Mark Sisson's Blog, page 227

April 1, 2016

My New and Improved Diet

People are always asking me what I eat on a typical day. Though I’ve done these posts in the past, I’m always a bit hesitant of doing any more. For one, I’m a boring dude. I like what I like, and it’s all pretty typical stuff you’d see in anyone’s (who cares about real food) kitchen. Two, this is the eating style that works for me. Just because I eat a particular food at a particular time of day doesn’t mean you should eat the same way. But because I’m always tweaking things, and some of you apparently find that interesting, I’ve relented.

People are always asking me what I eat on a typical day. Though I’ve done these posts in the past, I’m always a bit hesitant of doing any more. For one, I’m a boring dude. I like what I like, and it’s all pretty typical stuff you’d see in anyone’s (who cares about real food) kitchen. Two, this is the eating style that works for me. Just because I eat a particular food at a particular time of day doesn’t mean you should eat the same way. But because I’m always tweaking things, and some of you apparently find that interesting, I’ve relented.

So let’s get to it: a day in the dietary life of Mark Sisson.

Now, I’ll alternate every other day between eating three square meals and eating in a compressed eating window.

Breakfast.

French press coffee brewed with reverse osmosis-treated maple water.

20 quail egg omelet (or a scramble with camel colostrum). Note: if you’re out of quail eggs, you can substitute 1/6 ostrich egg or 2 goose eggs.

After breakfast, I do my hot-and-cold exposure ladders. Here’s how it works:

Alternate between jumping in my unheated pool (about 50° F, give or take a few) and immersing myself in a trough of glowing embers. A minute in the pool, 5 seconds in the embers, then back in the pool for another minute. Repeat until the embers have all gone cold. A quick rinse and I’m refreshed and warm and ready to work.

Lunch is still the Big Ass Salad. I’ve got a few favorite variations:

Mulberry leaf silkworm salad. Shredded mulberry leaf tossed in a mulberry vinaigrette. Sometimes I’ll throw in a few molting worms for extra crunch. No moths, though (too dusty).

Shredded root salad. If I’m not feeling like eating all that bulky roughage, I’ll go for my famous shredded local root salad. Lately I’ve been shredding over seven varieties of turmeric, two types of galangal, American ginseng, Siberian ginseng, red ginseng, fresh astralagus root, and fresh ashwagandha root all tossed in a kokum oil vinaigrette, all grown by my buddy the next street over. He’s got a great setup, a “climatehouse” with over a dozen rooms, each emulating a different subclimate. From tundra to ice cap to temperate rain forest to tropical rain forest to subarctic to Mediterranean, he could raise Dengue fever-carrying mosquitoes and penguins and grow ayahuasca if he wanted. I’m seriously jealous.

Negative calorie salad. I’ve been playing around with eating meals that result in negative caloric intake. Cooked-and-cooled-and-cooked-and-cooled-and-cooked-and-cooled-and-cooked-and-cooled potatoes, jerusalem artichokes, jicama, shirataki noodle tossed in a yacon syrup dressing. My weight has increased, but it’s just colonic bulking from all the prebiotic fiber (confirmed with colonoscopy; camera barely fit!). Pure lean colon mass. I’ll eat the negative calorie Big Ass Salad to cancel out any overfeeding. If I’m extremely, painfully full after a big dinner, I’ll even eat one just to burn up some of the excess calories I just consumed. It’s a powerful tool. If I had any weight to lose, I’d eat a couple of these on my fasting days to kickstart the fat loss.

If I get hungry between meals, I’ll snack. Apple slices dipped in mortar-and-pestle-ground sprouted Brazil nut butter. Skin-on beef jerky dried in the midday sun as the cow is humanely bled out to retain and maximize vitamin D content (sadly not grass-fed). Hyper-ripe mango, which looks unappetizing (brownish, oozing, foul-smelling, moves and squirms in your mouth) but is so alive and teeming with beneficial bacteria, yeasts, fungal networks that it’s on the cusp of sentience. But this doesn’t happen much.

Dinner is pretty standard stuff.

Piece of meat, veggie, occasionally a starch. Last night, I had braised dugong flipper (a unique mix of omega-3s and collagen) with fiddlehead ferns sautéd in isolated trans-palmitoleic acid (a trans-fatty acid unique to dairy) and a side of broccoli almost-sprouts (where you stop the sprouting process just before it sprouts, thereby capturing the energy and essence of life). Standard, as I said.

I’m developing a fantastic new seafood sauce I often use at dinner. Instead of your typical olive or avocado oil, the fat comes entirely from extra virgin slurry of krill larvae. And I don’t use late-stage krill larvae, like all those other guys; I make my slurry exclusively from krill nauplius, the very first stage of larvae after they emerge from the eggs. You can use this as a salad dressing, a sauce for meat and veggies, drizzled over yogurt, or even straight up on a spoon for the omega-3s.

I’ll have an entire bottle of wine from Dry Farm Wines with dinner, but I add liposomal glutathione to every glass so that my liver’s able to quickly detoxify the toxic ethanol and highly-toxic acetaldehyde. I’ve tried the liposomal glutathione trick with other types of alcohol and can get up to a pint of Scotch without feeling anything. Two pints and I can still drive the winding curvy canyon roads of Malibu without issue. Great hack!

Other days, I eat in a compressed eating window. You know this about me. I’ve discussed it before. But rather than do a 6 or 7 hour eating window, I decided to compress it even further: down to 20 minutes.

Sure, that 20 minutes is stressful, chaotic rush to cram all the day’s food in my mouth. But it’s an acute stressor, not a chronic one, and thus hormetic. The rest of the day, I’m free to focus on work, play, training, and whatever else I want to do without my hypothalamus nagging me to eat. It’s great. I’m currently writing this post as I gear up for my eating window. To prepare, I do a glycogen depleting workout. I want to clear room for everything coming in, so I have to hit every single muscle until exhaustion. I’ll also do an hour of extremely tricky puzzles, crosswords, and other brain-training to tap into and deplete my liver glycogen.

Throughout the day I’ll drink a special probiotic tea I get from a stand at the Malibu farmer’s market. The stand’s actually an organic vegetable stand and the way they make the tea is incredible. Directly after harvest, the vegetables (various greens, root vegetables like carrots and beets, broccoli, cabbage, etc—your basic veggies) and the farmers’ hands are rinsed to remove the dirt. They save and bottle this rinse water, and add a few shakes of fresh grass-fed steer manure, so it’s chock full of both soil-based and manure-based probiotics. It’s earthy and loamy and barn-y and a little musty—just the way a good probiotic tea should be.

One last thing I’ve been playing with is taking a 1/2 teaspoon of broad spectrum pesticides for the hormetic effect of toxin exposure. Any standard one from the garden store will do as long as it targets vertebrates, invertebrates, fungus, and plants. This isn’t every day, of course. Just once or twice a week.

And that’s about it! I love the way I eat, and even though you don’t have to eat like I do, it’s always helpful to see how others are making this Primal thing work. I hope I’ve inspired you as much as you all inspire me.

Speaking of which, what about you? What’s a typical day of eating look like for you?

Thanks for reading. Take care!

March 31, 2016

How to Develop Emotional Resilience in the Modern World

Job stress, social conflict, illness (sometimes serious illness), financial hardship, our children’s struggles, a move across country, a divorce, a death of a loved one…they’re all events that can test our mental fortitude or—in more extreme cases—leave us emotionally adrift. Some people turn into a puddle during a critical emergency, while others jump in the middle of it to save the day. Yet, watch those same people face a protracted struggle like the death of a spouse or a child, and the one who managed the momentary crisis may have a much harder time. Adversity varies and challenges us in different ways. But our ability to endure and bounce back from stress, struggle, and loss is what emotional resilience is all about. What can our ancestors’ examples teach us about psychological hardiness and mental fortitude?

Job stress, social conflict, illness (sometimes serious illness), financial hardship, our children’s struggles, a move across country, a divorce, a death of a loved one…they’re all events that can test our mental fortitude or—in more extreme cases—leave us emotionally adrift. Some people turn into a puddle during a critical emergency, while others jump in the middle of it to save the day. Yet, watch those same people face a protracted struggle like the death of a spouse or a child, and the one who managed the momentary crisis may have a much harder time. Adversity varies and challenges us in different ways. But our ability to endure and bounce back from stress, struggle, and loss is what emotional resilience is all about. What can our ancestors’ examples teach us about psychological hardiness and mental fortitude?

Genuine resilience demands a deep level of acceptance—the acceptance that even if some things in life shake or shatter us, that’s not the end of our story. Just as our physical bodies are vulnerable and resilient, so are our mental selves. We can survive a horrible car accident with damage to multiple organs and limbs—and still heal to a large, if not complete, extent. We can suffer a stroke—and more or less regain full functioning as other parts of our brain take over tasks previously handled by the damaged section. In the same way, we can recover from great emotional damage.

Let me be clear though. I would argue that emotional resilience isn’t about pushing down feelings or living in denial. There’s a mammoth-sized gap between being forbearing and simply unfeeling. Resilience isn’t seated in an original sense of inviolability, but in a commitment to and capacity for healing and continuing. Think adaptability rather than invulnerability.

I think we all recognize that Grok and his kin experienced loss and travail in ways modern first-world citizens can only imagine. Emotional resilience was truly a survival (not to mention survival of the fittest) mechanism. Child mortality and accidental death from animals or the elements were anticipated, albeit tragic, occurrences. No one was shielded from seeing the likes of a predator’s mauling, the face of starvation or the ravages of random disease.

Likewise, there were other shifts. People came and went from band to band. Others migrated. When you said good-bye for the season or for a migratory trek, you truly didn’t know if you’d ever see that person again. (And obviously there were no means of communication beyond in-person contact.)

We might be confounded as to how they could weather this amount of loss and uncertainty. It’s easy and convenient to just assume they were somehow less emotionally evolved—that they were less affected by these upheavals and tragedies than we moderns would be. This is false, of course. We don’t want to think of that kind of pain in anyone, considering our natural, poignant inclinations toward empathy certainly don’t make it a pleasant recognition. Nonetheless, when we fully acknowledge the capacity for others’ pain (in prehistory or on the other side of the globe today), we not only grasp others’ humanity, but we can see and honor what allows them to move through life in spite of what they’ve weathered.

Compared to the struggles of our primal ancestors, we might have it pretty easy. We may not be fending off daily threats to the survival of ourselves and our kin, but we have our own modern problems that can wear down our mental stamina and emotional equilibrium. Likewise, none of us are spared the eventual human losses. Aspects of the human struggle are truly timeless.

When we accept that emotional resilience isn’t about unconsciousness or desensitization, it breaks open the question: What really helps us weather life’s travails?

The works of various psychologists are often cited as a model for assessing (or a guide for strengthening) a person’s capacity for resilience. Although much research and models focus on children, I think most of us would say these domains and dimensions are just as relevant to our emotional health in adulthood. They stress the importance of “protective factors” that shore up psychological health and offer us both social resources and psychological reserves when adversity does hit.

They revolve around the idea of a “secure base” with elements like fundamental physical health, solid family and friend relationships, engaging educational/enrichment opportunities, talents and interests, positive values, and social competencies that allow for self-care and the need for communication.

The more secure we are in these essential areas, the idea goes, the more resilient we will be to various challenges that come down the pipe. In that way, the more we can shore up these various dimensions of life, the better off we’ll be.

Likewise, research suggests better communication and problem-solving skills as well as emotional regulation and executive planning abilities (creating a plan and following it) enhance our capacity to deal with psychological stress and crisis.

Clearly, these all would have figured into the picture for Grok and his kin. Social relationships, in particular, would have offered support for both the emotional toll and the logistical details (e.g. help with daily chores) of bouncing back from major events.

We lean on others for literal help with the efforts and tasks necessary to get through the day when we’re coping, but we also depend on the depth of the human bond itself to get us through those times. Just as we’re wired to empathize with others, we’re also wired to receive empathy.

Instead of getting caught up in the whirlwind of daily busyness, we can take the time for these dimensions that strengthen us. Just as we invest financially for our future security, we can invest in our emotional security by prioritizing social connections. We can keep in close and frequent touch with friends and extended family by calling or enjoying a night out or a weekend trip together. We can expand our social networks and invite new people into our lives.

We can deepen our sense of identity by pursuing outside interests and hobbies. Life is about whom we love and what we enjoy doing. The more we invest in our own enrichment, creativity and self-development, the more solid we are in ourselves and the stronger we can be in the face of stress or loss.

And let me add one of my favorite points here. For hunter-gatherers, the picture of identity and connection went beyond just human social networks. Their relationship with the natural world was an important part of their identity, a key element of communal belonging, and a supportive element for their psychological resilience.

Can you imagine not just believing intellectually, but believing both spiritually and emotionally, that nature was something to which you belonged—that it was an anthropomorphized force you were obliged to venerate and participate in as its kin? While I’m sure Grok might have better language (and stories) to illustrated this, you get the general idea here. That sense of deep, original belonging offered both a comfort and structure, and the psychological vestiges of this long-practiced belief system are part of our own psyches. Evolutionary psychology as well as the relate theory of biophilia take up this dimension of emotional well-being.

When we view our lives and those of the people we care about against this larger, cosmological (or simply evolutionary) backdrop, the toils and tragedies of regular life have a meaningful place. Modern humans generally view themselves as an exception to nature’s laws—as destined conquerors or shrewd hackers to the system. The result is we either feel like strategizing owners of the natural world or an unfortunate scourge upon it. Any possibility of true belonging and mutual consolation within the natural world disappears.

Living Primally for many people means cultivating something of that original relationship and benefitting from that sense of integration. There’s a grander, enigmatic power beyond us, and we all return to it. Those we love when lost are incorporated into it again in a way that isn’t just the literal dust to dust but is part of the mythic dance of life our ancestors understood. Grief had a clear and ritualistic role, and it too was communally revered. Ceremony and story placed feelings in a larger collective container. We can reclaim those rites for ourselves in our own lives however they make sense for us.

Finally, as I mentioned earlier, resilience isn’t about being emotionally impenetrable. Nor is it about simply being strong and solid enough to preserve the self that already exists. It’s not even about the grit to supposedly resist or keep out the negative effects of crisis. It’s about the ability to incorporate adversity and to grow from it.

Beyond the emotional regulative strategies and social supports we can use when we’re stressed or overcome, we can also cultivate a fundamental flexibility and adaptability within ourselves. Meditation and mindfulness practices can be helpful to this process. Exploring approaches like Stoicism’s negative visualization can help us let go of outcomes and our attachment to our will in exchange for peace with what is present now.

Because the fact is, things do fall apart. None of us are guaranteed an easy ride in life. The more we can let go of the idea that we deserve to not feel stress or pain or grief or frustration, the healthier we’ll be. Unconditional acceptance—for circumstances and the emotions we’ll go through in responding to them—is perhaps the ultimate form of resilience.

In the face of the most serious adversities and losses, we will come unglued to a certain extent. If we can see that as a useful adaptive response, we can work with it. If we put all our energy into resisting what is and how we’re feeling, we’ll suffer more than we need to. Grok and other traditional groups understood this far better than modern Western humans.

Maybe the most adaptable strength is the willingness to feel all there is to feel in a human life. It’s the willingness to change and be changed by circumstance. The less we clutch our current relationships, our identities, our locations, our jobs, our will and belief about how it all should go, the more emotionally buoyant we’ll be.

Not surprisingly, we find ourselves back at the beginning of the circle with that old Primal principle of advantageous adaptation.

Thanks for reading, everyone. I’d love to hear more about your understanding of emotional resilience. Share your thoughts in the comment board, and enjoy the end of your week.

Like This Blog Post? Subscribe to the Mark's Daily Apple Newsletter and Get 10 eBooks and More Delivered to Your Inbox for FREE

March 30, 2016

How Going Primal Can Help With 5 Common Genetic Mutations

As I mentioned earlier this year, our personal ancestry can help determine how we respond to certain dietary, behavior, exercise, and lifestyle patterns. The big question remaining is this: does going Primal mesh with some of the more common polymorphisms? Yes. The Primal Blueprint is a living document. Its foundation rests on pre-agricultural human evolution, but by remaining flexible and offering ample room for personalization, it acknowledges the fact that evolution has continued to occur.

As I mentioned earlier this year, our personal ancestry can help determine how we respond to certain dietary, behavior, exercise, and lifestyle patterns. The big question remaining is this: does going Primal mesh with some of the more common polymorphisms? Yes. The Primal Blueprint is a living document. Its foundation rests on pre-agricultural human evolution, but by remaining flexible and offering ample room for personalization, it acknowledges the fact that evolution has continued to occur.

Let’s take a look at five genetic mutations and how the Primal way of eating, living, and moving can help mitigate their downsides.

1. Aerobic exercise “non-responder” genes

By now, you’ve likely heard of exercise “non-responders”—people who don’t respond to cardio the way they’re supposed to. Rather than experience health and fitness benefits, an exercise non-responder might see no changes, or even detrimental ones when they exercise. These non-responders seem to cluster in families, an indication of genetic influence.

Aerobic exercise non-responders are the most common. Whereas about 85% of the population experiences big improvements in VO2max after sustained endurance training, about 15% do not. They can work hard, about as hard as the others, and follow the same protocol yet experience almost no improvement to their oxygen consumption rates. In some people, endurance training can even degrade their health. They actually experience worsened insulin sensitivity, lower HDL, and elevated blood pressure when they train.

If a person is an aerobic non-responder, they do the work but see little benefit unless they really up the intensity and duration of their aerobic training. This means they have to lapse into chronic cardio territory just to get the “benefits,” and that carries its own set of problems as I’ve discussed many times before. Since animal studies suggest that exercise non-responders are more reliant on glucose for energy, that their blood sugar levels decline more rapidly and they can only run about half as long during endurance exercise, increasing the intensity and duration isn’t sustainable.

What does seem to work is high-intensity training. The experts claim that non-responders need high-intensity, high-volume training to see results, but when you examine the study designs you find they haven’t tested the kind of high-intensity, low-volume training I promote. For instance, sprint interval training works for exercise non-responders. They may have to increase the number of workouts they do, but at least they’re getting somewhere without having to spend several hours a day in that elevated HR zone.

There’s also a psychological component to movement that most training programs neglect: is it enjoyable? If you’re a non-responder with low blood sugar seeing very few results, you’re not going to keep plodding along the treadmill. But that same non-responder may have a blast playing Ultimate Frisbee, or learning a martial art, or breaking through the clouds to reveal a stunning sunrise on an early morning hike. Incorporating, or indeed focusing on play as the proximate goal of training and movement is a winning strategy for people with a genetic aversion to exercise.

2. Genes associated with soft tissue injuries

This is me. Based on my genetics, I have an increased risk of incurring soft tissue injuries like arthritis and the various tendinopathies.

But those genetic polymorphisms are linked to soft tissue injuries across the population. What’s the “population” doing?

They’re eating inflammatory diets. They’re not exercising or moving much at all, and when they do, they do it wrong. If they’re dedicated exercisers, they probably train too much. They’re not eating the whole animal. That’s how I used to be, and sure enough, I ended up with a steady stream of soft tissue injuries. When I went Primal, they stopped.

Going Primal helps in multiple ways:

By promoting correct movement patterns. Less sitting (so you don’t get so stiff and creaky), more full body compound movements (so you’re not isolating your tissues and placing undue stress on them), less chronic cardio (which increases inflammation and chronic loading patterns), more strength training (placing acute loads onto tissues with plenty of recovery time promotes stronger tissues).

By reducing systemic inflammation. Fewer unnecessary carbs, more anti-inflammatory plants and spices, better sleep, more omega-3s, and an increased awareness of stress and the danger of chronic inflammation lead to less of it.

More dietary collagen. Regular diets don’t provide enough dietary collagen to meet the body’s daily glycine requirements. Since glycine contributes to rebuilding and repairing collagen in the body (cartilage, tendons, ligaments, fascia), inadequate collagen can open you up to soft tissue injury. By promoting the consumption of bone broth, gelatinous meats, and collagen supplements, the Primal eating plan usually leads to greater collagen consumption.

3. PUFA metabolism variants

FADS1 controls elongation of shorter-chain polyunsaturated fats into their longer-chain counterparts. People with certain FADS1 mutations are bad at converting alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) into the longer-chained (and extremely important) omega-3s EPA and DHA. In pregnancy and nursing, these mutations can lead to impaired levels of omega-3 in the breastmilk and lower IQ in the fetus. To get enough of the physiologically relevant forms, they need to eat them directly.

If there’s one thing the Primal way of eating does well, it’s promote the consumption of healthy animal fats containing long-chain PUFAs. Indeed, certain people simply need to eat more fatty fish to be healthy. I’m one of them, likely owing to my Scandinavian ancestors coastal living and heavy reliance on marine foods.

Other PUFA metabolism variants affect the conversion of linoleic acid into inflammatory compounds. If you have these variants, higher intakes of linoleic acid (around 17 grams per day in one study, which is typical for people eating regular modern diets) are associated with breast and prostate cancer.

In the end, no one benefits from excessive intakes of omega-6 PUFAs and some are harmed. On the other hand, eating adequate amounts of omega-3s through marine foods and pastured eggs is safe for everyone and especially crucial for some. Going Primal takes care of all that by eliminating the most concentrated source of linoleic acid (processed seed oils) and emphasizing regular fatty fish consumption. The modern western model of high omega-6 intake through seed oils and low omega-3 intake is bad for every polymorphism; going Primal reverses that.

4. Glutathione synthesis genes

Whether it’s countering airborne pollution, detoxifying toxins like ethanol, or regenerating immune cells, glutathione is the premier antioxidant in our bodies. Unfortunately, some people just don’t make enough glutathione to deal with modern insults. Multiple genes determine how much glutathione we synthesize. Among them, GCLC is the gene regulating the cysteine-to-glutathione conversion pathway. GCLC-knockout mice with the cysteine-to-glutathione pathway severed normally develop severe steatosis and die from total liver failure within a month. Giving them a concentrated source of n-acetylcysteine (NAC), a widely available and inexpensive supplement, restores some glutathione synthesis by providing the necessary building block and rescues them from liver failure. They’re not rescued from death—the mice do end up with chronic cirrhosis of the liver—but they live longer.

The Primal eating plan includes many of the richest sources of cysteine and other glutathione-boosting foods, like whey protein and dietary flavonoids found in colorful fruits and vegetables.

5. MTHFR mutations

Forget any other diet. With its forests of broccoli, spinach, and asparagus and the acknowledgment of liver’s nutritional supremacy, the Primal way of eating can be exceedingly rich in folate. This makes it a great choice for MTHFR mutation carriers with an impaired ability to convert folic acid to folate. Folic acid, the most common supplemental form of the vitamin, can work for folks without a MTHFR mutation, but the form of folate found in food is the most helpful for people with a mutation.

What about veganism, Sisson? Isn’t that going to be ideal? Sure, vegans—at least the ones who actually eat vegetables—have the biggest folate intakes of anyone. But there’s another nutrient whose requirements are often elevated in MTHFR people: B12. And because B12 is only found in animal foods, vegans are almost guaranteed to be deficient without supplementation. So when it comes to correcting the common deficiencies inherent to MTHFR polymorphisms, going Primal helps.

There are other polymorphisms—too many to cover. But these were five that jumped out at me. What about you, folks? Got any questions or comments about these or other genetic variants that interact with your Primal lifestyle?

Thanks for reading.

Like This Blog Post? Subscribe to the Mark's Daily Apple Newsletter and Get 10 eBooks and More Delivered to Your Inbox for FREE

March 29, 2016

8 Primal Rules for Building Better Bones

Strip away the skin, fascia, muscles, organs, blood vessels of a human and you’re left with the bones: the foundation providing passive structural support. Many people accept that we can affect and even control the health of the rest of our tissues. Muscles? Just lift. Cardiovascular system? Do some cardio and lose weight. Teeth? Stop sugar. But bones just wear down the older you get. Everyone knows it. And sometimes bones just break. There’s nothing you can to prevent it and nothing you can do to improve your healing except wait and hope. If you want stronger bones, you’ll need some pharmacological assistance provided by a white coat-clad adult wielding a prescription pad.

Strip away the skin, fascia, muscles, organs, blood vessels of a human and you’re left with the bones: the foundation providing passive structural support. Many people accept that we can affect and even control the health of the rest of our tissues. Muscles? Just lift. Cardiovascular system? Do some cardio and lose weight. Teeth? Stop sugar. But bones just wear down the older you get. Everyone knows it. And sometimes bones just break. There’s nothing you can to prevent it and nothing you can do to improve your healing except wait and hope. If you want stronger bones, you’ll need some pharmacological assistance provided by a white coat-clad adult wielding a prescription pad.

But bones aren’t inert. They are living metabolic tissue. And though we can’t tell them what to do directly, they grow—or diminish—in response to the signals we send. What kind of signals should we be sending?

1. Lift hard and move quickly

Bones respond to intensity. Forceful impacts, heavy weights, high mechanical loading—these are a few of your osteoblasts’ favorite things. They are unmistakable signals that trigger your bones to begin fortifying themselves.

In one study, researchers attached activity monitors to the hips of adolescent boys and girls. As they went about their week, the monitors tracked their exposure to forceful impacts. People whose hips experienced impacts of 4.2 Gs (activities like 10 minute mile runs or 15 inch box jumps qualify) or greater had the sturdiest hips. Next, they attached monitors to a group of women over 60 and ran them through an aerobics class consisting of brisk walking and box stepping. None of the older women experienced an impact over 2.1 Gs, yet they still saw bone density benefits.

Old bones respond to the same training signals. For instance, older endurance runners have lower bone density than age-matched sprinters, and senior athletes who engage in high-impact activity have higher bone density.

But older adults don’t have to join CrossFit to start seeing benefits to their bone density. Another study found that premenopausal women aged 35-50 who hopped in place 20 to 40 times a day (broken up into two sets of 10 or 20 with 30 seconds of rest in between hops) for 16 weeks experienced improvements to their hip bone density; those hopping 40 times a day saw bigger improvements. That’s very doable. And if you’re a postmenopausal woman (at greater risk for osteoporosis than premenopausal), you can throw on a weight vest when you do your hops.

The very best type of training for all ages is a combination of “impact training” and resistance exercise.

With regards to changes in bone density, exercise is site specific. Only the bones you subject to stress will respond.

2. Animal protein is safe and good to eat, so chow down

Go to any online vegan community and you’ll hear that animal protein leaches calcium from our bones. To support this assertion, they’ll cite studies showing that increased meat intakes lead to increased urinary output of calcium. So, is that steak you ate yesterday making you piss out desiccated femur?

No. Increased protein intake actually increases calcium absorption, and researchers who’ve looked into the situation closely conclude that, as bone health is linked to lean muscle mass, activity levels, and physical strength, the average protein intake is inadequate for optimal bone health especially among the elderly. If anything, “more concern should be focused on increasing fruit and vegetable intake rather than reducing protein sources.” Meanwhile, older men with the lowest protein intakes tend to have the greatest bone loss.

The reverse is true. Animal protein protects and strengthens bones and you should make sure to eat enough of it if you’re interested in preserving and/or building bone health.

3. Dairy helps, so give it a chance if you can

Dairy gets a bad rap. It’s “acidic.” It “leaches calcium” from your bones. You “can’t absorb” the calcium it does contain.

Nonsense.

Dairy actually isn’t acidic, nor does it leach calcium from the bones. And dairy-bound calcium is perfectly absorbable by humans. Most serious researchers recommend that older people at risk for osteoporosis consume more dairy, not less. In fact, people who can’t consume dairy because of an allergy have lower bone mineral density. Upon desensitization therapy and resumption of dairy consumption, bone mineral density recovers.

For optimal results, eat dairy that contains additional bone-friendly nutrients, like gouda cheese (with vitamin K2) or yogurt/kefir (which seem to induce more favorable changes to bone metabolism than unfermented dairy).

4. Maintain good sleep hygiene

Yeah, yeah. Sleep’s important, Sisson. We get it. But allow me to display just how high quality sleep—or the lack thereof, rather—affects bone health.

In older folks, self-reported sleep duration is inversely associated with osteoporosis. Less sleep leads to greater bone loss. More sleep protects against it.

Melatonin, the hormone that induces sleepiness at night, plays a huge role in bone metabolism. For instance, removing a rat’s pineal gland (which produces melatonin) significantly lowers their bone mineral density.

Obstructive sleep apnea, a disorder characterized by frequent cessations of breathing during sleep and an overall lower quality of sleep, is independently associated with low bone mineral density.

Too much or too little sleep are both linked to osteoporosis, with daily sleep durations of 7-8 hours, 9-10 hours, and 10 hours all showing a relationship to low bone mineral density.

We can’t know if this is a causal association, of course. Osteoporosis and one’s sleep needs may have a common determinant. But given the role melatonin plays in bone metabolism, optimizing sleep and circadian rhythm is a good idea. Either way, lack or excess of sleep is probably an indication that bone health may be compromised.

5. Drink mineral water

Historically, all water was mineral water. Whether it came from mountain springs or local wells, water came imbued with magnesium, calcium, and other trace minerals. But water loaded with minerals like calcium and magnesium is hard water; it’s bad for lathering soap, it leaves mineral films on dishes and pans, it can gunk up plumbing, and it has a distinct taste (which means “tastes bad” to many people). Thus, most tap water is softened and most bottled water is glorified tap water, filtered to remove “impurities” (which include minerals). And some people, fearing fluoride and other nebulous elements, drink distilled or reverse-osmosis filtered waters containing essentially no minerals at all. This leads to lower bone-friendly mineral intakes and a host of health issues (PDF).

Meanwhile, areas with high mineral content tap water tend to have lower rates of many degenerative diseases, including osteoporosis (PDF). Calcium in mineral water is highly bioavailable, equivalent to the calcium in milk. Magnesium, too. Both minerals are extremely important for bone health and mineral water is an effective, delicious way to obtain more of them. You don’t even have to change your behavior much. You’re already drinking water; it’s a fundamental requirement for biological organisms. Just drink a different kind of water. I suggest Gerolsteiner, a German brand loaded with calcium and magnesium that comes in glass bottles.

A mineral water habit can get expensive, though. Consider making your own.

6. Get enough of these specific nutrients and foods

Melatonin: Getting plenty of full natural light when you wake and throughout the day, avoiding blue light in the evening, and getting to sleep at a normal, consistent time promote healthy melatonin production, but supplemental melatonin has also been shown to improve bone metabolism and health and even counteract osteopenia. Are the people who benefit most from supplementation doing everything they can to optimize circadian health? Probably not. Does melatonin work? Yes. Just make sure to take it when you’d normally make it—an hour before bedtime.

Cod liver oil: If you want to supplement vitamin A, stick to cod liver oil, which has the correct pre-formed retinol form and enough vitamin D to balance your intake. Isolated vitamin A supplementation without concomitant vitamin D tends to perform poorly, while high retinol levels achieved via cod liver oil do not contribute to poor bone health.

Blackstrap molasses: For a triple whammy of bone supporting nutrients, have a tablespoon of blackstrap molasses. Just one will give you 180 mg of calcium, at least 48 mg of magnesium (and I’ve seen brands that give almost 100 mg per tablespoon), and about 20% of your daily copper needs.

Gelatin or collagen: People don’t often realize that collagen makes up a significant portion of the bone matrix. Without collagen present, bone would be overly hard and likely brittle (PDF). Collagen provides elasticity, not enough that you could make the Fantastic Four but enough that your tibia doesn’t shatter at the slightest provocation. I prefer gelatin over collagen hydrolysate because you can use the former to make fantastic sauces, curries, and gravies, but either one provides the basic collagenous building blocks that we use to make bone. Eating enough gelatin can also offset the inflammatory load caused by excessive amounts of methionine, the amino acid found abundantly in muscle meat.

Vitamin D, vitamin A, and vitamin K2: The Third Triumvirate, these three synergistically promote healthy bone metabolism. Both vitamin D and vitamin K2 have been shown to improve osteoporosis, and people often say that vitamin A is bad for bone health, but they actually promote better bones when obtained together. For vitamin D, get sun exposure or supplement to reach a blood level between 30-50 ng/dL. For vitamin A, eat liver once a week or take the aforementioned cod liver oil (which is also a source of vitamin D). For vitamin K2, eat natto, gouda, and goose liver.

Leafy greens: Greens like kale and spinach contains important minerals (calcium and magnesium) and polyphenols for bone health and inflammation.

Small bony fish: Bone-in fish like sardines provide the important pro-bone trio of animal protein, anti-inflammatory omega-3s, and bioavailable calcium.

Also, check the list of pro-bone nutrients, vitamins, and supplements listed in the recent Dear Mark post. Those that increase the healing of broken bones will also fortify otherwise healthy ones.

7. Avoid chronic inflammation

There’s strong evidence (both mechanistic and observational) that inflammation and bone health are linked.

Eating too many omega-6 PUFAs and too few omega-3s can increase inflammation and inhibit the creation of new bone cells.

Being obese imparts a low-grade inflammatory state that impairs bone growth in teen girls and associates with osteoporosis in older adults.

Elevated circulating CRP is consistently associated with osteoporosis.

Finally, resolution of inflammation has been shown to restore the lost osteoblast activity, so be sure to address any aspects of your diet and lifestyle that increase net inflammation.

8. Eat lots of produce

Amid all the hullabaloo regarding the relationships of animal protein, dairy, and other “controversial” foods with osteoporosis, everyone can agree that fruit and vegetable consumption has a positive connection to bone health. Study after study shows that greater intakes of fruit and vegetable (and potassium and magnesium which are markers for produce intake) predict better bone health.

There was even a controlled trial from earlier this year that found a diet consisting of vegetation known to have specific bone-friendly micronutrients and compounds—bok choy, red lettuce, Chinese cabbage, citrus fruits, parsley, sage, rosemary, and thyme—improved bone metabolism biomarkers compared to a control diet and an intervention diet full of regular old vegetation (PDF).

It’s a good idea to focus on phytonutrient-rich produce. Think colorful fruits and vegetables, like purple potatoes, cabbage, and carrots and berries of all kinds. even extra virgin olive oil contains a polyphenol with bone-promoting effects.

Sound like a lot to take in? For the big takeaways, the interventions that provide the most benefit, the things you can tell your mom (or yourself) to start doing and expect actual results without getting bogged down in the details, try the following:

Lift heavy things twice a week. “Heavy” is relative (it just has to be heavy for you, not for Internet lifting board denizens). Even “things” is relative (it could be your own bodyweight, which isn’t an external thing in the normal sense of the word). But “lift” is unequivocal.

Expose your body to strong but manageable impacts. Sprinting will do it. Olympic lifting, box jumps, jump squats, playing sports will do it. But so will simply hopping in place, if that’s what you can manage.

Perform but don’t rely on low-impact exercise. Biking, swimming, and brisk walking are great ways to stay active and get in shape, but they don’t exert enough impact to stimulate bone strengthening.

Obtain enough calcium (600-1000 mg), magnesium (400 mg), and trace minerals. A liter of Gerolsteiner would get you on your way. High quality full-fat dairy and leafy greens round out the rest.

Obtain enough vitamin D, vitamin A, and vitamin K2. Get regular sun exposure or take a vitamin D3 supplement (vitamin D). Eat liver once a week or supplement with cod liver oil (vitamin A). Eat natto and gouda regularly (vitamin K2). To be sure, take a vitamin K2 supplement, since not everyone can stomach natto and I wouldn’t trust my K2 intake entirely to gouda.

Eat a variety of colorful fruits, vegetables, spices, and herbs. These provide important minerals, vitamins, phytonutrients, and antioxidant compounds that can reduce inflammation and improve bone health.

Avoid chronic inflammation.

If poor bone health is present, look into some of the supplements listed.

The longer you wait to enact these changes, the more interventions you’ll have to introduce. It’s easier to keep what you have than get back what you’ve lost.

What about you, folks? How do you address bone health? Since going Primal, has your bone density improved (if you’ve checked)?

March 28, 2016

Dear Mark: Staying Aerobic, Glycogen Depletion, and Sleep-Low for Strength Training?

For today’s edition of Dear Mark, I’m answering three reader questions. First, do anaerobic workouts—sprints, lifting, etc.—interfere with your ability to become a fat-burning, aerobic beast, or can you integrate them? Next, in last week’s post I talked a lot about glycogen depletion in the context of the “sleep-low” carb partitioning. How can we actually achieve this without doing the intense intervals the elite triathletes were doing in the study? And finally, does carb-fasting after strength training also work?

For today’s edition of Dear Mark, I’m answering three reader questions. First, do anaerobic workouts—sprints, lifting, etc.—interfere with your ability to become a fat-burning, aerobic beast, or can you integrate them? Next, in last week’s post I talked a lot about glycogen depletion in the context of the “sleep-low” carb partitioning. How can we actually achieve this without doing the intense intervals the elite triathletes were doing in the study? And finally, does carb-fasting after strength training also work?

Let’s go:

I’ve read Primal Fitness, 21 Day, and now am halfway thru Primal Endurance. You could say I believe in and am an example of the efficacy of your teaching. I’ve been using the 4 days of play, 2 days of LHT, and one day of HIIT as outlined in PF and 21. My confusion comes from the emphasis in Primal Endurance on staying aerobic and how even a short duration of anaerobic can negatively effect body’s ability to function aerobically. I find even when playing Frisbee on a play day I can get my heart rate above my aerobic max after a short sprint, and I definitely get above my max aerobic HR when I do the LHT sessions and HIIT sessions. Im not training for any endurance competitions, just like being really fit so Im thinking the primal endurance model is more focused on those training for super endurance activity but any clarification of the confusion I have re aerobic and anaerobic would be appreciated.

Getting the heart rate up briefly on occasion as you are doing is good and won’t jeopardize your fat-burning pursuits. In the book, we emphasize becoming as efficient as possible at burning fat at the “low end” before you start adding speed if you are seeking the most efficient way to get to racing faster by burning more fat. For that reason, we like picking some workouts where you stay at or below that aerobic zone for as long as possible. So if you are training for a marathon, triathlon or Spartan event, you might put a few more of those dedicated low HR sessions into your routine. But doing harder workouts that rely more on glycogen for energy won’t “ruin” your aerobic base, especially if you’re just a “regular” exerciser looking to get fit, strong, fast, and more attractive. They’ll actually improve your ability to burn fat.

The problems arise when you rely on glycogen all the time and never force your body a chance to rely on fat. So in your case, mixing it up is fine and fun and desirable. I always hammer on this point, and it bears true here: there are no “right” answers here, just choices. In Primal Endurance, we wanted to offer choices that got you to your maximum fat-burning efficiency fastest for those athletes who needed it. People who aren’t hardcore endurance athletes can still learn from and implement the concepts described in the book, but they don’t “have” to follow them to a tee.

“Whatever you do, be sure to really deplete glycogen and wait for 12-16 hours to refill it.”

How do you know when you’ve depleted your glycogen?

Great question. Let’s talk about glycogen depletion.

Glycogen depletion is localized. High rep bicep curls will deplete bicep glycogen. They will not affect glycogen stored in other muscles. Compound movements like squats and deadlifts are better because they’ll deplete multiple sites.

The higher the intensity, the greater the glycogen depletion. Walking depletes very little glycogen. Sprinting depletes the most. Anytime you increase the intensity, you’re increasing the glycogen burn.

Some ideas for glycogen depletion workouts:

Kettlebell complex: 10 swings, 10 clean and presses (5 each arm), 20 reverse lunges (10 each leg), 10 bent over rows (5 each arm). 5 rounds, no rest between movements, minute rest between rounds. You hit pretty much every muscle group. This basic concept can also be done with dumbbells, barbells, and even weight machines.

High rep burpees: Twenty burpees, performed as quickly and cleanly (don’t sacrifice form) as you can. Rest two minutes. Repeat at least 5 times. Burpees are great because they hit arms, chest, legs.

Hill sprints: Run longer sprints with longer rest periods. Throw in some pushups and pullups in between sprints to hit other body parts (because sprinting only depletes the lower body, especially the posterior chain—hamstrings and glutes) if location and available equipment permit. Maybe some bodyweight squats, too, which are pretty quad-dominant.

These 10-minute full body workouts should all work well, too.

One way to tell if you’re depleting glycogen is the difficulty. If a workout is easy, you’re not depleting a ton. If a workout is grueling, you’re depleting it. Strike a balance between hard work, sustainability, and willingness to perform. Short ultra-intense sprints might deplete the most glycogen per second, but how many seconds can you keep it up? 200-meter hill sprints with 5-minute rest periods will blast your lower body glycogen stores, but how willing are you to do that workout on a regular basis?

Another indication of glycogen depletion is if the workout increases glycogen uptake into muscles. If your muscles are taking in more glycogen after a workout, they probably depleted it during the workout. Both sprint and moderate intensity training increase muscle-specific glucose uptake. And strength training definitely increases muscle glucose uptake.

Does this still apply to the more traditional full-body strength workout? I would love to try if so. My carbs have been in the 200-250g range but I’m doing three strength workouts, a sprint workout, and the other days are pretty active playing sports or hiking with my 3 year old. Thanks!

Sure, why not? Full body resistance training and sprinting can certainly deplete glycogen. Maybe not as completely as if you were a triathlete doing long intense intervals every day, but it works. Remember that strength training definitely increases muscle glucose uptake, a strong indicator for prior depletion. And you’re also not eating 6 grams of carbs for every kg of bodyweight like the triathletes in the study were eating, meaning you don’t have as much to deplete. So give it a try. Keep your carb intake constant, just eat them before your workouts rather than after. Try to time it so that you end your carb-free time with a hike or other “low-moderate intensity” activity to really boost fat utilization.

Here’s how it might go:

Eat your carbs.

Sprint or strength train.

Have some protein post-workout, maybe a little whey. No carbs.

Avoid carbs for at least 12 hours. Eat low-carb vegetables, meat, fat. Nothing starchy, nothing sweet.

End your “carb fast” with a hike, walk, or play session. Nothing too strenuous.

Now eat some carbs.

Keep that 200-250 gram carb range going. The implications of the study from last week are that you can eat the same amount of carbs as long as you partition them differently. It’d be cool to see if this works in a standard strength trainee, too. Don’t see why it won’t.

That’s it for today. Any other glycogen-depleting workouts you guys can share?

Thanks for reading, everyone. If any of you have additional tips, input, or questions, leave them down below!

March 27, 2016

Weekend Link Love – Edition 393

PaleoDork is giving away a $100 gift certificate to the Primal Blueprint store. Enter to win here. Ends tomorrow at 11:45 PM, EST.

PaleoDork is giving away a $100 gift certificate to the Primal Blueprint store. Enter to win here. Ends tomorrow at 11:45 PM, EST.

Romy Dolle, author of Fruit Belly, is putting on a small PaleoFX-esque convention in Spreitenbach, Switzerland next month on April 9. Get your tickets to Pure Food Fitness now!

Research of the Week

Lateral squats improve sprint performance.

People with intermittent explosive disorder (more common than bipolar and schizophrenia combined) are more likely to carry a toxoplasmosis infection.

The more readily available a food, the more you’re driven to consume it.

New Primal Blueprint Podcasts

Episode 112: Todd White, Dry Farm Wines: I chat with my friend Todd White, founder of the revolutionary new wine company I featured in the blog earlier this week. You’ll learn why wine causes early morning awakenings, how much alcohol is too much, what additives and chemicals conventional wine producers are adding to their bottles, why natural wines are different (and better), and much much more.

Each week, select Mark’s Daily Apple blog posts are prepared as Primal Blueprint Podcasts. Need to catch up on reading, but don’t have the time? Prefer to listen to articles while on the go? Check out the new blog post podcasts below, and subscribe to the Primal Blueprint Podcast here so you never miss an episode.

Why Are Some Wines More Primal-Approved Than Others?

How to Handle Constructive Criticism as a Primal Advocate

Interesting Blog Posts

What makes mashed potatoes with butter more satiating than potatoes fried in canola oil?

What’s wrong with Science-Based Medicine (the blog)?

Media, Schmedia

Accidental deadlift world records are the best.

Time covers the benefits of skipping showers.

More fasting coverage, this time in the NY Post.

Everything Else

Maria Emmerich just released an excellent new ketogenic cookbook. If you thought keto dieting was boring and monotonous, think again.

Kids gone wild (SFW).

Prairie dogs practice infanticide and manage to look really cute doing it.

Early Irish were scraping bear patellas during the Mesolithic almost 13,000 years ago. This pushes human presence in Ireland back about 2500 years.

Prozac probably isn’t very safe (or effective) for depressed children.

Bacteria that degrade plastic.

Istanbul farmers are fighting to keep their 1500 year-old urban gardens going.

Simplifying childhood isn’t just easier for everyone, it may produce healthier and happier children with fewer mental health issues.

Recipe Corner

The Nordic Food Lab is doing some incredible things with edible insects. Its latest is a series of insect garums—fermented insect sauces in the style of fish sauce.

Abel James’ take on the Big Ass Salad is legit.

Time Capsule

One year ago (Mar 30 – Apr 5)

25 Ways to Improve Your Insulin Sensitivity – How to use insulin more efficiently.

Self-Control: The Ultimate Exercise of Freedom – Discipline begets freedom.

Comment of the Week

Better get several cases. You know, to make sure you get enough data points for statistical significance…

– I always appreciate your rigor, Paleo Bon Rurgundy.

March 26, 2016

Sardine Butter and Parmigiano-Reggiano Sesame Crisps

Sardine Butter. Does the combination of these two words have you salivating or grimacing? Canned sardines are a delicious, nutritious fish, but they aren’t everyone’s favorite. The flavor can be a little, well, fishy. But there are a lot of omega-3s and other nutrients packed into those small, oily little fish, so finding a way to love ‘em is a worthwhile endeavor.

Sardine Butter. Does the combination of these two words have you salivating or grimacing? Canned sardines are a delicious, nutritious fish, but they aren’t everyone’s favorite. The flavor can be a little, well, fishy. But there are a lot of omega-3s and other nutrients packed into those small, oily little fish, so finding a way to love ‘em is a worthwhile endeavor.

Butter, on the other hand…who doesn’t love butter? Mashing butter and canned sardines together with lemon and cayenne makes a simple but stunning spread. Sardine butter has a more assertive, less delicate flavor than anchovy butter. But sardine butter is much less “fishy” than sardines straight out of the can (if that’s a plus for your taste buds).

In recipes like this, with so few ingredients, quality matters. Use your favorite salted butter, hopefully one that’s pastured or cultured. Grab a few cans of sardines from the grocery store, taste-testing to find you favorite. Boneless sardines give the butter a smoother texture, but if you don’t mind a little crunchiness (and want the calcium) then go ahead and use bone-in. Whether they’re smoked or un-smoked, packed in water or olive oil, is your choice.

Sardine butter can be spread on your favorite Primal cracker, or on the Parmigiano-Reggiano & sesame crisps included in the recipe below. Sardine butter is fantastic spread on raw, crunchy veggies like radishes or dolloped onto warm roasted vegetables.

Servings: Approximately 1 cup sardine butter

Time in the Kitchen: 10 minutes

Ingredients:

1 can sardines, drained of water or oil (4 ounces/120 g)

6 ounces salted butter, room temperature (170 g)

Juice of 1/2 a small lemon

1/4 teaspoon cayenne (1.2 ml)

Instructions:

Depending on how much you like canned sardines, you can use the whole can or just 1 or 2 fillets for this recipe.

In a bowl, use a fork to mash the sardines and butter together. Add the lemon juice and cayenne and mash until blended in.

Pack the butter into a small dish or scoop it onto parchment paper and roll it into a log that can be sliced. The butter can be served immediately or refrigerated until firm.

Parmigiano-Reggiano Sesame Crisps

Ingredients:

3 ounces Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese (85 g)

A few grinds black pepper

2 tablespoons sesame seeds (30 ml)

Instructions:

Preheat oven to 350°F/176°C.

Line a sheet pan with parchment paper.

Grind half the cheese with the side of the box grater that grates shreds of cheese, and half the cheese with the side of a box grater that grates cheese very finely.

Combine both piles of cheese in a bowl with black pepper.

Drop rounded tablespoons of the cheese on the baking sheet. Sprinkle sesame seeds on each pile.

Bake 6 to 7 minutes until bubbling and golden.

Let cool, then remove from pan with a spatula.

Not Sure What to Eat? Get the Primal Blueprint Meal Plan for Shopping Lists and Recipes Delivered Directly to Your Inbox Each Week. Now Available as an App!

March 25, 2016

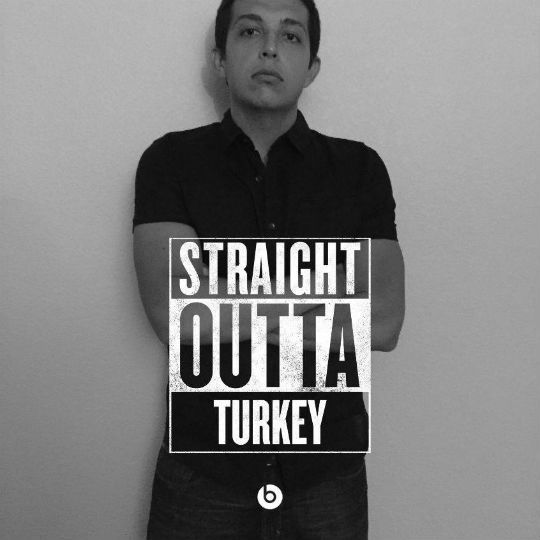

How I Lost 160 Pounds and Reclaimed My Brain by Going Primal

It’s Friday, everyone! And that means another Primal Blueprint Real Life Story from a Mark’s Daily Apple reader. If you have your own success story and would like to share it with me and the Mark’s Daily Apple community please contact me here. I’ll continue to publish these each Friday as long as they keep coming in. Thank you for reading!

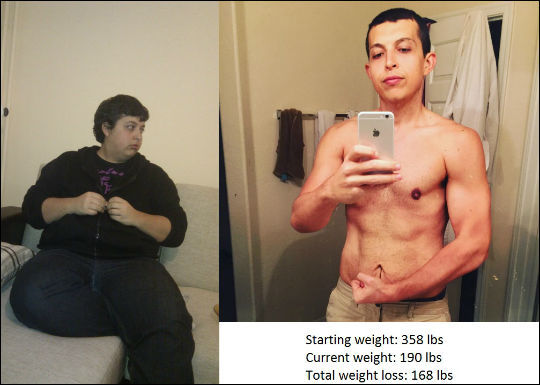

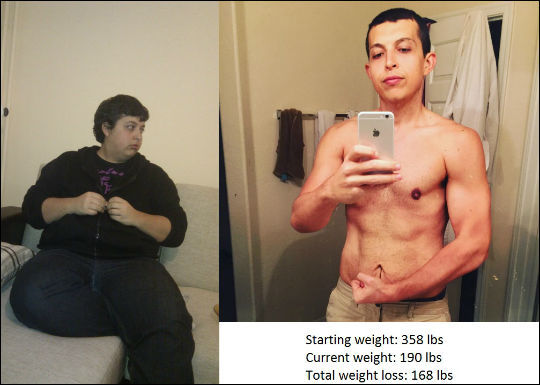

In June of 2011, I received my Bachelor of Science degree in electrical engineering at Bilkent University in Turkey, with a GPA of 3.28/4.00 (you will see why I shared my GPA later on.) At that time my weight was 358 lbs. Then I followed up with my Master of Science in Electrical Engineering at Arizona State University. (I am currently doing my PhD in the same program with a MS degree already in hand.) When I realized that I was coming over to a completely different country (even continent), I made up my mind on becoming healthier, taking control over my life and losing the extra weight I had been carrying on for years.

In June of 2011, I received my Bachelor of Science degree in electrical engineering at Bilkent University in Turkey, with a GPA of 3.28/4.00 (you will see why I shared my GPA later on.) At that time my weight was 358 lbs. Then I followed up with my Master of Science in Electrical Engineering at Arizona State University. (I am currently doing my PhD in the same program with a MS degree already in hand.) When I realized that I was coming over to a completely different country (even continent), I made up my mind on becoming healthier, taking control over my life and losing the extra weight I had been carrying on for years.

So at first, I started cutting calories, eating very little and exercising regularly. I’m not going to lie: I was losing weight. I had lost about 60 lbs that way in one year. However, I was constantly hungry, lethargic and foggy. After the first semester in my Master’s program, my term GPA was 2.89/4.00. So unless I did something about my health, I was going to fail the graduate program, be kicked out of school and forced to return to my home country. (When you have a GPA of under 3.00/4.00 after one year, you are done.)

So at first, I started cutting calories, eating very little and exercising regularly. I’m not going to lie: I was losing weight. I had lost about 60 lbs that way in one year. However, I was constantly hungry, lethargic and foggy. After the first semester in my Master’s program, my term GPA was 2.89/4.00. So unless I did something about my health, I was going to fail the graduate program, be kicked out of school and forced to return to my home country. (When you have a GPA of under 3.00/4.00 after one year, you are done.)

Don’t get me wrong. I love my country, but I wanted to build my future here in the USA. So I stopped the calorie counting and exercising for one semester to save my education. I got a 3.78/4.00 (which increased my overall GPA to 3.33/4.00) in the next semester and secured my spot in the university for another year. But with that sacrifice, I gained some of the weight I had lost and was almost close to where I started. On the other hand, I was able to pass my classes with high grades and at the end I actually got my Master’s degree. As soon as that was done, I was admitted to the PhD program, but there was one problem: I was still unhealthy and obese. I knew there was a way to lose all the weight, get high grades and make contributions to the engineering world at the same time. So as any other engineering student would do, I started taking a deeper dive into the research in order to find out how I could get out of the unhealthy habits of dieting to lose weight and actually excel in my study at the same time.

Enter Primal living. I found out about your blog, which led me to reading peer reviewed publications and amazing books. I wanted to give it a shot because it all made sense. The picture I had understood back then was simple: If I eat what nature provides and keep my body moving/playing, everything will be in order. And like our ancestors, I will strive. It was simple as that, at first at least (after a while, I dug into more research and learned about human biochemistry and everything else, all thanks to you.) So I started eating more fat from good sources. I fell in love with avocados, which I never even tasted back in Turkey. I cut down on my carb intake. I started eating my carbs at dinner on my hard training days. I started enjoying grassfed/pasture-raised healthy ground beef and turkey, which I tried to stay away from for years. I started eating wild caught seafood like salmon, tuna, halibut, cod, scallops and shrimp. Then I finally tried wild caught sardines. OH MY GOD, I love eating sardines now.

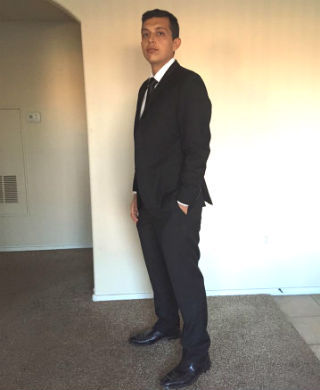

Two years into my PhD program, I have a GPA of 4.00. It’s actually more with all the A+’s I got, but overall GPA does not go above 4.00.  What is more is that I now weigh 190 lbs with some of my abs showing up, which you can see in the attached photo. I feel more energetic and more focused than I have ever felt in my entire life. I currently live in Phoenix, AZ where I get my sunlight every day, sleep eight hours every night and eat what nature supplies from our local farmers.

What is more is that I now weigh 190 lbs with some of my abs showing up, which you can see in the attached photo. I feel more energetic and more focused than I have ever felt in my entire life. I currently live in Phoenix, AZ where I get my sunlight every day, sleep eight hours every night and eat what nature supplies from our local farmers.

Let me explain a little bit more about what I did after finding out about Mark’s Daily Apple. After starting to read more and more on MDA, the information resonated with me. I began to understand what I should eat, how I should move, and how and when I should sleep. For example, some of the things I started implementing were: getting eight hours of sleep at night and cutting out the awful-tasting bread slices and “healthy” fruit juices (those sugar filled evil drinks) in my breakfast. For exercise, I stopped running on the treadmill like a hamster, and started lifting some weights like Grok, sprinting every once in a while, and my favorite: just moving around and walking in nature.

In Phoenix, there are tons of hiking trails and the beautiful sun is out almost 11 months of the whole year. Hence I started hiking more often, discovering new trails and I even started making new friends who were hiking the same trails. One thing I want to share here is that after walking around in nature, I realized that my sleep quality became better. After reading a little bit more about this, I realized that this was thanks to being close to the beautiful vibration of earth and getting the whole spectrum of the sunlight. Here is an example of a weekly workout:

In Phoenix, there are tons of hiking trails and the beautiful sun is out almost 11 months of the whole year. Hence I started hiking more often, discovering new trails and I even started making new friends who were hiking the same trails. One thing I want to share here is that after walking around in nature, I realized that my sleep quality became better. After reading a little bit more about this, I realized that this was thanks to being close to the beautiful vibration of earth and getting the whole spectrum of the sunlight. Here is an example of a weekly workout:

2 days of heavy lifting: 5 reps of squats, deadlifts, over-head press, bent rows

1 day of sprinting or walking on a treadmill

1 day of playing basketball with my friends or hiking

And the rest of the days, I just simply walked or tried to stay active. It was that simple. I was not locking myself inside of a gym for hours and hours. I was just simply applying the good information put out by Mark.

So, thank you so much for putting this outstanding, incredible information out there. I’m trying my best to pay it forward by sharing my story and explaining to other people how a lifestyle change can impact our lives.

Thank you,

Mehmet Bugra Balaban

How I lost 160 Pounds and Reclaimed My Brain by Going Primal

It’s Friday, everyone! And that means another Primal Blueprint Real Life Story from a Mark’s Daily Apple reader. If you have your own success story and would like to share it with me and the Mark’s Daily Apple community please contact me here. I’ll continue to publish these each Friday as long as they keep coming in. Thank you for reading!

In June of 2011, I received my Bachelor of Science degree in electrical engineering at Bilkent University in Turkey, with a GPA of 3.28/4.00 (you will see why I shared my GPA later on.) At that time my weight was 358 lbs. Then I followed up with my Master of Science in Electrical Engineering at Arizona State University. (I am currently doing my PhD in the same program with a MS degree already in hand.) When I realized that I was coming over to a completely different country (even continent), I made up my mind on becoming healthier, taking control over my life and losing the extra weight I had been carrying on for years.

In June of 2011, I received my Bachelor of Science degree in electrical engineering at Bilkent University in Turkey, with a GPA of 3.28/4.00 (you will see why I shared my GPA later on.) At that time my weight was 358 lbs. Then I followed up with my Master of Science in Electrical Engineering at Arizona State University. (I am currently doing my PhD in the same program with a MS degree already in hand.) When I realized that I was coming over to a completely different country (even continent), I made up my mind on becoming healthier, taking control over my life and losing the extra weight I had been carrying on for years.

So at first, I started cutting calories, eating very little and exercising regularly. I’m not going to lie: I was losing weight. I had lost about 60 lbs that way in one year. However, I was constantly hungry, lethargic and foggy. After the first semester in my Master’s program, my term GPA was 2.89/4.00. So unless I did something about my health, I was going to fail the graduate program, be kicked out of school and forced to return to my home country. (When you have a GPA of under 3.00/4.00 after one year, you are done.)

So at first, I started cutting calories, eating very little and exercising regularly. I’m not going to lie: I was losing weight. I had lost about 60 lbs that way in one year. However, I was constantly hungry, lethargic and foggy. After the first semester in my Master’s program, my term GPA was 2.89/4.00. So unless I did something about my health, I was going to fail the graduate program, be kicked out of school and forced to return to my home country. (When you have a GPA of under 3.00/4.00 after one year, you are done.)

Don’t get me wrong. I love my country, but I wanted to build my future here in the USA. So I stopped the calorie counting and exercising for one semester to save my education. I got a 3.78/4.00 (which increased my overall GPA to 3.33/4.00) in the next semester and secured my spot in the university for another year. But with that sacrifice, I gained some of the weight I had lost and was almost close to where I started. On the other hand, I was able to pass my classes with high grades and at the end I actually got my Master’s degree. As soon as that was done, I was admitted to the PhD program, but there was one problem: I was still unhealthy and obese. I knew there was a way to lose all the weight, get high grades and make contributions to the engineering world at the same time. So as any other engineering student would do, I started taking a deeper dive into the research in order to find out how I could get out of the unhealthy habits of dieting to lose weight and actually excel in my study at the same time.

Enter Primal living. I found out about your blog, which led me to reading peer reviewed publications and amazing books. I wanted to give it a shot because it all made sense. The picture I had understood back then was simple: If I eat what nature provides and keep my body moving/playing, everything will be in order. And like our ancestors, I will strive. It was simple as that, at first at least (after a while, I dug into more research and learned about human biochemistry and everything else, all thanks to you.) So I started eating more fat from good sources. I fell in love with avocados, which I never even tasted back in Turkey. I cut down on my carb intake. I started eating my carbs at dinner on my hard training days. I started enjoying grassfed/pasture-raised healthy ground beef and turkey, which I tried to stay away from for years. I started eating wild caught seafood like salmon, tuna, halibut, cod, scallops and shrimp. Then I finally tried wild caught sardines. OH MY GOD, I love eating sardines now.

Two years into my PhD program, I have a GPA of 4.00. It’s actually more with all the A+’s I got, but overall GPA does not go above 4.00.  What is more is that I now weigh 190 lbs with some of my abs showing up, which you can see in the attached photo. I feel more energetic and more focused than I have ever felt in my entire life. I currently live in Phoenix, AZ where I get my sunlight every day, sleep eight hours every night and eat what nature supplies from our local farmers.

What is more is that I now weigh 190 lbs with some of my abs showing up, which you can see in the attached photo. I feel more energetic and more focused than I have ever felt in my entire life. I currently live in Phoenix, AZ where I get my sunlight every day, sleep eight hours every night and eat what nature supplies from our local farmers.

Let me explain a little bit more about what I did after finding out about Mark’s Daily Apple. After starting to read more and more on MDA, the information resonated with me. I began to understand what I should eat, how I should move, and how and when I should sleep. For example, some of the things I started implementing were: getting eight hours of sleep at night and cutting out the awful-tasting bread slices and “healthy” fruit juices (those sugar filled evil drinks) in my breakfast. For exercise, I stopped running on the treadmill like a hamster, and started lifting some weights like Grok, sprinting every once in a while, and my favorite: just moving around and walking in nature.

In Phoenix, there are tons of hiking trails and the beautiful sun is out almost 11 months of the whole year. Hence I started hiking more often, discovering new trails and I even started making new friends who were hiking the same trails. One thing I want to share here is that after walking around in nature, I realized that my sleep quality became better. After reading a little bit more about this, I realized that this was thanks to being close to the beautiful vibration of earth and getting the whole spectrum of the sunlight. Here is an example of a weekly workout:

In Phoenix, there are tons of hiking trails and the beautiful sun is out almost 11 months of the whole year. Hence I started hiking more often, discovering new trails and I even started making new friends who were hiking the same trails. One thing I want to share here is that after walking around in nature, I realized that my sleep quality became better. After reading a little bit more about this, I realized that this was thanks to being close to the beautiful vibration of earth and getting the whole spectrum of the sunlight. Here is an example of a weekly workout:

2 days of heavy lifting: 5 reps of squats, deadlifts, over-head press, bent rows

1 day of sprinting or walking on a treadmill

1 day of playing basketball with my friends or hiking

And the rest of the days, I just simply walked or tried to stay active. It was that simple. I was not locking myself inside of a gym for hours and hours. I was just simply applying the good information put out by Mark.

So, thank you so much for putting this outstanding, incredible information out there. I’m trying my best to pay it forward by sharing my story and explaining to other people how a lifestyle change can impact our lives.

Thank you,

Mehmet Bugra Balaban

Like This Blog Post? Subscribe to the Mark's Daily Apple Newsletter and Get 10 eBooks and More Delivered to Your Inbox for FREE

March 24, 2016

How a Primal Lifestyle Can Help You Find Your Passion

I saw someone wearing a t-shirt the other day that read “Do More of What You Love.” It was a simple message but a welcome shift from the deluge of difficult news and negative media we’re often met with. I wasn’t in a hurry that day and let my mind wander with it while I waited for a friend. The fact is, over the years I’ve managed to revamp my life in such a way that I am indeed doing more of what I love. It’s taken time, but I’ve combined what I should do to take care of myself with what I enjoy doing. Trading hours of training each day for beach sprints, surfing and Ultimate has been a part of that. But so has taking more time to be in community and to write. I’m in a profession now that I find fulfilling, and I pursue a whole range of hobbies that bring me a good share of joy in addition to well-being. Going Primal rebuilt my health, but it’s also transformed my life and helped me stumble into passions I didn’t realize I had. Beyond being in the business itself, however, I think there’s truly something to just living the Primal way that’s conducive to discovering what you love.

I saw someone wearing a t-shirt the other day that read “Do More of What You Love.” It was a simple message but a welcome shift from the deluge of difficult news and negative media we’re often met with. I wasn’t in a hurry that day and let my mind wander with it while I waited for a friend. The fact is, over the years I’ve managed to revamp my life in such a way that I am indeed doing more of what I love. It’s taken time, but I’ve combined what I should do to take care of myself with what I enjoy doing. Trading hours of training each day for beach sprints, surfing and Ultimate has been a part of that. But so has taking more time to be in community and to write. I’m in a profession now that I find fulfilling, and I pursue a whole range of hobbies that bring me a good share of joy in addition to well-being. Going Primal rebuilt my health, but it’s also transformed my life and helped me stumble into passions I didn’t realize I had. Beyond being in the business itself, however, I think there’s truly something to just living the Primal way that’s conducive to discovering what you love.

There’s something ironic to all this of course. Grok and his kin didn’t have all the opportunities we do—not in the incredible span of possibility available to us anyway. The priority was survival, and a lot of time and energy were invested in that most basic of pursuits.

And yet…

Grok wasn’t funneled into a minute specialization from an early age or expected to work a 40-80 hour work week on top of a long commute. The guy had a fair amount of leisure and choices in the very rough and rudimentary scheme of things.

On the other hand, many people today lead lives of flatness or even despair in which they take paths dictated by cultural or familial expectation—or by the pursuit of money over passion. They go whole decades of life never asking what they’d rather be doing, and those frustrated inclinations end up coming out sideways in a midlife crisis or just a subtle resentment that smolders each day.

Some might scoff and mutter, “first world problems,” but I’d argue it’s a natural human instinct to want more in terms of actualization. Human evolution didn’t stagnate after all. Our ancestors were curious and ambitious, and we should be grateful for it.