Joshua Corey's Blog, page 18

July 1, 2014

Ithaca and What's Next

Back in Ithaca, my intellectual hometown, the last place I was a student, pretending to be a student, outside the Gimme! Coffee on State Street (now Martin Luther King Jr. Street) where I wrote most of my dissertation, on sabbatical, smelling cigarettes, feeling the in-betweenness of things. Reading books I found at the used bookstore owned by my former employer Jack Goldman, who's still kind enough to give me an employee discount: Richard Rorty's Contingency, irony, and solidarity, John Dewey's Experience and Nature, Ann Charters's strange 1968 monograph on Olson and Melville. Also carrying around Hannah Arendt's The Human Condition, Hilda Hilst's With My Dog-Eyes, Ernst Meister's haunting In Time's Rift, as translated by Graham Foust and Samuel Frederick (Sam was in the Finnegans Wake reading group I belonged to in my Cornell days, so that's another fragment of my Ithaca past).

Reading, and writing, though most of the writing is gathered from old notebooks (a phrase I'll forever associate with Evan Lavender-Smith's novel). Trying to pitch things forward. My first novel has been officially out for a month now: I'm grateful for the favorable notices it's received (here and here and here, and also here) but as always in my experience publishing a book is like dropping a radio-controlled model submarine in a pond: you let the thing go, you wiggle some levers and give the remote a shake now and then, but you have no idea if it's getting anywhere or has run aground or if anyone else has noticed the slight ripple in the algae-strewn waters of literature.

A book needs readers to live. Yet the essential work has been done: devoting three-plus years to writing a novel has changed me and my sense of what's possible. Rorty reminds me that the self is not "out there" or "in there" to be discovered: it is made, formed, by successive interventions and descriptions. Am I a novelist? The question is a bad habit I need to let go. In his very flattering review, R. Alan Clanton calls my novel "a 369-page-long poem," and "a hundred long-form poems compressed deftly into the singularity known as the novel." Implying that the novel in its density is a kind of dwarf star or black hole; I think of Lorine Niedecker's phrase, "this condensery." Apparently there is no layoff for me from the condensery of poetry: I wrote prose and Clanton calls it poetry. Habit, destiny, choice? I wrote a novel in good faith, I think, one of the kinds of novel that I like to read: dense, poetic, baring its devices, questioning the possibility of storytelling as its means of telling a story. My models and influences were European, or inflected by the European: Calvino, Bolaño, Woolf, Saramago, James. The novel is not about a poet but a "new reader," who through obsessive reading of novels and poems and her mother's letters falls into fantasy, into the novel that contains her, a detective story, an attempt at redescribing history (a personal history of the twentieth century, its traumas and echoes) so as to redescribe herself. To return to the middle of things, in medias res, to life, in and through fantasy, reading and writing.

What comes next? If you're a reader of mine it's The Barons, my fourth poetry collection, coming in October from Omnidawn. It's a book of outrage, wrestling with epic, offering a different kind of resistance to the dead descriptions that chain us to the dead century we just can't seem to quit: echoes of the cold war, of the most violent and primitive forms of religiosity and tribalism, scaled horrifyingly upward by the capabilities of modern media and the modern state, themselves teetering on the brink of unimaginable transformation. I am writing my way forward, trying to find a language of the Anthropocene. The Barons is the first book in a projected trilogy that includes two manuscripts in progress: The Spoils, confronting revenant ideologies with the vitality of materialism, and an as-yet untitled project in which replicants of Hannah Arendt and Martin Heidegger struggle with each other against an apocalyptic twenty-first century backdrop. It's tempting to call the latter a novel, but in writing it feels closer to theater or gladiatorial combat.

Mixed up in all of this, elusively, the personal. Almost all of my writing, in any form, has had the properties and intention of exorcism: my mother, more than twenty years gone, is the beautiful soul I evade and appease and elegize. Foolish to pretend such exorcisms are ever completely successful. She is the twentieth-century ghost that haunts me, whose life I try to expiate and describe and re-live. If her form is difficult to discern in my current projects that indicates only my own blindness, a secret constraint (Brian Eno: "Any constraint is part of the skeleton that you build the composition on--including your own incompetence"). I conceal from myself what I reveal to others, and vice-versa. Writing is a strange form of keeping faith, like any heresy.

Other projects and possibilities smolder just out of sight: short fictions and parables, poems that read like essays, a novel that's less novel, further engagements with Olson and Duncan and Creeley and Howe. I think about the vision of pragmatism, the powerful potential of the made-up to transform what we take being. I write, and erase. I circle back "home" to Ithaca and launch myself outward again on a spiral, I hope, of surprise. "I hunt among stones."

June 6, 2014

Nekuia: The Novel

That first-page feeling. Imbricated in an uncreated network. A context for loving life. The "I" appears like an effect of a record's rotation, silver spindle surrounded by gently bruised silence. Static. It's analog, this notion of a surface compatible with infinite depth. Pearls, nutshells, the needle. You bury the changes or hide them in a landscape. Pretending not to breathe. I was looking for an appropriate unit of syntax: the root of appropriate is property, also to propitiate gods. What's the smallest pinhead and the maximum number of angels? If it keeps turning a character might happen. Not only a voice. Stimmung between the lines. Prose makes for between like vinyl: another obsolete technology of the word. Tiny notebooks. "You must restart your system to complete installation of updates." Which come from nowhere, like all data that's appropriated, from the cloud. Human hand, mine or anybody's, holding out a key, a tiny glass heart, or simply pointing to X. This is not productive but it stokes the means of production. Do women also call it jerking off? Reminds me of the context, which means something like to weave with. Warp and woof. The seamy side that shows you how it's done. The man who'd accept a coin in his cup and crinkle his eyes to assure me that whatever has happened to him is not my fault. He has a white beard and a yellow mustache. To. The needle rides the grooves like a little transcendence, I mean a really little one, it doesn't bother anybody. We can go on acting like wised-up materialists. Grain of the voice. The undescribed and now belated feeling of paper sliding underneath the skin of the bent fourth and fifth fingers of my writing hand. Whereas lefties, like elephants, never forget. I'm not trying to escape determination, not really. When this ends it will simply stop and you can assume a complete stop. Not a paratactic gesture toward the numinous, or a thumb jerked at capital's curtain, exerting its weak force on molecules like a supermoon touching the sea. We're done challenging texts to pistol-duels at dawn. We go to bed early and get up the same. I'm driving this car as far as it will go. After that I'll bicycle, after that I'll walk. There is no public transportation. It's good to be home. I am just a sentence in this badly translated prophecy. I am just a needle dragged raggedly off the turntable. I need to believe in a world that believes in me. I like it, like liking. There is a glacier somewhere acting exactly like the sky. Wind. High blue pressure of the thinkable. Best felt by spread fingers, by long hair, closed eyes.

I seek from reading and writing two complementary yet contrary things: the sense of a world in which my personhood (as hero, citizen, even as victim) becomes possible. And to surrender the self in intellectual or spiritual communion with another, him or herself a world in and through which connections come to light, myself only a node or synaptic gap across which these connections must leap.

This is a ghost story. Story of a ghost, of course, but also the story itself is ghostlike, doubtful yet insistent, recurring without coherence, insisting on a moment of recognition that can never arrive while you yourself are living. He held back his mother with the naked blade until the prophet could drink his fill. A story told and retold becomes myth and myth is nothing but a texture, a backdrop to life as it is lived, every day, with a sense of something behind the ordinary. Working walking talking sleeping. Of course, backgrounds are fatal to their foregrounds. When myth becomes the story, when it overtakes the everyday, both stories vanish. We are in the gray light that succeeds narrative and the word afterbirth is horribly appropriate. Bury the thing that feasted this life, for myth is deoxygenated blood. Dark and darker on the snow, in it. She is stargazing blind, hands outstretched, masked in bandages: her hands, I mean. Mummy in the snow, white on white.

The record, that lustrous boundary of a room's tone. Songs are not data. Inscribe that space with listening's effort. A man asleep on the sofa with an open book on his chest. Sun on the window, rain. Snow muffles the unheard. Only lifting the needle can wake him. The book slides to the floor: an event, almost. Begin playing it again--the outermost track of anticipation. Lossless. The audiophiles call it warmth, dimensionality. A lunar feeling. Placed in orbit, we infer a center. But we don't need a center. We have the song.

I disappear into the telling. Or I strike a stone and new voices appear, voices with one haunted face, telling stories that culminate in the only invisibility that matters. Catch it by the tail, that old story, before it freezes. Unwrap her gently, with reverence. Of course there's nothing there, there never was, except before the time of telling, of narrative, just the glide of an empty hand over paper. I am a baby in my bath, and she is near me. I am a grown man and she is gone. That is not a story, but this is: One morning, I awoke and felt a presence. A made thing. I spoke to, wrote toward, that presence, until it disappeared forever.

Night Flight to Berlin

Lufthansa airshow: the North Sea, pointed like an arrow toward Amsterdam over blue map water. While forty thousand feet beneath me the real pre-dawn sea roils and mutters. How we lose track of the sublime, how much we've surrendered--gratefully, thoughtlessly--to simulation.

Eliot should have said, Mankind cannot bear very much intimacy.

I remember it worried me a bit when I was a kid learning Beethoven was German. Because the Germans were bad guys, right?

Guten Morgen meine Damen und Herren. How beautiful the language is just to hear, with no comprehension, just glimmers, particles of meaning, like mica.

Ordinary lives in foreign languages.

Unexpected sun-flooded cuteness of Berlin, Charlottenburg, Winterfeldtplatz.

A cafe phrase, repeated and misheard, sounds uncannily like "Osama bin Laden."

Cigarettes! Smoked by people of an apparently affluent status now all but precluded from smoking in the U.S.

A falafel joint called Habibi. A bar called Slumberland (in English). Masha, a lounge or cafe, the word "cocktails" (again in English). Call. Amrit, an Indian restaurant. A wine shop and a candy store.

In my mind, hanging in the air between me and all these people with their handsome indifferent faces, not all of them white, the word: Jude.

What we would have named our son, had we had a son.

Rosh Hashanah in Berlin. The Brandenburg Gate, the gates of prayer.

I didn't expect mosquitoes. Or the brick church at the other end of the 'platz. Brick churches are in America, not here.

The kind of tired that trickles into you from the neck up. Sinus tired.

Red candles on cafe tables.

The note that P. strikes in his conversation, that his friend Claudio Magris strikes in his writing, that I think my mother had: a note of high irony mixed with a passion for beauty not easily distinguished from ethical passion, moral passion. Saturnine, satirical, an impression of sorrow skirting bathos, a nostalgia for Europe and its junkheaps, a doomed desire to find some right relation to the broken frieze of the world. Melancholy sensuality. A profound bookishness and feeling for culture--a sense of oneself as passionate observer, very nearly a participant.

Flawless light and air, "Berlin Luft," indeed! Passed by beautiful stylish European men, dressed youthfully but with iron in their hair. Yellowing trees. Frischkäse.

But underneath it all a heaviness, the density of history. Yellow stars.

A river we trail our fingers in, bearing us out, leaving almost no trace.

March 17, 2014

Stay Puft

I should have said, "It is also the nature of poetry TO DETERMINE OR AFFIRM one's relation to the incomprehensible condition of existence." I say "existence" because it is different than identity. I say "determine OR affirm" because there is an option here: the great sculptor Giacometti once said, "I do not know whether I work in order to make something or in order to know why I cannot make what I would like to make." Perhaps when one makes something one affirms, and when one tries to make and knows they cannot (another kind of making) one determines. One determines that they cannot, one determines this by endlessly attempting.

-- Mary Ruefle, "Madness, Rack, and Honey"

A number of truths on display here. One truth is akin to Walter Benjamin's thesis that "The work is the death mask of its conception." That is, the actual work is a thin and dead reflection of what was quick and living in the author's mind. One tries to grasp the conception, to capture it alive and in motion, but like the philosopher in Kafka's parable of the top, it is oneself that ends up spinning: the top is dead or undead, like Odradek.

But there are two opposed stances toward making here. To make a work "affirms one's relation to the incomprehensible condition of existence." And for a long time, I thought of my poetry as such a work, going back to the claim that Ruefle amends, that it is "the nature of poetry to assert individual identity." My ego demanded so many Mini-Me's, so many poems that, like Duncan's meadow in one quicksilver mood, were "a made place, / that is mine." The poems were objects, more-or-less exquisite, ends in themselves as people should be, themselves, ends.

But there are times when one cannot make a work. When working or trying to work ends in frustration and fragments; or (it is almost the same thing) when what one writes refuses to be a work like other works, like what one had faintly in mind. In short, one fails, and falls, into text. There is no work, like there is no Dana in Ghostbusters; there is only Zuul, minion of Gozer the Destroyer, who comes to the work of destruction indifferent to his form.

In the destruction of the work there is nothing to affirm. There is only the adventure of "crossing the streams," doing the unreasonable thing (as Charles Bernstein remarks in "A Defence of Poetry," "ratio... DOES NOT EQUAL / sense!"). To destroy the Destructor is not to affirm one's identity, or even "one's relation to the incomprehensible condition of existence." It means to roll the dice (which never will abolish chance) which will determine--for the moment--that relation. And we must roll the dice again and again. (Even if Ghostbusters III never comes to fruition; especially then).

Another more commonsensical interpretation of Giacometti's remark makes making a process of education: in trying and failing to make "what I would like to make," you learn a little more about it, and perhaps get closer to making, to affirmation. Or you can look at it in the mirror and affirm negatively with Beckett: "Fail. Fail again. Fail better." But I am a little suspicious of these aphorisms, which get passed hand to hand around the Internet until all the context--all the difficulty--has been rubbed away.

I am a little tongue-in-cheek with the Stay Puft Marshmallow Man, but my intention is a serious one. Ghostbusters plays with occult knowledge in order to make us laugh, but there is something more than a little sublime and terrifying about the form Dan Ackroyd's Ray chooses for Gozer, particularly after the crossed streams of their "unlicensed nuclear accelerators" have set him aflame. Ray tries to make knowledge harmless, to package it in the form of the friendliest possible commodity, and fails. "Poetry is the scholar's art" says Stevens, deriving from a vision of the imagination as "the sum of our faculties." It animates knowledge, and demonstrates the occultness of knowledge by giving it a sweet, tumultuous, and flammable body.

Knowing conjures; knowing is a summoning. Knowledge is made present by metaphor, and metaphor, as Ruefle reminds us, "is not, and never has been, a mere literary term. It is an event. A poem must rival a physical experience and metaphor is, simply, an exchange of energy between two things." Which echoes Olson: "A poem is energy transferred from where the poet got it (he shall have some several causations) by way of the poem itself to, all the way over to, the reader." Energeia: within work. Eventus, evenire: to come out of something. The event comes out of the energy that is within the work, that must be conducted with as little resistance as possible from the poet's knowledge (always occult and hidden: knowledge of the body, of history, of myth). It "rivals" a physical experience; it is a physical experience. It burns on the way out, and on the way in.

I am trying to understand the importance of the occult and the hidden; of the text as paradoxical fragment of the work (the energy) it contains; of the ghost in the small or large machine made of words. I am trying to understand the role of the occult and made-up, of the metaphors. Ruefle: "To conceive of things that don't exist is a natural act for a human being." What is the nature of making and of making-up? What happens when we answer the destruction of a known reality with the destruction of the unknown?

I ain't afraid of no ghost. Oh, but I am. And I am.

February 20, 2014

Circler

Set theory and Emerson teach us there can always be a wider circle, there is always a set that does not include every other set.

At what point does the new generalization become God? At what point of generalization does God become useless to us?

To purify words is to steal them, to claim a proprietary interest in blossom, in signs, in soul. To steal the fire of language and pay the penalty for it. What is the liver? An organ in unequal lobes to metabolize and purify. Without the liver there is no high. Chained to the rock tearing at the soft flesh with the beak-like needle, the needle-like beak delivering the possibility of ecstatic poison. The actor on his bathroom floor, fleshy no longer flesh. Look at me. The eye is the first circle. The eye travels over organs unseen by any save pathologists, medicos, rats. Praying on his knees in a dirty tent, clutching a few words for deliverance.

So Joyce wrote Dublin as a body twice, first in discrete sexed organs and again as sleeping Everybody snowing out a snoring storm of Shem and Shaun. You won’t out-book the Book. Dreams like dramas are not texts. Stage your dream over there: the actors, like shades in Hades, milling about with pages in their hands, waiting for the blood to run.

Over there, call it life but it’s not life. A newer Sevres pleases - / Old Ones crack. Stirred white sustenance. Draw a circle around comedy, around tragedy. I is immune to genre. Spill your guts.

For One must wait / To shut the Other’s Gaze down - / You - could not -

That torso, chipped cup brimming —

But these are all lies: men have died from time to time and worms have eaten them, but not for love. What stake in denying this?

Hooks, eyes —

Words and images implant desires that are not mine. That are mine, they are so close to the heart. A made place, the names. Repeatingly.

February 6, 2014

Proof of Life

Always startling when writing abruptly takes on material status very close to its final form. A long slow-burning sort of thrill to hold the proof of it--my first novel--in my hands.

January 20, 2014

Charles Baudelaire's "Correspondences"

"Nature" is a temple of living crutches

Sometimes oozing muddled words;

Man passes through this symbolic forest

That follows him with its vulgar eyes.

Like distant echoes confused by distance

Into a tenebrous singularity

Vast as the night, as clarity

Answered by sight, by sound and perfumes.

There are scents cool as the skins of infants,

Silken as oboes, fresh as meadows

And others opulent, triumphant and depraved

Generous as infinity

As amber, as musk, as balsam, as incense

Singing ecstasies of the spirit and the soul.

---

Correspondances

La Nature est un temple où de vivants piliers

Laissent parfois sortir de confuses paroles;

L'homme y passe à travers des forêts de symboles

Qui l'observent avec des regards familiers.

Comme de longs échos qui de loin se confondent

Dans une ténébreuse et profonde unité,

Vaste comme la nuit et comme la clarté,

Les parfums, les couleurs et les sons se répondent.

II est des parfums frais comme des chairs d'enfants,

Doux comme les hautbois, verts comme les prairies,

— Et d'autres, corrompus, riches et triomphants,

Ayant l'expansion des choses infinies,

Comme l'ambre, le musc, le benjoin et l'encens,

Qui chantent les transports de l'esprit et des sens.

January 14, 2014

Six Dimensions of Poetry

The turn, the break, "This Be the Verse." The Plumb through the void, at scarce determined times,

In scarce determined places, from their course

Decline a little-- call it, so to speak,

Mere changed trend. For were it not their wont

Thuswise to swerve, down would they fall, each one,

Like drops of rain, through the unbottomed void;

And then collisions ne'er could be nor blows

Among the primal elements; and thus

Nature would never have created aught.

Lucretius, The Nature of Things, trans. William Ellery Leonard

Heidegger says that only a god can save us. But Lucretius says we have no gods. Only the volta.

DOUBLING"I is another," says Rimbaud, castigating "the false significance of Self." The pronoun in the poem is the mask. The poem is the impossible touch of the other in the mirror. And the poem works by doubling: call it rhyme, call it repetition. How many flowers? "A rose is a rose is a rose is a rose is a rose."

A dimension is a question of structure.

CADENCEThe quality of time in the body (of the speaker, of the listener, of the line, of the poem).

SILENCELanguage is not identical with itself. Attentiveness to this.

Each dimension midwifes the emergence of the others.

THINGSLanguage is not identical with itself. Forgetfulness of this.

The rhythmic emergence and submergence of the referent. Immanent mimesis of the poem, which does not describe things, which is a thing in relation to the other things it does not describe.

OUTSIDEWhat the volta admits, what the language doubles, what the cadence remarks, what silence acknowledges, what cherishes the things.

The spirituality of the Möbius strip, which is a thing any child can make with a strip of paper and some tape.

The activeness of creatures without a creator.

What Hopkins calls "Christ." What Jews call

The Law. "There are no / final orders."

No home.

January 11, 2014

Hidden Leaves

"Find hungry samurai!"

A writer, PhD student, and Iraq veteran named Roy Scranton has posted an astonishing essay, "Learning How to Die in the Anthropocene," in "The Stone" blog on The New York Times website. Astonishing not only for its content, which deftly synthesizes a lot of the thinking on the anthropocene familiar to latter-day ecocritical discourse, but for being placed so prominently in a mainstream media outlet. Most astonishing to me is its juxtaposition of the warrior ethos known as Bushidō in its construction of a new ecological ethics; specifically, the ethic outlined in Hagakure ("hidden leaves"), the 18th-century samurai manual written by Yamamoto Tsunetomo, which advises the samurai to gain "freedom" by living as though he were already dead. Scranton read Hagakure while deployed to Iraq, and it seems to have kept him sane:

Instead of fearing my end, I owned it. Every morning, after doing maintenance on my Humvee, I’d imagine getting blown up by an I.E.D., shot by a sniper, burned to death, run over by a tank, torn apart by dogs, captured and beheaded, and succumbing to dysentery. Then, before we rolled out through the gate, I’d tell myself that I didn’t need to worry, because I was already dead. The only thing that mattered was that I did my best to make sure everyone else came back alive. “If by setting one’s heart right every morning and evening, one is able to live as though his body were already dead,” wrote Tsunetomo, “he gains freedom in the Way.”

In a remarkable rhetorical coup, Scranton goes on to extrapolate from his situation as a soldier in Baghdad to our situation in the Anthropocene, confronting the precarious death-in-life of modern civilization, a reality glimpsed in the form of Katrina, of Sandy, of our collective inability to put a meaningful curb on the tons of carbon pumped into the atmosphere every second. Scranton writes: "The biggest problem we face is a philosophical one: understanding that this civilization is already dead. The sooner we confront this problem, and the sooner we realize there’s nothing we can do to save ourselves, the sooner we can get down to the hard work of adapting, with mortal humility, to our new reality."

This argument will be familiar to readers of Bill McKibben's Eaarth: Making a Life on a Tough New Planet. But it's the "already dead" thing that startles. The warrior ethic of Hagakure is feudal: it places the highest value on honorable service to one's lord, which depends on the vassal's subdual of the fear of death. It's a form of stoicism, of indifference to one's fate, coupled to the most lively imaginings of that fate ("shot by a sniper, burned to death, run over by a tank..."). Paradoxically, as suggested in the blockquote above, this stoic submission to fate, which is homeomorphic to submission to one's master, leads to "freedom in the Way" (Bushidō means "way of the warrior").

Now it may sound strange, but when I read Scranton's essay, I found myself wondering about the place of joy and ecstasy in an ethos appropriate to the Anthropocene. Why? Partly because the imagining of the body as dead, while the spirit is alive only to service, is a bit too Gnostic for my taste. It suggests that we must become zombies, re-enacting alien desires that we can't actually feel. It seems to me that our widespread denial of what's happening, our obsession with trivial digital glamour, our frenzied consumption, etc., is precisely a manifestation of a death-in-life characterized not by stoicism but acedia (the medieval monk's disease of indifference to his salvation).

More significant, I think, is the fact that if one truly imagines one's death, and the death of one's civilization (if not the death of humanity or the death of all life), does not life in the present take on the savor and intensity it otherwise lacks? Full presence in the here-and-now is not possible without the vivid imagination of the final boundary. I suppose I am simply reiterating what Heidegger calls "Being-toward-death" (a nice summary of which by Simon Critchley can be read here). There is a kind of ecstatic vitality that comes with confronting the reality of death, an appetite for presence and connection (with others, with one's own body, with ideas and traditions), in short, a meaningfulness that seems affectively if not substantively different from the stoicism of Hagakure.

In Kurosawa's Seven Samurai, a village is threatened with exploitation and destruction by bandits. The villagers resolve to hire masterless samurai for protection, but have nothing to offer except rice. "Find hungry samurai!" advises the village elder. "Even bears will come out of the forests when they're hungry." Most of the samurai recruited fit the Hagakure mold: the two leaders of the band seem certain that this adventure will result in their deaths, and proceed anyway. There is also a young and untried samurai named Katsushirō who at first seems more interested in flowers and the beautiful villager Shino than in thinking about death. He is in awe, however, of Kyūzō, who embodies more than any other member of the group the concept of living as though already dead. Stone-faced and laconic, he is the most terrifyingly effective of the assembled warriors, and Katsushirō crushes on him even harder than he does on Shino (who when he first meets her, is disguised as a boy; there's a lot of interesting homoeroticism in this film).

Then there's Toshiro Mifune's Kikuchiyo, whom as the viewer eventually learns is no samurai at all. He's a wild peasant dragging around an enormous sword, who identifies fully with the villagers and their precarious situation in a way the other characters do not. He is a vivid, earthy figure, full of laughter and rage, completely undisciplined, completely passionate, and in short as far from the sober ethos of Hagakure as one can imagine. But his commitment to life is large: he castigates the "real" samurai for not understanding the hardships of the farmers' lives, and he dies protecting them.

There's more than one way to be a samurai, in other words. There's more than one way to imagine death. It seems to me that more of us could stand to be like Kikuchiyo: conscious of our borrowed armor, attached to the earth, willing to die to defend the village from whose fate we do not separate ourselves. There is a fierce joy to be found in life on the precipice, not in stoicism but in something closer to a Nietzschean amor fati. We all must die; all must die. Let's be alive while we're here. Which means a commitment to the everyday, which means resisting domination and banditry with any and every means at our disposal.

I think this possibilty--this dark joy--is what's missing from Scranton's essay; and it's the resource we most need if the village is to stand any chance at all.

January 2, 2014

"I return to sentences as a refreshment": Ambience, Consecution, the Open

I began writing what became Beautiful Soul simply as a series of sentences. Very long sentences, as it happens, with enough comma splices to risk revocation of my license as an English professor. A poet works in phrases and above all in lines; sentences are exotic. Nearly as seductive to me are paragraphs, very long paragraphs, the sort of long paragraphs one encounters reading Proust and Adorno and Saramago. Stanzas and strophes have nothing on paragraphs for their elasticity, their infinite yet tensile capacity. "Sentences are not emotional but paragraphs are," says Gertrude Stein. But the problem with sentences and paragraphs is not that they are emotional or unemotional. It's that they say things. And saying things, as I like to remind my writing students, is not what poetry is for.

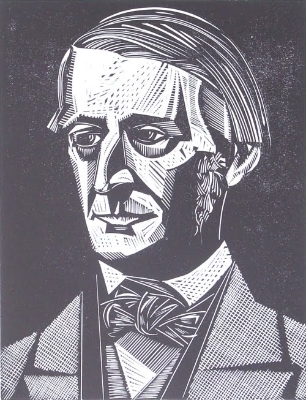

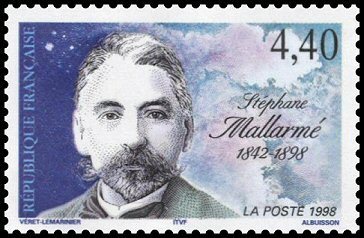

Mallarmé: "I say: a flower! and, out of the oblivion into which my voice consigns any real shape, as something other than petals known to man, there rises, harmoniously and gently, the ideal flower itself, the one that is absent from all earthly bouquets." Poetic voicing is inseparable from oblivion, from the invisible. But fictive voicing is all too mimetic, all too obliterative of oblivion. It is difficult for fiction to recapture its fundamental rhetoricity; it is difficult not to lapse completely into what John Gardner called "the fictive dream": "the writer forgets the words he has written on the page and sees, instead, his characters moving around their rooms, hunting through cupboards, glancing irritably through their mail, setting mousetraps, loading pistols." The reader forgets too. It's like Eliot's objective correlative, only without the objective part. It's language idealized, all spirit and no letter.

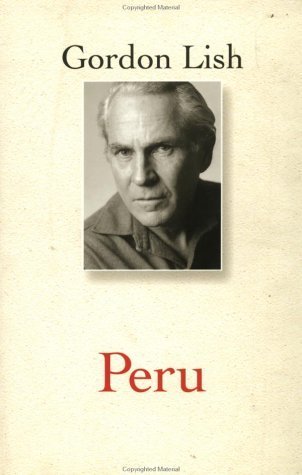

Fictive sentences don't have to work this way. There's Gordon Lish and his theory of "consecution," as explained in a valuable essay by one of his students, Gary Lutz: "a recursive procedure by which one word pursues itself into its successor by discharging something from deep within itself into what follows." The writer reacts to the material properties of constellated words and letters, and proceeds by association from one sentence to the next. In a manner somewhat akin to Ron Silliman's "new sentence," each sentence exists in its own torqued bubble, generative of and yet separate from the sentence that follows it (Lutz calls his article on consecution, "The Sentence Is a Lonely Place"). In a review of Lish's own novel, Peru, David Winters claims that for Lish, "composition cuts across ontology, not only aesthetics" (italics in original).

Winters goes on to compare the "cut" of consecution to, of all things, the clinamen of Lucretius:

"consecution may be less a methodology than a metaphysic; a miraculating agent; an instance of spirit or pneuma submerged in the world. In Lucretius, the force of composition is described as a clinamen—our world is born from a 'swerving of atoms in their fall from heaven. Such is the purpose served by Peru’s perpetual swerving, rhyming and recursion. Each consecutive swerve steps closer toward a total curvature, an arc that delimits the work as a world apart." Each Lishian sentence is its own world, its own monad, in which the universe of the story is contained without being merely represented. It's a mimesis beyond mimesis; the immanent transcendence of representation. The reader encounters the story as a sufficiency, as a world to be explored rather than as something presented. It's an essentially Modernist rather than postmodernist technique.

The Lishian "cut," the Lucretian "swerve": these are comfortably poetic concepts for me, reminiscent as they are of the volta or turn that is central to the operations of verse. The more-than-semantic, physical cut-in-language of the volta is what charges a poem with energy unsupplied by subject matter. Poems cannot completely evade subject matter; words never can. But they come much closer to such evasions, and can entangle a reader in themselves, with a more intensively minimal mimesis than can fiction. And this perhaps is why Yeats can say that poetry makes nothing happen but rather "survives, / A way of happening, a mouth."

Fiction is also a way of happening. And yet to be fiction, something has to happen. To write it, there has to be story. But there's a problem with the Lishian ontological sentence: it's too definitive and determinate. It says things.

A happening is an event. In a recent essay on "the novel as event," Cooper Levey-Baker seems to mean something less eventlike than the scene of events (way of happening): something like architecture or ambient music. Touchstones for his piece include an artwork by Anish Kapoor (creator of Chicago's beloved Bean, aka Cloud Gate) and the collaborations of filmmaker Béla Tarr and novelist László Krasznahorkai. Levey-Baker seems interested in recapturing a particular dimension of Modernism: the challenge to the reader or viewer to encounter the artwork (a film or a novel) so as to make its silence audible, often to the point of discomfort: the unpleasures of boredom. The very long shots without cuts in Tarr's film version of Krasznahorkai's Satantango are the equivalent of the novel's very long sentences, which endlessly defer answers to the audience's questions about what exactly is going on. As at a poetry reading, or leafing through one of Ashbery's longer works, one's mind wanders without ever losing the sense of being in the presence of something, an environment in which the figure-ground relation is rendered ambiguous, if not threatening.

Boredom, Levey-Baker claims, is the last refuge of the avant-garde, the one affect that cannot be recuperated by the entertainment-industrial complex. Long sentences, in their excessiveness, their accumulation and angular momentum, do not have to be boring; but they do tend to be far more open than short sentences. In their attenuated hypotaxis, the extension and interaction of dependent and independent clauses begin to overwrite each other, to introduce a dubiety, room for interpretation.

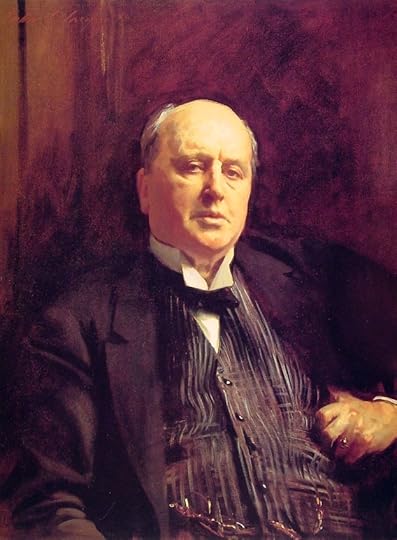

The past master of this is of course the Master himself, Henry James. Here's a sentence, chosen more or less at random, from The Golden Bowl: " He remembered to have read, as a boy, a wonderful tale by Allan Poe, his prospective wife's countryman—which was a thing to show, by the way, what imagination Americans COULD have: the story of the shipwrecked Gordon Pym, who, drifting in a small boat further toward the North Pole—or was it the South?—than anyone had ever done, found at a given moment before him a thickness of white air that was like a dazzling curtain of light, concealing as darkness conceals, yet of the colour of milk or of snow." This is not unstraightforward; and yet its dart backward toward an impugnation of the American imagination, its dart sideways into Poe, and its ambiguous image of the white mist of others' motivations (concealing the future of our hero) lend an astonishing multiplicity to the sentence's mimesis of what is supposedly happening in Prince Amerigo's mind. James is famous for his psychology, but thanks to his brother William's work we know how close psychology is to philosophy, which is to say the art of disclosing the real. Reality, as William James teaches us, is perspectival. The activity required of the reader of a Jamesian sentence sends her grasping in and through language for a meaning one cannot help but be conscious of creating.

James is also capable of Lishian sentence pairs, as in the following beautifully asymmetrical chiasmus: "He was taken seriously. Lost there in the white mist was the seriousness in them that made them so take him." The reader leaps from stone to stone. The cut is there. But it's the longer sentences that makes James James, and that suggest, for me, a possible fiction, an immanent mimesis, the paragraph-environment, story in language.