Carl E. Olson's Blog, page 98

May 4, 2014

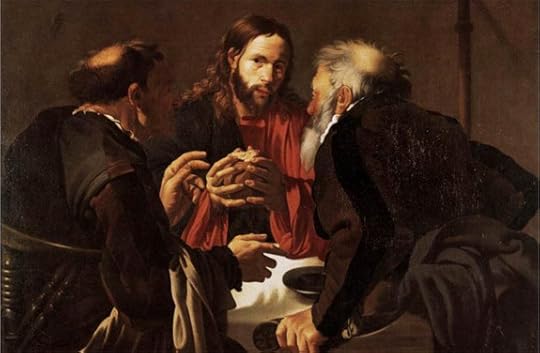

The Road to Emmaus, The Reality of the Eucharist

"Supper at Emmaus" (c. 1621) by Hendrick Terbrugghen

A Scriptural Reflection the Readings for Sunday, May 4, 2014, the Third Sunday of Easter | Carl E. Olson

Readings:

• Acts 2:14, 22-33

• Psa. 16:1-2, 5, 7-8, 9-10, 11

• 1 Pet. 1:17-21

• Lk. 24:13-25

I grew up attending a small Fundamentalist Bible chapel that believed the Lord’s Supper should be commemorated each week. Nearly every Sunday we took time to contemplate the death of Jesus Christ by quietly reflecting on the Cross and partaking of bread and grape juice.

It was not, of course, the Eucharist. But it was, in hindsight, an action that pointed me, however imperfectly, to the Eucharist and the Catholic Church. Today’s Gospel reading, one of my favorite passages from the Gospel of Luke, beautifully shows the relationship between the supernatural gift of faith and Holy Communion.

Luke, a masterful storyteller, incisively describes how the disciples had completely lost their bearings and sense of spiritual direction in the overwhelming aftermath of Jesus’ death: “They stopped, looking downcast” (Lk. 24:17). Approached by Jesus, they failed recognize their Lord. Responding to His question about their conversation, the men explained their confusion: Jesus was “a prophet mighty in deed and word” and yet He had not fulfilled their hope for redemption (v. 21). In addition to this disappointment there was the added mystery of the empty tomb, although they apparently hadn’t reached a conclusion about what it might actually mean.

Jesus chided them and took them to the Scriptures, “beginning with Moses and with all the prophets”(v. 27), to show them the true nature of “the Christ.” There are several passages that Jesus likely showed them, including Deuteronomy 18:15, which promised “a prophet” like Moses, Psalm 2:7, a Messianic psalm, and Isaiah 53, which describes the Suffering Servant, as well as others. The disciples had to be shown that salvation and glory wouldn’t come through political might or social upheaval, but through humiliation, suffering, and apparent defeat.

Thus, on the road to Emmaus, there was a re-learning on the part of the disciples, who there heard a deeper explanation of the Scriptures they likely heard many times before. This was necessary in order for them to really grasp the significance of the Cross and its life-giving, soul-transforming meaning. This education came from the very One who sent the prophets and gave them words; who better than the Word Incarnate to illuminate the meaning of the sacred text? The narrative follows a distinct pattern of questioning, dialogue, and exposition of Scripture, leading to a sacrament, which is a pattern Luke uses again in the story of the Ethiopian eunuch (Acts 8).

Some commentators have suggested that the disciples finally recognized Jesus simply because of a familiar gesture on His part. But this understates how Luke purposefully uses the same description of Jesus’ actions—“he took bread, said a blessing, broke it, and gave it to them”—as he does in his account of the Last Supper (Lk 22:19-20). Yes, the disciples certainly recognized that gesture, but the recognition was a gift of grace, and it was intimately linked with the reality of the Eucharist. Which is why they later told the others how Christ “was made known to them in the breaking of bread.”

The story of the encounter on the road to Emmaus includes all of the essential elements of the Liturgy: Scripture, prayer, blessing, and the breaking of bread. The Catechism of the Catholic Church states that the “Eucharistic celebration always includes: the proclamation of the Word of God; thanksgiving to God the Father for all his benefits, above all the gift of his Son; the consecration of bread and wine; and participation in the liturgical banquet by receiving the Lord's body and blood.” These elements, it emphasizes, “constitute one single act of worship” (CCC 1408).

Every person hungers for this act of worship, for we were made to worship God in that way. God, in His goodness, responds to that hunger. In the midst of the disciples’ confusion and blindness, Jesus sought them out, offered Himself to them, and opened their eyes. He did it for me, many years ago. He wishes to meet all of us on our road to Emmaus.

(This "Opening the Word" column originally appeared in the April 6, 2008, edition of Our Sunday Visitor newspaper.)

May 1, 2014

Islam and Jesus, Son of Mary

The name "Jesus son of Mary" written in Islamic calligraphy followed by "Peace be upon him" (Wikipedia Commons)

Islam and Jesus, Son of Mary | William Kilpatrick | CWR

Holy Trinity Catholic Church in Syracuse, New York, will soon be The Mosque of Jesus, Son of Mary

Holy Trinity Catholic Church in Syracuse, New York, was sold in December to a Muslim group and will be turned into a mosque. The Muslim organization requested that six stone crosses be removed from the top of the century-old historic church, and the Syracuse Landmark Preservation Board has complied. However, as Syracuse.com explains in an April 6, 2014 article, “Plans to turn a church into a mosque bring pain and hope to changing neighborhood”, everything evens out because the mosque will be named the Mosque of Jesus, Son of Mary “to build a bridge between the old and the new”.

So that’s all right then. Or is it? The news story is written to the theme that Islam and Catholicism share much in common—two sides of the same coin, so to speak. A diocesan spokeswoman is quoted as saying that “the building is once again being used to meet the needs of a growing population on the North Side, just as Holy Trinity did as it served the Catholic faithful.” In this telling, immigrant Muslims are just like immigrant Catholics of a hundred years ago. After all, both believe in Jesus, the son of Mary. “The Muslims could not keep the crosses on the church,” the Syracuse.com report concludes, “But they chose the mosque's name to build a bridge between the old and the new: The Mosque of Jesus, Son of Mary.”

Why do the crosses have to come down? The reason, as explained by one of the Muslim organizers, is that “crosses are not an appropriate representation of the religion of Islam.” Why is that? Because the Koran maintains that Jesus was never crucified and therefore never rose from the dead (4:157).

In short, there are reasons to wonder if the Jesus, son of Mary that Muslims revere is the same Jesus that Christians revere.

April 30, 2014

What Is Your Crutch?

What Is Your Crutch? | Thomas M. Doran | CWR blog

The question is not whether a person has a crutch, but whether it is constructed of straw, of false hardwood, or of genuine hardwood.

I once read an account of a student who challenged his teacher by stating that the teacher’s reliance on Christianity was a crutch. The teacher responded by admitting that Christ was his crutch, adding that he is a very good crutch, and then asking the student, “What is your crutch?”

One dictionary definition of crutch is, “Anything depended upon for support”.

As I’ve lived my own life, observed those around me, and read and heard about other lives, I have come to the conclusion that everyone has crutches, even those who project self-sufficiency. Some of these crutches are obvious; many are hidden from public view, with hidden crutches sometimes erupting into public scandals.

The question is not whether a person has a crutch, but whether this crutch is constructed of straw, of false hardwood, or of genuine hardwood.

Some crutches are known to be made of straw, even though many continue to rely on them: alcohol or food in excess; drugs; sexual compulsions and obsessions; greed to possess things and status; a long list.

Many insist they have no crutches. Often, atheists who reject belief in the existence of God claim that science and reason are their sole guides. These too are crutches. So, are they good crutches?

Other crutches on which people rely include the prominent “isms”: communism, nationalism, socialism, capitalism, epicureanism, stoicism, even feminism as an end in itself. Passionate cases have been made for each of these political, economic, and/or philosophical systems.

The problem with reliance on these “isms”, and even science, is that they are subject to human limitations, including the pervasive concupiscence that muddles and corrupts our thinking.

April 29, 2014

The opening pages of "Catherine of Siena" by Sigrid Undset

The opening pages of Catherine of Siena | by Sigrid Undset, the Nobel Prize winning author of Kristin Lavransdatter | Ignatius Insight

In the city-states of Tuscany the citizens—Popolani—businessmen, master craftsmen and the professional class had already in the Middle Ages demanded and won the right to take part in the government of the republic side by side with the nobles—the Gentiluomini. In Siena they had obtained a third of the seats in the High Council as early as the twelfth century. In spite of the fact that the different  parties and rival groups within the parties were in constant and often violent disagreement, and in spite of the frequent wars with Florence, Siena's neighbour and most powerful competitor, prosperity reigned within the city walls. The Sienese were rich and proud of their city, so they filled it with beautiful churches and public buildings. Masons, sculptors, painters and smiths who made the exquisite lattices and lamps, were seldom out of work. Life was like a brightly coloured tissue, where violence and vanity, greed and uninhibited desire for sensual pleasure, the longing for power, and ambition, were woven together in a multitude of patterns. But through the tissue ran silver threads of Christian charity, deep and genuine piety in the monasteries and among the good priests, among the brethren and sisters who had dedicated themselves to a life of helping their neighbours. The well-to-do and the common people had to the best of their ability provided for the sick, the poor and the lonely with unstinted generosity. In every class of the community there were good people who lived a quiet, modest and beautiful family life of purity and faith.

parties and rival groups within the parties were in constant and often violent disagreement, and in spite of the frequent wars with Florence, Siena's neighbour and most powerful competitor, prosperity reigned within the city walls. The Sienese were rich and proud of their city, so they filled it with beautiful churches and public buildings. Masons, sculptors, painters and smiths who made the exquisite lattices and lamps, were seldom out of work. Life was like a brightly coloured tissue, where violence and vanity, greed and uninhibited desire for sensual pleasure, the longing for power, and ambition, were woven together in a multitude of patterns. But through the tissue ran silver threads of Christian charity, deep and genuine piety in the monasteries and among the good priests, among the brethren and sisters who had dedicated themselves to a life of helping their neighbours. The well-to-do and the common people had to the best of their ability provided for the sick, the poor and the lonely with unstinted generosity. In every class of the community there were good people who lived a quiet, modest and beautiful family life of purity and faith.

The family of Jacopo Benincasa was one of these. By trade he was a wool-dyer, and he worked with his elder sons and apprentices while his wife, Lapa di Puccio di Piagente, firmly and surely ruled the large household, although her life was an almost unbroken cycle of pregnancy and childbirth—and almost half her children died while they were still quite small. It is uncertain how many of them grew up, but the names of thirteen children who lived are to be found on an old family tree of the Benincasas. Considering how terribly high the rate of infant mortality was at that time, Jacopo and Lapa were lucky in being able to bring up more than half the children they had brought into the world.

Jacopo Benincasa was a man of solid means when in 1346 he was able to rent a house in the Via dei Tintori, close to the Fonte Branda, one of the beautiful covered fountains which assured the town of a plentiful supply of fresh water. The old home of the Benincasas, which is still much as it was at that time, is, according to our ideas, a small house for such a big family. But in the Middle Ages people were not fussy about the question of housing, least of all the citizens of the fortified towns where people huddled together as best they could within the protection of the walls. Building space was expensive, and the city must have its open markets, churches and public buildings, which at any rate theoretically belonged to the entire population. The houses were crowded together in narrow, crooked streets. According to the ideas of that time the new home of the Benincasas was large and impressive.

Lapa had already had twenty-two children when she gave birth to twins, two little girls, on Annunciation Day, March 25, 1347. They were christened Catherine and Giovanna. Madonna Lapa could only nurse one of the twins herself, so little Giovanna was handed over to a nurse, while Catherine fed at her mother's breast. Never before had Monna Lapa been able to experience the joy of nursing her own children—a new pregnancy had always forced her to give her child over to another woman. But Catherine lived on her mother's milk until she was old enough to be weaned. It was all too natural that Lapa, who was already advanced in years, came to love this child with a demanding and well-meaning mother-love which later, when the child grew up, made the relationship between the good-hearted, simple Lapa and her young eagle of a daughter one long series of heart-rending misunderstandings. Lapa loved her immeasurably and understood her not at all.

Catherine remained the youngest and the darling of the whole family, for little Giovanna died in infancy, and a new Giovanna, born a few years later, soon followed her sister and namesake into the grave. Her parents consoled themselves with the firm belief that these small, innocent children had flown from their cradles straight into Paradise—while Catherine, as Raimondo of Capua writes, using a slightly far-fetched pun on her name and the Latin word "catena" (a chain), had to work hard on earth before she could take a whole chain of saved souls with her to heaven.

When the Blessed Raimondo of Capua collected material for his biography of St. Catherine he got Madonna Lapa to tell him about the saint's childhood—long, long ago, for Lapa was by that time a widow of eighty. From Raimondo's description one gets the impression that Lapa enjoyed telling everything that came into her head to such an understanding and responsive listener. She told of the old days when she was the active, busy mother in the middle of a flock of her own children, her nieces and nephews, grandchildren, friends and neighbours, and Catherine was the adored baby of a couple who were already elderly. Lapa described het husband Jacopo as a man of unparalleled goodness, piety and uprightness. Raimondo writes that Lapa herself "had not a sign of the vices which one finds among people of our time"; she was an innocent and simple soul, and completely without the ability to invent stories which were not true. But because she had the well-being of so many people on her shoulders, she could not be so unworldly and patient as her husband; or perhaps Jacopo was really almost too good for this world, so that his wife had to be even more practical than she already was, and on occasion she thought it her duty to utter a word or two of common sense to protect the interests of the family.

For Jacopo never said a hard or untimely word however upset or badly treated he might be, and if others in the house gave way to their bad temper or used bitter or unkind words he always tried to talk them round: "Now listen, for your own sake you must keep calm and not use such unseemly words." Once one of his townsmen tried to force him into paying a large sum of money which Jacopo did not owe him, and the honest dyer was hounded and persecuted till he was almost ruined by the slanderous talk of this man and his powerful friends. But in spite of everything Jacopo would not allow anyone to say a word against the man; Lapa did so, but her husband replied: "Leave him in peace, you will see that God will show him his fault and protect us." And a short while afrer that it really happened, said Lapa.

Coarse words and dirty talk were unknown in the dyer's home. His daughter Bonaventura, who was married to a young Sienese, Niccalo, was so much grieved when her husband and his friends engaged in loose talk and told doubtful jokes that she became physically ill and began to waste away. Her husband, who must really have been a well-meaning young man, was worried when he saw how thin and pale his bride was, and wanted to know what was wrong with her. Bonaventura replied seriously, "In my father's house I was not used to listening to such words as I must hear here every day. You can be sure that if such indecent talk continues in our house you will live to see me waste to death." Niccolo at once saw to it that all such bad habits which wounded his wife's feelings were stopped, and openly expressed his admiration for her chaste and modest ways, and the piety of his parents-in-law.

Such was the home of little Catherine. Everyone petted and loved her, and when she was still quite tiny her family admired her "wisdom" when they listened to her innocent prattle. And as she was also very pretty Lapa could scarcely ever have her to herself; all the neighbours wanted to borrow her! Medieval writers seldom trouble to describe children or try to understand them. But Lapa manages in a few pages of Raimondo's book to give us a picture of a little Italian girl, serious and yet happy, attractive and charming—and already beginning to show that overwhelming vitality and spiritual energy which many years later made Raimondo and her other "children" surrender to her influence, with the feeling that her words and her presence banished despondency and faint-heartedness, and filled their souls with the peace and love of God. As soon as she left the circle of her own family, little Catherine became the leader of all the other small children in the street. She taught them games which she had herself invented—that is to say innumerable small acts of devotion. When she was five years old she taught herself the Angelus, and she loved tepeating it incessantly. As she went up or down the stairs at home she used to kneel on each step and say an Ave Maria. For the pious little daughter of a pious family, where everyone talked kindly and politely to everyone else, it must have been quite natural for her as soon as she had heard of God to talk in the same way to Him and His following of saints. It was then still a kind of game for Catherine. But small children put their whole souls and all their imagination into their games.

The neighbours called her Euphrosyne. This is the name of one of the Graces, and it seemed that Raimondo had his doubts about it; could the good people in the Fontebranda quarter have such knowledge of classical mythology that they knew what the name meant? He thought that perhaps, before she could talk properly, Catherine called her something which the neighbors took to be Euphrosyne, for there is also a saint of that name. The Sienese were however used to seeing processions and listening to songs and verse, so they could easily have picked up more of the poets' property than Raimondo imagined. Thus for example, Lapa's father, Pucio de Piagnete, wrote verse in his free time; he was by trade a craftsman—a mattress maker. He was moreover a very pious man, generous towards the monasteries and to monks and nuns. He might easily have known both the heathen and the Christian Euphrosyne. Catherine was for a time very much interested in the legend of St. Euphrosyne, who is supposed to have dressed as a boy and run away from home to enter a monastery. She toyed with the idea of doing the same herself. . . .

Related IgnatiusInsight.com Book Excerpts:

• Chapter One of The Living Wood: Saint Helena and the Emperor Constantine (A Novel) | Louis de Wohl

• Chapter One of Citadel of God: A Novel About Saint Benedict | Louis de Wohl

Sigrid Undset (1882-1949), a renowned literary author and one of the most acclaimed novelists of the twentieth century, won the Nobel Prize for literature in 1928 for her epic work Kristin Lavransdatter.

Novel re-imagining of the biblical story of Tobit explores themes of faith, prejudice, and suffering

San Francisco, April 28, 2014 – The beautiful and timeless biblical story of Tobit is given a fresh new take in a recently released novel from Ignatius Press, Tobit’s Dog by Michael Nicholas Richard. Tobit’s Dog tells the story of a humble man named Tobit Messenger, who despite the ever-present oppression of the Jim Crow South around him, becomes a prosperous and well-respected man. One day forces beyond his control start a cascade of misfortune that leaves him blind and nearly destitute. It is then that an affable travelling musician, who calls himself Ace Redbone, shows up on his doorstep claiming to be a distant relative.

by Michael Nicholas Richard. Tobit’s Dog tells the story of a humble man named Tobit Messenger, who despite the ever-present oppression of the Jim Crow South around him, becomes a prosperous and well-respected man. One day forces beyond his control start a cascade of misfortune that leaves him blind and nearly destitute. It is then that an affable travelling musician, who calls himself Ace Redbone, shows up on his doorstep claiming to be a distant relative.

In an effort to alleviate his family’s dire situation, Tobit allows his son, Tobias, to accompany Ace Redbone on a quest to collect a long overdue debt. Together, Ace, Tobias, and a most peculiar dog named Okra set off on a journey that will lead to unexpected consequences. Currents of grace begin rippling through not only Tobit’s family but his entire community as hidden crimes are revealed and justice, which had almost been despaired of, is served.

This retelling of the biblical story of Tobit, set in North Carolina during the Depression, brings to life in surprising ways the beloved Old Testament characters, including the important but often overlooked family dog. In Tobit’s Dog, important themes such as faith, prejudice, and suffering are explored and the novel compels readers to ponder thought provoking questions about these important topics.

Author Michael Nicholas Richard explains why he decided to re-tell the classic biblical story, saying, “Language and our perception of reality are ever evolving and changing things. Even great truths can become stale in expression. We should always be seeking to express these truths in new ways. We risk losing some of each generation who cannot see the truth behind what feels, to them, to be tired clichés.”

Dr. Peter Kreeft, professor of philosophy at Boston College and author of the book Jacob’s Ladder, says, “Sheldon Vanauken, author of A Severe Mercy (which is indeed a masterpiece), gave me the best compliment I ever received from an author when he told me that one of my books was on his bookcase. He lived monastically in a one room cottage with one bookcase, and whenever he kept a new book he had to throw out an old one. If I were living in his house, Tobit’s Dog would be one of the books I’d keep, to read again in a few years. That applies to about 1 out of 100 of the books I read.”

Kreeft continues, “What’s so good about Tobit’s Dog? Richard’s transparent writing style gives us a charming story and a strong theme, with realistic, convincing characters that we care about, who exhibit genuine love and gentleness in a challenging culture. It’s a believable story whose characters we know are real from our own experience, even though they are mostly of another time. This book would make a great movie!”

James Casper, author of Everywhere in Chains, calls Tobit’s Dog “a sturdy tale in the journey genre, with hope, love, faithfulness, and spirituality wrapped into it. An ancient story retold and repopulated in a fresh and vibrant manner, it is a praiseworthy contribution to possibly America’s most unsung and yet important literary cultures, anchored in the fiction of Walker Percy and Flannery O’Connor.”

About the Author:

Michael Nicholas Richard lives with his wife, Sherri, in New Bern, North Carolina. He draws inspiration for most of his work from the historical graveyards, churches, and stories from his hometown. Michael has two grown daughters, two young grandchildren as well as two dogs. The dogs never ask for money, but the daughters and grandchildren don't shed. They are all allowed on the couch.

Richard is the author of the novel, Bogfoke, and a number of short stories in small press and mass market paperback formats.

Author Michael Nicholas Richard is available for interviews about this book. To request a review copy or an interview with Michael Nicholas Richard, please contact: Rose Trabbic, Publicist, Ignatius Press at (239)867-4180 or rose@ignatius.com

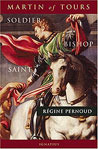

From Anti-Catholic Atheist to Church-Loving Convert

From Anti-Catholic Atheist to Church-Loving Convert | Catherine Harmon | CWR

“And what I saw was that the Church was right, and that nobody else was right—no one else on the face of the planet was speaking these truths.”

Jennifer Fulwiler is a popular Catholic blogger and homeschooling mother of six who writes about faith, family, media, and culture at her website, Conversion Diary. Fulwiler, whose memoir about her spiritual journey from atheism to Catholicism is titled Something Other Than God: How I Passionately Sought Happiness and Accidentally Found It and is available today from Ignatius Press, has been published in America, Our Sunday Visitor, Envoy, and National Review Online and has appeared on Fox and Friends and Life on the Rock. She was also the subject of the reality show Minor Revisions with Jennifer Fulwiler for New York’s NET TV. She recently spoke with Catholic World Report'smanaging editor Catherine Harmon about the new book, blogging through the process of conversion, and the personal challenges she faced when the practice of the Faith became more than an intellectual pursuit.

CWR: Let’s start with the title of your book, Something Other Than God. Where did the title come from and why did you choose it?

Jennifer Fulwiler: The title came from this wonderful C.S. Lewis quote, which is particularly meaningful because C.S. Lewis is also an atheist-to-Christian convert. The full quote says, “All that we call human history…is the long terrible story of man trying to find something other than God which will make him happy.” And the reason I chose that is because at first, I thought this story was just a standard conversion story, but as I got into the writing I realized this was more of a story of a search for happiness. So that’s why I chose that quote, because it talks about how we’re all searching for what will really make us happy, and we can only find that in God.

CWR: In the book you describe the very intense, almost arduous intellectual process you went through of coming to understand Christianity and what Christians believe. During that time what was your attitude toward “cradle Christians” or those who believed in Christ in a perhaps somewhat unreflective—or at least less intellectually rigorous—way?

Fulwiler: It changed over time. When I was younger, because I had had some bad experiences with Christians, I was very disdainful of “cradle believers” and just thought that they bought into these lies for self-serving reasons. As I got older, though, I began to see it as just a cultural thing. I didn’t think that people’s religion actually meant anything to them; I thought that’s what they did because it was the tradition in their family, or whatever.

CWR: At what point do you think your attitude started to change?

April 28, 2014

An Interview with Robert Ovies, author of "The Rising"

An Interview with Robert Ovies, author of The Rising | IPNovels.com

Robert Ovies is the author of the thrilling new novel The Rising, which tells the story of a young boy who mysteriously gains the ability to bring the dead back to life. He also maintains a website about the book. Ignatius Press Novels interviewed him via e-mail.

Is The Rising your first novel?

Ovies: Yes, it is. I’ve written about spiritual matters extensively and am writing two books along those lines now, but The Rising is my first novel.

It’s fascinating (and scary!) to think of all the implications of what rising from the dead would really be like. And that’s one of the things that really grabs the reader right away in “The Rising”. What kind of research did you do?

Ovies: My research has been grounded more in lived experiences than focused studies. I was a staff assistant at a funeral home, for example, a number of years ago, so I know those processes and procedures well. My daughter is Director of the Neuropsychology Department of the Illinois Neurological Institute (and author of a wonderful book for parents of special needs children) and was able to advise me relative to major hospital procedural issues in helpful detail. As a former advertising Creative Director, I’m very aware of the media and alert to its goals, tools and attention-oriented priorities. And, as a married deacon for thirty-eight years and former Director of Detroit’s Archdiocesan Offices for Family Life, Young Adult and Youth Ministries, I believe I’m well aware of church priorities and expectations across a wide range of issues. All of which, of course, have a direct bearing on the story being told in The Rising.

On a surface level, C.J., the young boy astonished by his ability to raise the dead, is the protagonist of “The Rising”. But it’s also about his parents, Lynn and Joe. And about his pastor, Father Mark. And then there are others—one of the strengths of the book is how the pivotal events in the story create tension in how each character reacts. How did you go about getting a handle on all of these characters?

Two Patron Saints of Christian Unity

A banner shows new Sts. John Paul II and John XXIII and Jesus during an April 28 Mass of thanksgiving for the canonizations of the new saints in St. Peter's Square at the Vatican. (CNS photo/Paul Haring)

Two Patron Saints of Christian Unity | Dr. Adam A. J. DeVille | CWR

John XXIII and John Paul II were responsible for historic advances in overcoming the problems of division and estrangement between Catholics, Orthodox, and Protestants

Regardless of what one thinks of Saints John XXIII and John Paul II, and prescinding from comment on certain aspects of their legacy as papal administrators, there is one outstanding feature of both popes that merits them a place in the pantheon of outstanding figures of our time: their deep and abiding desire to overcome the problem of division and estrangement between peoples, Christians above all.

It is difficult for many of us today to conceive of what relations between Christians were like even fifty years ago. I’ve spent more than a decade teaching undergraduates, and their knowledge of church history is even more abysmal than their knowledge of relatively recent history. Few of us can conceive of a time when Presbyterian pastors (as my grandmother saw first-hand) took to the streets in annual Orange parades to denounce the Catholic Church as the “whore of Babylon.” Few can remember when Catholic priests forbade their flocks from attending non-Catholic weddings. Few can remember the ringing denunciations (“heretics!” “schismatics!”) of each other, heard and uttered with some regularity.

The relatively friendly atmosphere that prevails today between almost all Christians, especially in North America, is the direct result of the Second Vatican Council called by “good Pope John.” While various ecumenical discussions were taking place between Catholics and Protestants prior to John XXIII's pontificate, the Council marked a most significant move forward, especially on the official level. The problem of Christian division was explicitly mentioned by Pope John XXIII in both announcing the council (see Humanae Salutis) and in his opening speech to its first session in 1962. Much of John’s concern for unity stemmed from his own background as nuncio in countries such as Bulgaria and Greece with huge Orthodox populations. His time in France, too, overlapped with a burgeoning Orthodox community in Paris (around l’Institut Saint-Serge), many of them refugees from the Bolshevik revolution and its persecution of Christians in the Soviet Union. He learned much from his interactions with Orthodox Christians, not least that they were in fact real Christians and not contumacious “schismatics.”

The council which John called would produce the landmark documents, Unitatis Redintegratio and Orientalium Ecclesiarum.

April 26, 2014

John XXIII, John Paul II, and the Quest for Peace in Africa

Pope John Paul II is assisted by South African President Nelson Mandela at the Johannesburg International Airport in 1995 at the start of the pope's first official visit to the country. (CNS photo/Patrick De Noirmont, Reuters)

John XXIII, John Paul II, and the Quest for Peace in Africa | Allen Ottaro | CWR blog

The two newest Saints have a deep history with Africa, and their teachings offer guidance today and for years to come

These past weeks leading up to the canonization of Blessed John XXIII and Blessed John Paul II, have provided a wonderful opportunity to revisit and reflect on their contribution to the Church and the world. This week , at the Pontifical Urban University in Rome, the Symposium of Episcopal Conferences of Africa and Madagascar (SECAM) organized a two-day event with the theme, “The Church in Africa: From the Second Vatican Council to the Third Millennium”. The conference was a chance to celebrate the contribution of the two Popes to the Church in the continent of Africa.

The two newest Saints have a deep history with Africa. While Pope Paul VI was the first pontiff in history to set foot on the continent when he visited Uganda in 1969, it was Pope John XIII who created the first African Cardinal, Laurean Rugambwa (1912-1997), in 1960. Pope John Paul II made numerous trips to Africa, including three visits to my own country, Kenya, within a span of fifteen years.

However, what has caught my attention, especially in light of recent and ongoing events on the African continent, is what I and my fellow African citizens can learn from these two great Saints as we seek to advance justice and peace.

During the month of April, Africa and the world have been commemorating the twentieth anniversary of the Rwandan genocide. The tragic events in Rwanda are still very fresh for many in the Central African country. The words “Never again” have been used repeatedly, in expressing the commitment that humanity will no longer remain as spectators in the face of the evil of war.

Regrettably, violence which has been described by various international agencies as “genocidal”, erupted late last year in the Central African Republic and South Sudan. And just this week, the world has witnessed what is being described as the “Massacre of Bentiu”, in which hundreds of civilians were killed in a church, a mosque and a hospital in the South Sudanese town of Bentiu.

The current conflict in South Sudan, pitting rebel forces under the command of former Vice President, Dr. Riek Machar, against government troops and President Salva Kiir, began in mid-December and was precipitated by internal power struggles within the ruling party, the Sudanese People Liberation Movement (SPLM). An agreement on the cessation of hostilities signed by the two parties and brokered by the Inter Governmental Authority on Development (IGAD) on the January 23rd, failed to hold, even after weeks of mediation talks in the Ethiopian capital, Addis Ababa. Watching a country—whose birth I was old enough to witness—disintegrate so soon, along with the human suffering, death and destruction being experienced, is a sad experience.

I recently turned to Pacem in Terris, the encyclical of Pope John XXIII on “Establishing Universal Peace in Truth, Justice, Charity and Liberty”, given on April 11, 1963. Now, the 1960s is significant in various ways in the history of the African continent, besides the many events in the life of the Church. More than thirty African countries gained independence during that period (1960-1969). A few weeks after Pacem in Terris was given, the Organization of African Unity (OAU), the predecessor to the African Union (AU) was formed, to promote unity and solidarity of African states in order to achieve a better life for its people.

The first thing that stood out for me in Pacem in Terris is that Pope John XXIII laid out the rights but also duties, beginning with the right to life:

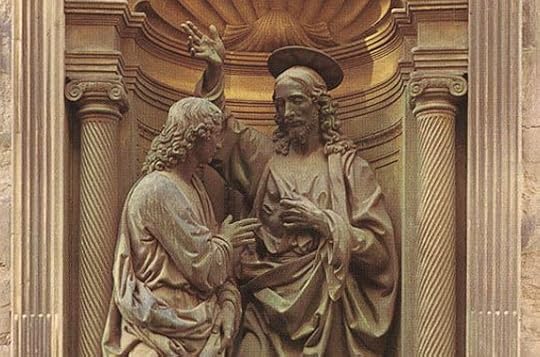

Jesus Christ, the Personification of Mercy

Detail of "The Doubting Thomas" (1476-83) by Andrea del Verrocchio

A Scriptural Reflection on the Readings for April 27, 2014, the Second Sunday of Easter/Divine Mercy Sunday | Carl E. Olson

Readings:

• Acts 2:42-47

• Psa 118:2-4, 13-15, 22-24

• 1 Pet 1:3-9

• Jn 20:19-31

As a young boy I enjoyed playing Little League baseball. On a couple of occasions, while playing a lesser opponent, our team would be so far ahead that the “mercy rule” took effect, meaning the game would end before all nine innings were played. This was meant to spare the other team embarrassment and to ensure the game ended in a timely manner.

Ordinary mercy involves having compassion and pity on another person. It usually assumes a certain relationship between those who have power and those who are powerless. It is based on the recognition, at some level, of the dignity of those who have less and who are vulnerable. Divine mercy goes even deeper and farther—so deep and far, in fact, that we cannot fully comprehend it. It flows from the heart of Jesus Christ, who not only has pity on us sinners but willingly allowed Himself to be disgraced, beaten, mocked, and killed for our sake.

In the language of sports, the crucified Christ was a “loser” so that we might, by His gift and grace, win eternal life. I say “loser” because we know, as today’s Gospel explains, that while Jesus lost His life by giving it up on the Cross, He was restored to life by the Father. Saint Gregory the Great wrote of the doubting Apostle Thomas, “It was not an accident that that particular disciple was not present,” referring to Christ’s first appearance to the frightened disciples in the locked room (Jn 20:19-24). “The divine mercy ordained that a doubting disciple should, by feeling in his Master the wounds of the flesh, heal in us the wounds of unbelief.”

It is tempting, I think, to sometimes look down on the Apostle Thomas, as though we would have readily accepted the witness of the other apostles. Perhaps. But the other disciples, at the first appearance of the risen Lord, also needed to see the hands and side of their Lord. In other words, Thomas asked for the same verification that Christ has given the others. As Saint Gregory indicates, Thomas’s doubt was used by God as a means of mercy for our sake, for the Christian faith is rooted in the historical event of the Resurrection and in the first-hand witness of those who saw, touched, and spoke with the risen Christ.

In April of 2000, Pope John Paul II officially established this second Sunday of Easter as the Sunday of Divine Mercy, recognizing the private revelations given by Jesus to Saint Faustina Kowalska. Saint Kowalska saw two rays of light shining from the heart of Christ, which, He explained to her, “represent blood and water.” Reflecting on this vision and Christ’s statement, John Paul II wrote, “Blood and water! We immediately think of the testimony given by the Evangelist John, who, when a solider on Calvary pierced Christ's side with his spear, sees blood and water flowing from it (cf. Jn 19: 34). Moreover, if the blood recalls the sacrifice of the Cross and the gift of the Eucharist, the water, in Johannine symbolism, represents not only Baptism but also the gift of the Holy Spirit (cf. Jn 3: 5; 4: 14; 7: 37-39).”

The divine mercy, then, involves the sacrificial self-gift that God offers to us, flowing from the heart of the Father, demonstrated in the death of the Son, and given by the power of the Holy Spirit. John Paul II, in his encyclical Dives in Misericordia—“On the Mercy of God” (Nov 30, 1980)—wrote that Christ “makes incarnate and personified [mercy]. He himself, in a certain sense, is mercy.”

In seeing Christ, man sees God and is able to enter into life-giving communion with Him. This beautiful truth is the focus of today’s epistle, written by Saint Peter, which speaks of the great mercy given by the Father through the resurrection of Jesus Christ. Life, of course, is not a game, nor is divine mercy a rule. It is a reality, a gift from the heart of Jesus Christ.

(This "Opening the Word" column originally appeared in the March 30, 2008, edition of Our Sunday Visitor newspaper.)

Carl E. Olson's Blog

- Carl E. Olson's profile

- 20 followers