Carl E. Olson's Blog, page 29

October 31, 2015

The saints are sealed, called, and saved by God

"Christ Glorified in the Court of Heaven" (1428-30) by Fra Angelico [WikiArt.org]

The saints are sealed, called, and saved by God | Carl E. Olson

A passage from The Apocalypse is read on the Solemnity of All Saints because it describes the reason we were created: to be holy ones

Readings:

• RV 7:2-4, 9-14

• PS 24:1BC-2, 3-4AB, 5-6

• 1 Jn 3:1-3

• Mt 5:1-12a

Many readers are understandably confused or puzzled when hearing a passage from the Book of Revelation. It is unfortunate, however, that many end up dismissing what they’ve heard. In so doing, they miss out on some of the most joyful passages of sacred Scripture. Yes, that's right—joyful.

Today’s first reading is a perfect example of such a passage. It is read on the Solemnity of All Saints because it describes the reason we were created. Using a multitude of references to the Old Testament, John the Revelator shows what it means to be a saint, a “holy one.” I wish to highlight three of the characteristics shared by all saints revealed in the seventh chapter of The Apocalypse. The word apokalypsis, by the way, refers to an “unveiling”—primarily of Jesus Christ, of course, but also of God’s fulfilled work of salvation and his plan for each of us.

The first characteristic of all the saints is they are sealed by God. Prior to judgment being sent from the throne room of heaven upon the wickedness of man, the servants of God are to be sealed, or marked, and thus set apart as holy. This imagery is drawn from the ninth chapter of Ezekiel, which describes the Lord commanding a mysterious “man clothed in linen” to go through Jerusalem and “put a mark upon the foreheads of the men who sigh and groan over all the abominations that are committed in it” (Ezek. 9:3-4). Those who loved God and who hated sin were saved; all others perished. The mark described by Ezekiel would protect the righteous Israelites from four rapidly approaching judgments, to be carried out by Babylon (another name used often in the Book of Revelation).

Jesus was set apart by the Father with a seal (Jn. 6:27). Those who are baptized into Christ are also marked, with the seal of the Holy Spirit, which is both familial and judicial in nature. Those marked by God belong to him; they are now of his household—the Church—and are under his authority and protection from eternal damnation (see Catechism, pars. 1295-6).

The second characteristic of saints, which builds on the first, is that they are servants and sons of God. Logic tells us it is only proper for man be a servant to his Maker. God’s love, however, reveals and imparts an astounding truth: man is called to be a son of God by grace because of the sacrificial death of the Lamb. As sons, the saints are joined in the communion of the Church, the divine house of God (1 Tim. 3:15; Heb. 3:5-6). An essential part of the service rendered by the saints is prayer, worship, and praise. “We know that God does not listen to sinners,” Jesus told his disciples, “but if any one is a worshiper of God and does his will, God listens to him” (Jn. 9:21).

The saints on earth and in heaven worship and praise God because of the third characteristic: they are saved from sin and death. Baptized into Christ, they rise with him to eternal life. This can be seen in the description of the Church triumphant, which is a great multitude of “every nation, race, people, and tongue,” wearing white robes and carrying palm branches.

“By robes he suggest baptism,” wrote Bishop Primasius (c. 560) in his commentary on The Apocalypse, “and by the palms the triumph of the cross. Since they have conquered the world in Christ, it may be that the robes signify the love which is given through the Holy Spirit…”

Having survived “the time of great distress,” saints enter into eternal joy. The final chapter of the Bible describes that joy. “There shall no more be anything accursed, but the throne of God and of the Lamb shall be in it, and his servants shall worship him; they shall see his face, and his name shall be on their foreheads” (Rev. 22:3-4). That is what it means to be saint; that is the reason we were created.

(This "Opening the Word" Scripture column originally appeared in a slightly different form in the November 1, 2009, edition of Our Sunday Visitor newspaper.)

On November: All Souls and the "Permanent Things"

On November: All Souls and the "Permanent Things" | Fr. James V. Schall, S. J. | Ignatius Insight

I.

A seminary in Ireland, now closed, was dedicated to the training of priests for foreign missions, for strange places such as California. It was called "All Hallows", that is, All Saints, November 1. Oxford University in England has a college called "All Souls," November 2. Taken together, all saints and all souls are designed to cover all of the final combinations of the human race except all the still living, who are waiting to join one or the other of the previous categories. Come to think of it, all "all saints" all have souls. What are left are all lost souls who, presumably, have already also made their final choices about how they are permanently to be.

Most of my relatives are buried in the Catholic Cemetery just at the edge of Pocahontas, a small county seat in rural northwest Iowa. My mother's grandparents, my grandparents on both sides of my family, my mother herself, and, I believe, all but one of her thirteen brothers and sisters are buried in this neat cemetery. Two of my father's brothers are also there; his other brother is a few miles east in the cemetery in Clare. Two of my father's four sisters are buried there, as well as numerous cousins and their families, though many are scattered in later years. My own father is buried in the cemetery in Santa Clara, and my brother in the cemetery in Spokane.

On the Second of November, many families, especially in small towns, decorate the graves with flowers, have Masses or prayers said for their deceased relatives, and in general remember them. In modern cities, I think, we are in danger of losing contact with the dead in our families and in our culture. Families move. Cremation changes things. There are so many of us. We do not have to be superstitious, of course. We believe in the immortality of the soul and the resurrection of the body. Our contact with cemeteries is designed to recall our very mortality, but also to remind us of what we hold about death and its place in our lives.

As we get older, we find that many more of our immediate family are dead than alive. We find friends gone. Such is our lot. To wish it otherwise, while not a totally unhealthy exercise, needs to be understood clearly. It is given unto every man once to die, thence the judgment, as it says in the Book of Maccabees. Death has become a hospital, not a home, thing. The dead body is a source of parts, to be somehow passed on to others. We think almost exclusively of the living, not of the dead.

We celebrate lives at funerals. We do not worry about souls and their fates. The elderly are a problem, even a social and political problem, not sources of wisdom. Cemeteries are often desired for the land they take up. Laws exist about how long cemeteries are to be kept intact. We still notice that many Latino and Asian families somehow take care of their own elderly at home, whereas with others this care is often passed on to various institutions and specialists. This may not be all bad, but we should reflect on it.

II.

Belloc's wonderful book, The Four Men, describes a walk he took in the English county of Sussex, from October 29 till All Souls' Day, 1902. As the four walkers reach the end of their walk, the old man, who, like the other three walkers, is Belloc himself, makes the following memorable farewell reflection:

There is nothing at all that remains: not any house; nor any castle, however strong; nor any love, however tender and sound; not any comradeship among men, however hardy. Nothing remains but the things of which I will not speak, because we have spoken enough of them already during these four days. But I who am old will give you advice, which is this: to consider chiefly from now onward those permanent things which are, as it were, the shores of this age and the harbours of our glittering and pleasant but dangerous and wholly changeful sea. When he had said this (by which he meant Death), the other two, looking sadly at me, stood silent also for about the time in which a man can say good-bye with reverence

I have always been moved by this haunting passage--nothing at all remains, the glittering and pleasant but dangerous and wholly changeful sea, the time in which a man can say good-bye with reverence.

In the Breviary, for the Feast of All Souls, the Church includes a very powerful passage from St. Ambrose about the death of his brother, Satyrus. This is a particularly significant reflection on death. Ambrose tells us that Christ did not need to die if he did not want to. This position does not mean that Christ was a sort of suicide. It means that, as God, nothing could happen to Him without His own will, which acted in free obedience to the Father. Thus the obvious question arises about why the Father might require this obedience?

To this question Ambrose adds that Christ could have found no better means to save us than by dying. We can and do try to imagine a better way. We come up with alternatives. Much of ancient and modern thought is an attempt to find a suitable alternative to explain why the human condition is as it is. This same thought is quite disconcerted with the notion that the Christian explication might, after all, be true. The connection is between Christ's death and the saving of mankind. The former was necessary if the latter were to be accomplished, while protecting both divine and human liberty in the events leading to a proper salvation.

But why does mankind need saving? Why cannot it save itself? Ambrose continues, "death was not part of nature; it became part of nature." This sentence must be examined. Clearly, it states that a finite being like man, the mortal, is naturally slated to die. This view, that death is not part of nature, goes against all our thinking about what finite creature like ourselves are. But such a mere mortal, born to die, never existed in fact.

From the beginning of God's intention in creation, the man who did exist was destined to a supernatural end, to participation in the inner life of God. This was something beyond what it is to be a human being as such. This possibility was due to something over and above what was naturally due to man. What we know as "original sin", that necessary but perplexing doctrine, is the reason why the initial relation of man to his end did not come about. This fall, as we call it, meant that death subsequently became part of nature, in Ambrose's words.

We are all thus so interconnected that the actions of one person can affect all the others. If this connection with others would not be possible, men would be naturally isolated from one another, not social animals. No one could stand such a solitary life. Ambrose continues, "God did not decree death from the beginning." In the beginning, to use the first words of Genesis, God decreed no death for the particular man He created and for his descendants. How did God prescribe death then? Ambrose says that He prescribed it in the actual context in which He found it, that is, in the context of Adam and Eve's choice, as a remedy.

What a remarkable insight! But a remedy? Death is a remedy? What can this mean? How could precisely death remedy anything? Is this merely irony? It seems, in this context, that only life could be a remedy. But remember death is proposed as a remedy for what has happened as a result of the fall, as a result of sin--all sin. Thus, something connected with the essence and nature of sin and its consequence justifies God in proposing the odd notion that death is a remedy for what has gone wrong in the human condition by man's own choosing.

III.

Ambrose gives the following explanation of our fallen situation. He takes it to be based on something we all recognize. Human life was condemned because of sin to unremitting labor and unbearable sorrow and so began to experience the burden of wretchedness. These are almost the same words used in Genesis about what would happen to Adam and Eve if they ate of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, that is, if they chose to make up their own laws.

The origin of this wretchedness among us, about which wretchedness all the subsequent history of mankind attests, is not God. We are created good. We were offered a life with no death, but such a life had to be chosen. Otherwise, it would have been imposed on us. Hence, it would not really be ours. Without some remedy that we could not concoct for ourselves, this wretchedness would go on and on, even midst our dying. Remember, the original purpose of God in creating us--that we be offered the inner life of God as our final destiny--never changed from the beginning.

The question now became, how would this remedy work? There had to be a limit to its (wretchedness') evils. God is not defeated by evil, but He cannot act as if it did not happen. John Paul II, in one of his last books, maintained that what limits evil is "the divine mercy." That is, God would only allow evil to occur insofar as He could, in spite of it, lead things back to His original purpose.

Ambrose then explains the terms of what must be done. Death had to restore what life had forfeited. Again this is a thoroughly remarkable statement. What had life forfeited? Well, it forfeited the not dying that was originally offered as a gift over and beyond what human nature was in itself. It also forfeited thereby the original way that mankind was offered to participate in the inner life of the Godhead, which is, in itself, a life of infinite love that we describe as Trinity. No reason existed in God why He had to create anything in the first place. He had no deficiency or loneliness. Creation was in freedom, not necessity.

What then does death do? That is, supposing no redemption, what will happen among our kind as a result of their own sinning and its consequences on others? Without the assistance of grace, immortality is more of a burden than a blessing. What does Ambrose say here? First, he implies that we cannot redeem ourselves. We need a redeemer who is not just human, but still human. We need someone like unto us in all things "except sin," to recall Paul's words.

The soul, as the Greeks taught, is, however, itself naturally immortal. But that is an eerie kind of life from which also we need to be redeemed. But why exactly would immortality--which means, whatever its moral condition, the continuation forever of the soul without the body--be a burden

First, we are not just souls and are not intended to be. Aristotle had already hinted at something of this issue in his tractate on friendship, when he wondered if we would want our friend to be a god, that is, a pure spiritual being or soul? No, he thought, we want to be what we are, beings complete with bodies and souls. Thus, it would be wretched both to continue in a disordered life, even as a soul, and as an incomplete life without a body.

The immortality of the soul is a Greek teaching, though Christians also hold it to be true. The Christian use of the immortality of the soul is to explain how we are the same person who dies and who rises again. Without this connection provided by immortality, it is senseless to talk of personal continuity and even less of resurrection. What Ambrose says is that we need grace to accomplish this reunion. What we also need is someone who actually dies with the power to raise us up. And someone actually needs to atone for our sins. This is why Christ is central in any discussion of souls on All Souls Day.

Our souls, or our minds as the active powers of our souls in knowing the order of things, do know permanent things. They know what is. And they know that they know. Socrates, at the end of his trial, figured that since his soul was immortal, he would continue to do what he always did, to speak and converse about the highest things with his friends. We do not disagree with this possibility. But we add that we also converse with God, become friends with God, not by our own power, but by grace through the death of Christ which destroyed the death that was the punishment for sin.

Thus, All Saints' Day and All Souls' Day give us much to think about. On both days, we recognize that salvation includes keeping human beings to be what they are even in redemption, or especially in redemption. On All Souls' Day we recall the dead, we realize that death is also given to us as a remedy. It is a remedy for our sins, for our lives in the midst of sins' consequences, the wretchedness of lives and existence that merely goes on and on. The remedy is also a return to what is the initial purpose in creation. That is, we are still enabled, even in the midst of sin and death, freely to choose what we shall be. Not even God can make this latter choice for us. On this choice, and its implications, the real drama of the universe consists.

As Ambrose said, Christ could have found no better way to save us than by dying. How long does it take to say good-bye with reverence? The real answer to this question is that we are not ultimately intended to say "good-bye." This is why we were originally created without death. And this is why, when we are redeemed on the Cross, we are redeemed by One who says, succinctly, that "I no longer call you servants, but friends." The friendship of man with God now includes death. But this death is now a remedy for not the cause of, our wretchedness. Perhaps these are some of the things we can think about as we visit our cemeteries in early November, on All Hallows' Day and on All Souls' Day. When we walk in our cemeteries we are reminded that, among the ultimately permanent things, we ourselves are included. Such is the meaning of these November days.

This essay originally appeared on Ignatius Insight on October 31, 2006.

Related Ignatius Insight Essays and Articles:

• Creation, Salvation, and the Mass | Fr. James V. Schall, S.J.

• Death, Where Is Thy Sting? | Adrienne von Speyr

• The Religion of Jesus | Blessed Columba Marmion

• Purgatory: Service Shop for Heaven | Reverend Anthony Zimmerman

• Reincarnation: The Answer of Faith | Christoph Schönborn

• Hell and the Bible | Piers Paul Read

• The Question of Hope | Peter Kreeft

• The Brighter Side of Hell | Fr. James V. Schall, S.J.

• Socrates Meets Sartre: In Hell? | Peter Kreeft

• Are God's Ways Fair? | Ralph Martin

October 29, 2015

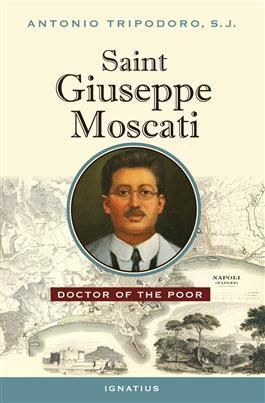

Moscati’s amazing story of medical and spiritual devotion to the poor is a shining witness for the dignity of all human life

San Francisco, October 29, 2015 – This is the compelling and inspirational true story of a medical doctor  who lived in the 20th century and is now a canonized saint. Giuseppe Moscati, physician, medical

who lived in the 20th century and is now a canonized saint. Giuseppe Moscati, physician, medical

researcher, and teacher in Naples, Italy, came from an aristocratic family and devoted his medical career to serving the poor. He was also a medical school professor, and a pioneer in the field of biochemistry whose research led to the discovery of insulin as a cure for diabetes.

Moscati regarded his medical practice as a lay apostolate, a ministry to his suffering fellowmen. Before examining a patient or engaging in research he would place himself in the presence of God. Moscati treated poor patients free of charge, and would often send them home with an envelope containing a prescription and a 50-lire note. He could have pursued a brilliant academic career, taken a professorial chair and devoted more time to research, but he preferred to continue working with his beloved patients and to train dedicated interns.

To his many medical students he taught by the witness of his life to practice their profession in a spirit of service, because "suffering should be treated not as just pain of the body, but as the cry of a soul, to whom another brother, the doctor, runs to with the ardent love of charity . . . They are the faces of Jesus Christ, and the Gospel precept urges us to love them as ourselves."

"This man whom we will invoke as a saint of the universal Church appears to us as a concrete realization of the ideal of the Christian layman. Giuseppe Moscati, head physician of a hospital, a renowned researcher, a university instructor of human physiology and chemistry, performed his many and various tasks with all the commitment and seriousness that the practice of these delicate lay professions requires."

- Pope John Paul II, Homily at the Canonization of Giuseppe Moscati

What Others Are Saying

"A fascinating account of a doctor who cared for the body as well as the soul of the sick. His exemplary life inspires us to strive for holiness and love for the poor and suffering. Highly recommended!"

— Donna-Marie Cooper O'Boyle, EWTN TV Host, Author, The Kiss of Jesus

"God gives us saints like Dr. Moscati as gifts to pull us toward Him."

— Marcus Grodi, EWTN Host, The Journey Home

"The life of St. Moscati highlights in an outstanding way what the saint himself called the 'sublime mission' of those who serve the sick. His example of deep Eucharistic devotion, personal poverty and self-denial, chastity, and of service to the poor is a source of great inspiration for us in living our Christian vocation."

— Sr. M. Regina van den Berg, F.S.G.M., Author, Communion with Christ

About the Author:

Antonio Tripodoro S.J., a Jesuit priest, has been a leader in promoting devotion to Saint Giuseppe Moscati since his canonization in 1987. He has taught philosophy and history, and is the editor of Il Gesll Nuovo, the official publication about devotion to Moscati. He is the author of the books Giuseppe Moscati: Il medico santo di Napoli, and Preghiere in onore di san Giuseppe Moscati, a collection of prayers. He carries on a worldwide correspondence regarding devotion to Saint Giuseppe Moscati.

Product Facts:

Title: SAINT GIUSEPPE MOSCATI: Doctor of the Poor

Author: Antonio Tripodoro, S.J.

Release Date: October 2015

Length: 181 pages

Price: $16.95

ISBN: 978-1-58617-945-8 • Paperback

Order: 1-800-651-1531 • www.ignatius.com

On a new Saint and negative press

The gravesite of St. Junipero Serra in Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo (Photo: Dale Ahlquist)

On a new Saint and negative press | Dale Ahlquist | CWR

The canonization of Fr. Junipero Serra should have been a cause for great rejoicing for all Catholics and for the people of California, and, well, for everybody else. But it wasn't.

I recently returned from making the rounds in the San Francisco Bay area and beyond, where I gave some talks on my favorite writer. While there, I ventured down the coast a ways to visit the grave of one of the world's newest saints—and the first saint ever canonized on U.S. soil—Father Junipero Serra. He is buried beneath the altar of the Mission San Carlo Borromeo del Rio Carmelo, also known as the Carmel Mission Basilica.

His canonization should have been a cause for great rejoicing for all Catholics and for the people of California, and, well, for everybody else. Instead, what little publicity it got was much more negative than positive.

Instead of being portrayed as a brave and compassionate missionary, who brought the love of God and many other good things to souls along the California coast, he is being condemned as an oppressor of the native peoples and a symbol of European Imperialism. The portrait is a little unfair. And a little inaccurate. (For those not familiar with irony, when I say “a little” I really mean “gigantically.”)

For most of the last two hundred plus years, this Franciscan priest had a good reputation among Catholics and non-Catholics alike. Considered “The Man Who Founded California” the state honored him with a statue in the U.S. Capitol. He founded the first nine of twenty-one Franciscan missions in California, including the ones that eventually became the cities of San Diego and San Francisco. He started the first library in California. The many Serra Clubs across the country are named for him.

But then if you don't like history, one of the simplest solutions is to revise it. G.K. Chesterton expresses the idea that God alone knows the future, but only a historian can re-write the past. Political agendas replaced the historical record, and Fr. Serra's great accomplishments were given a coat of tarnish. Without the benefit of facts, he has been condemned as a racist and a slaver, utterly false accusations. At best, what was once high praise has been replaced with the suggestive word, “controversial.”

In the meantime, the Catholic Church made him a saint.

And perhaps the tide is turning back toward the truth.

October 28, 2015

"Apocalyptic Fiction": An interview with novelist Michael O'Brien

Apocalyptic Fiction | Rose Trabbic | IPNovels.com

An interview with Michael D. O’Brien about his new novel, Elijah in Jerusalem, the sequel to his 1996 debut novel, Father Elijah: An Apocalypse

Michael D. O’Brien is a best-selling novelist, an insightful social critic, and an acclaimed painter. In 1996 Ignatius Press published his debut novel, Father Elijah: An Apocalypse, a powerful story of a Carmelite priest’s confrontation with the Antichrist. Since then, Ignatius has published ten more of his novels. His writing has been compared to Dostoevsky by Peter Kreeft, and has been praised by the late Sheldon Vanauken, who said of Father Elijah: “I’ve read thousands of books, and this is one of the great ones. I hope tens of thousands read it, and are shaken as I have been.”

It has been nearly twenty years since the publication of Father Elijah. It’s now that we return to the story of Elijah Schäfer: priest, Holocaust survivor, and witness to the end times. Rose Trabbic interviewed Michael O’Brien about the new novel Elijah in Jerusalem for the Ignatius Press Novels blog.

In the preface to Elijah in Jerusalem you wrote, “To presume that we have received in advance a precise decryption of the symbolic prophecies in the book of Revelation – a route map or survivalist manual, as it were – is to weaken our faculty of discernment and our openness to the guidance of the Holy Spirit and the angels.” Why did you feel the need to write this warning in the preface?

O’Brien: World-angst is in the very atmosphere we breathe daily. The apocalyptic sense saturates the consciousness, and subconscious, of contemporary mankind. It manifests in a variety of ways, for example in the tsunami of disaster films and also in the neo-horror films which corrupt the meaning of the supernatural. It’s also visible in the proliferation of people claiming to be mouth-pieces for God. My purpose in writing a cautionary introduction to the novel was mainly to warn believing Christians against this particularly dangerous form of apocalypticism. Because my novel deals with apocalyptic themes in an imaginative way, I did not want any readers treating the story as a kind of “prophetic” foretelling of the future, adding it to the thousand voices proclaiming wildly diverse scenarios of the future.

Do you reject private revelation?

O’Brien: No, I surely do not. However, I maintain that in this field of the spiritual life we must always exercise particularly careful discernment. While I respect private revelation that is tested and approved by legitimate religious authority, I am concerned about the way many deeply devout people have fallen into a kind of neo-gnostic consumption of the locutions of seers and visionaries, indiscriminately, and to the degree that it becomes an insatiable appetite. All too easily this leads to displacing the Gospels and the teachings of the Church with a pseudo-Gospel, an End-Times Gospel. In my novel, both authentic and false private revelations play a role; the authentic consoles and strengthens God’s servants, the false sows confusion among the most devout of the Lord’s followers. Both are indeed present in our times—at the very moment in history when we need to be most united in our resistance to evil.

In Elijah in Jerusalem, the Antichrist emerges as the world leader, and Father Elijah is sent to rebuke him and call him to repentance. One of the Antichrist’s important platforms is to erase all differences with religions so that there will be peace. Why is this a dangerous and false illusion?

October 27, 2015

A Black Legend Refuted

Pope Pius XII is pictured at the Vatican in a file photo dated March 15, 1949. (CNS file photo)

A Black Legend Refuted | Fr. John Jay Hughes | CWR

Mark Riebling's Church of Spies: The Pope’s Secret War Against Hitler is a beautifully written book which not only defends Pius XII but utterly demolishes the Black Legend in intricate and meticulously documented detail

Of the eight Popes who shepherded the Church from 1903 to century’s end, none is so hotly disputed as Pius XII, who reigned from March 2nd, 1939 until his death on October 9th, 1958. At issue is the Pope’s alleged “silence” in the face of the Holocaust. His defenders point out that in reality he was not silent. At the start of World War II Pius authorized Vatican radio to broadcast reports of Nazi atrocities in Poland. These ceased only at the urgent plea of victims reporting that the broadcasts intensified their sufferings.

In 1942 the Pope’s Christmas message spoke of “the hundreds of thousands who, through no fault of their own, and solely because of their nationality and race, have been condemned to death or progressive extinction.” Dismissed by his latter day critics as too vague to be understood, the Pope’s words were well understood by the Nazis, who called them “one long attack on everything we stand for. Here he is clearly speaking on behalf of the Jews ... and makes himself the mouthpiece of the Jewish war criminal.” The New York Times also understood, commenting: “This Christmas more than ever [Pope Pius XII] is a lonely voice crying out of the silence of a continent.”

At the war’s end Golda Meier (later Israel’s Prime Minister), Albert Einstein, the World Jewish Congress, the American Jewish Committee and many other Jewish voices applauded Pius for doing what he could to rescue Jews: by providing life saving travel documents, religious disguises, and safekeeping in cloistered monasteries and convents, including the Pope’s own summer residence at Castel Gandolfo, where Jewish babies were born in the Pope’s own bedroom. The Israeli diplomat and scholar Pinchas Lapide commented: “No Pope in history has been thanked more heartily by Jews.” At the Pope’s death in October 1958 the New York Times took three days to print tributes to Pius from New York City rabbis alone.

The chorus of praise fell silent overnight in 1963 with the publication of a pseudo-historical stage play, The Deputy, by a former junior member of the Hitler Youth, Rolf Hochhuth.

October 26, 2015

Calling Men to a Catholic Vision of Male Spirituality

Deacon Harold Burke-Sivers, author of "Behold the Man: A Catholic Vision of Male Spirituality" (Ignatius Press, 2015)

Calling Men to a Catholic Vision of Male Spirituality | CWR Staff | Catholic World Report

"Catholic men are destroying themselves by their own free-willed choices," says Deacon Harold Burke-Sivers, whose book Behold the Man focuses on Christ crucified, covenantal love, and fatherhood

Deacon Harold Burke-Sivers, known worldwide as the Dynamic Deacon, is a powerful speaker who has presented talks on marriage, family, and men's spirituality all over the world. He is a passionate evangelist and preacher with a no-nonsense approach to living and proclaiming the Catholic faith. Deacon Burke-Sivers holds a bachelor’s degree from the University of Notre Dame and a master of theological studies from the University of Dallas. He hosts his own weekly broadcast, From the Rooftops, on Radio Maria, and is the host of several popular series on EWTN television, including Behold the Man: Spirituality for Men. He and his wife Colleen have four children, and live in Portland, Oregon.

Deacon Burke-Sivers recently spoke with Carl E. Olson, editor of Catholic World Report, about his new book, Behold the Man: A Catholic Vision of Male Spirituality, published by Ignatius Press.

CWR: You participated last month in the World Meeting of Families as a speaker and also by assisting at Mass. What did you talk about? And what was your experience like at the event?

Deacon Harold Burke-Sivers: My topic at the World Meeting of Families was “Mary of Nazareth: The First Disciple and Mother of the Redeemer”. A disciple is one who hears, accepts, and puts into practice in their life every day the teachings of Jesus Christ and his Church. I talked about how the Blessed Virgin Mary was the quintessential example of what it means to be a disciple: to listen to God’s voice, allow that voice to change your life, and then follow God with your whole being in the obedience of faith. Mary exemplifies how our response to God’s invitation to life-giving communion reflects our trust in his love for us.

I also pointed out that Mary was the first monstrance, the first vessel that held—in the tabernacle of her womb—the body, blood, soul, and divinity of Jesus Christ. Her first impulse was to visit her kinswoman Elizabeth, which was the first Eucharistic procession. After receiving the Eucharist at Mass, we are sent forth to be “Eucharist” to the world, to tell people about our relationship with Jesus Christ. In this sense, whenever we receive the Eucharist, we become “pregnant” just as Mary was. Our mission, then, is to give life to Christ by going forward into the world and witnessing to the truth of our faith so that people can encounter the living God in us and through us.

I had a great time at the World Meeting of Families. It was wonderful to see such joy, enthusiasm, and love of the faith from families around the world. Many apostolates and ministries that are doing incredible work in the area of marriage and family life were also represented. The family is under assault by an increasingly hedonistic culture, and it was inspiring to see families looking to strengthen and deepen their commitment to each other and to the Catholic faith.

CWR: What are some of the positive signs you see in the Church regarding family life and men’s spirituality?

Continue reading in the CWR site.

October 21, 2015

The Wisdom of "Humanae vitae" and the Pastoral Care of the Family

A tapestry of Blessed Paul VI hangs from the facade of St. Peter's Basilica during his beatification Mass celebrated by Pope Francis in St. Peter's Square at the Vatican Oct. 19, 2014. (CNS photo/Paul Haring)

The Wisdom of Humanae vitae and the Pastoral Care of the Family | Stephan Kampowski and David S. Crawford | CWR

What the Church, the Body of Christ, has called true and good yesterday cannot possibly become false and burdensome today

As they are gathered in Rome to discuss the “Vocation and Mission of the Family in the Church and the Contemporary World,” the Synod Fathers ask themselves how to find new impetus for the pastoral care of the family. For this purpose it is important precisely to individuate the challenges that confront the family in today’s societies. At least according to some sociologists, the biggest challenge is the sexual revolution (cf. M. Eberstadt, “The New Intolerance”, First Things, March 2015), whose principal characteristic is the separation between sexuality and procreation. Living in a post-revolutionary world, we often find it difficult to appreciate the radicalness of this revolution and its heavy impact on how people today live their sexuality, their marriages and their family life.

The magisterial pronouncement that most strongly proposes an alternative to the sexual revolution is Bl. Paul VI’s encyclical Humanae vitae. In the working document for this year’s Synod, one can find two opposite attitudes toward this document. Paragraph 137 expresses a pragmatic approach that takes its orientation from the contemporary world. While it praises the wisdom of Humanae vitae, it fails to summarize its main content, and with a pre-Conciliar casuistry it empties the encyclical of its normative value (cf. D. Crawford – S. Kampowski, “An Appeal”, First Things, September 9, 2015). In the preceding paragraph 49, on the other hand, we read that “Paul VI, in his Encyclical Humanae Vitae, displayed the intimate bond between conjugal love and the generation of life.” One could say that this is indeed the document’s principal argument which it is well worthwhile expanding upon, as we will do here in what follows.

Marital Love: The Basis of the Norm

In paragraph 14 Humanae vitae expresses a norm against sexual acts that are deliberately rendered sterile (this is what it means by “contraception”), calling them intrinsically dishonest. In support of this norm it proposes a fundamental thesis whose foundations we will examine in a moment. The thesis is the following: a contraceptive sexual act can never qualify as an act of conjugal love. This is the essential meaning of the so-called “inseparability principle” proposed by the encyclical, according to which there is an inseparable connection between the unitive and the procreative significance of the marital act (HC 12). If this is the case, then it will be clear how contraceptive intercourse violates the sixth commandment, the main point of which is precisely that sexual intercourse is for marital love alone. In other words, the contention is that in contraceptive intercourse a man has sex with his wife without treating her as his wife; a woman has sex with her husband without relating to him as her husband, so that, whatever it is they are doing, they are not performing an act of spousal love.

Now what is the basis of this claim? To see this, we need to ask what it takes for a sexual act to be an act of spousal love. A number of requirements need to be fulfilled. First, quite obviously, it needs to be a sexual act performed by spouses, that is, by a man and a woman who have joined their lives through a public promise of mutual fidelity, sexual exclusivity and openness to the generation and education of children. By making this pledge, the two unite in marriage, which is the institution of marital love, which, in turn, is a love with a mission: “the most serious role [munus=an office with its related duties] of parenthood” (cf. HV 1). This mission of generating and educating children is what distinguishes a marital friendship from other kinds of friendship. As the Second Vatican Council says, “By its very nature the institution of marriage and married love are ordered to the procreation and education of the offspring and it is in them that it finds its crowning glory” (GS 48). The love proper to husband and wife is thus one that has a particular mission and with that a peculiar comprehensiveness. As there is no greater union two people can achieve on earth than being the father and the mother of each other’s children, so there can hardly be a greater expression of love than saying to the other, “I want you to be the mother/the father of my children.” In this sense, what it means to be a woman’s husband is to be the potential father of her children. What it means to be a man’s wife is to be the potential mother of his children. The fact that the man and the woman look at each other in this manner in no way implies that they are instrumentalizing each other in view of procuring offspring. It only means that marital love is ordered to forming a family, which is the aspect under which a marital friendship is specifically different from all other kinds of friendships.

A second condition a sexual act needs to fulfill in order to be an act of marital love is that it is in itself apt for procreation.

October 19, 2015

Intrinsic Evils, Final Realities, and the Synod

Pope Francis speaks at an event marking the 50th anniversary of the Synod of Bishops in Paul VI hall at the Vatican Oct. 17. (CNS photo/Paul Haring)

Intrinsic Evils, Final Realities, and the Synod | Dr. Samuel Gregg | CWR

As St. Pope John Paul II's "Veritatis Splendor" reminds us, the idea that there are intrinsically evil acts has always been central to Catholic ethics. Without it, Catholic morality would cease to be Catholic.

It was inevitable. Any discussion about marriage and the family during a synod of Catholic bishops was always going to involve questions of morality. Just as the furor around Humanae Vitae was always about much more than contraception, so too do various proposals presented to the 2015 Synod unavoidably touch on the Catholic understanding of the moral life.

One phrase that has received much attention before and around the deliberations of the Synod fathers is that of “intrinsically evil acts.” To be clear, there are no intrinsically evil persons. There are sinful acts and sinners: i.e., all of us. But no human being is by nature intrinsically evil. The Church, however, has always taught that there are certain actions which by their very nature—or, more precisely, by reason of their object—are incapable of being ordered to the good and whose illicitness admits of no exceptions. The most recent authoritative declaration of this truth may be found in Saint John Paul II’s 1993 encyclical Veritatis Splendor. This mentioned intrinsically evil acts no less than sixteen times. Nor is there any question that the truth about such acts plays directly into several important subjects being addressed by the Synod.

Old Debates

As Veritatis Splendor and the many sources which it references—ranging from the solemn pronouncements of popes to church councils (including Vatican II), numerous Church Fathers, the witness of the saints and martyrs, and the Hebrew and Christian Scriptures—remind us, the idea that there are intrinsically evil acts has always been central to Catholic ethics. Without it, Catholic morality would cease to be Catholic.

In the years leading up to and after Humanae Vitae, however, some Catholic moral theologians—most notably, the German Jesuit who taught moral theology for decades at the Pontifical Gregorian University, Father Josef Fuchs—tried to develop theories clearly aimed at marginalizing, if not effectively denying the truth of intrinsically evil acts. Among the most prominent was the claim that an act could only be determined as good or evil in light of what they called “a total state of affairs.”

The totality to be considered included not just all the intentions underlying and circumstances surrounding an act, but also what Father Fuchs called “all the goods and evils in an act.” On this basis, one would evaluate not only, to cite Father Fuchs, “whether the evil or the good for human beings is prevalent in the act,” but also “the hierarchy of values involved and the pressing character or urgency of certain values in the concrete.”

If such an evaluation sounds impossible, that’s because it impossible. No human being can possibly know all such things. Nor can anyone estimate in any coherent manner the different degrees of good and evil in an act along the lines suggested by Father Fuchs and others. By what standard do we calculate the amount of good and evil in an act without collapsing into some sort of utilitarianism? And utilitarianism means essentially arbitrary (i.e., unreasonable) judgments as one seeks to measure the immeasurable, as numerous secular philosophers such as Sir Bernard Williams have observed ever since Jeremy Bentham published his Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation in 1789.

Back to the Synod

Lest this seems like simply revisiting old—and settled—questions, the topic of intrinsically evil acts has direct relevance for several matters addressed by the Synod fathers.

October 17, 2015

No Cross, no Kingdom. Know the Cross, know the Kingdom.

"Crucifix" (1272) by Bencivieni di Pepo Giovanni Cimabue, in San Domenico churce in Arezzo, Italy [WikiArt.org]

A Scriptural Reflection on the Readings for Sunday, October 18, 2015 | Carl E. Olson

Readings:

• Isa 53:10-11

• Ps 33:4-5, 18-19, 20, 22

• Heb 4:14-16

• Mk 10:35-45

“No pain, no gain.” The well-known saying became popular among exercise enthusiasts in the 1980s. It was a motto for those who knew from experience that peak physical fitness requires perspiration, pain, and commitment. Variations of the sweaty slogan have been traced back to the seventeenth-century English poet Robert Herrick, and Ben Franklin, in the 1734 edition of Poor Richard's Almanack, wrote: “There are no gains, without pains...”

None of those sloganeers, I’m guessing, had the Passion and death of Jesus Christ in mind. But it fits, even if only as a introductory summary. And today’s Gospel could be given a similar slogan of sorts: “No Cross, no Kingdom.”

The conversation between Jesus and the sons of Zebedee, James and John, is a bit unsettling. It should certainly surprise anyone who thinks the disciples were dutifully pious saints from the very beginning, or simply robotic “yes-men” foils for Jesus. “Teacher,” they boldly—even impatiently and demandingly—declared to Jesus, “we want you to do for us whatever we ask of you.”

How audacious! My initial thought is, “Who do they think they are? Don’t they know who they are talking to?” Then, after further reflection, I have to admit how often I have approached Jesus in the same way, making demands in the guise of thinly veiled impatience. I need this done now, God! I want an answer immediately—and here’s the answer I expect!

Of course, God wants us to come to him with our problems and fears. But there is an essential difference between approaching God with humble trust and telling him, “Do what I ask of you!” The correct approach recognizes who we are in the light of God’s revealed truth and love. “For me,” wrote St. Thérèse of Lisieux, whose parents will be canonized today by Pope Francis, “prayer is a surge of the heart; it is a simple look turned toward heaven.” James and John looked toward heaven, not with the simple humility of gratitude, but with a selfish hunger for personal glory.

They wanted to be rulers and sons of God, seated on the right and left hands of the Lord. Perhaps they had in mind the well-known words of the Psalmist: “The LORD says to my lord: ‘Sit at my right hand, till I make your enemies your footstool’” (Ps. 110:1). Jesus provided the necessary reality check: “You do not know what you are asking.” When we make demands of God, it indicates that we have lost sight of who we are and what God desires us to be. This is why the prayer given by Jesus to his disciples states, “Thy kingdom come, thy will be done…”

It is one thing to follow a teacher; it is quite another to follow the Son of God to the Cross. As we heard in last week’s Gospel, the rich young ruler could not follow Jesus because of his attachment to riches. Likewise, all of us struggle with burdens, baggage, and desires that threaten to keep us from the Cross, or tempt us to come down from it. As someone dryly observed, “The only problem with a living sacrifice is it wants to crawl off the altar.”

Jesus asked his disciples if they could drink the cup he would drink. Throughout the Old Testament the cup often symbolized God’s judgment, and of the death—ultimately spiritual in nature—waiting the unrepentant wicked. The only man who didn’t deserve to drink the cup was the sinless God-man. But “through his suffering,” God proclaimed through the prophet Isaiah, “my servant shall justify many and their guilt he shall bear.” Willing to drink the deadly cup, the risen Lord and great high priest now offers the life-saving cup of his blood, the cup of the new and everlasting covenant which anticipates the feast of the coming Kingdom (CCC 2837, 2861).

“Apart from the cross,” St. Rose of Lima said, “there is no other ladder by which we may get to heaven” (cf. CCC 618). No Cross, no Kingdom. Know the Cross, know the Kingdom.

(This "Opening the Word" column originally appeared in the October 18, 2009, edition of Our Sunday Visitor newspaper.)

Carl E. Olson's Blog

- Carl E. Olson's profile

- 20 followers