Mark Sisson's Blog, page 224

April 29, 2016

Family Loses 335 Pounds: A Piano Family Update

It’s Friday, everyone! And that means another Primal Blueprint Real Life Story from a Mark’s Daily Apple reader. If you have your own success story and would like to share it with me and the Mark’s Daily Apple community please contact me here. I’ll continue to publish these each Friday as long as they keep coming in. Thank you for reading!

My name is Jennifer Piano, wife of David Piano, and our family took on the Primal lifestyle about two years ago. We started shortly after finding out we were pregnant with our last child.

My name is Jennifer Piano, wife of David Piano, and our family took on the Primal lifestyle about two years ago. We started shortly after finding out we were pregnant with our last child.

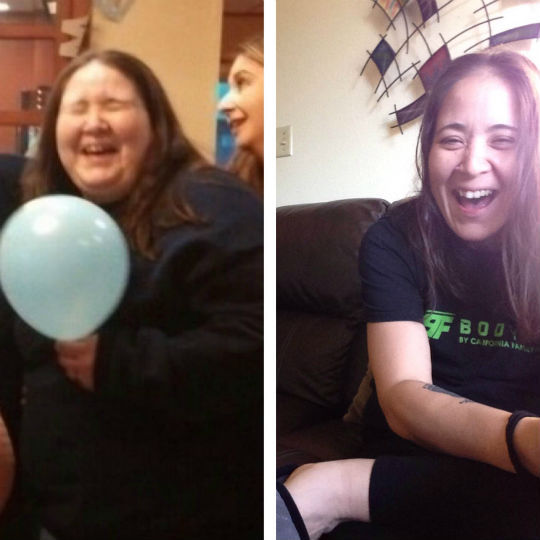

Before taking on the Paleo lifestyle I had suffered from depression for many, many years and was addicted to crystal meth for six years. After being saved from the addiction of meth, I replaced that addiction with food, slowly eating myself to a enormous 310+ pounds.

I was diagnosed with severe rheumatoid arthritis, high blood pressure, and was borderline diabetic. At this point I knew something had to change if I wanted to live a long healthy life for myself and my family. It wasn’t until then that my husband’s cousin introduced him to Mark’s Daily Apple and the Paleo lifestyle.

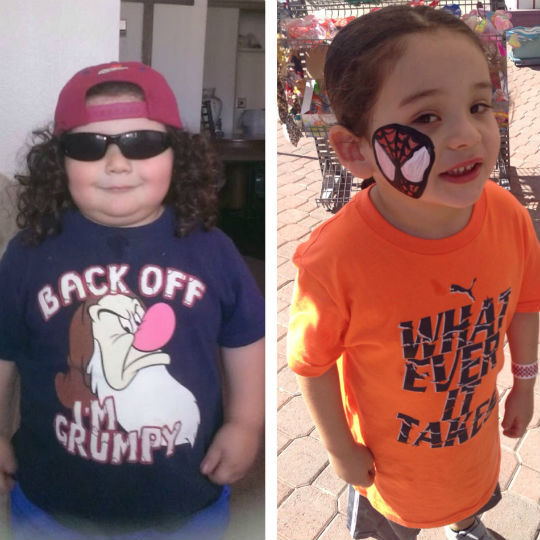

My son Matthias, who at the time was only two years old, weighed in at 71 pounds. He didn’t have the energy to play and always had an upper respiratory infection. Since changing our eating habits, he too has lost an incredible amount of weight. At almost five years old, he now weighs 54 pounds and has an enormous amount of energy.

As a family, we were able to lose roughly 335 pounds. I lost 180 pounds and just recently reached my weight goal of 130 pounds. Went from a size 24 to now a size 4. Now all that’s left to do is tone, tone and more toning. I thank you for your help and for your website!! And I know that with your website you will inspire others to reach their weight loss goals! Thank you for all that you do!!

Jennifer

April 28, 2016

Why Weight Loss Doesn’t Promise Happiness

There are any number of amazing reasons to lose weight that will offer incredible benefits in the long- and short-term. You’ll be in better overall health. It’s very probable that you’ll live longer and have more vitality in those years—particularly if getting in shape was part of your weight loss strategy. You’ll enjoy more energy for the people and activities you love. You may have more or preferable clothing choices. You’ll have a better chance of kicking many prescription drugs to the curb (and save a little dough in doing so). To boot, you’re likely to experience less chronic pain and a better night’s sleep, etc., etc. All that said, let’s be clear on something: weight loss isn’t a guaranteed stimulus to your personal happiness. Here’s why.

There are any number of amazing reasons to lose weight that will offer incredible benefits in the long- and short-term. You’ll be in better overall health. It’s very probable that you’ll live longer and have more vitality in those years—particularly if getting in shape was part of your weight loss strategy. You’ll enjoy more energy for the people and activities you love. You may have more or preferable clothing choices. You’ll have a better chance of kicking many prescription drugs to the curb (and save a little dough in doing so). To boot, you’re likely to experience less chronic pain and a better night’s sleep, etc., etc. All that said, let’s be clear on something: weight loss isn’t a guaranteed stimulus to your personal happiness. Here’s why.

It can seem like an affront to all we hope. “If I’m at a healthier weight, that means I’m healthier, which of course means I’ll be happy!” The media and commercial images tell us so. Every check-out kiosk is lined with celebrity tell-alls sharing the boon of weight loss to the happiness of said personalities and their families. Television and online commercials tell the same stories. A spokesperson loses weight and thereby has the life he/she always dreamed of.

I’ll be the first to admit that for some people it really does work this way—but there’s more to those situations than people think. Weight loss and the resulting health enhancements can top off the natural contentment and confidence some people for the most part already have. Alternatively, it becomes a catalyst for psychological work that matches the same vigor as their physical transformation.

For many people, however, neither of these is the case, and therein lies the disappointment.

A University College of London study followed nearly 2000 people who received instruction for improving health and managing weight. At end of 4 years, 71% remained the same weight, 15% had gained at least 5% body weight and 14% had lost at least 5% body weight. You’d imagine that the 14% group would be the happiest of the bunch, but not so. In fact, they were twice as likely to be depressed as those in the other groups. Even when the study team accounted for health conditions and key demographic and psychological (e.g. bereavement) variables, the weight loss group still fared the worst in terms of personal happiness and overall well-being.

It’s true that other research findings don’t necessarily concur, but they complexify the question. In one study, obese subjects who lost significant weight (again, more than 5% of body weight) reported better mood along with sleep. However, temporary improved mood doesn’t always correlate with overall happiness.

Another study brings to bear additional considerations. The National Weight Control Registry enrolls participants who have maintained a 30+lbs weight loss for at least a year and defines “clusters” of subjects based on personal history, employed strategies and common attitudes. An analysis project of 2,228 enrollees showed those in the cluster that struggled most with ongoing weight maintenance and used the most outside resources (e.g. commercial weight loss programs, health care providers) reported significant issues with stress management and demonstrated higher depression rates. (PDF)

This is, of course, no surprise, but it underscores the phenomenon of weight “cycling” and highlights the issue (as well as quality) of outer voices in a person’s weight loss experience versus inner motivation. Weight lost doesn’t always mean loss maintained—or a struggle eased. Nor does it suggest a sustainable psychological underpinning for healthy and happy living.

In fact, the opposite scenario might be the more consistently true. University of Adelaide researchers designed a four-week “positivity” pilot study that promoted self-esteem, gratitude and general happiness rather than weight loss. Despite the lack of focus on physical health, half of participants actually lost weight during the study, and three-quarters of those shed additional pounds during the three months following the program.

In my observation over decades of training and coaching people, genuine (long-term) health change—regardless of what it is but maybe especially if it involves the commitment of substantial weight loss—requires a solid foundation of self-efficacy and self-respect. If that’s lacking, no number of pounds lost will ever fill in that gap.

In fact, weight loss can impose unexpected challenges. We might feel more “on display” for public comment (regardless of how positive). We might feel exposed and saddened or perplexed as to why we’re somehow worth more attention or accolades now. We might feel like all of our expanded “worth” is suddenly tenuous and vulnerable.

Many people, particularly those who lose considerable weight relatively quickly, don’t know how to process the incongruity between the image they’ve had of themselves for so long and what they now see in the mirror. I’ve heard people call it an out-of body experience and even the reason for an almost deliberate weight regain.

The fact is, we all come to tell or believe stories about ourselves over time. Maybe it’s been over the course of our entire lifetime that we’ve seen ourselves one way, or maybe it’s something we’ve “settled into” over the last several years, but we come to a set point of physical appearance/activity level, social roles and personal perception. When one changes, we can get uncomfortable even if we and others believe our changes are for the better.

Likewise, other issues in our lives—whether it’s an unhealthy job situation or a floundering relationship or some other source of discontent or anxiety—won’t be fixed just because our outward appearance changes. Even the uptick in energy doesn’t automatically upgrade our outer circumstances.

Because the pounds only mean so much. Even in terms of health, fitness says more about mortality than weight does, and in terms of life happiness, our current weight (unless it’s debilitating us each day) is one of many inputs we process in a day.

Sure, we invest in our well-being every time we eat a good Primal meal or fit in a brisk walk over the lunch hour, but we do the same when we take 20 minutes to meditate in the morning, enjoy time with a good friend, or take in a gorgeous sunset.

There’s a reason I consider the Primal Blueprint an awesome approach for weight loss, but not a weight loss program per se. The Primal Blueprint is about living better, healthier and happier—right now whatever your weight today (or age, health condition, fitness level, etc.). It’s literally about cultivating the good life from all essential angles. The Primal mind doesn’t measure joy in pounds, but in experiences, connection, adventure, flow, self-actualization, creative endeavor and exploration, nourishment, and belonging.

It’s little surprise when we reset our lives toward these priorities and offer ourselves the sustenance that fuels us best that we find a source of energy and motivation to live well in our bodies and happier in ourselves.

Thanks for reading today, everyone. Offer your comments on the weight loss-happiness connection/disconnect, and have a good end to your week.

Like This Blog Post? Subscribe to the Mark's Daily Apple Newsletter and Get 10 eBooks and More Delivered to Your Inbox for FREE

April 27, 2016

10 Common Primal Mistakes You Might Be Making

Most of us go Primal to solve problems created by Conventional Wisdom. The importance of whole grains and daily cardio, the dangers of dietary fat and animal protein, the primacy of carbohydrates for “energy,”—these untruths are promulgated so widely and fail so conclusively that you can’t help but look to the people saying the opposite for direction. That’s where we come in. Most of us go Primal to solve problems created by conventional dietary and lifestyle recommendations. Often these solutions involve doing the opposite of what the authorities are telling us. For the most part, it works.

Most of us go Primal to solve problems created by Conventional Wisdom. The importance of whole grains and daily cardio, the dangers of dietary fat and animal protein, the primacy of carbohydrates for “energy,”—these untruths are promulgated so widely and fail so conclusively that you can’t help but look to the people saying the opposite for direction. That’s where we come in. Most of us go Primal to solve problems created by conventional dietary and lifestyle recommendations. Often these solutions involve doing the opposite of what the authorities are telling us. For the most part, it works.

Sometimes eschewing conventional advice goes too far, though. Sometimes we make serious blunders in our pursuit of Primal perfection.

1. Bacon gorging

Bacon is the forbidden food. It beguiles vegans and tempts die-hard low-fat statin-munchers. So when you learn that bacon won’t kill you, your bacon intake tends to climb. After all, it’s delicious. No one disputes that. But that doesn’t mean you should eat bacon for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. That doesn’t mean bacon should be your primary protein source. You don’t need to gorge on it.

These days, I treat bacon more like a condiment. Chop it up and sprinkle it on salads. Sauté it with Brussels sprouts. Toss it in with roasted sweet potatoes and apples. And yes, I love a good slab of it with some eggs, but not all the time. Don’t be like the college freshman getting drunk at 10 AM in his dorm because his parents aren’t there to stop him.

2. Fat bombs

When you realize that dietary fat can be a force for good—improving nutrient absorption, increasing satiety, upregulating fat metabolism and fat adaptation—and excess refined carbs a force for fat gain, you increase the former and lower the latter. But realize that otherwise healthy fats like butter, coconut oil, olive oil and avocado oil are still refined foods. They’re removed from the source. They’re concentrated. And they should probably not comprise the majority of your calories. Now, these Primal isolated fats are far more nutrient dense than the isolated PUFA-rich fats we avoid (your corn oils, your soybean oils, your canolas) but they can’t compare to fatty whole foods like eggs, ribeyes, avocados, nuts, or seeds. Get most of your fat through foods like avocados, nuts, meat, fish. Reserve fat for cooking. You can still eat a high-fat diet without relying on a quarter cup of coconut oil.

3. Paleo treats

I like a good Primal-approved treat—when the situation calls for one. Almond flour, coconut flour, and other gluten-free nut-based flours can be useful and versatile allies when these situations arise, but as a regular staple food? Eating Primal is about more than just the ingredients. We’re trying to change our relationship to food, not replace the junk wholesale with slightly healthier junk. That’s the province of the gluten-free dieter swapping out Oreos for Oreos made from rice flour and wondering why they gained all that weight.

Are you eating a handful of almonds sliced over yogurt with raw honey? Or are you pulverizing several hundred almonds into flour to make into chocolate cupcakes sweetened with raw honey? Same ingredients, different intent, different outcome. At the end of a day an almond flour pancake is still a pancake and a coconut flour cupcake is still a cupcake.

4. Too much chocolate

[Dodges pitchfork.]

Dark chocolate is absolutely a healthy food. Dozens of studies support it for heart health, mental function, and anti-inflammatory activity. And once you hit the 85% cacao and up range, you’re getting a nice dose of prebiotic fiber, cacao polyphenols, healthy cocoa fat with moderate amounts of sugar. I got nothing against a nice piece of quality dark chocolate. Eat it several times a week, sometimes more.

It’s still candy, though

Explore other avenues for cocoa ingestion. Look into cocoa powders. Make hot chocolate (use coconut milk if you prefer). Incorporate cocoa into your cooking (Oaxacan mole sauce, anyone?). Try unsweetened full-cacao baking chocolate. The sugar is just a way to get more people to eat what is essentially a bitter, initially unpalatable bean. If you can use unsweetened cocoa and control your own desired level of sweetness—or better yet, get used to unsweetened cocoa—you won’t be missing any of the benefits.

5. Too much sun

The dermatologists aren’t all wrong. The sun is a powerful force. With the right exposure, it’s a force for good, reducing the risk of many cancers, improving cardiovascular health, building stronger bones, promoting proper sex hormone function, building happiness, and leaving your skin glowing. But with too much exposure, or exposure at the wrong times, all those hysterical warnings about the sun and skin cancer can actually come true. You don’t want to get burned. You don’t want your skin peeling. You don’t want irregular moles and spots appearing and shifting on your skin. They’ve put millions of people at risk with their zero-tolerance stance on sun exposure, but too much sun can actually be dangerous.

Beef jerky’s awesome. Skin jerky? Not so much. Make sure you’re doing all the right things before you start laying your naked body out in the sun.

6. Avoiding all cardio

Chronic cardio is bad for most people. It’s boring. It sucks the life out of you. It hurts your joints and relationships. And it’s not even very good at reducing body fat and improving body composition. You can get many of the same benefits and a ton of new ones in a time-efficient manner by increasing the intensity and reducing the volume of your workouts. If you aren’t getting paid to do it, don’t do it. That’s settled.

However, a jog around the block isn’t going to kill you. Not all cardio is chronic. Chronic cardio describes the moderate-high intensity, high-volume training people think they have to do to “get fit.” A nice easy jog is fine. A long hike is great. The occasional race-pace longer run is helpful.

Maybe it’s just running a mile every once in awhile. But you don’t have to go hard all the time. There are other worthwhile exercise modalities besides strength training and sprinting.

7. Going down every rabbit hole

On this blog, I discuss a lot of concepts. I’m a curious person and I have a large readership, so whenever I come across an interesting new idea or think of a new approach to an old problem, I share it here.

You don’t have to try everything you read about. You don’t have to go into ketosis, fast, do carb refeeds, try every single permutation of squat and deadlift, sprint uphill/downhill/on a bike/in a pool, hike barefoot, and try the potato diet. These are all just options, choices to be made. I provide information, offer my interpretation, and make suggestions. I don’t expect everyone to do everything. That’s impossible. That’s a recipe for added stress and certain failure.

8. Romanticization of Grok

Some things about our modern existence are screwy and ridiculous, and when we spend our days sitting down, completely isolated from nature, from other humans (in the flesh), from edible plants and animals in their original packaging (absent some fur, perhaps), problems arise. You can’t expect that ignoring the reality of the environmental inputs that shaped our genome can lead to anything but poor health and happiness. Finding modern corollaries that create some of those same environmental inputs really seems to help solve most of our health and lifestyle problems. “Grok” is a helpful frame of reference.

But you don’t need to wear a loin cloth. You don’t need to leave the city and build a home in the forest using primitive skills (that’d be pretty awesome as a summer home, though!).

9. Eschewing modern medicine

Doctors, by and large, want to help you. I would take their lifestyle and diet recommendations with a large slab of Himalayan rock salt, but they’re great technicians. They’ll keep you alive when you have a heart attack, fix a broken bone, remove torn cartilage from your knee, pull a tooth, stop an infection, and save the lives of mother and child during a difficult birth. And sometimes meds are necessary. Do your homework. Don’t take their word for everything. They aren’t omniscient. But don’t ignore them, either.

Being Primal is about taking advantage of both ancient traditional wisdom and modern science. We have the best of both worlds at our disposal. Take advantage.

10. Buying too many things

This isn’t exactly the most self-serving. I sell supplements and Primal Kitchen fare, and I’m damn proud of all of it. But these are supplements to an already healthy diet. They’re meant to buttress anything missing from your diet, to support you when you can’t quite get the nutrients you need. They’re insurance. And the mayo, avocado oil, and salad dressings I sell aren’t replacing real food; they’re enhancing it. They’re making tuna taste better. They’re giving you a reason to eat more leafy greens. They’re providing a way to healthfully sauté your meat and veggies.

If you find the Primal/paleo way of life is leading you to buy more things and eat more processed food, it’s probably the wrong way. At its heart this movement is about eating real food and enjoying life.

Any of that sound familiar? Fess up. What mistakes are you making? Also, which other common mistakes do you see Primal folks make?

Thanks for reading, everyone. Take care.

Prefer listening to reading? Get an audio recording of this blog post, and subscribe to the Primal Blueprint Podcast on iTunes for instant access to all past, present and future episodes here.

Like This Blog Post? Subscribe to the Mark's Daily Apple Newsletter and Get 10 eBooks and More Delivered to Your Inbox for FREE

April 26, 2016

Why What You Walk (or Run) on Matters

I’ve always preferred traversing natural surfaces. Growing up in New England, I developed my cross country running chops actually running across the country surrounding my house. My favorite endurance events were those involving trees and trails to the point that I might still be doing them if they were exclusively nature-based. Even today, I cherish my hikes through the Malibu hills and rather begrudgingly go for neighborhood walks only because the sidewalk is so convenient. Walking on flat, linear, manmade surfaces is certainly fine, especially if I’ve got my wife or dog or a friend—or I’m exploring a new city—but naturally deposited ground full of dips and peaks and studded with random deformations is ideal.

I’ve always preferred traversing natural surfaces. Growing up in New England, I developed my cross country running chops actually running across the country surrounding my house. My favorite endurance events were those involving trees and trails to the point that I might still be doing them if they were exclusively nature-based. Even today, I cherish my hikes through the Malibu hills and rather begrudgingly go for neighborhood walks only because the sidewalk is so convenient. Walking on flat, linear, manmade surfaces is certainly fine, especially if I’ve got my wife or dog or a friend—or I’m exploring a new city—but naturally deposited ground full of dips and peaks and studded with random deformations is ideal.

And there’s growing evidence that it’s better for you, too.

I’ll ignore the grounding/earthing issue for now. I’ve covered grounding before and it’s difficult, maybe impossible, to disentangle the proposed effects of electron transfer from the known effects of walking barefoot through natural settings.

I’ll also ignore the footwear, even though it certainly matters. You guys know that, so I’ll assume that we’re all in minimalist-type shoes or none at all. Thick-soled shoes dampen the experience and benefits of traversing natural terrain. If you’re wearing hiking boots, walking surfaces don’t matter much; your feet are too sedentary to notice a difference.

Let’s just get straight to it: our hunter-gatherer ancestors walked exclusively across natural, uneven surfaces. Sometimes it was hard (hard stone carved by glaciers). Sometimes it was soft (sand, loamy earth). Sometimes it was firm but forgiving (jungle floors, dirt trails). But it was never linear. Often it was along pathways littered with debris and local deformations formed through natural footfalls and animal movements, not by large work crews wielding pneumatic tampers. Those are the qualities characterizing the evolutionary environment of the human foot:

Asymmetry: The world isn’t balanced. The trail isn’t the same every time you step. There’s the rock under your foot, the root jutting out, the anthill, the acorns, the slope.

Non-linearity: They curve and meander, dip and rise. You have to think when you walk on a trail. You have to be aware.

Hardness: Most natural surfaces are softer than artificial surfaces. Not always (like the aforementioned hard stone) but usually.

Elevation changes: You go up and down. You climb, which uses one neuromuscular pattern, and descend, which uses another.

Unpredictability: You could slip on a slick rock, step into a puddle obscured by leaves. Walking on a manmade surface, you (and your brain) know what you’re getting. Walking on natural surfaces, you, your brain, and your feet must constantly adjust to unforeseen perturbations. They are different every single time, so you can’t predict them. You’re always learning, always accumulating a library of foot-surface interactions.

Modern walking environments are nice. They’re easy and convenient. They’re comfortable to walk on. You can go for miles and miles on pavement without getting too sore or tired. But they’re too comfortable, easy, and convenient for our bodies, which need adversity to function best. Think about strength training and hard sprints: those are acute bouts of adversity that make us stronger and faster and healthier. Just like our bodies adapt to sedentary life, we adapt to walking along the same surface. And whether you’re walking in Des Moines, Manhattan, or Los Angeles, it’s the same basic walking surface. Your older, more medieval cities across the rest of the world tend to have more interesting walking surfaces (cobblestones, stone parquet flooring, etc), but the general trend in civilization’s walking surfaces bends toward uniformity and predictability.

Most terrain/walking surface research focuses on running and formal training rather than walking. Walking is quite pedestrian, many scientists assume, and deserves little scrutiny. No matter; the effects of running and training on various surfaces are just more pronounced versions of walking on the same surfaces. Any changes that occur with one will probably manifest in the other, albeit at different rates. Running on concrete will be much harder on your body much faster than walking on concrete. With that in mind, let’s look at some research.

Natural surfaces affect the cost of movement

Movement expends energy. More difficult movements expend more energy. Easier movements expend less energy. The softness of the walking surface changes the bioenergetics of movement because you “sink” into it. That’s why walking through sand requires as much as 2.5 times the energy it takes to walk on hard surface at the same speed and snow walking (without snowshoes) triples energy expenditure.

The flatness of the walking or running surface also affects bioenergetics. Running on uneven terrain (trail running) increases energy expenditure by 5%, step width variability by 27%, and step length variability by 26%. In addition to increasing step width and length variability and overall lower body muscle activation, walking on uneven terrain also increases hip and knee flexion.

There’s some evidence that these differential effects can have training benefits. In one study, 60-75 year old women followed an eight-week walking program. Half walked on soft sand and half walked on a firm surface. Both groups improved their fitness, but the sand walkers experienced greater gains in hip strength. For a population uniquely afflicted with osteoporosis and hip fractures (about 200,000 occur each year in the US), stronger hip musculature and by extension greater hip bone density could make a huge difference in health and quality of life.

Sprinting on sand forces maximal expression of metabolic output, muscle activation, and energy expenditure while reducing speed and impact shocks. Your body “thinks” it’s sprinting, and you’re working as hard as you can and enjoying (well, not sure “enjoying” is the right word) the metabolic training effects, but you aren’t forcing your body to go faster than it’s capable or subjecting your joints to the jarring impacts of regular flat-ground sprinting. This could be great for older folks whose bodies can’t handle the top speeds and forces of all-out sprinting but still want the benefits.

Tracking gait alterations can predict diabetic neuropathy before traditional symptoms arise in older diabetics, and natural surfaces work better than flat treadmills. Having them walk on actual uneven walking surfaces reveals predictive gait disturbances far earlier than treadmill walking. By the time you’re unsteady on a flat treadmill, it may be too late.

Natural surfaces change loading

Running on grass attenuates overall body loading and changes the distribution of forces across the foot. When you run on a hard surface (concrete or asphalt in one study), you expose your feet to greater forces. When you run on grass, forces are 9.3% to 16.6% lower in the rearfoot and 4.7% to 12.3% lower in the forefoot. Not even running on a rubber track (which is supposed to be easier on the joints) is any less forgiving than running on grass. Another study found that running on grass places significantly lighter loads on both the forefoot and rearfoot than asphalt.

Fake grass isn’t much better. On fake turf, running places significantly greater loading on the lesser toes (everything but the big toe) and central forefoot and slightly less on the medial forefoot and lateral midfoot.

Overall, both running and walking on grass reduce the maximum plantar pressure exerted across the entire foot. Little research on dirt and earth exist, but these results for grass should carry over to other natural surfaces too.

What’s plainly obvious is that the research is lacking. While we have a pretty good idea of what walking on sand and grass does to our feet, body, and bioenergetics, that’s about it. What about walking on cobblestones? Running on gravel? Sprinting through snow? Only real way is to just get out there and give it a try.

Try walking along a creek on top of rocks. Go barefoot. Extra points if they move and roll and tumble. Extra extra points if you don’t slip.

Try walking on a surface that shifts under your feet. While I wouldn’t advise traversing active lava, you could find a hike with loose dirt or gravel. Better yet, climb a hill with loose dirt or gravel.

Lack of research aside, more walking surface variability is better. Low variability exposes your body to repetitive stressors and joint articulations, increasing the risk of overuse injuries. Plus, and this is a big one, walking on flat, even, linear, predictable surfaces is just boring.

What’s your experience walking, running, and training on natural versus artificial surfaces? What do you prefer?

Thanks for reading, everyone. Take care.

Prefer listening to reading? Get an audio recording of this blog post, and subscribe to the Primal Blueprint Podcast on iTunes for instant access to all past, present and future episodes here.

Why What You Walk (or Run) On Matters

I’ve always preferred traversing natural surfaces. Growing up in New England, I developed my cross country running chops actually running across the country surrounding my house. My favorite endurance events were those involving trees and trails to the point that I might still be doing them if they were exclusively nature-based. Even today, I cherish my hikes through the Malibu hills and rather begrudgingly go for neighborhood walks only because the sidewalk is so convenient. Walking on flat, linear, manmade surfaces is certainly fine, especially if I’ve got my wife or dog or a friend—or I’m exploring a new city—but naturally deposited ground full of dips and peaks and studded with random deformations is ideal.

I’ve always preferred traversing natural surfaces. Growing up in New England, I developed my cross country running chops actually running across the country surrounding my house. My favorite endurance events were those involving trees and trails to the point that I might still be doing them if they were exclusively nature-based. Even today, I cherish my hikes through the Malibu hills and rather begrudgingly go for neighborhood walks only because the sidewalk is so convenient. Walking on flat, linear, manmade surfaces is certainly fine, especially if I’ve got my wife or dog or a friend—or I’m exploring a new city—but naturally deposited ground full of dips and peaks and studded with random deformations is ideal.

And there’s growing evidence that it’s better for you, too.

I’ll ignore the grounding/earthing issue for now. I’ve covered grounding before and it’s difficult, maybe impossible, to disentangle the proposed effects of electron transfer from the known effects of walking barefoot through natural settings.

I’ll also ignore the footwear, even though it certainly matters. You guys know that, so I’ll assume that we’re all in minimalist-type shoes or none at all. Thick-soled shoes dampen the experience and benefits of traversing natural terrain. If you’re wearing hiking boots, walking surfaces don’t matter much; your feet are too sedentary to notice a difference.

Let’s just get straight to it: our hunter-gatherer ancestors walked exclusively across natural, uneven surfaces. Sometimes it was hard (hard stone carved by glaciers). Sometimes it was soft (sand, loamy earth). Sometimes it was firm but forgiving (jungle floors, dirt trails). But it was never linear. Often it was along pathways littered with debris and local deformations formed through natural footfalls and animal movements, not by large work crews wielding pneumatic tampers. Those are the qualities characterizing the evolutionary environment of the human foot:

Asymmetry: The world isn’t balanced. The trail isn’t the same every time you step. There’s the rock under your foot, the root jutting out, the anthill, the acorns, the slope.

Non-linearity: They curve and meander, dip and rise. You have to think when you walk on a trail. You have to be aware.

Hardness: Most natural surfaces are softer than artificial surfaces. Not always (like the aforementioned hard stone) but usually.

Elevation changes: You go up and down. You climb, which uses one neuromuscular pattern, and descend, which uses another.

Unpredictability: You could slip on a slick rock, step into a puddle obscured by leaves. Walking on a manmade surface, you (and your brain) know what you’re getting. Walking on natural surfaces, you, your brain, and your feet must constantly adjust to unforeseen perturbations. They are different every single time, so you can’t predict them. You’re always learning, always accumulating a library of foot-surface interactions.

Modern walking environments are nice. They’re easy and convenient. They’re comfortable to walk on. You can go for miles and miles on pavement without getting too sore or tired. But they’re too comfortable, easy, and convenient for our bodies, which need adversity to function best. Think about strength training and hard sprints: those are acute bouts of adversity that make us stronger and faster and healthier. Just like our bodies adapt to sedentary life, we adapt to walking along the same surface. And whether you’re walking in Des Moines, Manhattan, or Los Angeles, it’s the same basic walking surface. Your older, more medieval cities across the rest of the world tend to have more interesting walking surfaces (cobblestones, stone parquet flooring, etc), but the general trend in civilization’s walking surfaces bends toward uniformity and predictability.

Most terrain/walking surface research focuses on running and formal training rather than walking. Walking is quite pedestrian, many scientists assume, and deserves little scrutiny. No matter; the effects of running and training on various surfaces are just more pronounced versions of walking on the same surfaces. Any changes that occur with one will probably manifest in the other, albeit at different rates. Running on concrete will be much harder on your body much faster than walking on concrete. With that in mind, let’s look at some research.

Natural surfaces affect the cost of movement

Movement expends energy. More difficult movements expend more energy. Easier movements expend less energy. The softness of the walking surface changes the bioenergetics of movement because you “sink” into it. That’s why walking through sand requires as much as 2.5 times the energy it takes to walk on hard surface at the same speed and snow walking (without snowshoes) triples energy expenditure.

The flatness of the walking or running surface also affects bioenergetics. Running on uneven terrain (trail running) increases energy expenditure by 5%, step width variability by 27%, and step length variability by 26%. In addition to increasing step width and length variability and overall lower body muscle activation, walking on uneven terrain also increases hip and knee flexion.

There’s some evidence that these differential effects can have training benefits. In one study, 60-75 year old women followed an eight-week walking program. Half walked on soft sand and half walked on a firm surface. Both groups improved their fitness, but the sand walkers experienced greater gains in hip strength. For a population uniquely afflicted with osteoporosis and hip fractures (about 200,000 occur each year in the US), stronger hip musculature and by extension greater hip bone density could make a huge difference in health and quality of life.

Sprinting on sand forces maximal expression of metabolic output, muscle activation, and energy expenditure while reducing speed and impact shocks. Your body “thinks” it’s sprinting, and you’re working as hard as you can and enjoying (well, not sure “enjoying” is the right word) the metabolic training effects, but you aren’t forcing your body to go faster than it’s capable or subjecting your joints to the jarring impacts of regular flat-ground sprinting. This could be great for older folks whose bodies can’t handle the top speeds and forces of all-out sprinting but still want the benefits.

Tracking gait alterations can predict diabetic neuropathy before traditional symptoms arise in older diabetics, and natural surfaces work better than flat treadmills. Having them walk on actual uneven walking surfaces reveals predictive gait disturbances far earlier than treadmill walking. By the time you’re unsteady on a flat treadmill, it may be too late.

Natural surfaces change loading

Running on grass attenuates overall body loading and changes the distribution of forces across the foot. When you run on a hard surface (concrete or asphalt in one study), you expose your feet to greater forces. When you run on grass, forces are 9.3% to 16.6% lower in the rearfoot and 4.7% to 12.3% lower in the forefoot. Not even running on a rubber track (which is supposed to be easier on the joints) is any less forgiving than running on grass. Another study found that running on grass places significantly lighter loads on both the forefoot and rearfoot than asphalt.

Fake grass isn’t much better. On fake turf, running places significantly greater loading on the lesser toes (everything but the big toe) and central forefoot and slightly less on the medial forefoot and lateral midfoot.

Overall, both running and walking on grass reduce the maximum plantar pressure exerted across the entire foot. Little research on dirt and earth exist, but these results for grass should carry over to other natural surfaces too.

What’s plainly obvious is that the research is lacking. While we have a pretty good idea of what walking on sand and grass does to our feet, body, and bioenergetics, that’s about it. What about walking on cobblestones? Running on gravel? Sprinting through snow? Only real way is to just get out there and give it a try.

Try walking along a creek on top of rocks. Go barefoot. Extra points if they move and roll and tumble. Extra extra points if you don’t slip.

Try walking on a surface that shifts under your feet. While I wouldn’t advise traversing active lava, you could find a hike with loose dirt or gravel. Better yet, climb a hill with loose dirt or gravel.

Lack of research aside, more walking surface variability is better. Low variability exposes your body to repetitive stressors and joint articulations, increasing the risk of overuse injuries. Plus, and this is a big one, walking on flat, even, linear, predictable surfaces is just boring.

What’s your experience walking, running, and training on natural versus artificial surfaces? What do you prefer?

Thanks for reading, everyone. Take care.

Like This Blog Post? Subscribe to the Mark's Daily Apple Newsletter and Get 10 eBooks and More Delivered to Your Inbox for FREE

April 25, 2016

Dear Mark: Saturated Fat Jet Lag, Collagenous Amino Acids, and Different Cutting Diets

For today’s edition of Dear Mark, I’m answering three questions. The first concerns a recent study seeming to show that saturated fat disrupts our circadian rhythms, especially saturated fat at the wrong time of day. Should we—yet again—trade butter for soybean oil? Second, how necessary are the amino acids found in collagen? Aren’t they found all over the place, not just in collagen? And finally, I answer a couple questions about cutting diets (those traditionally low-fat, low-carb, high-protein diets) and if they can be adapted to a primal way of eating.

For today’s edition of Dear Mark, I’m answering three questions. The first concerns a recent study seeming to show that saturated fat disrupts our circadian rhythms, especially saturated fat at the wrong time of day. Should we—yet again—trade butter for soybean oil? Second, how necessary are the amino acids found in collagen? Aren’t they found all over the place, not just in collagen? And finally, I answer a couple questions about cutting diets (those traditionally low-fat, low-carb, high-protein diets) and if they can be adapted to a primal way of eating.

Let’s go:

Dear Mark,

What’s your take on this study: https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases...

It says saturated fats disrupt the circadian rhythm and lead to metabolic dysfunction unless you eat them in the morning. Thoughts?

This paper is another in a long line that exposes cells in petri dishes to isolated palmitic acid and extrapolates the results out to whole foods diets. And yes, it’s really easy to find lots of corroborating evidence for the evils of isolated palmitic acid, particularly isolated palmitic acid petri dish bathing:

Palmitic acid lowers expression of the LDL receptor gene. Less LDL receptor activity means LDL hangs around longer in the blood, has more time to become oxidized and cause trouble.

Isolated palmitic acid is toxic to isolated skeletal muscle cells. It impairs glucose uptake and increases insulin resistance. It’s generally good for muscles to accept glucose and respond to insulin.

Palmitic acid induces an inflammatory state and disrupts insulin signaling, two harbingers of diabetes. Nobody wants diabetes.

Palmitic acid damages heart muscle cells. The heart’s quite important.

It’s all scary stuff. It’s enough to make you swear off butter and become a fervent defender of orangutan habitats in palm oil-production zones. Except:

Introducing oleic acid, a monounsaturated fat almost invariably found alongside palmitic acid in the animals we eat (or in the olive oil we use to dress our meat), completely obliterates the inflammation.

A small amount of oleic acid also stimulates LDL receptor activity.

Arachidonic acid, a PUFA found in animal products often alongside palmitic acid, prevents palmitate-induced lipotoxicity.

In other words, palmitic acid in the wild is never alone. It always comes with these mitigating fatty acids, like oleic or arachidonic acid.

Now, the recent study you reference may be different. Maybe the circadian-disrupting effect of palmitic acid isn’t offset by oleic acid or any other whole food nutrients. It’s possible. But I doubt it, given the track record.

These petri dish studies aren’t useless, of course. They do provide mechanisms that occur in the real world. The petri dish isolates everything: the object (the cell line), the environment (the dish), the actor (the palmitic acid), the effect. It’s all singular, refined, granulated. But that’s just the one mechanism, unaltered and unbound. Everything changes when you introduce other variables, like, I don’t know, other fatty acids.

Don’t throw this one out. Integrate it. Maybe it’d be cool to try eating most of your fat earlier in the day. Maybe you’ll sleep better. Maybe eating some sardines (a good source of DHA, the PUFA the scientists discovered did not impair circadian rhythm) alongside your saturated fat is a good idea. Maybe don’t use that Just don’t forget that scientists use these specific nutrients in isolated unrealistic conditions to study an isolated mechanism. They’re not saying you can’t eat butter anymore.

And if they are, they’re wrong.

I have taught a little bio cheese and physiology and so I would like to understand something regarding eating collagen.

When we eat collagen, we would normally break it down into its component amino acids and then absorb those amino acids. Then we would process it and synthesize new collagen with those amino acids. But these amino acids are found in many other proteins – so why do we need to eat collagen?

this doesn’t make sense to me.

First of all, I would love to learn about bio cheese. Sounds delicious.

Second, it’s true that glycine can be found in other protein sources. But collagen is concentrated in only some of them. It’s a supplement that replaces a missing yet vital element of the traditional human diet: skin, bones, and connective tissue. If you look at the top sources of glycine, they’re mostly all odd bits of the animal. Lungs, hocks, skin, ears, and other assorted and delicious oddities. And at the very top is isolated gelatin, which is entirely collagen. You can get glycine from other sources like muscle meat, but it’s not enough and you’ll also be getting a massive dose of methionine, the amino acid that must be balanced with adequate amounts of glycine.

Hi there,

Very interesting website. I am very interested in your opinion on the following question:

Is it healthier/better to do a low calorie, low fat ketosis diet (eg. popular diets such as the max 500 calorie lean protein, no/low fat, with only a small amount of veggie/fruit), or a more moderate primal diet where you are not necessarily in ketosis?

Does the insulin resistance side effect of ketosis diets make those diets less preferable to a more moderate primal diet which is not dependent on ketosis? IE, is it healthier/wiser to do ‘sweet spot’ weight loss, (as much as the alternative fast weight loss that comes from the ketosis phase might be attractive to some people….)

Thanks so much!

Those extreme low-fat, low-carb, high-protein diets, also known as protein-sparing modified fasts (PSMF), certainly can work. In the literature, longer term PSMFs are always done under medical supervision with plenty of biomarker monitoring and supplementation. Out of the clinic, they are good short term hacks if done properly. If you’re on your own, the safest way is to alternate them with days of normal eating. Something like 1-2 days on a normal diet followed by a day of PSMF. Repeat. More seasoned dieters can do them for a few days to a week to cut weight quickly, particularly as you approach your goal weight but still have stubborn body fat to shed. Just be careful.

I prefer the standard Primal eating plan, of course. It allows for greater diversity of food and a wider array of nutrients. It’s more sustainable, pleasurable, and, well, normal. But you can always throw in a round or two of PSMF (even a Primal PSMF) for variety and quicker weight loss.

As for insulin resistance from ketosis or very low-carb dieting, it depends.

Insulin resistance is okay as long as you’re not eating carbs and generating lots of insulin. This is physiological insulin resistance, where what little glucose you have is spared for the brain and the rest of your tissues rely on fat and ketones for energy. It’s actually a feature, not a bug.

If you’re wolfing down carbs willy nilly whenever the mood strikes you, you’re not going to be in ketosis but, because of the high-fat intakes, you will be insulin resistant. That’s a recipe for metabolic dysfunction and weight gain. You have to be strategic about combining carbs and ketosis. Eat them around intense workouts that burn a lot of glycogen. If you have glycogen stores to fill, or “glycogen debt,” any carbs you eat will go toward restoring those glycogen stores and won’t interfere with ketone production. It’s pretty cool.

Hope that helps!

That’s it for today, everyone. Be sure to offer your own experience or expertise down below if you have something that might help today’s questioners. Thanks!

Like This Blog Post? Subscribe to the Mark's Daily Apple Newsletter and Get 10 eBooks and More Delivered to Your Inbox for FREE

April 24, 2016

Weekend Link Love – Edition 397

Check out my interview with Chris Kresser. I cover the gamut, including my early days as an endurance athlete.

Research of the Week

The same genes that determined our big brains may have also given us bigger bodies.

Sun exposure during pregnancy may help prevent asthma in the unborn.

Avoiding the sun is more dangerous than smoking.

Older adults who lift twice a week have a lower chance of dying early.

Adherence to paleo and Mediterranean diet patterns is inversely correlated with inflammatory markers.

Red raspberry research is exploding. Turns out they’re pretty good for you.

Dolphins talk each other through problem solving.

A new study counters previous research on honey.

New Primal Blueprint Podcasts

Episode 116: The Wim Hof Method with Jared Tavasolian and Chris Tai Melodista: Today’s episode features Jared and Chris, the only instructors in the US of the Wim Hof Method. Learn how changing your breathing can improve your breath and cold tolerance and give you the ability to consciously control your autonomic nervous system, immune system, and heart.

Each week, select Mark’s Daily Apple blog posts are prepared as Primal Blueprint Podcasts. Need to catch up on reading, but don’t have the time? Prefer to listen to articles while on the go? Check out the new blog post podcasts below, and subscribe to the Primal Blueprint Podcast here so you never miss an episode.

8 Ayurvedic Herbs That Actually Work

Do Foam Rollers Actually Work?

Why Hobbies Are an Important Part of Primal Living

12 Surprising Things You Can Do With Avocado Oil

Interesting Blog Posts

Kevin Kelly’s optimistic vision of VR. I gotta admit, it makes me feel a little better about it.

“Weight is the best measure of energy balance,” said the man through his voluminous mustache.

Bill Lagakos thinks breakfast is important.

How Robb Wolf feeds his (mostly) paleo kids.

Media, Schmedia

75% of dogs worldwide aren’t pets. So what are they?

The LA Times did a cover story on Dr. Ron Sinha and the scourge of diabetes and metabolic syndrome in Asians.

Are Millennials replacing bar crawls, nightcaps, and Spring Break with juice crawls, mindfulness, and shamanistic retreats?

Everything Else

In a round of rapid responses to the re-evaluated Minnesota Coronary Experiment data, Colpo destroys Willett.

Jarawas: “No, really. We’re good here.”

Working over 50 hours a week gives diminishing returns.

Oh, speed reading. If only you were real.

China’s eating less foreign fried chicken.

Whole Foods is shifting to slower-growing (and better-tasting) chickens.

Teenage sleep: their lives depend on it.

Primal Endurance athlete Gordo Byrn talks fatherhood, training and aging.

Recipe Corner

Dark chocolate sorbet with olive oil and sea salt. This dessert is about as healthy as dessert’s gonna get.

Nothing quite like good breakfast sausage.

Time Capsule

One year ago (Apr 27 – May 3)

Do Low-Carb Diets Cause Insulin Resistance? – And what does it all mean?

The Importance of Non-Negotiable, “No Matter What” Rules – Boundaries are good.

Comment of the Week

K-Starr would say that foam rollers can be used to create shear, but are a pretty weak stimulus for breaking up stuck fascia and improving mobility. My understanding is that he sleeps on a bed of battlesaws held together by mobility bands with a wolverine for a pillow.

– How could I have forgotten the wolverine? Thanks, Investigator.

April 23, 2016

Chicken Bone Broth Four Ways

Just like beef bone broth, the flavor of chicken broth can be transformed by adding a variety of nourishing and invigorating ingredients.

Just like beef bone broth, the flavor of chicken broth can be transformed by adding a variety of nourishing and invigorating ingredients.

For example, here are some killer flavor enhancers: ginger, garlic, kombu, spices, herbs, citrus, coconut milk and fish sauce. Simmering these ingredients in chicken broth gives you something that’s more flavorful than plain broth, but not quite a pot a soup.

Need a basic chicken broth recipe to get you started? There’s one at the end of this post.

Servings: Makes 2 quarts/2 L flavored broth

Time in the Kitchen: 45 minutes

Ginger, Turmeric and Kombu Chicken Broth

2 quarts chicken bone broth (2 L)

2 tablespoons olive oil or butter

1 2-inch piece of ginger, peeled and finely chopped

4 garlic cloves, finely chopped

1 tablespoon grated fresh turmeric root

2 4-6″ strips kombu

Directions:

In a heavy soup pot, warm the oil over medium heat. Add the ginger and cook until it begins to brown, 5 minutes. Add garlic and turmeric root. Cook 2 minutes more.

Add stock and kombu. Cover and simmer 20 minutes.

Spicy Chicken Broth

2 quarts chicken bone broth (2 L)

4 dried chiles de arbol

2 fresh jalapenos, halved lengthwise

1 tablespoon coriander seeds

1 lime

Pour broth into a soup pot and bring to a boil. Add dried chiles, jalapeno and coriander seeds. Cover, reduce heat, and simmer 30 to 50 minutes, until the broth tastes spicy enough for your taste. Strain out solids. Finish broth with a squeeze of lime, if desired.

Thai Chicken Broth

2 quarts chicken bone broth (2 L)

1 tablespoon coconut oil

1 lemongrass stalk (tough outer layer removed) lightly smashed with the flat side of a knife then coarsely chopped

1 1-inch piece ginger, peeled, finely chopped

4 garlic cloves, finely chopped

7 ounces (half a can) coconut milk

2 teaspoons fish sauce

1 tablespoon coconut aminos

Heat oil in a soup pot over medium. Add lemongrass and ginger and cook until softened, 5 minutes. Add garlic and cook a minute or two more.

Add broth, coconut milk, fish sauce and coconut aminos. Bring to a boil then reduce heat and simmer 15 to 20 minutes.

Fresh Herb Chicken Broth

2 quarts chicken bone broth (2 L)

12 stems fresh dill

12 stems fresh parsley

6 sprigs fresh thyme

2 sprigs fresh rosemary or sage

Using kitchen twine, tie the herbs together. Bring the stock to a boil and toss the bundle of herbs in. Reduce heat to a simmer. Cover and cook 25 minutes.

Basic Chicken Bone Broth Recipe

When making chicken broth, a good ratio of water to chicken parts is a quart of water for every pound of chicken. If you have room in the pot to add more chicken parts, go for it. For chicken broth, two hours is enough to extract flavor and gelatin.

To make chicken broth, a whole chicken can be used if you also want meat, but using just wings and backs will make a very flavorful and gelatin-rich broth (especially if you throw in a chicken foot or two).

Ingredients:

4 to 5 pounds chicken and/or chicken parts

1 onion, chopped

2 carrots, chopped

2 ribs celery, chopped

2 cloves garlic, peeled and chopped

6 sprigs parsley

Instructions:

Combine all the ingredients, plus 4 quarts cold water, in a large stock pot. Bring to a boil, reduce heat, and simmer gently for 2 to 3 hours. Skim off any scum that rises to the top.

Strain solids from the stock. Let cool completely than refrigerate (3 to 5 days) or freeze (3 months).

April 22, 2016

From the Strain of Conventional Wisdom to the Ease of Going Primal

It’s Friday, everyone! And that means another Primal Blueprint Real Life Story from a Mark’s Daily Apple reader. If you have your own success story and would like to share it with me and the Mark’s Daily Apple community please contact me here. I’ll continue to publish these each Friday as long as they keep coming in. Thank you for reading!

Malc from England here, sharing my Primal Blueprint success story.

Malc from England here, sharing my Primal Blueprint success story.

It’s not a headline grabbing tale of huge weight-loss, cured illnesses or drastic transformation. It’s about longevity and in particular enjoyment of strength training balanced with starting a family and growing older.

It begins almost 15 years ago when I went off to university. I was 20 and ready to enjoy myself away from home. I threw myself into the lifestyle of 4am bedtimes, mid-day wake-ups, booze most days (if not every day) and plenty of it, accompanied by the obligatory fast food. I’d never been the thinnest of kids, but I’d always played football (soccer) and been reasonably active, so I hadn’t previously struggled with my weight. Of course the new lifestyle took a toll. I reached the heaviest I have ever been (175 pounds at 5’7″).

By the spring term I wasn’t happy at all with my appearance and knew that I wanted to make a change. Luckily one of my good friends was a rugby player at a decent level who spent a fair bit of time in the gym. So I started going to the gym with him. I didn’t know a lot about working out, but I would just crank out “chronic cardio”—i.e., hard running on the treadmill or x-trainer, stationary bike, etc., and a few accompanying exercises on the resistance machines. As I was a student with time to burn, I went 3-5 times a week and did manage to shift some of the timber. But I was having to work damn hard to do it. As Mark says, I was “digging a hole to put a ladder in, so I could climb up to wash the ground floor windows” by exercising hard but undoing it all with diet, booze and lack of sleep.

By the spring term I wasn’t happy at all with my appearance and knew that I wanted to make a change. Luckily one of my good friends was a rugby player at a decent level who spent a fair bit of time in the gym. So I started going to the gym with him. I didn’t know a lot about working out, but I would just crank out “chronic cardio”—i.e., hard running on the treadmill or x-trainer, stationary bike, etc., and a few accompanying exercises on the resistance machines. As I was a student with time to burn, I went 3-5 times a week and did manage to shift some of the timber. But I was having to work damn hard to do it. As Mark says, I was “digging a hole to put a ladder in, so I could climb up to wash the ground floor windows” by exercising hard but undoing it all with diet, booze and lack of sleep.

At the time I actually started to really enjoy the chronic cardio, so over the next year or so I spent less time in the gym and more time running outside, entering 5k and 10k runs, eventually leading to me running the London Marathon in 2004. I trained hard for that marathon and tried to make sure I ate correctly. Or at least according to what Runner’s World, the internet and conventional wisdom said was the correct way to eat. I ate lots and lots of rice and pasta accompanied by small amounts of meat, veg and fruit because “everybody knows” that you need lots of carbs to fuel yourself through those long runs don’t they?? I experimented with carb loading and all the rest of it. But despite the fact that I was “fit” in terms of my ability to run long distances moderately fast, I didn’t look it. I was podgy and pasty looking. Surely I should have been a lean whippet given that I was running 40/50 miles a week in training. Hmmm, what was wrong?

By the time I’d completed the marathon I was a bit bored of all the cardio, so for the next couple of years I returned to the gym sessions, still doing quite a bit of cardio, but starting to scratch the surface of strength training. I read several books about training and with more work in the gym, became a little more muscular but also bigger in general, due to the sheer amount of food I was eating. I now knew that I needed to eat some more protein to help my training, but also thought that I still needed tons of carbs to replenish all the energy I was burning in the gym. At this point I was about 25 and had just graduated with fairly few commitments outside of work, so I would go to the gym five or six days a week, usually doing three strength sessions and two or three cardio sessions. So I was still in fairly good shape, because the amount of training I was doing was balancing the amount of food I was eating.

I was enjoying discovering how deep the rabbit hole of strength and conditioning knowledge goes, and educating myself more and more. I was also in a badly paid, dead-end job that I hated. I had some money left from an inheritance so I decided, “sod it—I hate my job, I love training and I can support myself for a little while. I’m going to quit work and do a course to become a personal trainer.” Three months of full-time learning about the body, exercise and nutrition—what could be better?

I was enjoying discovering how deep the rabbit hole of strength and conditioning knowledge goes, and educating myself more and more. I was also in a badly paid, dead-end job that I hated. I had some money left from an inheritance so I decided, “sod it—I hate my job, I love training and I can support myself for a little while. I’m going to quit work and do a course to become a personal trainer.” Three months of full-time learning about the body, exercise and nutrition—what could be better?

Looking back, doing the course was really useful. But not really in the way that I intended at the time. I did learn a heck of a lot about how to train properly. And that is still certainly useful to me today. I also learnt a lot about nutrition, but unfortunately, mainly from the viewpoint of conventional wisdom and “bro-science.” Funnily enough, looking back through the course materials, they do briefly touch on a “caveman” diet which was quite forward-thinking considering that this was in England back in 2006, when the ancestral health movement was virtually unknown. The course leader was also already an advocate of the caveman diet, I remember her talking about it a few times, but as she was a slightly built woman from a tennis coaching background, and most of the guys on the course were focused mainly on strength training, it was only briefly discussed and of course we all rather dismissed it thinking that we needed to be eating a lot of carbs, some protein and not much fat to get the best results.

By the time I finished the course I was disillusioned with the idea of becoming a personal trainer. What I had failed to realize beforehand, is that although it looks like a fitness related career, it’s primarily a sales job which isn’t really me. But it had at least taken me out of the rut I was in with my old job and I had developed a lot of knowledge that I could put to use on myself. Over the next three or four years I trained hard with some reasonable results, but unfortunately I was still sticking to conventional wisdom around nutrition. I thought that I was doing the right thing by eating food that I had cooked myself, sticking to brown rice, bread and fresh pasta to accompany other fresh ingredients. I still didn’t realize that I was offsetting all my hard work with what I was eating. Slowly doubts started to creep into my mind. I was moving towards my thirties. How was I going to continue training this hard as I got older? I felt like I was starting to grind my body down. What would I do when I couldn’t train so much? Would it all just go to seed?

And then about five years ago I came across The Paleo Diet linked from a health and fitness blog that I read. A lot of the initial reading I did chimed with me as I was already on board with cooking fresh unprocessed food, except that at the time I didn’t understand that things like rice and pasta weren’t unprocessed. However I was still a bit skeptical. Would it provide me with enough carbs to fuel all my workouts? Could I really function with what I perceived as so few carbs in my diet? Conventional wisdom really was “ingrained” in me, pun intended! But I thought what the hell, I’ll give it a try for a while and see how it goes, I can always go back. It wasn’t too big a transition to take out the grains. I bought Robb Wolf’s book and that gave me a much clearer understanding of the principles behind the lifestyle.

Further reading led me to MDA. I became completely hooked. Mark describes everything in such an easy and non-patronizing way that makes complete sense. I read through virtually every article on the site. Now I was really completely on board and an advocate for the lifestyle. Of course, all the while I carried on with my training. It was like someone had given me a new lease of life. Suddenly I felt really, really good. Instead of carrying around a layer of puppy fat like when I was following conventional wisdom, I was actually genuinely lean. It felt pretty nice to have some abs going on for the first time in my life. And as I was turning 30, it was like time was going the wrong way! But the best bit of all was that I no longer had to try, it felt effortless.

For a while I almost tipped over the edge into being “that guy,” militant about persuading people and following the guidance 100%, but over time, I’ve mellowed and allowed a little more leeway back towards the 80/20 rule. I took the advice about training and chronic cardio from Mark, Robb Wolf and others, and throttled back a little. I cut down my strength training to two or three times a week, replaced all my cardio, other than football, with walking (with my wife and son whenever possible) and now I just cruise. I still play football semi-competitively and despite doing no other “cardio,” I have no worries about being able to keep up with the game, despite the fact that most of my opponents are much younger. I’ve also unhooked from the gym. Over the last couple of years, I’ve got really into body-weight strength training. I go to the gym when I fancy and when I don’t, I just use my doorway chin up bar and rings at home. I like being the weird older guy in the gym who wears five-fingers and does handstands, chin ups and pistol squats, while all the younger lads are checking out their guns in the mirror between sets of shoulder presses on the Smith machine and shrugs on the squat rack.

For a while I almost tipped over the edge into being “that guy,” militant about persuading people and following the guidance 100%, but over time, I’ve mellowed and allowed a little more leeway back towards the 80/20 rule. I took the advice about training and chronic cardio from Mark, Robb Wolf and others, and throttled back a little. I cut down my strength training to two or three times a week, replaced all my cardio, other than football, with walking (with my wife and son whenever possible) and now I just cruise. I still play football semi-competitively and despite doing no other “cardio,” I have no worries about being able to keep up with the game, despite the fact that most of my opponents are much younger. I’ve also unhooked from the gym. Over the last couple of years, I’ve got really into body-weight strength training. I go to the gym when I fancy and when I don’t, I just use my doorway chin up bar and rings at home. I like being the weird older guy in the gym who wears five-fingers and does handstands, chin ups and pistol squats, while all the younger lads are checking out their guns in the mirror between sets of shoulder presses on the Smith machine and shrugs on the squat rack.

The lifestyle has also provided plenty of peripheral benefits. I sold my wife on the idea early on and she lost a load of weight too. We love putting our five-fingers on and going walking together. Just over 14 months ago our son was born. We’re now following baby-led weaning using a primal eating plan, and he’s a really healthy and happy little soul. Of course the new demands of fatherhood have had a large impact on my free time available to train and quality of sleep available to recover. In the past that would have been a problem but not now. It’s easy to stay as lean and strong as I want to be just by using the minimum effective dose of training and sticking to a primal lifestyle. I’ve replaced the car commute by cycling the eight miles each way to work, which is time efficient, combining low level frequent movement and the commute in one go. Most of my colleagues thought I was absolutely nuts when I told them I was selling my car at the beginning of winter to start cycling to work. But it’s no bother. It was great to know that I’d have no problem in terms of being fit enough to commute reliably and quickly, when many of my peers simply wouldn’t have the option due to poor general health and fitness levels.

The lifestyle has also provided plenty of peripheral benefits. I sold my wife on the idea early on and she lost a load of weight too. We love putting our five-fingers on and going walking together. Just over 14 months ago our son was born. We’re now following baby-led weaning using a primal eating plan, and he’s a really healthy and happy little soul. Of course the new demands of fatherhood have had a large impact on my free time available to train and quality of sleep available to recover. In the past that would have been a problem but not now. It’s easy to stay as lean and strong as I want to be just by using the minimum effective dose of training and sticking to a primal lifestyle. I’ve replaced the car commute by cycling the eight miles each way to work, which is time efficient, combining low level frequent movement and the commute in one go. Most of my colleagues thought I was absolutely nuts when I told them I was selling my car at the beginning of winter to start cycling to work. But it’s no bother. It was great to know that I’d have no problem in terms of being fit enough to commute reliably and quickly, when many of my peers simply wouldn’t have the option due to poor general health and fitness levels.

I’m almost 35 now and the primal lifestyle has enabled me to find a happy niche that I feel confident I can sustain for many years to come! I have no doubt that barring an unforeseen catastrophe, I’ll be able to maintain my lifestyle pretty much as long as I want to. I’m not worried about training my body into dust, becoming sedentary or sliding into a cycle of insidious weight gain and associated deteriorating health. I’m really looking forward to being able to enjoy playing with my son as he grows up and be able to keep up with whatever games and running around he wants to do, while of course raising him into a comfortable 80/20 primal lifestyle.

So all I can say is a huge thank you Mark for not only sharing your wisdom, but doing so for free!

Malc

April 21, 2016

Why Saying “No” Is So Important

In the health and fitness arena, taglines often sell the idea of “accept no limits.” After all, we’re supposed to believe in ourselves, push through boundaries, improve exponentially and show them all, right? Dramatic images, big numbers and extreme makeovers get the spotlight. And when people work hard for what they achieve, I think it’s great. My own primary focus on MDA is helping people live their best life with the least amount of pain, suffering and sacrifice possible. To that end, I offer ample positive advice for what to do. Inherent to the bigger picture, however, (and just as critical in my opinion) is the skill of discerning what not to do. Today I’m talking limits—and how knowing where to draw the line is essential to living an awesome life.

In the health and fitness arena, taglines often sell the idea of “accept no limits.” After all, we’re supposed to believe in ourselves, push through boundaries, improve exponentially and show them all, right? Dramatic images, big numbers and extreme makeovers get the spotlight. And when people work hard for what they achieve, I think it’s great. My own primary focus on MDA is helping people live their best life with the least amount of pain, suffering and sacrifice possible. To that end, I offer ample positive advice for what to do. Inherent to the bigger picture, however, (and just as critical in my opinion) is the skill of discerning what not to do. Today I’m talking limits—and how knowing where to draw the line is essential to living an awesome life.

I know we all live in a culture of “more is better.” At various points of my life I’ve been tempted by that siren song. (I am a former Cardio King after all.) And yet the last few decades have affirmed a very different truth for myself and for others I’ve observed.

Because of the work I do, I meet a lot of people who are motivated to live a healthier life. It’s one of the things I love most about what I do in fact. And, yet, as a result I also see the full spectrum of behavior around “healthy” action.

Unfortunately, I watched people exercise their way into illness, ironically incapacitating themselves (or at least impairing their weight loss or fitness progress) because they couldn’t respect their bodies’ need for recovery. I’ve even seen others move from healthy eating into destructive orthorexic obsession. I’ve seen professional ambition consume people’s lives, and anxious parenting undermine the capacity for joy.

We reward and esteem those who relentlessly pursue self-improvement, but when does relentless become dysfunctionally desperate? It’s a sad image when what we think we want (or should want) ends up unraveling our chance for genuine balance and well-being.

Think of the times you’ve pushed yourself passed your limits in ways that ended up acting against your own best interest. You know—those times you’ve told yourself that you don’t “deserve” a treat, a break, etc., only to have that abstention come back to bite you. When have you denied yourself reasonable limits for the sake of “more is better”? When have you refused limits that would’ve given you needed sleep, solitude, rest, ease, peace, pleasure or sanity?

Think about the messages that play for you as you make decisions. What virtues are you attempting to uphold in your life, and when do you feel unnecessarily or excessively bound by them? When have you genuinely restricted your enjoyment of life because you can’t find any comfortable compromise in your principles?

Where has dedication become desperation, commitment become compulsion?

Maybe it’s in trying to be the perfect parent/partner/child/friend that we frequently wear ourselves out. Maybe we’re caught in a cycle of unwarranted restriction in our food choices that’s sucking any and all pleasure out of eating. Perhaps we routinely overdo it at the gym or have a hard time justifying relaxing because we always feel we can fit in “one more” walk or should be getting in “one more” set or “one more” hour of activity—only to continually wear ourselves out or leave no opportunity for other more restful and fulfilling activities. Maybe it’s finishing “one more” thing at work even though we know it will mean once again forgoing time with our families or time for ourselves. Perhaps it’s even never knowing when to stop obsessively reading about health and just trust we know what we’re doing.

In short, our lives become victims to the visions we have for them.

What would your life look like if you lived by the rhythm you genuinely feel best serves your mental and physical health? How many of us even know what that rhythm looks like? Do we have a sense of our ideal balance in life? Maybe we should spend as much time discerning our ideal limits as we do planning for our infinite expansion and self-improvement…

They say with age comes experience, and the fact is I’ve come to a finer and more honest awareness of my own human propensity toward excessive control. (Most of us, truth be told, have this in some sense or to some degree.) My resolve has indeed helped me achieve a great deal in life, but my ability to intuit natural limits has actually allowed me to enjoy my life and all I have.

The people I see who push themselves too far have excessive vision without a sense of proportion. It’s what happens, I think, when we abandon our self-attunement in the pursuit of principles. Frankly, when we refuse to have patience for ourselves and our process, it’s an act of self-sabotage (if not self-aggression).

I don’t say this lightly. We all deserve optimum well-being, but I’d also argue we can best attain it (and maintain it) when we foster a sense of informed intuition about our needs—balancing those admirable principles and ambitious goals with instinctual self-care. I’ve heard a friend describe it as living lightly, and that sounds about right.

So, let me open this up to you. What limits have you learned to set for yourself? And how have you learned where to draw those lines? What’s been the impact for your mental and physical health, not to mention other areas of life?

I look forward to reading your thoughts. Thanks for reading, everyone.

Mark Sisson's Blog

- Mark Sisson's profile

- 199 followers