Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 163

May 19, 2014

Take the 2014 Freelance Income Survey

Do you make a portion of your income through freelance writing?

Then I’d like you to take this survey.

Background

My Scratch co-founder runs a blog called Who Pays Writers? that encourages transparency about pay rates in the media and publishing industries. In the past week, there’s been a lot of chatter about salary inequity in journalism, but that chatter largely ignores a huge part of the media’s workforce: freelancers.

This short survey collects data on the current economic situation for freelance writers. It’s anonymous, and all the results will be shared publicly.

Or, visit this blog post to read even more background.

The post Take the 2014 Freelance Income Survey appeared first on Jane Friedman and was written by Jane Friedman.

May 15, 2014

Which Publishers and Authors Are Truly Engaged in Their Communities? [Smart Set]

Welcome to The Smart Set, a weekly series where I discuss some of the most interesting questions being raised by astute minds in writing, publishing, and media.

“To seek: to embrace the questions, be wary of answers.”

—Terry Tempest Williams

Bridging the Gap: Why Publishing’s Future Is at Risk by Baldur Bjarnason

This blog post at Publishing Perspectives is adapted from a talk given by Baldur Bjarnson at a major European publishing conference. It’s the most worthwhile piece on the future of publishing I’ve read in a while. For some, it will read as fairly dark, but I see it mostly as a very good argument for why every author (and publisher) needs to think beyond the confines of the book. Bjarnason says:

Publishers aren’t in the content business. The core function of a publisher is to help people help themselves. Content—giving people information, lessons, documentation, and stories for them to entertain themselves—just happens to be a good way of doing that. Calling it a content business is just another way of focusing on the product instead of the problems they help solve.

The rise of digital content—websites and apps—is the first time we the consumer have an alternative to the book model to help us help ourselves. It’s not just new kinds of content (blogs, wikis, databases) but also self-documenting tools, better software, online classes and workshops, webinars, and online communities where people help each other.

Digital gives your customers alternatives and ebooks aren’t it. Your ebooks aren’t the new thing. They are the old thing photocopied onto a facsimile of the new thing. Ebooks are nothing more than a print artifact delivered digitally. … The web and apps are the new thing.

Bjarnson’s argument echoes Clay Christensen’s thoughts on journalism (and other fields), where writing/publishing needs to focus on “jobs to be done,” such as “Entertain me for 10 minutes while I wait in line.”

I think it’s fair to argue all of this will unfold differently for nonfiction/information vs. fiction/narratives; Bjarnson might agree, but refers to narratives as explicitly being affected, too:

You are even starting to see it in fiction as new writers have been emerging from online fiction communities. They’ve been appearing on Wattpad, Livejournal, Dreamwidth and similar fan-oriented venues. Storytelling is becoming a mainstream activity—as it should be.

Questions raised:

Bjarnson argues that books represent a convenient way for the community to reward people’s contributions to that community: “A book is just a lever that amplifies appreciation.” What approaches can writers (and publishers) take to earn money from a community-driven creative product?

Bjarnson points out that both traditional publishers and self-publishers are trapped in the old mindset of hierarchical production and linear processes, and don’t see themselves as engaged in communities. What publishers or authors are, in fact, engaged and can serve as models?

Bjarnson predicts most publishers will disappear in the next decade or two, except for a few “corporate behemoths” because they will not be able to serve communities. Yet in the US at least, we see the small presses increasing in number and some flourishing. How are we to reconcile these things (assuming we’re compelled by Bjarnson’s argument)?

Digital-First Publishing and The Troubled Fortunes of Digital-First Publishers by Jane Litte

Traditional publishers aren’t the only ones affected by competition from self-publishing. Digital-first publishers such as Ellora’s Cave, which were celebrated not too long ago at events like Digital Book World, now appear to be in trouble, and other digital presses are now inserting very broad language in their contracts to protect what they consider to be their intellectual property, and to prevent authors from leaving. Litte at Dear Author concludes:

Self publishing and even new digital publishers are hammering away at the base of older and established digital publishers as more and more authors are determined to forge their own path. It’s unsurprising that there are both financial troubles and contractual issues arising out of this.

Questions raised:

What value or services will digital-first or digital-only publishers need to provide authors to remain attractive? (I think we all know the rights grabs in contracts is not a long-term solution.)

Wondering Whether Printed Books Will Outlast Printed Money, or Football by Mike Shatzkin

In a post filled with many questions, industry insider Mike Shatzkin is inspired by a recent New York Times article that attempts to predict what technology will be commonplace in a decade, among other things. Shatzkin asks the following:

How persistent an activity is immersive long-form reading?

How persistent is the demand for printed books for long-form reading?

How much of the creation and selling of books spreads beyond the book business?

What questions do you have? Share in the comments.

The post Which Publishers and Authors Are Truly Engaged in Their Communities? [Smart Set] appeared first on Jane Friedman and was written by Jane Friedman.

May 14, 2014

Do You Need to Rethink Your Website’s Key Elements?

Michael Goodin / Flickr

Note from Jane: On Tuesday, May 20, I’m teaching a 2-hour online class on how to create your own author website using WordPress, in partnership with Writer’s Digest. Click here for more information.

For 10 years, I’ve been analyzing website traffic—for my own site, for Writer’s Digest (when I worked for them from 2001–2010), and now for the Virginia Quarterly Review.

Every site has different traffic patterns, but what I’ve learned is that the homepage is rarely the first page that visitors see. They often end up on a story page from a social media link, or they may visit through a “side door” after conducting a Google search and finding something useful in your archives.

Many writers (and businesses) spend a lot of time thinking about the homepage when they should be thinking about the areas that appear on every single page: the header, the sidebars, the footer, pop-ups, etc.

How you treat those areas (plus how you consider what goes on the homepage) means you’ll need to ask yourself two questions.

For someone coming to my site very intentionally—a reader who knows my work and may be a fan—what are they likely looking for? And what do I want them to know?

For the drive-by visits, especially those that come through a “side door,” what do newcomers need to know right away? What do I want to offer them?

Common homepage visit scenarios

If you’re actively writing and publishing, people who end up on your homepage are likely seeking further information about your latest work or who you are. That’s why the latest book cover (or project) should often be on the homepage and marked as such.

Your bio page and contact page should be in the main menu, as this is another common reason for people to end up on your homepage.

Homepage visitors may be seeking an overview of all the work you have to offer, so make it easy for them to find a page that offers the list in reverse chronological order. If you have a series, have the series title in your main menu.

How to help newcomers

Have a tagline or description in your header—something that appears on every page—that clearly describes the kind of work you do. CJ Lyons makes it clear at her site: Thrillers With Heart.

If you’re actively posting new content or blogging at your site, you’ll get most traffic to your posts, not your homepage. Make sure your sidebar offers a means to subscribe, to search your archive, or to browse by category. (Many established bloggers list their most popular posts in the sidebar.) Your site’s main menu or navigation should make the content, themes, and depth of your site very clear.

If you’ve been actively promoting something specific—whether on social media or traditional media—make sure your site refers to that something specific, or helps people find that something. This is also helpful if you get a really significant media mention somewhere; have a welcome message or post for those people. “Did you hear my interview with Terry Gross? Click here.”

Maximize the traffic you get

Most people who visit your site will never return. Offer them other ways to engage with you (or even offer them a free sample of something). This is why social media icons are so prevalent on website headers/sidebars, and why professional authors have e-mail newsletter signups very prominent on every page. It helps better capture visitors at the moment they’ve expressed a glimmer of attention.

Explicitly state, “First-time visitor? Start here.” This is useful for sites with lots of content that can be overwhelming for the newcomer.

Make the tough decisions: if people only spend 10-15 seconds on your site, what should they not leave without knowing? Your header and/or your sidebar area need to convey this quickly.

If people reach the bottom of a page or post, they are very engaged. This is a prime opportunity to add a call to action, such as an email newsletter sign-up, or mention a book for sale.

Remember: for active authors, who are frequently publishing, your strategy or focus may change every 6–12 months, which means your site has to change, too. A website is never something you launch and leave. It has to be updated to be effective.

For more on author websites:

10 Ways to Build Long-Lasting Traffic to Your Website or Blog

3 Ways to Improve Your Author Website

3 Ways to Improve Your Website Design

5 Keys to Writing for an Online Audience

Building Your First Website: Resource List

Is Your Author Website Doing Its Job? 6 Things to Check

The Big Mistake of Author Websites & Blogs

WordPress Plug-ins I Can’t Live Without

Note from Jane: On Tuesday, May 20, I’m teaching a 2-hour online class on how to create your own author website using WordPress. Click here for more information.

The post Do You Need to Rethink Your Website’s Key Elements? appeared first on Jane Friedman and was written by Jane Friedman.

May 13, 2014

Being an Author vs. Running a Business as an Author

Is there a difference between being an author versus running a business as an author? In this interview with Joanna Penn, we discuss some of the important shifts that happen when you begin treating your writing (and/or your art) also as your business.

We also cover:

The trade-offs that can make full-time writing possible

The business models that writers are using these days

The commonalities of authors making over $100,000 per year

Understanding the profit and loss statement for your book

Joanna offers up our interview in three ways:

A 45-minute video you can watch

A transcript at her blog

An audio-only version (at the top of the page)

I’m grateful to Joanna for inviting me as a guest on her series, and hope you find some useful takeaways in our discussion.

The post Being an Author vs. Running a Business as an Author appeared first on Jane Friedman and was written by Jane Friedman.

May 8, 2014

Why Are Harlequin Profits Declining? [Smart Set]

Welcome to The Smart Set, a weekly series where I discuss some of the most interesting questions being raised by astute minds in writing, publishing, and media.

“To seek: to embrace the questions, be wary of answers.”

—Terry Tempest Williams

HarperCollins Acquisition of Harlequin and What It Means for Readers by Jane Litte

This piece at Dear Author focuses on the recent acquisition of Harlequin, but offers us a moment to consider that Harlequin’s profits have been declining since 2010. (However, that is not necessarily why it was sold by the parent company, as Litte points out.)

Why should Harlequin, as one of the most recognizable publishing brands in the market, with a clear target demographic, not be flourishing—especially as genre fiction is selling better than every other category in the ebook/digital age? Doesn’t Harlequin symbolize what everyone says is essential for a successful publisher of the future, with their direct-to-consumer reach and strong reader-friendly policies? Litte offers an excellent, informed overview of why it’s declining (in brief: mass-market print sales are WAY down, plus there’s increased competition), then discusses her fears that HarperCollins will mess things up for the future of Harlequin.

Questions raised:

Will Harlequin’s reader-friendly policies rub off on HarperCollins, or will they become more like the rest of the publishing community (that is: not-so reader friendly)?

Despite Harlequin’s reader-friendly policies, their digital growth hasn’t made up for the decline in print. Competition from self-publishing is undoubtedly having an impact. How much does Harlequin represent a canary in the coal mine for the rest of publishing? (Additionally, Harlequin faces a lawsuit from authors who claim they were shortchanged on royalty earnings—that can’t help matters when authors are considering how or with whom to publish.)

OMG! What If Barnes & Noble Closes? by Rachelle Gardner

There is a “rumor” that Barnes & Noble may close by the end of year—which is not a rumor I’m inclined to spread, because I think it has no basis and is nothing more than remorseless click bait by its originating author (not Gardner)—but it does pose an interesting thought experiment. What happens if the largest chain bricks-and-mortar bookstore retailer closes? Gardner discusses why it would not be an epic tragedy if B&N ceased to exist.

Questions raised:

How critical is the physical bookstore browsing experience to traditional publishing sales? What can it be replaced by? (What is it already replaced by?)

How much does the independent bookstore and/or library system stand to gain/benefit from such a loss?

What might be some surprising consequences or opportunities presented by the closure?

The Novel Is Dead (This Time It’s For Real) by Will Self

For a couple years now, I have been quoting a Guardian interview with Will Self, where he says, “I don’t write for readers.” (I use it when I teach about the philosophy and strategy of author platform, and try to clear the room first of people who take Self’s position, since platform growth is often driven by reader and community engagement and outreach.)

In any case, this long, florid piece by Self will be no surprise to those of us already familiar with his views. I find myself in the unusual position of both agreeing and disagreeing with him: the literary novel is a specialized interest (we agree), but I also think that’s always been the case (we disagree).

Questions raised:

Is the novel really truly dead? (I write this tongue in cheek.) I love this Twitter account that was created in response.

Seriously, though: I have noticed lately (in the last year or so), more and more people talking about reading, particularly the reading of literary fiction, as a moral activity, a way of fostering empathy. To me, this is a worrying sign—that people who love the artform of the literary novel are motivated to grant it some kind of moral high ground to “save” it, or that it must be considered to have special abilities that no other medium can match. I’d rather think more broadly and innovatively about how writing or stories can find an audience in a digital era. Is the literary novel itself not a construct of our particular time and place in history, developed to be a certain length and delivered in a certain package? What happens when writing isn’t best delivered between two covers, or even in ebook form? These static forms aren’t well-suited to survive (in the long, long term), and I don’t find it helpful to hold them up as sacred. Maybe the question here is: What are we afraid of happening? Or what is the worst thing that might happen if the (literary) novel is declining?

What questions do you have? Share in the comments.

The post Why Are Harlequin Profits Declining? [Smart Set] appeared first on Jane Friedman and was written by Jane Friedman.

May 7, 2014

The Role of Faith (the Non-Religious Kind) in the Writing Life

The latest issue of my magazine Scratch is now available! The theme is Faith. If you’re not a subscriber, here’s what you can read for free.

The Scratch Interview by Cheryl Strayed by Manjula Martin

In this revealing interview, New York Times bestseller Cheryl Strayed talks about success, artistic faith, and how to bounce a rent check while you’re on the bestseller list. A snippet:

I feel strongly that we’re only hurting ourselves as writers by being so secretive about money. There’s no other job in the world where you get your master’s degree in that field and you’re like, well, you might make zero or you might make $5 million! We don’t have any standards in that way, and we probably never will. There will always be such a wide range of what writers are paid, but at least we could give each other information.

Click here to read the full interview (you won’t be sorry, but you will be asked to register as a free user).

Photo Essay: Library Road Trip by Robert Dawson

A father and son set out to photograph public libraries across America and discover beauty, decay, and endurance in the public commons.

Thumbsuckers: Intellectual Work in the Culture of Austerity by Ellen Willis

On the corporate takeover of artistic work in the 1980s—and how it changed this acclaimed critic’s career.

The Panda Ambulance by Beth Lisick

Odd jobs, power moms, and a small revenge.

If you subscribe, then you’ll also get access to the following stories:

Contracts 101: Subsidiary Rights. This is part of my continuing series on book contracts and what you need to know before signing on the dotted line.

Deconstructing the Book P&L. My in-depth breakdown of how most publishers decide what books to publish, including a downloadable spreadsheet.

From High Times to Publishing Futurist. My interview with magazine industry insider Bo Sacks.

The Scratch Roundtable: Creative Writing Professors . Esteemed authors and professors talk about writing students, creative writing degrees, and what place business has in the classroom.

Freelancer’s Journal: The Content Farmer. Andi Cumbo-Floyd reveals what a typical day is like in the life of a copywriter and social media ghostwriter.

And more! Review the entire table of contents.

Not already a subscriber? Become more savvy about the business side of the writing life for only $20/year.

The post The Role of Faith (the Non-Religious Kind) in the Writing Life appeared first on Jane Friedman and was written by Jane Friedman.

May 5, 2014

Reasons to Be Optimistic During the Disruption of Publishing: A Few Thoughts Following My Muse Keynote Talk

Yesterday, I gave my keynote on Writing for Love (and Money) at The Muse and The Marketplace annual conference, hosted by Grub Street in Boston. While I think I delivered the exact presentation I intended (success!) and sparked some healthy debate afterward, a few questions from the audience indicated that I hadn’t necessarily changed hearts and minds—and that many aspects about the evolving business model for writing and writers remain unclear or confusing.

This follow-up post is meant to (1) address those questions in a more thorough and intelligent way than I was able to muster on the spot, and (2) offer some practical information that I didn’t have time to cover in my talk.

How can we accept the decline of newspapers and magazines, and the quality journalism therein, or accept the exploitation of writers? How can we retain valuable reporting, which requires payment?

One of the limitations of my talk was that it focused primarily on the history of book authorship and creative writing, more so than the fortunes of newspaper and magazine publishing or freelance journalists. I consider writing for hire (freelancing and journalism) quite different than creative writing (novels, memoir, etc), because the former necessarily has to pay attention to marketplace concerns, and if not, be gifted into existence or sustainability by patrons, grants, fellowships, and so on.

Journalists don’t typically expect—or shouldn’t expect—to make a living from their work by just writing what they want and disregarding the market. A creative writer, on the other hand, is usually assumed to be focusing on his art and mostly disregarding trends, though what he writes is of course influenced by what can be sold. For instance, short stories once could bring a writer decent pay, as it did F. Scott Fitzgerald, but one is quite lucky to earn any money from short fiction today. And serials could be very profitable for Dickens during the Victorian Era, but the form later fell out of favor for long fiction. (And serials may now be making a comeback because of their suitability for mobile distribution and consumption.)

Nevertheless: Too often we equate content with its container. For much of our lives, quality journalism has appeared in newspapers and magazines, so we equate the decline of that particular industry with the decline of journalism. But the survival of quality writing or journalism is not tied to the future of the newspaper or magazine business. Those are delivery and distribution mechanisms, they are services to readers, and they have become less useful and valuable to us in the digital era.

The challenge, of course, is that we know how to monetize a print newspaper or magazine—and it’s easier to charge for their perceived value. We’re still figuring out how to monetize digital forms. But amidst this challenge, I’d argue we’re not seeing less quality journalism today, we’re seeing more, because we have no distribution barriers and low start-up costs in digital publishing. I’d also ask if we really think the system pre-Internet was producing quality journalism, or if we merely prefer the devil we know. In the mid-20th century, media began to be operated by handful of conglomerates with significant control over the mass mediums of radio, TV, newspapers and magazines, a system that was hard for outside voices to access. To be sure, these major media conglomerates are being disrupted by another set of powerhouses (Google, Apple, Amazon, Facebook), but the latter provide us possibilities that didn’t exist before: the ability to directly reach a specific, targeted readership and gather a community, which can lead to monetization by individuals and businesses alike.

How long does it take to reach sustainability? It depends on what kind of community you’ve established and if you offer a compelling value they find deserving of their dollars. Let’s look at a few examples of people or institutions experimenting and succeeding in the digital era.

Brain Pickings

In 2006, Maria Popova started her site Brain Pickings, which is a catalogue of “interestingness.” Today, her work reaches millions through her website and email newsletter, and it’s sustainable through donations and affiliate marketing (more on that below). I recommend watching her talk at Tools of Change, where she discusses how journalism can sustain itself in the future. Popova is clearly doing what she loves, and has found a business model to serve her art.

The Information

Launched last fall, The Information is a subscription-based digital publication that costs $399 per year. It’s focused on a niche market, the technology business audience. What is the value or benefit to readers? High-quality stories and journalism that can be trusted (unlike much online content in the tech industry), and an implicit promise that you, the reader, are getting the smartest viewpoints and insights—in a very efficient way, I might add. You don’t have to filter through the noise of the many tech journalism sites to figure out what’s important.

Stratechery, Ben Thompson

Thompson just recently began a monetization effort for his insightful tech industry blog that offers incentives for people to become members. Those incentives include: the ability to comment on articles, direct email access to Thompson, daily updates, virtual and in-person meet ups, and a private online community.

The Wirecutter

This website offers high-quality product reviews, mainly in the tech/media product space, and sustains itself through affiliate marketing.

Chris Guillebeau

An author and world traveler, Chris’s brand centers on the art of nonconformity, and I often recommend writers read his 279 Days to Overnight Success, which details how he made his website and blog a sustainable living in just under a year. He makes money from selling his own digital products and traditionally published books, as well as producing events.

And of course you also have the big guns, Andrew Sullivan and Nate Silver, but they are so often pulled out as models that I won’t belabor their trajectories here. I should also point out there are many valuable digital-era operations that give us plenty to be optimistic about when it comes to the future of journalism, such as ProPublica, a nonprofit, and the Pacific Standard, another nonprofit run out of the Miller-McCune Center for Research, Media and Public Policy. (In my mind, nonprofits and for-profits face the same issues of sustainability and have the same challenge of balancing art and business.)

Regarding payment for writers: When The Atlantic Online got in trouble last year for offering Nate Thayer $0 to re-post an article, Alexis Madrigal wrote a very long response about how and why freelancers were offered so little payment for their pieces. (We also discussed this at the web editor roundtable for Scratch.) Madrigal explains Atlantic’s strategy of using in-house writers and editors to generate the large majority of content that goes online, because it’s a more successful way of getting quality content and higher traffic. The freelance work often contributes very little to the bigger picture, thus the lower investment.

This is a frustrating reality for freelancers, and obviously it’s become more difficult to make a living as a freelance journalist. Some argue it’s next to impossible to make a living as an online-only freelancer, unless you supplement it with other forms of writing. Felix Salmon sums up the challenge best:

The lesson here isn’t that digital journalism doesn’t pay. It does pay and often it pays better than print journalism. Rather the lesson is that if you want to earn money in digital journalism, you’re probably going to have to get a full-time job somewhere. Lots of people write content online; most of them aren’t even journalists, and as Ariana Huffington says, “Self-expression is the new entertainment.” Digital journalism isn’t really about writing any more — not in the manner that freelance print journalists understand it, anyway. Instead, it’s more about reading, and aggregating, and working in teams, doing all the work that used to happen in old print-magazine offices, but doing it on a vastly compressed timescale.

When I recently interviewed longtime magazine industry insider Bo Sacks for Scratch, he discussed how it’s survival of the fittest for many publications that have traditionally been supported through advertising. He said:

If you do not have excellence, you will not survive in print. There’s plenty of indifferent writing on the web—it’s free entry, and it doesn’t matter. But quality will out there, too. Really well-written, well-thought-out editorial will be the revenue stream. You must have such worthiness that people give you money when they don’t have to, since they can get entertained elsewhere for free.

People giving you money when they don’t have to? What might inspire that? The answer lies in focusing on the why underlying what you do, the fundamental motivation driving your writing, publication, or business. There’s enough choice and community out there that most people only have time and money to devote to things they can feel a part of, or believe in, or simply can’t get anywhere else. For more on this, watch Simon Sinek’s video below.

There’s an abundance of jabber and dreck, and we’re more distracted than ever. How is all this low-quality work affecting us?

This question comes up at almost every talk I give these days, and I think each person is asking a different question. It can mean so many different things:

I am appalled at the quality of work published today.

I am worried low-quality work will push out the high-quality work.

What will happen to us as a culture/society if we allow low-quality work to proliferate?

I am overwhelmed and anxious by all the horrible stuff out there. Will I lose what I love?

I am tired of people talking about what they had for breakfast.

These are concerns that have been expressed literally since the beginning of publishing. (Here’s an excellent summary.) After the printing press was invented, and the world started filling with books, intellectuals worried that the abundance would negatively affect people’s consumption of the most worthy content. When novels emerged, they were accused of being light entertainment that would rot the mind. One intellectual, dismayed at the quality of literature being produced in the 1700s, commented:

Reading is supposed to be an educational tool of independence, and most people use it like sleeping pills; it is supposed to make us free and mature, and how many does it serve merely as a way of passing time and as a way of remaining in a condition of eternal immaturity!

Even as literacy spread, and more people learned to read, some were concerned that such a solitary activity would detract from communal life. And it did, but there were other benefits. Elizabeth Eisenstein writes in The Printing Press as an Agent of Change:

By its very nature, a reading public was not only more dispersed; it was also more atomistic and individualistic than a hearing one. … To be sure, bookshops, coffee houses, and reading rooms provided new kinds of communal gathering places. … But even while communal solidarity was diminished, vicarious participation in more distant events was also enhanced; and even while local ties were loosened, links to larger collective units were being forged. Printed materials encouraged silent adherence to causes whose advocates could not be found in any one parish and who addressed an invisible public from afar. New forms of group identity began to compete with an older, more localized nexus of loyalties.

An identical passage could be written about the dynamics of the digital age!

When you recognize this overriding pattern, the same concerns arising again and again throughout history, we should take consolation in it. Perhaps, just perhaps, we will manage much as we have in the past. New problems arise, but we find enough solutions to carry on. I don’t believe the new problems are any more dire or pernicious than those our predecessors faced. For more reading on this, I highly recommend Google Isn’t Making Us Stupid … Or Smart by Chad Wellmon.

Finally, when it comes to low-quality operations disrupting high-quality operations (think: Huffington Post disrupting print newspapers), people forget that these low-quality operations often evolve and mature into high-quality operations. This is one of the ideas expressed in Clay Christensen’s The Innovator’s Dilemma. One of the classic examples he uses is how the Detroit automakers scoffed at the low-quality compact cars coming out of Japan in the 1960s. We all know how that story ended, and Japan now makes all quality of cars, not just those for the low end of the market. We’ve already seen how outlets like Buzzfeed are implementing journalistic standards and getting closer to what traditionalists consider quality journalism.

Bottom line: I think arguments about quality aren’t productive or taking us anywhere new. There is an audience for all types of quality; know your market and serve the quality that’s appropriate—and remember that the price reflects the quality. (If you were paying for this blog post, I would be approaching it very differently, and would spend more than a few hours on it.)

What are the new business models for writers? How can they make money in the digital era?

This is a big question, and it’s why I started Scratch in partnership with Manjula Martin. We explore this question, in all its facets, in each quarterly issue and on the blog. It’s not a question that can be answered with a formula, nor decisively, because the environment is still dramatically changing, and every author is different in terms of their strengths, available time to invest, and what they are willing to sacrifice to earn a living from writing. One of the major points of my talk was that successful authors often buck the trends or economic models of their time, and find new ways of sustaining their art. They ignore prevailing cultural attitudes that often inhibit innovative thinking.

However, I can point to trends in the market and the different models that are currently playing out.

Serials

I reported at length, again for Scratch, on how fiction writers are using platforms like Wattpad, Amazon KDP, and Kindle Serials to build an audience and then monetize it. (You can read the free version of the article here.)

Two keys to this model:

People get to sample your work for free, which builds trust, and then later on you charge, once you have a devoted reader. This model is prevalent in the digital age and tech world: capturing new users (or readers) with a free or freemium service, then charging the most devoted users (or readers) for the full experience.

Serials do well in a mobile reading environment, and given that we’re nearly at 100% mobile adoption in the United States, more and more reading needs to be optimized for that environment. Wattpad has been very successful at this; the majority of reading activity on their platform is mobile-driven.

Crowdfunding

Everyone has heard of Kickstarters by now. Writers have been funding their projects for years through this platform. But to be successful, it requires that you’re able to mobilize a community or fan base, who comes to your aid in support of your project. How do you develop that community or fan base in the first place? It could be through serials (described above), blogging, working your ass off getting published and noticed in a variety of outlets online, being on social media, and so on. Successful crowdfunding usually comes after years of putting in the work to develop a readership, rather than at the beginning of a writing and publishing effort.

Advertising and affiliate marketing

If your website or blog has sufficient traffic, you can monetize through advertising (there’s an ad network specifically for the literary community) and affiliate marketing, where you get a small percentage of sales when people buy something because they were referred by your site. Amazon has the largest and most successful affiliate program, and I am an Amazon affiliate myself, to help cover the costs of maintaining this site.

Donations and tip jars

Maria Popova (mentioned above) sustains herself through a combination of donations and affiliate marketing. Many bloggers who otherwise write for free have a tip jar on their site to encourage readers to pay for content that they’ve found valuable. You won’t find a tip jar on my site, but that’s mainly because I’ve monetized successfully in other ways, and also I’ve been too lazy to incorporate one. However, my magazine Scratch works on a subscription and donation model, of which donations have been a very important part of our overall financial picture. Which brings me to …

Subscriptions and memberships

Since its launch in October 2013, my digital magazine is now approaching 600 paid subscribers. People do pay for content if they find value in it or can’t get it elsewhere. I also think people subscribe because they believe in our mission and want to be a part of what we’re doing. Subscription and membership models work well when you have a very well-defined target audience, with common values and beliefs, where people are motivated to be part of the community, and/or want to directly support your efforts. See also: Andrew Sullivan.

Collectives

There have been experiments, formal and informal, with author collectives, where authors who share similar audiences band together and cross-market and promote themselves to each other’s audiences. One of the more recent examples of this is The Deadly Dozen, twelve thriller writers who bundled together their work digitally and sold it at a very competitive price. The project hit the New York Times bestseller list, and you can bet that every author now has increased visibility and a new set of readers they didn’t have before.

Experiences, services, and events

While at The Muse & The Marketplace, I met author Jamie Cat Callan, who is the author of Ooh La La! French Women’s Secrets to Feeling Beautiful Every Day. This summer, Jamie is taking 14 ladies on a tour of Paris, to learn the secrets discussed in her book.

While such a strategy plays well for nonfiction authors, sometimes it’s tougher for fiction writers to make a connection to an “experience” that would be inspired by their work. But places and themes in books can often parlay into discussions, events, and experiences that devoted readers would pay for (or that help sell books), especially if you can partner with one or two others who are writing about the same places and themes.

For an example of a literary author doing gangbusters on the events/experience side, see Daniel Nester’s The Incredible Sestina Anthology.

Good old-fashioned sales

I don’t believe the value of content is approaching zero or that it’s meant to be free or gifted. Certainly some content has a market value of zero and it’s often very smart to make some content available for free as part of a larger content strategy. This blog, for instance, is 100% free, yet it is one of the most important ways I make money. The value of the content here attracts 100,000 visits every month, and ranks at the top of Google searches for how to write and get published. Significant opportunities come from that—opportunities I haven’t even fully capitalized on yet because I have a day job.

Every decision you make as a writer has to be made with the bigger picture in mind—of how a particular book, article, blog post, or social media effort attracts a certain type of reader, and how you expect to “funnel” that reader to the next experience if they enjoy your work. Genre fiction authors have been expert at this, and have built up incredible communities of fans who end up spreading the word on their behalf. Taking care of your readers means also taking care of your sales, and the digital era has brought us an abundance of models and means to engage and interact with readers, and turn that into a sustainable living.

Michael Bhaskar, in The Content Machine, writes:

More models allow more points of views, more ways of thinking and more ways of existing. This freedom creates a better chance of innovative and different work coming through … Diversity of models is hence always to be encouraged.

This has not been an exhaustive list of all the ways that writers can make money, either from direct sales or through other means, but I hope it helps get your wheels turning. As I see it, the challenge isn’t really about a lack of opportunities or models, but the average person’s lack of time to pursue these things, or the lack of stamina (these strategies take time to pay off—it’s rarely a quick win), or the desire for a sure success and a low tolerance for failure. Some experiments or models will fail, and that’s where people often stop and decide “game over.” If I had stopped my blog after its first uneventful 18 months, or abandoned Twitter after 18 months, I would say they were both a waste of time. But I stuck with them, and they paid off.

The greater challenge

As I discussed in my talk, we’re approaching an era of universal authorship. Anyone can and does write now, and because of that, the writers who know how to find and engage their readership or community (to tap into the why), and who enter into collaborations with other authors and artists, hold a dramatic advantage. Future-of-the-book expert Bob Stein has said that if the printing press empowered the individual, the digital era now empowers collaboration.

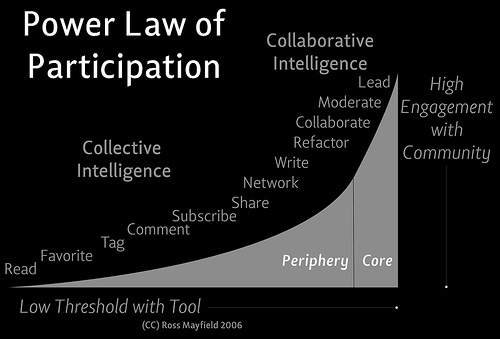

You can find an expression of this in The Power Law of Participation, where you see the qualities of moderating, collaborating, and leading as requiring and producing high levels of engagement with a community—a coveted thing when attention is scarce.

Every writer knows you have to spend time on your writing for it to get better, and to produce something that’s special. The same is true of every activity described above, including any social media efforts you pursue. We’re seeking long-term sustainability, and it’s an organic process that’s nearly impossible to rush.

Parting words

Sometimes we can get so caught up in what we’ve lost that we don’t see what we’ve gained. We fail to see the opportunities right in front of us because we’re focused on the qualities of a system that we find exploitative or antithetical to our values. My hope is that my Muse & Marketplace talk opens up people to the art of possibility, to recognize the abundance we have. To do this, it helps to focus on the higher motivations of what we do (our gifts) and pursue excellence through our work and play, rather than focus on the outcomes. I’m not sure how successful I was, and I find myself already thinking of new stories to tell to help convey this idea—because the anxiety and fear is not helpful and needs to be quashed.

I’ll end this post with a brief video that I showed at the end of my talk, with wise words from authors who carry an attitude that fuels (or fueled) their success. My favorite quote is from Joseph Campbell, who said:

Is the system going to flatten you out and deny you your humanity, or are you going to be able to make use of the system to the attainment of human purposes?

For more:

My reading list for my Digital Media & Publishing class at UVA

A Frank Conversation With the Former Editors of the Washington Post and New York Times [on the future of journalism]

The Future of the News Business by Marc Andreessen

Show Your Work by Austin Kleon

Make Art Make Money by Elizabeth Hyde Stevens

Audience Development for Writers: my 20-minute talk about how I built my own audience over time

The post Reasons to Be Optimistic During the Disruption of Publishing: A Few Thoughts Following My Muse Keynote Talk appeared first on Jane Friedman and was written by Jane Friedman.

May 2, 2014

Let’s Resist the Culture of Idolatry in American Literature

photo by Donald E. Byrne, III

In a bold and insightful piece by writer Monica Byrne, she discusses how, as an emerging writer, she created a list of her favorite authors titled “My Idols.” But she scratched that out, then wrote “My Models.” Then, finally, “My Peers.” Why?

… I realized the difference between admiration and idolatry. How I placed the famous writer’s innate talent beyond my grasp. … There was nothing essentially different about me and my capabilities, except time and practice. However, I notice a strong culture of idolatry in American literature that restricts writers’ sense of possibility for themselves—as if their idols produce nothing but genius unapproachable work; and also, as if it’s not even conceivable they could ever be as good. But it’s just not true.

Read the entire piece—inspiring and honest. And when you’re done, check out these other essays on writing over at the latest Glimmer Train bulletin:

The Blank Page by Melanie Lefkowitz

Having Children Might Actually Help Your Writing by Brian Gresko

The post Let’s Resist the Culture of Idolatry in American Literature appeared first on Jane Friedman and was written by Jane Friedman.

May 1, 2014

The Role of the Expert Has Radically Changed [Smart Set]

Welcome to The Smart Set, a weekly series where I discuss some of the most interesting questions being raised by astute minds in writing, publishing, and media.

“To seek: to embrace the questions, be wary of answers.”

—Terry Tempest Williams

TripAdvisor Hires Wendy Perrin As Its Travel Evangelist by Jason Clampet

After more than 20 years with Condé Nast Traveler magazine, Wendy Perrin is leaving for TripAdvisor, the world’s largest travel site, which is driven primarily by user-generated reviews. At TripAdvisor, Perrin will generate new content and act as a curator of user content. (For those not in the know, Perrin is well-known and respected in the travel community.)

Perrin says:

The role of an expert has changed radically in the past two decades. Expertise used to be a one-way broadcast. Now it’s a group conversation. I think today the job of a travel expert is to engage travelers, harness their wisdom, and distill it. The TripAdvisor community is contributing millions of up-to-the-minute individual experiences. I hope to help filter those through the breadth of my global experience and produce a set of information that is empowering to all.

Questions raised:

Something that also happened last week: Ladies Home Journal shuttered. How do traditional magazine brands remain relevant and compete effectively in the digital space?

What magazine brands are positioned well for the digital age? (This is a question I asked expert Bo Sacks for an interview at Scratch.) From my perspective, the ones who are doing it well offer far more than a periodical. They’ve developed a community around a single purpose, vision or mission—and that community is served in many ways, not only through a magazine.

I think TripAdvisor will be around for much longer than Condé Naste Traveler. What do you think?

What Every Literary Writer Needs to Know About the Digital Disruption: a series of posts and interviews by Porter Anderson

Tomorrow, at the Publishing Perspectives website at 1:30 p.m. ET, you can watch a live stream of a panel discussing literary work in the digital age. We will discuss why we don’t hear more about literary authors charging ahead with digital self-publishing, what literary authors can learn from genre writers in this area, and whether literary fiction can cultivate its audience in social media as readily as other genres.

Yes, I’m one of the panelists. In the lead up to this panel, journalist Porter Anderson has been featuring previews and questions from people like myself. So far:

Read my thoughts

Looking for Literary in Digital Places, featuring Eve Bridburg of Grub Street

Benjamin Samuel on Literature’s Future

Eve comments:

I don’t see online communities growing up around literary authors and books in quite the same way I see it happening for genre fiction and fan fiction.

Questions raised:

What or where is the larger discovery platform for literary authors—particularly as physical bookstore discovery is replaced by online discovery?

Where are the online communities for literary authors and readers?

How do you want to define literary—perhaps the biggest can of worms of all?

Should we be angsty/worried about these questions in the first place? Will these issues resolve themselves in their own good time?

The Disruption of the Disruption Is Temporary by Mike Shatzkin

There’s a wide belief or understanding that digital growth for the big publishers has plateaued and we’re all getting back to “business as usual.” But are we? Shatzkin writes:

… even if the contractual 25 percent royalty is slow to change, the big authors will almost certainly be demanding (and getting) advances based on the total margin expectation, not the 25 percent. And the price of ebooks is going to continue to be driven down, also not a good thing for the publishing establishment.

Shatzkin lists 6 other reasons for publishers not to get too comfy.

Questions raised:

Where are we at in the “disruption” of traditional publishing? What other pain points are yet to come?

How much further will ebook prices be driven down?

How much profit will publishers have to cede to authors, and to retailers?

What questions do you have? Share in the comments.

The post The Role of the Expert Has Radically Changed [Smart Set] appeared first on Jane Friedman and was written by Jane Friedman.

April 24, 2014

Will Self-Pub Dwindle When There’s Less Backlist for Authors to Exploit?

Welcome to The Smart Set, a weekly series where I discuss some of the most interesting questions being raised by astute minds in writing, publishing, and media.

“To seek: to embrace the questions, be wary of answers.”

—Terry Tempest Williams

When an Author Should Self-Publish and How That Might Change by Mike Shatzkin

Industry insider and analyst Mike Shatzkin lays out the value of a traditional publisher, and then goes on to explain when it makes more sense for an author to self-publish. Those scenarios include:

Releasing more than one book per year

Releasing material that isn’t traditional “book” length

Releasing backlist titles — and this one especially

However, Shatzkin finds reason to believe that the desirability of self-publishing may wane over time as publishers adapt to the new market and:

Have digital-first imprints with more flexible contracts or attractive deals

Publish a wider range of work, of varying lengths

Raise royalties

Shatzkin concludes:

Self-publishing and new-style digital-first publishing can grow more to the extent that the book-in-store share of the market shrinks more. But while that’s happening, the big publishers are also adding to their capabilities: building their databases and understanding of individual consumers (something that all the big houses are doing and which the upstarts seem not to believe is happening, or at least not happening effectively), distributing and marketing with increasing effectiveness in offshore markets, and controlling more and more of the global delivery in all languages of the books in which they invest.

Questions raised:

Will self-publishing diminish in attractiveness when there’s less backlist for authors to capitalize on?

If publishers raise royalties, how much less attractive does self-publishing become?

How big of a role does autonomy play in authors’ decisions (as opposed to earnings)?

How much will traditional publishers be able to match the dynamic pricing and release models that successful self-pub authors have pioneered?

Is Reading Anti-Social? by Laura Miller

Miller’s piece is sparked by the recent sale of Readmill, a social reading platform, to Dropbox. (The service will not be continued.) Some in the publishing industry have taken it as a larger sign about the viability of social reading—that reading doesn’t want to be social.

The Readmill sale doesn’t particularly interest me, but the idea of social reading does. Social reading—at least as it’s perceived today—means seeing and sharing comments on a text, or building a conversation around a text, usually within a particular community. Thought leader Bob Stein has laid out a taxonomy of social reading here.

We all tend to take it for granted that reading is a solitary (even sacred) activity, but that behavior is fairly new in our history, as Stein would tell you. He argues that as texts move from print to digital, the social aspect of reading (and writing, for that matter) moves to the foreground. Read more about his ideas here.

Questions raised:

Was Readmill before its time, or will social reading never take off?

Might social reading take off if implemented by Amazon?

Toward a Fair Non-Compete Clause by James Scott Bell

Author James Scott Bell discusses a disturbing clause he recently saw in a New York publisher contract: a very far-reaching non-compete clause that would not allow the author to write, publish, or produce similar material outside of that particular publisher.

Why are these clauses becoming so restrictive and unreasonable? To crack down on self-publishing efforts, primarily.

Questions raised:

How prevalent are these clauses? Are agents seeing them too?

Are such restrictive clauses going to become the new normal?

We’ve now come full circle to questions raised by the Shatzkin piece: if publishers are to become more “current” with their deals and contract templates, these kinds of clauses couldn’t possibly be acceptable to authors—right?

What questions do you have? Share in the comments.

The post Will Self-Pub Dwindle When There’s Less Backlist for Authors to Exploit? appeared first on Jane Friedman and was written by Jane Friedman.

Jane Friedman

- Jane Friedman's profile

- 1882 followers