Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 167

January 3, 2014

What Do You Want From Your Writing in 2014—And Beyond?

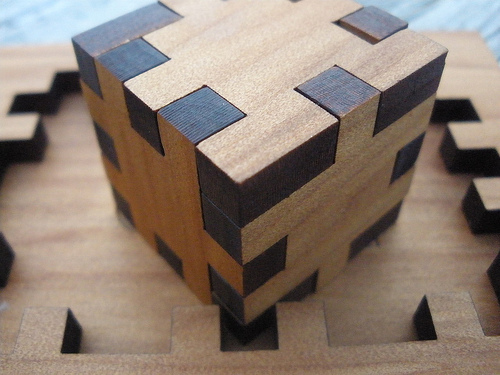

by viZZZual.com / via Flickr

Today’s guest post is by author Dan Holloway (@agnieszkasshoes), and is adapted from a chapter of his recently released e-book, Self-Publish With Integrity .

Do you know what you want from your writing?

Yes? Good. Now take a pause, and a pen, and a piece of paper, and write it down. It shouldn’t take more than a few seconds.

The interesting thing I’ve found is that whenever someone asks me that, I think “yes, of course I know.” And then I try to put it in a sentence. And I end up with a thousand-word article that throws up a hundred tangents. And the easiest thing to do is shrug, convince myself “I know really, deep down” and carry on.

Which is the opposite of what I should do. This isn’t like a toothcomb edit that’s best put aside till the first draft’s fully down. If you don’t know what you want from your writing, what on earth are you doing writing anything? How can you possibly tell whether your words do what you want them to?

It’s actually not that hard a question. It rests on a more fundamental one. Why do you write? Only we think it doesn’t, because in our head we think we can separate them out. “I write because I have to” is what most people will say, then continuing, “but I’d like to make a living.”

That won’t do. Why you write is always the key to what you want from your writing.

How do you find out why you write?

In many ways, finding the real reason why you write is a similar process to putting together a traditional submission pack for your book. It’s the same kind of exercise in getting right to the heart of the matter.

Many how-to advisors will tell you that you should have an elevator pitch for your book—a single sentence that captures the essence of what your book is about. I’ve always been skeptical about this—in large part, I’m sure, because I write the kind of sprawling, multi-narrative blancmangey books that seem to defy such distillation (that’s what I tell myself, anyway!). But when it comes to the reason you write, this is exactly what you want. A one-sentence elevator pitch.

Why just one sentence? Because if you allow yourself more, you will—just like you do with a not-thoroughly-edited-enough book—find yourself including everything you want to include, everything you think you should include. Because doing that avoids having to think about the one thing that matters most of all. The problem is that the lack of clarity will come back to haunt you later in your writing life, especially when faced with choices and opportunities and dilemmas the answer to which will mean pursuing one part of your goal but neglecting another, and then coming to rue the results.

Techniques for creating your one-sentence goal

One of the things that has been incredibly helpful for me, under the expert guidance of Orna Ross, was free writing—taking a subject and simply running with it, with no restraint, until I’d burned myself out on it and got to the real roots of what I thought about it. You might set yourself an exercise such as writing a letter to your future self, telling yourself what you want. Or you can write it from an older and jaded version of yourself to an imagined therapist, telling them why you are so disappointed with what the writing life has turned out to be. The key is that once you start, you keep writing. Once you have gotten all the things out of your conscious mind onto the page, you will be amazed what else follows.

Brainstorming and mind mapping are also techniques I’ve used with great success. They are not to be confused with one another. Brainstorming involves taking a blank piece of paper/notebook/whiteboard/untrammelled wall and a pen/pencil/crayon/can of spray paint and writing down everything that you think of on a subject. There are no rules, no techniques, just an orgiastic splurge of aphorisms that you will then, in a subsequent session, analyze to see what recurrent themes and surprising twists have been unearthed.

Mind mapping, on the other hand, is a more systematic approach to digging beneath the surface to find out what’s really driving you. I would highly recommend Tony Buzan’s seminal The Mind Map Book as an essential tool for every writer. It will take you through all the techniques involved in using mind maps to organize your thoughts.

Mind mapping is the perfect technique to use if you know what your general aim is—an aim such as “delighting readers”—but want to make that more specific, to find out exactly what kind of readers you want, and exactly how you want to delight them, what it will be like to be a reader intoxicated by your work.

The biggest enemy of goal setting: generality

There are two big problems with dreams that are too general:

A broad goal will encompass things you don’t really want as well as things that you do, which can lead to disillusionment. A really obvious example would be stating that you want “fame.” The chances are that what you mean is when people think of books, they think fondly of you. You don’t mean that you want the paparazzi camped outside your house waiting for you to fetch the milk on a bad hair day. So don’t say you want “fame.” Say you want to be a “top of mind” writer, someone whose name is synonymous with literary wonderfulness.

You never know if you’re living the dream or not. “What would it look like if I achieved my goal?” is a really important question to answer. But without a very specific goal, it’s unlikely that you will be able to answer it. The result is that you can end up spending years floating along, not feeling terrible about what you’re doing but not feeling fabulous either, just going from one thing to the next.

It’s only by spending some high-quality time narrowing down your goal to the level of the specific, the imaginable, the concrete, that you can avoid the pitfalls of the vague and general.

Whichever technique you use, or if you use them all together (which I’d recommend, as well as throwing in anything else you come across), the actual process itself will start to solidify what you really want from your writing in your subconscious.

When are you done with the process?

As you revisit your lists, maps, and free-written splurges, ideally a few days after you have finished creating them, this subconscious compass will guide you through the process of crystallizing your thoughts into a single sentence.

How do you know you’ve really reached an end point? For any goal you set yourself, is that the actual goal you are striving for, or does it matter to you for some other reason? If the latter is the case, then that other reason is actually your goal. For example, “I want to be heard” is what a lot of people say. That’s not very specific. For starters, by whom? But the real problem is that, in most cases, writers want to be heard for a reason. That reason might vary from “I want someone to understand my story” to “I want someone who’s a professional in the creative world to say I have talent.” Both of these specific goals could manifest themselves as the general goal “I want to be heard,” but they are very different, and achieving them will look very different. Which is why getting to the real goal is so important to avoid disappointment later.

Imagine what it would be like if you achieved your goal. Often, the very fact that you can do this easily, or the trouble you find with such visualization, can be a clue as to whether or not this is actually what you want. Difficulty in visualizing what life would be like if you achieved your goal may mean that goal is still a little too general.

Crie de Coeur

By the end of the process you should have a single, specific thing, the thing you really want from your writing, the thing for the sake of which you want everything else. Your task now is to express that goal in a single sentence. Get it right, and make it punchy. It’s the single most important sentence you will ever write. It is your crie de coeur, your battle cry. It will sustain you and provide a compass for your entire writing journey.

Once you have written that sentence, write it out (or print it out but writing is better, it makes you more connected to it) on a piece of paper, laminate it, and pin it to the wall above your desk. Make yourself business cards with that sentence and put them in strategic places. Customize a skin for your tablet or smartphone with that sentence written on it. Remind yourself of it whenever and wherever you can. You can even make it the tagline of your website. This is your definition of success, the only definition that matters to you from this moment on.

The post What Do You Want From Your Writing in 2014—And Beyond? appeared first on Jane Friedman and was written by Dan Holloway.

January 2, 2014

New Year’s Restitutions | Writing on the Ether

Table of Contents

Nobody Dast Blame Us

Maass Production

Wendigging It

Nobody Dast Blame Us

You know the line, right? It’s Charley, in Death of a Salesman:

Nobody dast blame this man. You don’t understand: Willy was a salesman. And for a salesman, there’s no rock bottom to the life. He don’t put a bolt to a nut, he don’t tell you the law or give you medicine. He’s a man way out there in the blue riding on a smile and a shoeshine.

An infographic provided to the Ether by Goodreads on the Amazon-owned site’s 2013 successes. It shows us that some 25 million people were talking more about books than about the book business: There may be hope yet.

—

And we’re all salesmen on this bus. The books bus. If we weren’t before, we are now. We have every right to be wickedly focused on the business end of things.

Here at the opening of the 344th Year of Our Digital Disruption—how long, O Lord, how long?—there’s nothing surprising about the obsession gripping the industry! the industry!

The digital dynamic does not and did not change the creative process.

No, it bites you on the business end. Distribution is its engine. The marketplace is its test track. Your career is its parking lot.

A lot of our colleagues never meant to be salesmen. Not really. Sure, sure, everyone in life sells something, etc., etc., but I’m talking about the near-eclipse of art by commerce that has occurred while the transition monster-trucked its way through publishing.

You couldn’t see one of the 8,762 obligatory stagings of A Christmas Carol this holiday season without somebody telling you that Charles Dickens was a great serialist. Would everyone please stop telling us that? We know, Dickens released in serial form. Got it. Does anybody talk about what Dickens wrote anymore? What those stories meant? How he crafted his characters or what he wanted us to remember about them? Do you really think he wanted us to dwell on the fact that he released stuff in serial form? Me either. I think he was making more important points about life than that. So could we move on now, please?

Likewise, you can see this reductio ad business in the 2014 edition of the Writer Advice Day Palooza that bombards us with teeth-gnashed writer-advice confetti each year.

As Elizabeth S. Craig put it in her, How To Meet Our Goals in 2014, “Since my blog reader was so chock-full of writerly advice for the next year, I felt I needed to run a post as an antidote. ”

And her antidote is a good one, especially if you’re in the grand-goals camp. She writes:

How low can you set the bar and still get what you want? I know that sounds awful, but for me, that’s how I achieve—I hit all my goals and that motivates me to keep hitting goals. And if I hit my goal and keep going and write more…that doesn’t mean I don’t write the next day. The next day I meet my very modest goal again. With modern life—we’ve just got to be realistic about our time.

[Only writing tips you need]: How to say nothing in 500 words: http://t.co/124lGi2auN & 10 Tips from David Ogilvy: http://t.co/N1dewSdRhK

— Adam Singer (@AdamSinger) December 12, 2013

I hashed a brace of tweets on January 1 #HappyWriterAdviceDay. It’s been more like Writer Advice Week, of course. Almost charming. If Meredith Wilson’s The Music Man had been The Writing Man, we’d all be out in some desperately small-town-Americana town square telling each other how to do it. That’s what Writer Advice Day/Week is. Authors telling authors how to do it.

New Year really brings out the evangelist in so many of our good friends, doesn’t it?

Most of the posts I found for #HappyWriterAdviceDay featured our best and brightest telling our brightest and best that they have to write at least 500 words each day damn it, no matter what. Even if both your arms fall off and the power goes out, you still have to write 500 words each day damn it. Your spouse may die, your children may put out each others’ eyes with their Hunger Games archery sets, and terrorist attacks may collapse buildings on your head, but you have to write 500 words each day damn it, that’s it, that’s all, amen and awomen.

500 Words a Day: The Secret to Developing a Regular Writing Habit http://t.co/eJ7T3hYttB via @jeffgoins

— Joe Bunting (@joebunting) January 1, 2014

Some of these aren’t resolutions. They’re recriminations. Self-recriminations. The person who tells you most loudly that you have to write 500 words each day in 2014?—just might be the one who didn’t manage it (damn it) in 2013.

But I’ll say it again, in everyone’s defense: we’re being driven to this stark-staring fixation on word counts by the Digital Enablement. Nobody dast blame us. This is Boom Town, baby. Everybody can publish, publish, publish. Who cares if you have nothing to say? Write a book, anyway. No, write four. Per year. If you don’t, you’re a wuss. Five-hundred words…I told you that part already, right? Okay.

I have committed to writing 500 words a day for January. Now to figure out the focus as it could be the starting of a book.

— Belinda Squance (@BelindaSquance) January 2, 2014

So amid all this content-more-content-faster-content cacophony of #HappyWriterAdviceDay, imagine my relief when I found Donald Maass, my fellow contributor at Writer Unboxed, writing:

There’s all the time in the world today. It’s a day for resolutions and lists, every item of which feels doable. The slate’s wiped clean. The calendar is a hopeful expanse just waiting to be filled with shining accomplishments and earned satisfaction. All is possible. Nothing is too difficult. The view ahead is clear.

When did Maass become such a relaxing person? That agency of his is about to open a maassage service, mark my word and get me an hour-long appointment as soon as it’s up and running.

Got a huge exercise streak going. So far this year I've worked out every single day!

— Chris Guillebeau (@chrisguillebeau) January 1, 2014

Maass Production

Today’s a good day to get off the highway. Give yourself some time to stretch. Have a coffee. Dream a little. Summon your ambition. Feel your power. The novel you’re working on has the potential for greatness. Today’s the day to discover it, own it, and plan for it.

Donald Maass

In this pause of the assembly line, Maass recommends you ask yourself a few questions about what it is you’re writing, not about how much you’re writing.

When readers finish your novel, what will they feel most strongly? Which event in the novel should most strongly provoke that feeling? How can you enhance that event to guarantee that result in readers?

Are your eyes brimming yet? His piece is called Novel Resolutions. Novel, indeed, because he doesn’t mention word count damn it.

What makes novels in your category weak, derivative and predictable? Catalogue those elements then take a look at your own manuscript. (Come on, be honest.) Work out changes that will counter your readers’ expectations.

Wow, I didn't realize my book was only $2. Holiday special, perhaps! http://t.co/O2OWKVelRx

— Jason Merkoski (@merkoski) January 2, 2014

This next bit from Maass may even be illegal for open conversation in certain boroughs of Manhattan:

What makes a novel a classic? List the qualities. How can you enact each of those qualities in your pages?

He’s talking about literature. Classic literature. Remember that stuff? Wouldn’t it be amazing to restore some of our commitment to the work itself this year, not just to getting smarter and faster at producing it?

(Literature means all genres, thank you, and I’m looking at my one reader who loves to tweet at me that “literature” means only literary. I should have given her a dictionary for Christmas.)

Before you dive into that new year's resolution TBR pile, tell us: is it possible to read too much? http://t.co/AtBz8UllpZ

— Book Riot (@BookRiot) January 1, 2014

What I really appreciate about Maass’ essay at WU is that he doesn’t slam us with another refrain of “Trouble Right Here in River City” about butts in seats and hands on keyboards. He actually advises you to take a moment—which didn’t have to be on New Year’s Day, do it now—to think about what you meant to write, what you may or may not be saying in a book.

For this, I’d like to shake his virtual hand. What a great thing.

I found a bit more headed in this direction, and I’ll offer it to you in case you, too, are tired of “the product” and would like to spend a little time thinking about “the meaning.”

I make no resolutions anymore b/c I don't like to disappoint myself.

— ljndawson (@ljndawson) January 1, 2014

Wendigging It

Publishing is a container, and while choice of container is certainly important, it’s not the reason you’re here. If the only thing that makes you interesting is how you publish, your time in this creative place has a very short clock.

Chuck Wendig

This is Chuck Wendig. And I cannot say that in Writing Resolutions: 2014 and Beyond, he doesn’t push hard at the importance of actually doing the writing. Without telling us about the 500 words each day damn it, he does make it wonderfully clear that airy-fairying off into the nana of poetic promise won’t get the job done:

You should firmly get your order of operations straight: the writing comes first. The talking-and-reading-about-writing comes second. Writing advice is here to support your art, not support the illusion of your art.

But Wendig, a prolific producer, himself, mind you, brings some interesting observations to the table, in that special patois of his.

Now my head hurts

MT @jobsworth: Tend not to have New Year resolutions. If I harden that tendency, does it then become a resolution?

— Mathew Ingram (@mathewi) January 1, 2014

For example, here’s one of Wendig’s 10 resolutions for 2014: “I will give my work the time it needs.”

Oh.

Better do that one again: ”I will give my work the time it needs.”

Wow.

Sometimes a story comes out fast. Sometimes it comes out slow…Overnight successes never are; what you see is just the iceberg’s peak poking out of the slush. This takes time. From ideation to action. From writing one junk novel to a worse novel to a better one to the ninth one that’s actually worth a good goddamn. From writing to rewriting to editing to copyediting. Don’t “just click publish.”

He’s not only talking to self-publishers, either:

Don’t just send it off half-baked to some editor or agent — they get hundreds of stories a day that are the narrative equivalent to a sloppy equine miscarriage or half-eaten ham salad sandwich…Take pride in what you do. Go the distance and get shit done. Not just a little bit done, but all-the-way-to-the-awesome-end done.

There are several more resolutions here well worth all our attention. I’m excerpting his comments about them. I suggest you read his full text.

Une bonne résolution pour 2014? Par Hervé Bienvault (@Aldus2006) http://t.co/cvxOz0y1UU

— Jose Afonso Furtado (@jafurtado) January 1, 2014

“I will earn my audience”:

You don’t build an audience like it’s a fucking chair. And you don’t beat your potential audience about the head and neck with that goddamn chair, either. You earn them by being the best version of you. You earn them by being passionate and awesome and not-an-asshole.

“I will respect the role of storyteller”:

Storytelling is news, entertainment, myth, religion, memory. As humans, we’re biologically a turbid broth of genetics — but intellectually, we’re stitched of a complex quilt of storytelling memetics. Other people won’t respect your role. They think what you’re doing is a half-a-jar of horseshit. But being a storyteller? Choosing to do this thing? It matters. Stories make the world go around. Respect the role, and your choice of it. Storytellers matter.

I've decided that for 2014, I'm going to review every book I read on Amazon & Goodreads. How's that for a resolution?

— Troy Blackford (@TBlackford3) January 2, 2014

This next one I find especially interesting. As the biz drives more and more decisions and detours, have you seen that blank look on some writers’ faces when they talk about their work? I have, too. Here’s Wendig:

“I will get excited about what I’m writing”:

What you do is you find a way to be excited about the work. You still make it yours. You own it. You claim it with the flag of your voice thrust into the earth of the work….Discover your own door into the material. Find the You-shaped hole in every story…Get geeked about your story. Write what thrills you. Every day of writing, sit down and ask: what am I going to write that excites me today?

as the tradition goes, if you write your new year's resolution on a yellowed Sheraton notepad, it will come true.

— Jen Doll (@thisisjendoll) December 31, 2013

As I said, Wendig does include what he terms “the simplest commandment of them all: write:

Write a little or a lot every day but goddamnit, write. Whether it’s 350 words or 3500 — the only way out is through.

Setting a daily word quota can help you keep your writing promises. @mariamurnane explains: http://t.co/PVlFiF99sF

— CreateSpace (@CreateSpace) December 31, 2013

But what sticks with me from his piece, like what sticks with me from good Dickens, is the focus he’s putting on what it is you’re writing and how it stacks up to the means, the modes, the digital machine we’re all feeding in one way or another:

You will succeed in the long run based on how you write and on the stories you tell, not on what method of publishing you choose.

What do you think? Even while being chased around the coffee table by digital in 2014, can we restore some emphasis on what’s being written?—and a little less on how many words damn it?

2014 seems like a good year to go back to bed.

— Don Linn (@DonLinn) January 1, 2014

Main image – iStockphoto: HeroOfTheDay2441

The post New Year’s Restitutions | Writing on the Ether appeared first on Jane Friedman and was written by Porter Anderson / @Porter_Anderson.

December 27, 2013

6 Ways Micro-Publishing Strengthens Your Author Career

Today’s guest post is by author Christina Katz (@thewritermama), who recently released Permission Granted, 45 Reasons to Micro-Publish.

For writers—especially nonfiction writers—a well-lit publishing-path through the murky wood of pundits, doomsdayers, and bestseller advice is micro-publishing.

Micro-publishing is not new, but when I use the term, I am referring to both the size of my publishing “house” and the length of my publications. In other words, micro-published books are short, tight, and swift. Experienced authors can deliver them in a steady flow, which can be less demanding and taxing than what it takes to create full-length books.

Micro-pubs vary widely in genre, format, and price point. (And fiction writers might consider serialization to be a better description of their micro-publishing landscape.) Micro-pubs with enough demand can become physical books eventually, usually when there is existing readership or demand for physical copies.

A meaningful discussion of micro-publishing has been pushed aside during the ongoing tug-of-war between traditional publishing and independent publishing (self-publishing). But we are well beyond “everyone is a writer” at this point. We have progressed into “everyone is a publisher,” if they wish to be—and we have been living in this realm for some time already.

Fortunately, micro-publishing benefits the industry as a whole by bringing some much-needed simplicity and directness into a publishing equation that is often weighted down by its own complexity and contracts. And it also benefits you, the writer. Here’s how.

1. Writers need to write. The changes in publishing have made contracts increasingly harder to come by, and advance rates lower, even when contracts do come. Micro-publishing allows you to keep writing and publishing no matter what the economy or the industry decide to do next.

2. Writers need to earn. Micro-publishing provides you with opportunities to earn passive income—and with less money flowing from publishers to writers, you’ll want to develop multiple alternative sources of income.

3. Writers need more ways to channel their ideas. Not every idea you have will be suitable for a traditionally published book. (Most aren’t.) But micro-publishing allows you to string together your better ideas and publish them in ways that benefit your readers. So micro-publishing gives you access to a series of smaller successes, rather than always investing the most energy in fewer, larger projects.

4. Writers often want to diversify. There is a lot of pressure on writers not to diversify—to keep delivering the same type of work to a ready audience. But some writers can handle diversification and would like to attempt it more often. Micro-publishing allows you to diversify on a smaller scale with less risk involved.

5. Writers who dive deeper into their niches can achieve increased readership loyalty. Readers don’t always like to wait a one or two years for the next book. And writers sometimes need relief from the pressure of too many publishing deadlines in a row. Micro-publishing can serve readers’ needs sooner and more swiftly than traditional publishing.

6. Writers grow skills from increased ownership. I got published in the first place because I produced my own career success. But once I started self-publishing some of my shorter works, that’s when I understood on a whole new level how much work publishers actually do. Can I do everything for myself that a traditional publisher can do for me? No. But I can learn valuable skills from increasing my career ownership and then take those increased skills back to the negotiating table with publishers down the road.

With all the editorial talent now available for hire, experienced authors can micro-publish more easily and more professionally than ever before. But it also offers a worthwhile option for writers who have never published because it’s a closer target and easier to hit.

But even writers who micro-publish won’t likely stop working with traditional publishers all together. Each form of publishing has a time, place, and benefit associated with it. More and more writers will take their careers into their own hands, rather than waiting to see what publishing decides to do next.

After all, when we talk about “publishing” today, we are no longer talking about a specific industry with gatekeepers. We are talking about a process that is accessible to all.

The post 6 Ways Micro-Publishing Strengthens Your Author Career appeared first on Jane Friedman and was written by Christina Katz.

December 26, 2013

Men Don’t Read Fiction? BULL! – Writing on the Ether

Table of Contents

I’ll Hold the Door for You if You’ll Leave That Baggage Behind

BULL Men’s Fiction: Heartbreaking Pants

They Read It. You Can, Too.

“I’ll Get in This Space”

I’ll Hold the Door for You if You’ll Leave That Baggage Behind

Here’s the last Ether of 2013.

I heard that sigh of relief.

As the gas escapes, I’d like to try the reverse of a new year resolution: instead of resolving to do something, I’d like to see folks resolve not to do it—or say it—ever again.

If I could choose one and only one publishing industry myth to leave behind in 2013, it would be the one that says men don’t read fiction.

And I have a response to that old scribe’s tale for you.

Before I tell you more about BULL Men’s Fiction, let’s look at what’s wrong with saying men don’t read fiction, and even simply men don’t read.

These lines are pernicious in at least two ways: one is business-related, the other is culturally important.

(1) In business. We need men to read more.

(1) In business. We need men to read more.

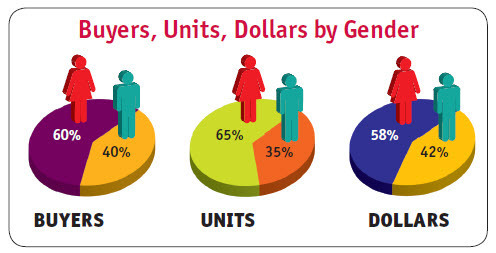

As our good colleagues at Bowker’s Market Research team (now owned by Nielsen) told us in the 2013 U.S. Book Consumer Demographics & Buying Behaviors Annual Review, the responses of women surveyed suggest that they out-buy men in books, and this trend might be rising.

From the report:

Women accounted for 58% of book spending in 2012, up over 55% in 2011.

That’s the spending metric. In terms of unit sales, the trend holds but did show a brief dip in 2011:

In 2011, women accounted for 57% of book buyers, which was actually a drop from 2010, when women accounted for 58% of book buyers. These numbers are up in 2012, with women accounting for 60% of book buyers. Women also bought more books, and spent more money on books, in 2012. In 2011 women accounted for 62% of units sold, whereas in 2012 they accounted for 65%.

From Bowker’s 2013 U.S. Book Consumer Demographics and Buying Behaviors Annual Review. BookConsumer.com/store

(2) In culture. Almost anyone you hear chanting men don’t read fiction will tell you that he or she wants men to read fiction. The line is normally delivered in tones that run somewhere between sorrow and anger, between regret and derision.

Ironically, saying men don’t read fiction in any tone is an incredibly bad way to encourage men to read. Each time someone says men don’t read fiction, you can almost hear a book snapping shut.

This is especially true if you say it around younger men who are still finding their masculinities. They’re naturally sensitive to our hyper-sexualized society’s fondness of “guys do this and women do that” nonsense. They’re eager not to do anything outside “what guys do.” Any suggestion that “what guys do” doesn’t include reading fiction (or reading at all) makes it much harder for them to get back to that book again.

Books, fiction or nonfiction, are not innately pink. Turning them that color by pushing around such a chestnut as men don’t read fiction—a line that implies that only women read fiction and that reading is for girls—can profoundly derail what might have been a guy’s healthy habit and enjoyment of buying and reading literature.

Those earlier years have expanded for many American men, of course, in the construct laid out by Stony Brook University Prof. Michael Kimmel, who heads up the school’s new Center for the Study of Men and Masculinities.

Those earlier years have expanded for many American men, of course, in the construct laid out by Stony Brook University Prof. Michael Kimmel, who heads up the school’s new Center for the Study of Men and Masculinities.

In Guyland: The Perilous World Where Boys Become Men, Kimmel has described a delayed entry into male adulthood that’s endemic in our culture and hardly conducive to inspiring bookish interests among fellows who are told that reading is for girls.

Kimmel writes:

Guyland is the world in which young men live. It is both a stage of life, a liminal undefined time span between adolescence and adulthood that can often stretch for a decade or more, and a place, or, rather, a bunch of places where guys gather to be guys with each other, unhassled by the demands of parents, girlfriends, jobs, kids, and the other nuisances of adult life. In this topsy-turvy, Peter-Pan mindset, young men shirk the responsibilities of adulthood and remain fixated on the trappings of boyhood, while the boys they still are struggle heroically to prove that they are real men despite all evidence to the contrary.

Guyland sounds like a place in which a man could sure use a good book, doesn’t it? But no wonder the Bowker study shows men’s spending on books not picking up until the guys are out of their twenties:

The age groups where men spent the most money was in the 30 to 44 year-old group at 46% and in the 65 and up group where men accounted for 45% of spending.

It’s my belief—based entirely on my own experience and backed up by not one whit of evidence I can produce for you—that the best thing to happen to men’s reading is the advent of ebooks.

On a Kindle Fire or a Kobo Aura or an iPad or phone or any number of other screens, you can’t tell what a guy is reading. I think guys like it that way. I know I do: it’s none of your business what I’m reading. I think that for the most part, men are less demonstrative than women about their reading. And without some honking dust cover on the plane, for example, our guy can tell his company associate in the next seat that he’s reading the PDFs from the office on that Kindle. And go on with his Alissa Nutting.

Honestly, I’m not sure guys even tell survey takers as much about their reading or buying habits as the researchers might wish. It’s none of their business, either, you know?

Do you keep a record of who recommended which books to you? If you did, you could put together such irritating lists as this one: men have recommended to me in the last six months that I read the following fiction:

John le Carré’s A Delicate Truth;

James Salter’s All That Is;

David Gerrold’s The Man Who Folded Himself;

Evie Wyld’s All the Birds, Singing (a Costa short-lister that’s not listed to publish in the US until April and boy, is that annoying, Pantheon—the Brits are reading it, why aren’t we?):

Christine Sneed’s Little Known Facts;

Hugh Howey’s The Plagiarist;

Andy Weir’s The Martian;

Eleanor Catton’s The Luminaries; and

Jason Matthews’ Red Sparrow.

Isn’t that a remarkable thing?

Because men don’t read fiction. Everybody knows that.

And yet they’re making recommendations to each other based on all that reading they don’t do.

Alan Turing was granted a Pardon today. Ironic, as it's his forgiveness this country should have sought years ago. pic.twitter.com/FgcU9n6zKh

— Jonny Geller (@JonnyGeller) December 24, 2013

Guys are telling other guys right now about Howey’s Sand—which, of course, they haven’t read because men don’t read fiction—even as it rolls out in installments; even as Howey’s own descriptive note on the first part suggests waiting until the full book is published in a single unit; and even though people are telling them that men don’t read fiction.

Wait a minute.

Wait a minute.

A guy just told you about Sand. And men don’t read fiction. It’s a fin de 2013 publishing crisis for the industry! the industry! Let’s get badly and pointlessly upset, as only we publishing people can do, and hurl screaming blog posts at each other about it, shall we?

No, no, better yet, this: what I want you to say, the next time you hear someone intone, men don’t read fiction?—BULL.

If the Internet had been around when I was little, I would have sat and watched Santa Tracker all night until I fell asleep on the keyboard.

— Ginger Clark (@Ginger_Clark) December 25, 2013

BULL Men’s Fiction: Heartbreaking Pants

Jarrett Haley

“In 2009, I’d just finished a graduate program at Notre Dame, and all my friends took off.”

The friendless Jarrett Haley, founder and editor of BULL Men’s Fiction, had a wife pregnant with their first child. “I was going to be staying home taking care of the baby, and I knew that without some outlet to talk to writers and work on things, I’d go crazy. I wanted to keep in contact with writers.

“I thought about what I’d want to work on,” Haley says. “We were hearing the same things about publishing. ‘Men don’t read,’ blah, blah, blah—I was sick of it. I wanted to do something that was progressive, you know?”

“That’s when I came up with the idea of men’s fiction. There was an opportunity there. Once the notion hit me, I thought of it as a project, an experiment—what would I get when I put out the call for ‘men’s fiction,’ quote-unquote?”

The BULL Men’s Fiction site, 2009-2010

Maybe not the tech-savviest among us, writer-dad Haley first put together “a rudimentary Web site” that carried along the idea at ground level for a couple of years. As soon as the fledgling site “got a little traction, we got to a point,” Haley says, “where we had to decide, ‘Well, are we doing to do this or not do it?’”

And what encouraged Haley to stick with it was pants: a Dockers “Wear the Pants” competition for a $100,000 national campaign. The idea was to formulate a goal and a plan to achieve it; become one of five finalists chosen by a panel of judges; and then to win the popular vote on Facebook.

“We almost got it, we got second place,” Haley says. “It was so heartbreaking, man. The guy who won was some college kid with a huge online network.”

A Dockers ad, from a NY Daily News article

As it happens, Dockers’ “Wear the Pants” advertising copy is some of the best Guyland/Kimmel-esque material you may read today.

In this instance, for example, you read, in part:

Disco by disco, latte by foamy non-fat latte, men were stripped of their khakis and left stranded on the road between boyhood and androgyny…For the first time since bad guys, we need heroes. We need grown-ups.

Haley says the competition experience “gave us enough momentum to say, ‘OK, let’s do this thing for real.’”

So after that, we got a new Web site, and we’ve been doing print issues” of BULL Men’s Fiction “for about two years. With this second version of the site, I think we’ve really just started to come into our own. At each point, it gets a little more polished.

Haley is a native of Clearwater, Florida. He went to the University of Florida, then to Notre Dame’s MFA program, and recently has moved with his wife and three children to San Diego. The oldest of the kids is 4 years old. His wife has family in San Diego.

“We can use the help.”

BULL Men’s Fiction site, 2011-2012

They Read It. You Can, Too.

BULL Men’s Fiction is a newly relaunched site (just this month) and a print magazine, about 130 pages, published twice a year.

A lot of us would say walks like a journal and talks like a journal. Don’t tell Haley that. He’s not fond of calling it literary, either.

I want the quality of a journal, but the fun and style of a magazine. I don’t want to bash anything but there are pros and cons to both of them. I don’t want to call it a ‘literary journal.’ I think it’s a turnoff, honestly. We’re marketing ourselves to regular guys. ‘Literary’ sounds like homework, sounds like something they aren’t attracted to. So I go with ‘fiction magazine,’ because that’s really what it is.

BULL Men’s Fiction, the relaunched 2013 site

Haley heads a staff of close to 20 people who are working on BULL. They’re all over the country. They’re unpaid.

You subscribe for $20 per year. You can also buy back issues. Here’s the store.

The site has a wide range of BULL writers’ work sampled free in its archive. Most of those are truncated articles, not full-length. Haley would rather tempt you to subscribe with these samples than put the thing behind a pay wall.

“I really don’t like paid Web sites,” Haley says, while conceding that his next step is to get into digital delivery channels, such as a subscription edition for Amazon’s Kindle Magazines.

“I’m trying to make the operation as streamlined as possible,” he says. “It has to be as low-maintenance as possible and as fun as possible” to keep his team engaged and pulling together. “We never could have done what we’re doing now without this staff.”

Learning about the wines of Catalonia. The reds are extradinorartiately good.

— Don Linn (@DonLinn) December 25, 2013

“I’ll Get in This Space”

Members of the BULL Men’s Fiction staff include, from left, Tim Chilcote, Senior Editor; Jared Yates Sexton, Managing Editor; Michael Goodell, Editorial Board member.

“What we’re doing” at BULL Men’s Fiction, it turns out, involves presenting new fiction by writers including National Book Award nominee Padgett Powell; Canadian bassist and writer Chris Tarry; McSweeney’s John Warner.

There’s also a “Prison Book Review” series of pieces by Curtis Dawkins, an MFA graduate from Western Michigan University who writes about books and the incarcerated life from the Michigan Reformatory in Ionia.

And each print issue is led by Haley’s interview of an author. His past subjects have been Chuck Klosterman (The Visible Man, Scribner) and Donald Ray Pollack (The Devil All the Time, Anchor).

Most recently, Haley writes up Allan Gurganus, whose trio of novellas, Local Souls, was released by W.W. Norton’s Liveright in September.

In an era in which many in publishing talk about almost nothing but the business and its struggles in the digital transition, the Haley interviews frequently change that tune by talking about the work, itself.

In his interview with Gurganus, Haley runs a line from Local Souls past the author and develops a point about fathers and their sacrifices to achieve types of success that their children may not recognize. Haley asks about:

In his interview with Gurganus, Haley runs a line from Local Souls past the author and develops a point about fathers and their sacrifices to achieve types of success that their children may not recognize. Haley asks about:

When the narrator is describing the fancy house that his father coveted, then finally attained, he says, “It had been Red’s great wish for himself, meaning me.” Can I ask you…what that line means to you?

Gurganus responds with insight about parents’ projection on to their kids an idea of success they can’t gain for themselves.

I think Red seems his son as his own best self. He feels that by making an easier life possible for the son, he is in fact redeeming and immortalizing himself.

As the conversation develops, you learn that the underlying concept of personal unworthiness that suffuses such misperceptions by parents of their children’s eventual interests, is behind Gurganus’ name for the setting.

I named the town Falls after the fall of man. The townspeople call themselves the Fallen instead of the Falls-ites. It’s a kind of play on our fore-parents’ having eaten of the fruit of the knowledge between good and evil. We are all living post-Eden but struggling, that’s for sure.

There are cases in which Haley has cultivated a writer’s interest and wants to make a payment from the magazine’s limited funds. Articles that come in over the transom, however, if used, aren’t usually paid at this point.

Three editions of the print magazine have come out so far.

The “Trouble Issue” is next in the spring, following the “Humor Issue” and the “Improvement Issue.”

The magazine has about 200 subscribers.

Over time, a single issue will sell some 1,500 copies.

Writer-dad Jarrett Haley

This is small and it’s early, but the potential of the operation shows in the curation of material and the consistency of presentation. There are better established poetry and prose publications in the journal world selling at this level; these numbers are not bad for an outfit the staff of which has no PR or advertising person.

Ball and Buck (“presenting the last belt you’ll ever buy”) has become an advertiser, taking the back cover of the latest edition of the print magazine. The hookup there happened in Boston, where Haley and his staffers had a BULL party during the AWP Conference there earlier this year.

And when Haley tried a typical call for submissions, he says, using the NewPages.com platform, he found that the transom may not be the right channel for what he’s doing.

“It really didn’t feel good,” he says.

They were deluged with material. “It felt like people saw the ad, went straight to ‘submit’ and just wanted to throw their stuff at us. What I really like is hearing from people who like what we do” and want to develop a relationship with the magazine.

“After all, that’s where it started for me,” he says. “It was me wanting to meet people” who are writing. “We give feedback, we make an effort to really reach out.”

He’s torn on the question of calls for submissions, though, he says, having had encouraging response from editors at Playboy once, when he submitted a piece. “I wanted a place like Playboy, where I could send something and somebody might read it.”

BULL Men’s Fiction has published women as well as men. “We don’t get many submissions from women,” Haley says, but the first print edition includes a story, “Houseboy,” by Sara Lippmann, that’s “one of my favorite pieces of everything we’ve run, it’s really, really good.”

And in an industry that’s better at times at reciting assumptions than addressing them—men don’t read fiction—push-back can come in the form of a fledgling semi-annual magazine gamely finding its footing in persistent focus, non-combative but also unapologetic.

“I said, ‘Well, no one’s in this space, so I’ll get in this space.’”

[image error]

This quote from CS Lewis’ “The Four Loves” drew 17,142 likes on Goodreads in 2013. Courtesy: Suzanne Skyvara

Main image – iStockphoto: Oleh Slobodeniuk

The post Men Don’t Read Fiction? BULL! – Writing on the Ether appeared first on Jane Friedman and was written by Porter Anderson.

December 20, 2013

How Much Does Author Platform Impact Sales?

by Lori Greig / Flickr

As most authors know by now, there is a continuing debate over the importance and impact of one’s platform on book sales.

In one of the more interesting experiments I’ve seen, author C.S. Lakin (@cslakin) decided to publish a genre novel (in a very particular genre, with a very particular formula) and release it under a pen name, to test whether a first-time author—one ostensibly without any platform—could sell a meaningful number of copies. Read her full post about it.

You can find a diversity of lessons in what Lakin did; one of the key takeaways (for me) relates to the role that genre plays in an author’s success in achieving e-book sales through the largest online retailer in the world, Amazon.

Lakin commented that her purpose wasn’t necessarily to prove platform unimportant, but the headline of the post and the comment thread (of course) point to a great deal of excitement over the early results: this first book by a platform-free author is selling 30-50 copies every day.

In January, I’m teaching a class on platform, which makes me look like a rather biased party on this topic. I’ve been teaching some version of it since 2009, and my ideas have evolved over the years. Some of that evolution can be traced through these posts:

A Definition of Author Platform

Should You Focus on Your Writing or Your Platform?

The Art and Business of Reader Engagement & Author Platform

In a nutshell, I tend to agree with those who advise that fiction writers put a low priority on platform building, at least until you have some books to market and real seriousness of intent. By seriousness, I mean: you expect to earn money that will help provide a living. But I also believe that paying even a little bit of attention to developing direct connections with readers (e.g., through having your own website) pays off over the long-term of your career. You don’t do it for short-term gain; you do it to incrementally grow your name recognition and spread word of mouth—to help you better discover and engage with readers over 5, 10, or 20+ years. (Some might not even categorize this activity as platform building, but the word has become very fuzzy in publishing circles over the years, and functions as a blanket term covering sales, marketing, promotion, publicity, and branding.)

Here’s the thing about Lakin’s experiment. I think it reveals platform hard at work, because Lakin happens to have a solid platform she can’t hide, even with a pen name. Let me explain.

As far as my definition, I believe author platform has 6 key components:

Your writing or your content (in this case, books)

Your social media or online community presence and outreach

Your website

Your relationships (people you know, the kind of people who will answer your e-mails or phone calls)

Your influence (e.g., your ability to get people you don’t know to help you out, listen, or pay attention)

Your actual reach (the number of people you can reliably broadcast a message to at any particular moment in time)

When people hear the word “platform,” they often think about social media, or doing self-promotional activities. What they forget is that one’s body of work is the entire engine behind any author’s platform—it all starts with the writing and its appeal to a target audience—and also includes relationships developed in the process.

I haven’t spoken to Lakin about this (I may set up an interview!), but just looking at the surface of her experiment, here’s what I see happening.

Social media outreach: Lakin used her own Twitter account, which has 44,000+ followers, to spread the word about the book.

Writing & content: Lakin is the author of more than a dozen other books. When she tweeted about her new book, she was appealing to people who already know and like her—and people who could help spread the word. (That said, I understand that perhaps her current fans may not be active readers of the genre in which she now writes under a pen name.)

Relationships: Lakin appealed to well-known author friends to write reviews of her work, which presumably offered social proof and credibility to her debut book. But how many authors without a platform have such relationships already in place?

There are other helpful factors, which some may not categorize as platform—and perhaps much of this truly boils down to our definitions of that word!—but that I find at least related to the strength of your platform. Lakin was having conversations with people about which genre to choose and was conducting some amount of reconnaissance—presumably drawing on relationships that are always part of any author’s long-term success. And she is now discussing the experiment at one of the biggest blogs for self-publishing.

None of this is to downplay the value in Lakin’s experiment and what lessons it holds for authors looking for keys to success. The most important point she makes (IMHO) is not to be taken lightly: the genre/subgenre you write in (or at least categorize your book by) affects success—and can carry a book’s sales, at least in the short term—if you’re following the conventions of the genre and playing well with Amazon. I just wouldn’t be so quick to say, “This was a book published without an author platform,” when we’re looking at someone who is very experienced in the industry and has a network of valuable resources to draw upon.

The post How Much Does Author Platform Impact Sales? appeared first on Jane Friedman and was written by Jane Friedman.

December 19, 2013

Writing on the Ether: When the Wise Women Get Here

Table of Contents

They Three Queens of Orient Were

Hope and Fear #1: Visibility

Hope and Fear #2: Literary Fiction

Hope and Fear #3: Rest

They Three Queens of Orient Were

If they’d been guys, they’d never have made it to the Nativity. Once the OnStar of David navigation system got behind a few clouds and everybody got disOriented, only women would have stopped to ask for directions. And to do some shopping. Gold, frankincense, myrrh.

I concede that I’m unusual among your modern preachers’ kids. I’ve always had a high level of respect for the King James Version of the New Testament. Its rendition of self-publishing author Luke’s Executive Summary of Certain Events in Judea does us the favor of having the Angel of the Lord correctly avoid the grammatical pratfalls that would have decked a lesser emissary:

Ye shall find the babe wrapped in swaddling clothes, lying in a manger.

Catch that? “Lying in a manger.” So good.

The Angel of the Lord knew that Jesus was lying in a manger. Not laying in a manger. Mary laid him in a manger. And then he was lying in a manger. And that’s the last time anyone got those things right on Earth as it is in heaven.

And this shall be a sign unto us that the Angel of the Lord was an editor. Maybe still is an editor, although whose job description hasn’t changed five times since Bethlehem?

So while waiting for glad listicles of great joy—3 Ways To Tell Your Camel is a Baptist— I’ve decided that when the czarinas-on-tour finally get here, it’ll make sense for the writing community to ask for exchange receipts on those gifts.

Not that the gold isn’t tempting. But here near the close of 2013 (you can stop putting out book lists now, everyone), it would be good for the author corps in particular to ponder three things in its collective heart.

Not resolutions. We don’t do those on the Ether. We are irresolute here.

Not predictions, either. In this field, it’s all too rare to find a shepherd who can keep watch over the industry! the industry! and risk predictions without looking sheepish.

No, we can look to Phillips Brooks’ lyrics for “O Little Town of Bethlehem” for what we need:

The hopes and fears of all the years are met in thee tonight.

Instead of gold, frankincense, and myrrh, I’m asking for the hopes and fears of visibility, literary fiction, and rest.

If one more kid, writing an assigned "author report," asks me the stock question, "What inspires you to write?" I am going to scream.

— lois duncan (@duncanauthor) December 18, 2013

Hope and Fear #1: Visibility

“All this and more,” as we like to say in TV news, tomorrow at Publishing Perspectives, where I’ll be recounting some of what went on Wednesday in our #EtherIssue weekly Live Uproar on Twitter.

For our purposes here today, I want to call your attention to this:

RT @ljndawson: @pubperspectives 391,000 self-published titles in 2012. As my Xian family would say "sweet mother of God." #etherissue

— PubPerspectives (@pubperspectives) December 18, 2013

The information being imparted unto us by Bowker’s Shepherdess of the Identifiers, Laura Dawson, is both old and new.

We had heard that Bowker was able to track some 391,000 self-published ISBNs in 2012. And yes, as our @PubPerspectives associates noted, this figure, alone, does invoke memories of the deity’s mom, Bethlehem-based or otherwise.

Laura Dawson

What’s new is an interpretation of the Bowkerian data that indicates 2012′s activity reflected a 60-percent jump in ISBN usage by self-publishing authors over 2011. Got it? Sixty percent more authors procured and published with ISBNs than in the previous year. And that jump is—as we’ll discuss in Friday’s piece—despite some deep resistance to the ISBN (and its cost) among entrepreneurial authors, who are required to pay a lot more for their ISBNs than publishing companies pay for theirs (in bulk).

But there’s also a need for us to understand the scale of the self-publishing presence in publishing. Remember that if Bowker could count 391,000 self-published ISBNs (titles) in 2012, there were many, many more than that—precisely because we cannot “see” the titles published without such identifiers and because our great retailer/platforms (Amazon, Barnes & Noble) can’t find it in their corporate hearts to share their sales data with us.

The hope: that even more self-publishing authors will agree that being able to demonstrate the mounting power of their side of the industry is worth standing up and being counted.

The fear: that we’ll find out the market is severely more glutted with titles than we’ve guessed so far.

Hint: Bowker is not the enemy; incomplete data is.

FUN: Contemporary literary fiction has become so esoteric and obscurant, adults have turned to YA novels for actual, accessible emotion.

— Liam G. (@LHGarrett) December 18, 2013

Hope and Fear #2: Literary Fiction

James Scott Bell

So I jumped all over poor unsuspecting James Scott Bell the other day when, in First Be a Storyteller, he got off one of those casual references you read in blog post after post after post after post about…well, here, this is what my friend Jim wrote:

If I have to choose between a novel that has a “literary” style but a dull (and even, perhaps, a non-existent) plot, and a novel that has a killer concept and professional writing, I’ll go for the latter every time. While I can enjoy a bit of “style for style’s sake,” it can run out of steam quickly if that’s all there is. Indeed, I’ve read some highly lauded lit-fic that turned out to be, for me at least, the scribal equivalent of the emperor with no clothes.

In and of itself, that’s a perfectly fair opinion to have and to hold from this day forward. In truth? I, too, want actual story, momentum, and a point in books I read. Pointless is…pointless.

And once I’d unloaded a bit of frustration over this 8,944th iteration of the literary is lifeless recitative, I declined Jim’s kind offer to comment further, feeling that The Kill Zone (a blogging group of mystery and thriller writers) could do without more of my soapboxing on the matter.

Nevertheless, there’s an issue here. Self-publishing has tended so far to exacerbate this slagging o’ the literary, favoring other genre fiction and nonfiction. (Just think, if we had figures on self-publishing, we could actually tell how much literary there is as compared with other genre work. See #1.)

And I’m unsure why so many good, thinking, responsible folks seem to feel the need to get off these drive-by snipings at literary fiction on the way to other points and other shelves in the virtual bookstore.

If you only see one literary reference on a sign today, make it this one. pic.twitter.com/zvDGAZRJSq

— Scott Jordan Harris (@ScottFilmCritic) December 18, 2013

I’m not talking to my good friend Mr. Bell in the following little litany, I’m speaking to the multitude of the self-publishing, literary-lashing host:

Have you been bitten by a literary fiction writer? Did Michael Cunningham knock you down and steal your lunch? Then report that violence to me, I’ll deal with it for you.

Have you been personally snubbed by the literary fiction writers you claim are so holier than thou? Did Eleanor Catton say something ugly about your latest grocery list? I doubt it. I think the chip on your shoulder is of your own making and just may have to do with concerns about the caliber of your own output. Why such a concern? That’s between you and the kid who is lying, not laying, in that manger. But why not stop foisting it off on everyone else as if Sam Byers tossed a wad of dirt onto your living room carpet last week?

Have you never read a pulp fiction book that was so stupidly invested in being noir that you couldn’t see your hand in front of your face to throw it across the room? I have. Have you never read a science-fiction title so inanely fanciful that it was clear the author had yet to catch up with the technology behind the automatic ice maker in his own freezer? I have. Have you never read a Shirtless Men Kissing Beautiful Women title so pathetically cloying that you feared it had just set back the romance-reading population about 25 years in terms of personal relationship development? I have.

The hope: that more blogging writers will think twice before gratuitously slamming literary fiction as if it were sitting in judgment on everyone else.

The fear: that the digital dynamic will make literary fiction less commercially viable, as other fine-art elements of our culture have been eclipsed by…car chases. Digital, remember, is an energy of distribution. It seeks the widest and therefore least discerning audience in any and every entertainment medium, not just books. It’s enough for literary to contend with digital’s love of feel-good diversions without our helping it along by dissing it at every opportunity.

Hint: Many if not most literary novels do have plot, action, purpose, and drive. We could start by not lying, or laying, about that.

@samatlounge (c) Cocktails!

— Don Linn (@DonLinn) December 18, 2013

Hope and Fear #3: Rest

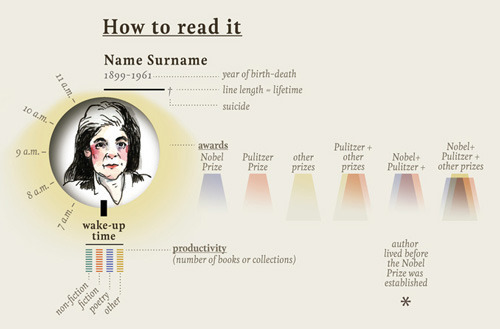

By Maria Popova, Accurat, and Wendy MacNaughton. BrainPickings.org

The infographic you see here is produced by our good colleague Maria Popova of Brain Pickings, and is a collaboration between her and several good folks including Georgia Lupi and Wendy MacNaughton.

In Famous Writers’ Sleep Habits vs. Literary Productivity, Visualized, Popova explains:

I found myself especially intrigued by successful writers’ sleep habits — after all, it’s been argued that “sleep is the best (and easiest) creative aphrodisiac” and science tells us that it impacts everything from our moods to our brain development to our every waking moment. I found myself wondering whether there might be a correlation between sleep habits and literary productivity.

Now, here’s a line that could make a publishing-community member burst into tears:

The challenge, of course, is that data on each of these variables is hard to find, hard to quantify, or both.

Nevertheless, Popova and her associates have succeeded in fashioning an entertaining look at what are believed to be the wake-up times for various authors and have coupled that with color-coded references to their productivity (number of works published and awards “garnered,” as no one ever says in real life).

Honoré de Balzac, of course, leads this awakening chorus with his famous 1 a.m. stagger out of bed. That’s something the aforementioned James Scott Bell and I have discussed with caffeinated zeal many times. Balzac was, as are we, a devoté of the bean, which may have contributed to his undoing at age 51 in 1850.

The 4 a.m. team on Popova’s chart is anchored by Murakami and Plath.

Mr. Healthy, Wealthy, and Wise, Ben Franklin, apparently didn’t roll out until a comparatively cushy 5 a.m. and today could have had his java at that hour with Toni Morrison.

Maria Popova

Get to the other end of the chart and you’ll find that slacker Charles Bukowski, bed-headed at noon.

Popova’s effort is a fun consideration that leads us, here in the close-gathered mists (4:54 a.m. as I write this) with a couple of more serious digital-era considerations that bothered few of the souls cited by the Picked Brain (I did not say Pickled).

Many of us are struggling to get enough rest. If electrification gave us the chance and then the imperative to work at night, digitization has thrust upon us the privilege and then the burden of being always on.

Digital in its purer forms is never off. As that engine and energy of distribution I’ve talked about, for example, digital is what makes it feasible for your mother’s latest cat video or that picture of your darling child (yet again) to be viewed at all hours, in all parts of the world online.

And this reality of productive potential is working on many of us in ways none too good for literature.

BrainPickings.org

The digital dynamic is damaging some, not all, literature because so many people are telling writers to turn more copy faster. The current marketing mantra for authors is to write more books, write them faster, stack them up high on the Net so readers will stay with you: “Oh, goody, another book I haven’t read by this author, perfect.”

In the purest marketing context, yes, this makes good sense. You hold them with inventory. “You liked that one? You’ll love this one.”

But maybe they won’t love it. Because maybe you’re getting tired, careless, harried.

I’ve just watched a very good book go out too early, and it didn’t have to. It had a chance of being great. But that temptation to publish is too much for a lot of folks, and ironically it may be most seductive to the ones who have suffered the unforgivably slow processes of traditional publishing before turning to the always-on mechanisms of digital self-publishing.

The push for series, even for multiple series; the pressure to put out more books faster; the emphasis you see in so many how-to posts on word counts; frequent whip-cracking admonishment to keep writing, grab every moment, bang away at it, do a writing sprint, spree, binge, jam…all this is rarely intercut with those quieter questions: “Yes, but do you have anything to say at the moment? Was there a point to that book you’re writing? Why did you want to write before you wrote?—can you remember?”

C.S. Lakin

The idea of simply choosing a niche that has less competition in it than others was featured in a guest post at Joel Friedlander’s site this week, C.S. Lakin writing about an experiment she had made in Genre Versus Author Platform? Which Matters More? She tried creating a title in the “sweet” historical western romance subgenre. (“No sex or heat,” as she explains it.)

Be careful to note Lakin’s own disclaimer:

I don’t think writers should “sell out” and write something they don’t want to write just to make money, but hopefully I’ve given you food for thought. I find nothing wrong with writing to a specific audience for the sole reason of selling more books and making some money. It feels nice to pay the bills.

There will always be mercenaries among us, yes. And some of them certainly will have talent. Fewer may be as thoughtful and as forthright as Lakin is. She’s confirming that there’s a place for pure entertainment. Digital is making that a place as wide as a sweet romantic cowboy’s plain, too.

Many more may be in the boat(s) mentioned by Jessica Bennett of the reader-enthusiasm site Compulsion Reads in a post at Writer Unboxed on the first anniversary of her outfit. In Ten Things I’ve Learned From Evaluating Self-Published Books for a Year, Bennett writes of how “self-published authors need to care more about grammar,” and she adds that these writers “struggle with making big edits to their books,” the latter being something I’d bet most writers struggle with.

Many more may be in the boat(s) mentioned by Jessica Bennett of the reader-enthusiasm site Compulsion Reads in a post at Writer Unboxed on the first anniversary of her outfit. In Ten Things I’ve Learned From Evaluating Self-Published Books for a Year, Bennett writes of how “self-published authors need to care more about grammar,” and she adds that these writers “struggle with making big edits to their books,” the latter being something I’d bet most writers struggle with.

The systemic issues Bennett spots may well be influenced by the hurry-up-so-you-can-hurry-up-some-more ethos. For most writers whose impetus comes from a desire to say something through their work—and I hope and fear you’re one of them—churning it out may prove to be early-days overreaction, overwork, overwriting amid the technical capabilities of digital.

The hope: that in 2014 we all can make rest a bigger part of sorting out what it is we’re doing, not just dump it onto the market fast…just because we can.

The fear: that you’ll need to be rested not only to better evaluate the work you’re doing but also to tell off people when they demand to know “what’s taking you so long?”

Hint: You rest up and sort out how your stuff is lying on the page and the lay of your career. We’ll wait for you. We already have plenty to read, thanks.

I could do with a lie-down, not lay-down, myself. Wake me up when the three you-know-who’s get here. I’m very fond of camels.

My favourite correction of 2013 pic.twitter.com/uZ0QRfY4Kd

— Jonny Geller (@JonnyGeller) December 18, 2013

Main image iStockphoto: Andrew Soundarajan

The post Writing on the Ether: When the Wise Women Get Here appeared first on Jane Friedman and was written by Porter Anderson.

December 13, 2013

The Art and Business of Reader Engagement and Author Platform

by crises_crs / via Flickr

Note from Jane: In January, for the first time, I’m teaching an online-based course on developing your author platform. I’ve taught this many times at writing conferences, but have yet to offer the curriculum in an online environment. Click here for more details about the course. It offers a lot of perks, including a website or blog critique from me.

In the nonprofit world, you’ll frequently hear about “audience development,” which concerns itself with outreach to people interested in what you do, and customizing that outreach based on a person’s level of interest.

Audience development is difficult to strictly define because it involves not just pure marketing, but one-on-one relationships. It’s not about selling (although the result is often sales); it’s about creating an experience or community that engages with you over the long term. And that requires that you communicate with your readers meaningfully and consistently.

One of the best summaries of audience development I’ve read is from Shoshana Fanizza, who has spent more than a decade in arts development:

Audience Development, in a nutshell, is all about relationship building to achieve the “power of people” to support your art form. Consider it as building positive energy, people energy, to attract more support for you. Audience development does take time to see results. It is a building process. … You want to get to know your audience and connect with them. If they feel connected and cared for, they will want to become more involved. It will take effort and persistence, but you will see the relationships you build start to form a positive community around your art. This community is the key to succeeding!

So, audience development is a fancy business word for directly communicating with your readership, and engaging with them in a way that’s mutually beneficial and respectful. What follows is a starting framework and strategy for doing just that, and much of it overlaps with developing your platform. (If you don’t know what platform is, read my definition here.)

Why is this important?

You should take full ownership of reader engagement because it represents an investment in your lifelong career as an author. Don’t rely on a publisher, agent, or consultant to find and “keep” your audience for you. If you find and nurture it on platforms and channels that you own, that’s like putting money in the bank.

Part One: The Art and the Authenticity

When new authors ask me if they can just hire someone to engage with readers (e.g., on social media or elsewhere), they’re often missing the point and the benefit of communicating with readers. Learning about readers directly and strengthening the connection leads to better marketing and promotion in the long term. When done well, it requires that you be present and be authentic. It’s tough to do that if someone else is pretending to be you—and it can also prevent you from gaining insights into how to improve your future work. For example, many of the blog posts I write here, or fully reported pieces I produce, are a direct result of questions and conversations I have with writers on social media or writers I meet at conferences.

However you decide to directly communicate with readers, it’s important that:

You enjoy the tools or platforms—so you stick with them for the long haul (plus readers can tell if you’re not enjoying yourself).

You’re consistent with your voice and style, and that you don’t adopt a “marketing voice” that might be a turn off to readers.

You focus on what’s satisfying and engaging for both you and readers.

People often respond well to playfulness, or when you’re not taking yourself too seriously. This isn’t to say you can’t or shouldn’t discuss serious issues. Rather, it means you’re not afraid to experiment, have fun, and be human. Not to get too psychological, but knowing yourself and feeling secure about who you are (and what you are not) goes a long way toward successful communication with your audience. (This is true for any business or organization as well.)

Part Two: The Business

First things first: However and whenever you engage with readers, it should be on a permission basis. That means the reader has already indicated they want to hear from you—by liking you, following you, signing up for e-mails from you, etc. Based on the level of interest expressed, behave accordingly. For instance, how you behave and communicate with Twitter followers should be different than how you communicate with long-time subscribers of your e-mail newsletter.

Your communications will usually have 1 of 2 objectives:

Sales-focused, e.g., book-launch announcements

Relationship-focused (platform and audience development)

Sales-focused communications are typically tied to specific marketing campaigns, book launches, or other strategic initiatives when you’re measuring their effectiveness and impact. (If they’re not, consider why you’re sending out sales messages without a strategy in place.)

For the purposes of this article, I’m focused on relationship-focused communication (which often impacts the success of your sales communication). A few of the most critical tools include the following.

1. Your own website + Google Analytics. Your website is one of the best tools you have when making first contact with existing readers. You can use it to capture and communicate with your audience on a career-long basis through a blog or an e-mail newsletter, and you can analyze how people find you, what affects people’s interest in you (and how/when they spread the word about your work), and what content is most popular with readers.

How do you find all this out? Both Google Analytics and e-mail newsletter analytics (more on e-newsletters next) will tell you a very pointed story about what your readers are looking for and what keeps their interest. You can uncover whether or not your social media accounts are having any impact on spreading the word (building buzz), and you’ll learn what keywords people search for that land them on your content. This kind of data is invaluable when making hard choices about where to spend your time communicating with readers (especially when you need to focus on writing), what readers value in the relationship, and what they want to see more of.

Look at your website today, and ensure you’re giving visitors an action step. What is it you want them to do when they arrive? Should they sign up for your e-newsletter? Should they get a free download? Should they follow you on Facebook or Twitter? If you’re not prompting visitors to act, they probably won’t.

2. E-mail newsletter. E-mail is not dead. It is still one of the most effective marketing techniques available anywhere, to anyone. And for authors, it allows you to communicate reliably and directly with your audience from one book to the next. You own the e-mail list, and you want the power of direct engagement with your readers without the danger of websites folding, platforms changing, or publishers merging.

Therefore, on your website (and anywhere else where it makes sense: Facebook fan page, writing conference engagements, etc): Ask people to sign-up for your e-mail newsletter. MailChimp is an excellent e-mail newsletter provider to use, free up to 2,000 names.

There are different types of content strategies for the e-mail newsletter; some authors only e-mail their readers one or two times a year, with a brief news summary or updates about new releases. Others e-mail more frequently and take time to send out useful content. For example, author C.J. Lyons interviews an author and includes the Q&A in the newsletters she sends.

I prefer the useful content strategy, but whatever strategy you choose, don’t let your list languish without making contact at least one or two times per year. Otherwise, people will forget they signed up, mark you as spam, and your efforts will have been in vain.

3. Social media sites or online communities that your readers frequent. Hopefully there is a sweet spot between:

What social media or online communities you enjoy

Where your readers reliably gather and communicate

What mediums naturally complement your work

I advise experimentation until you figure out which sites or communities carry the most meaning and impact for reader communication (using analytics to help you determine the best choices). Once you identify which channel is effective for you, the big question becomes: What do you do there? Well, it’s not about blasting buy-this information. To be an interesting person, you have to be interested in the world, and in other people. You have to be curious. So find ways to post and share about things that fascinate you or puzzle you. Post questions for other people to answer. Ask people to share something. You may not get it right at first, but remember: playfulness helps.

4. Customized communication and experiences. The people you reach (online or off) will all be at different stages of commitment to you and your work. Your communication must respect this and be segmented by audience as much as possible. There are two particular types of reader that deserve special attention and communication.

The new reader. To introduce new people to your work, I recommend the cheese-cube lure. Offer something for free (a free chapter, a blog with cool content, a special digital download, etc). Cast a wide net with something broadly appealing. Then gradually move people into more serious commitments (by earning their trust), such as signing up for your e-newsletter or buying your book.

The true fan. For the readers who would buy anything you ever published, consider special communication and experiences only available to them. You know how your city symphony will have a VIP room with cookies and chocolate during intermission, for certain season subscribers? Think about what your VIP experience looks like, too. For some authors, that means earliest access and cheapest prices for their most loyal fans.

Final note