Carl E. Olson's Blog, page 99

April 26, 2014

On the Papacy, John Paul II, and the Nature of the Church

On the Papacy, John Paul II, and the Nature of the Church | By Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger

Excerpts from God and the World: A Conversation with Peter Seewald | Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger

On the Pope and the Papacy:

On the Pope and the Papacy:

Many people have the idea that the Church is an enormous apparatus of power.

Yes, but you must first of all see that these structures are supposed to be those of service. The pope is thus not the chief ruler–he calls himself, since Gregory the Great, "Servant of the servants of God"–but he ought, this is the way I usually put it, to be the guarantor of obedience, so that the Church cannot simply do as she likes. The pope himself cannot even say, I am the Church, or I am tradition, but he is, on the contrary, under constraint; he incarnates this constraint laid upon the Church. Whenever temptations arise in the Church to do things differently now, more comfortably, he has to ask, Can we do that at all?

The pope is thus not the instrument through which one could, so to speak, call a different Church into existence, but is a protective barrier against arbitrary action. To mention one example: We know from the New Testament that sacramental, consummated marriage is irreversible, indivisible. Now, there are movements who say the Pope could of course change that. No, that is what he cannot change. And in January 2000, in an important address to Roman judges, he declared that in response to this movement in favor of changing the indissolubility of marriage, he can only say that the Pope cannot do anything he wants, but he must on the contrary continually rekindle our sense of obedience; it is in this way, so to speak, that he has to continue the gesture of washing people’s feet

The papacy is one of the most fascinating institutions in history. Besides all the instances of greatness, the history of the popes certainly does include some dramatic and abysmal low points. Benedict IX, for example, reigned, even after being deposed, as the 145th pope, as well as the 147th and the 150th. He first mounted the throne of Peter when he was just twelve years old. Nonetheless, the Catholic Church holds fast, with no exceptions, to this office of the vicar of Christ upon earth.

Simply from a historical point of view, the papacy is indeed a quite marvelous phenomenon. It is the only monarchy, as people often put it, that has held out for over two thousand years, and this in itself is quite incomprehensible.

I would say that one of the mysteries that point to something greater is quite certainly the survival of the Jewish people. On the other hand, the endurance of the papacy is also something astonishing and thought provoking. You have already suggested, with one example, how much failure has been involved and how much damage the office has had to suffer, so that by all the rules of historical probability it should have collapsed on more than one occasion. I think it was Voltaire who said, now is the time when this Dalai Lama of Europe will finally disappear, and mankind will be freed from him. But, you see, it carried on. So that’s something that makes you feel: This is not the result of the competence of these people–many of them have done everything possible to run the thing into the ground–but there is another kind of power at work behind this. In fact, exactly the power that was promised to Peter. The powers of the underworld, of death, will not overcome the Church.

On John Paul II:

John Paul II was the firm rock of the twentieth century. The Pope from Poland has left his mark on the Church more clearly than many of his predecessors. His very first encyclical, Redemptor Hominis (The Redeemer of Man), laid out his program: Men, the world, and political systems had, he said, "strayed far from the demands of morality and justice". The Church must now offer the alternative to this, he said, through clear teaching. This fundamental thesis is to be found in all the papal encyclicals. As against the "culture of death", the Church must proclaim a "culture of life". Has John Paul II left the Church the requisite foundation for her to make a good start in the new century?

The true foundation is of course Christ, but the Church always stands in need of new stimulation; she always has to be built up again. Here you can certainly say that this pontificate has left an unusually strong imprint. It was occupied in dealing with all the basic questions of our time–and over and beyond this, it gave us a running start, a real lead.

The pope’s great encyclicals–first Redemptor Hominis, then his Trinitarian triptych, where he depicts the image of God, the great encyclical on morality, the encyclical on life, the encyclical on faith and reason–set standards and, as you have said, show us the foundations on which we can build anew. And for the reason that in this world, which has changed so much, Christianity must find a new expression.

In just such an epoch-making way as Thomas Aquinas had to rethink Christianity in the encounter with Judaism, Islam, and with Greek and Latin culture, so as to give it a positive shape, just as it had to be rethought at the beginning of the modern age–and in that rethinking, it split apart into the Reformed style and the basic outline given by the Council of Trent, which dominated the shape of the Church for five centuries–so today, at the great turning point between epochs, we have both to preserve undiminished the identity of the whole and at the same time to discover the ability of living faith to express itself anew and to make its presence known. And the present Pope has certainly made a quite essential contribution to that.

On The Church:

In the course of two thousand years of Christian history, the Church has divided time and again, In the meantime, there are around three hundred distinguishable Protestant, Orthodox, or other churches. There are way over a thousand Baptists groups in the United States. Over against these there is still the Roman Catholic Church with the pope at her head, which claims to be the only true Church. She remains at any rate, and despite every crisis, indeed the most universal, historically significant, and successful Church in the world, with more members today than at any time in her history.

I think that in the spirit of Vatican II we ought not to see that as a triumph for our prowess as Catholics and ought not to make much of the institutional and numerical strength we continue to enjoy. If we were to reckon that as our achievement and as our right, then we would step outside the role of a people belonging to God and set ourselves up as an association in our own right. And that can very quickly go wrong. A Church may have great institutional power in a country, but as soon as faith is no longer there to back it up, the institution will break down.

Perhaps you know the medieval story of a Jew who traveled to the papal court and who became a Catholic. On his return, someone who knew the papal court well asked him, "Did you realize what sort of things are going on there?" "Yes," he said, "of course, quite scandalous things, I saw it all." "And you still became a Catholic", remarked the other man. "That’s completely perverse!" Then the Jew said, "It is because of all that that I have become a Catholic. For if the Church continues to exist in spite of it all, then truly there must be someone upholding her." And there is another story, to the effect that Napoleon once declared that he would destroy the Church. Whereupon one of the cardinals replied, "Not even we have managed that!"

I believe that we see something important in these paradoxical tales. There have in fact always been plenty of human monstrosities in the Catholic Church. That she still holds together, even if she groans and creaks, that she is still in existence, that she produces great martyrs and great believers, people who put their whole lives at her service, as missionaries, as nurses, as teachers, that really does show that there is someone there upholding her.

We cannot, then, reckon the Church’s success as our own reward, but we may still say, with Vatican II–even if the Lord has given a great deal of life to other churches and communities–that the Church herself, as an active agent, has survived and is present in this agent. And that can only be explained by the fact that he grants what men cannot achieve.

Angelo Roncalli and Priestly Celibacy

Angelo Roncalli and Priestly Celibacy | Fr. Brian Van Hove, S.J. | Ignatius Insight

(Note: The following was originally posted on Ignatius Insight in June 2008.)

Since his death on June 3, 1963, many biographies and studies of Pope John XXIII (Angelo Roncalli) have appeared. In the month of his death was the article of Roger Aubert, "Jean XXIII: Un 'pape de transition' qui marquera dans l'histoire". The same year, and revised in 1981, is Leone Algisi's John the Twenty-Third / Giovanni XXIII. In 1965 there appeared that of Edward Elton Young Hales, Pope John and His Revolution. In 1973 Pope John XXIII by Paul Johnson, and in 1979 Bernard R. Bonnot's Pope John XXIII: An Astute, Pastoral Leader.

We are told the writer who had access to the greatest quantity of primary, original sources is Peter Hebblethwaite. In 1984 the British edition of his John XXIII: Pope of the Council appeared, and in 1985 the American version was published as Pope John XXIII: Shepherd of the Modern World. [1] The Hebblethwaite contribution is considered the "definitive" biography. It was reprinted in 1994. In 2000 and 2005 it was reprinted in a revised and abridged edition by Margaret Hebblethwaite, Peter Hebblethwaite's wife whom he married after leaving the priesthood and the Society of Jesus.

Yet Hebblethwaite never refers to the only source we have on Angelo Roncalli and the question of priestly celibacy. This is curious because the topic has recurred as a burning one during the Enlightenment of the eighteenth century, at the time of the French Revolution, and during the Restoration period of the nineteenth century, especially in the German universities. After the collapse of the Austrian Empire it was addressed specifically by the famous consistorial allocution of Pope Benedict XV on December 16, 1920, when Benedict said priestly celibacy was "irrevocable". A formal schism in Bohemia ensued. [2]

In the period of the Second Vatican Council this was even more exacerbated with reports of neo-concubinage being practiced in parts of Western Europe, South America, Africa, and the Philippines. Some bishops at the Council wanted the question re-examined. The rationale for abolishing it is not new, either, because as early as the time immediately following the French Revolution the "shortage of priests" has been traditionally adduced as sufficient in itself to merit a change in what is looked upon as mere discipline.

We all know that the Second Vatican Council in the end strongly supported the spiritual tradition of priestly celibacy in Presbyterorum ordinis, #16, and that Pope Paul VI strengthened this still further with his encyclical of June 24, 1967, Sacerdotalis caelibatus. Surely along with Humanae vitae it was his most unpopular and "politically incorrect" encyclical.

Yet how often the image of "The Good Pope John" [3] is skillfully invoked by those who wish to abolish priestly celibacy. John XXIII Roncalli was the "good" pope, while Paul VI and his successor John Paul II Wojtila are "bad" popes. They are called intransigent, while he is called open. If only Roncalli had lived long enough, they insist, things might have been different, and this useless and archaic norm might have been done away with. He was open to change, while others have closed the door to change. But the historical record suggests the exact opposite in the question of priestly celibacy. We must reclaim the real Angelo Roncalli of church history.

The eminent historian of science and winner of the Templeton Prize for Religion in 1987, Stanley L. Jaki, reports the following in his article entitled "Man of One Wife or Celibacy" [4]:

It is enough to recall the reply which John XXIII, the proverbial embodiment of compassion, gave to Etienne Gilson who in a private audience in December 1961 touched on the agonizing trials of some priests. For in that reply, later reported by Gilson, one could feel the reverberations of the age-old resolve of the Church: 'The Pope's face became gloomy, darkened by a rising inner cloud. Then the Pope added in a violent tone, almost a cry: "For some of them it is a martyrdom. Yes, a sort of martyrdom. It seems to me sometimes I hear a sort of moan, as if many voices were asking the Church for liberation from the burden. What can I do? Ecclesiastical celibacy is not a dogma. It is not imposed in the Scriptures. How simple it would be: we take up the pen, sign an act, and priests who so desire can marry tomorrow. But this is impossible. Celibacy is a sacrifice which the Church has imposed herself--freely, generously, and heroically".' [5]

As for interpreting the mind of John XXIII Roncalli, Pope John Paul II has done so, addressing bishops, in an explicit reference to seminary formation and the aspirations of the Council: "In particular I ask you to be vigilant that the dogmatic and moral teaching of the Church is faithfully and clearly presented to the seminarians, and fully accepted and understood by them."

On the opening day of the Second Vatican Council, Oct. 11, 1962, John XXIII told his brother bishops: "The greatest concern of the ecumenical council is this: that the sacred deposit of Christian doctrine should be more effectively guarded and taught." What Pope John expected of the council is also a primary concern for priestly formation. We must ensure that our future priests have a solid grasp of the entirety of the Catholic faith; and then we must prepare them to present it in turn to others in ways that are intelligible and pastorally sound. [6]

There is no evidence in the historical record to think the real Angelo Roncalli, John XXIII, was of a mind to compromise on the ancient Catholic spiritual tradition of priestly celibacy. [7] The "Good Pope John" mythology is a problem for us, not a solution. And it is a problem from which we must recover, not only to have a more truthful record, but to be rid of a mechanism that has been used to undermine the requirement of priestly celibacy in the Catholic Church. While appreciating Roncalli's undoubted and real goodness, [8] we should also be led to admire his strength and firmness. He promoted that unique context for priestly life which is demanded by the non-functional and sacrificial nature of the Catholic priesthood itself where the priest is a living icon of Christ.

Exceptions to that norm (the Eastern practice of "one wife before ordination", and the selective case-by-case ordination of once-married convert-clergy originally initiated by Pius XII for Germany, then renewed for new circumstances in the United States in 1980) only highlight its relevance for the whole of the Church.

If every seminarian took a minimum of two semesters of rigorous academic instruction in the history and theology of chaste priestly celibacy, we might partially realize the hopes of the real Pope John XXIII.

An earlier version of this article appeared as "Angelo Roncalli and Priestly Celibacy," Homiletic and Pastoral Review, vol. XCII, nos. 11-12 (August-September 1992): 79-82.

ENDNOTES:

[1] See Peter Hebblethwaite, Pope John XXIII: Shepherd of the Modern World (Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Co., 1985).

Alberto Melloni says in 1986 of Hebblethwaite's work: "Peter Hebblethwaite published in England in October, 1984, and in the United States last spring the most in-depth biography of Pope John XXIII ever printed. The author had the advantage of being able to consult more sources than any other biographer of Roncalli. Neither Leone Algisi nor Meriol Trevor, neither Bernard R. Bonnot nor Paul Dreyfus had access to the 13,000 printed pages (i.e., more than 6,000,000 words) of Roncalli's writings which have not been made available. The same may be said for all those scholars who, during the same years, wrote unsystematic, although sometimes more readable profiles, such as Edward E.Y. Hales' book, Cardinal Giacomo Lercaro's famous lecture, the inquiries of Giancarlo Zizola, and the research carried out by Franz M. William and the Alberigos (whose "Bologna School" often reflects the thought of Giuseppe Dossetti [1913-1996] with special reference to the so-called "spirit" of the council or the council as "event" versus the "letter" of the official documents). Besides all the edited material, Hebblethwaite had access to some unpublished or almost unknown manuscripts and a few other primary sources. This book therefore, deserves a detailed analysis, insofar as it could represent within the limits of the biography format, a valuable synthesis of the knowledge and questions which concern such an important man." Alberto Melloni, "Pope John XXIII: Open Questions for a Biography," The Catholic Historical Review 72 (1986): 51-53.

[2] See Roger Aubert, The Christian Centuries, vol. 5, The Church in a Secularized Society (New York: Paulist Press, 1978), 541-542.

[3] This expression is actually found as a book title: Wit and Wisdom of Good Pope John, collected by Henri Fesquet, translated by Salvator Attanasio (New York: P.J. Kenedy and Sons, 1964). Even the venerable Paul Horgan seems to indulge in the sentimentalizing mode when he credits Pope John with permission to see the archives in the fall of 1959 for his research on Jean Baptiste Lamy. One wonders if he would have so honored Paul VI for granting the same permission. See "The Adventure of the Hundred-Year Proviso", America, March 23, 1991, pp. 309-314.

[4] See Stanley L. Jaki, Catholic Essays (Front Royal, VA: Christendom Press, 1990), pp. 77-91. Hebblethwaite does refer to Elliott, but not to any of his references to Roncalli's attitude to celibacy found on pp. 188-189 and 286-287. See Lawrence Elliott, I Will Be Called John (New York: Reader's Digest Press/E.P. Dutton & Co., 1973).

[5] Ibid., pp. 85-86. Jaki goes on to say: "Gilson released details about his conversation with John XXIII, in a letter to the Parisian weekly, Match then the French equivalent of Life, following the publication there (November 30, 1963) of a splashy and tendentious discussion of priestly celibacy. Gilson's statement was reported in the May 15, 1964, issue of Commonweal (p. 223), and from there found its way into a report on celibacy in Time magazine (Aug. 28, 1964, p. 56) which, although it carried the title, 'The Case Against Celibacy', should seem a paragon of objectivity and decency in comparison with its latter-day reporting on the topic." (n. 6, p. 91). Margaret Hebblethwaite mentions Gilson only in connection with the thought of St. Thomas Aquinas on page 109 of her abridgement John XXIII: Pope of the Century (London and New York: Continuum, 2000 and 2005).

[6] See John Paul II, "The Pope's Address", Part III, Origins 17 [1987], pp. 266-267. Quoted in the context of the nature of the priesthood in Donald J. Keefe, S.J., Covenantal Theology, two volumes (Lanham, MD: The University Press of America, 1991), I: p. 154.

[7] R.C. Zaehner supports this by quoting from Roncalli's book Journal of a Soul. In referring to Paul VI, Zaehner says: "This has led him to act on his own initiative in the matter of both birth control and the celibacy of the clergy. That he has been tactless and heavy-handed on both issues few will deny; but on neither is there any justification for questioning his integrity. Nor is there any reason to suppose that Pope John would have taken a different line; for on 11 August 1961 he wrote in his diary: 'Sins. Concerning chastity in my relations with myself, in immodest intimacies: nothing serious, ever'. Certainly his manner would have been different, but in this matter of chastity he might well have taken as tough a line as his successor but scarcely with the authoritarian overtones that have so distressed the progressives." See Robert Charles Zaehner, Zen, Drugs and Mysticism (New York: Pantheon Books, 1972), p. 204. Carlo Falconi maintains that we can know John XXIII best from his own works, especially the autobiographical ones. See his The Popes in the Twentieth Century From Pius X to John XXIII, tr. Muriel Grindrod (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1967), p. 378. Generally Falconi subscribes to "The Good Pope John" school.

[8] The late Spalding Professor of Eastern Religions and Ethics in the University of Oxford once wrote this of him: "...maybe a saintly priest or two who, like Pope John, are good not because they try to be good but because they don't need to try since they have lost their ego and therefore all egoism, and are thus open to that spontaneity which is the Holy Spirit." See R.C. Zaehner, ibid., p. 133.

Related IgnatiusInsight.com Articles, Interviews, and Book Excerpts:

• Clerical Celibacy: Concept and Method | Alfons Maria Cardinal Stickler

• Pray the Harvest Master Sends Laborors | Rev. Anthony Zimmerman

• The Real Reason for the Vocation Crisis | Rev. Michael P. Orsi

• The Hour That Makes My Day | Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen

• Priestly Vocations in America: A Look At the Numbers | Jeff Ziegler

• Practicing Chastity in an Unchaste Age | Bishop Joseph F. Martino

• Liturgical Roles In the Eucharistic Celebration | Francis Cardinal Arinze

• The Role of the Laity | Carl E. Olson

Father Van Hove, S.J., is on staff at the White House Retreat in South St. Louis County, Missouri.

April 25, 2014

John Paul II's Vision of Family and Marriage for the New Evangelization

Pope John Paul II blesses a baby in the Sistine Chapel on the feast of the Baptism of the Lord in 2002. (CNS photo/Catholic Press Photo)

John Paul II's Vision of Family and Marriage for the New Evangelization | Rolando Moreno | CWR

The family is an active and vital agent in establishing a civilization of love and the renewal of Christian culture

As Catholics reflect on the legacy of St. John Paul II, we will hear a great deal about his papacy and its global impact. However, I am convinced that as time passes he will be memorialized above all—at least by the Church—as a preeminent champion of marriage and family life.

St. John Paul II believed the family would play a vital role in the new springtime of evangelization and was much more than mere bystander in the Church’s evangelizing mission. He presented an inherently positive and bold view of marriage and family life. He was confident that no ideology, however daunting, can extinguish what God has set in motion. While the family finds itself in the midst of an eroding cultural crisis, facing militant attempts to redefine marriage contrary to reason and the Gospel of Jesus Christ, John Paul II redirects our gaze to the truth of Christian marriage as a fruit of the redemption of Christ. He saw the family in its full potential in the order of grace—that if lived according to this potential in Christ, it could change the culture and the world. For John Paul II, the family is an active and vital agent in establishing a civilization of love and the renewal of Christian culture.

As evident from his numerous writings on this topic (most notably “Original Unity of Man and Woman”, Familiaris Consortio and “Letter to Families”), John Paul presented the family as rooted in the economy of salvation—that is, God's act of creating the world and offering salvation through Christ—with an important role to play in the order of redemption. The family, as such, must continue the work of Christ and this work must begin first within itself, within each individual family before affecting the extended community.

Many mistakenly think that magisterial teaching is too theological, and thus impractical, to be effectively used for the work in the Lord’s vineyard. And some may be intimidated by John Paul’s reflections, seeing them as daunting, too philosophical and overly academic. Yet, despite the scholarship and depth of his writing, John Paul had no intention of having his teachings about the human person remain only on the academic level. Rather, his reflections are deeply Christological and Trinitarian, and meant to change lives.

Marriage in the Economy of Salvation

The world, explained John Paul, has been penetrated by the Divine in startling fashion. “For by his incarnation the Son of God united himself in a certain way with every man. The divine mystery of the Incarnation of the Word thus has an intimate connection with the human family” (LF 2). Marriage has a role in the economy of salvation; it is and can be an instrument of redemption for the world. Having been taken up into Christ, it extends to the temporal order, thereby building a civilization of love.

April 24, 2014

Images of the Priest in the Life and Thought of John Paul II

Images of the Priest in the Life and Thought of John Paul II | George Weigel | HPR

If there is one great truth to be learned from the luminous, world-transforming priestly ministry that Karol Wojtyła, Pope John Paul II, gave to the Church, it is this: a true priestly vocation begins with a commitment to radical discipleship.

It has been nine years since the remarkable events that unfolded between February and April, 2005—and still our minds and imaginations, and perhaps our prayers as well, come back, time and again, to the last illness and death of Pope John Paul II. Those memories take on special resonance as his canonization draws near.

It was an extraordinary human drama—perhaps one of the few genuinely global dramas in history. An entire world gathered, metaphorically, around the bed in the papal apartment to help John Paul II through what he called, in his spiritual testament, his “Passover.” Yet, February, March, and early April 2005 unfolded as not just an extraordinary human drama, but as an extraordinary Christian drama and, indeed, an extraordinary priestly drama. For what the world saw (whether it recognized it in these terms or not), and what the Church lived through (and hopefully recognized as such), was manifestly the death of a priest. For the last time, Karol Wojtyła led the Church and the world into an experience of the Paschal Mystery. And that is the essence of the vocation of priests: to lead the Church, and the world, into an experience of the mystery of Jesus Christ, crucified and risen.

How did the late pope do that? As my mind’s eye turns back to those dramatic days, certain vignettes, etched in poignancy, stand out.

I remember the Pope returning to the Vatican from the Policlinico Gemelli hospital on February 10 and March 13, 2005, with throngs of Romans crowding the streets to welcome back the man they had once thought of as lo straniero (“the stranger”) but whom they now thought of, quite literally, as il papa (“father”).

I think of the Pope with a palm branch in his hand at the window of the Apostolic Palace on Palm Sunday.

I remember the Pope in his chapel in the papal apartment on Good Friday evening, holding fast to a crucifix while watching the Via Crucis at the Roman Colosseum on television. On that occasion, the Pope was back-shot, the television camera behind him so that all that you saw were his back and his hands holding that cross. Why, some television commentators asked? It was not, I replied, in order to hide his tracheotomy and his suffering, but rather to underscore the message this most visible of men in history (who had been seen live by more human beings than anyone else, ever) had taken around the world: “Don’t look at me; look at Jesus Christ.”

April 23, 2014

New from Ignatius Press: "The Kerygma: In the Shantytown with the Poor"

Now available from Ignatius Press:

The Kerygma: In the Shantytown with the Poor

by Kiko Argüello

Also available as an Electronic Book Download: The Kerygma

"This is one of those books that, in its simplicity, is full of substance and depth, and it deserves to be read."

- Cardinal Antonio Cañizares Llovera, Prefect of the Congregation for Divine Worship

Francisco ("Kiko") Argüello was an award-winning painter, and an atheist. Struggling with the contrast between his desire for justice and the lack of justice in the world, he adopted existentialism and its explanation of life: everything is absurd.

But if everything is absurd, why paint? For that matter, why even live? Such questions led Argüello to the brink of despair. He called out to God and personally experienced the reality of divine love as revealed in Jesus Christ.

Dedicating his life to Christ, Argüello began living among the very poor. While in a slum on the outskirts of Madrid, Argüello met the lay missionary Carmen Hernández, and together they began proclaiming the good news of salvation to the poorest of the poor. Their method of transmitting faith in Christ and building Christian community has become a model of evangelization. Now known as the "Neocatchumenal Way", it has spread to cities throughout the world and received the approval of the Vatican.

"The Neocatechumenal Way is an itinerary of Christian initiation and of permanent education in faith. Kiko's catechesis, published here, is a strong lesson for disciples. In this catechesis the entire announcement of the Gospel is impressively condensed."

- Cardinal Christoph Schoenborn

"The Neocatechumenal Way a gift of the Holy Spirit to help the Church."

- Pope Benedict XVI

Francisco José Gomez-Argüello Wirtz was born in Leon, Spain, in 1939. He studied fine arts at the Royal Academy of San Fernando in Madrid, where he became a professor of painting and drawing. In 1959 he received Spain's National Prize for Painting. Along with Carmen Hernández he founded the Neocatechumenal Way.

Saint John Paul II, Alive Among the Saints

Saint John Paul II, Alive Among the Saints | Douglas Bushman | Catholic World Report

The great Polish pope constantly emphasized the universal call to holiness as demonstrated in the lives of the saints.

At the outset of his Petrine ministry and several times thereafter, Pope Wojtyla told us that his pontificate was dedicated to the faithful interpretation and implementation of the Second Vatican Council. He also told us that central to the renewal of Vatican II is the universal call to holiness. “[T]his call to holiness is precisely the basic charge entrusted to all the sons and daughters of the Church by a Council which intended to bring a renewal of Christian life based on the Gospel” (Christifideles Laici, 16).

The Jubilee of the Year 2000 was the occasion for him to reassert: “Holiness…has emerged more clearly as the dimension which expresses best the mystery of the Church. Holiness, a message that convinces without the need for words, is the living reflection of the face of Christ” (Novo Millennio Ineunte, 8). In keeping with his constant exhortation to read and to study the texts of Vatican II, he appealed to all to “rediscover the full practical significance of Chapter 5 of the Dogmatic Constitution on the Church Lumen Gentium, dedicated to the ‘universal call to holiness.’”

“[T]he heart of holiness is love” (Ecclesia in America, 30), that is, participation in divine life in and through Christ’s paschal charity, which is the soul of the apostolate, the inner dynamism of all ministry, apostolate, service, and mission. “[T]he call to the mission derives, of its nature, from the call to holiness” (Address of May 15, 1998). At the same time, holiness is the ultimate goal of the Church’s activities. For this reason, “all pastoral initiatives must be set in relation to holiness” (Novo Millennio Ineunte, 30). “[I]n the life of the Church every call to action is a call to holiness” (Address of May 3, 1984).

“Now, no less than in the past, the call to holiness must be the chief concern of all the Church’s members” (Ad limina address of May 26, 1992). This is the primary way of participation in the life and mission of the Church, the foundation for every other vocation, without which ecclesiastical activity is deprived of its vital principle. Holiness is the key to the New Evangelization.

Evangelization in the third millennium must come to grips with the urgent need for a presentation of the Gospel message which is dynamic, complete, and demanding. The Christian life to be aimed at cannot be reduced to a mediocre commitment to “goodness” as society defines it; it must be a true quest for holiness. We need to re-read with fresh enthusiasm the fifth chapter of Lumen Gentium, which deals with the universal call to holiness. Being a Christian means to receive a “gift” of sanctifying grace which cannot fail to become a “commitment” to respond personally to that gift in everyday life. It is precisely for this reason that I have sought over the years to foster a wider recognition of holiness, in all the contexts where it has appeared, so that Christians can have many different models of holiness, and all can be reminded that they are personally called to this goal. (Letter to Priests, Mar 25, 2001)

Meditations on the saints

An often-overlooked aspect of Pope St. John Paul II’s pontificate is the numerous apostolic letters he wrote on the saints:

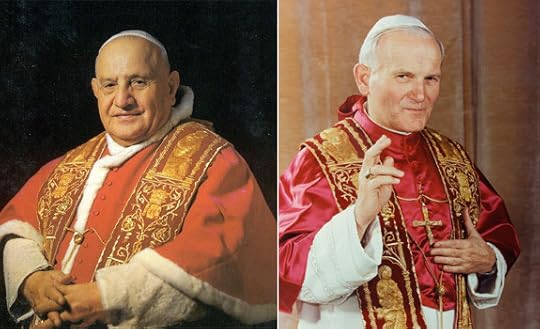

Two Saintly Popes: How John Paul II and John XXIII Modeled Virtue

by Fr. Robert Barron | CWR blog

This Sunday, Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli (Pope John XXIII) and Karol Jozef Wojtyla (Pope John Paul II) will be recognized as saints of the Catholic Church, and may God be praised for it! No one with the slightest amount of historical sensibility would doubt that these men were figures of enormous significance and truly global impact. But being a world historical personage is not the same as being a saint; otherwise neither Therese of Lisieux, nor John Vianney, nor Benedict Joseph Labre would be saints. So what is it that made these two men worthy particularly of canonization, of being “raised to the altars” throughout the Catholic world?

Happily, the Church provides rather clear and objective criteria for answering this question. A saint is someone who lived a life of “heroic virtue” on earth and who is now living the fullness of God’s life in heaven. In order to determine the second state of affairs, the Church rigorously tests claims that a miracle was worked through the revered person’s intercession. It would be the stuff of another article to examine these processes in regard to the two Popes under consideration: both are, in fact, fascinating. But for now I want to focus on the extraordinary virtues that these two men possessed, moral and spiritual qualities so striking that they are proposed to all for emulation.

When the Church speaks of the virtues, it is referring to the cardinal virtues of justice, prudence, temperance, and courage, as well as the theological virtues of faith, hope, and love. It wouldn’t be possible, within the brief scope of this article, to examine our two new saints in regard to all seven of the virtues, but let us make at least a beginning.

April 22, 2014

The “Green Pope” and a Human Ecology

The “Green Pope” and a Human Ecology | William Patenaude | CWR

A new collection of Benedict XVI’s eco-centric homilies, letters, and addresses offers much to ponder and perhaps even act on

It’s a joy to happen upon an old friend, to again hear their style of speaking and their way of engaging the world. When the old friend is Benedict XVI, however, things quickly move beyond the sentimental. So it goes with The Garden of God: Toward a Human Ecology (The Catholic University of America Press, 2014), a helpful compilation of Benedict XVI’s many, many statements about preserving life on earth.

Given that discussions of ecology polarize a great many along worldly ideological fault lines, one of the benefits of The Garden of God is in remembering how Benedict XVI, like his predecessor, normalized the topic and maintained it within Catholic orthodoxy. Like no other, he taught us how the Christian creed speaks to an array of social and physical sciences that are concerned with relationships, life, and shared futures.

The timing of this book is particularly good. Of late, environmental scientists are escalating their individual warnings. And the month of April finds a great many Earth Day celebrations taking place across the globe. With the help of The Garden of God, Catholics can better engage the ecological movement by discerning what we share with other environmental advocates and what we don’t.

To help, the publishers have chosen three themes to bring together 51 of Benedict XVI’s eco-centric homilies, letters, audiences, speeches, talks, angelus addresses, and much more (including a conversation with astronauts aboard the International Space Station). These themes are “Creation and Nature,” “The Environment, Science, and Technology,” and “Hunger, Poverty, and the Earth’s Resources.”

While these groupings are helpful, there are other ways to parse the ecological thought of Benedict XVI, especially for those who appreciate the former pontiff but may not feel the same way about the mainstream expression of ecological advocacy, or for those who consider themselves environmentalists but may be wary of Benedict XVI based on puerile narratives about Joseph Ratzinger that are still present in secular and some Catholic circles.

A second way to organize Benedict XVI’s eco-statements is provided by Archbishop Jean-Louis Bruges in the book’s foreword. And elsewhere, a recent pastoral letter on ecology by Bishop Dominique Rey of the Diocese of Fréjus-Toulon, France, offers additional insights into what Benedict XVI has given the Church.

But before plunging into the theological and anthropological depths of Benedict XVI’s ecological corpus, it helps to consider why he stressed environmental protection so often in the first place.

April 21, 2014

An Interview with Michael Nicholas Richard, author of "Tobit's Dog"

by Meryl Amland | IPNovels.com

Michael Nicholas Richard is the author of the Ignatius Press novel Tobit’s Dog. He has also written another novel, Bogfoke, and a few published short stories, one of which can be found in the anthology Heroic Visions II. Michael also enjoys writing for his blog. Michael lives near New Bern, NC with his wife and two dogs. Ignatius Press Novels interviewed him via email.

From where did the inspiration for Tobit’s Dog originate?

Richard: I have always been a dog person. When my mother was pregnant with me, my parents had a dog, Sam, of which they were very fond. He was a peculiar dog and my paternal grandmother thought they treated him too much like a human being. She warned, “You’re going to mark that baby.” Her suspicions were evidently confirmed when as a toddler I developed the habit of hiding raw carrots and then later bringing them out, shriveled, to chew on.

So my credentials as a dog person go back to the beginning of my personhood. Sometime in 2012 the notion that became Tobit’s Dog was stirred by the very presence of a dog in the Book of Tobit. The presence of a dog was one of the factors that led to canonicity of the Book of Tobit being challenged, since dogs were seen as “unclean” in Semitic cultures. It is only mentioned twice, once when Tobias leaves, and when he returns home. That unexpected element of the story got this dog person to pondering.

The pondering grew, until I realized I had to write it out. Originally I intended to set the story in Persia and to keep it closer to the Biblical story, but it occurred to me that there were some parallels between the plight of exiled Jews in the Biblical story, and the plight of African-Americans in the Jim Crow South. From there it just took off. I set aside the novel I was working on (it was about ready for a cool down period anyway) and started working on Tobit’s Dog. Making Tobit and his family African-American Catholics in the Jim Crow era added another layer of prejudice and isolation as well as offering a platform for Catholic themes.

I sent the manuscript for Tobit’s Dog to Ignatius Press the Monday before the Martin Luther King, Jr. holiday. The following Sunday one of our deacons, Rick Fisher, himself an African-American, gave a brief talk and reading concerning Dr. King before Mass. It was not lost on me, of course, that having mailed off the manuscript earlier that week, here I was listening to an African-American Catholic speaking on the plight of African-Americans during the Civil Rights era.

It became down right “spooky” for me as in the six months that followed the Book of Tobit became featured in the readings at Mass. I attend Mass on a near daily basis and it was a reading from the Book of Tobit or of the Canticle of Tobit nearly every day until the time I received an email from Ignatius Press expressing a desire to publish Tobit’s Dog.

I often read of strange “coincidences” in the lives of converts and reverts and people in spiritual struggle, and have thought, “Well, yeah, it’s easy to believe if God gives you all those signs!” Well, there it was for me. Not that the Father of Lies doesn’t still try to whisper into the back of my mind so that I might squirm out of that revelation—because, as Ace Redbone says to Lenny Morris in Tobit’s Dog, “To whom much is given, much is expected”—but it’s like Deacon Fisher said to me only a few days ago, “There are no coincidences with God.”

Is this your first novel?

Balthasar, his Christology, and the Mystery of Easter

Balthasar, his Christology, and the Mystery of Easter | Aidan Nichols OP | Introduction to Hans Urs von Balthasar's Mysterium Paschale

Balthasar was born in Lucerne in 1905. [1] It is probably significant that he was born in that particular Swiss city, whose name is virtually synonymous with Catholicism in Swiss history. The centre of resistance to the Reformation in the sixteenth century, in the nineteenth it led the Catholic cantons in what was virtually a civil war of religion, the War of the Sonderbund (which they lost). Even today it is very much a city of churches, of religious frescoes, of bells. Balthasar is a very self-consciously Catholic author. He was educated by both Benedictines and Jesuits, and then in 1923 began a university education divided between four  Universities: Munich, Vienna, Berlin — where he heard Romano Guardini, for whom a Chair of Catholic Philosophy had been created in the heartland of Prussian Protestantism [2] - and finally Zurich.

Universities: Munich, Vienna, Berlin — where he heard Romano Guardini, for whom a Chair of Catholic Philosophy had been created in the heartland of Prussian Protestantism [2] - and finally Zurich.

In 1929 he presented his doctoral thesis, which had as a subject the idea of the end of the world in modern German literature, from Lessing to Ernst Bloch. Judging by his citations, Balthasar continued to regard playwrights, poets and novelists as theological sources as important as the Fathers of the Schoolmen. [3] He was prodigiously well-read in the literature of half a dozen languages and has been called the most cultivated man of his age. [4] In the year he got his doctorate, he entered the Society of Jesus. His studies with the German Jesuits he described later as a time spent languishing in a desert, even though one of his teachers was the outstanding Neo-Scholastic Erich Przywara, to whom he remained devoted. [5] From the Ignatian Exercises he took the personal ideal of uncompromising faithfulness to Christ the Word in the midst of a secular world. [6] His real theological awakening, however, only happened when he was sent to the French Jesuit study house at Lyons, where he found awaiting him Henri de Lubac and Jean Daniélou, both later to be cardinals of the Roman church. These were the men most closely associated with the 'Nouvelle Théologie', later to be excoriated by Pope Pius XII for its patristic absorption. [7] Pius XII saw in the return to the Fathers two undesirable hidden motives. These were, firstly, the search for a lost common ground with Orthodoxy and the Reformation, and secondly, the desire for a relatively undeveloped theology which could then be presented in a myriad new masks to modern man. [8] The orientation to the Fathers, especially the Greek Fathers, which de Lubac in particular gave Balthasar did not, in fact, diminish his respect for historic Scholasticism at the level of philosophical theology. [9] His own metaphysics consist of a repristinated Scholasticism, but he combined this with an enthusiasm for the more speculative of the Fathers, admired for the depths of their theological thought as well as for their ability to re-express an inherited faith in ways their contemporaries found immediately attractive and compelling. [10]

Balthasar did not stay with the Jesuits. In 1940 they had sent him to Basle as a chaplain to the University. From across the Swiss border, Balthasar could observe the unfolding of the Third Reich, whose ideology he believed to be a distorted form of Christian apocalyptic and the fulfilment of his own youthful ideas about the rôle of the eschatology theme in the German imagination. While in Basle Balthasar also observed Adrienne von Speyr, a convert to Catholicism and a visionary who was to write an ecstatic commentary on the Fourth Gospel, and some briefer commentaries on other New Testament books, as well as theological essays of a more sober kind. [11] In 1947, the motu proprio Provida Mater Ecciesia created the possibility of 'secular institutes' within the Roman Catholic Church, and, believing that these Weltgemeinschaften of laity in vows represented the Ignatian vision in the modern world, Balthasar proposed to his superiors that he and Adrienne von Speyr together might found such an institute within the Society of Jesus. When they declined, he left the Society and in 1950 became a diocesan priest under the bishop of Chur, in eastern Switzerland. Soon Balthasar had published so much that he was able to survive on his earnings alone, and moved to Einsiedeln, not far from Lucerne, where, in the shadow of the venerable Benedictine abbey, he built up his publishing house, the Johannes Verlag, named after Adrienne von Speyr's preferred evangelist. She died in 1967, but he continued to regard her as the great inspiration of his life, humanly speaking.

In 1969 Balthasar was appointed by Pope Paul VI to the International Theological Commission, and, after that date, he was drawn increasingly into the service of the Church's teaching office. In 1984, Pope John Paul II symbolized his high regard for Balthasar by awarding him the Paul VI prize for his services to theology. These included not only the unbroken stream of his own writing, but his founding, in 1972, of the international Catholic review Communio — a critical sifting, in the light of theological tradition, of the abundant but often confusing wares made available by post-conciliar Catholicism. Balthasar died in Basle on 26 June 1988, three days before his investiture as a cardinal of the Roman church. His remains are buried in the family grave, under the cloister of Lucerne cathedral.

Balthasar's writings are formidable in number and length. Any one area of his publications would constitute a decent life's work for a lesser man. In patristics he wrote accounts of Origen, Gregory of Nyssa and Maximus the Confessor. [12] In literature, he produced a major study of Bernanos [13] as well as translations of Claudel, Péguy and Calderón. In philosophy he turned his thesis into three massive tomes under the title Apokalypse der deutchen Seele, [14] from Lessing through Nietzsche to the rise of Hitler. Although a major idea of this work is the notion that the figure of Christ remained a dominant motif in German Romanticism, more significant for Balthasar's later Christology is his essay Wahrheit: Die Wahrheit der Welt, [15] in which he argues that the great forgotten theme of metaphysics is the theme of beauty.

Balthasar presents the beautiful as the 'forgotten transcendental', pulchrum, an aspect of everything and anything as important as verum, 'the true', and bonum, 'the good'. The beautiful is the radiance which something gives off simply because it is something, because it exists. A sequel to this work, intended to show the theological application of its leading idea, was not written until forty years later but Balthasar had given clear hints as to what it would contain. What corresponds theologically to beauty is God's glory. The radiance that shows itself through the communicative forms of finite being is what arouses our sense of transcendence, and so ultimately founds our theology. Thus Balthasar hit upon his key theological concept, as vital to him as ens a se to Thomists or 'radical infinity' to Scotists. In significant form and its attractive power, the Infinite discloses itself in finite expression, and this is supremely true in the biblical revelation. Thus Balthasar set out on his great trilogy: a theological aesthetics, [16] concerned with the perception of God's self-manifestation; a theological dramatics, [17] concerned with the content of this perception, namely God's action towards man; and a theological logic [18] dealing with the method, at once divine and human, whereby this action is expressed.

Balthasar insisted, however, that the manner in which theology is to be written is Christological from start to finish. He defined theology as a mediation between faith and revelation in which the Infinite, when fully expressed in the finite, i.e. made accessible as man, can only be apprehended by a convergent movement from the side of the finite, i.e. adoring, obedient faith in the God-man. Only thus can theology be Ignatian and produce 'holy worldliness', in Christian practice, testimony and self-abandonment. [19] Balthasar aimed at nothing less that a Christocentric revolution in Catholic theology. It is absolutely certain that the inspiration for this, derives, ironically for such an ultra- Catholic author, from the Protestantism of Karl Barth.

In the 1940s Balthasar was not the only person interested in theology in the University of Basle. Balthasar's book on Barth, [20] regarded by some Barthians as the best book on Barth ever written, [21] while expressing reserves on Barth's account of nature, predestination and the concept of the Church, puts Barth's Christocentricity at the top of the list of the things Catholic theology can learn from the Church Dogmatics. [22] Not repudiating the teaching of the First Vatican Council on the possibility of a natural knowledge of God, Balthasar set out nevertheless to realize in Catholicism the kind of Christocentric revolution Barth had wrought in Protestantism: to make Christ, in Pascal's words, 'the centre, towards which all things tend'. [23] Balthasar's acerbity towards the Catholic theological scene under Paul VI derived from the sense that this overdue revolution was being resisted from several quarters: from those who used philosophical or scientific concepts in a way that could not but dilute Christocentrism, building on German Idealism (Karl Rahner), evolutionism (Teilhard de Chardin) or Marxism (liberation theology), and from those who frittered away Christian energies on aspects of Church structure or tactics of pastoral practice, the characteristic post-conciliar obsessions. [24]

In his person, life, death and resurrection, Jesus Christ is the 'form of God'. As presented in the New Testament writings, the words, actions and sufferings of Jesus form an aesthetic unity, held together by the 'style' of unconditional love. Love is always beautiful, because it expresses the self- diffusiveness of being, and so is touched by being's radiance, the pulchrum. But the unconditional, gracious, sacrificial love of Jesus Christ expresses not just the mystery of being — finite being — but the mystery of the Source of being, the transcendent communion of love which we call the Trinity. [25] Thus through the Gestalt Christi, the love which God is shines through to the world. This is Balthasar's basic intuition.

The word 'intuition' is, perhaps, a fair one. Balthasar is not a New Testament scholar, not even a (largely) self-taught one like Schillebeeckx. Nor does he make, by Schillebeeckx's exigent standards, a very serious attempt to incorporate modern exegetical studies into his Christology. His somewhat negative attitude towards much — but, as Mysterium Paschale shows, by no means all — of current New Testament study follows from his belief that the identification of ever more sub-structures, redactional frameworks, 'traditions', perikopai, binary correspondences, and other methodological items in the paraphernalia of gospel criticism, tears into fragments what is an obvious unity. The New Testament is a unity because the men who wrote it had all been bowled over by the same thing, the glory of God in the face of Christ. Thus Balthasar can say, provocatively, that New Testament science is not a science at all compared with the traditional exegesis which preceded it. To be a science you must have a method adequate to your object. Only the contemplative reading of the New Testament is adequate to the glory of God in Jesus Christ. [26]

The importance of the concept of contemplation for Balthasar's approach to Christ can be seen by comparing his view of perceiving God in Christ with the notion of looking at a painting and seeing what the artist has been doing in it. [27] In Christian faith, the captivating force (the 'subjective evidence') of the artwork which is Christ takes hold of our imaginative powers; we enter into the 'painterly world' which this discloses and, entranced by what we see, come to contemplate the glory of sovereign love of God in Christ (the 'objective evidence') as manifested in the concrete events of his life, death and resurrection. [28] So entering his glory, we become absorbed by it, but this very absorption sends us out into the world in sacrificial love like that of Jesus.

This is the foundation of Balthasar's Christology, but its content is a series of meditations on the mysteries of the life of Jesus. His Christology is highly concrete and has been compared, suggestively, to the iconography of Andrei Rublev and Georges Roualt. [29] Balthasar is not especially concerned with the ontological make-up of Christ, with the hypostatic union and its implications, except insofar as these are directly involved in an account of the mysteries of the life. [30] In each major moment ('mystery') of the life, we see some aspect of the total Gestalt Christi, and through this the Gestalt Gottes itself. Although Balthasar stresses the narrative unity of these episodes, which is founded on the obedience that takes the divine Son from incarnation to passion, an obedience which translates his inner-Trinitarian being as the Logos, filial responsiveness to the Father, [31] his principal interest — nowhere more eloquently expressed than in the present work — is located very firmly in an unusual place. This place is the mystery of Christ's Descent into Hell, which Balthasar explicitly calls the centre of all Christology. [32] Because the Descent is the final point reached by the Kenosis, and the Kenosis is the supreme expression of the inner-Trinitarian love, the Christ of Holy Saturday is the consummate icon of what God is like. [33] While not relegating the Crucifixion to a mere prelude — far from it! — Balthasar sees the One who was raised at Easter as not primarily the Crucified, but rather the One who for us went down into Hell. The 'active' Passion of Good Friday is not, at any rate, complete without the 'passive' Passion of Holy Saturday which was its sequel.

Balthasar's account of the Descent is indebted to the visionary experiences of Adrienne von Speyr, and is a world away from the concept of a triumphant preaching to the just which nearly all traditional accounts of the going down to Hell come under. [34] Balthasar stresses Christ's solidarity with the dead, his passivity, his finding himself in a situation of total self-estrangement and alienation from the Father. For Balthasar, the Descent 'solves' the problem of theodicy, by showing us the conditions on which God accepted our foreknown abuse of freedom: namely, his own plan to take to himself our self-damnation in Hell. It also demonstrates the costliness of our redemption: the divine Son underwent the experience of Godlessness. Finally, it shows that the God revealed by the Redeemer is a Trinity. Only if the Spirit, as vinculum amoris between the Father and the Son, can re-relate Father and Son in their estrangement in the Descent, can the unity of the Revealed and Revealer be maintained. In this final humiliation of the forma servi, the glorious forma Dei shines forth via its lowest pitch of self-giving love.

Mysterium Paschale could not, however, be an account of the paschal mystery, the mystery of Easter, unless it moved on, following the fate of the Crucified himself, to the Father's acceptance of his sacrifice, which we call the Resurrection. Whilst not over-playing the role of the empty tomb — which is, after all, a sign, with the limitations which that word implies, Balthasar insists, in a fashion highly pertinent to a recurrent debate in England, as well as in Continental Europe, that the Father in raising the Son does not go back on the Incarnation: that is, he raises the Son into visibility, rather than returns him to the pre-incarnate condition of the invisible Word. The Resurrection appearances are not visionary experiences but personal encounters, even though the Resurrection itself cannot be adequately thought by means of any concept, any comparison.

Finally, in his account of the 'typical' significance of such diverse Resurrection witnesses as Peter, John and the women, Balthasar offers a profound interpretation of the make-up of the Church, which issued from the paschal mystery of Christ. In his portrayal of the inter-relation of the masculine and feminine elements in the community of the Crucified and Risen One — the Church of office and the Church of love, Balthasar confirms the words spoken in his funeral oration by Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger:

Balthasar had a great respect for the primacy of Peter, and the hierarchical structure of the Church. But he also knew that the Church is not only that, nor is that what is deepest in the Church. [35]

What is deepest in the Church, as the concluding section of Mysterium Paschale shows, is the spouse-like responsiveness of receptivity and obedience to the Jesus Christ who, as the Church's Head, 'ever plunges anew into his own being those whom he sends out as his disciples'.

REFERENCES:

[1] Balthasar's own estimate of his life and work is in Rechenschaft (Einsiedeln 1965). The most thorough study of his theology to date is A. Moda, Hans Urs von Balthasar (Ban 1976); for his Christology see also G. Marchesi, La Cristologia di Hans Urs von Balthasar (Rome 1977).

[2] See H. U. von Balthasar, Romano Guardini. Reform aus dem Ursprung (Munich 1970): the title is significant.

[3] See especially, Herrlichkeit. Em theologische Ästhetik (Einsiedeln 1961-1969), Ill/I. Et: The Glory of God (Edinburgh and San Francisco 1983-).

[4] By H. de Lubac in 'Un testimonio di Cristo. Hans Urs von Balthasar', Humanitas 20 (1965) p. 853.

[5] H. U. von Balthasar 'Die Metaphysik Erich Pyrzwara', Schweizer Rundschau 33 (1933), pp. 488-499. Przywara convinced him of the importance of the analogy of being in theology.

[6] Balthasar has compared the 'evangelicalism' of the Exercises to that not only of Barth but of Luther. See Rechenschaft, op. cit., pp. 7-8.

[7] See R. Aubert's summary of the Nouvelle Théologie in Bilan de la théologie du vingtième siècle (Paris 1971), I. pp. 457-460.

[8] Pius XII, Humani Generis 14-17.

[9] Stressed by B. Mondin, 'Hans Urs von Balthasar e l'estetica teologica' in I grandi teologi del secolo ventesimo I (Turin 1969), pp. 268-9.

[10] De Lubac spoke of Balthasar enjoying 'una specie di connaturalità' with the Fathers; but he has never suffered from that tiresome suspension of all criticism of patristic theology which is sometimes found, not least in England. In Liturgie Cosmique: Maxime le Confesseur (Paris 1947) he points out that the Fathers stand at the beginning (only) of Christian thought, pp. 7-8.

[11] H. U. von Balthasar, Erster Blick auf Adrienne von Speyr (Einsiedeln 1967), with full bibliography.

[12] Parole et mystère chez Origène (Paris 1957); Presence et pensée. Essai sur la philosophie religieuse de Grégoire de Nysse (Paris 1942); Kosmische Liturgie. Höhe und Krise des griechischen Weltbilds bei Maximus Confessor (Freiburg 1941).

[13] Bernanos (Cologne 1954).

[14] Apokalypse der deutschen Seele (Salzburg 1937-9).

[15] Wahrheit. Wahrheit der Welt (Einsiedeln 1947).

[16] Thus Herrlichkeit, op. cit.

[17] Theodramatik (Einsiedeln 1973-6).

[18] The Theologik took up the earlier Wahrheit. Wahrheit der Welt, op. cit., re-published as Theologik I, and united it to a new work, Wahrheit Gottes. Theologik II. Both appeared at Einsiedeln in 1985. Also relevant to this project is his Das Ganze im Fragment (Einsiedeln 1963).

[19] 'Der Ort der Theologie', Verbum Caro (Einsiedeln 1960).

[20] Karl Barth. Darstellung und Deutung seiner Theologie (Cologne 1951).

[21] By Professor T. F. Torrance, to the present author in a private conversation.

[22] op. cit. pp. 335-372.

[23] Pensées 449 in the Lafuma numbering.

[24] See Schleifung der Bastionen (Einsiedeln 1952); Wer ist ein Christ? (Einsiedeln 1965); Cordula oder der Ernstfall (Einsiedeln 1966). The notion that, because Christian existence has its own form, which is founded on the prior form of Christ, Christian proclamation does not (strictly speaking) need philosophical or social scientific mediations, is the clearest link between Balthasar and Pope John Paul II. See, for instance, the papal address to the South American bishops at Puebla.

[25] Herrlichkeit I pp. 123-658.

[26] Einfaltungen. Auf Wegen christlicher Einigung (Munich 1969).

[27] Cf. A. Nichols OP, The Art of God Incarnate (London 1980), pp. 105-152.

[28] For an excellent analysis of Balthasar's twofold Christological 'evidence', see A. Moda, op. cit., pp. 305-410.

[29] By H. Vorgrimler, in Bilan de la Théologie du vingtième siècle, op. cit., pp. 686ff.

[30] We can say that, had Balthasar been St Thomas, he would have begun the Tertia pars of the Summa at Question 36: de manfestatione Christ nati.

[31] 'Mysterium Paschale', in Mysterium Salutis III/2 (Einsiedeln 1962), pp. 133-158.

[32] Glaubhaft ist nur Liebe (Einsiedeln 1963), p. 57.

[33] 'Mysterium Paschale', art. cit., pp. 227-255. Balthasar speaks of a 'contemplative Holy Saturday' as the centre of theology, in contra-distinction to G. W. F. Hegel's 'speculative Good Friday'.

[34] See J. Chaine, 'La Descente du Christ aux enfers', Dictionnaire de la Bible, Supplément II.

[35] Translated from the French, alone accessible to me, of Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, 'Oraison funèbre de Hans-Urs von Balthasar', Communio XIV, 2 (March-April 1989), p. 8.

The translator is grateful to the editor of New Blackfriars for permission to re-publish, in modified form, some material originally found in that journal (66.781-2 [1985]) as 'Balthasar and his Christology'.

Excerpts from the writings of Hans Urs von Balthasar:

• Introduction | From Adrienne von Speyr's The Book of All Saints

• The Conquest of the Bride | From Heart of the World

• Jesus Is Catholic | From In The Fullness of Faith: On the Centrality of the Distinctively Catholic

• A Résumé of My Thought | From Hans Urs von Balthasar: His Life and Work

• Church Authority and the Petrine Element | From In The Fullness of Faith: On the Centrality of the Distinctively Catholic

• The Cross–For Us | From A Short Primer For Unsettled Laymen

• A Theology of Anxiety? | The Introduction to The Christian and Anxiety

• "Conceived by the Holy Spirit, born of the Virgin Mary" | From Credo: Meditations on the Apostles' Creed

IgnatiusInsight.com articles about Hans Urs von Balthasar:

• Discerning What Is Christian | The Foreword to Hans Urs von Balthasar's Engagement with God | Margaret M. Turek

• Hans Urs von Balthasar and the Tarot | Stratford Caldecott

• Love Alone is Believable: Hans Urs von Balthasar’s Apologetics | Fr. John R. Cihak

• Balthasar and Anxiety: Methodological and Phenomenological Considerations | Fr. John R. Cihak

• Reading von Balthasar Together: An Interview with Adam Janke | Carl E. Olson

Fr. Aidan Nichols, O.P., a Dominican priest, is currently the John Paul II Memorial Visiting Lecturer, University of Oxford; has served as the Robert Randall Distinguished Professor in Christian Culture, Providence College; and is a Fellow of Greyfriars, Oxford. He has also served as the Prior of the Dominicans at St. Michael's Priory, Cambridge. Father Nichols is the author of numerous books including Looking at the Liturgy, Holy Eucharist, Hopkins: Theologian's Poet, and The Thought of Benedict XVI. His most recent book is Lovely Like Jerusalem: The Fulfillment of the Old Testament in Christ and the Church.

Carl E. Olson's Blog

- Carl E. Olson's profile

- 20 followers