Geoff Nicholson's Blog, page 46

April 25, 2017

A BRUTAL WALK IN THE SUN

Now that I’m back in Los Angeles, I’ve been walking around looking for signs of Brutalist architecture. There are certainly plenty of ugly buildings in L.A., some of them brutal with a small b, but I’m not sure how many classify as genuinely Brutalist in the grander sense.

The website for the Royal Institute of British Architects has a section labeled, “What to look for in a Brutalist building,” and goes on to list:1. Rough unfinished surfaces

2. Unusual shapes

3. Heavy-looking materials

4. Massive forms

5. Small windows in relation to the other parts

No mention there of concrete, which surprised me: Brutalism supposedly got its name from Le Corbusier who spoke of “breton brut” – i.e. raw concrete, and L.A. certainly has concrete buildings. Various local online pundits also offer lists of Brutalist buildings in L.A.. These vary considerably and include: The American Cement Building:

The La Brea Tar Pits Museum:

The Japanese American Cultural & Community Center:

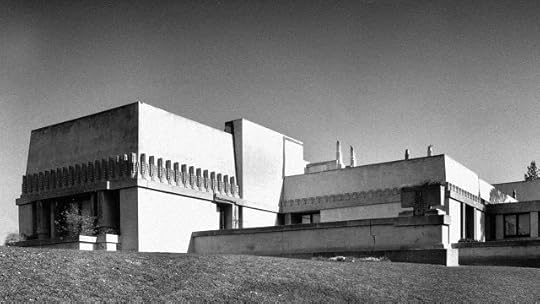

Even Frank Lloyd Wright’s Hollyhock House.

I’ve walked past, and around, and even inside, all of these at some time or another and I never thought they constituted Brutalism. They all strike me as rather friendly buildings, but maybe Brutalism gets softened by the California sunshine, the blue skies, the palm trees.

However, I recently a walk I recently did from Hollywood to Larchmont Village (5 or 6 miles round trip) pitched up some examples that might get a person thinking about the real meaning of brutality in these matters.This apartment block on Bronson Avenue certainly has heavy-looking materials

and strangely small windows in relation to the other parts; no unusual shapes though:

These buildings on Santa Monica Boulevard have no windows at all, but they do have mass, and certainly have heavy looking materials, although one of them is decorated with those elongated stars which would be unthinkable to Brutalist hardliners:

This carpet warehouse on Gower Street looks brutal as all getout, and I believe is made of concrete blocks:

But I can see that you might argue these things are scarcely architecture at all, they’re just buildings, and not so much brutal but just crude. However, just above Beverley Boulevard, on Larchmont Boulevard, is the Larchmont Medical Building, built by Welton Becket and Associates, “real” architects too be sure, completed in 1965.

Welton Becket was also responsible for the Capitol Building and the Theme Building at LAX – so not the most committed to Brutalism but I think this building fits the bill pretty well: big, concrete, blockish, the forms not so much unusual as uncompromising, but again rather friendlier than hardcore Brutalism.

I like it a lot. It’s also a place I’ve been to have root canal work, I seem to recall the main entrance lobby being tiled in blood red marble, but my memory made be failing me there. I was expecting brutality in the dentist's chair, and it turned out to be considerably less brutal than you might imagine.

The website for the Royal Institute of British Architects has a section labeled, “What to look for in a Brutalist building,” and goes on to list:1. Rough unfinished surfaces

2. Unusual shapes

3. Heavy-looking materials

4. Massive forms

5. Small windows in relation to the other parts

No mention there of concrete, which surprised me: Brutalism supposedly got its name from Le Corbusier who spoke of “breton brut” – i.e. raw concrete, and L.A. certainly has concrete buildings. Various local online pundits also offer lists of Brutalist buildings in L.A.. These vary considerably and include: The American Cement Building:

The La Brea Tar Pits Museum:

The Japanese American Cultural & Community Center:

Even Frank Lloyd Wright’s Hollyhock House.

I’ve walked past, and around, and even inside, all of these at some time or another and I never thought they constituted Brutalism. They all strike me as rather friendly buildings, but maybe Brutalism gets softened by the California sunshine, the blue skies, the palm trees.

However, I recently a walk I recently did from Hollywood to Larchmont Village (5 or 6 miles round trip) pitched up some examples that might get a person thinking about the real meaning of brutality in these matters.This apartment block on Bronson Avenue certainly has heavy-looking materials

and strangely small windows in relation to the other parts; no unusual shapes though:

These buildings on Santa Monica Boulevard have no windows at all, but they do have mass, and certainly have heavy looking materials, although one of them is decorated with those elongated stars which would be unthinkable to Brutalist hardliners:

This carpet warehouse on Gower Street looks brutal as all getout, and I believe is made of concrete blocks:

But I can see that you might argue these things are scarcely architecture at all, they’re just buildings, and not so much brutal but just crude. However, just above Beverley Boulevard, on Larchmont Boulevard, is the Larchmont Medical Building, built by Welton Becket and Associates, “real” architects too be sure, completed in 1965.

Welton Becket was also responsible for the Capitol Building and the Theme Building at LAX – so not the most committed to Brutalism but I think this building fits the bill pretty well: big, concrete, blockish, the forms not so much unusual as uncompromising, but again rather friendlier than hardcore Brutalism.

I like it a lot. It’s also a place I’ve been to have root canal work, I seem to recall the main entrance lobby being tiled in blood red marble, but my memory made be failing me there. I was expecting brutality in the dentist's chair, and it turned out to be considerably less brutal than you might imagine.

Published on April 25, 2017 09:48

April 21, 2017

WALKING ABSURDLY

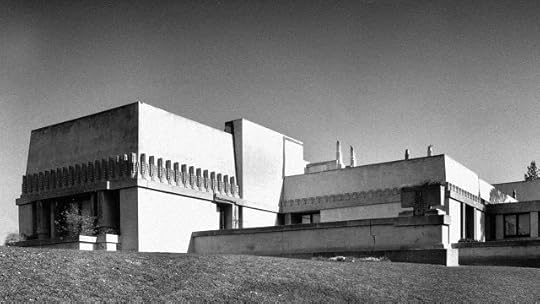

It’s a very long time since I first read Albert Camus’s L’Etranger. It remains the only book I’ve ever read from beginning to end in French: and it was in a class at school. Rereading it now I see there is some walking in it, after all Meursault is walking on the beach when he commits the murder.

Surprisingly perhaps, there are a couple of sentences that I’ve remembered over the years. They come towards the end of the book when Meursault is in prison. To save everybody’s blushes I’ll quote the Penguin Classics translation by Sandra Smith.”I realized then that a man who had only lived a single day could easily live a hundred years in prison. He would have enough memories to keep him from getting bored.”I still think it’s a great couple of sentences, although now that I think about it I don’t believe that boredom per se would be the biggest problem I’d have in prison.

Anyway, arriving at that sentence again I find that it comes at the end of a longish paragraph in which Meursault does indeed try to find a cure for boredom. “I finally stopped being bored altogether from the moment I learned how to remember. Sometimes I started thinking about my bedroom and I would imagine starting at one end and walking around it in a circle while mentally listing all the things I passed.”

Well, knock me down with a feather: you (or at least I) can’t read this without being reminded of Xavier de Maistre’s Voyage Around My Room (Voyage autour de ma chamber - which I have not read in French), the hero of which does indeed walk around his room looking at his possessions, and then goes on voyages of memory, although of course in this case the objects are actually there there.

Did Camus read de Maistre? I can’t find any hard evidence that he did - although Camus is not exactly an open book to me. But in the correspondence of Camus there’s this – a postcard from Camus to “JG” “M. Jacob sent me my horoscope. I am side by side with people as remarkable as Luther and Xavier de Maistre.” Online sources in fact suggest they didn’t share anything like the same birthday, but I suppose “side by side” is open to interpretation..

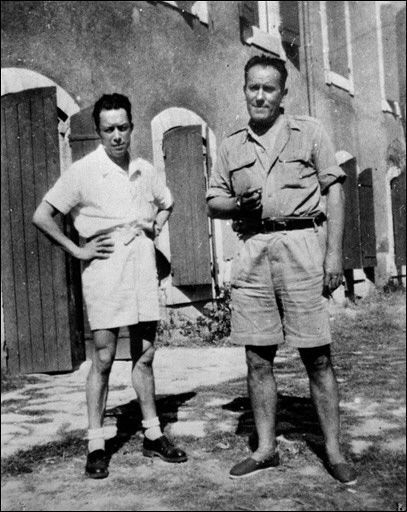

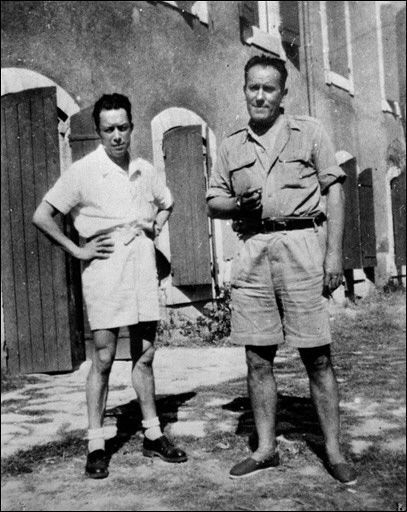

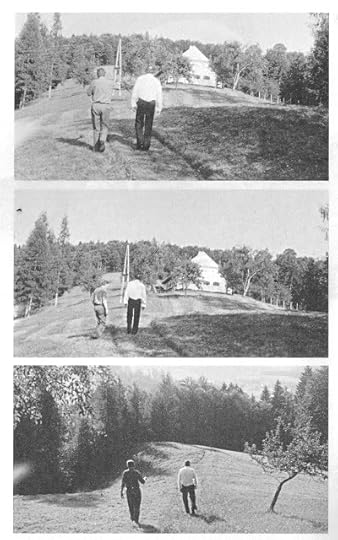

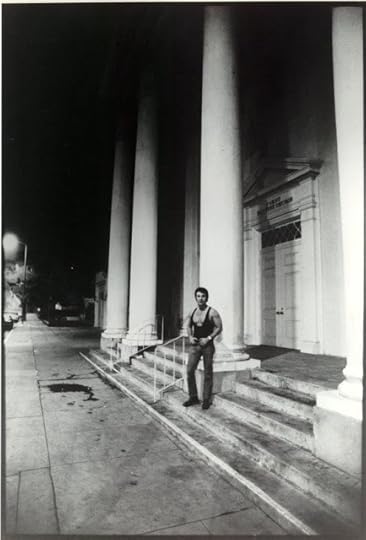

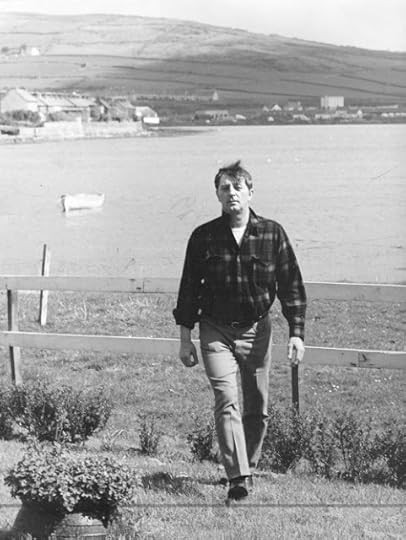

It's not all that easy to find photographs of Camus walking, but there’s this: I think he’s rehearsing a play:

Surprisingly perhaps, there are a couple of sentences that I’ve remembered over the years. They come towards the end of the book when Meursault is in prison. To save everybody’s blushes I’ll quote the Penguin Classics translation by Sandra Smith.”I realized then that a man who had only lived a single day could easily live a hundred years in prison. He would have enough memories to keep him from getting bored.”I still think it’s a great couple of sentences, although now that I think about it I don’t believe that boredom per se would be the biggest problem I’d have in prison.

Anyway, arriving at that sentence again I find that it comes at the end of a longish paragraph in which Meursault does indeed try to find a cure for boredom. “I finally stopped being bored altogether from the moment I learned how to remember. Sometimes I started thinking about my bedroom and I would imagine starting at one end and walking around it in a circle while mentally listing all the things I passed.”

Well, knock me down with a feather: you (or at least I) can’t read this without being reminded of Xavier de Maistre’s Voyage Around My Room (Voyage autour de ma chamber - which I have not read in French), the hero of which does indeed walk around his room looking at his possessions, and then goes on voyages of memory, although of course in this case the objects are actually there there.

Did Camus read de Maistre? I can’t find any hard evidence that he did - although Camus is not exactly an open book to me. But in the correspondence of Camus there’s this – a postcard from Camus to “JG” “M. Jacob sent me my horoscope. I am side by side with people as remarkable as Luther and Xavier de Maistre.” Online sources in fact suggest they didn’t share anything like the same birthday, but I suppose “side by side” is open to interpretation..

It's not all that easy to find photographs of Camus walking, but there’s this: I think he’s rehearsing a play:

Published on April 21, 2017 07:44

April 18, 2017

THE CANAL AND THE CARNAL

The issue before last of the London Review of Books contained a piece by Iain Sinclair, titled “The Last London.”

Iain isn’t happy about the current state of London, which comes as no great surprise: is anybody? However, even walking alongs the canals of East London can be a source of distress. He writes, “Between Victoria Park, the first of the parks opened for the people, and Broadway Market, worlds collide. Two young mothers were texting and being yapped at by older kids, while the youngest child circled on her scooter. There’s a gentle slope down to the canal and the scooter picked up momentum, until the child disappeared over the edge, between two narrowboats, straight into the water. Fortunately, a morning cyclist was stepping ashore. He grabbed the child by the hair. All was well. A little further down the canal, where the path goes under a railway bridge, the mad pumping rush of the peloton swooped through – and a guy on one of those very thin-wheeled bikes was nudged into the soup. Right under, gasping and choking, still in the saddle. I helped to pull him out.”

This did sound a bit action-packed for a Sinclair drift, but I didn’t hold Sinclair personally responsible. However, at least one reader sort of did. A letter duly appeared in the subsequent issue of the LRB, from Giacinto Palmieri, London E2, who writes:“Like Iain Sinclair, I too walk on the canal path between Victoria Park and Broadway Market, but in many years of doing so I’ve never seen anybody fall into the canal. Sinclair, on the other hand, reports witnessing two such episodes, apparently within a short interval of time. Correlation doesn’t entail causation, but I can’t help asking whether these incidents might be correlated with the presence of a psychogeographer wandering dreamily in search of evocative connections in the middle of the path.”

Psychogeography, it's always trouble.

It’s hard to think of canals and east London without also thinking about Lee Rourke’s novel The Canal. Walking seems to be start of all the troubles in that book. “I simply awoke one morning and decided, rather than walk to work as normal I’d walk to the canal instead.”The hero sees and experiences all sorts or horrible things canalside, although admittedly the worst of them happen when he stops walking and sits on a bench where he’s menaced by The Pack Crew, a very bad lot. They throw somebody’s motor scooter into the water, assault his girlfriend, and also try to kill swans with a bow and arrow. Yep, canals can be mythical places.

Here in Los Angeles I’m not sure we even have "real" canals. They exist in Venice, but Venice isn’t really Los Angeles, and the canals aren't really canals. Here’s something – definitely not a canal, could be an aqueduct, could be a concrete creek – in Culver City, which I thought was worth a picture:

Iain isn’t happy about the current state of London, which comes as no great surprise: is anybody? However, even walking alongs the canals of East London can be a source of distress. He writes, “Between Victoria Park, the first of the parks opened for the people, and Broadway Market, worlds collide. Two young mothers were texting and being yapped at by older kids, while the youngest child circled on her scooter. There’s a gentle slope down to the canal and the scooter picked up momentum, until the child disappeared over the edge, between two narrowboats, straight into the water. Fortunately, a morning cyclist was stepping ashore. He grabbed the child by the hair. All was well. A little further down the canal, where the path goes under a railway bridge, the mad pumping rush of the peloton swooped through – and a guy on one of those very thin-wheeled bikes was nudged into the soup. Right under, gasping and choking, still in the saddle. I helped to pull him out.”

This did sound a bit action-packed for a Sinclair drift, but I didn’t hold Sinclair personally responsible. However, at least one reader sort of did. A letter duly appeared in the subsequent issue of the LRB, from Giacinto Palmieri, London E2, who writes:“Like Iain Sinclair, I too walk on the canal path between Victoria Park and Broadway Market, but in many years of doing so I’ve never seen anybody fall into the canal. Sinclair, on the other hand, reports witnessing two such episodes, apparently within a short interval of time. Correlation doesn’t entail causation, but I can’t help asking whether these incidents might be correlated with the presence of a psychogeographer wandering dreamily in search of evocative connections in the middle of the path.”

Psychogeography, it's always trouble.

It’s hard to think of canals and east London without also thinking about Lee Rourke’s novel The Canal. Walking seems to be start of all the troubles in that book. “I simply awoke one morning and decided, rather than walk to work as normal I’d walk to the canal instead.”The hero sees and experiences all sorts or horrible things canalside, although admittedly the worst of them happen when he stops walking and sits on a bench where he’s menaced by The Pack Crew, a very bad lot. They throw somebody’s motor scooter into the water, assault his girlfriend, and also try to kill swans with a bow and arrow. Yep, canals can be mythical places.

Here in Los Angeles I’m not sure we even have "real" canals. They exist in Venice, but Venice isn’t really Los Angeles, and the canals aren't really canals. Here’s something – definitely not a canal, could be an aqueduct, could be a concrete creek – in Culver City, which I thought was worth a picture:

Published on April 18, 2017 21:26

April 15, 2017

WALKING BRUTALLY

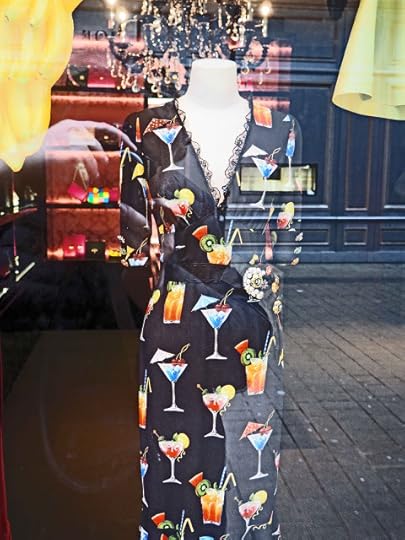

The first time I went to London I was 16 years old. It was a long weekend, going down from Yorkshire with my parents and some family friends. We were rubes. We didn’t know what anything was and we didn’t even particularly know what we wanted to see. We knew the names of some familiar places: Greenwich, Birdcage Walk, the Tower of London and we went to all of them. We walked ourselves into the ground. And somehow - I think we must have taken a boat ride along the Thames - we ended walking around the Southbank, including the Hayward Gallery, which I now realize had only been completed the previous year. Below are some rather badly processed black and white pics I took on that visit.

I liked the Hayward, I think, because it seemed new and modern and different, though I certainly had no idea the architectural style was called Brutalism, whether old or new.

My dad, on the other hand, was horrified. He was a joiner, and by then a foreman for the council on various building sites around Sheffield. He looked at the concrete finish of the Hayward, with the impressions of wood grain, and what he saw was “shuttering” familiar enough from his own work – wooden planks used to make a form that contained concrete, when you were making a foundation or a trench. It was the kind of work you gave to joiners who turned up at the site and weren’t skilled enough to do anything else.

The idea that you’d leave this visible on the outside of a finished building was just incomprehensible to him. Of course he was also well aware of Sheffield’s Park Hill flats, another bit of Brutalism, and he found them pretty horrifying too. He died long before they became fashionable and desirable, and he’d have found that incomprehensible too.

As you see from my photographs, there was an exhibition of pop art on at the Hayward when we were there – but I couldn’t tempt any of the others inside.

One way or another I’ve spent a fair amount of time over the years walking in and around the Hayward, going to exhibitions, working there briefly as a security guard. And during a particularly grim period when I taught creative writing to fashion students (terrible in all the ways you’d imagine and in some you couldn’t even conceive of) I used to go walking there after work, in an attempt to decompress. Somewhere along the line I did realize, having read my Rayner Banham, that this was indeed an example of Brutalism, possibly even New Brutalism.

When I first started living in London I also spent a certain amount of time in the Barbican, on the way to and from exhibitions, films, concerts, and so on. But it was an odd thing, the Barbican felt far stranger, for more alien, than the Hayward. It didn’t feel like the “real” London.

I wonder if that has something to do with the fact that when you’re at the Hayward you can look out and see various familiar London sights – the river, St Paul’s, Tower Bridge. Once you’re inside the Barbican (and finding your way in through that hideous fume-filled tunnel can be quite a challenge), it’s as though you’re in a separate, hermetic world. You could be anywhere.

Well, we’re all fans of Brutalism these days and the Barbican is a place where a lot of people like to be. So when I was in London last month, I went along there so see how it felt these days. It felt fine. And there were absolutely swarms of people wandering around taking pictures, including a whole art school class it seemed. Of course they, by which I probably mean we, found plenty to photograph. We all know what the beauty of Brutalism looks like.

And in many ways it’s a great place to walk, or at least drift. Finding your way when you’re in a hurry can be a bit of a nightmare, but if nothing else, once you’ve penetrated the fortress you’re entirely protected from traffic. This is a place for walkers.

There’s something called the “High Walk” which takes you along the top level of the complex, and you walk along some fairly inscrutable corridors, and I dare say “pedways,” where you’re likely to be one of only a very few people. It’s interesting and intriguing, and definitely photogenic, and filmic in a noirish kind of way but it’s not exactly friendly or comfortable. We could argue about whether the experience is literally brutal, but it’s certainly bleak. This looks like a location where bad things can happen. You wouldn’t want to be walking up there alone at night, in the shadows, with all those echoing footsteps and blind corners. Or maybe you would. In the daytime however it’s totally exhilarating.

My visit to London wasn’t meant to be a Brutalist vacation but somehow it turned into one. I ended up spending a couple of nights in the St. Giles Hotel, on Tottenham Court Road.

I’ve walked past it hundreds of times and never paid much attention to it,. But now, looking through Brutalist eyes, it appeared to be some some kind of Brutalist masterpiece, taking up a whole block: huge, angular, solid but somehow sprightly. The rooms are small but I think they all give views over London, views that are inevitably framed by concrete. Who’d have it any other way?

Published on April 15, 2017 13:13

April 3, 2017

ACTION STRASSE

I’m sure it must be possible to walk the streets of Vienna without whistling or humming “The Blue Danube,” but for a first-time visitor like me, it’s not easy: Air Austria even plays it over the aircraft’s p.a. system as you’re deplaning. Other alternatives include the Third Man theme, or Ultravox’s “Vienna” – and the latter does have some oblique lyrics that mention walking but of course the only line anybody ever really remembers is “This means nothing to me – Vienna,” which seems a bit negative.

I was in Vienna for the launch of Wiener Blut. What’s that you ask? “Wiener Blut is an ambitious collaboration to photograph every street in Vienna. As well as creating a work of art for an exhibition in 2018, we’ll be producing a visual social documentary of Vienna in 2017/18.”It is a cousin of “Bleeding London,” the project and exhibition based on my novel of the same name, which photographed every street in London: both organized by Del Barrett. (Wiener Blut, I know now, is also the name of a waltz by Strauss).

At the Vienna launch I made a short, clumsy speech about walking and observing and photographing. I said that every street is interesting if you look at it the right way. There are fascinations, marvels, on every block, probably on every square inch. I still tend to believe this is true.

After, and indeed before, the launch I wandered the streets of Vienna, sometimes alone, sometimes with others, looking at stuff, taking pictures, feeling the vibe, sometimes getting lost. You don’t need me to make too many superficial remarks about the wonders of Vienna but let me share one or two things.

Walking down the street from my hotel, I came across a place named f*c, which I think stands for Frauencafe, a women’s (or at least not a men’s) café. There was a mission statement in the window, in both German and English. The English one read, in part, “If you are a cis gendered man, please leave the space without having to be asked.” This seemed to anticipate an unlikely set of events, it seemed to me; that a cis gendered man (I guess that’s me) might enter the place, by accident, or perhaps to see how great it was, or in any case without having read the sign in the window, but then he would have to leave immediately before he was asked, but how would he know to do that unless he'd read the sign in the window, and if he'd read the sign in the window then surely he wouldn't enter, would he? And what happened if he didwait to be asked? Would that be so terrible? In any case the place looked closed every time I went past.

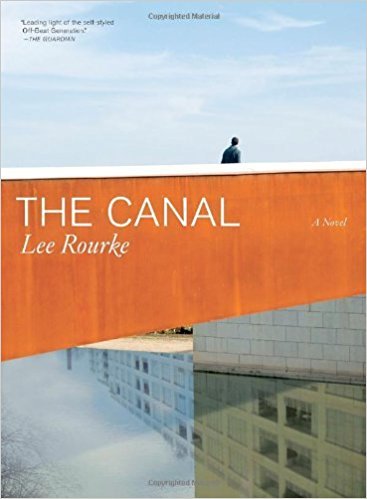

Of course, like any good tourist, I gazed into shop windows as I walked around the city. I swear I saw a shop that sold only exotic booze and light bulbs. You can imagine the thought process: people are always going to need booze, people are always going to need light bulbs – there’s your business model. I also saw this cocktail dress printed with images of rather lurid cocktails, not a look that everybody could pull off, I’d say. And I imagine probably not what they're wearing in the Frauencafe, but who knows?

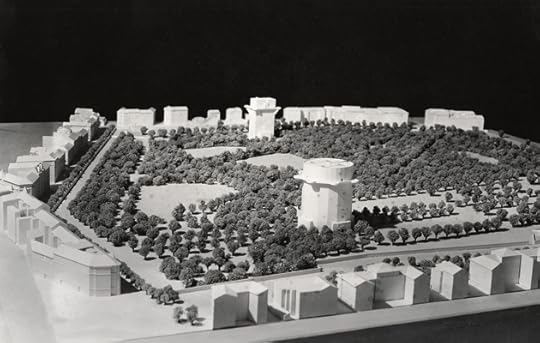

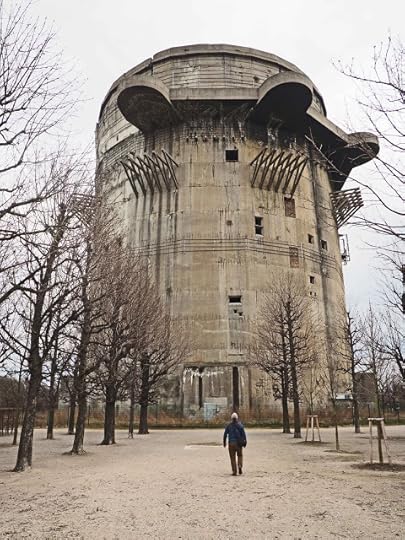

And then there was a walk around the Flak Towers – I hadn’t known about them, and I definitely should have. Building started in 1942 on Hitler’s instructions, designed by Professor Friedrich Tamms, constructed using forced labor, and they were functional by 1944, which might be thought to be a bit late. There were guns at the top on the outside, and an air raid shelter inside, and lord knows they were solid and impregnable. They’re still wildly impressive and in their totalitarian brutality.

Jan Tabor, the Czech-Austrian architect and architectural theorist wrote, “Without wanting to deny the military purposefulness of these buildings completely, they were conceived from the beginning as above all ‘mood architecture’ … They are monuments of and for all times. As a result they are without utilitarian value in the usual sense. They are as useless as plastic art. But they were carriers of an idea, an elementary feeling for power, stability and will to live.”

As I walked around them, in what is now a very pleasant public park, it seemed that the local walkers ignored them completely. Maybe they were too familiar with them, or maybe they hated them and preferred not to look. Personally I kept thinking that Banksy might find a handy way of using those towers.

And speaking of Viennese blood, I did see this graffito which I believe translates as “Jesus pisses your blood,”

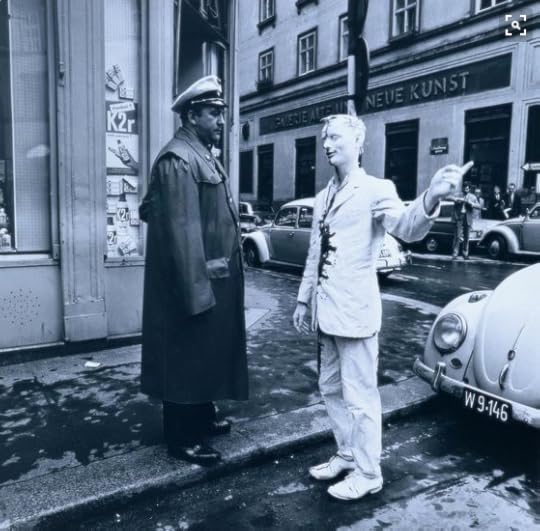

It made me think of the Vienna Actionists, a well-dodgy bunch of 1960s artists, performance artists we’d call them today, whose “actions” tended to involve blood, excreta, cruelty to animals, blasphemy and sex (most of it unerotic, I’d say, but these things are subjective).

It was all about breaking taboos and making Austrians face up to their country’s embrace of Nazism in World War Two, apparently. I think you’re entitled to wonder how rolling around in animal entrails symbolizes these matters but it was a different age. Hard to find an image of this stuff that I’d want in my blog but here’s a comparatively mild one.

However, if you inevitably walk in Vienna in the footsteps of Strauss and Bernhard and Freud, you also walk in the footsteps of Günter Brus, Hermann Nitsch, Rudolf Schwarzkogler, and Otto Muehl, the four main Actionists. Muehl was the best known and most spectacularly appalling of them (that's him in the pic above), he was also the leader of a radical commune, as was the style in those days, and a thing that seldom ends well.

Günter Brus seems, in some ways, to have been as bad as any of them. In 1968 he went to jail as a result of Body Analysis Action no.33, which involved cutting himself with a razor-blade, drinking his own urine, rubbing his naked body with shit, and masturbating while singing the Austrian anthem. He got six months for “degrading the symbols of the State.” I can’t believe he was surprised.

Before that however, in 1965, he performed “Vienna Walk” (Kopfbemalung, Aktion, Wien) a fairly vanilla-seeming piece in which he walked through the city, fully clothed but painted all white, with a black line, that looks quite a bit like medical stitches, dividing his body and his suit into two vertical halves, claiming himself to be a “living painting”. Sounds pretty harmless but he still got arrested.

Otto Muehl in due course went to jail on charges of having sex with under age girls in his commune. Günter Brus was awarded the Grand Austrian State Prize in 1997. Maybe the Austrian State is a mass of contradictions.

Published on April 03, 2017 15:45

March 31, 2017

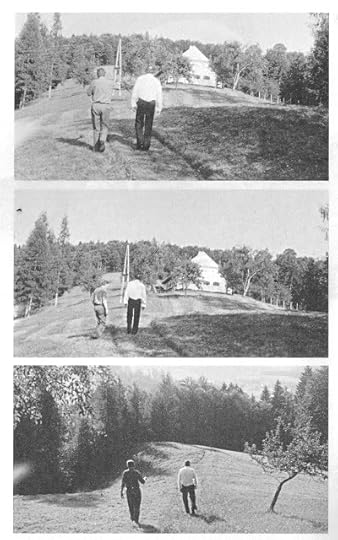

WALKING WITH MARTIN AND THOMAS

I’ve been walking again, in London, with my old friend Dr. Martin Bax. Martin is 84 years old, suffering from dementia, and is sinking fast. He seems to be in good physical health, lives in his own home, and is well looked after; even so it feels as though his mind and personality are evaporating, as though there’s less and less of the person I used to know, although what remains is still very much the man himself. An example: Martin told me he’d only ever voted once in his long life. “That’s because I’m an anarchist,” he said. “Anarchists don’t vote.”“What do anarchists do?” I asked. “They don’t do anything,” he replied. “That’s the best part about being an anarchist.”

Martin walks every day, more often than not by himself. He has a new carer who told me she was initially amazed and alarmed by this, and so she did a “risk assessment” which consisted of following him up the road, and concluded that he was a safe enough walker.

Martin only has one walking route these days, along the road where he lives, which has a bit of an upward incline, then at the top of the road he turns left and heads down a considerably steeper hill, heading to a little park, usually deserted next to some allotments, and giving a fine view of Alexandra Palace away on a distant hill.

When I’m with him we sit on a bench for a little while, and then go back, the return journey being somewhat harder because of the steepness of the hill. Martin takes his time, and has certain places where he stops, rests and supports himself, first on a tree and then on a post, always the same ones it seems, and then he soldiers on. The trip is less than a mile all told and takes a little less than an hour.

When I’m with him we sit on a bench for a little while, and then go back, the return journey being somewhat harder because of the steepness of the hill. Martin takes his time, and has certain places where he stops, rests and supports himself, first on a tree and then on a post, always the same ones it seems, and then he soldiers on. The trip is less than a mile all told and takes a little less than an hour.

It was spring in London and the city looked great. As we walked, Martin was fascinated, and so was I, by some markings on the pavements of his neighbourhood. Somebody had been marking broken or uneven paving stones, and drawing outlines around the base of trees.

We assumed it was a council worker who’d done it. I thought that wouldn’t be such a bad job, walking around London marking problems on the pavement, although now that I think about it, I suppose it could have been a concerned citizen drawing people’s attention to ground level problems. Either way it did create a strange and appealing affect, especially for lovers of the terraglyph.

Martin walks slowly, of course, and he says that a time will come when he won’t be able to do the walk at all. This is surely true, and a melancholy thought. It would be nice to keep walking to the end. Some do, some don’t.

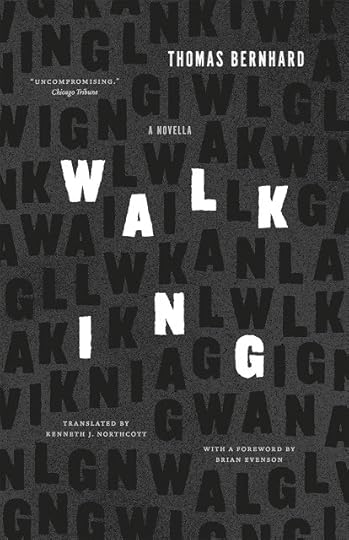

It so happened that while I stayed with Martin, I was rereading Thomas Bernhard’s novella Walking prior to a trip to Vienna.

The piece is only intermittently about walking. More often it’s about the nature of thought, the nature of madness, the horrors of the Austrian State, the repulsiveness of children, and there’s also quite a lot of stuff about trousers. All this is pretty darn hilarious, although I think it also becomes in the end, somehow, absolutely heartbreaking.

And at one point Bernhard’s book does discuss the relationship between walking and thinking. Of course it’s done in thoroughly Bernhardian fashion.“Whereas we always thought we could make walking and thinking into a single total process, even for a fairly long time, I now have to say that it is impossible to make walking and thinking into one total process for a fairly long period of time. For, in fact, it is not possible to walk and to think with the same intensity for a fairly long period of time, sometimes we walk more intensively, but think less intensively, then we think intensively and do not walk as intensively as we are thinking …” and so on.This seems transparently true. The harder we walk, the harder it is to think. Would anybody disagree?

And then later, more intriguingly,“If we observe very carefully someone who is walking, we also knows how he thinks. If we observe very carefully someone who is thinking, we know how he walks … There is nothing more revealing than to see a thinking person walking, just as there is nothing more revealing than to see a walking person thinking, in the process of which we can easily say that we see how the walker thinks just as we can say that we see how the thinker walks …” and so on.

This strikes me as interestingly problematic. And I’m not sure it’s true at all. I know some quite elegant thinkers who walk clumsily. I know some quite elegant walkers who are very clumsy thinkers. Martin’s walking is slow, cautious, plodding but quite determined: he gets where he’s going even if he’s decided he doesn’t want to go very far, and who can blame him. I do wonder what he thinks as he walks. And I wonder what it would be like to spend half an hour inside his head and see how it feels, how he perceives the world, to see if he thinks at all. It is, we all know, quite possible to walk without having a thought in your head.

Martin walks every day, more often than not by himself. He has a new carer who told me she was initially amazed and alarmed by this, and so she did a “risk assessment” which consisted of following him up the road, and concluded that he was a safe enough walker.

Martin only has one walking route these days, along the road where he lives, which has a bit of an upward incline, then at the top of the road he turns left and heads down a considerably steeper hill, heading to a little park, usually deserted next to some allotments, and giving a fine view of Alexandra Palace away on a distant hill.

When I’m with him we sit on a bench for a little while, and then go back, the return journey being somewhat harder because of the steepness of the hill. Martin takes his time, and has certain places where he stops, rests and supports himself, first on a tree and then on a post, always the same ones it seems, and then he soldiers on. The trip is less than a mile all told and takes a little less than an hour.

When I’m with him we sit on a bench for a little while, and then go back, the return journey being somewhat harder because of the steepness of the hill. Martin takes his time, and has certain places where he stops, rests and supports himself, first on a tree and then on a post, always the same ones it seems, and then he soldiers on. The trip is less than a mile all told and takes a little less than an hour.

It was spring in London and the city looked great. As we walked, Martin was fascinated, and so was I, by some markings on the pavements of his neighbourhood. Somebody had been marking broken or uneven paving stones, and drawing outlines around the base of trees.

We assumed it was a council worker who’d done it. I thought that wouldn’t be such a bad job, walking around London marking problems on the pavement, although now that I think about it, I suppose it could have been a concerned citizen drawing people’s attention to ground level problems. Either way it did create a strange and appealing affect, especially for lovers of the terraglyph.

Martin walks slowly, of course, and he says that a time will come when he won’t be able to do the walk at all. This is surely true, and a melancholy thought. It would be nice to keep walking to the end. Some do, some don’t.

It so happened that while I stayed with Martin, I was rereading Thomas Bernhard’s novella Walking prior to a trip to Vienna.

The piece is only intermittently about walking. More often it’s about the nature of thought, the nature of madness, the horrors of the Austrian State, the repulsiveness of children, and there’s also quite a lot of stuff about trousers. All this is pretty darn hilarious, although I think it also becomes in the end, somehow, absolutely heartbreaking.

And at one point Bernhard’s book does discuss the relationship between walking and thinking. Of course it’s done in thoroughly Bernhardian fashion.“Whereas we always thought we could make walking and thinking into a single total process, even for a fairly long time, I now have to say that it is impossible to make walking and thinking into one total process for a fairly long period of time. For, in fact, it is not possible to walk and to think with the same intensity for a fairly long period of time, sometimes we walk more intensively, but think less intensively, then we think intensively and do not walk as intensively as we are thinking …” and so on.This seems transparently true. The harder we walk, the harder it is to think. Would anybody disagree?

And then later, more intriguingly,“If we observe very carefully someone who is walking, we also knows how he thinks. If we observe very carefully someone who is thinking, we know how he walks … There is nothing more revealing than to see a thinking person walking, just as there is nothing more revealing than to see a walking person thinking, in the process of which we can easily say that we see how the walker thinks just as we can say that we see how the thinker walks …” and so on.

This strikes me as interestingly problematic. And I’m not sure it’s true at all. I know some quite elegant thinkers who walk clumsily. I know some quite elegant walkers who are very clumsy thinkers. Martin’s walking is slow, cautious, plodding but quite determined: he gets where he’s going even if he’s decided he doesn’t want to go very far, and who can blame him. I do wonder what he thinks as he walks. And I wonder what it would be like to spend half an hour inside his head and see how it feels, how he perceives the world, to see if he thinks at all. It is, we all know, quite possible to walk without having a thought in your head.

Published on March 31, 2017 10:12

March 11, 2017

WALKING WITH WAUGH

And while we're talking of Waugh and walking, seems he wasn't necessarily

always sympathetic to other promenaders:

always sympathetic to other promenaders:

Published on March 11, 2017 14:04

March 8, 2017

V. AND ME AND OTHERS

I’m never sure how I feel about that old psychogeographic strategy of using a map of one place while walking in another. I mean it seems sort of interesting, but surely once you arrive at the first river or dead end then surely the conceit ends pretty abruptly. (I could be wrong, this isn’t my area.)

But suddenly I find some psychogeography avant la letter in a rather surprising place – in Evelyn Waugh’s travel book Labels. It was his account of the 1929 Mediterranean cruise he took with his wife, who was of course also named Evelyn. One of the places they visited was Malta, and Waugh bought himself a guide book titled Walks in Malta by one F. Weston.

Waugh reports that he enjoyed the book, “not only for the variety of information it supplied, but for the amusing Boy-Scout game it made of sight-seeing. ‘Turning sharply to your left you will notice …’ Mr. Weston prefaces his comments, and there follows a minute record of detailed observation. On one occasion when carrying his book, I landed at the Senglea quay, taking it for Vittoriosa, and walked on for some time in the wrong town, hotly following false clues and identifying ‘windows with fine old mouldings,’ ‘partially defaced escutcheons,’ ‘interesting iron-work balustrades,’ etc., for nearly a quarter of a mile, until a clearly non-existent cathedral brought me up sharp to the realization of my mistake.”

Most of us, without calling ourselves psychogeogarphers, have done something similar on our travels, looked for the right thing in the wrong place, found we were looking at the wrong page of the map, found we weren’t where we thought we were, and so on. Sometimes it feels simply annoying, sometimes we see the funny side, like Waugh, and I suppose once in a while we do experience a Debordian derangement of the sense.

The Waugh episode is quoted in Paul Fussell’s Abroad: British Literary Traveling Between the Wars. It’s a good book, but it contains, uncritically, a very odd quotation from Anthony Burgess, “Probably, (as Pynchon never went to Valetta or Kafka to America) it’s best to imagine your own foreign country. I wrote a very good account of Paris before I ever went there. Better than the real thing.” This comes from an interview in the Paris Review “The Art of Fiction No 48” and as far as I can tell he’s completely wrong about Pynchon, who had surely visited Malta, and especially the capital Valletta, before he wrote about it in V.. Here is a gloriously uninformative jacket:

And I did find this in the Malta Independent, 13 April 2014, an unsigned and unattributed article which describes a lecture delivered by Professor Peter Vassallo, who hails from Valletta and is described as “an eminent authority on British literature.” The article says, though it doesn’t seem to be a direct quotation from the lecturer, “It is ascertained that Pynchon as a seaman in the US navy was in Malta during the Suez build-up, so the Valletta he portrays is a town he knows well, including and especially Strait Street with its bars, brothels and latrine.” Did it really have just the one latrine? Maybe so. In any case it tends to confirms my feeling that Pynchon did know his Malta.

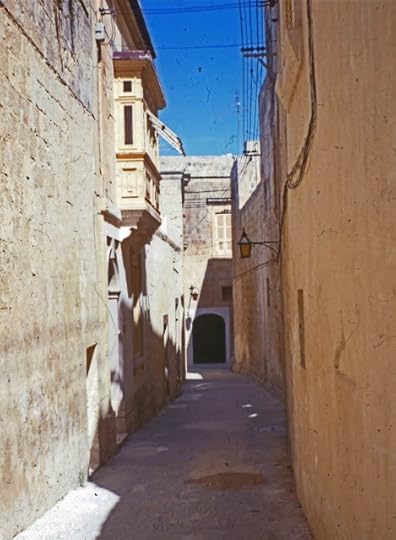

For what it’s worth, I too have been to Malta, with my first wife shortly after we were married. She had lived there for a while because her father had been in the British navy and was stationed there, so she knew parts of the island pretty well. I had certainly read Thomas Pynchon’s V. at the time, but like an idiot I didn’t let it inform my visit to Malta. And I don’t remember us having either a map or a guide book, though surely we must have.

I know we did a lot of traveling on local buses to far-flung bits of the island and then a lot of walking when we got there. It was very good as I recall. I can’t remember much about it, but I'm pretty sure we walked up Strait Street.

I took pictures the ones you see here but they seem odd to me know. I think this was a time when I wanted to take pictures but wasn’t sure what to take pictures of. I’m struck by how few people appear in these pictures, walking or otherwise. The streets surely can’t have been quite as deserted as they appeared here but maybe I was a mad dog walking in the midday sun when everybody was sheltering from the heat. I can't tell you exactly where the pictures were taken but I think most of them were in Valletta.

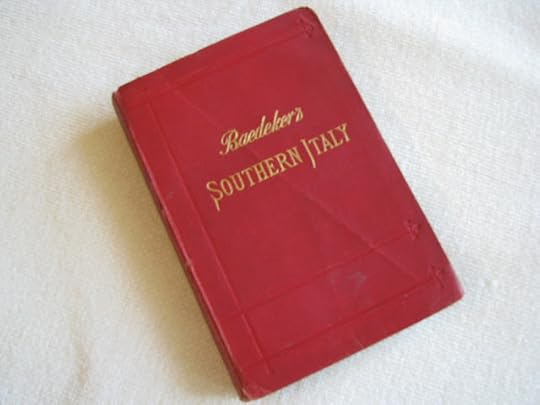

So now I’ve been rereading parts of V.. We have discussed elsewhere whether Pynchon is much of a flaneur, and the jury is still out, but it’s not hard to imagine him drifting through the streets of Valetta, consulting an old Baedeker as he went; it would have been the Southern Italy volume.

And there is this passage in V., chapter 11, “Confessions of Fausto Majistral,” describing Valletta in the blackout during the German bombardment. I suppose a map’s no use in a blackout even if it’s of the place you happen to be.

“A city uninhabited is different. Different from what a "normal" observer, straggling in the dark - the occasional dark - would see. It is a universal sin among the false-animate or unimaginative to refuse to let well enough alone. Their compulsion to gather together, their pathological fear of loneliness extends on past the threshold of sleep; so that when they turn the corner, as we all must, as we all have done and do - some more than others - to find ourselves on the street... You know the street I mean, child. The street of the 20th Century, at whose far end or turning - we hope - is some sense of home or safety. But no guarantees. A street we are put at the wrong end of, for reasons best known to the agents who put us there. But a street we must walk.”

Published on March 08, 2017 17:03

March 2, 2017

A LONG CRUISE ON A SHORT STREET

Nobody would pretend that Selma Avenue in Hollywood is one of the great walking streets, nor one of the great places for urban exploration - it runs for about a mile and a half, east/west, between and parallel to Hollywood Boulevard and Sunset Boulevard. But it’s not without interest, because nowhere is.

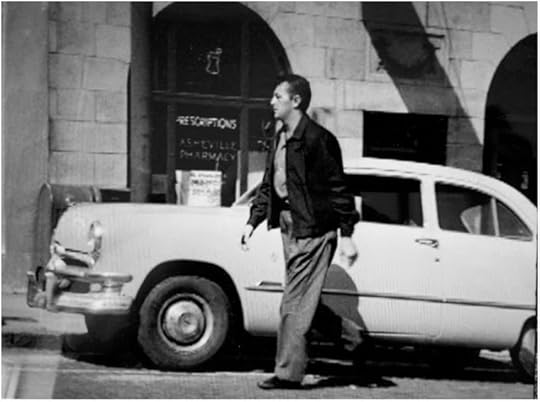

Back in the day Selma used to a be a place where young men, inspired perhaps by Midnight Cowboy, hung out and plied their trade. There’s still a YMCA in the street, but you can’t stay there these days however much fun it might be. This is John Rechy below on the steps of the First Baptist Church of Hollywood, which has stood on Selma in its present form since 1935.

Currently Selma is the site of all kinds of development and redevelopment, and I dare say a truckload of “gentrification.” Restaurants close and are replaced by new ones that don’t necessarily look any better than the old ones, but presumably they have a better business plan. There’s a stylish barber’s shop, a store that sells only vinyl, and there used to be a tent city of homeless people, but they were recently moved on by the cops.

There’s some curious stuff on the sidewalk:

Some curious window treatments:

And there’s this, which may be the best reason for walking along Selma – an amazing example of scarcely improvable, ramshackle, improvised urban infrastructure. It may possibly be a Thomasson (op cit) although possibly not because this thing, however ramshackle and improvised, is actually functional.

As I hope you can see in the above pictures (one mine, one from Google), and I know it's not easy, it’s essentially, two telegraph poles stuck together. There’s one big, tall, fully-formed pole, supporting wires that run high across the street, and then there’s a shorter pole attached to it, accommodating wires that run in a somewhat different direction at a lower level.

Two big, tall, fully-formed poles might have seemed the way to go but apparently the powers that be couldn’t find an extra pole of the required length. They ended up with one that was shorter than the other, that wouldn’t even reach from ground level to the required height of the wires running crosswise.

So what would you do? Well, what they evidently did was attach the short pole and to the big pole but they had to raise it three or four feet off the ground. In order to do that they used brackets and then a length of lumber for support. But even the length of lumber proved too short and so they put a lump of wood underneath that as a shim.

It’s wonderful. It works, I guess. And frankly this is the way I personally do “handyman” projects – ham-fisted but functional. You might imagine the powers that be in Hollywood would operate with more style and skill. The fact that they don’t is somehow charming but also unsettling. Is the whole of Hollywood held together with wire and string? I think we all know the answer to that one.

Back in the day Selma used to a be a place where young men, inspired perhaps by Midnight Cowboy, hung out and plied their trade. There’s still a YMCA in the street, but you can’t stay there these days however much fun it might be. This is John Rechy below on the steps of the First Baptist Church of Hollywood, which has stood on Selma in its present form since 1935.

Currently Selma is the site of all kinds of development and redevelopment, and I dare say a truckload of “gentrification.” Restaurants close and are replaced by new ones that don’t necessarily look any better than the old ones, but presumably they have a better business plan. There’s a stylish barber’s shop, a store that sells only vinyl, and there used to be a tent city of homeless people, but they were recently moved on by the cops.

There’s some curious stuff on the sidewalk:

Some curious window treatments:

And there’s this, which may be the best reason for walking along Selma – an amazing example of scarcely improvable, ramshackle, improvised urban infrastructure. It may possibly be a Thomasson (op cit) although possibly not because this thing, however ramshackle and improvised, is actually functional.

As I hope you can see in the above pictures (one mine, one from Google), and I know it's not easy, it’s essentially, two telegraph poles stuck together. There’s one big, tall, fully-formed pole, supporting wires that run high across the street, and then there’s a shorter pole attached to it, accommodating wires that run in a somewhat different direction at a lower level.

Two big, tall, fully-formed poles might have seemed the way to go but apparently the powers that be couldn’t find an extra pole of the required length. They ended up with one that was shorter than the other, that wouldn’t even reach from ground level to the required height of the wires running crosswise.

So what would you do? Well, what they evidently did was attach the short pole and to the big pole but they had to raise it three or four feet off the ground. In order to do that they used brackets and then a length of lumber for support. But even the length of lumber proved too short and so they put a lump of wood underneath that as a shim.

It’s wonderful. It works, I guess. And frankly this is the way I personally do “handyman” projects – ham-fisted but functional. You might imagine the powers that be in Hollywood would operate with more style and skill. The fact that they don’t is somehow charming but also unsettling. Is the whole of Hollywood held together with wire and string? I think we all know the answer to that one.

Published on March 02, 2017 13:21

February 26, 2017

RAMBLING WITH ROBERT

I’m not sure why it’s taken me till now to find this line from Robert Mitchum about walking, “People think I have an interesting walk. Hell, I'm just trying to hold my gut in.” It’s a great line, and the story of many of our lives as we get older.

Mitchum was talking to Earl Wilson, for the Los Angeles Herald Examiner in 1971, when he would have been aged 54. The previous year he'd made the movie Ryan’s Daughter, and he’s certainly not the slim young man of his youth but really he doesn’t look bad compared with the average 54 year old.

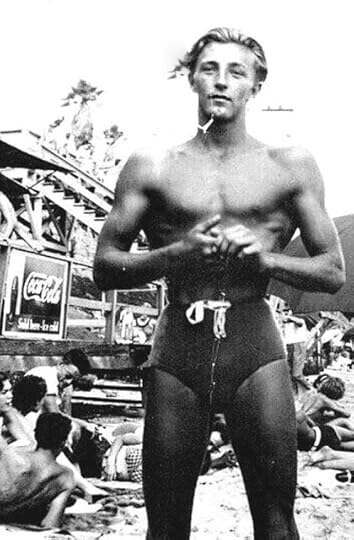

It had all started rather differently, as it usually does:

And he was evidently a man who liked to get his shirt off, whether he was walking or not, I'd say that gut is being rather fiercely held in this picture, from Going Home, actually from 1971.

Equally, he spent much of his career in a well-cut suit and/or a trenchcoat, which would hide many of the gut problems.

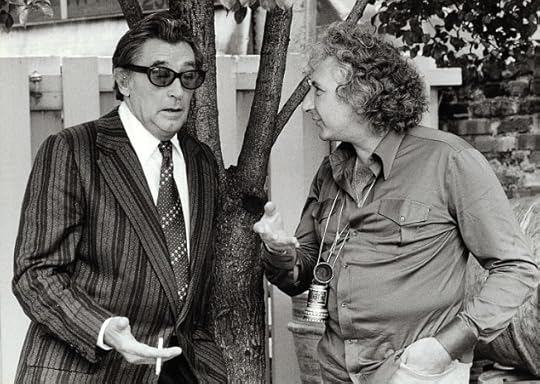

Of course there are times when even a suit can’t completely get the job done, though (inevitably) he's still looking pretty good here, a certainly lot better than Michael Winner:

And sometimes of course a man just sits back and doesn’t even try to hold it in, although that the belt is doing its very best.

And as seen here, there are some walkers who actually prefer to let it all hang out. They ain't no Robert Mitchums. Who the heck is?:

.

.

Published on February 26, 2017 14:54

Geoff Nicholson's Blog

- Geoff Nicholson's profile

- 55 followers

Geoff Nicholson isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.