Stephen Gallagher's Blog, page 28

December 15, 2012

From the Archive

The Stephen Laws archive, that is, or more correctly it's lifted from his Facebook page. No, it's not horror fiction's very own Boy Band. That's the late and much-loved Charles L Grant, me with Paul McCartney's hair, Laws, and Bigdog himself Joe R Lansdale at the BFS Awards.

Laws is a notorious pickpocket, which is why Charlie and I are guarding our change. Laws is venting his frustration by goosing Joe.

And what can I say? It was the 80s. We all tucked our shirts in our pants back then.

Published on December 15, 2012 02:30

December 12, 2012

Dead Static

If you're in London, from now until Saturday night you can catch the second run of the science fiction comedy Dead Static at the Hen and Chickens theatre in Islington.

Tickets are nine quid. I believe there are still comps available for bona fide reviewers (ie, if you can prove you are one, and not that you just suddenly decided to be one to snag a freebie).

The List describes it as "Steve Jordan's science-fiction comedy about an over-confident smuggler and an insufferably upbeat conman trapped in a shuttle on a collision course with an asteroid belt." The play runs an hour and it's over a pub, so what's not to like? Have a drink, wander up to see the play, come back down and have another.

I saw it in its first run at the Camden Fringe. I had a great time. The show's associate producer is Little Miss Brooligan, aka Ellen Gallagher. Collar her after the show and ask her what an associate producer does and if you find out, tell me.

Logo design is by Paul Drummond, who designed this blog and the website of which it's part.

It's a tiny, tiny world.

Published on December 12, 2012 10:34

December 11, 2012

Shedding Light on the Valley

Writing about Greg Hoblit's supernatural chase thriller The Fallen for her Cats on Film blog, Anne Billson got in touch to clarify a point.

Apparently some of the Amazon reviewers of my 1987 novel Valley of Lights contend that it owes something to Jack Sholder's movie The Hidden. In Valley of Lights, a Phoenix police sergeant is targeted by an ageless, amoral body-hopping entity that has been living on the fringes of society for so long that it can't even remember its own origin. It's not a great life; it's an eternity of lying low, until threatened by discovery.

Apparently some of the Amazon reviewers of my 1987 novel Valley of Lights contend that it owes something to Jack Sholder's movie The Hidden. In Valley of Lights, a Phoenix police sergeant is targeted by an ageless, amoral body-hopping entity that has been living on the fringes of society for so long that it can't even remember its own origin. It's not a great life; it's an eternity of lying low, until threatened by discovery.

I wrote the book in '85 and in July '86 it was optioned by AWGO (Anciano Wyn-Griffith Orme), a newly-formed UK company with Hollywood feature ambitions. In October '86 director

New Line finally said no. The guys were talking to other backers as well, but when New Line released The Hidden in October '87 our movie was dead. We didn't know it right away, but it was.

Did The Hidden rip us off? It's hardly likely. But does Valley owe anything to The Hidden? Not a thing. It was out first.

Anne's blog post is here. I like The Hidden. It's a fun movie. I've never seen Fallen.

Apparently some of the Amazon reviewers of my 1987 novel Valley of Lights contend that it owes something to Jack Sholder's movie The Hidden. In Valley of Lights, a Phoenix police sergeant is targeted by an ageless, amoral body-hopping entity that has been living on the fringes of society for so long that it can't even remember its own origin. It's not a great life; it's an eternity of lying low, until threatened by discovery.

Apparently some of the Amazon reviewers of my 1987 novel Valley of Lights contend that it owes something to Jack Sholder's movie The Hidden. In Valley of Lights, a Phoenix police sergeant is targeted by an ageless, amoral body-hopping entity that has been living on the fringes of society for so long that it can't even remember its own origin. It's not a great life; it's an eternity of lying low, until threatened by discovery.I wrote the book in '85 and in July '86 it was optioned by AWGO (Anciano Wyn-Griffith Orme), a newly-formed UK company with Hollywood feature ambitions. In October '86 director

New Line finally said no. The guys were talking to other backers as well, but when New Line released The Hidden in October '87 our movie was dead. We didn't know it right away, but it was.

Did The Hidden rip us off? It's hardly likely. But does Valley owe anything to The Hidden? Not a thing. It was out first.

Anne's blog post is here. I like The Hidden. It's a fun movie. I've never seen Fallen.

Published on December 11, 2012 03:04

December 6, 2012

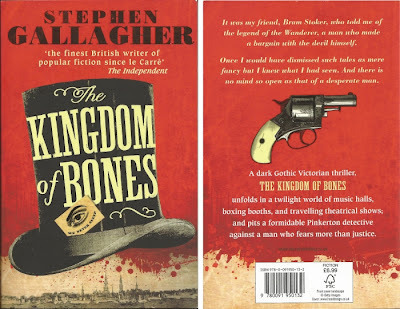

It's Publication Day

The British paperback edition of The Kingdom of Bones, the novel that introduces The Bedlam Detective's Sebastian Becker, is published today by Ebury Press.

Marilyn Stasio in The New York Times wrote:

Marilyn Stasio in The New York Times wrote:

THE KINGDOM OF BONES... shows the occult mystery in its best light. Vividly set in England and America during the booming industrial era of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, this stylish thriller conjures a perfect demon to symbolize the age and its appetites, an entity that inhabits characters eager to barter their souls for fame and fortune. When met, this demon is residing in Edmund Whitlock, an actor whose life gives us entry into the colorful world of traveling theatricals. When Whitlock passes on his curse to the company soubrette, the troupe manager follows her to America, intent on rescuing her, and runs afoul of the law. Although Gallagher delivers horror with a grand melodramatic flourish, his storytelling skills are more subtly displayed in scenes of the provincial theaters, gentlemen’s sporting clubs and amusement parks where a now-vanished society once took its rough pleasures.And this from crime titan Ed Gorman:

"I read Stephen Gallagher for two reasons. First because he's one of the most entertaining writers I've ever read. And second because I can't read a short story of his let alone a novel without picking up a few pointers about writing. He's an elegant stylist, a shrewd psychologist and a powerful storyteller with enormous range and depth.

"I finished his latest novel The Kingdom of Bones and I was honestly stunned by what he'd done. The sweep, the majesty, the grit, the grue, the great grief (and the underpinning of gallows humor from time to time). This is not only the finest novel I've read this year but the finest novel I've read in the past two or three years."

Published on December 06, 2012 07:41

November 27, 2012

Best of 2012

Woo-hoo. Kirkus has named The Bedlam Detective as one of the best mysteries of the year.

I believe a small glass of something may be called for.

The 'Read full review' link in the image won't work, but this one will.

While waiting for the softcover edition to be published in February, why not prepare the ground with Sebastian Becker's first outing in The Kingdom of Bones, in UK paperback from Ebury Press on December 6th?

No, you're quite right, I have no shame at all.

I believe a small glass of something may be called for.

The 'Read full review' link in the image won't work, but this one will.

While waiting for the softcover edition to be published in February, why not prepare the ground with Sebastian Becker's first outing in The Kingdom of Bones, in UK paperback from Ebury Press on December 6th?

No, you're quite right, I have no shame at all.

Published on November 27, 2012 09:49

November 24, 2012

Sherlocks

Like many people who'd embraced Sherlock I was prepared to dislike CBS's Elementary just on principle, but I don't. The Brooligan household watched the pilot and we decided, after some discussion, not to bother with the series; based on that viewing it felt less than fresh, and the mystery element was weak. Subsequent episodes lurked around on the PVR until I came home late one night with a yen for something entertaining but not too challenging, to unwind with before sleeping. Elementary and I had found each other's level.

Here's the thing about American TV shows. Where British series can start out strongly and lose oomph as their overloaded creators run out of steam - witness the quality arc of Jonathan Creek, a Sherlock of the '90s - US series tend to find their feet as the team comes together. Much like the British Sherlock, the show's strength arises from a lead role played as a character part with all the stops out; though unlike the British version, Lucy Liu's Watson seems to be fading into the background with very little to do.

Comparisons are inevitable and deny it though the makers might, it's pretty obvious that Elementary's driven, dysfunctional take on a modern Sherlock owes more than a little to its British antecedent. Only a career-best performance from Jonny Lee Miller makes you rise above the thought that it's Benedict Cumberbatch's character with the serial numbers filed off. In fact you could pretty much swap the leads of the two versions, as Miller and Cumberbatch did nightly in the National Theatre's Frankenstein.

But the point was well made by a fan of both shows. With Sherlock, it's three a year. Fewer, if you average it out. Despite shedding a couple of million viewers after the pilot, Elementary quickly got its 'back nine' pickup, extending the series order from thirteen episodes to a full season of twenty-two. CBS has since ordered a further two episodes to extend the season to twenty-four. It's a mass product for a mass market, and a successful one of its kind. It'll do until Sherlock comes around again.

I'd have to agree. If we disdain something just because we think it's derivative, where will that leave us? Smug and pure, but with no popular culture and nothing to watch, that's where. You can have a preference, but it's still OK to see both. Life may be short, but it's not that short.

When I looked up Elementary's numbers, I was surprised to see how they compared to Eleventh Hour's in the same Thursday 10pm CBS slot. We got cancellation with a season's average of 12.15 million; Elementary's weekly average so far is 11.12 and they get a champagne party (that figure may well be lower by the season's end, unless the lost 2 million from the pilot come back).

Here's the difference; Eleventh Hour was made for CBS by the Warner Bros studio. Elementary is made for CBS by CBS Studios. When the network pays its own studio for the show, the money stays in the family.

It's always about the numbers, but not necessarily about the numbers you think.

Here's the thing about American TV shows. Where British series can start out strongly and lose oomph as their overloaded creators run out of steam - witness the quality arc of Jonathan Creek, a Sherlock of the '90s - US series tend to find their feet as the team comes together. Much like the British Sherlock, the show's strength arises from a lead role played as a character part with all the stops out; though unlike the British version, Lucy Liu's Watson seems to be fading into the background with very little to do.

Comparisons are inevitable and deny it though the makers might, it's pretty obvious that Elementary's driven, dysfunctional take on a modern Sherlock owes more than a little to its British antecedent. Only a career-best performance from Jonny Lee Miller makes you rise above the thought that it's Benedict Cumberbatch's character with the serial numbers filed off. In fact you could pretty much swap the leads of the two versions, as Miller and Cumberbatch did nightly in the National Theatre's Frankenstein.

But the point was well made by a fan of both shows. With Sherlock, it's three a year. Fewer, if you average it out. Despite shedding a couple of million viewers after the pilot, Elementary quickly got its 'back nine' pickup, extending the series order from thirteen episodes to a full season of twenty-two. CBS has since ordered a further two episodes to extend the season to twenty-four. It's a mass product for a mass market, and a successful one of its kind. It'll do until Sherlock comes around again.

I'd have to agree. If we disdain something just because we think it's derivative, where will that leave us? Smug and pure, but with no popular culture and nothing to watch, that's where. You can have a preference, but it's still OK to see both. Life may be short, but it's not that short.

When I looked up Elementary's numbers, I was surprised to see how they compared to Eleventh Hour's in the same Thursday 10pm CBS slot. We got cancellation with a season's average of 12.15 million; Elementary's weekly average so far is 11.12 and they get a champagne party (that figure may well be lower by the season's end, unless the lost 2 million from the pilot come back).

Here's the difference; Eleventh Hour was made for CBS by the Warner Bros studio. Elementary is made for CBS by CBS Studios. When the network pays its own studio for the show, the money stays in the family.

It's always about the numbers, but not necessarily about the numbers you think.

Published on November 24, 2012 06:07

November 14, 2012

The Next Big Thing

Guy Adams, the Torchwood/Sherlock/Hammer novelist and Angry Robot-published author, has tagged me for this. I didn't even realise I'd annoyed him.

It's called a Blog Hop. Here's how it works, he said to me. You answer ten questions on the next big thing that you're working on, then tag five other writers to do the same. Which sounds a little bit like that "grains of rice on a chessboard" thing... within a matter of weeks it'll all reach a crisis, and we'll be fighting each other over the last few taggable authors with rock axes and knives made from dinosaur bones.

What is the working title of your next book?

Well, the next one to appear will be the UK edition of The Kingdom of Bones but the one I'm working on is the third novel featuring Sebastian Becker, which I'm calling The Authentic William James.

Where did the idea come from?

I got my villain first. Which makes a kind of sense when you think about it. In this kind of story, it's someone's misdeed that sets everything in motion. If that's credible and there's genuine human motivation behind it, your foundation's going to be strong.

What genre best defines your book?

It's a big dark historical crime thriller, set in 1913.

What actors would you choose to play the part of your characters in a movie?

Seriously, or in a fantasy-football-league sense? I'm not sure I can offer a thought for either. I'm not being evasive, but the career strategy issues and market politics of casting fascinate me. You don't often get the person you want. You get the most bankable person who needs your movie. If you're lucky, they'll connect with your vision to some extent; if they don't, you pretty much have to grin and suck it up. Having seen how it works, I find I can't do the speculation thing any more.

What is the one-sentence synopsis of your book?

A burning theatre, a kidnapped teen, and Sebastian Becker in pursuit of the morphine junkie cowboy that Buffalo Bill left behind.

Will your book be self-published or represented by an agency?

I'm represented. For the novels it's Howard Morhaim in New York, Abner Stein in London. For screen work I'm with UTA and The Agency. Please don't ask for an introduction. It doesn't work like that.

How long did it take you to write the first draft?

Ask me that when it's done. My first drafts are preceded by a lot of research and preparation. When I'm ready to sit down and pull it all together, it takes about twelve weeks.

What other books would you compare this story to within your genre?

I'm sui generis, apparently. Which I suspect may be a euphemism for "difficult to place".

Who or what inspired you to write this book?

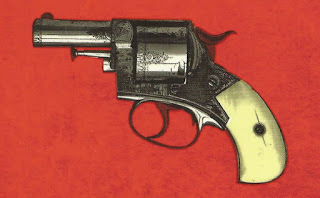

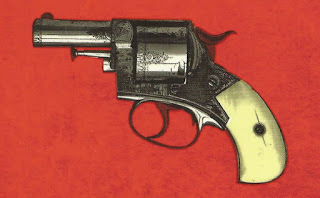

All the Becker books include an element of Old Showbusiness. In The Kingdom of Bones it was a touring Victorian theatrical troupe, in The Bedlam Detective there's a crucial element tied in with early British cinema. For decades after William Cody's final UK tour, a number of British fairground families made their living with home-grown Western sideshows. They lived the life and learned the skills of shooting, roping, knife-throwing... and in the original show, one of Cody's performers did suffer a horrific riding accident and stayed on in Europe to recover. My what-if question - what if one of the British families took him in to lend their act some authenticity? Only to find that they'd opened up their family to an embittered monster? Everything flowed from there.

What else about the book might pique the reader's interest?

It's the third novel to feature Sebastian Becker, Special Investigator to the Lord Chancellor's Visitor in Lunacy. He makes his first appearance in The Kingdom of Bones, published in the UK by Ebury Press in December. The Bedlam Detective follows in February.

~

These "Next Big Thing" blogposts are planned to appear every Wednesday. For next week, I'm tagging fellow Suspensers Joel Goldman and Harry Shannon, Cumbria-based crime writer Zoë Sharp, adopted son of Chicago Tim Lees, and Prince of Brit Horror Stephen Laws.

It's called a Blog Hop. Here's how it works, he said to me. You answer ten questions on the next big thing that you're working on, then tag five other writers to do the same. Which sounds a little bit like that "grains of rice on a chessboard" thing... within a matter of weeks it'll all reach a crisis, and we'll be fighting each other over the last few taggable authors with rock axes and knives made from dinosaur bones.

What is the working title of your next book?

Well, the next one to appear will be the UK edition of The Kingdom of Bones but the one I'm working on is the third novel featuring Sebastian Becker, which I'm calling The Authentic William James.

Where did the idea come from?

I got my villain first. Which makes a kind of sense when you think about it. In this kind of story, it's someone's misdeed that sets everything in motion. If that's credible and there's genuine human motivation behind it, your foundation's going to be strong.

What genre best defines your book?

It's a big dark historical crime thriller, set in 1913.

What actors would you choose to play the part of your characters in a movie?

Seriously, or in a fantasy-football-league sense? I'm not sure I can offer a thought for either. I'm not being evasive, but the career strategy issues and market politics of casting fascinate me. You don't often get the person you want. You get the most bankable person who needs your movie. If you're lucky, they'll connect with your vision to some extent; if they don't, you pretty much have to grin and suck it up. Having seen how it works, I find I can't do the speculation thing any more.

What is the one-sentence synopsis of your book?

A burning theatre, a kidnapped teen, and Sebastian Becker in pursuit of the morphine junkie cowboy that Buffalo Bill left behind.

Will your book be self-published or represented by an agency?

I'm represented. For the novels it's Howard Morhaim in New York, Abner Stein in London. For screen work I'm with UTA and The Agency. Please don't ask for an introduction. It doesn't work like that.

How long did it take you to write the first draft?

Ask me that when it's done. My first drafts are preceded by a lot of research and preparation. When I'm ready to sit down and pull it all together, it takes about twelve weeks.

What other books would you compare this story to within your genre?

I'm sui generis, apparently. Which I suspect may be a euphemism for "difficult to place".

Who or what inspired you to write this book?

All the Becker books include an element of Old Showbusiness. In The Kingdom of Bones it was a touring Victorian theatrical troupe, in The Bedlam Detective there's a crucial element tied in with early British cinema. For decades after William Cody's final UK tour, a number of British fairground families made their living with home-grown Western sideshows. They lived the life and learned the skills of shooting, roping, knife-throwing... and in the original show, one of Cody's performers did suffer a horrific riding accident and stayed on in Europe to recover. My what-if question - what if one of the British families took him in to lend their act some authenticity? Only to find that they'd opened up their family to an embittered monster? Everything flowed from there.

What else about the book might pique the reader's interest?

It's the third novel to feature Sebastian Becker, Special Investigator to the Lord Chancellor's Visitor in Lunacy. He makes his first appearance in The Kingdom of Bones, published in the UK by Ebury Press in December. The Bedlam Detective follows in February.

~

These "Next Big Thing" blogposts are planned to appear every Wednesday. For next week, I'm tagging fellow Suspensers Joel Goldman and Harry Shannon, Cumbria-based crime writer Zoë Sharp, adopted son of Chicago Tim Lees, and Prince of Brit Horror Stephen Laws.

Kansas City-born Joel Goldman writes, "I became a ten-year overnight success with the publication of my first book, Motion To Kill, in 2002, introducing trial lawyer Lou Mason." Joel retired from his law practice in 2006 to write full-time, and has never looked back. His series include the Jack Davis thrillers and the soon-to-be-launched stories featuring Alex Stone, public defender.

Harry Shannon is a former actor, musician, Carolco VP, film music supervisor, now primarily a novelist with a sideline in short fiction. He's the author of the much-praised Mick Callahan novels. Media psychologist Callahan is "a failed Navy Seal, a recovering alcoholic and a loyal friend. He's also a man with a hot temper and a talent for getting himself into trouble."

Zoë Sharp is the creator of a series of novels featuring Charlotte 'Charlie' Fox, an action heroine who finds close protection work the perfect career for an ex-Special Forces trainee who has never been quite in step with life outside the army that rejected her. Zoë's hobbies are sailing, fast cars (and faster motorbikes), target shooting, travel, films, music, and reading just about anything she can get her hands on.

Tim Lees is a British author living in Chicago, responsible for numerous short stories and the pitch-perfect Frankenstein's Prescription, described as "a brilliant novel, one which takes the old stereotype and fills it with vibrant new life. The story is gripping, with each and every element of the plot fitting into place perfectly." (Peter Tennant, Black Static). It's available from Tartarus Press.

Newcastle-based Stephen Laws kicked off his career with Ghost Train. He's the author of 11 novels, numerous short stories (collected in The Midnight Man), as well as a columnist, reviewer, film-festival interviewer, pianist and recipient of numerous awards. He survived an early attempt by his publisher to promote him as "A Herbert for the 90s". Read about his heroic encounter with a Spanish zombie master here.

Published on November 14, 2012 03:10

November 4, 2012

The Killing 3

"I like working with the actors and with the producer, it's normal for me, but outside Danish Broadcasting, maybe it's old school – the director is king, the writer's more the guy you get some scripts from and then you see him again at the premiere. If they're just looking for a writer, then maybe I'm not the one."

Good interview with THE KILLING creator/showrunner Soren Sveistrup in The Independent - click here to read it in full.

Published on November 04, 2012 09:30

October 20, 2012

Nightmares and Angels

Just after the Berlin wall came down, I threw a bag into the back of the Volvo and drove down to the Hamburg ferry. Not quite as spontaneously as that, of course. I had a plan. I'd lined up meetings with Hamburg's Sex Crimes division and detectives in the Criminal Investigation department of the Dussseldorf police. I had places to look at, questions to ask, and a date with the Senior Pathologist in the morgue at Heinrich Heine University.

But in the most ambitious part of the trip, I headed East. Right across Germany, through the border, and into territory that had, only months before - weeks, even - been sealed off, self-contained, an enigma to the West.

For someone raised on spy fiction, this was no small deal. In Cold War mythology, East Germany was enemy territory. In reality the border was a zone of tension, and people died trying to cross it.

What I found was empty checkpoints, broken barriers, watchtowers with their windows stoned-in... there were concrete blocks that had been placed to prevent any vehicle from making a dash through, forcing the car into a zigzag path that no longer served any purpose. This once-fearsome locale now felt like a corner of an abandoned airfield, already becoming overgrown.

And what I found on the other side resembled the Britain of my earliest memories. It was as if time had stopped in the 1950s, which I suppose it pretty much had. Fields, farms, and villages were untouched. Where there was industry, it was like a concentrated dump of poison in an otherwise bucolic landscape. My most powerful visual memory is of the bright yellow hillsides of oilseed rape, unnatural in their intensity, a sight that always takes me back not only to the place, but to that precise time of the year.

I don't know what they must have made of the Volvo. At least half of the cars I saw on the road were Trabants, those tiny two-stroke polluters with bodyshells made of cotton waste and resin. The Volvo was a red 480 ES, one of those sports coupés with which they sometimes surprise the market, pictured here as it appeared in Bryan Talbot's The Tale of One Bad Rat. Driving around in it made me feel like Commander Straker in UFO.

I covered my checklist of sights and places, I gathered atmosphere and detail. It was all for a novel called Nightmare, with Angel.

I stayed in some odd places; one night in an inn where they kindly but apologetically gave me a tiny stockroom behind the bar with a bed in it, another in a workers' subsidised country vacation home, vast as the Overlook Hotel and just as empty. Along the way I found everything that I needed for the novel, and much that I'd never imagined. It didn't all find its way in, but it all made a difference. That's research for you.

I look back at some of the stuff I've done in the course of my career and wonder how I had the nerve. I had no one to guide me, I'd made no advance reservations. I didn't even speak any German. I did have a map and a phrasebook. I wasn't a complete idiot.

Here's how I began my pitch for the novel:

The novel did rather well for me, and one way or another it'll be available again soon. Don't ask me which way, because that isn't settled yet.

A couple of years later I traded in the Volvo for a sensible family wagon. Lots of legroom for the rear seats, plenty of luggage space, and room for the dogs.

This year, I traded back.

But in the most ambitious part of the trip, I headed East. Right across Germany, through the border, and into territory that had, only months before - weeks, even - been sealed off, self-contained, an enigma to the West.

For someone raised on spy fiction, this was no small deal. In Cold War mythology, East Germany was enemy territory. In reality the border was a zone of tension, and people died trying to cross it.

What I found was empty checkpoints, broken barriers, watchtowers with their windows stoned-in... there were concrete blocks that had been placed to prevent any vehicle from making a dash through, forcing the car into a zigzag path that no longer served any purpose. This once-fearsome locale now felt like a corner of an abandoned airfield, already becoming overgrown.

And what I found on the other side resembled the Britain of my earliest memories. It was as if time had stopped in the 1950s, which I suppose it pretty much had. Fields, farms, and villages were untouched. Where there was industry, it was like a concentrated dump of poison in an otherwise bucolic landscape. My most powerful visual memory is of the bright yellow hillsides of oilseed rape, unnatural in their intensity, a sight that always takes me back not only to the place, but to that precise time of the year.

I don't know what they must have made of the Volvo. At least half of the cars I saw on the road were Trabants, those tiny two-stroke polluters with bodyshells made of cotton waste and resin. The Volvo was a red 480 ES, one of those sports coupés with which they sometimes surprise the market, pictured here as it appeared in Bryan Talbot's The Tale of One Bad Rat. Driving around in it made me feel like Commander Straker in UFO.

I covered my checklist of sights and places, I gathered atmosphere and detail. It was all for a novel called Nightmare, with Angel.

I stayed in some odd places; one night in an inn where they kindly but apologetically gave me a tiny stockroom behind the bar with a bed in it, another in a workers' subsidised country vacation home, vast as the Overlook Hotel and just as empty. Along the way I found everything that I needed for the novel, and much that I'd never imagined. It didn't all find its way in, but it all made a difference. That's research for you.

I look back at some of the stuff I've done in the course of my career and wonder how I had the nerve. I had no one to guide me, I'd made no advance reservations. I didn't even speak any German. I did have a map and a phrasebook. I wasn't a complete idiot.

Here's how I began my pitch for the novel:

Imagine this.So the story that swept all the way to the East began closer to home, on a part of the British seacoast that I knew quite well. Sunderland Point is one of those places that can only be reached by a causeway at low tide. Strange, desolate and charming, it's one of the most atmospheric places I know. At the time I was experimenting with one of those panoramic cameras that took a picture like a school photo. It was a format that somehow suited the landscape.

You've got a nine year old girl who lives alone with her father in a big old house by the sea. Every day she looks more like her mother, and her mother was a tramp. Because of this her father all but ignores her, the woman who keeps house in the daytime also keeps her distance, and the child has to face a solitary life with only a scavenged photograph of her mother for comfort and a wishful image of what it might be like to be loved again. Her father isn't a hard man; but he's a mess, he's losing his grip, and he doesn't seem to see how he's losing his daughter as well. When he notices her, he's impossibly strict. But most of the time he's absorbed by his own bitterness, and he hardly notices her at all. Her days are long, and as bleak and empty as the coastal landscape around the house where she roams. With her father seemingly lost to her, she needs a father‑figure to take his place; and on the day that she falls into one of the big sea‑drains by the town dump and has to be rescued by a stranger, she thinks that she's found one.

His name is Ryan. He lives in a rented shack by the railway line and makes a living however he can; odd jobs, casual work, fixing up abandoned appliances, cleaning out aluminium cans and bagging them for scrap. He gets her out, he takes her home and, without waiting for thanks, he walks away.

But it isn't going to be so easy for him.

The novel did rather well for me, and one way or another it'll be available again soon. Don't ask me which way, because that isn't settled yet.

A couple of years later I traded in the Volvo for a sensible family wagon. Lots of legroom for the rear seats, plenty of luggage space, and room for the dogs.

This year, I traded back.

Published on October 20, 2012 10:26

October 15, 2012

Creating the Audio Drama

The first professional work I ever did was in radio drama, and I did quite a lot of it. Long form stuff, six-part serials and 90-minute plays. It’s a medium that provides a grounding that’s equally valid for both novel and screenplay writing. You learn to structure, and to structure over distance. You learn to balance scenes; you learn how to do speakable dialogue that carries story while still sounding like things that real people might say. And, strange though it may sound, you learn the absolute value of the image as a way to deliver meaning. You don’t have visuals in radio, so you’re forever seeking ways to put them in the audience’s mind, and you’ve an awareness of the need for them to count for something. You can turn on your TV any night of the week and see writing that doesn’t attempt any of that. People in rooms telling each other the plot. One up from that is the whole school of thought that believes the only ‘proper’ drama is two people arguing bitterly about their relationship.

It's only looking back that I realise how fortuitous my career timing was. With just one spec Saturday Night Theatre script it was like I stepped into radio's National Theatre. My very first producer (on Radio 4's The Humane Solution) was the legendary John Tydeman, who'd pretty much launched the careers of Joe Orton and Tom Stoppard. He was head of drama and led a very small team of highly experienced producers. Martin Jenkins did my next (An Alternative to Suicide) and I think with one exception he produced everything I wrote for BBC radio thereafter. We got on really well. While I was still working for Granada he came up to Manchester and I took him to see the outdoor set of Coronation Street, of which he was a fan. But he obviously enjoyed the fact that my stuff was anything but social realism, and that it gave him opportunities to push the medium in all kinds of unusual ways. On Alternative, which was a science fiction piece, I can remember the studio managers wiring up every piece of weird and extreme equipment in the building, tying up every channel and turntable. When I had to leave for my train they were still bringing in more.

On the half-hour Man in Blacks, I'd write the framing narration and it was understood that Martin would rewrite it for his needs. Those episodes now seem to be in constant repertory on Radio 4 Extra. Audio horror has an advantage, in that we're unsettled by incomplete information. Who's outside? What's making that noise? The moment you switch the lights on to see, that entire little universe of uncertainty collapses into something quantified. But with audio horror there's always something legitimately withheld.

I suppose if there's a weakness, it's that a lot of people imagine that an explicit visual trumps a quiet suggestion. If hearing someone scratching at your door is scary, the logic goes, then surely being confronted by them must be scarier still. I never really had to modify my writing because there was a very short note-giving chain and the people I was working with were all trained and experienced BBC staffers. But I can easily imagine having to deal with someone in the chain demanding that the uncanny be made explicit, because "that's what the audience will want."

As far as creating soundscapes is concerned, that's kind of interesting. Prior to my first BBC sale I'd written drama for a commercial radio station in Manchester. It was a music station but they'd made a commitment in their franchise application to deliver scripted content. We made the episodes as a kind of co-operative, in the sense of everyone mucking-in and no money. Tony Hawkins was their commercials producer, and he produced. Pete Baker was the breakfast DJ and he handled the technical side. Our cast was drawn from the actors and voiceover people we worked with every day (I was working in Granada's Presentation Department, just down the road). Pete devised a method by which we'd use our limited time with the actors to get a clean voice recording, and then he'd prepare all the sound effects on the instant-start cartridges used for commercials and jingles. Then he'd re-record the voice track through the DJ's desk in the station's unused backup studio, varying the acoustics with equalisation and playing in all the effects in real time.

It was a different situation at the BBC. There it was a rehearse-record system. Different parts of the studio were furnished in different ways to produce different kinds of sound quality, and effects were either created live with props by a studio manager, or played-in from pre-cued vinyl recordings on one of a bank of turntables. Watching it all come together was like some great elaborate ballet resulting in auditory magic. This was my words getting the historic BBC treatment and I was living the dream. But Pete's method was ahead of its time and gave a comparable result, I've always thought.

American radio drama was a quite different beast. When I imagine the kind of BBC drama I grew up with, I think of dignified thespians reading in a studio. But you listen to American 'old time radio' shows from the archives and they're like whirlwind rollercoaster rides with live music and a constant rain of shocks, stings, and climaxes. They're great fun but at the end of it you sometimes realise that it was all in the ride and nothing much of any weight has been said. The ideal is to try for something with a little more literary weight but still with that cinematic momentum.

I'd say that a good horror radio actor is one who'll go for the human truth in the scene where a lesser actor would fall into the trap of playing it for effect. Valentine Dyall – the original Man in Black, with whom I had the pleasure of working when I wrote for Doctor Who – let his natural gravitas do the job. Edward De Souza played it differently but just as effectively, by being sincere and not attempting to 'do creepy'. It's worth remembering that Vincent Price – another great radio voice – gave one of his career-best performances when, in Witchfinder General, he was shorn of all the tics and tricks that had carried him though many a crappy B-movie.

It's only looking back that I realise how fortuitous my career timing was. With just one spec Saturday Night Theatre script it was like I stepped into radio's National Theatre. My very first producer (on Radio 4's The Humane Solution) was the legendary John Tydeman, who'd pretty much launched the careers of Joe Orton and Tom Stoppard. He was head of drama and led a very small team of highly experienced producers. Martin Jenkins did my next (An Alternative to Suicide) and I think with one exception he produced everything I wrote for BBC radio thereafter. We got on really well. While I was still working for Granada he came up to Manchester and I took him to see the outdoor set of Coronation Street, of which he was a fan. But he obviously enjoyed the fact that my stuff was anything but social realism, and that it gave him opportunities to push the medium in all kinds of unusual ways. On Alternative, which was a science fiction piece, I can remember the studio managers wiring up every piece of weird and extreme equipment in the building, tying up every channel and turntable. When I had to leave for my train they were still bringing in more.

On the half-hour Man in Blacks, I'd write the framing narration and it was understood that Martin would rewrite it for his needs. Those episodes now seem to be in constant repertory on Radio 4 Extra. Audio horror has an advantage, in that we're unsettled by incomplete information. Who's outside? What's making that noise? The moment you switch the lights on to see, that entire little universe of uncertainty collapses into something quantified. But with audio horror there's always something legitimately withheld.

I suppose if there's a weakness, it's that a lot of people imagine that an explicit visual trumps a quiet suggestion. If hearing someone scratching at your door is scary, the logic goes, then surely being confronted by them must be scarier still. I never really had to modify my writing because there was a very short note-giving chain and the people I was working with were all trained and experienced BBC staffers. But I can easily imagine having to deal with someone in the chain demanding that the uncanny be made explicit, because "that's what the audience will want."

As far as creating soundscapes is concerned, that's kind of interesting. Prior to my first BBC sale I'd written drama for a commercial radio station in Manchester. It was a music station but they'd made a commitment in their franchise application to deliver scripted content. We made the episodes as a kind of co-operative, in the sense of everyone mucking-in and no money. Tony Hawkins was their commercials producer, and he produced. Pete Baker was the breakfast DJ and he handled the technical side. Our cast was drawn from the actors and voiceover people we worked with every day (I was working in Granada's Presentation Department, just down the road). Pete devised a method by which we'd use our limited time with the actors to get a clean voice recording, and then he'd prepare all the sound effects on the instant-start cartridges used for commercials and jingles. Then he'd re-record the voice track through the DJ's desk in the station's unused backup studio, varying the acoustics with equalisation and playing in all the effects in real time.

It was a different situation at the BBC. There it was a rehearse-record system. Different parts of the studio were furnished in different ways to produce different kinds of sound quality, and effects were either created live with props by a studio manager, or played-in from pre-cued vinyl recordings on one of a bank of turntables. Watching it all come together was like some great elaborate ballet resulting in auditory magic. This was my words getting the historic BBC treatment and I was living the dream. But Pete's method was ahead of its time and gave a comparable result, I've always thought.

American radio drama was a quite different beast. When I imagine the kind of BBC drama I grew up with, I think of dignified thespians reading in a studio. But you listen to American 'old time radio' shows from the archives and they're like whirlwind rollercoaster rides with live music and a constant rain of shocks, stings, and climaxes. They're great fun but at the end of it you sometimes realise that it was all in the ride and nothing much of any weight has been said. The ideal is to try for something with a little more literary weight but still with that cinematic momentum.

I'd say that a good horror radio actor is one who'll go for the human truth in the scene where a lesser actor would fall into the trap of playing it for effect. Valentine Dyall – the original Man in Black, with whom I had the pleasure of working when I wrote for Doctor Who – let his natural gravitas do the job. Edward De Souza played it differently but just as effectively, by being sincere and not attempting to 'do creepy'. It's worth remembering that Vincent Price – another great radio voice – gave one of his career-best performances when, in Witchfinder General, he was shorn of all the tics and tricks that had carried him though many a crappy B-movie.

Published on October 15, 2012 09:54