Carl E. Olson's Blog, page 100

April 21, 2014

The Truth of the Resurrection

The Truth of the Resurrection | Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger | From Introduction to Christianity

To the Christian, faith in the Resurrection of Jesus Christ is an expression of certainty that the saying that seems to be only a beautiful dream is in fact true: "Love is strong as death" (Song 8:6). In the Old Testament this sentence comes in the middle of praises of the power of eros. But this by no means signifies that we can simply push it aside as a lyrical exaggeration. The boundless demands of eros", its apparent exaggerations and extravagance, do in reality give expression to a basic problem, indeed the" basic problem of human existence, insofar as they reflect the nature and intrinsic paradox of love: love demands infinity, indestructibility; indeed, it is, so to speak, a call for infinity. But it is  also a fact that this cry of love's cannot be satisfied, that it demands infinity but cannot grant it; that it claims eternity but in fact is included in the world of death, in its loneliness and its power of destruction. Only from this angle can one understand what "resurrection" means. It is" the greater strength of love in face of death.

also a fact that this cry of love's cannot be satisfied, that it demands infinity but cannot grant it; that it claims eternity but in fact is included in the world of death, in its loneliness and its power of destruction. Only from this angle can one understand what "resurrection" means. It is" the greater strength of love in face of death.

At the same time it is proof of what only immortality can create: being in the other who still stands when I have fallen apart. Man is a being who himself does not live forever but is necessarily delivered up to death. For him, since he has no continuance in himself, survival, from a purely human point of view, can only become possible through his continuing to exist in another. The statements of Scripture about the connection between sin and death are to he understood from this angle. For it now becomes clear that man's attempt "to be like God", his striving for autonomy, through which he wishes to stand on his own feet alone, means his death, for he just cannot stand on his own. If man--and this is the real nature of sin--nevertheless refuses to recognize his own limits and tries to be completely self-sufficient, then precisely by adopting this attitude he delivers himself up to death.

Of course man does understand that his life alone does not endure and that he must therefore strive to exist in others, so as to remain through them and in them in the land of the living. Two ways in particular have been tried. First, living on in one's own children: that is why in primitive peoples failure to marry and childlessness are regarded as the most terrible curse; they mean hopeless destruction, final death. Conversely, the largest possible number of children offers at the same time the greatest possible chance of survival, hope of immortality, and thus the most genuine blessing that man can expect. Another way discloses itself when man discovers that in his children he only continues to exist in a very unreal way; he wants more of himself to remain. So he takes refuge in the idea of fame, which should make him really immortal if be lives on through all ages in the memory of others. But this second attempt of man's to obtain immortality for himself by existing in others fails just as badly as the first: what remains is not the self but only its echo, a mere shadow. So self-made immortality is really only a Hades, a sheol": more nonbeing than being. The inadequacy of both ways lies partly in the fact that the other person who holds my being after my death cannot carry this being itself but only its echo; and even more in the fact that even time other person to whom I have, so to speak, entrusted my continuance will not last--he, too, will perish.

This leads us to the next step. We have seen so far that man has no permanence in himself. And consequently can only continue to exist in another but that his existence in another is only shadowy and once again not final, because this other must perish, too. If this is so, then only one could truly give lasting stability: he who is, who does not come into existence and pass away again but abides in the midst of transience: the God of the living, who does not hold just the shadow and echo of my being, whose ideas are not just copies of reality. I myself am his thought, which establishes me more securely, so to speak, than I am in myself; his thought is not the posthumous shadow but the original source and strength of my being. In him I can stand as more than a shadow; in him I am truly closer to myself than I should be if I just tried to stay by myself.

Before we return from here to the Resurrection, let us try to see the same thing once again from a somewhat different side. We can start again from the dictum about love and death and say: Only where someone values love more highly than life, that is, only where someone is ready to put life second to love, for the sake of love, can love be stronger and more than death. If it is to be more than death, it must first be more than mere life. But if it could be this, not just in intention but in reality, then that would mean at the same time that the power of love had risen superior to the power of the merely biological and taken it into its service. To use Teilhard de Chardin's terminology; where that took place, the decisive complexity or "complexification" would have occurred; bios, too, would be encompassed by and incorporated in the power of love. It would cross the boundary--death--and create unity where death divides. If the power of love for another were so strong somewhere that it could keep alive not just his memory, the shadow of his "I", but that person himself, then a new stage in life would have been reached. This would mean that the realm of biological evolutions and mutations had been left behind and the leap made to a quite different plane, on which love was no longer subject to bios but made use of it. Such a final stage of "mutation" and "evolution" would itself no longer be a biological stage; it would signify the end of the sovereignty of bios, which is at the same time the sovereignty of death; it would open up the realm that the Greek Bible calls zoe, that is, definitive life, which has left behind the rule of death. The last stage of evolution needed by the world to reach its goal would then no longer be achieved within the realm of biology but by the spirit, by freedom, by love. It would no longer be evolution but decision and gift in one.

But what has all this to do, it may be asked, with faith in the Resurrection of Jesus? Well, we previously considered the question of the possible immortality of man from two sides, which now turn out to be aspects of one and. the same state of affairs. We said that, as man has no permanence in himself, his survival could. only be brought about by his living on in another. And we said, from the point of view of this "other", that only the love that takes up the beloved in itself, into its own being, could make possible this existence in the other. These two complementary aspects are mirrored again, so it seems to me, in the two New Testament ways of describing the Resurrection of the Lord: "Jesus has risen" and "God (the Father) has awakened Jesus." The two formulas meet in the fact that Jesus' total love for men, which leads him to the Cross, is perfected in totally passing beyond to the Father and therein becomes stronger than death, because in this it is at the same time total "being held" by him.

From this a further step results. We can now say that love always establishes some kind of immortality; even in its prehuman stage, it points, in the form of preservation of the species, in this direction. Indeed, this founding of immortality is not something incidental to love, not one thing that it does among others, but what really gives it its specific character. This principle can be reversed; it then signifies that immortality always" proceeds from love, never out of the autarchy of that which is sufficient to itself. We may even be bold enough to assert that this principle, properly understood, also applies even to God as he is seen by the Christian faith. God, too, is absolute permanence, as opposed to everything transitory, for the reason that he is the relation of three Persons to one another, their incorporation in the "for one another" of love, act-substance of the love that is absolute and therefore completely "relative", living only "in relation to". As we said earlier, it is not autarchy, which knows no one but itself, that is divine; what is revolutionary about the Christian view of the world and of God, we found, as opposed to those of antiquity, is that it learns to understand the "absolute" as absolute "relatedness", as relatio subsistens.

To return to our argument, love is the foundation of immortality, and immortality proceeds from love alone. This statement to which we have now worked our way also means that he who has love for all has established immortality for all. That is precisely the meaning of the biblical statement that his Resurrection is our life. The--to us--curious reasoning of St. Paul in his First Letter to the Corinthians now becomes comprehensible: if he has risen, then we have, too, for then love is stronger than death; if he has not risen, then we have not either, for then the situation is still that death has the last word, nothing else (cf. I Cor 15:16f.). Since this is a statement of central importance, let us spell it out once again in a different way: Either love is stronger than death, or it is not. If it has become so in him, then it became so precisely as love for others. This also means, it is true, that our own love, left to itself, is not sufficient to overcome death; taken in itself it would have to remain an unanswered cry. It means that only his love, coinciding with God's own power of life and love, can be the foundation of our immortality. Nevertheless, it still remains true that the mode of our immortality will depend on our mode of loving. We shall have to return to this in the section on the Last Judgment.

A further point emerges from this discussion. Given the foregoing considerations, it goes without saying that the life of him who has risen from the dead is not once again bios, the biological form of our mortal life within history; it is zoe, new, different, definitive life; life that has stepped beyond the mortal realm of bios and history, a realm that has here been surpassed by a greater power. And in fact the Resurrection narratives of the New Testament allow us to see clearly that the life of the Risen One lies, not within the historical bios, but beyond and above it. It is also true, of course, that this new life begot itself in history and had to do so, because after all it is there for history, and the Christian message is basically nothing else than the transmission of the testimony that love has managed to break through death here and thus has transformed fundamentally the situation of all of us. Once we have realized this, it is no longer difficult to find the right kind of hermeneutics for the difficult business of expounding the biblical Resurrection narratives, that is, to acquire a clear understanding of the sense in which they must properly be understood. Obviously we cannot attempt here a detailed discussion of the questions involved, which today present themselves in a more difficult form than ever before; especially as historical and--for the most part inadequately pondered--philosophical statements are becoming more and more inextricably intertwined, and exegesis itself quite often produces its own philosophy, which is intended to appear to the layman as a supremely refined distillation of the biblical evidence. Many points of detail will here always remain open to discussion, but it is possible to recognize a fundamental dividing line between explanation that remains explanation and arbitrary adaptations [to contemporary ways of thinking].

First of all, it is quite clear that after his Resurrection Christ did not go back to his previous earthly life, as we are told the young man of Nain and Lazarus did. He rose again to definitive life, which is no longer governed by chemical and biological laws and therefore stands outside the possibility of death, in the eternity conferred by love. That is why the encounters with him are "appearances"; that is why he with whom people had sat at table two days earlier is not recognized by his best friends and, even when recognized, remains foreign: only where he grants vision is he seen; only when he opens men's eyes and makes their hearts open up can the countenance of the eternal love that conquers death become recognizable in our mortal world, and, in that love, the new, different world, the world of him who is to come. That is also why it is so difficult, indeed absolutely impossible, for the Gospels to describe the encounter with the risen Christ; that is why they can only stammer when they speak of these meetings and seem to provide contradictory descriptions of them. In reality they are surprisingly unanimous in the dialectic of their statements, in the simultaneity of touching and not touching, or recognizing and not recognizing, of complete identity between the crucified and the risen Christ and complete transformation. People recognize the Lord and yet do not recognize him again; people touch him, and yet he is untouchable; he is the same and yet quite different. As we have said, the dialectic is always the same; it is only the stylistic means by which it is expressed that changes.

For example, let us examine a little more closely from this point of view the Emmaus story, which we have already touched upon briefly. At first sight it looks as if we are confronted here with a completely earthly and material notion of resurrection; as if nothing remains of the mysterious and indescribable elements to be found in the Pauline accounts. It looks as if the tendency to detailed depiction, to the concreteness of legend, supported by the apologist's desire for something tangible, had completely won the upper hand and fetched the risen Lord right back into earthly history. But this impression is soon contradicted by his mysterious appearance and his no less mysterious disappearance. The notion is contradicted even more by the fact that here, too, he remains unrecognizable to the accustomed eye. He cannot be firmly grasped as he could be in the time of his earthly life; he is discovered only in the realm of faith; he sets the hearts of the two travelers aflame by his interpretation of the Scriptures and by breaking bread he opens their eyes. This is a reference to the two basic elements in early Christian worship, which consisted of the liturgy of the word (the reading and expounding of Scripture) and the eucharistic breaking of bread. In this way the evangelist makes it clear that the encounter with the risen Christ lies on a quite new plane; he tries to describe the indescribable in terms of the liturgical facts. He thereby provides both a theology of the Resurrection and a theology of the liturgy: one encounters the risen Christ in the word and in the sacrament; worship is the way in which he becomes touchable to us and, recognizable as the living Christ. And conversely, the liturgy is based on the mystery of Easter; it is to he understood as the Lords approach to us. In it he becomes our traveling companion, sets our dull hearts aflame, and opens our sealed eyes. He still walks with us, still finds us worried and downhearted, and still has the power to make us see.

Of course, all this is only half the story; to stop at this alone would mean falsifying the evidence of the New Testament. Experience of the risen Christ is something other than a meeting with a man from within our history, and it must certainly not be traced back to conversations at table and recollections that would have finally crystallized in the idea that he still lived and went about his business. Such an interpretation reduces what happened to the purely human level and robs it of its specific quality. The Resurrection narratives are something other and more than disguised liturgical scenes: they make visible the founding event on which all Christian liturgy rests. They testify to an approach that did not rise from the hearts of the disciples but came to them from outside, convinced them despite their doubts and made them certain that the Lord had truly risen. He who lay in the grave is no longer there; he--really he himself--lives. He who had been transposed into the other world of God showed himself powerful enough to make it palpably clear that he himself stood in their presence again, that in him the power of love had really proved itself stronger than the power of death.

Only by taking this just as seriously as what we said first does one remain faithful to the witness borne by the New Testament; only thus, too, is its seriousness in world history preserved. The comfortable attempt to spare oneself the belief in the mystery of God's mighty actions in this world and yet at the same time to have the satisfaction of remaining on the foundation of the biblical message leads nowhere; it measures up neither to the honesty of reason nor to the claims of faith. One cannot have both the Christian faith and "religion within the bounds of pure reason"; a choice is unavoidable. He who believes will see more and more clearly, it is true, how rational it is to have faith in the love that has conquered death.

Related IgnatiusInsight.com Articles:

• Seeing Jesus in the Gospel of John | Excerpts from On The Way to Jesus Christ | Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger

• A Jesus Worth Dying For | A Review of On The Way to Jesus Christ | Justin Nickelsen

• Encountering Christ in the Gospel | Excerpt from My Jesus | Christoph Cardinal Schönborn

• The Divinity of Christ | Peter Kreeft

• Jesus Is Catholic | Hans Urs von Balthasar

• The Religion of Jesus | Blessed Columba Marmion | From Christ, The Ideal of the Priest

• Author Page for Joseph Ratzinger/Pope Benedict XVI

Joseph Ratzinger, now Pope Benedict XVI, was for over two decades the Prefect for the Congregation of the Doctrine of the Faith under Pope John Paul II. He is a renowned theologian and author of numerous books. A mini-bio and full listing of his books published by Ignatius Press are available on his IgnatiusInsight.com Author Page.

April 20, 2014

Resurrection and Witness

Detail from "Noli Me Tangere" (1440-42) by Fra Angelico (Wikipaintings.com)

Resurrection and Witness | Carl E. Olson | CWR

The Readings for the Solemnity of Easter show how the faith of the first Christians was squarely based on historical events and objective truth

Imagine for a moment that the Apostle Peter, standing before the Roman centurion Cornelius, had said, with a somewhat embarrassed grimace, “Well, it’s my personal opinion that Jesus rose from the dead—whatever that means. But that’s simply my truth, and is just one possible explanation.”

It sounds ridiculous. It is ridiculous. But it’s impossible to ignore that such words have often come from the lips of many modern-day Christians. Perhaps they have only a passing knowledge of what Scripture, Tradition, and history say about the Resurrection. Perhaps they don’t wish to offend those who scoff at such a “simplistic” acceptance of a supernatural event.

Or perhaps they feel that different people really can have different “truths”, none better than another.

But Peter’s words were direct and bold. “We are witnesses of all that he did…” he said, “This man God raised on the third day and granted that he be visible, not to all the people, but to us, the witnesses chosen by God in advance…” (Acts 10:39, 40). Such words are, to many people today, triumphalistic and exclusive and arrogant. But, then, we live in an age in which the only firm belief given a free pass is the belief that faith is not believable. “Faith” is seen as superstitious, based—at best—on feelings and intuitions, not related to anything verifiable and concrete.

Yet St. Cyril of Jerusalem, writing some 1700 years ago, noted that when Peter and John first ran to the empty tomb they did not, at that very moment, “meet Christ risen from the dead, but they infer his resurrection from the bundle of linen clothes” and connected that physical fact to Jesus’ own words and the prophecies of Scripture. “When, therefore, they looked at the issues of events in the light of the prophecies that turned out true, their faith was from that time forward rooted on a firm foundation.”

What the two men saw was unexpected and astounding, but they didn’t give themselves over to irrational judgments or emotional conjectures, but began to logically put together the pieces of the prophetic puzzle.

Fr. Hans Urs von Balthasar, in commenting on this same event, observed that Peter represents the ecclesial office—the Papacy—and John, the mystical theologian beloved by Christ, symbolizes ecclesial love. They run together to the tomb, but Love, not burdened by the cares of the Office, runs faster. “Yet Love yields to Office when it comes to examining the tomb, and Peter thus becomes the first to view the cloth that had covered Jesus’ head and establish that no theft had occurred.” Then Love—that is, John—entered, “and he saw and believed.” This indicated, von Balthasar stated, that “faith in Jesus is justified despite all the opaqueness of the situation.”

By the time Peter preached on Pentecost (Acts 2:14-36) and, later, to the household of Cornelius, the opaqueness had completely dissolved in the light of the risen Christ. Peter and the apostles were witnesses—and it is important to note that the Greek root word for “witness” and “testimony” (Jn. 21:24) is martus, from which comes “martyr”. Peter, in particular, had a special role as witness. “If being a Christian essentially means believing in the risen Lord”, wrote Pope Benedict XVI in Jesus of Nazareth: Holy Week, “then Peter’s special witnessing role is a confirmation of his commission to be the rock on which the Church is built.”

This is brought home emphatically in the final chapter of John’s Gospel, where Peter’s place as head apostle was reaffirmed by Jesus—“Feed my lambs … Tend my sheep … Feed my sheep”—and then further affirmed by the promise of martyrdom (Jn. 21:15-19).

When it comes to Jesus and the Resurrection, the world offers a host of opinions, most of which dismiss and deny the possibility that “this man” was “raised on the third day” by God. But, as Blessed John Cardinal Newman pointed out, “No one is a martyr for a conclusion, no one is a martyr for an opinion; it is faith that makes martyrs.”

(This essay originally appeared in the April 24, 2011, edition of Our Sunday Visitor newspaper in a slightly different form.)

April 18, 2014

The Question of Suffering, the Response of the Cross

The Question of Suffering, the Response of the Cross | Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger

An excerpt from God and the World: A Conversation with Peter Seewald (Ignatius Press, 2002), by Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, pages 332-36, 333.

Seewald: We are used to thinking of suffering as something we try to avoid at all costs. And there is nothing that many societies get more angry about than the Christian idea that one should bear with pain, should endure suffering, should even sometimes give oneself up to it, in order thereby to overcome it. "Suffering", John Paul II believes, "is a part of the mystery of being human." Why is this?

Cardinal Ratzinger: Today what people have in view is eliminating suffering from the world. For the individual, that means avoiding pain and suffering in whatever way. Yet we must also see that it is in this very way that the world becomes very hard and very cold. Pain is part of being human. Anyone who really wanted to get rid of suffering would have to get rid of love before anything else, because there can be no love without suffering, because it always demands an element of self-sacrifice, because, given temperamental differences and the drama of situations, it will always bring with it renunciation and pain.

Cardinal Ratzinger: Today what people have in view is eliminating suffering from the world. For the individual, that means avoiding pain and suffering in whatever way. Yet we must also see that it is in this very way that the world becomes very hard and very cold. Pain is part of being human. Anyone who really wanted to get rid of suffering would have to get rid of love before anything else, because there can be no love without suffering, because it always demands an element of self-sacrifice, because, given temperamental differences and the drama of situations, it will always bring with it renunciation and pain.

When we know that the way of love–this exodus, this going out of oneself–is the true way by which man becomes human, then we also understand that suffering is the process through which we mature. Anyone who has inwardly accepted suffering becomes more mature and more understanding of others, becomes more human. Anyone who has consistently avoided suffering does not understand other people; he becomes hard and selfish.

Love itself is a passion, something we endure. In love experience first a happiness, a general feeling of happiness.

Yet on the other hand, I am taken out of my comfortable tranquility and have to let myself be reshaped. If we say that suffering is the inner side of love, we then also understand it is so important to learn how to suffer–and why, conversely, the avoidance of suffering renders someone unfit to cope with life. He would be left with an existential emptiness, which could then only be combined with bitterness, with rejection and no longer with any inner acceptance or progress toward maturity.

Seewald: What would actually have happened if Christ had not appeared and if he had not died on the tree of the Cross? Would the world long since have come to ruin without him?

Cardinal Ratzinger: That we cannot say. Yet we can say that man would have no access to God. He would then only be able to relate to God in occasional fragmentary attempts. And, in the end, he would not know who or what God actually is.

Something of the light of God shines through in the great religions of the world, of course, and yet they remain a matter of fragments and questions. But if the question about God finds no answer, if the road to him is blocked, if there is no forgiveness, which can only come with the authority of God himself, then human life is nothing but a meaningless experiment. Thus, God himself has parted the clouds at a certain point. He has turned on the light and has shown us the way that is the truth, that makes it possible for us to live and that is life itself.

Seewald: Someone like Jesus inevitably attracts an enormous amount of attention and would be bound to offend any society. At the time of his appearance, the prophet from Nazareth was not only cheered, but also mocked and persecuted. The representatives of the established order saw in Jesus' teaching and his person a serious threat to their power, and Pharisees and high priests began to seek to take his life. At the same time, the Passion was obviously part and parcel of his message, since Christ himself began to prepare his disciples for his suffering and death. In two days, he declared at the beginning of the feast of Passover, "the Son of Man will be betrayed and crucified."

Cardinal Ratzinger: Jesus is adjusting the ideas of the disciples to the fact that the Messiah is not appearing as the Savior or the glorious powerful hero to restore the renown of Israel as a powerful state, as of old. He doesn't even call himself Messiah, but Son of Man. His way, quite to the contrary, lies in powerlessness and in suffering death, betrayed to the heathen, as he says, and brought by the heathen to the Cross. The disciples would have to learn that the kingdom of God comes into the world in that way, and in no other.

Seewald: A world-famous picture by Leonardo da Vinci, the Last Supper, shows Jesus' farewell meal in the circle of his twelve apostles. On that evening, Jesus first of all throws them all into terror and confusion by indicating that he will be the victim of betrayal. After that he founds the holy Eucharist, which from that point onward has been performed by Christians day after day for two thousand years.

"During the meal," we read in the Gospel, "Jesus took the bread and spoke the blessing; then he broke the bread, shared it with the disciples, and said: Take and eat; this is my body. Then he took the cup, spoke the thanksgiving, and passed it to the disciples with the words: Drink of this, all of you; this is my blood, the blood of the New Covenant, which is shed for you and for many for the forgiveness of sins. Do this in remembrance of me." These are presumably the sentences that have been most often pronounced in the entire history of the world up till now. They give the impression of a sacred formula.

Cardinal Ratzinger: They are a sacred formula. In any case, these are words that entirely fail to fit into any category of what would be usual, what could be expected or premeditated. They are enormously rich in meaning and enormously profound. If you want to get to know Christ, you can get to know him best by meditating on these words, and by getting to know the context of these words, which have become a sacrament, by joining in the celebration. The institution of the Eucharist represents the sum total of what Christ Is.

Here Jesus takes up the essential threads of the Old Testament. Thereby he relies on the institution of the Old Covenant, on Sinai, on one hand, thus making clear that what was begun on Sinai is now enacted anew: The Covenant that God made with men is now truly perfected. The Last Supper is the rite of institution of the New Covenant. In giving himself over to men, he creates a community of blood between God and man.

On the other hand, some words of the prophet Jeremiah are taken up here, proclaiming the New Covenant. Both strands of the Old Testament (Law and prophets) are amalgamated to create this unity and, at the same time, shaped into a sacramental action. The Cross is already anticipated in this. For when Christ gives his Body and his Blood, gives himself, then this assumes that he is really giving up his life. In that sense, these words are the inner act of the Cross, which occurs when God transforms this external violence against him into an act of self-donation to mankind.

And something else is anticipated here, the Resurrection. You cannot give anyone dead flesh, dead body to eat. Only because he is going to rise again are his Body and his Blood new. It is no longer cannibalism but union with the living, risen Christ that is happening here.

In these few words, as we see, lies a synthesis of the history of religion—of the history of Israel's faith, as well as of Jesus' own being and work, which finally becomes a sacrament and an abiding presence. ...

Seewald: The soldiers abuse Jesus in a way we can hardly imagine. All hatred, everything bestial in man, utterly abysmal, the most horrible things men can do to one another, is obviously unloaded onto this man.

Cardinal Ratzinger: Jesus stands for all victims of brute force. In the twentieth century itself we have seen again how inventive human cruelty can be; how cruelty, in the act of destroying the image of man in others, dishonors and destroys that image in itself. The fact that the Son of God took all this upon himself in exemplary manner, as the "Lamb of God", is bound to make us shudder at the cruelty of man, on one hand, and make us think carefully about ourselves, how far we are willing to stand by as cowardly or silent onlookers, or how far we share responsibility ourselves. On the other side, it is bound to transform us and to make us rejoice in God. He has put himself on the side of the innocent and the suffering and would like to see us standing there too.

Related IgnatiusInsight.com Articles and Book Excerpts:

• Author Page for Joseph Ratzinger/Pope Benedict XVI

• The Truth of the Resurrection | Excerpts from Introduction to Christianity | Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger

• Seeing Jesus in the Gospel of John | Excerpts from On The Way to Jesus Christ | Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger

• God Made Visible | A Review of On The Way to Jesus Christ | Justin Nickelsen

• A Shepherd Like No Other | Excerpt from Behold, God's Son! | Christoph Cardinal Schönborn

• Encountering Christ in the Gospel | Excerpt from My Jesus | Christoph Cardinal Schönborn

• A Jesus Worth Dying For | On the Foreword to Benedict XVI's Jesus of Nazareth | Fr. James V. Schall, S.J.

• The Divinity of Christ | Peter Kreeft

• Jesus Is Catholic | Hans Urs von Balthasar

• The Religion of Jesus | Blessed Columba Marmion | From Christ, The Ideal of the Priest

• Studying The Early Christians | The Introduction to We Look For the Kingdom: The Everyday Lives of the Early Christians | Carl J. Sommer

• The Everyday Lives of the Early Christians | An interview with Carl J. Sommer

"The Cross–For Us" by Hans Urs von Balthasar

The Cross–For Us | Hans Urs von Balthasar | An excerpt from A Short Primer For Unsettled Laymen

Without a doubt, at the center of the New Testament there stands the Cross, which receives its interpretation from the Resurrection.

The Passion narratives are the first pieces of the Gospels that were composed as a unity. In his preaching at Corinth, Paul initially wants to know  nothing but the Cross, which "destroys the wisdom of the wise and wrecks the understanding of those who understand", which "is a scandal to the Jews and foolishness to the gentiles". But "the foolishness of God is wiser than men, and the weakness of God is stronger than men" (I Cor 1:19, 23, 25).

nothing but the Cross, which "destroys the wisdom of the wise and wrecks the understanding of those who understand", which "is a scandal to the Jews and foolishness to the gentiles". But "the foolishness of God is wiser than men, and the weakness of God is stronger than men" (I Cor 1:19, 23, 25).

Whoever removes the Cross and its interpretation by the New Testament from the center, in order to replace it, for example, with the social commitment of Jesus to the oppressed as a new center, no longer stands in continuity with the apostolic faith. He does not see that God's commitment to the world is most absolute precisely at this point across a chasm.

It is certainly not surprising that the disciples were able to understand the meaning of the Cross only slowly, even after the Resurrection. The Lord himself gives a first catechetical instruction to the disciples at Emmaus by showing that this incomprehensible event is the fulfillment of what had been foretold and that the open question marks of the Old Testament find their solution only here (Lk 24:27).

Which riddles? Those of the Covenant between God and men in which the latter must necessarily fail again and again: who can be a match for God as a partner? Those of the many cultic sacrifices that in the end are still external to man while he himself cannot offer himself as a sacrifice. Those of the inscrutable meaning of suffering which can fall even, and especially, on the innocent, so that every proof that God rewards the good becomes void. Only at the outer periphery, as something that so far is completely sealed, appear the outlines of a figure in which the riddles might be solved.

This figure would be at once the completely kept and fulfilled Covenant, even far beyond Israel (Is 49:5-6), and the personified sacrifice in which at the same time the riddle of suffering, of being despised and rejected, becomes a light; for it happens as the vicarious suffering of the just for "the many" (Is 52:13-53:12). Nobody had understood the prophecy then, but in the light of the Cross and Resurrection of Jesus it became the most important key to the meaning of the apparently meaningless.

Did not Jesus himself use this key at the Last Supper in anticipation? "For you", "for the many", his Body is given up and his Blood is poured out. He himself, without a doubt, foreknew that his will to help these" people toward God who are so distant from God would at some point be taken terribly seriously, that he would suffer in their place through this distance from God, indeed this utmost darkness of God, in order to take it from them and to give them an inner share in his closeness to God. "I have a baptism to be baptized with, and how I am constrained until it is accomplished!" (Lk 12:50).

It stands as a dark cloud at the horizon of his active life; everything he does then-healing the sick, proclaiming the kingdom of God, driving out evil spirits by his good Spirit, forgiving sins-all of these partial engagements happen in the approach toward the one unconditional engagement.

As soon as the formula "for the many", "for you", "for us", is found, it resounds through all the writings of the New Testament; it is even present before anything is written down (cf. i Cor 15:3). Paul, Peter, John: everywhere the same light comes from the two little words.

What has happened? Light has for the first time penetrated into the closed dungeons of human and cosmic suffering and dying. Pain and death receive meaning.

Not only that, they can receive more meaning and bear more fruit than the greatest and most successful activity, a meaning not only for the one who suffers but precisely also for others, for the world as a whole. No religion had even approached this thought. [1] The great religions had mostly been ingenious methods of escaping suffering or of making it ineffective. The highest that was reached was voluntary death for the sake of justice: Socrates and his spiritualized heroism. The detached farewell discourses of the wise man in prison could be compared from afar to the wondrous farewell discourses of Christ.

But Socrates dies noble and transfigured; Christ must go out into the hellish darkness of godforsakenness, where he calls for the lost Father "with prayers and supplications, with loud cries and tears" (Heb 5:7). Why are such stories handed down? Why has the image of the hero, the martyr, thus been destroyed? It was "for us", "in our place".

One can ask endlessly how it is possible to take someone's place in this way. The only thing that helps us who are perplexed is the certainty of the original Church that this man belongs to God, that "he truly was God's Son", as the centurion acknowledges under the Cross, so that finally one has to render him homage in adoration as "my Lord and my God" Jn 20:28).

Every theology that begins to blink and stutter at this point and does not want to come out with the words of the Apostle Thomas or tinkers with them will not hold to the "for us". There is no intermediary between a man who is God and an ordinary mortal, and nobody will seriously hold the opinion that a man like us, be he ever so courageous and generous in giving himself, would be able to take upon himself the sin of another, let alone the sin of all. He can suffer death in the place of someone who is condemned to death. This would be generous, and it would spare the other person death at least for a time.

But what Christ did on the Cross was in no way intended to spare us death but rather to revalue death completely. In place of the "going down into the pit" of the Old Testament, it became "being in paradise tomorrow". Instead of fearing death as the final evil and begging God for a few more years of life, as the weeping king Hezekiah does, Paul would like most of all to die immediately in order "to be with the Lord" (Phil 1:23). Together with death, life is also revalued: "If we live, we live to the Lord; if we die, we die to the Lord" (Rom 14:8).

But the issue is not only life and death but our existence before God and our being judged by him. All of us were sinners before him and worthy of condemnation. But God "made the One who knew no sin to be sin, so that we might be justified through him in God's eyes" (2 Cor 5:21).

Only God in his absolute freedom can take hold of our finite freedom from within in such a way as to give it a direction toward him, an exit to him, when it was closed in on itself. This happened in virtue of the "wonderful exchange" between Christ and us: he experiences instead of us what distance from God is, so that we may become beloved and loving children of God instead of being his "enemies" (Rom 5:10).

Certainly God has the initiative in this reconciliation: he is the one who reconciles the world to himself in Christ. But one must not play this down (as famous theologians do) by saying that God is always the reconciled God anyway and merely manifests this state in a final way through the death of Christ. It is not clear how this could be the fitting and humanly intelligible form of such a manifestation.

No, the "wonderful exchange" on the Cross is the way by which God brings about reconciliation. It can only be a mutual reconciliation because God has long since been in a covenant with us. The mere forgiveness of God would not affect us in our alienation from God. Man must be represented in the making of the new treaty of peace, the "new and eternal covenant". He is represented because we have been taken over by the man Jesus Christ. When he "signs" this treaty in advance in the name of all of us, it suffices if we add our name under his now or, at the latest, when we die.

Of course, it would be meaningless to speak of the Cross without considering the other side, the Resurrection of the Crucified. "If Christ has not risen, then our preaching is nothing and also your faith is nothing; you are still in your sins and also those who have fallen asleep . . . are lost. If we are merely people who have put their whole hope in Christ in this life, then we are the most pitiful of all men" (I Cor 15:14, 17-19).

If one does away with the fact of the Resurrection, one also does away with the Cross, for both stand and fall together, and one would then have to find a new center for the whole message of the gospel. What would come to occupy this center is at best a mild father-god who is not affected by the terrible injustice in the world, or man in his morality and hope who must take care of his own redemption: "atheism in Christianity".

Endnotes:

[1] For what is meant here is something qualitatively completely different from the voluntary or involuntary scapegoats who offered themselves or were offered (e.g., in Hellas or Rome) for the city or for the fatherland to avert some catastrophe that threatened everyone.

Related IgnatiusInsight.com Articles:

• Jesus Is Catholic | Hans Urs von Balthasar

• Seeing Jesus in the Gospel of John | Excerpts from On The Way to Jesus Christ | Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger

• A Jesus Worth Dying For | Justin Nickelsen

• Encountering Christ in the Gospel | Excerpt from My Jesus | Christoph Cardinal Schönborn

• The Divinity of Christ | Peter Kreeft

• The Religion of Jesus | Blessed Columba Marmion | From Christ, The Ideal of the Priest

• Christ, the Priest, and Death to Sin | Blessed Columba Marmion | From Christ, The Ideal of the Priest

Hans Urs von Balthasar (1905-88) was a Swiss theologian, considered to one of the most important Catholic intellectuals and writers of the twentieth century. 2005 marks the centennial celebration of his birth.

Hans Urs von Balthasar (1905-88) was a Swiss theologian, considered to one of the most important Catholic intellectuals and writers of the twentieth century. 2005 marks the centennial celebration of his birth.

Incredibly prolific and diverse, he wrote over one hundred books and hundreds of articles. Read more about his life and work in the Author's Pages section of IgnatiusInsight.com.

John Paul II and The Blessed Sacrament

The following is Chapter 9, "The Blessed Sacrament", from Jason Evert's new book, Saint John Paul the Great: His Five Loves.

Between 5:00 and 5:30 a.m.—and sometimes as early as 4:00—Pope John Paul II would arise each morning, keeping virtually the same schedule he had as the bishop of Kraków. Although he enjoyed watching the sunrise, the main reason for his early start was to make time for prayer. He prayed the Rosary prostrate on the floor or kneeling, followed by his personal prayers, and would then go to the chapel in order to prepare for 7:30 Mass. According to his press secretary, Joaquín Navarro-Valls, his sixty to ninety minutes of private prayer before Mass were the best part of his day.

At the chapel, he would kneel before the Blessed Sacrament at his prie-dieu. The top of his wooden kneeler could be opened, and it was brimming with notes people had given to him, seeking his prayers for all kinds of petitions, including healings, the conversion of family members, or successful pregnancies. Perhaps thirty to forty new petitions were given to him each day, and he would pray specifically over every one. He said that they were kept there and were always present "in my consciousness, even if they cannot be literally repeated every day."

He told one of his biographers, "There was a time when I thought that one had to limit the ‘prayer of petition.’ That time has passed. The further I advance along the road mapped out for me by Providence, the more I feel the need to have recourse to this kind of prayer." Quite often, those who sent the petitions wrote back in thanksgiving for answered prayers. His assistant secretary noted that most of them expressed gratitude for the gift of parenthood. Not only did he intercede before the tabernacle for these individuals as if they were his most intimate friends, he routinely sought information about the progress of the cases. The liturgy would not begin until he had before him the petitions people had asked him to offer on their behalf.

After going to the sacristy to don his vestments for Mass, he would again kneel or sit for ten to twenty minutes.When visitors arrived to join him for Mass, they would always find him kneeling in prayer. Some said, "he looked like he was speaking with the Invisible." One of the masters of ceremonies added, "it seemed as if the Pope were not present among us." Bishop Andrew Wypych, who was ordained to the diaconate by Cardinal Karol Wojtyła, added, "You could see that he physically was there, but one could sense that he was immersed in the love of the Lord. They were united in talking to each other."

During the celebration of the Eucharist, one observer noticed, "He lingered lovingly over every syllable that recalled the Last Supper as if the words were new to him."

April 17, 2014

Holy Thursday, Footwashing, and the Institution of the Priesthood

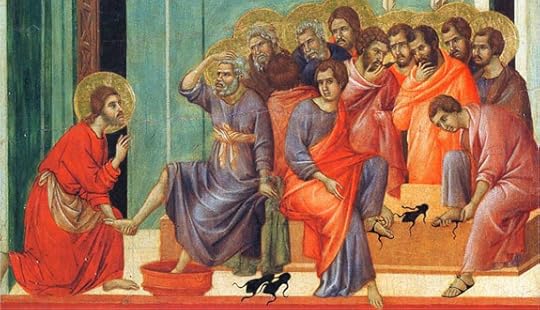

Detail from "Washing of feet" (1308-11) by Duccio di Buoninsegna

Holy Thursday, Footwashing, and the Institution of the Priesthood | Leroy Huizenga | CWR

Interpreting Scripture for its moral import alone, while common and understandable, can cause us to miss the deeper meaning of Christ's actions

In many Catholic parishes on Holy Thursday, a footwashing ritual is incorporated into Mass. Although optional, most parishes choose to do it, for it is a most powerful symbol in the present day, just as it is a powerful symbol at its Scriptural roots in the thirteenth chapter of the Gospel of John, when Jesus himself washes his disciples’ feet.

But a symbol of what? The most obvious answer is that the footwashing ritual is a symbol of humble service, given the extreme indignity involved in washing feet in the ancient world, a task usually reserved for the lowest slave of the house. Indeed, Jesus’ own explicit words seem to present it as such: “If I then, your Lord and Teacher, have washed your feet, you also ought to wash one another’s feet. For I have given you an example, that you also should do as I have done to you” (Jn. 13:14-15).

However, some see the footwashing ritual not as a symbol of service but a symbol of exclusion serving to reinforce patriarchy, for when done according to the Church’s rubrics, only the feet of males are to be washed. The question, then, concerns why the rubrics for the ritual command that viri selecti—“chosen males”—have their feet washed, and not women.

Basis for Holy Orders

The answer is that the footwashing scene in the Gospel of John is not only meant to be an example of humble service, but primarily a record of the institution of the Christian priesthood and thus the Scriptural root of the sacrament of holy orders.

Interpreting Scripture for its moral import is the default approach for most novice readers and many professional interpreters of Scripture, as it’s the easiest way to read the Bible and seems to make the Bible relevant.

The Easter Triduum: Entering into the Paschal Mystery

The Easter Triduum: Entering into the Paschal Mystery | Carl E. Olson

The liturgical year is a great and ongoing proclamation by the Church of the Gospel of Jesus Christ and a celebration of the Mystery of the Word. Through this yearly cycle, the Catechism of the Catholic Church explains, "the various aspects of the one Paschal mystery unfold"(CCC 1171). The Easter Triduum holds a special place in the liturgical year because it marks the culmination of the yearly celebration in proclaiming the Passion and Resurrection of Jesus Christ.

The Latin word triduum refers to a period of three days and has long been used to describe various three-day observances that prepared for a feast day through liturgy, prayer, and fasting. But it is most often used to describe the three days prior to the great feast of Easter: Holy Thursday, Good Friday, and Holy Saturday and the Easter Vigil. The General Norms for the Liturgical Year state that the Easter Triduum begins with the evening Mass of the Lord's Supper on Holy Thursday, "reaches its high point in the Easter Vigil, and closes with evening prayer on Easter Sunday" (par 19).

Just as Sunday is the high point of the week, Easter is the high point of the year. The meaning of the great feast is revealed and anticipated throughout the Triduum, which brings the people of God into contact – through liturgy, symbol, and sacrament – with the central events of the life of Christ: the Last Supper, His trial and crucifixion, His time in the tomb, and His Resurrection from the dead. In this way, "the mystery of the Resurrection, in which Christ crushed death, permeates with its powerful energy our old time, until all is subjected to him" (CCC 1169). During these three days of contemplation and anticipation the liturgies emphasize the sacrificial death of Christ on the Cross, and the sacraments of baptism and the Eucharist, by which the faithful enter into the life-giving Passion of Christ and grow in hope of eternal life in Him.

Holy Thursday | The Lord's Supper

The Triduum begins with the evening Mass of the Lord’s Supper on Holy Thursday, which commemorates when the Eucharist was instituted at the Last Supper by Jesus. The traditional English name for this day, "Maundy Thursday", comes from the Latin phrase Mandatum novum – "a new command" (or mandate) – which comes from Christ’s words: "A new commandment I give to you, that you love one another; even as I have loved you, that you also love one another" (Jn 13:34). The Gospel reading for the liturgy is from the first part of the same chapter and depicts Jesus washing the feet of the disciples, an act of servitude (commonly done by slaves or servants in ancient cultures) and great humility.

Earlier on Holy Thursday (or earlier in the week) the bishop celebrates the Chrism Mass, which focuses on the ordained priesthood and the public renewal by priests of their promises to faithfully fulfill their office. In the evening liturgy, the priest, who is persona Christi, will wash the feet of several parishioners, oftentimes catechumens and candidates who will be entering into full communion with the Church at Easter Vigil. In this way the many connections between the Eucharist, salvation, self-sacrifice, and service to others are brought together.

These realities are further anticipated in Jesus’ remark about the approaching betrayal by Judas: "Whoever has bathed has no need except to have his feet washed, for he is clean all over; so you are clean, but not all." The sacrificial nature of the Eucharist is brought out in the Old Testament reading, from Exodus 12, which recounts the first Passover and God’s command for the people of Israel, enslaved in Egypt, to kill a perfect lamb, eat it, and then spread its blood over the door as a sign of fidelity to the one, true God. Likewise, the reading from Paul’s epistle to the Christians in Corinth (1 Cor 11) repeats the words given by the Son of God to His apostles at the Last Supper: "This is my body that is for you. Do this in remembrance of me" and "This cup is the new covenant in my blood. Do this, as often as you drink it, in remembrance of me."

Thus, in this memorial of Jesus’ last meal with His disciples, the faithful are reminded of the everlasting value of that meal, the gift of the priesthood, the grave dangers of turning away from God, the necessity of the approaching Cross, and the abiding love that the Lord has for His people.

Good Friday | Veneration of the Cross

This is the first full day of the Easter Triduum, a day commemorating the Passion, Cross, and death of Jesus Christ, and therefore a day of strict fasting. The liturgy is profoundly austere, perhaps the most simple and stark liturgy of the entire year. The liturgy of the Lord’s Passion consists of three parts: the liturgy of the Word, the veneration of the Cross, and the reception of Communion. Although Communion is given and received, this liturgy is not a Mass; this practice dates back to the earliest years of the Church and is meant to emphasize the somber, mournful character of the day. The Body of Christ that is received by the faithful on Good Friday was consecrated the prior evening at the Mass of the Lord’s Supper and, in most cases, was adored until midnight or another late hour.

The liturgy of the Word begins with silence. After a prayer, there are readings from Isaiah 52 and 53 (about the suffering Servant), Psalm 31 (a great Messianic psalm), and the epistle to the Hebrews (about Christ the new and eternal high priest). Each of these readings draws out the mystery of the suffering Messiah who conquers through death and who is revealed through what seemingly destroys Him. Then the Passion from the Gospel of John (18:1-19:42) is proclaimed, often by several different lectors reading respective parts (Jesus, the guards, Peter, Caiaphas the high priest, Pilate, the soldiers). In this reading the great drama of the Passion unfolds, with Jew and Gentile, male and female, and the powerful and the weak all revealed for who they are and how their choices to follow or deny Christ will affect their lives and the lives of others.

The simple, direct form of the Good Friday liturgy and readings brings the faithful face to face with the cross, the great scandal and paradox of Christianity. The cross is solemnly venerated after intercessory prayers are offered for the world and for all people. The deacon (or another minister) brings out the veiled cross in procession. The priest takes the cross, stands with it in front of the altar and faces the people, then uncovers the upper part of the cross, the right arm of the cross, and then the entire cross. As he unveils each part, he sings, "This is the wood of the cross." He places the cross and then venerates it; other clergy, lay ministers, and the faithful then approach and venerate the cross by touching or kissing it. In this way each person acknowledges the instrument of Christ’s death and publicly demonstrates their willingness to take up their cross and follow Christ, regardless of what trials and sufferings it might involve.

Afterward, the faithful receive Communion and then depart silently. In the Byzantine rite, Communion is not even offered on this day. At Vespers a "shroud" bearing a painting of the lifeless Christ is carried in a burial procession, and the faithful keep vigil before it through the night.

Holy Saturday and Easter Vigil | The Mother of All Vigils

The ancient Church celebrated Holy Saturday with strict fasting in preparation of the celebration of Easter. After sundown the Christians would hold an all-night vigil, which concluded with baptism and Eucharist at the break of dawn. The same idea (if not the identical timeline) is found in the Easter Vigil today, which is the high point of the Easter Triduum and is filled with an abundance of readings, symbols, ceremony, and sacraments.

The Easter Vigil, the Church states, ranks "the mother of all vigils" (General Norms, 21). Being a vigil – a time of anticipation and preparation – it takes place at night, starting after nightfall and finishing before daybreak on Easter, thus beginning and ending in darkness. It consists of four general parts: the Service of Light, the Liturgy of the Word, Christian Initiation, and Liturgy of the Eucharist.

The Service of Light begins outdoors (or in a space outside of the main sanctuary) and in darkness. A fire is lit and blessed, and then the Paschal candle, which symbolizes the light of Christ, is lit from the fire by the priest, who proclaims: "May the light of Christ, rising in glory, dispel the darkness of our hearts and minds." The biblical themes of light removing darkness and life overcoming death suffuse the entire Vigil. The Paschal candle will be placed in the sanctuary (usually by the altar) for the Easter season, then will be kept in the baptistery so that when the sacrament of baptism is administered the candles of the baptized can be lit from it.

The faithful then join in procession back to the main sanctuary. The deacon (or priest, if no deacon is present), carries the Paschal Candle, lifting it three different times and chanting: "Christ our Light!" The people respond by singing, "Thanks be to God!" Everyone’s candles are lit from the Paschal candle and the faithful return in procession into the sanctuary. Then the Exultet is sung by the deacon (or priest or cantor). This is an ancient and beautiful poetic hymn of praise to God for the light of the Paschal candle. It may be as old as Saint Ambrose (d. 397) and has been part of the Roman tradition since the ninth century. In the darkness of the church, lit only by candles, the faithful listen to the song of light and glory:

Rejoice, O earth, in shining splendor,

radiant in the brightness of your King!

Christ has conquered! Glory fills you!

Darkness vanishes for ever!

And, concluding:

May the Morning Star which never sets

find this flame still burning:

Christ, that Morning Star,

who came back from the dead,

and shed his peaceful light on all mankind,

your Son, who lives and reigns for ever and ever. Amen.

The Liturgy of the Word follows, consisting of seven readings from the Old Testament and two from the New Testament. These readings include the story of creation (Genesis 1 and 2), Abraham and Isaac (Genesis 22), the crossing of the Red Sea (Exodus 14 and 15), the prophet Isaiah proclaiming God’s love (Isaiah 54), Isaiah’s exhortation to seek God (Isaiah 55), a passage from Baruch about the glory of God (Baruch 3 and 4), a prophecy of Ezekiel (Ezekiel 36), Saint Paul on being baptized into Jesus Christ (Rom 6), and the Gospel of Luke about the empty tomb discovered on Easter morning (Luke 24:1-21).

These readings constitute an overview of salvation history and God’s various interventions into time and space, beginning with Creation and concluding with the angel telling Mary Magdalene and others that Jesus is no longer dead; "You seek Jesus of Nazareth, the crucified. He has been raised; he is not here." Through these readings "the Lord ‘beginning with Moses and all the prophets’ (Lk 24.27, 44-45) meets us once again on our journey and, opening up our minds and hearts, prepares us to share in the breaking of the bread and the drinking of the cup" (General Norms, 11).

Some of the readings are focused on baptism, that sacrament which brings man into saving communion with God’s divine life. Consider, for example, Saint Paul’s remarks in Romans 6: "We were indeed buried with him through baptism into death, so that, just as Christ was raised from the dead by the glory of the Father, we too might live in newness of life." Easter is in many ways the season of baptism, the sacrament of Christian initiation, in which those who formally lived in darkness and death are buried and baptized in Christ, emerging filled with light and life.

From the early days of the ancient Church the Easter Vigil has been the time for adult converts to be baptized and enter the Church. After the conclusion of the Liturgy of the Word, catechumens (those who have never been baptized) and candidates (those who have been baptized in a non-Catholic Christian denomination) are initiated into the Church by (respectively) baptism and confirmation. The faithful are sprinkled with holy water and renew their baptismal vows. Then all adult candidates are confirmed and general intercessions are stated. The Easter Vigil concludes with the Liturgy of the Eucharist and the reception of the Body, Blood, Soul, and Divinity of the Crucified and Risen Lord. For as Eastern Catholics sing hundreds of times during the Paschal season, "Christ is risen from the dead; by death He conquered death, and to those in the graves, He granted life!"

(This article was originally published in a slightly different form in the April 9, 2006, edition of Our Sunday Visitor newspaper.)

April 16, 2014

Now available: "Saint John Paul the Great: His Five Loves"

Through Ignatius Press:

Saint John Paul the Great: His Five Loves

by Jason Evert

Discover the five great loves of St. John Paul II through remarkable unpublished stories on him from bishops, priests , students, Swiss Guards, and others. Mining through a mountain of papal resources, Jason Evert has uncovered these many gems, offering a treasure chest brimming with the jewels of the saint’s life. After a brief overview of John Paul’s life, Evert explores in depth his five great loves: Young People, Human Love, The Eucharist, Our Lady, The Cross.

This work is intended to be catechetical, inspiring, and evangelical. By looking at what he loved and why, the goal is to help readers learn more about key aspects John Paul’s life and teachings, including Theology of the Body, Divine Mercy, Total Consecration, Eucharistic adoration, and redemptive suffering.

Woven throughout the book is an assortment of intriguing stories and facts that most Catholics don’t know about the saint, such as:

How the communists actually selected him as archbishop

How a priest stabbed him in Fatima, yet he continued with the liturgy

How one of Osama Bin Laden’s “best men” nearly murdered him in the Philippines

How he had conversations with the Virgin Mary

Rekindle your own faith by learning what captivated the heart of this great saint. Includes 8 pages of color photos.

Jason Evert has spoken about the Catholic Faith to more than one million people on six continents, and is the author of more than a dozen books, including Pure Faith, Theology of the Body for Teens, and How to Find Your Soulmate without Losing Your Soul. He and his wife Crystalina run the website chastityproject.com and live in Colorado with their children.

Praise for Saint John Paul the Great:

"Jason Evert offers readers an insightful, popular introduction to St. John Paul's life and loves."

- George Weigel, Author, Witness to Hope

“Jason Evert has synthesized the life and teaching of Pope John Paul II around the motives that mark a saint’s life: what great loves moved him to be the witness to the Gospel, the apostle to the modern world, a mystic who was also philosopher and pastor? Reading this book, those who knew him will find themselves smiling and nodding; those who never met him will come to know him.”

- Francis Cardinal George, Archbishop of Chicago

"Amid the great array of John Paul bios, this one stands out because of the evident love the author has for his subject. In this telling, love draws out new riches and makes a familiar story fresh and new."

- Fr. Michael Gaitley, MIC, Bestselling author, 33 Days to Morning Glory and Consoling the Heart of Jesus

Dr. Christopher Kaczor on big myths about love and marriage

Dr. Christopher Kaczor, author of The Seven Big Myths about Marriage: What Science, Faith and Philosophy Teach Us about Love and Happiness , was recently interviewed by Kathryn Jean Lopez, author of National Review Online:

, was recently interviewed by Kathryn Jean Lopez, author of National Review Online:

KATHRYN JEAN LOPEZ: Does anyone really believe “love is simple” — your first myth?

CHRISTOPHER KACZOR: Unfortunately, I believed this first myth until fairly recently! I suppose there are at least some other people who believe something like I did. I used to think that love was just a matter of good will. If I choose to do what helps another person, then I love that person. Once I learned more about the nature of love, I learned that love includes not only good will for the one you love but also appreciation for and seeking unity with the beloved. All forms of love (agape) involve all three aspects, and the forms of love are distinguished primarily in terms of the third characteristic, the diverse ways in which unity is sought.

LOPEZ: British prime minister David Cameron recently said that “love is love,” in welcoming same-sex marriage this month. How might you respond to such an assertion?

KACZOR: I’d say that marriage and love are related but that more than love alone is needed for a marriage. You could certainly have one man who loves four different women, but presumably this does not mean that a man should have a legal right to polygamy. Love can and does exist without legal recognition as marriage. ...

LOPEZ: You write, “Like any word, ‘marriage’ must be defined because, if marriage means anything and everything, then marriage means nothing.” What does marriage mean in America today?

KACZOR: We are in a great societal conversation today in the United States about the question, “What Is Marriage?” Some people hold that marriage is the comprehensive union of a man and a woman who have vowed unconditional love to each other for as long as they both shall live. Other people think of marriage as a partial union between two people (of whatever sex) that can be dissolved whenever either party wishes. Still other people — advocates for polygamy — think that marriage can be a union of more than two persons. Nevertheless, I think people of all three of these views can agree that there must be some kinds of relationships that are recognized as marriages and other kinds of relationships that should not be recognized as marriages. Everyone “draws the line” somewhere between what is marriage and what is not marriage.

LOPEZ: What is the most widespread myth about marriage?

KACZOR: The most widespread myth about marriage is probably that “cohabitation is just like marriage.” I cannot tell you how many of my students think this, and how many of them believe that living together prior to marriage will lower their likelihood of divorce. In the book, I point out that many studies indicate that cohabitation actually increases the likelihood of divorce, and that the longer a couple cohabits the more likely it is that they will divorce.

Read the entire interview on the National Review website.

Prayer as Turning Point Toward Christ

Prayer as Turning Point Toward Christ | Carolyn Humphreys, O.C.D.S. | HPR

The good news is that even though we sin, God loves us and wants us to return to him. With God’s grace, bad habits can be unlearned.

Ecclesia semper reformanda: The Church forever in need of reform. Because we are the Church, we are the ones who are ever in need of reform. We struggle with this until our dying day because the end of the road is not at the grave. Each choice we make reflects an individual effort toward reform, or a lack of it, and will impact the Church—and ultimately our eternal destination. How often do we think of this? How often do we consider the impact of our choices? How often does prayer undergird the process by which we evaluate our choices?

Jesus said either we are for him or against him. He gives all people the freedom to choose and they do so every day. The consequences of people’s choices support or hinder them from moving toward God and growing as human beings. Choices also affect an individual’s internal milieu fostering deep peace to deep torment. Each choice has an outcome that affects people’s relationships with God, others, and themselves.

Good choices increase our ability to love God and others. Bad choices distance us from this love. However, they can also bring us back to God if they result in a lasting change, such as alcoholics or drug users who find God during their rehab process. It has been repeatedly shown that we can learn from our mistakes when those mistakes teach us to make positive decisions.

Prayer helps us notice choices that have become automatic; made without thinking. Repeated poor choices become bad habits. Listening to too much news consumes quality time and often provokes anxiety. Lying to a loved one causes trouble. Taking another drink before driving is never smart. Sharing harmful gossip instead of remaining silent hurts others. Routinely watching degrading TV shows dulls the mind and dehumanizes one’s outlook. Glossing over a problem that needs immediate attention is procrastination. To continue to eat empty calorie foods instead of fruits and vegetables has its effect on health. Much time and energy is wasted on being a victim, reliving past mistakes, dwelling on failures or insecurities, or self-defeating ruminations. Is this pleasing to God who made us? There are endless examples of poor choices. Francis de Sales wrote, “We have freedom to do good or evil, yet to make the choice of evil is not to use, but to abuse our freedom.”

Our thinking is sharpened by daily prayer.

Carl E. Olson's Blog

- Carl E. Olson's profile

- 20 followers