Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 164

April 23, 2014

Are There Limits to Literary Citizenship?

by Sal Falko / Flickr

The backlash against Literary Citizenship is underway, and perhaps it was inevitable.

For those unaware of term, it’s widely used in the literary, bookish community to refer to activities that support and further reading, writing, and publishing, and the growth of your professional network. In some ways, it’s a more palatable (or friendly) way to think of platform building.

What I’ve always liked about the Literary Citizenship movement:

It’s simple for people to understand and practice. It aligns well with the values of the literary community.

It operates with an abundance mindset. It’s not about competition, but collaboration. If I’m doing well, that’s going to help you, too, in the long term. We’re not playing a zero-sum game where we hoard resources and attention. There’s plenty to go around.

In her piece All Work and No Pay Makes Jack a Dull Writer: On Literary Citizenship and Its Limits, Becky Tuch raises a red flag on all this positive spin, and points to a downturn in publishers’ marketing budgets:

Who, then, must make up for this [economic] shortfall? Certainly it’s not the owners and CEO’s of publishing companies who lend a hand to writers in times of duress (in spite of the fact that their profits are derived precisely from those writers). No, it’s writers who are expected to look after themselves and one another.

Tuch argues that writers are being exploited under the guise of marketing activities as “enriching” activities. She asks us to question and challenge this system, and the corporate publishers or corporate-culture machinations that have led us to the necessity of literary citizenship, and calls for “frank discussions about labor power and financial remuneration.” She is also kind and generous enough to mention Scratch magazine as a step in the right direction, a publication I started in partnership with Manjula Martin, to have more transparent conversations about the economics of writing and publishing.

Manjula and I live on different coasts, and this is something that, if we lived closer to each other, I’d run off to a coffee shop and talk to her about for an afternoon—because I think we have different approaches to this issue (which helps strengthen the publication, I’d argue).

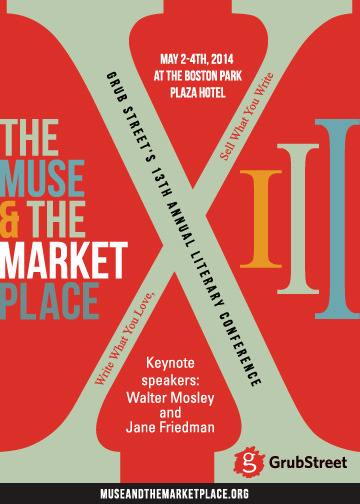

Here’s a high-level summary of my own approach to this—and it’s something I’ve been deeply contemplating the last few months as I’ve prepared for my keynote talk at The Muse and The Marketplace on May 3 (a talk that is free to the public, I might add).

1. The disruption faced by publishing affects the entire media industry (and the world) and goes beyond economics. Publishing is not a specialized activity any longer. Anybody can publish. That’s not to say anybody can publish well, but publication alone is not meaningful in and of itself in many cases. From the time of Gutenberg until roughly 2000, to print and publish something was to amplify it because of the investment and specialized knowledge required. That’s largely not the case today (though for some print-driven work, it still is). To amplify something takes a different kind of muscle, and amplifying through print distribution is becoming less and less meaningful as 50% of book sales now happen online (whether for print or digital books). Publishers of all types and sizes are struggling with this disruption and what it means for their value to authors, readers, and the larger culture.

2. Authors can transcend publishers when it comes to reader loyalty. Most of us don’t buy books because of who published them; we buy them because of who the author is. And if we don’t know the author, we often buy based on word of mouth. Publishers try to encourage this word of mouth, but few have brand recognition or connections with actual readers, because they haven’t traditionally been direct-to-consumer companies. They’ve sold to middlemen instead—bookstores, libraries, wholesalers.

In the last 5-10 years, authors have gained tools to connect directly with readers—tools that they’ve never had before—which give them tremendous power amidst the disruption. This is power that many publishers still lack.

Unfortunately, in the literary market, involvement with the readership is often seen as undesirable—writing for an audience or engaging with them is seen to lessen the art. (“I don’t write for readers” — you’ve heard that one, right?) I won’t address the problematic nature of this belief here, but this cultural myth is prevalent (I’m using the word “myth” neutrally here—as in Joseph Campbell “myth”), and may be the subtext of some criticism of literary citizenship.

3. The abundance mindset trumps the victim or scarcity mindset. In Zen terms (pardon my Zen nature): are we going to see ourselves as part of the publishing world, or as acted upon by the publishing world (victims)? It may seem a slight and meaningless distinction, but it powerfully affects your outlook and how you decide what to do next—if you believe you are the person who has control of your life and work.

Also, we have to remember that when one area of the network or community suffers, it will invariably affect another part. (Watch this terrific video on this concept.) We’re already seeing shifts in the market that point to how publishers have to change—e.g., 25% of the top 100 books on Amazon last year were self-published, authors are successfully crowdfunding new books, and Wattpad has launched the careers of new, young authors, which uses a very different model than any we’ve seen before.

New business models are out there, and authors are finding the opportunities amidst the change. Benjamin Zander wrote in The Art of Possibility:

The frames our minds create define—and confine—what we perceive to be possible. Every problem, every dilemma, every dead end we find ourselves facing in life, only appears unsolvable inside a particular frame or point of view. Enlarge the box, or create another frame around the data, and problems vanish, while new opportunities appear.

What frame are we using to look at the economic problem writers now face? I would suggest it’s not useful to use the framework of, “Publishers are taking advantage of writers.” Let’s change the frame we’re using—not to whitewash any potential unethical behavior, but to spot a productive way forward.

One of the more inspiring things I’ve read lately is Elizabeth Hyde Steven’s Make Art Make Money, which is all about balancing business and art, as mastered by the late, great Jim Henson. I can’t think of a better way to close than quote something she learned from studying his career:

We can walk into the world of business feeling we are on the turf of strangers, possible enemies. Or we can enter that world in a way that brings our own turf with us, so that we no longer feel defensive but expansive. With the realization of the power our art wields, we can become generous. When we do, we become compelling, enviable, impressive, and we have the ability to change things.

For more reading on the disruption in publishing:

Book: A Futurist’s Manifesto

What Is the Business of Literature? by Richard Nash

A best reading and authority list I created after participating in a “future of the book” collaborative writing process at Frankfurt Book Fair

The post Are There Limits to Literary Citizenship? appeared first on Jane Friedman and was written by Jane Friedman.

April 17, 2014

Why Are Romance Authors Better at Marketing & Promotion? [Smart Set]

Welcome to The Smart Set, a weekly series where I discuss some of the most interesting questions being raised by astute minds in writing, publishing, and media.

“To seek: to embrace the questions, be wary of answers.”

—Terry Tempest Williams

Today’s edition is abbreviated since I’m at PubSmart in Charleston, SC.

Female Authors Dominating Smashwords Bestseller Lists by Mark Coker

The founder and CEO of Smashwords, Mark Coker, recently realized that his author bestseller list is dominated by women. In fact, for the last four months, the list of Top 25 Smashwords-distributed ebooks were by 100% women.

Factors at work:

Romance is the No. 1 bestseller genre at Smashwords.

Romance is written primarily by women (or by men with female pen names).

Also, and Coker mentions this, romance authors kick ass at marketing and promotion—and have always been better at it than authors in other genres.

On other bestseller lists, particularly traditional publishing bestseller lists, you won’t find such a high percentage of women. It tends to be 50-50 or 60-40 in favor of men.

Questions raised:

Assuming the Smashwords stats are meaningful, are women writers better at self-publishing than men—perhaps better at the marketing and promotion required?

Why are romance authors so much better at marketing and promotion, and can other authors be more like them? Or is it too genre-specific to be widely applicable? I recently spoke on a panel at the Virginia Festival of the Book—focused on romance writers and readers—and this was the theme. Why should romance authors be more progressive and successful in using new tools and digital media to reach readers and sell books? I’m not sure if we came up with a definitive answer.

What questions do you have? Share in the comments.

The post Why Are Romance Authors Better at Marketing & Promotion? [Smart Set] appeared first on Jane Friedman and was written by Jane Friedman.

April 16, 2014

Writing & Money: A Brief Syllabus

For my upcoming keynote talk at The Muse & The Marketplace, I’ve been immersing myself in histories of publishing and the evolution of authorship. While I’m quite well-read on what the future holds (see a separate reading list here), and often speak on the current digital-era disruption, I’ve always wanted a more cohesive understanding of how we’ve arrived at our current model of professional authorship. I’m also reading up on the tension between art and business, and finding that the ability of writers to earn a living through their creative work is a fairly new phenomenon, dating back to the 18th century and the rise of literacy, which largely made professional authorship possible.

We’re a long way from the 18th century, of course. Today writers face a challenging dynamic of supply and demand: you can find writing and publishing in abundance—anybody and everybody can write and publish—but attention is scarce. Thus it’s little surprise that we have writers being paid in exposure, not dollars.

My talk on May 3 will explore these issues in detail, and offer some humor and inspiration along the way. In the meantime, I thought I’d share some of the most illuminating texts I’ve been reading.

Authors & Owners by Mark Rose explores the invention and history of copyright, which has made it possible for writers to make a living from their work. Writers went for more than 250 years after the invention of the printing press without any formal rights to their creations. How did they earn money? Some didn’t—nor did they want to.

The Author, Art, and Market by Martha Woodmansee is an incredible scholarly work that explores what happened as literature became subject to the laws of the market economy, and shows how and when Western culture began to identify art as something that doesn’t sell—and then turned that quality into a virtue.

The Content Machine by Michael Bhaskar is primarily about where publishing is headed, but his theory is grounded in stories of where publishing has been, and traces important historical milestones of the industry.

The Gift by Lewis Hyde came out more than 30 years ago, and is still in print. It’s said that Margaret Atwood gave a copy to every artist she knew when it released. While not focused on publishing, it explores the tension between art and commerce—or how one can or should go about making a living through one’s art.

Make Art Make Money by Elizabeth Hyde Stevens is like a contemporary update to The Gift, using Jim Henson’s career and values to present a framework for creating your art and making a living, but not selling out. Maria Popova writes about it elegantly here.

This is definitely the most exciting presentation I’ve ever had a chance to research and develop, and I’m immensely grateful to Grub Street for inviting me to speak. I hope to see you there.

Note: While my talk is part of the official conference schedule at The Muse, it is also free to the public. If you’re in the Boston area, mark your calendar!

The post Writing & Money: A Brief Syllabus appeared first on Jane Friedman and was written by Jane Friedman.

April 11, 2014

The Complete Guide to Query Letters That Get Manuscript Requests

by Oberazzi / via Flickr

The stand-alone query letter has one purpose, and one purpose only:

To seduce the agent or editor into reading or requesting your work.

The query is so much of a sales piece that you should be able to write it without having written a single word of the manuscript. For some writers, it represents a completely different way of thinking about your book—it means thinking about your work as a marketable commodity. To think of your book as a product, you need to have some distance to see its salable qualities.

Before you begin the query process, have a finished and polished manuscript ready to go. It should be the best you can make it. Only query when you’d be comfortable with your manuscript appearing as-is between covers on a major chain bookstore shelf.

This post focuses on query letters for novels; nonfiction books will be addressed in a different (and future) post.

The 5 Elements of a Novel Query

Every query should include these five elements, in no particular order (except the closing):

Personalization: where you customize the letter for the recipient

What you’re selling: genre/category, word count, title/subtitle

Hook: the meat of the query; 100-200 words is sufficient for a novel

Bio: sometimes optional for uncredited fiction writers

Thank you & closing

This post elaborates on each of those elements—keep reading!

What’s in the very first paragraph of the query?

This varies from writer to writer and from project to project. You put your best foot forward—or you lead with your strongest selling point. Common ways to begin a query:

You’ve been vouched for or referred by an existing client of the agent’s—or if you’re querying a publisher, you might be referred by one of their authors.

You met the agent/editor at a conference or pitch event where your material was requested (in which case, your query letter doesn’t carry much of a burden).

You heard the agent/editor speak at a conference or you read something they wrote that indicates they’re a good fit for your work.

You start with your hook—a compelling hook, of course.

You mention excellent credentials or awards, e.g., you have an MFA from a school that an agent is known to recruit clients from, you’ve won first prize in a national competition with thousands of entrants, or you have impressive publication credits with prestigious journals or New York publishers.

Many writers don’t have referrals or conference meetings to fall back on, so usually the hook becomes the lead for the query letter. Some writers start simple and direct, which is fine: “My [title] is an 80,000-word supernatural romance.”

Personalizing the query: why it makes a difference

Remember, your query is a sales tool, and good salespeople develop a rapport with the people they want to sell to, and show that they understand their needs. Show that you’ve done your homework, show that you care, and show that you’re not blasting indiscriminately.

Will you be automatically rejected for not personalizing your query? No, but if you do take the trouble to personalize it, you’ll set yourself apart from the large majority of writers querying, and that’s the point.

Example of a strong, personalized lead

In a January interview at the Guide to Literary Agents blog, you praised The Thirteenth Tale and indicated an interest in “literary fiction with a genre plot.” My paranormal romance Moonlight Dancer (85,000 words) blends a literary style with the romance tradition.

The 3 Elements of a Novel Hook

For most writers, it’s the hook that does most of the work in convincing the agent/editor to request your manuscript. You need to boil down your story to these three key elements:

Protagonist + his conflict

The choices the protagonist has to make (or the stakes)

The sizzle

Some genres/categories should add a fourth element: the setting or time period.

What does “sizzle” mean? It’s that thing that sets your work apart from all others in the genre, that makes your story stand out, that makes it uniquely yours. Sizzle means: This idea isn’t tired or been done a million times before.

How do you know if your idea is tired? Well, this is why everyone tells writers to read and read and read. It builds your knowledge and experience of what’s been done before in your genre, as well as the conventions.)

When a hook is well written but boring, it’s often because it lacks anything fresh. It’s the same old formula without distinction. The protagonist feels one-dimensional (or like every other protagonist), the story angle is something we’ve seen too many times, and the premise doesn’t even raise an eyebrow. The agent or editor is thinking, “Sigh. Another one of these?”

This is the toughest part of the hook—finding that special je ne sais quois that makes someone say, “Wow, I’ve got to see more of this!” And this is often how an editor or agent gauges if you’re a storyteller worth spending time on.

Sometimes great hooks can be botched because there is no life, voice, or personality in them.

Sometimes so-so hooks can be taken to the next level because they convey a liveliness or personality that is seductive.

You want to be one of those seductive writers, of course.

Hook Construction

You have a few options; these are the most common ways to build the hook.

“I have a completed [word count][genre] titled [title] about [protagonist name + small description] who [conflict].”

Answer these questions: What does your character want? Why does he want it? What keeps him from getting it?

[Character name + description] + [the conflict they’re going through] + [the choices they have to make].

Whenever I teach a class where we critique hooks, just about everyone can point out the problems and talk about how to improve them. Why? Because when you’re not the writer, you have distance from the work. When you do come across a great novel hook, it feels so natural and easy—like it was effortless to write.

But great novel hooks are often toiled over. To convey a compelling story in just a few words is the test of a great writer.

I often recommend brevity when writing the hook, especially if you lack confidence. Brevity gets you in less trouble. The more you try to explain, the more you’ll squeeze the life out of your story. So: Get in, get out. Don’t labor over plot twists and turns.

Examples of brief hooks

Every day, PublishersMarketplace lists book deals that were recently signed at major New York houses. It identifies the title, the author, the publisher/editor who bought the project, and the agent who sold it. It also offers a one-sentence description of the book. These hooks are inevitably well-crafted, and can help you better understand what hooks really excite agents/publishers. While your hook would/should probably get into more detail than the following two examples, these hooks help illustrate how much you can accomplish in just a line or two.

Bridget Boland’s DOULA, an emotionally controversial novel about a doula with a sixth sense [protagonist] who, while following her calling, has to confront a dark and uncertain future when standing trial for the death of her best friend’s baby [protagonist's problem] [a doula with a sixth sense? cool.]

John Hornor Jacobs’s SOUTHERN GODS, in which a Memphis DJ [protagonist] hires a recent World War II veteran to find a mysterious bluesman whose music [protagonist's problem] — broadcast at ever-shifting frequencies by a phantom radio station — is said to make living men insane and dead men rise [twist]

Check for red flags in your novel hook

How to tell if your hook could be improved:

Does your hook consist of several meaty paragraphs, or run longer than 200 words? You may be going into too much detail.

Does your hook reveal the ending of your book? Only the synopsis should do that.

Does your hook mention more than three or four characters? Usually you only need to mention the protagonist(s), a romantic interest or sidekick, and the antagonist.

Does your hook get into minor plot points that don’t affect the choices the protagonist makes? Do you really need to mention them?

The Key Elements of Your Bio

For novelists, especially unpublished ones, you don’t have to include a bio in your query if you can’t think of anything worth sharing. But it’s nice to put in something.

The key to every detail in your bio is: Will it be meaningful—or perhaps charming—to the agent/editor? If you can’t confidently answer yes, leave it out. In order of importance, these are the categories of pertinent info.

Publication credits

Be specific about your credits for this to be meaningful. Don’t say you’ve been published “in a variety of journals.” You might as well be unpublished if you don’t want to name them.

What if you have no fiction writing credits? Should you say you’re unpublished? No. That point will be made clear by fact of omission.

Many novelists wonder if it’s helpful to list nonfiction credits. Yes, mention notable credits when they show you have some experience working with editors or understanding how the professional writing world works. That said: Academic or trade journal credits can be tricky, since they definitely don’t convey fiction writing ability. Use your discretion, but it’s probably not going to be deal breaker either way.

Online writing credits can be just as worthy as print credits. Popular and well-known online journals and blogs count!

Leave out credits like your church newsletter or credits that hold little to no significance for the publishing industry professionals.

Should you mention self-published books?

That’s totally up to you. Sooner or later this information will have to come out, so it’s usually just a matter of timing. Lots of people have done it, and it doesn’t really hurt your chances. If you do mention it, it’s best if you’re proud of your efforts and are ready to discuss your success (or failure) in doing it. If you consider it a mistake or irrelevant to the project at hand, leave it out, and understand it may come up later.

Do not make the mistake of thinking your self-publishing credits make you somehow more desirable as an author, unless you have really incredible sales success, in which case, mention the sales numbers of your book and how long it’s been on sale.

Work/career

If your career or profession lends you credibility to write a better story, by all means mention it. But don’t go into lengthy detail. Teachers of K-12 who are writing children’s/YA often mention their teaching experience as some kind of credential for writing children’s/YA, but it’s not, so don’t treat it like one in the bio. (Perhaps it goes without saying, but parents should not treat their parent status as a credential to write for children either.)

Writing credibility

It makes sense to mention any writing-related degrees you have, any major professional writing organizations you belong to (e.g., RWA, MWA, SCBWI), and possibly any major events/retreats/workshops you’ve attended to help you develop your career as a writer.

You needn’t say that you frequent such-and-such online community, or that you belong to a writers’ group the agent would’ve never heard of. (Mentioning this won’t necessarily hurt you, but it’s not proving anything either.)

Avoid cataloguing every single thing you’ve ever done in your writing life. Don’t talk about starting to write when you were in second grade. Don’t talk about how much you’ve improved your writing in the last few years. Don’t talk about how much you enjoy returning to writing in your retirement.

Just mention 1 or 2 highlights that prove your seriousness and devotion to the craft of writing. If unsure, leave it out.

Special research

If your book is the product of some intriguing or unusual research (you spent a year in the Congo), mention it. These unique details can catch the attention of an editor or agent.

Major awards/competitions

Most writers should not mention awards or competitions they’ve won because they are too small to matter. If the award isn’t widely recognizable to the majority of publishing professionals, then the only way to convey the significance of an award is to talk about how many people you beat out. Usually the entry number needs to be in the thousands to impress an agent/editor.

Charming, ineffable you

If your bio can reveal something of your voice or personality, all the better. While the query isn’t the place to digress or mention irrelevant info, there’s something to be said for expressing something about yourself that gives insight into the kind of author you are—that ineffable you. Charm helps.

It’s okay to say nothing at all about yourself

If you have no meaningful publication credits, don’t try to invent any. If you have no professional credentials, no research to mention, no awards to your name—nothing notable at all to share—don’t add a weak line or two in an attempt to make up for it. Just end the letter. You’re still completely respectable.

Don’t bother mentioning these things

Unless you know the agent/editor wants to hear about these things, you don’t need to discuss (for novelists, remember, not nonfiction writers):

Your social media presence

Your online platform

Your marketing plan

Your years of effort and dedication

How much your family/friends love your work

How many times you’ve been rejected or close accepts

Sometimes you might mention your website or blog, especially if you feel confident about its presentation. The truth is the agent/editor is going to Google you anyway, and find your website/blog whether you mention it or not (unless you’re writing under a different name). Keep in mind that having an online presence helps show you’ll likely be a good marketer and promoter of your work—especially if you have a sizable readership already—but it doesn’t say anything about your ability to write a great story. That said, if you have 100,000+ fans/readers on Wattpad or at your blog, that should be in your query letter.

Example of a solid bio

A professional writer for more than 30 years, I’ve had short stories published in literary journals such as Toasted Cheese, Long Story Short, and Beginnings. My first novel manuscript was a finalist for a James Jones Fellowship. I am co-founder and editor of the online literary journal Cezanne’s Carrot, and also write the blog Writers In The Virtual Sky.

Close your letter professionally

You don’t read much advice about how to close a query letter, perhaps because there’s not much to it, right? You say thanks and sign your name. But here’s how to leave a good final impression.

You don’t have to state that you are simultaneously querying. Everyone assumes this. (I do not recommend exclusive queries; send queries out in batches of three to five—or more, if you’re confident in your query quality.)

If your manuscript is under consideration at another agency, then mention it if/when the next agent requests to see your manuscript.

If you have a series in mind, this is a good time to mention it. But don’t belabor the point; it should take a sentence.

Never mention your “history” with the work, e.g., how many agents you’ve queried, or how many near misses you’ve suffered, or how many compliments you’ve received on the work from others.

Resist the temptation to editorialize. This is where you proclaim how much the agent will love the work, or how exciting it is, or how it’s going to be a bestseller if only someone would give it a chance, or how much your kids enjoy it, or how much the world needs this work.

Thank the agent, but don’t carry on unnecessarily, or be incredibly subservient—or beg. (“I know you’re very busy and I would be forever indebted and grateful if you would just look at a few pages.”)

There’s no need to go into great detail about when and how you’re available. Make sure the letter includes, somewhere, your phone number, e-mail address, and return address. (Include an self-addressed stamped envelope for snail mail queries.) I recommend putting your contact info at the very top of the letter, or at the very bottom, under your name, rather than in the query body itself.

Do not introduce the idea of an in-person meeting. Do not say you’ll be visiting their city soon, and ask if they’d like to meet for coffee. The only possible exception to this is if you know you’ll hear them speak at an upcoming conference—but don’t ask for a meeting. Just say you look forward to hearing them speak. Use the conference’s official channels to set up an appointment if any are available.

Query Letter Red Flags

Here is an overall list of red flags to look for in your query letter.

If it runs longer than 1 page (single spaced), you’ve said too much.

If your novel’s word count is much higher than 100,000 words, you have a much bigger challenge ahead of you. Eighty thousand words is the industry standard for a debut novel. See this post for a definitive list of appropriate word counts by genre.

Ensure you’ve specified your genre, without being on the fence about it.

Avoid directly commenting on the quality of your work. Your query should show what a good writer you are, rather than you telling or emphasizing what a good writer you are.

On the flip side: Don’t criticize yourself, or the quality of the work, in the letter.

Don’t editorialize your story for the agent/editor, almost as if you were writing a review of the work. (“In this fast-paced thriller,” “in a final twist that will change your world,” “you’ll laugh, you’ll cry, …”

Do not explain how or why you came to write the story, unless it is really interesting or integral to the work.

Do not talk about how you’ve wanted to write since you were a child.

Do not talk about how much your family and friends love your work.

Avoid heavy use of adjectives, adverbs, and modifiers. In fact, try creating a version of your query without any modifiers, and see what happens.

When it comes to selling fiction, you don’t have to talk about the trends in the market, or about the target audience. You sell the story. (However, for nonfiction queries, you do talk about trends and market, which is why some writers are confused over this point.)

Tell me more about exclusives—what are they?

This is when an agent responds positively to your query and asks for an exclusive read on your manuscript. That means no one else can read the manuscript while they’re considering it. I don’t recommend granting an exclusive unless it’s for a very short period (maybe 2 weeks).

In non-exclusive situations (which should be most situations): If you have a second request for the manuscript before you hear back from the first agent, then as a courtesy, let the second agent know it’s also under consideration elsewhere (though you needn’t say with whom). If the second agent offers you representation first, go back to the first agent and let her know you’ve been made an offer, and give her a chance to respond.

Should I compare my book to another title, or compare myself to another author?

This can be helpful as long as you do it tastefully, and without self-aggrandizement. It’s usually best to compare the work in terms of style, voice, or theme, rather than in terms of sales, success, or quality.

Is it better to query via e-mail, if allowed?

Yes. E-mail can lead to faster response times. However, I’ve heard many writers complain that they never receive a response. (Sometimes silence is the new rejection.) This is a phenomenon that must be regrettably accepted. Send one follow-up to inquire, but don’t keep sending e-mails to ascertain if your e-query was received.

How can I format the e-mail query properly?

Write your query in Word or TextEdit. Strip out all formatting. (Usually there is an option under “Save As” that will allow you to save as simple text.)

Send the query without any formatting and without any indents (block style).

Use CAPS for anything that would normally be in italics.

Don’t use address, date headers, or contact information at the beginning of the e-mail; put all of that stuff at the bottom, underneath your name.

The first line should read: “Dear [Agent Name]:”

Some writers structure their e-queries differently than paper queries (or make them shorter). Consider how much the agent can see of your e-query on the first screen, without scrolling. That’s probably how far they will read before responding or hitting delete. Adjust your query accordingly. Usually the hook should go first, unless you have a strong personalization angle.

I have an e-mail address for an editor/agent who doesn’t accept e-mail queries. Should I try them anyway?

You can try, but you probably won’t receive a response.

How soon can I follow up if I don’t hear back?

Try following up about 2-4 weeks after the stated response time. If no response time is given, wait a couple of months. If querying via snail mail, include another copy of the query. If you still don’t hear back after one follow-up attempt, assume it’s a rejection, and move on. Do not phone or visit.

Is it OK to tell agents/editors to visit my website for more info?

Avoid this. Agents should have all the information they need to make a decision right in your query letter. (Of course, most of them will Google you anyway and check out your online presence to get a sense of how you might be to work with.) It’s OK to list your website or blog as part of your contact info; just don’t tell agents in the body of the query to visit your site for more info, or to read your book at your site.

Should I send a synopsis with the query?

Only if requested in the submission guidelines. Click here for instructions on how to write a synopsis.

More resources on query letters

QueryShark (opportunity to get your query critiqued + read others critiqued)

AgentQuery

Agent Rachelle Gardner’s post on query letters

Former agent Nathan Bransford’s guide to query letters

How to identify agents to query

PublishersMarketplace (for in-depth info on agents and publishing deals, costs $25/month)

WritersMarket.com (requires monthly or annual subscription)

AgentQuery: a free online resource

Don’t forget to look at agency websites (as you begin to select and customize your queries and submissions for each agent appropriate for your work)

Looking for more?

Start Here: How to Get Your Book Published

Start Here: How to Write a Book Proposal

Back to Basics: Writing a Novel Synopsis

Perfecting Your First Page [especially helpful if you're sending the first 1-5 pages along with your query]

Need one-on-one help?

Check out my Query Letter Critique Service.

The post The Complete Guide to Query Letters That Get Manuscript Requests appeared first on Jane Friedman and was written by Jane Friedman.

April 10, 2014

Is Publishing in Trouble or Not—Decide! [Smart Set]

Welcome to The Smart Set, a weekly series where I discuss some of the most interesting questions being raised by astute minds in writing, publishing, and media.

“To seek: to embrace the questions, be wary of answers.”

—Terry Tempest Williams

Tom Weldon: “Some Say Publishing Is in Trouble. They Are Completely Wrong.” by Jennifer Rankin (The Guardian)

This one was tweeted and shared a lot; it’s a catchy headline. Whenever such a strong statement is made and publicized like that, it sets off a couple alarms: (1) It’s probably in reaction to someone or something, and (2) it’s not leaving much room for nuance.

Completely wrong? Let’s take a closer look at the supporting evidence, provided by UK chief executive Tom Weldon of Penguin Random House:

In the last four years, Penguin and Random House have had the best years in their financial history.

Book publishers have managed the digital transition better than any other media or entertainment industry.

The size of Penguin Random House is mentioned as an advantage when moving into multimedia areas such as apps, games, and other entertainment tied into books.

Weldon says, “Eight to nine months in, things are going extremely well. We had our best results. We consistently publish bestsellers.”

Penguin Random House publishes 200 to 250 debut writers every year. “I can’t think of any other cultural institution that sponsors new art in the same way,” Weldon says.

Questions raised:

If Penguin and Random House have had their best years in their financial history, where is that growth coming from? Are more units being sold? Are the units being sold at a higher price? Are more titles being produced overall? Does it relate to ebook sales growth—and the fact ebook sales are more profitable for publishers due to the lower author royalty rate? Is it non-book sales?

How meaningful is it that book publishers seem to have managed the digital transition better than other industries? Is that true? And is it comparing apples and oranges?

What are the potential drawbacks to a publisher the size of Penguin Random House? The article mentions how this might reduce competition for new works and decrease the size of advances.

Is Penguin Random House publishing more debut authors than ever before, or is the number fairly stable (or declining)? How many debut authors go onto second book deals?

London Book Fair 2014: PW Talks With Kobo President Michael Tamblyn by Andrew Albanese (Publishers Weekly)

Kobo is one of the ebook devices and retailers that continues to compete against Amazon. It’s known for having a solid share of the Canadian market (it’s based in Toronto) and a strong international footprint (it is owned by Rakuten in Japan).

This interview with Tamblyn has a few gems in it, including the following, where he’s asked about the impact of self-publishing to Kobo’s bottom line:

It’s become a very significant piece of the business for us. It is now quite easily 10% or 11% of unit sales on any given day. That means self-publishing in any given country is a big five publisher, if you look at it weight for weight. In the aggregate, it has become a significant force, I’d say a transformative force when we look at authors and their relationship to publishers. Authors now know this other means is available to them and that in turn has made publishers step up their game. To me, this is kind of the Golden Age of the author, and we’re happy to help move that along.

Questions raised:

If it’s 10-11% percent of unit sales, what’s the percentage in dollars, given that self-publishing titles are often priced lower? (You can find much more speculation about this over at Mike Shatzkin’s blog. It might be reasonable to speculate the dollars would be at 5-6%.) As an interesting side note, I’ve heard reports from self-published authors that their ebooks on Kobo can command a higher price point because the readership is more upmarket, and haven’t been trained, as Amazon customers have, to surf for free/cheap ebooks.

And wouldn’t we all love to know these figures for Amazon, Apple’s iBookstore, and Barnes & Noble’s Nook? Hugh Howey’s estimates over at AuthorEarnings.com put the figure at 27% of units sold are indie. If you’ve seen additional figures somewhere, please comment.

How much more will this percentage grow, and how much will it grow at the expense of traditionally published titles?

Compare and contrast this with the above article claiming that publishers are totally and completely not in trouble.

Publishers Are Warming to Fan Fiction, But Can It Go Mainstream? by Rachel Edidin (Wired)

For the past couple years, I’ve worked in the literary publishing world, which is largely ignorant of the enormity of writing and reading that happens on fan-fiction community sites. This article at Wired discusses some new initiatives to harness the writers and community around fan-fiction, and turn it into something monetizable; it argues that the lines between fan-fiction and other types of writing are beginning to blur.

Questions raised:

How big of a role will fan fiction play in the future of publishing?

Are communities like Wattpad and Archive of Our Own—which operate primarily outside of the traditional publishing economy—closer to what authorship will look like in the future?

What questions (or answers) do you have? Share in the comments.

By the way: Don’t miss my interview with the Late Night Library, where I discuss the economics of being a writer in the digital age, along with by Scratch co-founder, Manjula Martin.

The post Is Publishing in Trouble or Not—Decide! [Smart Set] appeared first on Jane Friedman and was written by Jane Friedman.

April 4, 2014

Make Submitting Work Your Superpower

Over at the latest Glimmer Train bulletin, writer David James Poissant discusses a topic very near and dear to my heart:

Grit. Or maybe you call it persistence. He calls it relentlessness and tenacity.

It goes by a lot of names, but basically it means a few rejections aren’t going to stop you. Or just because you didn’t get your novel published at age 30, you decide you’re all washed up.

Poissant writes:

Perhaps, for some writers, publications and acclaim come easy, but I’m not one of those writers, nor do I know any. No magazine or editor has ever come to my door and knocked and asked if I had a story or novel sitting around that needed publishing. I say this, and you nod. But, you’d be surprised by how often students or beginning writers complain about not being published or about the difficulty of placing work before confessing that they don’t really send their work out, or that they’ll send a story to three or four literary magazines before giving up on it.

In my experience, it’s not the ones with talent who make it. It’s the ones who keep at it, even when things are going horribly wrong.

Get more inspiration over at Glimmer Train’s latest bulletin:

The Apprentice by Lee Montgomery

Using The Writer’s Notebook: A Practical Guide by Lisa Catherine Harper

The post Make Submitting Work Your Superpower appeared first on Jane Friedman and was written by Jane Friedman.

April 3, 2014

The Future of Hybrid Authors + Who Influences Our Purchases [Smart Set]

Welcome to The Smart Set, a weekly series where I discuss some of the most interesting questions being raised by astute minds in writing, publishing, and media.

“To seek: to embrace the questions, be wary of answers.”

—Terry Tempest Williams

Must a Writer Go Hybrid for Higher Income? by Elizabeth Spann Craig

Established author—and longtime blogger in the writing community—Elizabeth S. Craig writes that, as of 2013, her self-published books are earning more money than her books with Penguin. She then lists the benefits of having a traditional publisher, and says those benefits for her are “winding down.”

Questions raised:

Like many hybrid authors, Craig established her readership in part by having a traditional publisher, and now she can reach that readership directly on her own. How many authors have the temperament of Craig and will decide that once their readership is established, their publishers don’t offer enough value? (I should note here that a strong commercial fiction factor is in play; genre fiction enjoy the best e-book sales because their reader numbers and consumption are high. Literary fiction authors really aren’t going to be asking these questions, not for a long time.)

What is the likelihood that publishers will raise e-book royalty rates in light of the above? What other ways could they remain attractive?

What if Amazon decides to drop their royalty rate from 70% to 35%? Will publishers become more attractive?

Newspapers Are Dead: Long Live Journalism by Ben Thompson

This is the third part in an excellent series at Stratechery discussing the future of news, journalism, and newspapers. While many would like to believe that “quality” will win the day, Thompson provocatively points out that quality journalism is largely irrelevant to the financial well-being of news organizations. It’s not all doomsday, however; Thompson points out the silver lining, primarily that there’s still a (large) audience for journalism, and every writer out there has the potential to reach that audience with free distribution and sharing tools. He offers up potential business models for the future, which are ripe for debate.

Questions raised:

How much journalism in the future will happen through big organizations/corporations versus individuals or small endeavors?

How quickly and how successfully will journalism transition to subscription- and reader-based revenue models rather than advertising models? How quickly will advertising plummet for legacy news orgs—and is native advertising a stop-gap measure rather than a long-term solution?

How will business models differ between the general-interest news gathering operations versus niche/specialized areas? It seems quite easy to predict the success of subscription-based models around special-interest areas, or topics with high value to the reader (financial and business news, for example). Perhaps general-interest news gathering or news brands will dwindle down to a handful of big, influential brands, e.g., The New York Times and The New Yorker?

US Consumers’ Biggest Purchase Influencers by Marketing Charts

I discovered this through Peter McCarthy’s Twitter feed (@petermccarthy)—a great follow for any author who’s interested in digital marketing.

The graph you’ll find at the link confirms some of what we already know: word of mouth is the No. 1 influencer of purchases. What’s more interesting and maybe surprising is how the rest of the list stacks up:

“An online review by someone you do not know in real life” ranks several influence points higher than a magazine ad.

Ads delivered by social media platforms are near the bottom of the influence list, only beating out video game advertising and a text-message ad (the worst purchase influencer).

An e-mail from a company or brand ranked below newspaper ad, but above radio and in-theater advertising.

Questions raised:

I would love to see how this chart may have changed over time. Has social media advertising gone up or down in these rankings? Have traditional media ads declined over time? I couldn’t find any comparison data.

What questions (or answers) do you have? Share in the comments.

The post The Future of Hybrid Authors + Who Influences Our Purchases [Smart Set] appeared first on Jane Friedman and was written by Jane Friedman.

April 1, 2014

On Being a Writer With Skin in the Game

Untitled Blue / via Flickr

Today’s guest post is by author L.L. Barkat (@llbarkat).

“Why don’t you like to talk about your writing?” I asked. “I mean, you’re not writing erotica or something, are you?”

I was taking a business contact out for tea. I was kidding.

But, moments later I discovered I was right. This is exactly why my contact was shy to discuss her writing. Unbeknownst to me, I was taking a fairly well-known erotica writer to tea, albeit under her real name.

Well.

There’s a part of me that is not completely comfortable talking about my writing either, and for similar reasons: the best of it is highly personal, even as it is universal. There is, as they say, skin in the game, and it feels a little exhibitionistic to discuss it. I have a poem in my new collection, Love, Etc., that deals with this question of the how far the writer must go, and the poem disturbs me. Here is an excerpt.

The canes were stripped,

and maybe you will see

a woman in them, or your

very soul, and you will wish

you were a stripper,

no longer holding out

on the world…

Of course, I did not need to put the poem in the collection. Who would have been the wiser if I left it out? But I put it in, because part of what I am struggling to express in the collection is the uneasy pact the writer (and later, the writer-as-marketer) makes with the world: yes, come see I’ve got skin in the game.

I say “uneasy” because there is such a delicate balance. Push too far, and you are the next “raw, authentic” writer who is really just manipulating the crowd with too much information. (Better to save that for Snapchat and let the record disappear.) Don’t push far enough, and you are holding out on the world, and the reader knows instinctively there’s nothing worth staying for.

Does it matter?

I think it does, and not just from an artistic standpoint.

The sheer volume of materials available to today’s readers means that they will need to begin to make more and more choices. Time constraints, fatigue, and economics will compel them to do so.

Best, then, to think long term as a writer.

My erotica-writing contact exhausted herself pretty quickly. It was not an easy life, not terribly sustaining (although she says she had fun for a while). Compare this to a writer like Rebecca Solnit, whose book The Faraway Nearby we read just together as a community, at the site I manage. The Faraway Nearby is Solnit’s thirteenth book, and I am not sure she had fun at all, writing it, but it is a beauty that will have staying power.

As many writers do, I am now speaking to myself as much as I am to you. I am encouraging us to remember that writing is something to take the long view over, developing ourselves into the kind of writers that readers can trust for openness that isn’t just sensationalism—and for quality that will be worth their continued time, attention, and dollars.

What’s your plan for doing so?

The post On Being a Writer With Skin in the Game appeared first on Jane Friedman and was written by L.L. Barkat.

March 27, 2014

The Ebook Market + Big Five Survival [Smart Set]

Today marks the beginning of a new weekly series, The Smart Set, where I discuss some of the most interesting questions being raised by astute minds in writing, publishing, and media. I use the word “questions” quite purposefully, because I prefer the mission of seeking, or as Terry Tempest Williams says:

To seek: to embrace the questions, be wary of answers.

Let’s seek together. I hope you enjoy, and don’t hesitate to send me tips via my contact page.

Has Everyone Conceded the U.S. E-Book Market to Amazon? by Jane Litte at Dear Author

Amazon Kindle, which already comprises 50-70% of the U.S. ebook by most estimates, may soon increase that share dramatically, due to lack of competition. Both Barnes & Noble’s Nook and Kobo have reduced their marketing resources and/or commitment to the U.S. market. As Litte explains, that leaves Google and Apple iBooks, the latter of which is only available to Mac/iOS users.

Questions raised:

If Amazon increases its dominance in the ebook market, as expected, will they ultimately reduce royalties to Amazon KDP authors, as they’ve done through their audiobook division? How much will profitability of authors be affected?

If Amazon gains more market share than they already have, how will this affect book discoverability and sales for the overall book industry , especially if they prioritize their own publishing imprints?

Can and will another worthy competitor arise in the next few years?

Everybody Wants a Netflix for Books by Joseph Esposito

E-book subscription services have been getting a lot of attention in recent months. You may have heard about some of the start-ups: Oyster is among the most high-profile and recent launches, while Scribd has been around a lot longer.

Publishing industry vet and consultant Joseph Esposito writes an insightful post that reminds us that the Netflix streaming service is not a true all-you-can-eat or comprehensive model. It does not offer some of the most popular shows (Game of Thrones, for instance), and there are huge gaps in its offerings, unlike its DVD service. Esposito has very firm conclusions, which I’ll let you read yourself.

Questions raised:

Most publishers/authors/agents do not see the benefit to having their books included in subscription services, thus the services aren’t truly comprehensive, which would help them attract subscribers. Under what conditions could these subscription services become attractive enough that successful authors/publishers/agents want to play?

How can these services survive in the long term, considering they currently have to bet on the “gym membership” model to remain profitable? (Users have to read fewer books if their monthly fee is to cover the royalties paid to publishers/authors.)

You can read more from the agent perspective on these services at the AAR blog, by Brian DeFiore.

What Penguin Random House Isn’t Doing by Philip Jones

The FutureBook blog (run by The Bookseller magazine, based in the UK) reports that Penguin-Random House UK is not doing many of the things advocated for publishers nowadays, such as selling direct to readers or rebranding itself. (PRH has more than 50 imprints in the UK.) But, he says, they also seem to be doing just fine without transforming their business. “This is a collection of businesses that was never broke, and not in need of a fix,” he writes.

Meanwhile, Mike Shatzkin, a U.S.-based publishing expert, emphasizes (and points to articles that show) that Penguin-Random House has made moves to become a consumer-focused publisher, trying to build a direct relationship with readers. He then discusses, big picture, the challenge of every publisher with dozens of imprints that hold little to no weight with the consumer:

Each major house should pick one name that is an umbrella. It goes on every book to establish the company as a major source of quality literature, enjoyable reading, and book-packaged information. Trying to target more precisely than that should be the job of the “imprint” brand under the umbrella brand. And that brand should be vertical, identifying subject or audience.

Basically, we’re talking about an enormous rebranding effort, with the potential dissolution of many imprint names, and a tighter, more explicit connection between imprint and target market. Think of Harlequin; you probably just pictured a romance novel. That’s the goal. Now, think Tarcher. Did an image come to mind? Probably not. (It’s one of the many imprints of Penguin in the U.S.)

Questions raised:

How much will the Big Five restructure to make their imprints more consumer-driven? And how quickly?

If the Big Five don’t get more “vertical” (focused and targeted) with their imprints, how big is the risk?

How essential is it for the Big Five (and all publishers) to sell direct to readers for long-term survival?

The post The Ebook Market + Big Five Survival [Smart Set] appeared first on Jane Friedman and was written by Jane Friedman.

March 24, 2014

7 Things I Learned from the World’s Best Marketers

Today’s guest post is by author Tiana Warner (@tianawarner).

The Art of Marketing conference in Vancouver was a full day of marketing insight from Seth Godin, Nancy Duarte, Mitch Joel, John Jantsch, Brian Wong, Keith Ferrazzi, and big-name sponsors like Microsoft and CBC. Each highly qualified speaker offered a unique perspective on the current and future state of marketing.

Below are 7 essential takeaways from these world-class marketers, and my thoughts on applying them to the book industry.

1. Find a specific audience

The mass market no longer matters. The bell curve is melting, and more people fall outside of the normal range than inside. Target the ones outside of the normal range (what Seth Godin called the “weird people”).

What’s your niche? Zombie romance? Identify your exact audience. Hit up the place your ideal reader hangs out—both online and in the real world. You must go find your loyal followers.

2. Build a network

Modern marketing is not about broadcasting to anyone and everyone. It’s about building emotional connections with the right people. Create deep, loyal relationships with readers by genuinely caring about them. Be real, be vulnerable.

With those deep relationships in place, your web will start to build itself. It’s Metcalfe’s Law: readers will tell others about your book if they like it, and the value of your network will explode.

Building your network also means connecting with other authors (hi there!) and anyone who can help you market. Make a list of people you’d like to connect with. It might feel fake to approach someone and say, “Hey, I think it’s important we build our relationship.” It’s not. Being intentional about building a relationship doesn’t make it fake. So get out there and network.

3. Lead a tribe

People naturally want to be in a tribe—i.e., a group with a common purpose. What’s your tribe? Find it.

They key word here is find. Find, not create. You don’t need to invent a subculture—you just need to show up to lead it. Someone must become the leader of a tribe, and that someone can be you.

Then lead with generosity, intimacy, candor, and accountability.

4. Earn trust

Build relationships on both a professional and personal level. Earn your market’s trust, because once people trust you, they’ll listen to you.

Market to people who want to be marketed to. Don’t invade their space and privacy. It seems obvious: the most effective way to sell a book is to offer it to someone who is looking for a book to read.

John Jantsch talked about The Marketing Hourglass: Know, Like, Trust, Try, Buy, Repeat, Refer. This is a unified process, and an order of events we all need to remember.

5. Ditch the ads

The internet wasn’t designed for ads like TV, radio, and magazines were. People pay millions of dollars a year to remove ads from their apps and web browsers.

Marketing is no longer about ads. It’s about adding value to peoples’ lives with content. (Unique content for your niche! Remember to avoid that “normal range,” or you’ll find your content competing against Charlie Bit My Finger.)

Seth Godin said one of his early books on the internet was a failure because he saw the internet and tried to make a book. Yahoo, on the other hand, saw the internet and made a search engine. We must think in terms of what works now, and not attempt to mold it into something we’re comfortable with.

6. Be generous

Every speaker talked about generosity. People don’t want to connect with a selfish person. Give away copies, offer valuable content, offer rewards to your advocates.

Would your followers miss you if you didn’t show up tomorrow? The answer should be yes. Offering valuable content is key for your website, blog, and social media platforms.

Be generous without expecting or asking for anything in return. Generosity is the foundation of a strong following.

7. Resonate through story

As mentioned above, sharing valuable content is important to building a following. Use the rules of a story when developing content in order to connect with your audience at an emotional level. Story is the best way to create meaning around a brand.

Write content using a 3-act structure. Have a beginning, middle, and end, with thresholds in between. Establish what’s “at stake” for the audience (your protagonist), and ensure they emerge transformed. You are the intervening mentor who helps the hero get unstuck when they encounter roadblocks along the way. Let your passion show, draw from a range of emotions, and use rhetoric.

People identify more with brands that offer a human connection.

Bonus notes

A few additional notes that I couldn’t bring myself to leave out:

My favorite thought of the day came from Seth Godin: “If failure is not an option, neither is success. The guy who invented the ship also invented the shipwreck.”

Fear is an indication that you’re onto something good. Use it as fuel.

The future is about connecting the physical world to the online world.

We shouldn’t try to stand out of the crowd. The crowd will make us change who we are. The way to stand out is to avoid the crowd altogether.

We live in a one-screen world, where the screen in front of us is the only one that matters. Develop a unified marketing strategy (not one for web, one for mobile, one for tablet.)

What else do you see as the new face of marketing? If you’ve used these principles, have they worked for you?

The post 7 Things I Learned from the World’s Best Marketers appeared first on Jane Friedman and was written by Tiana Warner.

Jane Friedman

- Jane Friedman's profile

- 1882 followers