Geoff Nicholson's Blog, page 43

August 25, 2017

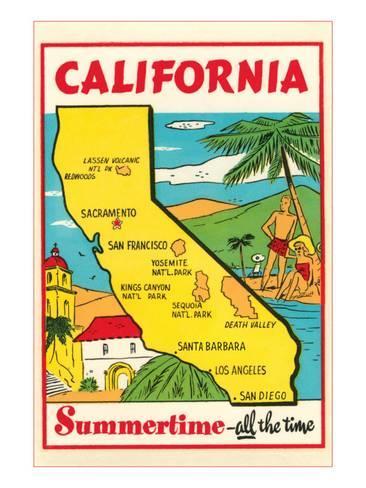

GROUNDED IN CALIFORNIA

Here is probably the best thing I’ve seen while walking in Hollywood in recent times:

It’s an outline of California, right? On Selma Avenue. And I can’t decide whether it’s deliberate, whether some waggish road crew deliberately put it there while filling in a hole of a completely different shape, or whether my pareidolia is just getting out of control.

Of course it could be both

It’s an outline of California, right? On Selma Avenue. And I can’t decide whether it’s deliberate, whether some waggish road crew deliberately put it there while filling in a hole of a completely different shape, or whether my pareidolia is just getting out of control.

Of course it could be both

Published on August 25, 2017 09:57

August 20, 2017

THE PHILOSOPHER'S WALK

“He that endeavors to enter into the Philosopher’s Garden without a key, is like him who would walk without feet.”

The above quotation and image are from a 1617 alchemical “emblem book” by Michael Maier (aka Michael Majerus) titled “Atalanta Fugiens, The Flying Atalanta or Philosophical Emblems of the Secrets of Nature.” It consists of 50 emblems (what we might call epigrams) each with an illustration (by Matthäus Merian) along with a discussion or discourse about the emblem, and then a related piece of music in the form of a fugue.

Alchemy isn’t exactly an open book to me, but that emblem above - “Emblema XXVII” - sounds fair enough. You need a key to alchemy, you need feet for walking. However a couple of observations emerge from looking at that image. First, the fellow there doesn’t seem to be much hindered by the lack of feet. He’s standing up well enough and could presumably put one stump in front of the other. It probably wouldn’t be the easiest locomotion, and I imagine he couldn’t get very far very fast, but since he can stand he would, in some way or other, be able to walk. Second, although the scale in the image seems a bit wayward, it looks as though anybody, preferably (though not necessarily) somebody with feet, could get over that wall without too much trouble.

Mind you, I expect most alchemists are not great climbers; or walkers.

The above quotation and image are from a 1617 alchemical “emblem book” by Michael Maier (aka Michael Majerus) titled “Atalanta Fugiens, The Flying Atalanta or Philosophical Emblems of the Secrets of Nature.” It consists of 50 emblems (what we might call epigrams) each with an illustration (by Matthäus Merian) along with a discussion or discourse about the emblem, and then a related piece of music in the form of a fugue.

Alchemy isn’t exactly an open book to me, but that emblem above - “Emblema XXVII” - sounds fair enough. You need a key to alchemy, you need feet for walking. However a couple of observations emerge from looking at that image. First, the fellow there doesn’t seem to be much hindered by the lack of feet. He’s standing up well enough and could presumably put one stump in front of the other. It probably wouldn’t be the easiest locomotion, and I imagine he couldn’t get very far very fast, but since he can stand he would, in some way or other, be able to walk. Second, although the scale in the image seems a bit wayward, it looks as though anybody, preferably (though not necessarily) somebody with feet, could get over that wall without too much trouble.

Mind you, I expect most alchemists are not great climbers; or walkers.

Published on August 20, 2017 18:42

August 18, 2017

A CAUTIONARY TALE

Published on August 18, 2017 06:16

August 17, 2017

A CAUTIONARY TALE

Published on August 17, 2017 18:56

August 6, 2017

SAM'S WALKING WISDOM

"And having heard, or more probably read somewhere, in the days when I thought I would be well advised to educate myself, or amuse myself, or stupefy myself, or kill time, that when a man in a forest thinks he is going forward in a straight line, in reality he is going in a circle, I did my best to go in a circle, hoping in this way to go in a straight line. For I stopped being half-witted and became sly, whenever I took the trouble. And my head was a storehouse of useful knowledge. And if I did not go in a rigorously straight line, with my system of going in a circle, at least I did not go in a circle, and that was something. And by going on doing this, day after day, and night after night, I looked forward to getting out of the forest, some day." Molloy, Samuel Beckett

Published on August 06, 2017 11:50

August 2, 2017

OF WALKING AND WRAPPING

The days have been hot – pushing 90 degrees – and it’s been humid (that’s known as “monsoonal moisture” in these parts), but I’ve been walking because it’s what I do. And of course I’ve been doing it early-ish or late-ish in the day to avoid the worst of the heat, and I’ve been walking more or less in the neighborhood, although trying to head for those streets that, for one reason or another, I never usually walk down.

It must be a few years since I walked past the garden below, with its blue glass decorations. It’s right alongside the street, and most of those bottles and vases are just a stone’s throw away, and yet they remain intact. This seems a reason to be cheerful.

They’ve been trimming – pollarding, I suppose is the word - the trees in parts of the neighborhood – a huge operation, big trucks, a big crew, a big mess, especially when it comes to the ficus trees – a job that needs doing, and it doesn’t do the trees any harm, they'll be back just as big next year, but of course it does mean there are certain sidewalks where you can’t walk at all. And it must be said that the guys on the crew, while by no means hostile, didn’t look very cheerful: maybe it’s the heat, and maybe the one below just doesn’t like being photographed.

Now, I don’t know much about the school system in Los Angeles. Some people say it’s a disaster, some people send their kids to public schools (which means exactly the opposite in the States than it does in Britain) and they say they’re fine. Even so, this sign warning drivers that there’s a school nearby, may be a symbol that not everything is absolutely as it should be.

Of course you can’t (and shouldn’t) walk in LA without being aware of the traffic. Mostly it’s about avoidance, and yet my inner motorhead never quite gives up, and when I see a truck like this one, my heart does leap just a little.

And you know, I’m always fascinated by the wrapped cars of Los Angeles that I see when I’m walking. I know there are wrapped cars in plenty of other places but I’ve never seen so many as here, and I’m never sure whether it’s for protection from the sun or to dissuade low-lifes from running a screwdriver along your paintwork, not that one precludes the other. Sometimes it’s a full cover:

Sometimes just half:

But how about this one, gift-wrapped, padded, in disguise:

As you can probably work out, this is some some kind of forthcoming model from one of the big manufacturers, being secretly road-tested. Of course, a cynic might think that under the disguise there’s going to be some big, ugly, penis-substitute of a pickup truck, essentially no different from any of the other monsters on the roads. My inner motorhead can be pretty cynical.

And of course, the Los Angeles housing crisis rumbles on, and here’s one feller who’s found a temporary solution:

It looks like one of those “forts” that kids build in their grandparents’ back yards, although since the guy was passed out and there was “drug paraphernalia” visible on the mattress, the phrase “not in my back yard” sprang rather readily to mind.

Published on August 02, 2017 15:05

July 26, 2017

HUNKERING HOME

Mention of Hull brings us pretty much inevitably to Phillip Larkin. There’s the Larkin Trail in Hull these days, in three sections, only two of them easily walkable. The Website says, "To follow in Larkin's tracks is to take not only a literary journey, but also journeys through diverse landscapes and rich architecture and, seeing the city through a poet's eyes, to gain a philosophical view of the place where Larkin lived and worked for three decades."

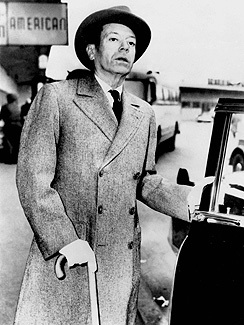

There’s also the above statue, by Martin Jennings, of Larkin in Hull station. It’s supposedly inspired by Larkin’s poem “The Whitsun Weddings” so I suppose he’s hurrying to leave Hull, which may or may not be significant.

Walking crops up fairly often in Larkin’s works, but it’s seldom, if ever, a joyous or uncomplicated subject for Larkin, but then what is? Generally it’s a marker for something much bigger that itself. This line from “New Year Poem” – “From roads where men go home I walk apart” – which somehow reminds of the line Sheldon Cooper says in The Big Bang Theory – “Like the proverbial cheese, I stand alone”

There’s this from “Poetry of Departure”So to hear it said

He walked out on the whole crowd

Leaves me flushed and stirred,

Like Then she undid her dress

Or Take that you bastard;

And there’s this from “Dockery and Son” which I suppose is, in part, a railway poem:I fell asleep, waking at the fumes

And furnace-glares of Sheffield, where I changed,

And ate an awful pie, and walked along

The platform to its end *And there’s this from a wonderfully gloomy letter from to his lover, Monica Jones, “I seem to walk on a transparent surface and see beneath me all the bones and wrecks and tentacles that will eventually claim me: in other words, old age, incapacity, loneliness, death of others & myself...”

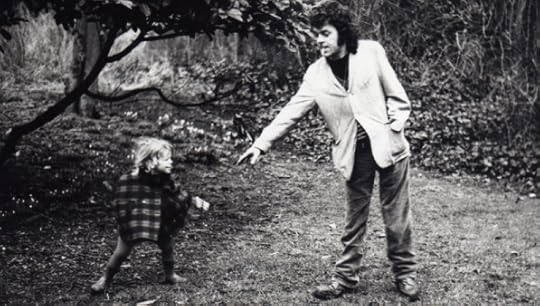

Larkin and Jones

Larkin and Jones

But for many in Hull, and possibly elsewhere as well, Larkin may be most famous for the poem “Toads.” The toad is initially the poet’s daily work which squats upon him but in the end he decides

… something sufficiently toad-like

Squats in me, too;

Its hunkers are heavy as hard luck,And cold as snow,

Now, hunker is an interesting word. It’s a synonym for the haunch, of course, so to hunker down is to squat on your haunches, which is in keeping with the sense of the poem. But, if online dictionaries are to be believed, hunkering is also a synonym for walking, as in: “Slang: to lumber along; walk or move slowly or aimlessly.”Was Larkin aware of this? Who knows? Poets are tricky people when it comes to the overtones and undertones of language.

Nor can we be absolutely sure how Larkin would have felt about the celebration in his name “Larkin with Toads, Hull’s largest ever public art project.” Originally set up in 2010 it was revived in 2015 and featured 40 extra large “artist-decorated” (how long have you got to pick the bones out of that one?) fiberglass toads positioned in and around the city.

They formed a “walking trail” of course.

There’s also the above statue, by Martin Jennings, of Larkin in Hull station. It’s supposedly inspired by Larkin’s poem “The Whitsun Weddings” so I suppose he’s hurrying to leave Hull, which may or may not be significant.

Walking crops up fairly often in Larkin’s works, but it’s seldom, if ever, a joyous or uncomplicated subject for Larkin, but then what is? Generally it’s a marker for something much bigger that itself. This line from “New Year Poem” – “From roads where men go home I walk apart” – which somehow reminds of the line Sheldon Cooper says in The Big Bang Theory – “Like the proverbial cheese, I stand alone”

There’s this from “Poetry of Departure”So to hear it said

He walked out on the whole crowd

Leaves me flushed and stirred,

Like Then she undid her dress

Or Take that you bastard;

And there’s this from “Dockery and Son” which I suppose is, in part, a railway poem:I fell asleep, waking at the fumes

And furnace-glares of Sheffield, where I changed,

And ate an awful pie, and walked along

The platform to its end *And there’s this from a wonderfully gloomy letter from to his lover, Monica Jones, “I seem to walk on a transparent surface and see beneath me all the bones and wrecks and tentacles that will eventually claim me: in other words, old age, incapacity, loneliness, death of others & myself...”

Larkin and Jones

Larkin and JonesBut for many in Hull, and possibly elsewhere as well, Larkin may be most famous for the poem “Toads.” The toad is initially the poet’s daily work which squats upon him but in the end he decides

… something sufficiently toad-like

Squats in me, too;

Its hunkers are heavy as hard luck,And cold as snow,

Now, hunker is an interesting word. It’s a synonym for the haunch, of course, so to hunker down is to squat on your haunches, which is in keeping with the sense of the poem. But, if online dictionaries are to be believed, hunkering is also a synonym for walking, as in: “Slang: to lumber along; walk or move slowly or aimlessly.”Was Larkin aware of this? Who knows? Poets are tricky people when it comes to the overtones and undertones of language.

Nor can we be absolutely sure how Larkin would have felt about the celebration in his name “Larkin with Toads, Hull’s largest ever public art project.” Originally set up in 2010 it was revived in 2015 and featured 40 extra large “artist-decorated” (how long have you got to pick the bones out of that one?) fiberglass toads positioned in and around the city.

They formed a “walking trail” of course.

Published on July 26, 2017 17:04

July 20, 2017

TOWARDS THE DOOR WE NEVER OPENED

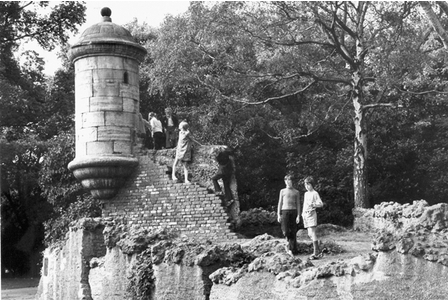

Since I’ve been thinking about walking in gardens, I inevitably thought about walking in parks, which inevitably meant I returned to Travis Elborough’s book A Walk in the Park – now out in paperback - and I find this passage:“There are few sights in England that can quite equal the absurd charm of the imitation Khyber Pass in Hull’s East Park. This slice of South Asia in the East Riding sits just a short stroll away from an animal house that is home to alpacas from Peru and a lake where oversized swan pedalo boats bob about. The park was planned and opened to honour Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee in 1887 and the pass was dreamed up by its supervisor Edward Peak and fashioned in artificial rock and material foraged from the Hull Citadel, an old fort that had once defended the town’s port.”

Now it so happens that I know a couple of people with Hull connections and they were familiar with East Park, and had even been walking there, but perhaps inevitably they’d never heard of this Khyber Pass replica, despite the presence in the park of this informative sign:

I think you’d have to say that as replicas go it’s not the most faithful recreation you’ve ever seen, especially since it involved the copy of an Arab doorway from Zanzibar, which doesn't seem to have a whole lot to do with the Khyber Pass.

The actual Khyber Pass looked like this back then,

And it looks like this now:

And I began to wonder how easy it would be to walk through dislocated or simulated geographical features of the world. The boundary wall of Piccadilly Gardens in Manchester has been in the news lately - a Brutalist bit of concrete that locals refer to as the Berlin Wall. It doesn’t look so bad to me but it’s apparently “much hated” by locals, and the news is that there are now plans to demolish it.

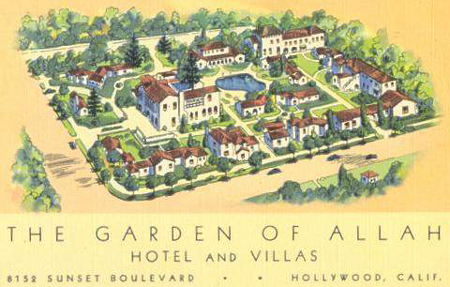

There used to be the Garden of Allah here in Los Angeles, though not a garden at all, but a hotel on Sunset Boulevard run by one Alla Nazimova (real name Adelaida Yakovlevna Leventon), and occasional home to the likes of Errol Flynn, Dorothy Parker, Scott Fitzgerald et al. It was demolished in 1959, but a replica has been being built at Universal Studios, Florida, and is used as a media center.

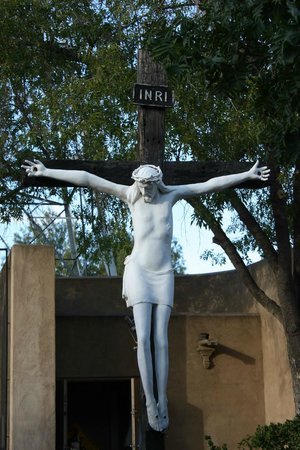

There is also the Garden of Gethsemane in Tucson, which contains sculptures of the Last Supper and the Crucifixion which (unless by biblical knowledge is even sketchier than I think it is) did not take place in said garden.

The “real” Garden of Gethsemane in Jerusalem (its original location is disputed, so this may itself be a replica) looks like this:

There’s also London Bridge in Havasu City, Arizona, which Mr. Elborough has written about at length, but that’s a transplant of the thing itself, not a replica. The Shoreline walking trail will take you right under it, through Rotary Park.

So I emailed young Elborough and asked him if he thought there was any meaningful distinction to be drawn between what constitutes a park and what constitutes a garden. He offered this, “I think more generally public gardens tended be bequests of existing private gardens - though not always - and usually smaller and horticultural, lacking sports fields etc. but god knows!” That’s good enough for me, for now.

Published on July 20, 2017 13:15

July 19, 2017

YOU'RE THE TOP

Does anybody not love the songs of Cole Porter? Well, some no doubt, but not many, surely. “Let’s Do It,” “I Get A Kick Out Of You,” “Love For Sale,” “You’re the Top,” “Did you Evah,” to name just a few that I happen particularly to love.

Porter even mentioned walking once in a while, perhaps most famously in these lines:“The night is young, the skies are clear So if you want to go walking, dear, It's delightful, it's delicious, it's de-lovely.”

That, of course, is from “De-lovely” – a word and a title that’s always rubbed me up the wrong way. Porter’s use of language is generally so great, but here it seems a bit twee, if you ask me, and yet also (damn in) incredibly memorable.In a different song Porter wrote, “I’d walk a mile for that schoolgirl complexion, Palmolive does it every time.”

That’s from “It Pays to Advertise.” And in “When my Baby Comes To Town” you’ll find this:“Yes, daily she takes a walkAnd you should see those natives gawk”

And yes, Porter understood that New York was a walking city, this from “Longing for Dear Old Broadway”“I’d love to walkStart for New YorkBack where the lobsters thrive.”

Porter himself was quite a walker for the first part of his life. From his time at Yale onwards he’d regularly go off on walking vacations, and as he became rich and famous, his companions were rich and famous too. One of them, Moss Hart, describes Porter as “an indefatigable sightseer, a tourist to end all tourists. Everything held an interest for him. No ruin was too small not to be seen, particularly if it meant a long climb up a steep hill.”

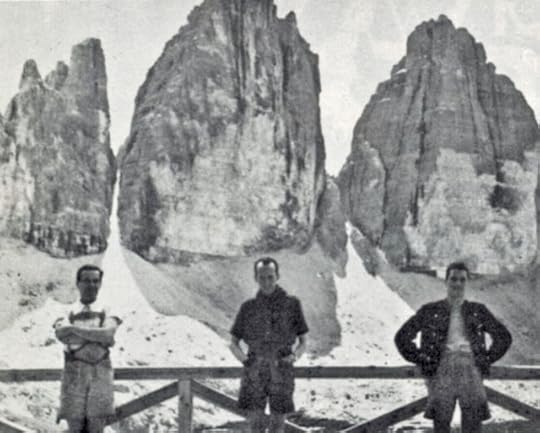

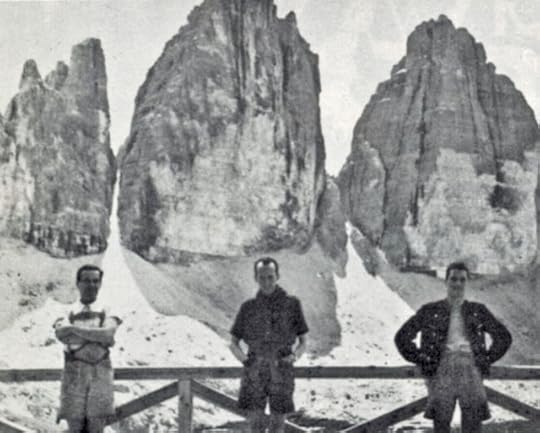

Things changed dramatically in 1937. Porter had recently returned to New York after a walking vacation in Europe (the picture above is from that trip and shows Porter with Howard Sturges and Ed Tauch). Porter was spending time upstate, and riding a horse, which stumbled and fell on him, crushing both his legs; forever changing, and by many lights ruining, his life.The doctors recommended amputating his right leg, and possibly the left as well, but Porter, supported by his wife (recently estranged, now reconciled) and his mother, refused, and after a seven month stay in hospital he returned to some semblance of his old life, which included what many of us would still think was an awful lot of traveling.

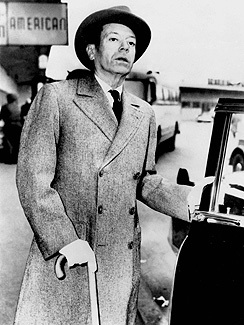

It’s hard to say whether Porter was altogether right to refuse amputation. He could still walk but only with difficulty, using a cane and a leg brace, and over the next twenty years he had 30 agonizing operations on his legs. One of these involved breaking femurs again and resetting them. Along the way he gave names to his legs, women’s names it might be noted: Josephine was the left leg, just about tolerable; Geraldine was the right — “a hellion, a bitch, a psychopath.”

For all his resistance, Geraldine nevertheless had to be amputated in 1958. Porter was devastated, said he felt like “half a man” and never wrote another song. There was some serious self-medication with alcohol and narcotics, which created problems of their own, and he made a fairly nasty end. He was given a false leg and struggled to use it, though there were times when he had to be carried around by his valet. Porter died of kidney failure on October 15, 1964, in St John’s Hospital, Santa Monica.

I once went to a talk given by Ian Dury – he of “Reasons to be Cheerful” – and this was after he’d been diagnosed with terminal cancer. Quite apart from that, he was a man who had his own problems with walking, as a result of childhood polio.

Dury expressed some surprise that Porter, of whom I think he was a fan) had continued to write cheerful, optimistic, upbeat songs even after his accident. Dury thought the accident and the pain would have moved Porter to write melancholy songs of pain and loss.

I’d have thought Dury’s own experience would have taught him that creativity doesn’t necessarily work that way. I can’t find much about walking in Dury’s work, though there is the Dury’s song “Spasticus (Autisticus),” an anti-pity-for-the-disabled song, which was banned by the BBC, in the days when the BBC cared about such things. The relevant couplet runs,

“I'm knobbled on the cobblesCos I hobble when I wobble”

That’s not exactly Cole Porter-style word play (you can’t help thinking hobble and wobble should be reversed, but that’s the way they appear on the single, and the way Dury sings them on the one live YouTube version I’ve found) but it ain’t at all bad.

Porter even mentioned walking once in a while, perhaps most famously in these lines:“The night is young, the skies are clear So if you want to go walking, dear, It's delightful, it's delicious, it's de-lovely.”

That, of course, is from “De-lovely” – a word and a title that’s always rubbed me up the wrong way. Porter’s use of language is generally so great, but here it seems a bit twee, if you ask me, and yet also (damn in) incredibly memorable.In a different song Porter wrote, “I’d walk a mile for that schoolgirl complexion, Palmolive does it every time.”

That’s from “It Pays to Advertise.” And in “When my Baby Comes To Town” you’ll find this:“Yes, daily she takes a walkAnd you should see those natives gawk”

And yes, Porter understood that New York was a walking city, this from “Longing for Dear Old Broadway”“I’d love to walkStart for New YorkBack where the lobsters thrive.”

Porter himself was quite a walker for the first part of his life. From his time at Yale onwards he’d regularly go off on walking vacations, and as he became rich and famous, his companions were rich and famous too. One of them, Moss Hart, describes Porter as “an indefatigable sightseer, a tourist to end all tourists. Everything held an interest for him. No ruin was too small not to be seen, particularly if it meant a long climb up a steep hill.”

Things changed dramatically in 1937. Porter had recently returned to New York after a walking vacation in Europe (the picture above is from that trip and shows Porter with Howard Sturges and Ed Tauch). Porter was spending time upstate, and riding a horse, which stumbled and fell on him, crushing both his legs; forever changing, and by many lights ruining, his life.The doctors recommended amputating his right leg, and possibly the left as well, but Porter, supported by his wife (recently estranged, now reconciled) and his mother, refused, and after a seven month stay in hospital he returned to some semblance of his old life, which included what many of us would still think was an awful lot of traveling.

It’s hard to say whether Porter was altogether right to refuse amputation. He could still walk but only with difficulty, using a cane and a leg brace, and over the next twenty years he had 30 agonizing operations on his legs. One of these involved breaking femurs again and resetting them. Along the way he gave names to his legs, women’s names it might be noted: Josephine was the left leg, just about tolerable; Geraldine was the right — “a hellion, a bitch, a psychopath.”

For all his resistance, Geraldine nevertheless had to be amputated in 1958. Porter was devastated, said he felt like “half a man” and never wrote another song. There was some serious self-medication with alcohol and narcotics, which created problems of their own, and he made a fairly nasty end. He was given a false leg and struggled to use it, though there were times when he had to be carried around by his valet. Porter died of kidney failure on October 15, 1964, in St John’s Hospital, Santa Monica.

I once went to a talk given by Ian Dury – he of “Reasons to be Cheerful” – and this was after he’d been diagnosed with terminal cancer. Quite apart from that, he was a man who had his own problems with walking, as a result of childhood polio.

Dury expressed some surprise that Porter, of whom I think he was a fan) had continued to write cheerful, optimistic, upbeat songs even after his accident. Dury thought the accident and the pain would have moved Porter to write melancholy songs of pain and loss.

I’d have thought Dury’s own experience would have taught him that creativity doesn’t necessarily work that way. I can’t find much about walking in Dury’s work, though there is the Dury’s song “Spasticus (Autisticus),” an anti-pity-for-the-disabled song, which was banned by the BBC, in the days when the BBC cared about such things. The relevant couplet runs,

“I'm knobbled on the cobblesCos I hobble when I wobble”

That’s not exactly Cole Porter-style word play (you can’t help thinking hobble and wobble should be reversed, but that’s the way they appear on the single, and the way Dury sings them on the one live YouTube version I’ve found) but it ain’t at all bad.

Published on July 19, 2017 15:43

July 15, 2017

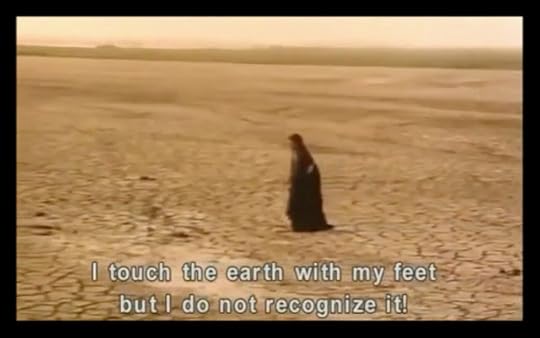

BENEATH THE DESERT, THE STREET

Published on July 15, 2017 14:25

Geoff Nicholson's Blog

- Geoff Nicholson's profile

- 55 followers

Geoff Nicholson isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.