Marc Weidenbaum's Blog, page 452

July 3, 2013

Mälzel’s Metronome 3/3: The Metronome Countdown / Der Metronome Countdown

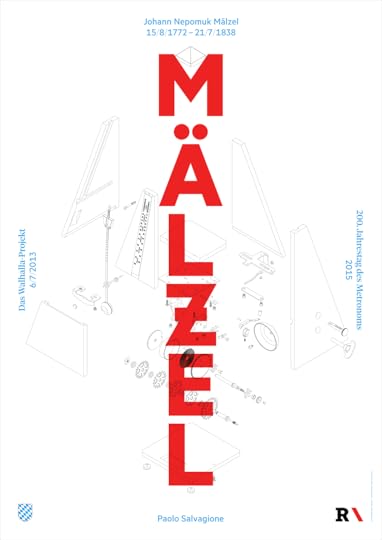

This Saturday, July 6, a series of works by artist Paolo Salvagione will debut in Regensburg, Germany, and at the nearby Walhalla. They all revolve around the life and work of Johann Nepomuk Mälzel (1772-1838), best known as having perfected the analog metronome as we know it. As part of my continuing work with Salvagione, I wrote three essays about the Regensburg/Walhalla/Mälzel project. The first, posted two days ago, was “Time Changes Everything” / “Zeit verändert alles.” The second, posted yesterday, was “Eternal Partners” / “Ewige Partner.” This is the third of them:

The Metronome Countdown

The year 2015 will mark the 200th anniversary of the introduction of a device that set the pace for all music that followed. The device is the metronome, which in 1815 was perfected by a roguish tinkerer named Johann Nepomuk Mälzel, who was born in Regensburg, Germany, 43 years prior. That would be 1772, the same year as romantic poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, utopian philosopher Charles Fourier, and rocket artillery pioneer Sir William Congreve. If both technology and the arts experienced revolutions during this era, the metronome’s pendulum teetered at their fulcrum.

The influence of Mälzel’s metronome cannot be overstated. Long before the Internet set the digital clip for contemporary life; long before turntables were equipped with buttons marked 33, 45, and 78; long before the atomic clock employed electromagnetism to dictate the highest standard for timekeeping, the humble metronome employed mechanical means to give shape to time, and to make those shapes consistent, communicable, universal.

In his lifetime, Mälzel’s most advanced early adopter was none other than the composer Ludwig van Beethoven, who was two years Mälzel’s senior. Beethoven was early on intrigued by Mälzel’s contraption, and late in life, long after he had lost his hearing, he went back to his earlier symphonies and notated what he deemed the “correct” timings. That these metronomically precise timings were considerably quicker than considered appropriate to musicians at the time (and to this day) remains something of a musicological mystery.

As for Mälzel, he remains as ubiquitous as his device, yet his presence is so prevalent as to be nearly invisible, rendered as a mere pair of initials: the “MM” notation that in traditional musical scores states the pace of a work. (The double M stands for “Mälzel’s Metronome.”) His device is music’s training wheels, its click track. It is the beat that percusses through rehearsal halls and yet is — with some notable exceptions, such as György Ligeti’s 1962 “Poème Symphonique,” composed for 100 metronomes — mute by the time the curtain rises.

The goal of the celebration this year in Mälzel’s hometown, as the two-century anniversary of his invention comes into view, is to build public support for his wider recognition — to bring Mälzel’s mechanical triumph to the foreground.

And this is the German translation:

Der Metronome Countdown

Das Jahr 2015 markiert den 200. Jahrestag der Perfektionierung eines Gerätes, das das Tempo für jede Musik festlegte, die nach dessen Erfindung komponiert wurde: Das Metronom.

Dietrich Nikolaus Winkel reklamiert die Erfindung des Musik-Chronometers für sich, aber verfeinert und schließlich vollendet wurde das Metronom 1815 von einem schelmischen Bastler namens Johann Nepomuk Mälzel, der 43 Jahre früher in Regensburg zur Welt kam. Es handelt sich um das Jahr 1772, in dem unter anderem der romantische Dichter Samuel Taylor Coleridge, der utopische Philosoph Charles Fourier und Raketenartillerie Pionier Sir William Congreve ebenfalls das Licht der Welt erblickten. Wenn man die Revolutionen in den Bereichen Technik und Kunst dieser Zeit betrachtet, dann symbolisiert das Metronom mit seinem Pendel genau diesen Dreh- und Angelpunkt.

Der Einfluss von Mälzels Metronom kann nicht hoch genug bewertet werden. Lange bevor der digitale Clip das zeitgenössische Leben prägte, lange bevor sich auf Plattenspielern die Umdrehungen 78, 45 und 33 einstellen ließen, lange bevor die Atomuhr mit Hilfe von Elektromagnetismus den höchsten Standard der Zeitmessung diktierte, verwendete das bescheidene Metronom mechanische Mittel, um der Zeit eine Form zu geben und diese Form konsistent, übertragbar und universal zu machen.

Der erste moderne Anwender von Mälzels Erfindung war kein geringerer als Ludwig van Beethoven, der nur zwei Jahre älter war als Mälzel selbst. Von Anfang an war Beethoven von Mälzels komischem Apparat fasziniert. Gegen Ende seines Lebens, als er schon lange seinen Gehörsinn verloren hatte, kehrte Beethoven zu seinen ersten Symphonien zurück und notierte diese neu in der jetzt “richtigen” zeitlichen Festlegung. Diese neuen präzisen metronomischen Anweisungen waren deutlich schneller und wurden von den damaligen Musikern (zum Teil auch jetzt noch) als unangemessen angesehen und bleiben bis heute ein musikwissenschaftliches Rätsel.

Mälzel ist zwar als Person allgegenwärtig wie sein Gerät, jedoch macht dessen weite Verbreitung ihn gleichzeitig auch fast unsichtbar. In Erscheinung tritt er lediglich durch seine Initialen “MM”, die in traditionellen Partituren das Tempo des Werkes angeben. (Das Doppel M steht für Mälzels Metronom). Mälzels Gerät ist das Rückgrat der Musik, die Click-Spur. Es ist der Beat, der durch die Proben schwingt und verstummt, sobald sich der Vorhang hebt. Mit einer bemerkenswerten Ausnahme, dem „Poème Symphonique“ von György Ligeti, einer Komposition für 100 Metronome, aus dem Jahre 1962.

Mit unserer Kampagne wollen wir im Rahmen dieser einmaligen Veranstaltung auf der Walhalla die Gelegenheit ergreifen, Mälzel in seiner Geburtsstadt zu feiern und das 2015 anstehende 200-jährige Jubiläum seiner Erfindung einer größeren Öffentlichkeit bekannt zu machen. Wir werben für eine breitere Anerkennung seiner Leistung und rücken Mälzels mechanischen Triumph in den Vordergrund.

More information at salvagione.com. Design by boondesign.com. German translation (from English) by Simone Junge. Initial project announcement: disquiet.com, theater-regensburg.de.

July 2, 2013

Squeak and Whorl

With a rhythm like a squeegee at its first rave, a foundation drone like the HVAC has been occupied by a poltergeist, and such an extended playing time that the repetition veers toward the hallucinogenic, the single-track Sprites. 1 release by Jjoth is an exercise in low-bit rumble. A desiccated maelstrom, it trudges thoughtfully through nearly eight minutes of squeak and whorl. If there were a Rosencrantz and Guildenstern video game, this would be its score (MP3).

Download audio file (jjoth%20-%20sprites.%201.mp3)

Track available for free download at archive.org as part of the 8ravens.blogspot.com netlabel.

Mälzel’s Metronome 2/3: Eternal Partners / Ewige Partner

This Saturday, July 6, a series of works by artist Paolo Salvagione will debut in Regensburg, Germany, and at the nearby Walhalla. They all revolve around the life and work of Johann Nepomuk Mälzel (1772-1838), best known as having perfected the analog metronome as we know it. As part of my continuing work with Salvagione, I wrote three essays about the Regensburg/Walhalla/Mälzel project. The first, posted yesterday, was “Time Changes Everything” / “Zeit verändert alles.” This is the second of them:

Eternal Partners

Albert Einstein is there. Beethoven, too. Bach. Mendel. Copernicus. All manner of scientists and artists, clergy and warriors. There are those synonymous with their inventions, such as movable type’s Johannes Gutenberg, and those whose work has long since surpassed them, such Peter Henlein, who made time portable, in the form of the watch. One wonders if Henlein feels out of place in a hall of immortals, those beyond time.

The hall is the Walhalla, the memorial to Germanic accomplishment. Modeled on the Parthenon, it sits near Regensburg, Germany, overlooking the Danube. No, Johann Strauss II did not make the cut, though other Austrians did, including three composers, two dukes, and a duchess. Richard Strauss, no relation, is present, as is Richard Wagner, the gods of whose Ring Cycle make their home in another Walhalla.

They are here in the form of busts and plaques. Beethoven’s bust is an immovable force of wild hair and wilder eyes. It is marked

“tondichter” — a splendid German concatenation, its melding (tone + writer) preferable to its subject over the standard “komponist.”

Einstein’s bust is adorned with a bow tie, his hair here far better kempt than his trademark unruly nest, the exuberant tangle that seemed like a projection of his gifted brain. His signature is affixed at the upward angle of a robust ego. His face here is oddly symmetrical; the modern sculpting could be a prototype for a posthumous effort in commercial branding.

The commercial comparison is worth exploring. Like choice items in an elegant boutique, the heroes of the Walhalla are presented devoid of context — much as they are devoid of a torso, let alone limbs. When one succumbs to the temptation to purchase an item from a certain type of shop, one takes it home only to be reminded just how many other objects one already possesses. One has purchased the object, but sadly not the space in which it was displayed. Perhaps the strongest critique of genius is the extent to which, over time, individuals gain credit for not only the giants on whose shoulders they stood, but the contemporary communities in which they lived and worked. When one buys into the idea of genius, one loses sight of the context in which genius flourishes.

This exhibit is intended to probe, if not right, two such wrongs.

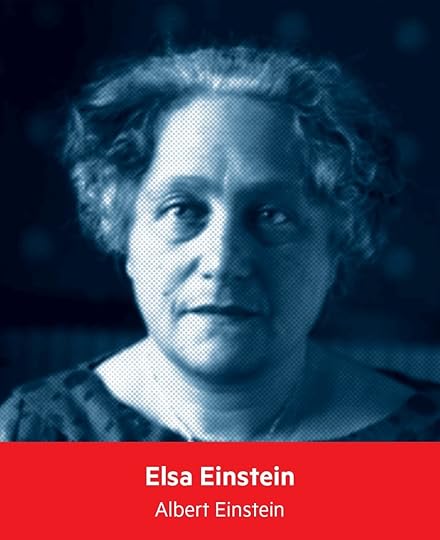

First is to acknowledge the life partners who shared their households with those who have been subsequently severed from them. For a select number of these individuals, placards have been placed temporarily to remind us of a wife, of a husband, of a mistress — and in the case of the occasional nun, of their betrothed, the truly eternal partner.

Second is to take the measurement of the hall where, it has been proposed, the inventor of the metronome, Regensburg native Johann Nepomuk Mälzel, should be installed. Should not the metronome’s inventor have the opportunity to engage in eternal debate with Einstein, who, in his theory of relativity, famously rebutted the existence of a “universally audible tick-tock”?

And this is the German translation:

Ewige Partner

Albert Einstein ist da. Ebenso Beethoven, Bach, Mendel und Kopernikus. Alle Arten von Wissenschaftlern, Künstlern, Geistlichen und Kriegern sind hier versammelt. Es gibt diejenigen, die gleichbedeutend sind mit ihren Erfindungen, wie beispielsweise Johannes Gutenberg und andere, deren Beitrag durch den Lauf der Zeit längst übertroffen wurde, wie Peter Henlein z.B., der mit seiner Erfindung einer tragbaren Uhr die Zeit transportabel machte. Man könnte sich fragen, ob Henlein sich vielleicht deplatziert vorkommt in einer Halle von Unsterblichen, unter all denen, die jenseits der Zeit weiterleben.

Diese Halle ist die Walhalla, das Denkmal für deutsche Geistesgrößen. Entworfen nach dem Modell des Parthenon befindet sich das Monument unweit von Regensburg auf dem Bräuberg, mit Blick über die Donau. Nein, Johann Strauss II ist nicht in die Auswahl gekommen, während andere Österreicher, u.a. drei Komponisten, zwei Herzöge und eine Herzogin Einlass fanden. Richard Strauss, nicht verwandt mit Johann, ist ebenso anwesend wie Richard Wagner, dessen Götter im Ring des Nibelungen in einem anderen Walhalla ihr Zuhause finden.

Sie alle sind hier in Form von Büsten oder Gedenktafeln. Eine unerschütterliche Kraft spricht aus Beethovens Büste mit wildem Haar und noch wilderen Augen. Die Büste ist beschriftet mit „Tondichter“ anstelle von „Komponist.“

Einsteins Büste ist mit einer Fliege geschmückt. Seine Frisur erscheint viel ordentlicher als das übliche wilde Nest von Haar, seinem Markenzeichen. Dieses übersprudelnde Durcheinander, das sofort das Genie seiner Geisteskraft suggeriert. Seine Unterschrift ist in einem nach oben gerichteten Winkel angebracht, Ausdruck eines kräftigen Egos. Sein Gesicht ist merkwürdig symmetrisch. Die moderne Büste erinnert an einen Prototyp für kommerzielle Massenherstellung.

Der Vergleich mit einer Ware ist der näheren Betrachtung wert. Wie Artikel in einer eleganten Boutique sind die Helden in der Walhalla nicht nur ohne Körper und Arme repräsentiert, sonderen auch ohne jeden weiteren Zusammenhang. Wie oft erliegen wir der Versuchung, in irgendeinem Geschäft einen Gegenstand zu erwerben, nur um dann zuhause festzustellen, wie viele Dinge wir schon besitzen. Zwar hat man das begehrte Objekt erstanden, aber leider nicht den Zusammenhang, in dem es feilgeboten wurde. Wahrscheinlich liegt die stärkste Kritik am Genie darin, dass ein Individuum Anerkennung für eine Leistung erlangt, die nicht nur auf den großen Schultern seiner Vorgänger ruht, sondern auch abhängig ist von der Zeit und der Gesellschaft, in der es wirkte und lebte. Wenn man an der Idee des Genies festhält, verliert man leicht den Blick dafür, in welchem Zusammenhang dieses Genie zur Blüte kam.

Die Ausstellung in der Ruhmeshalle bietet jedenfalls Anlass, die Frage des Zusammenhangs zu erforschen, auch ohne unbedingt gleich alles richtigzustellen.

Wir wollen zuerst einmal die Lebenspartner anerkennen, die das Alltagsleben der Geistesgrößen begleiteten und teilten. Für eine ausgewählte Anzahl von Individuen werden vorübergehend Gedenktafeln an die Ehefrau, den Ehemann oder die Geliebte aufgestellt. Im Falle der vereinzelten Ordensfrau mag es eine Gedenktafel für den himmlischen Bräutigam geben, dem sie sich versprochen hat, dem wahrhaft ewigen Partner.

Des weiteren wird vorgeschlagen, auszumessen, an welcher Stelle der Halle der Vollender des Metronoms, Johann Nepomuk Mälzel,

gebürtiger Regensburger, installiert werden soll. (Ja, „Vollender” statt der selbsttäuschenden Fiktion des „Genies”, welches Ähnlichkeit hat mit der selbst täuschenden Fiktion des „Erfinders”!) Sollte nicht der führende Entwickler des Metronoms die Gelegenheit zu einer ewigen Debatte mit Einstein haben, der in seiner Relativitätstheorie die Existenz eines „universell hörbaren Tick-Tack” widerlegte?

More information at salvagione.com. Design by boondesign.com. German translation (from English) by Simone Junge. Initial project announcement: disquiet.com, theater-regensburg.de.

July 1, 2013

Mälzel’s Metronome 1/3: Time Changes Everything / Zeit Verändert Alles

This Saturday, July 6, a series of works by artist Paolo Salvagione will debut in Regensburg, Germany, and at the nearby Walhalla. They all revolve around the life and work of Johann Nepomuk Mälzel (1772-1838), best known as having perfected the analog metronome as we know it. As part of my continuing work with Salvagione, I wrote three essays about the Regensburg/Walhalla/Mälzel project. This is the first of them:

Time Changes Everything

Tick. Tick. Tick. The tick is, perhaps, the smallest self-contained sound. Certainly the tick lacks the vaporous quality of a low-level drone, the drone being the de facto sonic stand-in for haze, for background, for apparition. The tick has dimension. Yet, for sheer pixel-width, pixel-height, pixel-depth stature, the tick is a sound incapable of overshadowing anything else.

Now, the tick does seem to fall short in one particular dimension, the fourth: time. So brief is the tick that it suggests itself to have ended at the exact same moment it began. This is why the tick is essential in the counting of time, because it can participate in the measurement of time without bringing along its own temporal baggage. Time, we know, changes everything.

Time changes everything, including how music about time is perceived. In 1965, a work by the Hungary-based composer György Ligeti was performed in Manhattan for the first time. Composed three years earlier, his “Poème Symphonique” was written for an ensemble whose dimensions were on the order of a symphony orchestra’s: 100 strong. However, in the case of Ligeti’s “Poème,” each part is played by the exact same instrument: a metronome.

The metronome is a device intended for the keeping of time by musicians, not the production of music itself. The result is a low-level cacophony whose makeup varies, as might any composition, by setting. There are numerous performances on YouTube, some with the feel of a clock-maker’s workshop after hours, others more akin to a feral nest of cicadas. In 1965, when the “Poème” had its Manhattan debut, the critic in the New York Times described it as an appetizer; the brief review closed with no enthusiasm: “That’s all there was to it, 100 clicking metronomes winding down.” A decade and a half later, the same paper, in a brief summary of Ligeti’s career, explained that he had been “acclaimed in the 1960s

for ‘Poème Symphonique,’” the very same work. Nearly 20 years after that initial review, the work was singled out by the Times as evidence of the composer’s “stealthy genius”: “it seems an elaborate prank at first, then turns strangely mesmerizing.”

To be clear, Ligeti is not alone in having taken the service tool for musicians and turned it into an instrument. He wasn’t even the first; Japanese composer Toshi Ichiyanagi, born a decade after Ligeti, has his own “Music for Electric Metronomes” work, dating from 1960, two years prior to Ligeti’s “Poème.” (Ichiyanagi was Yoko Ono’s first husband.) Nor has the passage of time diminished interest in the object; 2013 saw the recording debut of composer Dan Trueman’s “120bpm,” written for the ensemble So Percussion, which employs “virtual metronomes”; in the liner notes they are described to be “clicking relentlessly, but reset by striking raw chunks of wood.”

A composer was, in fact, among the earliest benefactors of the metronome’s creator, Johann Nepomuk Mälzel: Ludwig van Beethoven glimpsed in the device a means to enact control over his time signatures. As time has passed, as the digital tick has gained insistence in our lives, as the device has gained prominence, it makes sense that it would be recognized as an instrument in its own right.

And this is the German translation:

Zeit Verändert Alles

Tick, Tick, Tick. Der Tick ist vielleicht das kleinste eigenständige Geräusch. Sicher, es fehlt dem Tick die brodelnde Qualität eines unterirdischen Brummens, jenem genormten Schall-Double, das Nebel, Hintergrund und Erscheinung suggeriert. Der Tick hat Dimension durch seine bloße Pixelweite, -höhe und -tiefe, der Tick ist ein Geräusch, außerstande, etwas anderes zu überschatten.

Trotz allem bleibt der Tick in einer Dimension knapp bemessen, nämlich der vierten: der Zeit. Der Tick ist so kurz, dass er schon in dem Moment, wo er beginnt vorübergegangen zu sein scheint. Das macht den Tick so wesentlich für die Einteilung der Zeit. Er kann die Zeit messen ohne eigenen zeitlichen Ballast ins Spiel zu bringen. Zeit verändert alles, wie wir wissen.

Zeit verändert alles, einschließlich der Zeit, die in der Musik wahrgenommen wird. Im Jahre 1965 wurde in Manhattan zum ersten Mal ein Stück des ungarischen Komponisten György Ligeti aufgeführt. Die „Poème Symphonique“ war drei Jahre zuvor entstanden: Ein Stück komponiert für ein Ensemble der Größenordnung eines Symphonieorchesters, 100 Personen stark. In diesem Falle jedoch wird jeder Teil von Ligetis Werk mit demselben Instrument gespielt, dem Metronom. Das Metronom ist dafür gedacht, Musikern das Einhalten bestimmter Tempi zu ermöglichen, und nicht, um selbst Musik hervorzubringen. Im Falle von Ligetis Komposition ist das Ergebnis eine einfache Kakophonie, die mit der jeweiligen Interpretation variiert. Man kann auf YouTube zahlreiche Aufführungen finden, von denen manche an eine Uhrmacher-Werkstatt nach Arbeitsschluss erinnern. Andere ähneln mehr einem wilden Nest zirpender Grillen. Als das „Poème“ 1965 sein Debut in Manhattan erlebte, beschrieben die Kritiker der New York Times das Stück als „Vorspeise“. Die kurze, wenig begeisterte Besprechung endete mit dem Kommentar: „Das war alles, 100 Metronome, die allmählich zum Stillstand kommen“. Etwa 15 Jahre später schrieb dieselbe Zeitung in einer Zusammenfassung über Ligetis Werdegang, dass dieser besonders durch seine Komposition „Poème Symphonique“ Anerkennung erworben habe. Fast 20 Jahre nach dem ersten Artikel wurde seine Komposition bei der New York Times als Beweis für sein „heimliches Genie“ hervorgehobenen: „zuerst erscheint die Komposition eher wie ein aufwändiger Witz und wirkt dann später merkwürdig anziehend.“

Es sei hier klargestellt, dass Ligeti nicht der Einzige war, der das Arbeitswerkzeug der Musiker in ein Instrument verwandelte. Er war nicht einmal der erste: Der japanische Komponist Toshi Ichiyanagi, 10 Jahre später geboren als Ligeti, hat seine eigene „Musik für Elektrische Metronome“. Das Werk entstand zwei Jahre vor Ligetis „Poème“. (Ichiyanagi war übrigens Yoko Onos erster Eheman). Das Interesse an dem Objekt Metronom hat im Laufe der Zeit nicht nachgelassen. Im jahre 2013 erschien eine Aufnahme des Stückes „120bpm“ des Komponisten Dan Trueman. Das Werk wurde für das Ensemble „So Percussion“ geschrieben, das virtuelle Metronome verwendet; in den Anmerkungen heißt es: „unnachgiebiges Klicken wird durch das Schlagen von rohen Holzklötzen unterbrochen.“

Schon der erste Förderer von Johann Nepomuk Mälzel war Komponist: Ludwig van Beethoven ahnte, das ihm das Gerät die Möglichkeit bieten würde, eine bessere Kontrolle über seine Zeitsignaturen ausüben zu können. So, wie die Zeit vorangeschritten ist, so, wie der digitale Tick sich beharrlich in unserem Leben festgesetzt hat und angesichts dessen, welche Bedeutung das Metronom erlangt hat, ist es sinnvoll, es als ein eigenständiges Instrument anzuerkennen.

More information at salvagione.com. Design by boondesign.com. German translation (from English) by Simone Junge. Initial project announcement: disquiet.com, theater-regensburg.de.

The Contingency of Listening (MP3)

Daniela Cascella and Salomé Voegelin have begun a show on the great British radio station Resonance 104.4 FM, as mentioned here on Saturday. After two broadcasts on Resonance’s radio signal, each show is to be collected online for broader distribution. The debut episode is now available for download, and it features Cascella and Voegelin talking about what drew them to write about sound, about how writing on sound differs from music criticism, and about the freedom they both feel in the endeavor given that neither is writing in their native language. Cascella is Italian and the author of En Abime: Listening, Reading, Writing (Zero Books, 2012). Voegelin is Swiss and the author of Listening to Noise and Silence: towards a Philosophy of Sound Art (Continuum, 2010). Both live in London. Perhaps the defining characteristic of the inaugural episode is how much it is a conversation: not a prepared dialog, but a discussion in which they ask questions of each other, questions in which the questioner and the questioned are not necessarily entirely sure of the answers (MP3). This lack of assurance is presented as much as an ideal representation of listening as it is of the duo’s shared curiosity, because they both focus on what they describe as the lack of the tangible in sound, the “contingency of listening,” as it is put, in which the experience is ephemeral, unlike, say, in the visual arts.

Download audio file (ora_part1_11-06-13-1.mp3)

Track originally posted for free download at ora2013. More on Cascella (above left) at danielacascella.com and Voegelin (right) at salomevoegelin.net. The Cascella image is from an interview with her at earroom.wordpress.com, as is the Voegelin image.

June 30, 2013

I Am Sitting in a Singularity Listening (MP3)

One of the fascinating premonitions of the proposed singularity is when the avant-garde concepts of the past are, literally, transformed into digital processes — when concepts become code. Such is the patch called “lucier.amh” by Christian Haines. Haines has attempted with this exercise in automated looping to reproduce the decay inherent in Lucier’s classic “I am sitting in a room listening.” In Lucier’s original, the sound of him saying the title words is heard over and over, each rendition a rerecording of the previous recording played back in the same room. The work has a signature sonic fraying, as words disolve into syllables and then into noise. Mark Morse has applied Haines’ patch in the following piece to the electric guitar, letting simple guitar phrases devolve as time proceeds. It is an enticing performance, in large part because looping is so often associated with accrual, with layering, with accumulation, but here it is used as a source of dissolution.

This is from Morse’s post on the recording:

I’m normally a bit of an anti-loopist these days, I guess because I spent many years looping and just eventually became a bit fatigued by the sound of it and the playing strategies that it traps you into, etc. Nonetheless these are a few loopy guitar improvisations through one of the example patches that comes with AudioMulch version 2.

It’s a patch written by Christian Haines called lucier.amh, and it’s supposed to kind of coarsely emulate the resonant frequencies techniques used in I Am Sitting in A Room, though here there are no real rooms involved: these are the resonant frequencies of one NastyReverb contraption and five two-second SDelays (along with a bit of “nice” reverb at the end of the chain, added by me, which I realize completely smooths over and destroys any remaining vestiges of Lucier’s intended soundworld, but…I don’t think I was ever aiming for that anyway).

This is a simple patch, but an interesting and useful way to degrade or erode a shortish loop. In each of these recordings I stop playing after about 3 minutes, which is a little too soon musically: if I’d had a bit more patience I could’ve paced the first five minutes better, but the sooner I stop adding new material, the sooner the loop can start to degrade, and that degradation is what these studies were about. So that means that in each study there’s an absence of development from the 3:00 mark to 5:00 minutes while I wait for the resonance to audibly kick in.

Track originally posted for free download at soundcloud.com/markemorse. More from Morse, whom some readers of this site might know better as (dj) morsanek, at morsanek.blogspot.com. He is based in Amsterdam, Netherlands.

June 29, 2013

More Free Music from Oval

More music has been posted for free download by Oval (Markus Popp): the 2000 album ovalprocess and his side of a 2011 split EP released with Liturgy, Oval-Liturgy. These follow five previous recent free downloads: Aero Deko, Dok, Pre/Commers, Ovalcommers, and Szenario. Get them all at oval.bandcamp.com. Ovalprocess is late-era glitch from one of the key acts to push that approach, all broken media and frayed sounds, while the Liturgy split is along the lines of his more recent efforts in producing, solo, music that sounds more like a post-rock band working through themes in a live setting.

ovalprocess by Oval

Oval-Liturgy Split EP (Oval Side) by Oval

Get them all at oval.bandcamp.com.

Cues: Rdio, Spotify; Writing Sound; Producer Reducer

◼ This Is Rdio Disquiet: I’ve started a pair of ambient stations/playlists at rdio.com and spotify.com, for any folks who subscribe to those services. These are in addition to the three setlists-by-accrual “Disquiet Carousels” over at SoundCloud.com.

◼ If a Setlist Plays in the Forest: Olivia Solon at wired.co.uk reports on a project involving a radio transmitter deep in a Scottish forest by name of Galloway. The music will play for 24 hours. “Those who want to hear it,” writes Solon, ” will have to head to the forest. There will be no repeats and the files will be deleted after they are played.” The music will include work by Severed Heads, The Herbaliser, Scanner and Stephen Vitiello, Dave Clark, Imogen Heap, and Richard X. The koan-probing DJs are Stuart McLean (aka Frenchbloke) and Robbie Coleman and Jo Hodges, the latter two of whom are artists in resident at Galloway Forest.

◼ Daniela Cascella and Salomé Voegelin have created a new broadcast series, titled Ora, about “Writing Sound” for Resonance104.5FM in England. After the program(me)s are heard on radio, they’ll pop up on the resonancefm.com website. The first one aired Thursday, June 27, 2013, with a rebroadcast scheduled today, June 29, after which it’ll pop up on the Resonance site. Here’s a description:

Writing Sound voices the relationship between listening, hearing, talking and writing – it puts forward a language that is part of the listening practice and challenges the nominal relationship between sound and words, naming and reference. It is language as the production of words, the material of language, in response to the material of sound, that invites listening as a material process also to uncover in language the process of listening, rather the source of what is being heard.

◼ Excellent interview with producer Rick Rubin (LL Cool J, Beastie Boys, Johnny Cash) at thedailybeast.com, especially in terms of his focus on simplicity. His emphasis on less being more is virtually required reading for anyone participating in this week’s Disquiet Junto project, which is based on subtraction-as-composition. Here is Rubin replying to an informedly leading question from interviewer Andrew Romano:

Q: So you don’t believe that, say, a great melody is necessarily part of a great song?

A: No, no. I think one of the things that really drew me to hip-hop was how you could get to this very minimal essence of a song—to a point where many people wouldn’t call it a song. My first credit was “Reduced by Rick Rubin.” That was on LL Cool J’s debut album, Radio. The goal was to be just vocals, a drum machine, and a little scratching. There’s very little going on.

◼ Decade of SoundWalk: July 1 is the final day for proposals to participate in the 10th annual soundwalk.org sound art festival in Long Beach, California. Last year I ran a panel discussion at SoundWalk, and the whole event was a blast.

June 28, 2013

Ambient Classical (MP3)

“I’m beginning to feel like this blog should be called 52 months at the rate I’m going,” writes composer Madeleine Cocolas. She is commenting on the status of a projected series of 52 weekly projects throughout 2013. She is also being a little unkind to herself, a little disingenuous, since as of the final week of June her effort has yielded 20 of the 26 pieces she might have completed by now. That is a fairly solid accomplishment.

Cocolas was born in Australia and lives in Seattle (where the above photo was shot by her). Her “Week 20 Project” is tagged “ambient classical,” a fitting association. It’s an elegant work, a spare piano line lingering amid a deep echoing space, shimmering shards heard deep in the background. In time the space between shard and piano is filled with an additional line, a deep swell of sound that gently nudges past the elegiac stasis of repetition toward something more melodic, if waveringly so.

She writes, in part, of the piece:

For my Week Twenty Project, I again trawled through the old hardrive I told you about a few weeks ago and found a little piano loop I wrote back in 2005 that I’ve incorporated into this weeks’ project. It’s the repetitive piano background that starts the piece off and plays throughout. I’ve also got it playing in reverse through the piece as well.

Around the 45 second mark I’ve added some more piano and some bass clarinet (a stunning instrument that I really haven’t delved into properly yet). I think the result is a pretty calming and tranquil peace that is also hopefully filled with gentle optimism.

Track originally posted for free download atsoundcloud.com/madeleine-cocolas. More from Cocolas at madeleinecocolas.blogspot.com, where she is documenting her 52-week project.

June 27, 2013

Disquiet Junto Project 0078: Less Sound, More Music

Each Thursday at the Disquiet Junto group on Soundcloud.com a new compositional challenge is set before the group’s members, who then have just over four days to upload a track in response to the assignment. Membership in the Junto is open: just join and participate.

The composition at the heart of this week’s project is mentioned prominently in the Anton Chekhov short story “The Black Monk”:

One day he was sitting on the balcony after evening tea, reading. At the same time, in the drawing-room, Tanya taking soprano, one of the young ladies a contralto, and the young man with his violin, were practising a well-known serenade of Braga’s. Kovrin listened to the words — they were Russian — and could not understand their meaning. At last, leaving his book and listening attentively, he understood: a maiden, full of sick fancies, heard one night in her garden mysterious sounds, so strange and lovely that she was obliged to recognise them as a holy harmony which is unintelligible to us mortals, and so flies back to heaven. Kovrin’s eyes began to close. He got up, and in exhaustion walked up and down the drawing-room, and then the dining-room. When the singing was over he took Tanya’s arm, and with her went out on the balcony.

This assignment was made in the evening, California time, on Thursday, June 27, with 11:59pm on the following Monday, July 1, 2013, as the deadline.

These are the instructions that went out to the group’s email list (at tinyletter.com/disquiet-junto):

Disquiet Junto Project 0078: Less Sound, More Music

The 78th weekly Disquiet Junto project revisits the most popular project in the year and a half thus far of the ongoing Disquiet Junto series. It’s a shared-sample project. Everyone will work from the same source audio, which is provided below. You will take the provided sound sample and from it make an original work. You will do this only by subtracting sound from the sample. You won’t add anything to it. You won’t slow it down. You won’t speed it up. You won’t cut it up, and you won’t otherwise reorganize its contents. You won’t play it backwards. You will only “remove.” The word “remove” is up for interpretation — but generally speaking, I’d say that it means various acts of lowering the volume of a narrow or wide band of the audio spectrum for either a short or long period of time. And, of course, “lowering the volume” can be interpreted to mean muting outright. The act here of “removing” is the sonic equivalent of sculpting something from a solid block.

The track that will be the focus of our collective effort is a 1902 recording by the Edison Symphony Orchestra of “Angel’s Serenade,” or “La Serenata,” by composer Gaetano Braga. This link goes to the source MP3:

Deadline: Monday, July 1, 2013, at 11:59pm wherever you are.

Length: Your piece will, due to the nature of the assignment, be the exact same length as the original recording on which it is based: two minutes and seven seconds (2:07).

Information: Please when posting your track on SoundCloud, include a description of your process in planning, composing, and recording it. This description is an essential element of the communicative process inherent in the Disquiet Junto.

Title/Tag: Include the term “disquiet0078-minusmusic” in the title of your track, and as a tag for your track.

Download: Please consider employing a license that allows for attributed, commerce-free remixing (i.e., a Creative Commons license permitting non-commercial sharing with attribution).

Linking: When posting the track, be sure to include this information:

More on this 78th Disquiet Junto project, in which sound is removed from a century-old Edison Symphony Orchestra recording, at:

http://disquiet.com/2013/06/27/disqui...

This track a reworking of a 1902 recording by the Edison Symphony Orchestra of “Angel’s Serenade,” or “La Serenata,” by composer Gaetano Braga. The source audio is from this URL:

http://archive.org/details/EdisonSymp...

More details on the Disquiet Junto at:

http://soundcloud.com/groups/disquiet...