Marc Weidenbaum's Blog, page 486

September 25, 2012

Junto Byproduction Edit (MP3)

The most recent Disquiet Junto (“Zola’s Foley”) project was about conglomeration, about the creation of a sense of place and space using far-flung source material. It wasn’t one of the more popular of the weekly composition-project series, but it yielded some fine work — not just in the final productions but in the byproduct. Zedkah, who hails from London, put humorous effort into his entry, which imagined a retail space: “Carla Stores is on the outskirts of NE London, accessed by one of the last stops on the Makebelieve line.” And subsequent to posting that, he shared one of the work’s constituent parts, under the title “Creakfoot mix [ for your creative use].”

In the Junto track he noted that “several footmen constantly pace the panel wood reception in a surprisingly rhythmic way.” Here we hear just the pacing itself, as he recorded it for use in his Junto piece. He posted this excerpt with hopes of hearing it sublimated into others’ musical efforts: “This is offered as download to anyone who might like it to do something with it. Would love to hear some musical use of this.” Here’s hoping someone takes him up on it.

Visit Zedkah’s soundcloud.com/zedkah page to download “Creakfoot mix [ for your creative use]“ and his Junto effort that resulted from it.

September 24, 2012

Environment Jamming (MP3)

There are field recordings, and there are field recordings. There are audio documents of the soundscape, and there are regionally indigenous musics archived thanks to portable gear.

And then there are hybrids. There are compositions that make use of the physical environment to perform something tuneful or rhythmic or otherwise musical in real time. Such is “Construction Container” by Joshua Wentz, in which simple percussion prefaces, then aligns with, and overall frames the sound of a passing train. The very brief liner note associate with the track is simply: “Felt mallet on an overturned metal construction container, as the El passes by.” That’s El for elevated train — Wentz is based in Chicago. The distant train is heard coming into sonic view, as it were, though the looming presence may not be self-evident on first listen. It passes quickly, and once it’s passed by, the percussion slows, a denouement that artfully echoes the vehicles diminishing presence.

Wentz track originally posted at soundcloud.com/joshuawentz. More on Wentz at joshuawentz.com.

The urtext of such experiments in realtime environment jamming is arguably “Ear to the Ground” by the great David Van Tieghem, once upon a time a stalwart of the nascent New York downtown scene, and today a major force in theatrical sound design and composition (upcoming projects include August Wilson and Clifford Odets revivals). Here, for reference, is a video of it:

September 23, 2012

The Electronic Voice (MP3)

Miulew is Björn Eriksson, of Sollefteå, Sweden. It’s unclear if his track “Electric Voices in Happy Cloud – experiment 1″ is voice processing or electronic voice phenomena. That is, it is unclear whether it is voices clipped and truncated and splintered and filtered until they sound abstract, or if it is the semblance of voices arising from within electronica’s effluence. Is it noise from signal or signal from noise? Either way, it’s a granular pleasure. Here’s how Eriksson describes it:

So this was a tryout of seeing if I could capture some voice-like sounds in a feedbacked granulator setup. At first I found some rather “voicy” things, but when I started to work deeper onto it I lost it. So this must be considered an experiment more than a worked through track/piece. Anyway; i was rather happy about some of the sound textures and frequency behaviours of the feedbacked loops so this is something I am happy to share with whoever might be interested! This is definitively something I will go for another round with soon. After when listening to this I was having the image of being inside a “happy cloud” – hence the title. In a cloud drifting over landscapes, dreamlike – ((which in some some way also must be a reference to that track by 801 I liked so much when I was young))

Track originally posted for free download at soundcloud.com/miulew. More on Miulew/Eriksson at ruccas.org and miulew.blogspot.com.

September 22, 2012

Past Week at Twitter.com/Disquiet

I made one edit of significance below. The Judge Dredd quote was “4,000 frames per second” not, as I’d initially tweeted, “4,000 frames per session.”

A favorite netlabel returns after two-year absence with music from a favorite musician: http://t.co/ep7PbWr2 Kenneth Kirschner on SHSK’H. #

Dates for @djunto concerts added to “upcoming events” sidebar: Manhattan on Nov 27, San Francisco on Dec 6: http://t.co/Yh8y3liM. #

It’s nice to be able to do simple math functions in the OS X Spotlight bar. #

Guy on cellphone in quiet café talking about “break support.” People look at him and each other and smile, like, “What are you thinking?” #

An answer about what @trent_reznor‘s “Yes.” tweet was about: https://t.co/BnMcomhw New band, new EP, signed to Columbia. #

Production video from which previous tweet’s quote originated: http://t.co/HHQQAOHa #dredd #slomo #3d #

“None of us really understands what happens at 4,000 frames per second.” Very much looking forward to Dredd. #

Waiting for Tea Party to complain it isn’t video games but specifically co-op play that’s weakening America’s youth. #

Dumfounded when CCA dropped “craft” just as gen-Etsy was rising, and again that SF’s Museum of Craft & Folk must close: http://t.co/dmCvnbjB #

I hope this week’s @djunto project holds interest for folks. Employing “foley” techniques to create a “faux field recording” is enticing. #

RIP, Miss Monitor aka Tedi Thurman (b. 1923), at one time perhaps “the most recognizable female voice in the country”: http://t.co/BxoiGcBl #

This week in the @djunto we’re making a “fake field recording”: http://t.co/XdREURGZ + http://t.co/vpYbWL93 #

bouncy house music #

Baby’s first mosh pit. Hope my recording of this bouncy house comes out OK. #

Nice. Free 9-track solo 9-finger piano Nils Frahm set: http://t.co/mLJvWsMl. My interview with Frahm: http://t.co/2lCYZjwV #

My reward when I get all of this done is to (finally) read the (1979) novel on which the (1981) movie Diva was based. (Er, in translation.) #

This is the chart of the cornet’s development, which I mentioned last night @gaffta: http://t.co/ChLUAcsZ #

Extended DVD cut of Looper hinges in part on rights to Chopin Étude: http://t.co/S9T1k0T0 What year is it? Couldn’t a new recording be made? #

So, what’s going to be the “best” (for lack of a more useful term) T-Mobile Android phone in November, when my contract’s denouement begins? #

I dig my Touch & Macbook, but why my phone remains Android: widgets (notes, calendar, buttons); drag’n'drop; SD card; standard USB charging. #

10am bells pierce the collective shroud of silence in the floor of the library dedicated to “quiet study.” #

The term “indie” is at best evidence of rock’n'roll recovering from its long held delusion of its inherent exceptionalism. #

Adding “ear training” alongside “audiophile” as a word ripe for — in need of — redefinition. #

The ungainly Taylorism of “I wanna rock’n'roll all night and party every day.” So sad to think that rock’n'roll cannot itself be a party. #

The 3D effect of new iPad maps tool makes my ‘hood look like it’s built of soggy paper mache. I mean, it’s humid here, but not that humid. #

The iPad 2 updated to iOS 6. Seems faster. Do Not Disturb is nice. Free is nice. Doesn’t feel like 200 updates. Absence of widgets is silly. #

The first @trent_reznor tweet in four months is simply “Yes.” Anyone know what it’s in reference to? I am hopeful for a new film score. in reply to trent_reznor #

Great @gaffta conversation this evening: musical interfaces, virtuosity, tradition, networked participation, live coding. #

Headed to @GAFFTA for panel on alternative musical interfaces. I’m moderating, but given the panelists I’ll mostly be quiet and just marvel. #

Today’s “sound” class: Whitney Houston instrumental, Cage on Van der Rohe, Eno on perfume, ancient Greeks on how recording diminishes memory #

Key among San Francisco’s benefits: living in same city where The Conversation takes place when I’m assigning it for my class on “sound.” #

Maybe iOS 6 will be the first OS I do not early-adopt. #

Dug the Last Resort pilot OK, in part because it resuscitates the Unit part of Shawn Ryan’s work, but sure didn’t sound submerged/sub-like #

Short interview I did with Nils Frahm regarding his busted thumb, current tour, & lightly prepared piano: http://t.co/2lCYZjwV #

Guitar looks like Tom Petty’s, sounds like Brian Eno: acoustic 12-string cover of “An Ending (Ascent)”: http://t.co/WiCIaOxo #

Evening music: lovely little OP-1-recorded bit of phases, beeps, and attenuated drones by @jbutlerjbutler: http://t.co/xp43X56M #

Class I’m teaching tomorrow at Academy of Art is A Brief History of Sound: celebrity death, oral culture, anatomy, perception, synaesthesia. #

“Those places don’t exist except in the imaginations of those who sit in the editing suite.” #

Re-familiarizing myself with the Soundtracker doc about Gordon Hempton in advance of tomorrow’s sound class. #

One of those weeks when PDF-reading management on the iPad is hurting my brain. #

The 38th weekly @djunto will be an inverse take on the 37th. Details as Thursday approaches. Cc @notrobwalker @apexart #

Morning sounds: garbage truck, students chattering as they walk by house, yappy dogs, buzz of overhead plane, low-level electric whine. #

“First, the key goes in real quiet.” Watching The Conversation for the umpteenth time. Watching is the wrong word. Observing? Surveilling? #

From an Apple store to Akihabara to Macy’s: 24 (and counting) audio recordings of commercial space: http://t.co/lSzme8ob #

Have any of the USA network’s past few years of summer-season shows had a crossover? #

Deee-Lite/Thomas Dolby hits reworked in pair of commercials during one break. My memories, another’s jingle. May the circle be unbroken. #

So many pumpkins in the back of the car it looks like a Peanuts version of Invasion of the Body Snatchers. #

“It’s easy to forget how pervasive music is in retail until you go looking for place it’s not”: @notrobwalker on the current @djunto project #

Looking forward to moderating this discussion @gaffta on Wed evening, Sep 19, on “alternative musical interfaces”: http://t.co/13MzzocC #

Ghost bus. #

September 21, 2012

“Sounds of Brands / Brands of Sounds,” Week 2

Wednesday of this week was the second of the 15 weekly three-hour classes I’m teaching on sound at San Francisco’s Academy of Art (academyart.edu) this semester. Last week’s entry on the first class got a helpful and enthusiastic response, so I thought I’d do it again. As with last time, this isn’t the full lecture, and even less so is it a representation of the discussion, which this week was great; it’s just a quick run through the subjects we covered.

Per the syllabus (PDF), this second class meeting focused on “A Brief History of Sound:”

Overview: We’ll trace overlapping paths through the history of sound, beginning with the human conception of sound, and then exploring the developing role of sound in modern media.

Part I: Celebrity Death

The class starts each Wednesday at noon, and my intention was to begin this one by playing some music, specifically an instrumental version of a Whitney Houston hit. The subject at hand was “celebrity death,” more on which in a moment. The tech failed me (more likely I failed the tech), so I ended up playing the song after the class break, but in the interest of context, this is a video containing the audio:

One of the pleasures of this course is probing my own uncertainties. Last week, the specific uncertainty on which I focused related to the role of sound in the work of JJ Abrams (briefly: to what extent his notable sonic sensitivity contributes to the popularity of his projects). This week allowed me to touch on a question that haunts me: What was the emotional and cultural experience of losing a musician to death before development of recorded music?

Just ponder that for a second. It’s 1750 AD, and your favorite local opera singer or tavern troubadour has passed away unexpectedly. What does it mean that you will never again hear her or his voice? In class we discussed the way a largely oral culture might maintain the singer’s memory — there might be subsequent musicians who sing in imitation of the deceased singer, and new singers might begin their careers by emulating that singer, eventually developing their own styles. These are, of course, things that continue in our own time — there are enough Elvis impersonators and Beatles cover bands to fill Shea Stadium, and so many prominent groups originated deeply indebted melodically, and in other ways, to their forebears. We touched on various related subjects, like where theft and cultural production overlap.

I initially played the instrumental version of the Whitney Houston hit to show how our memories fill in the gap, how we can celebrate a musicians absence in this manner. I then played the opposite, a video that contains the audio of only Whitney Houston singing, minus all the instrumentation. It’s doubly affecting. First there’s the sense of loss — the performance is so emotional, it’s as if she’s mourning herself. Second there are the echoes in Houston’s singing of Michael Jackson, whose own a cappella edits circulated after his early passing (“ABC,” “I Want You Back”):

There’s a lot to discuss on this topic, and the point of these summary posts is to do just that: summarize the lecture points. So, I’ll leave that part for now.

Part 2: A (Very) Brief Timeline

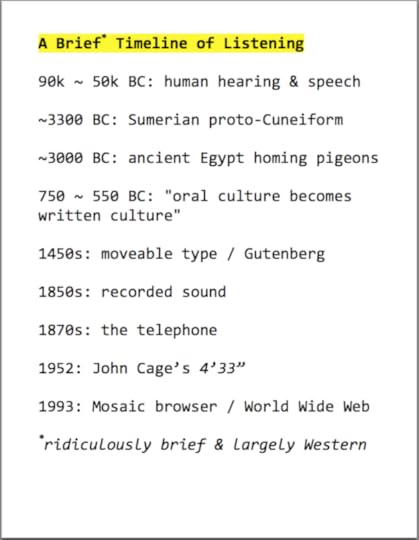

I then displayed the following timeline, and I talked through the nine points. (One thing: I am particularly uncertain about the dating of the early development of human speech ability. There are a lot of divergent takes on this timing. Fortunately for my purposes, the dating doesn’t affect the sequence, whether it’s circa 100,000 or 200,000 years ago.)

In brief, it begins with a consideration of the extent to which we were or weren’t human before we developed hearing and speech, and notes the extensive period between the origins of spoken communication and the introduction of early writing. Of all early physical technology — and I use that term so as not to exclude, for example, language, which is itself a technology — it was the homing pigeon I focused on. I was trying to emphasize an early technology that allowed people to send information faster and further than they might be able to themselves. (Later that evening, a friend suggested the bow and arrow, which considerably predates the homing pigeon, but I’m not certain that the distance a bow and arrow travels makes it as significant a development in communication distribution as the homing pigeon.)

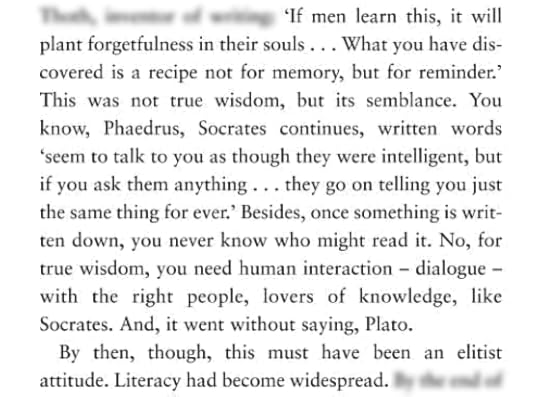

The “oral culture becomes written culture” moment was the focal point of the timeline discussion. I draw this transition primarily from the popular survey Alpha Beta: How 26 Letters Shaped the Western World (2000) by John Man, who summarizes the anxiety in ancient Greece as this transition was underway. In brief, when we gain the power to record, we begin to forget:

By the way, Man likes this quote; he also employs it in his book The Gutenberg Revolution: The Story of a Genius and an Invention That Changed the World, from 2003. Like Man, we moved from oral culture to written culture to Gutenberg and moveable type. Then we proceeded to recorded sound. (As time got closer to the present, the rapidity of innovations appeared to increase; I trust there is something of an ongoing accelerando, but there’s also the manner in which greater distance makes things appear to be coincidental.) We touched on early recordings (fun fact: the “phonautograph” of Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville was only intended for recording, not playback) and the telephone. As time marched on, I singled out John Cage’s 4’33, which just had its 60th birthday, because of its centrality to our comprehension of music in the broader context of sound — a subject that is at the core of the first three classes in this course. And we closed on the Mosaic browser, the first visual interface for the World Wide Web, which turns 20 next year. We discussed what has occurred in Mosaic’s wake — Napster, iTunes, HTML5 — but that’s just the point: those flowed from Mosaic.

Part 3: Gordon Hempton, Audio Ecologist and Soundtracker

The Cage discussion, which we returned to later in the class, led to one of the primary assignments from the previous class, which was a discussion of the documentary Soundtracker (directed by Nick Sherman), whose subject is the audio ecologist and field recorder Gordon Hempton. (The students were required to watch it before the start of class, which gave them a full week.) Hempton says at one point in the documentary, “What’s the matter with me that I could be 27 years old before I started to listen.” The goal of this class, of course, is for everyone to start listening earlier than Hempton did, even if we never achieve his level of ability. We discussed a variety of things, which I’ll summarize very briefly using the following screenshots from the film:

Hempton talks about the “American mantra,” by which he means the second-hand electrical noise pollution that is the backdrop of our lives.

This is Hempton achieving his goal, getting the sound he desired. It’s an awkward moment for viewers because his perception of his art, the act of framing sound recordings, while perfectly normal from a photographic standpoint isn’t widely comprehended from an aural one, what is often termed “phonography.” The portion of him smiling while listening to something we cannot hear makes for an excellent contrast to the famous sequence in Grizzly Man (2005), when we watch the director, Werner Herzog, listening to something he refuses to play for the sheer brutality of it.

One key reason I selected this documentary is because Hempton represents the uneasy tension between perceived “natural” and “manmade” sound, and he speaks eagerly of his time in the city, and has an interesting perspective on trains, whose sound he appreciates. While he refers to a plane as “an off-road vehicle defacing the skies,” he thinks there’s something in a train’s bearing that more comfortably makes it part of the acoustic landscape. He’s quite critical of false sounds used in place of real ones; he says of some nature recordings that use, say, a toilet to represent a mountain stream, or of recordings that selectively edit to cut out passing planes and cars: “Those places don’t exist except in the imaginations of those who sit in the editing suite.” (I also asked the students to make note of the waveform that appears on screen during these title cards. We’ll be talking about visual iconography of sound much later in the course.)

There’s a fair amount of underlying personal tension in the film, too. Why is he no longer with his family? How strongly does his hold to his depiction of people as a “noise source.” Where does his sonic attention originate?

I neglected to show the above slide in class, regrettably. It’s a fine depiction of Hempton’s talent. In the film, that circle starts large and closes in slowly on its subject. It’s an economical presentation of Hempton’s ability to locate and identify sounds.

In light of Hempton and his attention to sound, we also discussed one of the other homework assignments for the week. The first week I had them all write down memories of sounds they associate with Wednesday mornings. This week, as part of their daily sound journal entries, I asked them to write down what they heard. We discussed what was and wasn’t evident — how initial recollections might, for example, have been of loud noises, but how in turn the students found themselves paying attention this morning to quiet ones. Also, we discussed false memories, like things they thought they heard but later realized they couldn’t have actually heard.

Then we took our break.

Part 4: Listening Exercise

The class takes a 15 minute break midway through. As part of an in-class listening exercise, I asked them to take 20 minutes instead, and I instructed them to use five of those minutes to walk the four-block circumference of the school, and to pay attention to what they heard. Our class is in the Academy of Art building at 410 Bush Street, closer to Kearny than to Grant, as depicted on this Google map:

When they got back to the room after the break, I immediately paired them up and had them do a listening exercise. Each pair would walk the four-block circumference, arm in arm. For two blocks, one of them would keep their eyes closed, and then they would switch for the second two blocks. Afterwards we discussed the sense of disorientation, fear, and heightened senses that resulted — not only sound but smell, even elements of touch. They had just walked this same route by themselves, and yet with one sense removed, it was fully new. The classroom couldn’t be much better located for such an exercise. If you walk up Bush to Grant and make a right, you are at the entrance to Chinatown, a commercial block as uniquely sonorous as it is colorful (photo via wikipedia.org). (And thanks to Paolo Salvagione, of salvagione.com, for helping me think of using this exercise.)

Part 5: Three Aspects of Listening (Physiology, Synaesthesia, Perception)

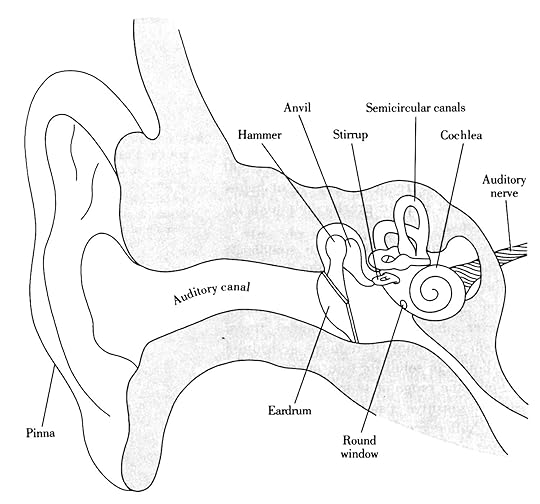

The next part of the class focused on aspects of listening. First, we went quickly over the structure of the ear, mostly to put that aside and talk about broader aspects of the listening experience, such as non-ear sensation (chest, hair follicles), and memory/experience.

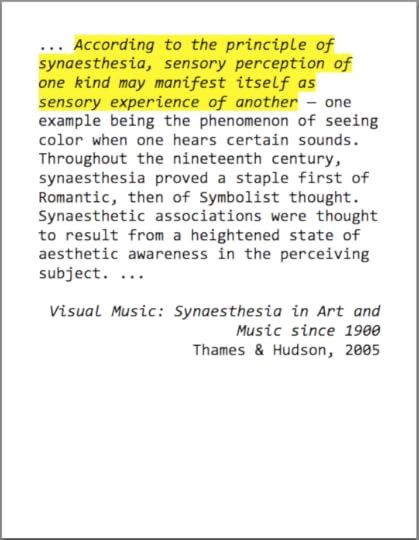

We then moved on to synaesthesia, which I often incorrectly refer to as a “confusion” of the senses, though I mean confusion in a neutral, even positive, way (along the lines of the Jimmy McHugh and Frank Loesser song “Let’s Get Lost”). We discussed the Brian Eno essay on perfume I had assigned for the class (“Scents & Sensibility,” which dates from 1992), and that led to a brief overview of ambient music in the broader context of ambient sound. For a working definition of “synaesthesia,” I employed this description (see below) from the catalog to the excellent Visual Music exhibit that showed in Los Angeles, California, and Washington, D.C., around 2005. (You’ll no doubt note the way the key quote is highlighted. I don’t trust pithy quotes, as I feel they artificially yank something out of context, so I try to display them in the context in which they first appeared, and then talk about that context a little. In explaining this presentation style to the students, I mentioned the classic example of the Stewart Brand phrase “Information wants to be free,” which for a long time was usually quoted without the sentence that originally followed it: “Information also wants to be expensive.”)

And then things came around to the final portion of the class, a discussion of “perception,” which clearly had been the thread running through the entire day’s selection of subjects, from the Greeks’ anxiety about knowledge separated from experience, to Gordon Hempton’s extraordinary ear, to the two listening exercises, and so on. The starting point for this was a selection from John Cage’s book Silence, which celebrated its 50th anniversary last year:

Part 6: Next Week’s Assignments

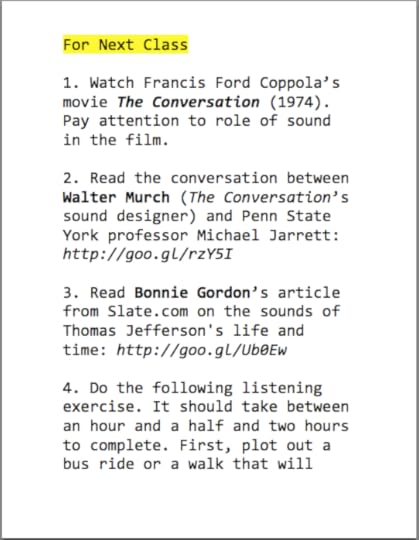

And then I went over the homework for the following week. The structure of the assignments for this course is that some reinforce what’s just been covered and some prepare for what’s about to be covered, while others bridge the gap — and every week, every day really, the students are expected to write in their sound journals. Next week is class number three, which is the final part of the first of this course’s three arcs, the one on “Listening to Media.” The class will take as its subject “The Score”:

Overview: Music and sound in film and television, its purposes, and what we can learn from its history of development.

These are the assignments due for completion by the start of the third class. The Michael Jarrett conversation with Walter Murch is at yk.psu.edu and the Bonnie Gordon piece on Thomas Jefferson is at slate.com. (Thanks to Peter Nyboer of lividinstruments.com for having reminded me about the Murch piece.)

I didn’t expect to do a second of these roundups, but the first one proved useful. Not sure if I’ll do more such posts, but we’ll see. Still 13 weeks of classes to go.

Sounds of Brands / Brands of Sounds,” Week 2

Wednesday of this week was the second of the 15 weekly three-hour classes I’m teaching on sound at San Francisco’s Academy of Art (academyart.edu) this semester. Last week’s entry on the first class got a helpful and enthusiastic response, so I thought I’d do it again. As with last time, this isn’t the full lecture, and even less so is it a representation of the discussion, which this week was great; it’s just a quick run through the subjects we covered.

Per the syllabus (PDF), this second class meeting focused on “A Brief History of Sound:”

Overview: We’ll trace overlapping paths through the history of sound, beginning with the human conception of sound, and then exploring the developing role of sound in modern media.

Part I: Celebrity Death

The class starts each Wednesday at noon, and my intention was to begin this one by playing some music, specifically an instrumental version of a Whitney Houston hit. The subject at hand was “celebrity death,” more on which in a moment. The tech failed me (more likely I failed the tech), so I ended up playing the song after the class break, but in the interest of context, this is a video containing the audio:

One of the pleasures of this course is probing my own uncertainties. Last week, the specific uncertainty on which I focused related to the role of sound in the work of JJ Abrams (briefly: to what extent his notable sonic sensitivity contributes to the popularity of his projects). This week allowed me to touch on a question that haunts me: What was the emotional and cultural experience of losing a musician to death before development of recorded music?

Just ponder that for a second. It’s 1750 AD, and your favorite local opera singer or tavern troubadour has passed away unexpectedly. What does it mean that you will never again hear her or his voice? In class we discussed the way a largely oral culture might maintain the singer’s memory — there might be subsequent musicians who sing in imitation of the deceased singer, and new singers might begin their careers by emulating that singer, eventually developing their own styles. These are, of course, things that continue in our own time — there are enough Elvis impersonators and Beatles cover bands to fill Shea Stadium, and so many prominent groups originated deeply indebted melodically, and in other ways, to their forebears. We touched on various related subjects, like where theft and cultural production overlap.

I initially played the instrumental version of the Whitney Houston hit to show how our memories fill in the gap, how we can celebrate a musicians absence in this manner. I then played the opposite, a video that contains the audio of only Whitney Houston singing, minus all the instrumentation. It’s doubly affecting. First there’s the sense of loss — the performance is so emotional, it’s as if she’s mourning herself. Second there are the echoes in Houston’s singing of Michael Jackson, whose own a cappella edits circulated after his early passing (“ABC,” “I Want You Back”):

There’s a lot to discuss on this topic, and the point of these summary posts is to do just that: summarize the lecture points. So, I’ll leave that part for now.

Part 2: A (Very) Brief Timeline

I then displayed the following timeline, and I talked through the nine points. (One thing: I am particularly uncertain about the dating of the early development of human speech ability. There are a lot of divergent takes on this timing. Fortunately for my purposes, the dating doesn’t affect the sequence, whether it’s circa 100,000 or 200,000 years ago.)

In brief, it begins with a consideration of the extent to which we were or weren’t human before we developed hearing and speech, and notes the extensive period between the origins of spoken communication and the introduction of early writing. Of all early physical technology — and I use that term so as not to exclude, for example, language, which is itself a technology — it was the homing pigeon I focused on. I was trying to emphasize an early technology that allowed people to send information faster and further than they might be able to themselves. (Later that evening, a friend suggested the bow and arrow, which considerably predates the homing pigeon, but I’m not certain that the distance a bow and arrow travels makes it as significant a development in communication distribution as the homing pigeon.)

The “oral culture becomes written culture” moment was the focal point of the timeline discussion. I draw this transition primarily from the popular survey Alpha Beta: How 26 Letters Shaped the Western World (2000) by John Man, who summarizes the anxiety in ancient Greece as this transition was underway. In brief, when we gain the power to record, we begin to forget:

By the way, Man likes this quote; he also employs it in his book The Gutenberg Revolution: The Story of a Genius and an Invention That Changed the World, from 2003. Like Man, we moved from oral culture to written culture to Gutenberg and moveable type. Then we proceeded to recorded sound. (As time got closer to the present, the rapidity of innovations appeared to increase; I trust there is something of an ongoing accelerando, but there’s also the manner in which greater distance makes things appear to be coincidental.) We touched on early recordings (fun fact: the “phonautograph” of Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville was only intended for recording, not playback) and the telephone. As time marched on, I singled out John Cage’s 4’33, which just had its 60th birthday, because of its centrality to our comprehension of music in the broader context of sound — a subject that is at the core of the first three classes in this course. And we closed on the Mosaic browser, the first visual interface for the World Wide Web, which turns 20 next year. We discussed what has occurred in Mosaic’s wake — Napster, iTunes, HTML5 — but that’s just the point: those flowed from Mosaic.

Part 3: Gordon Hempton, Audio Ecologist and Soundtracker

The Cage discussion, which we returned to later in the class, led to one of the primary assignments from the previous class, which was a discussion of the documentary Soundtracker (directed by Nick Sherman), whose subject is the audio ecologist and field recorder Gordon Hempton. (The students were required to watch it before the start of class, which gave them a full week.) Hempton says at one point in the documentary, “What’s the matter with me that I could be 27 years old before I started to listen.” The goal of this class, of course, is for everyone to start listening earlier than Hempton did, even if we never achieve his level of ability. We discussed a variety of things, which I’ll summarize very briefly using the following screenshots from the film:

Hempton talks about the “American mantra,” by which he means the second-hand electrical noise pollution that is the backdrop of our lives.

This is Hempton achieving his goal, getting the sound he desired. It’s an awkward moment for viewers because his perception of his art, the act of framing sound recordings, while perfectly normal from a photographic standpoint isn’t widely comprehended from an aural one, what is often termed “phonography.” The portion of him smiling while listening to something we cannot hear makes for an excellent contrast to the famous sequence in Grizzly Man (2005), when we watch the director, Werner Herzog, listening to something he refuses to play for the sheer brutality of it.

One key reason I selected this documentary is because Hempton represents the uneasy tension between perceived “natural” and “manmade” sound, and he speaks eagerly of his time in the city, and has an interesting perspective on trains, whose sound he appreciates. While he refers to a plane as “an off-road vehicle defacing the skies,” he thinks there’s something in a train’s bearing that more comfortably makes it part of the acoustic landscape. He’s quite critical of false sounds used in place of real ones; he says of some nature recordings that use, say, a toilet to represent a mountain stream, or of recordings that selectively edit to cut out passing planes and cars: “Those places don’t exist except in the imaginations of those who sit in the editing suite.” (I also asked the students to make note of the waveform that appears on screen during these title cards. We’ll be talking about visual iconography of sound much later in the course.)

There’s a fair amount of underlying personal tension in the film, too. Why is he no longer with his family? How strongly does his hold to his depiction of people as a “noise source.” Where does his sonic attention originate?

I neglected to show the above slide in class, regrettably. It’s a fine depiction of Hempton’s talent. In the film, that circle starts large and closes in slowly on its subject. It’s an economical presentation of Hempton’s ability to locate and identify sounds.

In light of Hempton and his attention to sound, we also discussed one of the other homework assignments for the week. The first week I had them all write down memories of sounds they associate with Wednesday mornings. This week, as part of their daily sound journal entries, I asked them to write down what they heard. We discussed what was and wasn’t evident — how initial recollections might, for example, have been of loud noises, but how in turn the students found themselves paying attention this morning to quiet ones. Also, we discussed false memories, like things they thought they heard but later realized they couldn’t have actually heard.

Then we took our break.

Part 4: Listening Exercise

The class takes a 15 minute break midway through. As part of an in-class listening exercise, I asked them to take 20 minutes instead, and I instructed them to use five of those minutes to walk the four-block circumference of the school, and to pay attention to what they heard. Our class is in the Academy of Art building at 410 Bush Street, closer to Kearny than to Grant, as depicted on this Google map:

When they got back to the room after the break, I immediately paired them up and had them do a listening exercise. Each pair would walk the four-block circumference, arm in arm. For two blocks, one of them would keep their eyes closed, and then they would switch for the second two blocks. Afterwards we discussed the sense of disorientation, fear, and heightened senses that resulted — not only sound but smell, even elements of touch. They had just walked this same route by themselves, and yet with one sense removed, it was fully new. The classroom couldn’t be much better located for such an exercise. If you walk up Bush to Grant and make a right, you are at the entrance to Chinatown, a commercial block as uniquely sonorous as it is colorful (photo via wikipedia.org). (And thanks to Paolo Salvagione, of salvagione.com, for helping me think of using this exercise.)

Part 5: Three Aspects of Listening (Physiology, Synaesthesia, Perception)

The next part of the class focused on aspects of listening. First, we went quickly over the structure of the ear, mostly to put that aside and talk about broader aspects of the listening experience, such as non-ear sensation (chest, hair follicles), and memory/experience.

We then moved on to synaesthesia, which I often incorrectly refer to as a “confusion” of the senses, though I mean confusion in a neutral, even positive, way (along the lines of the Jimmy McHugh and Frank Loesser song “Let’s Get Lost”). We discussed the Brian Eno essay on perfume I had assigned for the class (“Scents & Sensibility,” which dates from 1992), and that led to a brief overview of ambient music in the broader context of ambient sound. For a working definition of “synaesthesia,” I employed this description (see below) from the catalog to the excellent Visual Music exhibit that showed in Los Angeles, California, and Washington, D.C., around 2005. (You’ll no doubt note the way the key quote is highlighted. I don’t trust pithy quotes, as I feel they artificially yank something out of context, so I try to display them in the context in which they first appeared, and then talk about that context a little. In explaining this presentation style to the students, I mentioned the classic example of the Stewart Brand phrase “Information wants to be free,” which for a long time was usually quoted without the sentence that originally followed it: “Information also wants to be expensive.”)

And then things came around to the final portion of the class, a discussion of “perception,” which clearly had been the thread running through the entire day’s selection of subjects, from the Greeks’ anxiety about knowledge separated from experience, to Gordon Hempton’s extraordinary ear, to the two listening exercises, and so on. The starting point for this was a selection from John Cage’s book Silence, which celebrated its 50th anniversary last year:

Part 6: Next Week’s Assignments

And then I went over the homework for the following week. The structure of the assignments for this course is that some reinforce what’s just been covered and some prepare for what’s about to be covered, while others bridge the gap — and every week, every day really, the students are expected to write in their sound journals. Next week is class number three, which is the final part of the first of this course’s three arcs, the one on “Listening to Media.” The class will take as its subject “The Score”:

Overview: Music and sound in film and television, its purposes, and what we can learn from its history of development.

These are the assignments due for completion by the start of the third class. The Michael Jarrett conversation with Walter Murch is at yk.psu.edu and the Bonnie Gordon piece on Thomas Jefferson is at slate.com. (Thanks to Peter Nyboer of lividinstruments.com for having reminded me about the Murch piece.)

I didn’t expect to do a second of these roundups, but the first one proved useful. Not sure if I’ll do more such posts, but we’ll see. Still 13 weeks of classes to go.

The Prepared Hand (MP3s)

Nils Frahm, the German pianist, is currently on tour. Yesterday he turned 30, and to celebrate he gave a present to his fans: a collection of nine short pieces for free download. Why nine? Because he was playing with nine fingers. Why nine fingers? Because one of them is out of commission. Frahm busted a thumb while bracing himself during a fall, and has several screws — a handful, one might say — to show for it. That’s his thumb up above in the X-ray. The image initially accompanied a single track he’d uploaded to SoundCloud, “Song for 9 Fingers.” The full EP, titled Screws, is highly recommended. It is Frahm at his most intimate. The texture of his instrument, the sound of the piano’s mechanisms, the fundamental physical interactions of his body and the machine, are almost as important to the recorded sound as are the Satie-eqsue melodies he pursues. Key among these melodies is “Me,” which of all nine tracks is the one in which background noises come closest to gaining parity with the foreground music, combining into a rich sonic spaciousness. The attention to detail evidences why the word “dust” carries such meaning for turntablists, beat makers, and crate diggers, and it’s a strong cross-cultural experience to hear those textures embraced by a pianist. There’s an aura of antiquity to what Frahm is up to, a fragility that can be mesmerizing.

I interviewed Frahm recently for the Colorado Springs Independent (“Felt Up”), and talked with him about how his live performances differ from his recorded output, his use of felt in preparing his piano, his favorite John Cage work (“Imaginary Landscape”), and his relationship with the various pianos he encounters on tour. “They have 88 times of the same mechanism,” he said, “and usually one or three aren’t working. I tweak little things, modify slightly. Otherwise, you deal with the character of it, and get in a dialog with a specific instrument.”

Screws EP originally posted for free download, as a Zip archive of MP3s or AIF files, at soundcloud.com/erasedtapes, which also houses “Song for 9 Fingers.” More on Frahm at nilsfrahm.de. Read the interview at csindy.com. Tour dates at erasedtapes.com, his label.

September 20, 2012

Disquiet Junto Project 0038: Zola’s Foley

Each Thursday evening at the Disquiet Junto group on Soundcloud.com a new compositional challenge is set before the group’s members, who then have just over four days to upload a track in response to the assignment. Membership to the Junto is open: just join and participate.

The assignment was made early in the afternoon, California time, on Thursday, September 13, with 11:59pm on the following Monday, September 17, as the deadline. View a search return for all the entries as they are posted: disquiet0037-asrealasitgets1. (There are no translations this week.)

These are the instructions that went out to the group’s email list (at tinyletter.com/disquiet-junto). The project is one in a foreseen series being done in conjunction with the exhibit As Real As It Gets, organized by Rob Walker. The exhibit will run at the gallery Apex Art in Manhattan from November 15 – December 22, 2012. More information on the exhibit at apexart.org. The list of featured participants in the exhibit is: Kelli Anderson, Conrad Bakker, Beach Packaging Design, Matt Brown, Steven M. Johnson, Last Exit To Nowhere, MakerBot Industries, The Marianas (Michael Arcega and Stephanie Syjuco), Angie Moramarco, Oliver Munday, Omni Consumer Products, Staple Design, U.S. Government Accountability Office, Ryan Watkins-Hughes, Marc Weidenbaum/Disquiet Junto, Shawn Wolfe, and Dana Wyse.

Disquiet Junto Project 0038: Zola’s Foley

This project is a follow-up to last week’s. Last week, for the 37th project, we focused on pure, unadulterated field recording; the project was to “record sound from a large retail space, preferably a department store.”

This week, for the 38th project, we will create an “artificial field recording.” That is, this week we’ll make something that to the listener appears to be a field recording, but is in truth entirely constructed. The aim carries over from last week: the finished audio should appear to be that of a large department store.

Background: The goal for this project is twofold. In the immediate sense, it is to explore foley techniques from film and television sound, in which noises are employed to suggest other sounds (i.e., a bicycle bell suggests a cash register, layered and echoed footsteps suggest a crowd, a doorbell suggests an elevator).

The project, however, has broader intentions. It’s being undertaken in association with the exhibit As Real as It Gets, organized by Rob Walker. The exhibit draws from Émile Zola’s novel Au Bonheur des Dames (The Ladies’ Paradise), published in 1883, which depicts life and commerce in a massive department store in Paris. As Real as It Gets will run at the gallery Apex Art in Manhattan from November 15 – December 22, 2012. Sounds produced for this Disquiet Junto project will be considered to be played in the gallery as part of the exhibit, and will also be made available to Disquiet Junto participants and other musicians and sound artists for subsequent projects related to Walker’s exhibit.

There are also plans for a Disquiet Junto concert at Apex Art on Tuesday, November 27, in conjunction with the exhibit.

This is Apex’s initial, brief description of the upcoming exhibit: “As Real as It Gets gathers fictional products, imaginary brands, hypothetical advertising and speculative objects, devised by artists, designers, and companies. We resist commercial material culture as inauthentic, phony, and less than legitimate, but should we? Presenting the marketplace as medium — while supplies last.”

Walker is a contributing writer to The New York Times Magazine and Design Observer, and the author of Buying In: The Secret Dialogue Between What We Buy and Who We Are (Random House: 2008) and Letters from New Orleans (Garrett County Press: 2005). Walker co-founded, with Joshua Glenn, the Significant Objects project.

Deadline: Monday, September 24, at 11:59pm wherever you are.

Length: Your finished work should be between 1 and 4 minutes in length.

Information: Please when posting your track on SoundCloud, include a description of your process in planning, composing, and recording it. This description is an essential element of the communicative process inherent in the Disquiet Junto.

Title/Tag: When adding your track to the Disquiet Junto group on Soundcloud.com, please include the term “disquiet0038-asrealasitgets2” in the title of your track, and as a tag for your track.

Download: For this project, your track should be set as downloadable, and allow for attributed remixing (i.e., a Creative Commons License permitting non-commercial sharing with attribution).

Linking: When posting the track, be sure to include this information:

This Disquiet Junto project was done in association with the exhibit As Real As It Gets, organized by Rob Walker at the gallery Apex Art in Manhattan (November 15 – December 22, 2012):

http://apexart.org/exhibitions/walker...

More on this 37th Disquiet Junto project at:

http://disquiet.com/2012/09/20/disqui...

More details on the Disquiet Junto at:

Photo of Émile Zola via wikipedia.org.

September 18, 2012

The Lathe of Brooklyn (MP3)

The great Touch Radio podcast has uploaded audio from just a few days ago. The concert in question was a show at Our Lady of Lebanon Cathedral in Brooklyn Heights, New York. Eleh was the headliner, and the opener was Lary 7 (pictured above in a photo of the event from Touch). Charactertistic for the Touch Radio series, there’s close to no information about the event provided. What there is is half an hour of increasingly violent chafing, noises of mechanisms in action, echoed in a reverberant space. Fortunately, a lengthy New York Times review of the Eleh show allowed a parenthetical reference to Lary 7′s opening set: “The opening act was Lary 7, a New York artist who used a lathe-cutter onstage to record the hum and buzz of the machine itself onto a black disc; and then played back the recording with a tonearm. It was process-oriented, less spiritual and much less attractive as sound.” Irritation, it appears, is in the ear of the beholder (MP3).

Download audio file (Radio83.mp3)

The concert was one in a series of events celebrating Touch’s 30th anniversary. Advance word of the show was at issueprojectroom.org. Recording originally posted for free download at touchradio.org.uk. More on Touch’s 30th anniversary at 30.touchmusic.org.uk. Here’s to hoping that the Eleh part of the evening gets a post-concert opportunity for an audience.

September 17, 2012

Two at a Drone (MP3)

There’s no immediate telling if at the 2:26-minute point along the 10:57-long timeline of “C Drone,” when the higher-pitched, more sinuous drone emerges from a thicker, more burr-like drone, one of those in particular can be attributed to He Can Jog (aka Erik Schoster) and the other to Nomad Palace (aka Nate Zabriskie). It’s a duet, a collaboration, per the track’s title (Schoster inserts a “with Nomad Palace” parenthetical after the “C Drone”), but beyond that, little is made clear. Both musicians live in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and are two thirds of the band Cedar AV (the missing piece being Nicholas Sanborn). They have plenty of collaborative performance experience between them, and thus the apparent parts within “C Drone” could just as likely be the result of their mutual efforts, not simply an expression of their simultaneous performance. Either way, it’s a strong piece. Schoster in his brief note calls it a “drone /not-drone,” which is apt — it’s more of a series of drones, from oh-so-quiet, to richly patterned, to a cicada frenzy, sewn into something that progress like a piece of program music.

Track originally posted for free download at soundcloud.com/hecanjog. More on Schoster at hecanjog.com. More on Zabriskie at nomadpalace.net. More on Cedar AV at cedarav.org.