Joshua Corey's Blog, page 17

April 28, 2015

Baroque Nation

Poetry is nation-building by other means, a shadow government that arises wherever a people is denied access to its own institutions, cut off from its own powers, its very language de-authorized. Yeats and his compatriots in Ireland before (and perhaps even more crucially, after) independence; Akhmatova in the Soviet Union quietly defying Stalin; the vast and complex tradition of poetry and anti-poetry in Latin America that has led to the murder and disappearance of poets who dared to represent the people against the power of the state. In this country poetry on the page hasn't often played this role, but rap and spoken word has. Chuck D called rap "CNN for black people" and an album like Kendrick Lamar's To Pimp a Butterfly lives up beautifully and painfully to this charge. Look at the cover, in which one of the most marginal and vulnerable groups in America--young black men--have taken over the White House lawn with fistfuls of Franklins, while a John Roberts-type lies cartoonishly KO'ed in the foreground and the White House--whose black occupant just owned his "anger translator" in front of the largely white audience that can't or won't hear that anger, that reduces the burning of Baltimore to the action of "thugs" and not the predictable response to the slow violence that has been grinding Baltimore's poor black population down for the past fifty years.

The album itself is angrily, emphatically, gloriously baroque: excessive, combinatory, enfolding layer upon layer of black musical history in every groove, talking back to it, culminating in a quasi-imaginary interview between Lamar and his hero Tupac. And it meats the Yeatsian standard for poetry: "We make out of the quarrel with others, rhetoric, but of the quarrel with ourselves, poetry." Lamar's album has hit me hard, as few albums do, because of that dialogic, self-confronting quality that I associate with the strongest lyric poetry, going back at least as far as the English Metaphysicals--that is to say, poets of the Baroque period as it expressed itself in England: Herbert, Marvell, Donne. It rewards re-listening. I'm listening to it right now.

The Baroque is in the air. Eight years ago I wrote a little essay called "Notes Toward the Postmodern Baroque" in which I explored the Baroque's art-historical origins as a kind of propaganda effort of the Counter-Reformation that, by its excess, tends to subvert the very ideology that sponsors it, the ideology that the art is supposed to legitimate. I go on to say that, now that the legitimation function has been detached from poetry, we have gone beyond a Habermasian "legitimation crisis" into a crisis of legitimation itself. Here's the central paragraph:

Today we are living through another legitimation crisis, or to speak more accurately, a crisis of legitimation. The right-wing reaction to the liberation movements of the 1960s has pulsed like a shockwave through our society, opening an unprecedented rift between politics and culture that continues to widen. As Andrew Joron has remarked, “Here in America... ‘culture’ has been reduced to a simple play of intensities, to the simultaneously brutal and sentimental pulsions of mass media. Any ‘legitimation function’ would be superfluous: the American machine, with its proudly exposed components of Accumulation and Repression, has no need for such a carapace” (Fathom 18). Increasingly, it seems that the forces of capitalism no longer even need the carapace of politics, let alone culture. For confirmation of this we need only glance at the Riefenstahlian spectacle of George W. Bush’s famous “Mission Accomplished” speech, which the speed of events transformed almost overnight into a dialectical image of the man’s hubris and haplessness. And yet the war machine marches on unfazed, sustained as it is by a subtly self-distributed myth of accumulation and enclosure that retains all the mystification of myth while discarding its traditional forms.

Look at that album cover again: a "riot" or should I say a mattering of black male bodies (#BlackLivesMatter) almost obscuring the symbol of legitimate democratic government, a symbol (and a government) that has been badly undermined by relentless racist opposition to its lawfully elected occupant, Barack Obama. It's a dialectical image, representing the greatest fears of white supremacists but also calling into question the adequacy of our existing institutions when confronted with the structural violence and rapacity of our society. Can poetry--written poetry, poetry on the page--ever top this? Should it even try?

Last year, Steve Burt wrote a review-essay in Boston Review called "Nearly Baroque," which was then critiqued by various posters on the Montevidayo blog, partly for its provincialism (Lucas de Lima takes Burt to task for participating in "the dislocating flows of neoliberal global capital and its digitalized erosion of nationhood and national literature") and partly for his vaguely Protestant emphasis on the values of rigor and restraint (Johannes Göransson asks bluntly, "Is the 'Baroque' Tasteless?"). The constellation of neo-Baroque poets invoked by the Montevidayans is certainly more diverse and cosmopolitan than the American-only list of poets that Burt treats in his essay, and I think they are also right to question how Burt's "nearly baroque" evades the role of kitsch and camp in this poetry. But I do love how he applies the label "femme" to this poetry in remarking its ornamental qualities, its celebration of artifice, and some of the poets he mentions, especially Geoffrey Nutter and Robyn Schiff, are among my favorites working today. Probably the last paragraph of his piece is most relevant to what I'm trying to feel out here, and I'm going to go ahead and quote it:

I have been trying to recommend these poets: I admire them very much. Yet I have also been laying out, almost despite myself, a way to read them skeptically, as symptoms of a literary culture that has lasted too long, stayed too late. Engagé readers might say that the nearly Baroque celebrates, and invites us to critique, a kind of last-gasp, absurdist humanism. We value what has no immediate use in order to avoid becoming machine parts, or illustrations for radical arguments, or pawns for something larger, whether it is existing institutions or a notional revolution. And we must keep moving, keep making discoveries, as the scenes and lines and similes of the nearly Baroque poem keep moving, because if we stop we will see how bad—how intellectually untenable, how selfish, or how pointless—our position really is. The same suspicious readers might say that these nearly Baroque poems bring to the surface questions about all elite or non-commercial or extravagant art: Is it a waste? What does it waste? Can it ever get away from the violence required, if not to produce it, then to produce the society—yours and mine—prepared to enjoy it? The rococo is the art of an ancien régime: it may be that the nearly Baroque poetry of our own day calls our regime ancien as well. It does not pretend to predict what could replace it.

Burt's argument for--and here, against--the "nearly Baroque" or "almost rococo" hinges on a conception of this elaborate and ornamental poetry as a conquest of the useless that paradoxically evades poetry's uselessness, or any notions of the useful, so we won't discover "how bad... our position really is." I'm not sure that's an adequate description of either Schiff's or Nutter's poetry: Schiff is not only formally inventive but concerned with the deep histories of objects in an at-least Benjaminian way, while the elegiac qualities of the Nutter poem that Burt quotes, "Purple Martin," are to my ear sharply and self-accusingly ironic, and smartly engaged with both the liberatory and fascist dimensions of Heidegger's philosophy.

But this may matter less than Burt's incisive question about "the violence required, if not to produce [this poetry], then to produce the society--yours and mine--prepared to enjoy it?" There is, first of all, a kind of violence done in postmodern Baroque poetry (I prefer this term, as hackneyed as it is, to Burt's overcute coinages "nearly Baroque" or "Baroque Baroque"), directed at the anti-eloquent plain speaking English that dogs and cats can read that in its hegemony over our culture wipes out nuance, difference, and the sites in which either historical memory or the genuinely new are most likely to emerge. That violence can be directed inside the poem, at the lyric self itself, as in the work of Finnish poet Tytti Heikkinen that Burt discusses in a more recent review-essay, "Poems About Poems," or in the work of poets associated with the Gurlesque--the violent femmes of the postmodern Baroque. It might also be a prophylactic violence, the both-ways violence Burt describes in the same essay when discussing Daniel Borzutzky's The Book of Interfering Bodies. But more disturbing is the implication that our enjoyment of the postmodern Baroque is an enjoyment of the very structural violence that this poetry seeks to take refuge from. The unappetizing alternatives appear to be a Baroque that renders violence spectacular and consumable (Caravaggio-style) or a Baroque conditioned by the violence it conceals and evades.

Discussing Borzutzky's work Burt soberly remarks that "We may want poetry to do what it cannot do, to perform a magic in which we no longer believe or a political efficacy that no longer makes sense," before going on to remark that in his poems, "we are brought up short and discover that poetry is the despised Other of more consequential textual forms such as the PowerPoint slideshow." More consequential, not more legitimate--PowerPoint is the language of power (I am reminded of articles in the New York Times a few years back about how the limitations of PowerPoint as a medium may have led to some of the costlier decisions made by the American military--I imagine each and every proposed drone strike is PowerPointed, so as to pre-empt every consideration of what might otherwise escape such euphemisms as "civilian casualties"). It seems to me that culture is not, in the end, separable from its legitimation function--for how else except through culture do we come to recognize or critique our own values?--and the crisis is indeed centered on the assumption that our institutions can somehow run on autopilot, no matter how obstructed (on the legislative level), or detached from everyday life (as in the farce of our presidential politics, parodied by non-events like Hillary Clinton's Chipotle visit), or deeply structured by repression (how can we "reform" the police when their actions merely express the consequences of the white majority's refusal to recognize the humanity of dark-skinned people?).

In its excesses the postmodern Baroque can theatricalize poetry's abjection, and help us to recognize our own abjection--as citizens, as marginalized bodies. It can also, in spite of everything, make a place for beauty--not a resigned, detached, or decadent beauty but a complex beauty that never says or celebrates anything without putting that thing, and the self's relation to it, into question. It is the other of power, but not of politics, because politics happens when people organize--on any level, including the level of language--and direct that organization--call it Blake's organized innocence--against the hollowness of power. If revealing the nakedness of the emperor does not, in this historical moment, diminish one whit the emperor's control of the war machine--and that is a terrifying and deeply uncomfortable truth--it is nevertheless necessary to the imagination of alternatives. Including, most simply and radically, the imagination of alternative relations to our own selves, as more complex, more thoughtful, more diverse, more perverse, more impoverished, and more capable of forging connections than we might otherwise ever have realized.

A much-bandied quote of the moment is Martin Luther King Jr.'s "A riot is the language of the unheard." We condemn riots for their violence, especially their violence to property, and yet a riot--or an uprising--has the potential, the barest potential to be heard (as opposed to processed as spectacle, which is what the mainstream networks have been busily doing, putting the riot's historical rootedness on mute). And that capacity to be heard is rooted in excess, in moments of beauty as in the image above, as well as in the more distasteful and horrifying moments that are inseparable from the beauty. The postmodern Baroque, in poetry and out of it, has the capacity for making these connections, rendering them legible, if not legitimate.

March 12, 2015

Infinitive

by Giacomo Leopardi

This hill has always been precious to me

and this hedge, that cuts off and conceals

from me the finality of horizons.

But as I sit and stare, boundless

spaces beyond that and superhuman

silences, and deepest quiet

counterfeits my thought, where for a bit

the heart is overwhelmed. I hear

wind rustling through these trees and compare

infinite silence to its voice. So

I'm reminded of the imperishable, and the dead seasons,

and the present, and the life of sound.

So in immensity my thought is drowned

and shipwreck is sweet in such a sea.

*

Sempre caro mi fu quest'ermo colle,

E questa siepe, che da tanta parte

Dell'ultimo orizzonte il guardo esclude.

Ma sedendo e mirando, interminati

Spazi di là quella, e sovrumani

Silenzi, e profondissima quiete

Io nel pensier mi fingo; ove per poco

Il cor non si spaura. E come il vento

Odo stormir tra queste piante, io quello

Infinito silenzio a questa voce

Vo comparando: e mi sovvien l'eterno,

E le morte stagioni, e la presente

E viva, e il suon di lei. Così tra questa

Immensità s'annega il pensier mio:

E il naufragar m'è dolce in questo mare.

December 24, 2014

Transparent

So we're watching the much-lauded Amazon Streaming show Transparent and we've hit the flashback episode and debating whether the show has jumped the shark. After all, in spite of clever writing and astonishingly subtle and empathetic performances by the cast (chiefly of course Jeffrey Tambor, who secured national treasure status back in the days of The Larry Sanders Show and now approaches deityhood), the show was already testing my tolerance for the clueless misbehavior of extraordinarily entitled well-heeled white Angelenos who lack the last name of Bluth. What is going on with Ali, anyway, as she watches her thirteen year-old self flirt dangerously with a grown man, or maybe it's the other way around? Then I find myself saying out loud, "The weirder it gets, the better it gets." And then I'm listening to the echo.

Inadvertently, while binge-watching an example of what everyone too strenuously agrees to be the dominant art form of our time, I have stumbled across an aesthetic truth, or my truth of the aesthetic. Weirdness, strangeness, risking the alienation of audiences: only by trangressing whatever it is you have to transgress can one deliver genuinely valuable, genuinely powerful shocks of recognition. And recognition is the name of the game--something akin to, yet far from, the authenticity that older models of art hold up as the supreme value (something Transparent, with its sometimes sly, sometimes dopey challenges to gender normativity, is delighted to discard. And let me take advantage of this parenthetical to note that the show's depictions of academia--from the wealth of Mort/Maura's retired political science prof to the broad and unfunny satire of a women's studies classroom--is the weakest dimension of this show, precisely because it deprives this viewer, at any rate, of that salutary shock.)

We're long past shock value for its own sake, I hope--shock in that old-school epater-les-bourgeois Johnny-Rotten-spitting-on-the-audience sort of way. Shock meant to transmit one's alienation, or ressentiment, to the class of straights or parents or flatlanders, well that's just the desire for recognition turned on its head. I'm talking about the classical shock, the sublime comedy of the separated and reunited twins of Twelfth Night or the miraculous rescue from tragedy at the end of The Winter's Tale when Leontes, who's very far from deserving it, has the wife he harrowed to death out of jealousy restored to him. I'm talking about the uncanny, encountering the self in the other, but without reducing the other's otherness--if anything, increasing it. The other is inside, unassimilable.

Ali, the lost daughter of Transparent played brilliantly and unreservedly by Gaby Hoffmann, keeps looking into the mirrors of her best friend, her brother, her father, her lovers, and her younger self, and what she sees shocks and disturbs her every time and moves her closer, maybe, to action--to what her father calls "landing." Being a woman--or a man--is not an identity, if by "identity" we mean something stable and same-same. Womanliness and manliness are means, not ends. Though to be an artist--to have a certain kind of relation to the self--always means to have passionate feeling for one's materials.

The root material for any artist being of course one's own body, one's constantly mutating, translating, betraying body, with its frighteningly permeable boundaries, never entirely separable from the room or town or landscape or gene pool or pollution or--most dizzying of all--the stream of time it finds itself in. The single greatest challenge being to live in the body, on its own terms. Reckoning with desire, deformity, death. Farewell to the ideal unreflectively reflecting back at us from every too-smooth surface.

I go to the gym and larger-than-life images of fit people under thirty look out at me. I look around at the people actually using the equipment and I see men and women of all ages, some packed with muscle but most of them ordinary, even frail, pushing against the weight of their own bodies, spending time with those bodies, hoping to slow the process of decay. Why can't they see themselves? Why did I spend so much of my life comparing myself to the men I'd never be like?

Writing is eccentric or else it's just another stitch in the predetermined hallucination. I spent my twenties and thirties seeking the approval of elders; now in my forties it's no longer satisfying to submit the products of my imagination to whatever other. I must first of all shock myself with what I do, to make it worth doing. To be somehow of service. How many times have I found myself, from a previously unimaginable angle, in books? In characters but more often in voices, in certain slants of language. How often have I, flatlined and flailing, been resuscitated by the cardiac rhythm of someone else's sentences? And the stranger they were, the more unfamiliar, the more sustaining the shock they administered. It seemed I breathed anew.

The strangest things I've written in the past few years involve a kind of cross-dressing. There's "Mrs. God" and a newer poem, "St. Joan," populated by sex-switching protagonists. My novel features a female protagonist, Ruth, and much of it is written from her point of view, though there are male points of view as well. A poem from The Barons, "It's Its," includes these lines: "A woman / in me lodged is my Ecclesiastes. For / there is, never, any, 'they.'"

The woman in me lodged is my mother, or so I've always thought. But what if it's, simply, me? I don't have, I don't think, any desire to cross dress "in real life," but there's no question that my imagination seems to come alive in a kind of ambisexuality. That I feel the shock of recognition when I read Jane Austen, Henry James, and Virginia Woolf. A sense that it's the woman in me lodged who can "feel it all."

Maybe all this is simply how the vocation to write can feel for a boy, this boy.

Écriture, literally "writing," more closely, the inscription of the body and difference in language and text. This body, this difference.

The pun of the title Transparent is pretty dumb: Morty/Maura is a trans parent, get it? But the show's uncanniness, which is the root of its success, which for me comes close to the roots of success for art in general, is that in showing us a thing, a thing that mirrors, the self-image gradually fades out into something rich and strange. Maybe that's why art, books, can feel like company. We cozy up to our own multitudes. But it's crucial, I think, that this new intimacy not cross over into appropriation. The other stays other. Whitman did not become the wounded soldiers he cared for; he cared for them. Watched with them. Bought them ice cream in heroic quantities. Wrote letters for them. And became, a little more, himself.

December 12, 2014

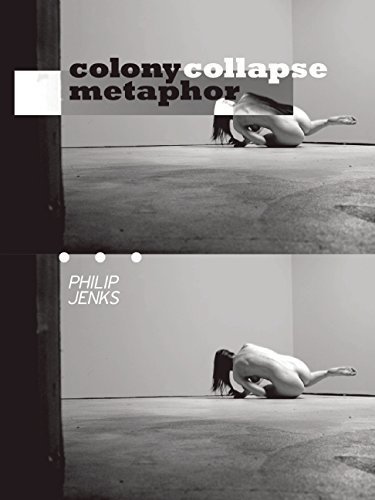

Colony Collapse Metaphor / Philip Jenks

Colony Collapse Metaphor

By Philip Jenks

When intensely felt historical experience intersects with language under extreme pressure, you might wind up with something like the poetry of Philip Jenks, which to my mind represents a kind of Appalachian écriture, the inscription of political, social, economic, and sexual difference onto and inside of the lyric. The title suggests the ongoing apocalypse that has penetrated to the fingers-ends of our culture, while also insisting--hopefully?--on its status as metaphor, a means of bringing the otherwise unsayable into contact with a reader's experience. The downright oddness, the gleeful perversity of Jenks's saying, keeps it local, keeps it, I dare to say, accessible. A shorter poem:

Irascible Tenant

seroquel, ardent neural raid.

irascible tenant,

"you are incorrigible, simply incorrigible."

reflections of a dying paper route.

or was it boy. that was my intention

when he was bested at the helm,

when he was blankets by daylight

and mouthing sections of biblic'

portion, oozing at mandible.

Take a certain someone, add gun

and some radiation. "treat street."

the Hatchers had one under couch

for special haunts. He grips dripping

without days without number, just

characteristics denoted

without sail, without border, dead

time circling, circling (ah) del'very!

The poem hovers between storytelling ("reflections of a dying paper route") and metaphor so extravagant it almost ceases to be metaphor ("mouthing sections of biblic' / portion, oozing at mandible"), in this case evocative of Kafka's Metamorphosis, so as to capture the essential loneliness of the poem's two figures, the boy and the titular armed and irascible tenant, perpetually "circling" one another as the boy's failed attempt to deliver the newspaper results in "del'very," a neologism that encompasses religious deliverance, delving into the depths, and devilry. These maneuvers are entirely typical of the book's antic, anguished energy, and yet no two poems are much alike, particularly given the breadth of subject matter, which ranges from medico-theological parables ("you cannot leave the subject blank") to the ravages of history as it gets (mis)taught ("Seventh"), to homages and addresses to the likes of Hart Crane and Neil Young, to a tour-de-force and timely examination of state-sponsored violence ("Eichmann thanks Madeleine"), to what reads as autobiography ("Morgantown, West Virginia").

Jenks's intellectual and poetic touchstones are varied, but I find myself especially drawn to the almost Benjaminian mixture of politics and theology. The book's dedication thanks a number of rabbis, and the beautiful elegy "Mysterium Tremendum" is dedicated in particular to a Rabbi Berger of Beth El Synagogue in Durham, North Carolina. According to his Poetry Foundation biography, Jenks is the son of an Episcopalian minister, and perhaps that's what put him in possession of something quite rare: a restless religious imagination at once skeptical and speculative in its consideration of the varieties of religious experience. I am reminded a little of the work of his friend Peter O'Leary and how his unabashedly mystical Catholicism insistently anchors itself to the things of this world, particularly the natural world, as in O'Leary's magnificent Phosphoresence of Thought. Jenks's work is grittier, performative in a different register. Here's an excerpt from (what a title) "Kill You Power Plant, Begins at Acts 2:1-13":

Gritty Decker's Creek overpass that Mistah Bee jumped from

exiled on his bicycle. I would skip a thousand kickball

Games for one phrase of his mad beautiful Black Jesus sentence

That trailed off the bridgely artifice

Spright and buggy, smeary glasses, his old school bike

Punctuated by the now bloody brown crik.

Before the time of the screen or even built bridge,

Bonehead crept across the lower beam, "protect nature."

The collage of registers here is unsurprising, even normative for a postmodern poem, but it's beautifully executed: look how each line maintains its integrity, the better to rub sparks against its closely cadenced neighbors: "Games for one phrase of his mad beautiful Black Jesus sentence / That trailed off the bridgely artifice / Spright and buggy..." But unlike so many postmodern collages there's nothing weightless here: the monads of lived local experience, of closely heard speech, slam into our "time of the screen" and, maybe, shatter it. It's rare for any poet--I will go on a limb here and say, any white poet--to combine the demotic and intellectual registers so effectively.

Back in 2002, Ben Friedlander published an essay about Jenks's first book, On the Cave You Live In (Flood Editions), titled "Philip Jenks and the Poetry of Experience" in Chicago Review. It was and is a provocative piece of criticism, using Jenks's work to argue a distinction between poetry as "a treasury of memorable statements" and poetry as "a particular experience we have of language." In some ways this is just a restatement of the old cooked-raw distinction, or of Charles Altieri's more magisterial distinction between "symbolist" and "immanentist" poetics, which in turn owes a debt to Schiller's dialectic of the naive and sentimental, Nietzsche's Apollo-Dionysus, and Jung's extravert/introvert. It all goes back to Wordsworth, for whom "poetic creation is conceived more as the discovery and disclosure of numinous relationships within nature that as the creation of containing and structuring forms" (Enlarging the Temple 17).

A poetic like Jenks's points, maybe, toward the discovery and disclosure of relationships within nature-culture, that hybridic zone in which we are all object-subjects and subject-objects, as conditioned by the "containing and structuring forms" that we create as by the rawer dimensions of creation that we struggle to structure and contain. It's a struggle that happens in and with language, a struggle that signifies aliveness, against the innumerable forces that conspire to confine us to the deadness of consumer choices disguised as freedom.

This is the first in what I hope will be a series of occasional reviews of books (mostly poetry but not exclusively so), by Chicago-area authors whose work is in my view underseen and undervalued. If you or someone you know is the author of such a work, let me know.

September 22, 2014

Walking Elegy

Brilliant chilled Monday

Curving down the Purple Line to French class

Il y a le Hancock Building

Il y a les arbes avec leurs feuilles vertes et rouges

Reading Walking Theory thinking air and light

So like San Francisco if light were elevation

Climbing sun towers glass a massive body of water

Feeling the edge of things land's end or muddy middle

Why I like this train is in the S's it describes

The black man in the pinstripe suit who is also reading poetry

The middle-aged white men in glasses looking at notebooks or screens or the window

The woman with tight curly hair bent listening to her red phone

The way we pass impossibly close to the bricked edges of buildings

I decide to get off at Merchandise Mart and wander out through the food court

Following an Exit sign through a succession of blank white doors

Industrial stairway down and a last door bearing a label

THIS DOOR IS UNLOCKED so we take for granted small freedoms

Then down another blind corridor to double doors also unlocked

And into the blinding sunshine slip on my shades and go look at the river

In time to see the architecture tour boat paddling past

Then following the river eastward under the heavy Argos-eyed Mart

Passing the heads of capitalists arranged on pylons like pikes

AARON MONTGOMERY WARD 1844-1913

EDWARD A. FILENE 1860-1937

GEORGE HUNTINGTON HARTFORD 1833-1917

(George with his pointed beard looks a little like Lenin seen from below)

JOHN WANAMAKER 1838-1922

THE MERCHANDISE MART HALL OF FAME

MARSHALL FIELD 1834-1906

(Marshall has a stiff mustache and wings combed into his hair)

FRANK WINFIELD WOOLWORTH 1852-1919

JULIUS ROSENWALD 1862-1932

GENERAL ROBERT E. WOOD 1879-1969

One thing we can say for sure of these men is they aren't alive

Train thundering stately now over the Wells Street Bridge

Let's pause and study the water skinned with floating trash

A plastic bottle with cleaner water in it bobs drunkenly just at the surface

Green Starbucks straws, potato chip bag, sticks and what looks like a frisbee

Another tourist boat passes its vision calibrated upward

Is what I write here predictable calculable from the influences of my past

Am I predetermined to see through soft Marxism that demonumentalizes my city

Vaguely tropical floral arrangements studding the bridge lurid dark pinks and oranges

May be a trick of my sunglasses which shade everything gray and green

I am not too interested in the history but I do enjoy walking across bridges

One thing this Chicago is in this moment is scarcely populous

There's a panhandler crouched on the south end with scarcely any passersby to panhandle

A very small person in sunglasses could be of any sex

I don't have any change I say to myself and linger with small irony

In and out of cold shade more people a firetruck wails across Clark Street

Closer to Marina City a place the Jetsons might have lived

Maybe they will someday weren't they from our future?

M

O

R

T

O

N

S

T

H

E

S

T

E

A

K

H

O

U

S

E

H

O

T

E

L

M

O

N

A

C

O

People on their smoke breaks in a kind of terraced garden

Overviewing a gravel barge and an angled crane pointing to "55"

Black-eyed Susans eye me and these little violet cups

Even smaller I think that's heather a profusion of tiny trumpets

What I don't know about flowers would fill a much much longer poem

Paper cup in the flower bed of you I know the species

Sun feels good the sky had only trace elements of cloud

Is this my place my time to shine my element my mind?

The river lumping with barges one has detached metal scoopers gigantic

Yellow and red like mustard and ketchup like blind mouths biting the surface

Under the corncobs now an impression of whiteness but they're really not white

Just open to the sky and curved like cellular biology

Suddenly under a tent they're setting for lunch at Smith & Wollensky

Where the Cajun Marinated Bone-In Rib Eye goes for 49 and the Butcher Burger for 13

Think I'm getting hungry and it's State Street so time to swing north

Curious inscription on the bridge house PRESENT BRIDGE BUILT IN 1949

"Present" is something persistent apparently capable of linking worlds

Now I'll see more foot traffic still thinking about that woman

I decided that she was a woman and I should have given her a buck

Since change has apparently no value the climate march in New York topped 400,000

That's a lot of pennies but still it seems like change for chumps

Given the stakes how can air still be crisp and delightful if impure

Bus kiosk Queen Latifah who is "Up Close and Personable"

Passing the Museum of Broadcast Communications pictures of Agnes Moorhead and Ira Glass

The rest have faces for radio the sun hasn't penetrated here

Passed by a bald man in his sixties in orange jeans blue sweater round sunglasses and white tufts of hair above his ears

I look like any asshole walking around tapping on his phone

Alley full of dumpsters young kerchiefed guy pacing with a cigarette

Two identical cubes across the street except one's a garage and one's made of brick

It seems like no one comes to the sidewalk anymore except as an excuse to smoke

Except for that woman in a black hijab crossing the street looking at her phone

White guy in a Bears shirt and madras shorts is really rocking his look

Better the young Asian man in a slim-cut suit and no necktie

There's the Hancock again its rabbit ears tuning in to the sky

Under onion domes of Bloomingdales like a deconsecrated Orthodox church

I think that after class I'll hike back down Michigan to the Art Institute

Visit my Sargent paintings and say farewell to Magritte

The REDHEAD Piano Bar Chili's Quartino Self Park Michael Anthony

Cop sauntering toward me wearing a backpack like a grade schooler

A couple in neutral colors holding hands as they cross Ontario

Here's a place with those woven chairs that make you think of a Paris cafe

But to return to inequality it seems these streets are pretty well scrubbed

Under towers of Erie a plumbing truck sticks its nose down into the sewers

Autocorrect wanted "seers" but I'm only skating on the surfaces

Of this Monday morning in Chicago September 22nd 2014

I think I know that guy no he's up and moved to New York

Put it on the blog where it has a chance of keeping company

Cadence of my eyes following State Street for mes devoirs

Holy Name Cathedral's receiving a touch-up on this day

From another reaching crane all of us two hands up harmlessly reaching

Now in wild overcompensation I give five bucks to a man in a wheelchair

Because how can I give him nothing when he asks while I'm writing a poem?

What any of us can do. This day is given to walking

Speaking French badly looking at paintings going home to my wife and daughter

As if what I love will remain, as if

"Your love will let you go on." No one here remembers California,

What Jack Spicer said.

September 19, 2014

Experience Points: The Dungeon Master as Poet

(first part of an essay in progress)

Geeks today rule the world. But to be a nerd or a geek twenty years ago was to be a marginal figure, as demonstrated by such period pieces as Revenge of the Nerds. Disappointed or frustrated by the limited social options presented to us, my fellow gaming nerds sought participation in a social world that from the outside seemed limited to ourselves, though it was in fact one of many coterie subcultures thriving and sometimes overlapping at that time. Such a coterie was, and remains, a society in search of transcendence. Gaming was an open door to experiences that the real world had seemingly foreclosed, either out of sheer mundanity (life in a cubicle) or because its experiential rewards (sex, money, power) seemed to have been reserved for the jocks and cheerleaders who were best adapted to that world. Role-playing games were for me, for us, our "systematic derangement of the senses"; they cleansed the doors of perception the way drugs did for our parents.

From adolescence on I was addicted to Dungeons & Dragons and other role-playing games (I still play occasionally). Most fantasy RPGs are a form of pastoral. Not only is the pseudo-medieval setting deeply conservative and feudal in its structure, but the rules themselves offer the players a kind of refuge from the real world's bewildering complexities. As William Empson observed, pastoral is always a simplification, and there's a clean and elemental quality to the rules and tables and dice rolls that compose a gamer's environment. Social interactions, in real life so complex and unpredictable (and generally unsatisfactory, particularly when it came to girls), were here quantified: if you had a Charisma score of 18 you were eminently likeable and you had the die-roll bonuses to prove it. The world of the game is highly coherent, not to say overdetermined: good and evil are clearly defined, and you can always kill monsters with a clean conscience (your friends too: if your character was "Chaotic Evil," say, you could backstab your buddies and then point to your alignment, as in the fable of the scorpion and the frog: "It's my nature!").

Most often my role was that of the Dungeon Master: the referee and chief storyteller of the game. Each player has a single role to play, as warrior or wizard, etc., while the DM plays everyone else: innkeepers, wenches, orcs, dragons, etc. I loved planning and prepping for games almost more than I enjoyed playing them, and spent countless hours in my room drawing maps on graph paper or writing up descriptions of the political systems of imaginary nations. When I got the chance to run a game, I usually ended up frustrated by my few players' inability to take the game world as seriously as I wanted them to; to try and hold their attention I'd shower their characters with gold and magic items in classic "Monty Haul" fashion. The actual games never lived up to the games in my imagination, but I persisted in playing them, because once in a while there would come a glimmer of that intensity, that heightened sense of life, that I craved, and that my everyday existence as a shy, pimply, unathletic, bookish beta male almost never provided.

Things changed dramatically in college, where I met a group of gamers as passionate as I was, brought together by our addiction to a new game called "Breakout." It was a homebrew ruleset and campaign created by my friend Josh Wright, who was probably the closest to an actual adventurer that I had met up to that time (the son of a well-known archeologist he had already done time at digs in Morocco and India; nowadays he himself is a landscape archeologist who specializes in Outer Mongolia). Breakout was more fluid and unusual in its concept and playing style than any game I'd encountered before. Not only could the player characters come from any setting, but the settings in which our adventures took place were constantly shifting, often without warning, from one moment to the next. Some of the player characters were of familiar D&D stock--fighters, magic-users, thieves, etc.--but we also had in our party 1940's-style private detectives and mystical gunslingers and a Catholic farmgirl from turn-of-the-century Texas and a Japanese anime character and the economist Paul Volcker (played by a prospective econ major with wild enthusiasm for Volcker’s tenure as chairman of the Federal Reserve—as I recall, his version of Volcker wielded a quarterstaff with surprising effectiveness). Sometimes we operated in a typically pseudo-medieval fantasy world, but there were other times we found ourselves on a spaceship on the fringe of a dying galaxy or in a Middle American supermarket that was under attack by zombies. It all seemed to make sense at the time, for we felt ourselves to be advancing along the lines of a classic good vs. evil plot that was also about--not just about, it was--the creation of the game universe itself. Terry Gilliam's 1981 film Time Bandits does the best job of any film I can think of conveying what it felt like to play.

One of Josh Wright's mantras, frequently on the lips of the various non-player characters we encountered, was Free your mind and your ass will follow. Sometimes, having passed various tests within the game--sometimes tests we didn't realize we were taking--our adventurers would find ourselves translated from one world to the next, just as the dwarfs in Time Bandits find themselves tumbling from one cosmic locale to another with the aid of their mystical Map. Sometimes transcendence of a given locale took the form of rescue and escape. Sometimes we were catapulted into greater peril, even insanity and horror (H.P Lovecraft and Chaosium's Call of Cthulhu made up a significant portion of Breakout's DNA). As in life our choices mattered, but the results were unpredictable and sometimes we felt ourselves to be caught up in a pattern that we could never fully comprehend. It was a game of riddles and hints and enigmas--every session Josh handed out a "quote sheet" of cryptic sayings collated from pop culture and past sessions that suggested the theme or arc that we would try to follow or bend for that day. Sometimes we tried to force things, translating the level of confrontation from characters in the gaming world to player versus game master. The results were generally disastrous results; as Alfred North Whitehead notes in Process and Reality, "Insistence on birth in the wrong season is the trick of evil." But birth is still birth, and it was possible to suffer death and defeat within the context of the game and yet believe, as one could not quite believe of mundane actuality, that such suffering would be redeemed by the ongoingness of the story. (Besides, one could always roll up another character.)

Breakout was, in short, different from Dungeons and Dragons and the other role-playing games I'd played. The rules, cobbled together from half-a-dozen different sources and from Josh Wright's own mind, were always evolving. There were no alignments and the morality of our actions and those of our foes were often murky. If you wanted to charm the snake priestess into releasing you from bondage, you couldn't just make a Charisma roll, you had to act it out. And the world itself was constantly shifting under our feet: our adventures were enjambed, a collage of whatever struck us as cool that week (some of the predominant influences of that time and place: Japanese anime, especially Akira; Highlander; Stephen King's Gunslinger novels; John Carpenter films, especially those starring Kurt Russell; William Gibson; The Terminator and Conan the Barbarian; Terry Gilliam movies; Alan Moore; etc, etc.). As game master, Josh Wright was the ultimate arbiter of the rules and the world, but we as players had considerable influence on how the game was played and on the evolution of its world. It was a story we told together that was sometimes more compelling than real life. (Okay, it was almost always more compelling than real life. My college transcript will attest to this.)

For a few decisive years, Breakout was life: life lived with intensity, vividness, transcendence. Not the brute transcendence of the adolescent power fantasy, or not completely so, but the transcendence of adventure. The root of the word is the Latin advenire (to arrive) and adventurus (about to happen), and it is very close to the idea of becoming. I began playing with a lot of resistance to this idea, actually. I spent hour upon hour creating characters in Josh Wright's dorm room, dreaming up idealized and magical personae for myself, with complex backstories that I typed up on my Mac SE and presented to Josh, who would receive them with an ironically lifted eyebrow. He understood, as I did not yet, that I was thinking like a D&D player, or a writer of fantasy fiction. Breakout was something else. The game world did not exist to ratify my fantasies; in fact, my elaborately designed heroes more often than not met absurd or humiliating ends.

Gradually I came to understand that Breakout wasn't like fiction, and that the most interesting characters were formed not by my mind working on its own but in the course of their adventures, which were after all as real as any of my other experiences in the sense that they were shared, the warp and woof of our little misfit society. Which was more meaningful: the backstory in my own mind or the actual adventure shared with comrades which we could then discuss and argue over in the days and weeks that followed? The spirit of adventure, of letting things come, ruled Breakout. As with the ancient alchemists, the acquisition of gold was not the true point: the gold was a virtuality. The success of the character or alter-ego that I used was not an end in itself, but a vehicle for transformation. The quest of the player had the same object as all Romantic questing, whether that looks like Percival seeking the Grail, Dante seeking Beatrice, or Scott Pilgrim taking on the world: more life.

What did Josh Wright get out of it all? I suppose I could just ask him, but I suspect the satisfaction he took in Breakout was not dissimilar to the satisfaction of any creative artist. But there was something particularly poetic, I think, more than fictive, in his style of gamemastering, in which language--the language of the rules, the language that accrued between us, with its many layers of reference--took on the form of action rather than representation, and which changed constantly, ramifying rather than linear. A kind of telling that in-formed us and our characters, that converted experience into selfdom; what Whitehead calls "the superject": the subject who is created by his experiences. Josh, who ran the game for two different groups (he called us "the Right Hand"; the Left Hand were his high school friends), got to be something like Whitehead's conception of God, created as Game Master by the collective prehension of the diverse elements of the game world, the only one with a complete view of everything it had become. As a poet becomes a poet by writing, by opening himself to the adventure of the poem.

September 7, 2014

Dark Culture

I wanted to find an outside to poetry. Not an escape, exactly, though there are times I wish that I could escape from poetry, which exerts its gravity on culture invisibly, like dark matter. Call it dark culture, which can be referenced by the grid but must be experienced off of it. (The grid can refer to poetry, etc., but when you experience poetry on the grid, what you really experience is: the grid.) Reading is a vanishing experience and the weight of all those books, more of them every year, is something perceived ever more lightly, something in-experienced. And yet it is possible to set the grid aside, or to use the grid still as reference or double to life rather than life itself, though we are fast forgetting how.

Poetry is off the grid and as dark culture its existence is untimely, precisely because of the ways in which it marks time. In writing a novel I could hardly expect to transcend these things. Instead I wrote myself more deeply into poetry, into my own line. The line simply expanded and extenuated, trembling on the brink of the sentence stretched to its limit. The sentence would not stay put. Its only satisfaction was the next sentence.

“Limits / are what any of us / are inside of” -- Charles Olson

Poetry is tasked for its irrelevance, its refusal to operate as an amplifier of tendencies already adequately represented by and on the grid. The grid, that endless surface the first world skates on--that this text skates upon--claims to offer us an adequate representation. The grid claims to be Borges’s “Map of the Empire whose size [is] that of the Empire, and which coincided point for point with it.” In fact the grid is the Empire itself. We feed it our existence and so feed its existence, compulsively and continually. Ungridded experience, itself merely a reference point, is “Useless, and without without some pitilessness was it, that they delivered it up to the Inclemencies of Sun and Winters.” IRL.

Culture is a multiphasic field in which we negotiate personhood: our appearances to each other, as individuals and as members of collectives. If you are a laborer in the fields of dark culture your work stands in an uncertain relation to your appearance or invisibility on the grid. The valuelessness of poetry is a commonplace, but so also is the ineradicable minimal value of being a poet. The grid is haunted by the specter of being-a-poet, which is a claim to personhood without authorization.

“I am unbaptized, uninitated, ungraduated, unanalyzed. I had in mind that my worship belonged to no church, that my mysteries belonged to no cult, that my learning belonged to no institution, that my imagination of my self belonged to no philosophical system. My thought must be without sanction.” -- Robert Duncan, The H.D. Book

We are back in Shelley’s territory of the unacknoweldged legislator. But my desire to find the outside of poetry, the skin of its dark matter, is not entirely Romantic. It’s an intutition that poetry does not represent experience but is an imitation of the action of experiencing. Poetry presents an image of what Alfred North Whitehead calls “prehension” in action.

I wrote a novel because I wanted a large prose field for prehension, which is both positive and negative. Positive in its selection of details or data in pursuit of a vector of cumulative experience--the past that composes me. Negative in its vast unselection, everything I don’t write about, whose pressure poetry can make felt. I don’t know if prose can. There is a horror at the center of my novel that to my horror has become part of the grid. What ought to bend or break the grid and put its thoughtless apparatus of representation has become integral to that representation.

Prose and poetry fall into dark culture when they are too insistently evental. The grid can only reproduce objects; it objectizes events. History vanishes into the twilight of my timeline; in the meantime, I can respond to it only affectively: I like it, I favorite it. Without analysis, almost without meaning, it passes by.

They say you should write the kind of book you yourself would want to read. But what I wanted to write was: reading.

Reading is in the dark. I see your shadow there.

"In the Deserts of the West, still today, there are Tattered Ruins of that Map, inhabited by Animals and Beggars...."

The grid tears easily when stressed. It is ill-equipped to represent without rupture or distortion the personhood of the non-normative, "Animals and Beggars," the feminine, the queer, the non-white, the poor.

Dark culture pours through tears in the grid for moments surrounded by incessant and ceaseless repairs. Converting time back into space, history into Empire.

Minions of the grid, bent and badly mirrored, only recognizable as human in the anamorphosis of dark culture.

The outside to poetry is time as it is lived. Poetry, like life--

Is mortal. In the line. I feel, enjambed--

"...in all the Land there is no Relic of the Disciplines of Geography."

August 7, 2014

After Creeley

One Robt.

Creeley rob-

bed words

from cradles

he’d

left rocking

in tempo

that hu-

man color or

vocal fry

takes seriously

man or

woman’s

advance

on adversaries

hidden every-

where the words

I find.

July 30, 2014

The Problem with Writing Articles

In academic halls, one writes for one's peers, and to satisfy their expectations--to win friends, to keep sponsors. Articles come first, small projects, research, translation--delicate nibbles at the hand that feeds. But an article is not an essay. Articles lie about the lay of their land. An article pretends to be clear about its objective and then must pretend to reach it. That objective will be minuscule though recondite. Moreover, the article does not halt at any point along the way to confess that its author is lost, or that its exposition has grown confused, or that there are attractive alternatives here and there, that its conclusions are uncertain or unimportant, that the author has lost interest; rather, the article insists on its proofs; it will hammer home even a bent nail; however, it does not end on a howl of triumph but on a note of humility, as if being right about something was quite a customary state of affairs. Polite applause will be the proper response. And a promotion.

- William H. Gass, "Nietzsche: In Illness and in Health"

July 6, 2014

On Knausgaard, Stupidity, and Being Seen

In which the link between stupidity and being seen is demonstrated.

It is nearly impossible to explain why the vague feeling of being seen and believed should make me begin to write a novel and take my writing much further than I had ever done before.

— Karl Ove Knausgaard

In a typically rambling yet as typically profound essay, Karl Ove Knasugaard writes of his relationship with his editor, and more broadly of what has emerged as the chief concern of his llfe and writing: the unstable boundary between meaning and the meaningless. The essay tries to account for his relation to those people with whom he has not struggled--his mother, his wife, and his editor--those who have given to him unconditionally, as opposed to the antagonists who have generated the narrative of his life, quite literally giving him something to write about--above all, his father, but also his brother and his own children. What these people give to Karl Ove is something rare but necessary, to any writer, probably to any human being: the experience of being seen: "seen, not from above, not from a distance, but from the inside."

I think Richard Hugo must have been thinking of this ineffable relation between writer and editor, or between student and teacher, when he remarked that "A creative-writing class may be one of the last places you can go where your life still matters." We all have a need to be seen, to be visible, and not only in the fast and thoughtless way made possible by the Internet and social media. There's being seen in a slower way, in a way bound up with what Knausgaard calls "trust." By these lights, the most important job of the editor or teacher is not to "improve" the writer's work, but actually to call it into being, the way a shaman intervenes with the spirits, first and most importantly of all by believing in them.

Knausgaard rejects or reverses the notion of writing as "practicing a craft": "To write means that you must break down what you know and have learnt, an unthinkable approach for a craftsman such as a joiner, who cannot start afresh again and again." It is the editor's "courage" that makes it possible for the writer to sustain this experience not simply of not-knowing (a kind of zen "beginner's mind") but actually destroying what he or she knows--a far more radical act.

Knausgaard writes revealingly of the clumsy, even "stupid" prose that balloons My Struggle to its impossible length. It is the stupid and infantile and regressive in Knausgaard's work that his editor has been most responsive to, what drives the writing away from "literature" toward "life." Knausgaard's pride is such that he will not go all the way--he is no Dadaist---"I could not bring myself to follow the editor's suggestion of removing my entire, carefully thought-out opening in high modernist style, so I hung on to it for dear life, since it proved that I was truly a literary author, that I actually could write and not just emote." It is the visibly dialectical relation between "literature" and "life" that makes My Struggle so compelling, and Knausgaard is insightful about the relation between the "infantile" and the "places where my field of vision has contracted: "The infantile passages are simple, almost like stages before something meaningful and coherent is created, while unravelling the knots of my constricted vision does the opposite and leads to an increased complexity, which points to a view of aesthetics contained in just these two observations, an attitude to what literature is, that has made me attempt to get away from the limitations that are inherent in language and can be conquered only by language."

To be seen means to be distinguished, and to encounter distinctions, which are also always limitations. Knausgaard writes about the "dismantled boundary" that arises in the conversation between writer and editor: "when a boundary is crossed, the act of crossing it makes the boundary more visible." In this intimate conversation the solitariness of writing comes up against the social which is at once the enemy of art (because it habituates and dulls perceptions) and the only meaningful arena in which art can appear. Knausgaard sees the dismantling of boundaries as paradigmatic of the past forty years, that is, his (and my) lifetime; he writes of the experience of reading Deleuze as a young man and getting the news from him, in the sense of the "news" William Carlos Williams says we must get from poems. From Deleuze, Knausgaard writes, "We absorbed concepts like openness, reactivity, mobility, unboundedness, interconnectivity, networks, horizontality. Nowadays, these are part of our reality, new ideals that society struggles to reach while it tries to leave behind all that is closed-in, limited, fenced off, constrained."

Knausgaard, as readers of My Struggle know, is temperamentally appalled by this leveling, even as he acknowledges that the arc of indistinction bends toward greater equality. Here is his essay's most characteristic paragraph:

A longing for boundaries is contained within almost all I have written, as well as a longing for the absolute, for something that is not relative and will last. With this goes a strong distaste for the unbounded, the levelled-down, the relativistic. These two strands, if followed, lead away from culture and out into what my longing is reaching for, into nature and religion. My mind is drawn to settlements, limiting and immobile, because the boundaries drawn around them define distinctions and distinctions create meaning. To write entails precisely that, to create distinctions – and specifically, within what is alike: only through being written about can what is alike become unlike, because it is given form and becomes something that is distinct from something else.

It is here perhaps that Knausgaard comes closest to indulging the darkly atavistic tendencies hinted by the title of his masterpiece, Min Kamp. But as the essay continues, we see him being dialectical about these tendencies. He brings out the dark side of indistinction when he recognizes its leveling effects as a core function of capitalism. And the dialectic also stands between Knausgaard and his editor, whose idelogical instincts are fundamentally opposed to his: "There is a tendency toward relativism in much of my editor's writings, a desire for the non-monolithic, anti-absolutist and egalitarian, in other words, something that goes against the desires I express in my writing." This ought to have made their collaboration impossible, as Knausgaard remarks, but then, sounding almost exactly like Adorno, he concludes that "even 'the alike' is not alike and the likeness ideal will be affected by whatever area it develops in and become unlike." That is, it is a function of writing itself to render unstable the boundary between plot and event, ideas and objects--or to find the objects in ideas, to challenge and divide ideas into objects of experience, limiting the unlimited.

Knausgaard is very fortunate to have found a doppelganger or ideal opponent in the form of an editor who calls Knausgaard's writing out into the open, into the visibility of the boundary between, say, Knausgaard's normative Scandinavian socialism and the impulse toward "settlements, limiting and immobile"--something that I suspect he will deal with most directly in the final volume of My Struggle, which is said to include a 400-page essay on Hitler and the mass murderer Anders Breivik, far darker doubles for Knausgaard than any editor could possibly be.

"To write and read means, at its most profound, to search for freedom, for routes into the open and it is the search for freedom that is fundamental and not whatever one tries to be free of, be it an identity, an ideology about equivalences or an idea about reality." To be truly seen--by an editor or a teacher or a reader or a friend or a lover--is to be given both an identity and the possibility of freedom from that identity, which might include the freedom to create a richer and more profound version of oneself. Writers and readers are in flight from the pain of being seen in unfreedom, from being marked and "recognized" rather than "seen" (I am using these words in Viktor Shklovsky's sense). This is why the precept "Write what you know" so dangerous: too many writers (and too many readers) seek confirmation of their given identities rather than freedom with-in them.

Only "enstrangement"--in Knausgaard's case, the enstrangement of "stupidity" that the dialogue with his editor makes possible--makes seeing possible. The writer needs an editor or teacher or simply a friend, even an imaginary or dead friend (Shklovsky himself might do in a pinch) to see what she has done and what she might do. The reader needs the kind of writing that Knausgaard shows us the way toward: writing of the dismantled boundary, alive to the struggle between art and life, the meaningful and the meaningless, the process of life that a processual and open literature--that risks stupidity and the unliterary--can make us see.