Real soon now.

Published on June 10, 2013 12:05

June 5, 2013

Hammer Chillers - The Box

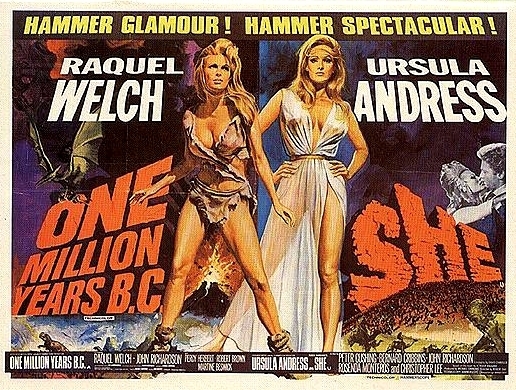

I recently guested on a late-night radio music-and-chat show where the topic of conversation was "My Mis-Spent Youth". To be honest, I don't think my youth was particularly mis-spent. Comics, B-movies, telefantasy and cheap paperbacks pretty much gave me a career. But you have to get into the spirit of the thing.

I recently guested on a late-night radio music-and-chat show where the topic of conversation was "My Mis-Spent Youth". To be honest, I don't think my youth was particularly mis-spent. Comics, B-movies, telefantasy and cheap paperbacks pretty much gave me a career. But you have to get into the spirit of the thing.So I talked about my happy hours at the Prince's Cinema in Monton, just outside Manchester. The subject was fresh in my mind because I'd recently given this interview to Simon Barnard of Bafflegab, the production company entrusted with the making of Hammer Films' new series of audio Chillers.

It was at the Prince's (Prince, singular) that I first encountered Hammer films in all their gory big-screen glory, in the form of the Sunday double-bill. Barely remembered now, the Sunday double feature was a programming mainstay of the UK's local cinemas. With Hammer you always got value, but often they were the kind of films where the posters promised much, and the films delivered... well, perhaps not quite so much. You'd find anything from William Castle films to early Cronenberg; it was here that I saw Herk Harvey's Carnival of Souls, a no-budget gem whose poetry shone through the most basic of craft, and which I've written about here.

In an earlier post I wrote:

In an earlier post I wrote: The Prince's was only a little local cinema, not one of the first-run houses. It was a classic 'Smallest Show on Earth' place, managed by a husband-and-wife team whose quiet dedication to their calling I'm only now able to appreciate. They ran a kids' Saturday matinee that was like a zoo during an earthquake. He wore a suit and dickie-bow and ran the front-of-house; she had one of those '60s piled-high hairdos and sold the tickets.I don't think I ever knew them by name, but the internet serves them up as Jim and Joan Shepherd. It was Joan who, when I was hit on the head by a flying frozen Jubbly (Google it) thrown from the back of the stalls, dried my tears, cleaned me up, and sent me home to change before readmitting me just in time for the cartoons and serial.

And it was Joan who turned a blind eye when I started showing up for the Sunday Hammer doubles when barely into my teens. The films were X-rated but after all those matinee Saturdays she recognised my devotion, I'm sure.

And now the world comes full circle. I've had various Hammer connections over the years, though for decades it was more of an undead company than a living one. Right at the beginning of my career I had a number of pitch meetings with John Peacock, scripter of To The Devil a Daughter and sometime story editor on Hammer House of Mystery and Suspense, at that time the point man for a revival by the company's new owners. They didn't buy anything from me but I'm consoled by the fact that they didn't buy anything from anyone else, either. Whenever the company changed hands, there was always the announcement of a new lease of life for a great British brand, the promise of a slate of new high-class horror. But as one insider explained to me, the reality was that the back catalogue was the real prize, a modest but reliable cash cow, whereas new production offered nothing but risk.

In the meantime I was getting to meet many of my Hammer heroes at the Manchester Festival of Fantastic Films. My daughter would scurry about the place collecting autographs; years later, as PA to Hammer CEO Simon Oakes, she'd be the only company employee able to name-drop the likes of Val Guest, Jimmy Sangster, or Eddie Powell.

(A job she landed without any help from me, I ought to add. None of your "James Caan" special privileges here. Even if she'd cared to trade on it, my small faux pas in an earlier pitch meeting would have made my name a dubious asset at best.)

But now here we are; with Friday's release of the Hammer Chillers I get to be a part of it all at last. The Chillers are half-hour audio dramas, available as downloads or as a CD digipack, to be released on a weekly schedule with scripts from Mark Morris, Paul Magrs, Christopher Fowler, Robin Ince, and Stephen Volk. A killer lineup by anyone's standards.

My story, The Box, is up first. I've listened to an advance copy and I'm really happy with the way it's turned out. It's something of a return to my roots and the first audio piece I've written, I think, since my episodes for Radio 4's Man in Black series.

An early review from Starburst reads:

"...the truth behind The Box was one that will stay with me for a while... As an audio production this is first rate; from the first bar of the opening music to the final bar of the close the sound is full, rich and deserving of being heard on decent headphones or speakers. All the ingredients come togetherThere’s a steadily rising air of threat throughout the story... A neat tale whose last line will haunt you long after it’s finished.The Box launches the series on Friday, June 7th.

Click here for everything you need to know about the Hammer Chillers.

www.hammerchillers.com

Published on June 05, 2013 08:57