Carl E. Olson's Blog, page 26

December 10, 2015

What Makes the Church Grow?

Pope Francis leads a ceremony to open the Holy Door as the begins the Holy Year of Mercy before a Mass with priests, religious, catechists and youths at the cathedral in Bangui, Central African Republic, Nov. 29. (CNS photo/Paul Haring)

What Makes the Church Grow? | Bishop Robert Barron | The Dispatch at CWR

While Catholicism is withering on the vine in many European countries, the center of gravity for Catholicism has shifted dramatically to the south, especially to the African continent

Just recently on the website maintained by the episcopal conference of Germany there appeared an editorial concerning Pope Francis's apostolic visit to Africa. As many have pointed out, the piece was breathtaking in its arrogance and cultural condescension. The author's take on the surprisingly rapid pace of Christianity's growth on the "dark continent" (his words)? Well, the level of education in Africa is so low that the people accept easy answers to complex questions. His assessment of the explosion in vocations across Africa? Well, the poor things don't have many other avenues of social advancement; so they naturally gravitate toward the priesthood.

What made this analysis especially dispiriting is that it came, not from a secularist or professionally anti-religious source, but precisely from the editor of the official webpage of the Catholic Church in Germany. It is no accident, of course, that the article appeared immediately in the wake of a very pointed oration of Pope Francis to the hierarchy of Germany, in which the Holy Father indicated the obvious, namely, that the once vibrant German Catholic Church is in severe crisis: its people leaving in droves, doctrine and moral teaching regularly ignored, vocations disappearing, etc. Thus it might be construed as a not so subtle shot across the Papal bow.

But it was born too, I think, of an instinct that is at least a couple of hundred years old that northern Europe -- and Germany in particular -- naturally assumes the role of teacher and intellectual leader within the Catholic Church. In the nineteenth century, so many of the great theologians were Germans: Drey, Döllinger, Mohler, Scheeben, Franzelin, etc. And in the twentieth century, especially in the years just prior to Vatican II, the intellectual heavy-weights were almost exclusively from northern Europe: Maritain, Gilson, Congar, de Lubac, Schillebeeckx, Bouyer, Rahner, von Balthasar, Ratzinger, Küng, etc. Without these monumental figures, the rich teaching of Vatican II would never have emerged.

But something of crucial importance has happened in the years since the Council. The churches that once supported and gave rise to those intellectual leaders have largely fallen into desuetude.

December 9, 2015

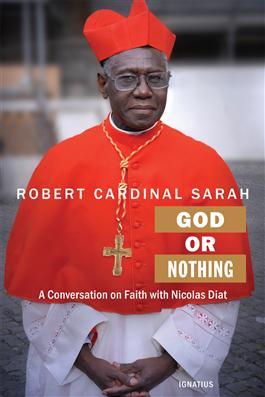

Cdl. Sarah: “Without God, there is nothing but wars, division, and bewilderment”

Cardinal Robert Sarah

Cdl. Sarah: “Without God, there is nothing but wars, division, and bewilderment”

“The real crisis that our world is going through now is not essentially economic or political, but a ‘crisis of God,’” says prefect of the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments.

The following remarks were delivered by Cardinal Robert Sarah at the November 20 presentation in Rome of his book God or Nothing , published in English by Ignatius Press and translated by Michael J. Miller. Miller also translated Cardinal Sarah’s speech for CWR.

, published in English by Ignatius Press and translated by Michael J. Miller. Miller also translated Cardinal Sarah’s speech for CWR.

***

Allow me first of all to express my most sincere gratitude to Cardinal George Pell, to His Excellency Abp. Georg Gänswein, and to His Excellency Abp. Rino Fisichella for having accepted the invitation to present my book. In particular I thank you for your kind words of praise in my regard, and especially for what you said about my book, God or Nothing. Moreover I wish to thank those who promoted and organized this fine presentation ceremony: Dr. Paul Badde and Dr. Davide Cantagalli. Finally I wish to thank each one of you for your presence. His Excellency Abp. Georg Gänswein reminded us that today we celebrate the memory of Pope Saint Gelasius. This is a sheer coincidence, because today is my fifth anniversary as a cardinal.

How did the book God or Nothing come about?

To tell the truth, I had never thought of writing a book, until now. One day Dr. Nicolas Diat came to see me for an exchange of ideas about various questions and, at the end of a second meeting, proposed that I write a book about my life. I replied that it was not at all interesting, that there were so many lives finer and richer than mine, but—I added—by means of an interview we might possibly touch on some current ecclesial and social questions about our increasingly globalized and confused world. Even in the Catholic Church we no longer have a safe doctrinal and moral path. Everyone proclaims his own opinions and value with absolute freedom. I too would like to proclaim my faith and my fidelity to Jesus, to the centuries-old Magisterium of the Church. We began therefore with the first two chapters that relate my personal experience, lived out in a particularly difficult socio-political context—that of the revolution in Guinea with Sékou Touré, with extremely tense relations between the Church and the State of Guinea, difficulties and tensions that resulted in the expulsion of the first archbishop of Conakry, Msgr. Gérard de Milleville, the arrest and incarceration of the second archbishop of Conakry, Msgr. Raymond Marie Tchidimbo, the expulsion of all the missionaries in May of 1967, and 26 years of dictatorship and persecution. I, myself, in April 1984, was put on a list of persons to be eliminated, but was spared death thanks to Divine Providence. When I think back on my life, on my “nomadic” vocational journey—Guinea, Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea again, France, Senegal—I clearly discern in it concrete proof of divine predilection toward me.

After these first two chapters, there are some reflections on the popes, the Church, Rome, the modern world, Africa, the profound crises in anthropology and faith in the Western world, morality, truth, evil, prayer, etc. But God is truly the heart of God or Nothing. Why this title? Because today we observe an eclipse, an absence of God from the political, economic, and cultural world. The real crisis that our world is going through now is not essentially economic or political, but a “crisis of God.” Of course, people talk today only about the economic one: in the development of the economic power of Europe—although its original orientations were more ethical and religious—the economic interest has become more and more exclusively decisive. The man of yesterday, like today’s man, without distinction as to race, skin color, culture, country, or continent, is oriented almost exclusively toward the possession and use of material goods. And in the more specific cultural context of Western society, it is no exaggeration to say that man works, organizes, and manages human, political, economic, and commercial relations, starts wars, produces weapons of mass destruction, invades and conquers countries solely or almost exclusively to exploit and accumulate their material riches, in support of his own authority and hegemony. Under the pretext of bringing democracy, peace, and freedom, the West has created chaos in many countries, especially in the Middle East. My judgment may be inaccurate or exaggerated, but we cannot deny the present reality. Above all, Western culture has progressively organized itself as though God did not exist: many today have decided to do without God. As Nietzsche declares, for many in the West, God is dead. And we are the ones who killed Him, we are His assassins, and our Churches are the crypts and tombs of God. A lot of believers no longer attend them so as to avoid smelling the putrefaction of God; but in doing so, man no longer knows either who he is or where he is going: there is a sort of return to paganism and idolatry; science, technology, money, power, unbridled freedom, and endless pleasures are our gods.

I maintain that what we are experiencing today, especially but not only in the West, results from the fact that we have abandoned God in order to assign importance to “nothing.” Of course, the economy, politics, science, technology, and major advances in the fields of health care and social communications are not “nothing,” but in comparison to God they truly are “nothings.”

In God “we live and move and have our being” (Acts 17:28). In him, all things continue to exist. He is the Beginning, the seat of all Fullness, Saint Paul tells us; apart from him, nothing reigns: everything finds in God its own being and its own truth; otherwise it is “God or nothing.” Certainly, there are enormous problems, often painful situations—human life can be difficult and distressing; and yet we must recognize that God is the one who gives meaning to everything. Our worries, our problems, our sufferings exist and preoccupy us, but we know that everything is resolved in him, we know that it is God or nothing, and we perceive this as a self-evident truth that impresses us not from outside, but from within the soul, because Love is not imposed with violence, but by seducing the heart with an interior light.

With God or Nothing I would like to manage to put God back at the center of our thoughts, at the center of our action, at the center of our lives, in the one place that he should occupy, so that our journey as Christians might revolve around this Rock who is God, around this solid certitude of our faith.

Without praise, without prayer, without adoration and therefore without God, there is nothing but wars, division, and bewilderment. Without God in the heart of man, there is only hatred, strife, and conflicts, as we see today. I would like to illustrate this assertion of mine with this story taken from the hagiographic legend of the Muslim “saints.” We know from experience that having an unfriendly or bad neighbor can make life unpleasant. But this difficulty can last 20, or at most 50 years, and then death separates us. But living with a bad neighbor for eternity is much more unpleasant, and so it is better to know him first. Abdalwânid Ibn Zeid wanted to know who would be his neighbor in paradise. He was told: “O Abdalwânid Ibn Zeid, you will have as your neighbor Maïmouna la Nera.” “And where is this Maïmouna?” he asked. “She is from Banou un-Tel, in Koûfa.” Abdalwânid Ibn Zeid arrived in Koûfa and inquired about Maïmouna. They answered that she was a madwoman who pastured her sheep near the cemetery. Abdalwânid Ibn Zeid went to the cemetery and found Maïmouna in prayer. Maïmouna’s sheep were grazing by themselves, but what was even more astonishing and marvelous was that the sheep were mingled with wolves, and the wolves were not devouring the sheep and the sheep were not afraid of the wolves. When Maïmouna had finished praying, Abdalwânid Ibn Zeid asked Maïmouna: “How is it possible that the wolves get along so well with the sheep?” And Maïmouna replied: “I improved my relations with God and He improved the relations between my sheep and the wolves.”

Human efforts, political or diplomatic negotiations alone, will not succeed in attaining unity and reestablishing peace among men, because there is a virus of division, of disunity that is harbored in the hearts of men since original sin. The unity of the sons of God is a work that only Jesus can accomplish through the Holy Spirit, but without prayer the Spirit runs into a closed door in our souls. Let us therefore make more room for prayer and adoration in our lives, and then each one of us will be able to say: “I improved my relationship with God and He improved and pacified the relations among men and among peoples.”

December 8, 2015

Bestselling author provides invaluable guide toward embracing Divine Mercy

SAN FRANCISCO, Dec. 8, 2015 – The Jubilee Year of Mercy begins today on the feast of the Immaculate Conception and the 50th anniversary of the closing of the Second Vatican Council. Pope Francis has called us to “live lives shaped by mercy,” and benefit greatly from the Year of Mercy.

The ideal resource for the Year of Mercy is bestselling author Vinny Flynn’s soon-to-be-released book 7 SECRETS OF DIVINE MERCY, which draws from Scripture, the teachings of the Catholic Church and the Diary of St. Faustina — Flynn was one of the original editors of the official English edition of the diary — to reveal the heart of Divine Mercy. Flynn offers an inspirational road map to help us experience the overflow of transforming love from the Holy Spirit during the Year of Mercy.

which draws from Scripture, the teachings of the Catholic Church and the Diary of St. Faustina — Flynn was one of the original editors of the official English edition of the diary — to reveal the heart of Divine Mercy. Flynn offers an inspirational road map to help us experience the overflow of transforming love from the Holy Spirit during the Year of Mercy.

“It is absolutely essential for the Church and for the credibility of her message that she herself live and testify to mercy,” said Pope Francis. Mercy, he says, is “the beating heart of the Gospel” To live mercy, we must rediscover both the spiritual works of mercy (counsel the doubtful, instruct the ignorant, admonish sinners, comfort the afflicted, forgive offenses, bear patiently those who do us ill and pray for the living and the dead) and the corporal works of mercy (feed the hungry, give drink to the thirsty, clothe the naked, welcome the stranger, heal the sick, visit the imprisoned and bury the dead).

Divine Mercy is the key devotion, the umbrella devotion over everything else. Every other devotion in the Church, every ritual, every activity, every teaching, is under that umbrella of Divine Mercy. As Flynn shows us in 7 SECRETS OF DIVINE MERCY, everything in our lives can become more meaningful, more powerful and more life-changing once we really embrace the gift of Divine Mercy — the overflow of love from the Holy Trinity.

For more information, to request a review copy or to schedule an interview with Vinny Flynn, please contact Kevin Wandra (404-788-1276 or KWandra@CarmelCommunications.com) of Carmel Communications.

The empiricists and their rubes

(us.fotolia.com | aihumnoi)

The empiricists and their rubes | Thomas M. Doran | The Dispatch at Catholic World Report

Or why atheists don’t have a corner on reason

Catholic World Report recently published my mischievously titled “Why we’d all be Catholic if we really thought about it”, to which no small number of atheistic empiricists replied with loud roars.

There’s no lack today of atheistic empiricists who loudly and insistently proclaim that they’re the only ones who know how to think and reason, and that religiously inclined people can’t, or don’t. When I speak of empiricists, I’m talking about people with a materialistic view of the world and life, where only what we can measure is real, often combined with anti-religion. They are proud and evangelizing atheists. And many of them are productive members of society, colleagues, family members, and friends. So long as the conversation doesn't descend to name-calling or bluster, I enjoy talking to them, debating them, listening to their perspective. And yes, I myself have to be vigilant against bluster.

First, a few of the atheistic empiricists’ blind spots. Others have ably demonstrated that atheism—the assertion that God doesn’t exist—is irrational. To deny (as compared to agnostic questioning) the existence of God requires conclusive proof that God doesn’t exist. As the universe is a pretty big place and as there are more than a few things we don’t know about it and as many of the things we once thought we knew are now known to be other than what we once thought, making the bold statement that there is no God is irrational, according to the definition of the word. Think of how hard it would be to conclusively prove there are no 6-toed purple, yellow, and red frogs on Earth, just one planet in one galaxy. In what little nook or cranny might such a frog exist, even if just one mutation?

Second, many atheistic empiricists accept on “faith”, i.e., the witness of people they deem credible, scientific principles such as black holes and related theories about the retention of fundamental particle information in black holes or at their event horizons, dark matter, string theory, that they themselves don’t understand, meaning they can’t follow the advanced mathematical proofs themselves. Thus, these beliefs become a matter of trusted testimony rather than evidence.

December 5, 2015

Living Between the First and Final Coming of Christ

Icon of Second Coming, c. 1700 [commons.wikimedia.org]

A Scriptural Reflection on the Readings for Sunday, December 6, 2015, Second Sunday of Advent | Carl E. Olson

Readings:

• Bar 5:1-9

• Ps 126:1-2, 2-3, 4-5, 6

• Phil 1:4-6, 8-11

• Lk 3:1-6

"There are three distinct comings of the Lord of which I know," wrote St. Bernard of Clairvaux, the great twelfth-century doctor of the Church, in one of his Advent sermons, "his coming to people, his coming into people, and his coming against people."

He added that Christ's "coming to people and his coming against people are too well known to need elucidation." Since, however, today's Gospel reading mentions both groups—those Christ comes to and those he comes against—a bit of elucidation is in order.

St. Luke took pains to situate the fact of the Incarnation within human history. He did so by providing the names of several different rulers, beginning with Caesar Augustus (Lk. 2:1), who reigned from 27 B.C. to A.D. 14, and who was ruler of the Roman Empire when Jesus was born. In today's Gospel, the Evangelist situates John the Baptist's bold announcement of Christ's coming in the fifteenth year of Tiberius Caesar. Tiberius, the stepson of Augustus, reigned from A.D. 14 to 37. Pontius Pilate was appointed procurator of Judea by Tiberius in 26, and served in that post for ten years. Those men and the others mentioned by St. Luke—Herod, Philip, Lysanias, and the high priests Annas and Caiaphas—ruled the known world while the ruler of all creation walked the dusty roads of Palestine and announced the kingdom of God was at hand.

The Roman rulers were ruthless and often violent men who established rule and kept order through military might and political power. They did, in fact, establish and keep a sort of peace—the pax Romana—which lasted about two centuries (27 B.C. - c. A.D. 180). Yet that peace was both uneasy and fragile; it had been won by the sword and often relied on fear, intimidation, and persecution. St. Luke's mention of these rulers was, on one hand, meant to support the historical nature of his "orderly account," which was to be "a narrative of the things which have been accomplished among us..." (see Lk. 1:1-4).

But it was also meant to establish a deliberate comparison and contrast between the rulers of this world and the ruler of nations, between the kings of earthly realms and the King of kings. The Roman rulers used force and relied upon fear, but the Incarnate Word came with humility and love. Emperors were announced and escorted by armed soldiers, but the birth of the Christ child was announced by heavenly hosts offering songs of praise, not swords or spears. "What the angel proposes to the shepherds is another kyrios [Lord]," wrote Fr. Robert Barron in The Priority of Christ (Brazos, 2007), "the Messiah Jesus, whose rule will constitute a true justice because it is conditioned not by fear but by love and forgiveness..."

The Lord came against injustice, fear, violence, and death, and would himself experience each of those dreadful realities for the sake of all men. Such would be "the salvation of God" spoken of John the Baptist, who quoted from Isaiah's beautiful and moving hymn-like reflection on the glory and goodness of God (Isa. 40). John, like Isaiah, was pointing toward the comfort, peace, and joy that only God can give.

Yet the final rest and joy is not yet fully known. We live, St. Bernard explained, during the time of the "third coming" of Christ, between the Incarnation and the final coming, or advent, when all men will finally see the pierced but glorious Lord. "The intermediate coming is a hidden one; in it only the elect see the Lord within their own selves, and they are saved." Christ comes to us in spirit and in power; he most especially comes to us under the appearance of bread and wine.

"Because this coming lies between the other two," wrote St. Bernard, "it is like a road on which we travel from the first coming to the last." That winding road is the way of the Lord, the path of Advent.

(This "Opening the Word" column originally appeared in the December 6, 2009, edition of Our Sunday Visitor newspaper.)

The Unbearable Oppression of Yoga

(us.fotolia.com | DragonImages)

The Unbearable Oppression of Yoga | Dr. Christopher S. Morrissey | CWR

What to make of the current craze of student activists who seek explicit institutional enforcement of “safe spaces” on campus?

Traditional logic is famous for classifying human beings as “rational animals.” What would traditional logicians make of the current craze of student activists who seek explicit institutional enforcement of “safe spaces” on campus?

Student protests have erupted in recent weeks, most notably at Yale University and the University of Missouri. As fascinating demands are made, much tumult has ensued. The president of the University of Missouri has even resigned.

The wave of activism has spread to many campuses besides Yale and Mizzou. Student temperament is perhaps best illustrated by the first demand made by the uprising at Amherst College:

President Martin must issue a statement of apology to students, alumni and former students, faculty, administration and staff who have been victims of several injustices including but not limited to our institutional legacy of white supremacy, colonialism, anti-black racism, anti-Latinx racism, anti-Native American racism, anti-Native/ indigenous racism, anti-Asian racism, anti-Middle Eastern racism, heterosexism, cis-sexism, xenophobia, anti-Semitism, ableism, mental health stigma, and classism. Also include that marginalized communities and their allies should feel safe at Amherst College.

If you are wondering where this sort of thing will wind up, perhaps the student leaders at the University of Ottawa, who recently voted to shut down a yoga class, have given us a glimpse of the politically correct reductio ad absurdum. Since Canadians like to congratulate themselves on being more forward thinking and liberally enlightened than their southern neighbors, it might be the shape of progressive things to come in America.

The Ottawa yoga class was to be offered to about 60 students through the university’s Centre for Students with Disabilities. Although apparently no one had complained, the university’s Student Federation president Romeo Ahimakin said the yoga program was suspended in order that students could be consulted about how “to make it better, more accessible and more inclusive to certain groups of people that feel left out in yoga-like spaces.”

Yoga instructor Jennifer Scharf had been offering the course since 2008 through the Centre. On its website, the Centre for Students with Disabilities describes its commitment to “challenge all forms of oppression”, and professes that while “working to dismantle ableism, we also work to challenge all forms of oppression including, but not limited to, heterosexism, cissexism, homophobia, transphobia, biphobia, queerphobia, HIV-phobia, sex negativity, fatphobia, femme-phobia, misogyny, transmisogyny, racism, classism, ableism, xenophobia, sexism, and linguistic discrimination.”

In an email, explaining their new challenge aimed at yoga’s oppressiveness, staff at the Centre said that “while yoga is a really great idea and accessible and great for students ... there are cultural issues of implication involved in the practice... Yoga has been under a lot of controversy lately due to how it is being practiced”; that is, the practice of yoga is apparently an oppressive form of cultural appropriation, since yoga comes from cultures that “have experienced oppression, cultural genocide and diasporas due to colonialism and western supremacy ... we need to be mindful of this and how we express ourselves while practising yoga.”

However, the yoga instructor, who was rebuffed when she had offered to change the name of the class (from “yoga” to something perhaps more palatable to political correctness: “mindful stretching”), summed up her view of the situation by commenting, “People are just looking for a reason to be offended by anything they can find.”

What I find most interesting about this risible episode is the fact that rational animals are the only animals that go looking for reasons. What then has happened with student rationality, bringing it to where it is in this yoga case?

Homilies for December 2015: Second Sunday of Advent, December 6th

by Fr. Thomas McQuillen | Homiletic & Pastoral Review

Adoration of the Shepherds by Francois Boucher, ca. 1761-62.

Second Sunday of Advent—December 6, 2015

Readings: http://usccb.org/bible/readings/120615.cfm

Experiencing New Life through Christ’s Coming this Christmas

This coming week, Pope Francis will open the holy door at St. Peter’s basilica and start the Extra-ordinary Jubilee of Mercy. And thus in this extra opened door of the church will be symbolized the hope of the Church. The hope that more people will be able to enter and receive the mercy of God. The hope that more people will be able to come and behold the face of God.

As the Pope states: “Jesus Christ is the face of the Father’s mercy.” (Misericordiae Vultus, 1) But this season of Advent recalls the events leading up to the birth of Christ, to Christmas. They recall the events before the face of Christ was revealed, and to help us understand the meaning of these events, let us start by recalling the meaning of being born.

Many years ago, before the advent of ultrasound, I had a conversation with a friend who was in her eighth month of pregnancy. As we met, I asked her how she was doing.

She began to talk about how wonderful she felt. This was her second child and she never felt better—there was no morning sickness or drowsiness, indeed her faced radiated. She said that she loved being pregnant, she loved how she felt physically, and she loved the mystery and wonder of it. And here the conversation began to shift.

She then started to talk about the child and related how she and her husband, would marvel about this new life about to come into their lives. Here was a new life, a new member of their family, already so much a part of their lives, already greatly loved, yet they knew so little about this person.

December 2, 2015

Why the Unreality?

(us.fotolia.com | yanlev)

Why the Unreality? | James Kalb | CWR

Making sense of the position and power that secular progressivism holds in public life today requires understanding both its theoretical side and its institutional side

People who reject secular progressivism, especially in its more highly developed forms, are often puzzled by its proponents. Do they really believe what they say they believe, for example that diversity is always strength, or traditional religion and morality are dangerous and irrational bigotries, or there are no significant differences between men and women?

Some say they don’t really believe such things, at least the informed and intelligent ones don’t, but just find them politically useful as claims. That view would make secular progressivism a matter of cynical demagogy and power seeking.

Others say they believe what they say they believe, but do so because of psychological quirks or historical particularities. Leftists are perpetual adolescents always in rebellion, or they’re so horrified by slavery, segregation, colonialism, Nazism, or the Wars of Religion that they find anything other than compulsory equality and rejection of transcendent claims intolerably dangerous.

Such views don’t explain the position secular progressivism holds in public life today: its increasing grip on institutions and professions, its extension to ever more aspects of life, its success in remaking mainstream political and religious movements in its image, its ambition to silence all opposition, its resilience that enables it to come back from all reverses. When non-progressives say some new initiative is silly and won’t last—“gay marriage,” “micro-aggressions,” or whatever—they’re routinely proven wrong, at least on the second point.

Such successes argue for an outlook that is rooted in basic and enduring features of modern life and how modern people look at the world. They show that even what seem like absurdities can’t be laughed off, but must be taken very seriously, because there’s more thought and institutional momentum behind them than might appear.

What I’m calling progressivism, which is the dominant view of our time, has a theoretical and an institutional side. On the theoretical side it might be summed up as a tendency toward scientism, the view that an idealized version of modern natural science is the unique model for knowledge and reason. That view denies qualitative distinctions and turns goods into preferences, because it wants to accept only what is publicly observable and quantifiable. It also implies a sort of moral egalitarianism: preferences define what is good, and all preferences are equally preferences, so they are equally valid and have an equal claim to satisfaction. To reject a preference is baseless discrimination against the person whose preference it is, and thus a form of hatred and oppression.

It’s worth noting that scientism is not scientific, and often aligns itself with obfuscation.

November 28, 2015

Advent orients us to the heart of the Nativity

"La Nativite a la Torche" ("Nativity with the Torch") (17th century) by Le Nain brothers [WikiArt.org]

A Scriptural Reflection on the Readings for November 29, 2015, the First Sunday of Advent | Carl E. Olson

Readings:

• Jer 33:14-16

• Ps 25:4-5, 8-9, 10, 14

• 1 Thes 3:12-4:2

• Lk 21:25-28, 34-36

“We preach not one advent only of Christ,” wrote St. Cyril of Jerusalem in the fourth century, “but a second also, far more glorious than the former. For the former gave a view of His patience; but the latter brings with it the crown of a divine kingdom.”

The term “advent,” as we’ll see, is drawn from the New Testament, but when St. Cyril (named a Doctor of the Church in 1883 by Pope Leo XIII) was writing his famous catechetical lectures, the season of Advent was just starting to emerge in fledgling form in Spain and Gaul. During the fifth century, Christians in parts of western Europe began observing a period of ascetical practices leading up to the feasts of Christmas and Epiphany. Advent was observed in Rome beginning in the sixth century, and it was sometimes called the “pre-Christian Lent,” a time of fasting, more frequent prayer, and additional liturgies.

One of the prayers of the Roman missal from those early centuries says, “Stir up our hearts, O Lord, to prepare the ways of Thy only-begotten Son: that by His coming we may be able to serve him with purified minds.” This echoes today’s reading from St. Paul’s first letter to the Christians in Thessalonica, in which he exhorts them “to strengthen your hearts, to be blameless before our God and Father at the coming of our Lord Jesus with all his holy ones. Amen.”

The Greek word used by St. Paul for “coming” is parousia, which means “presence” or “coming to a place.” The Vulgate translation of the phrase “the coming of our Lord Jesus” (1 Thess 3:13) is rendered “in adventu Domini.” The word parousia appears twenty-four times in the New Testament, almost always in reference to the coming or presence of the Lord. It appears in Matthew 24 four times, the only place the term appears in the Gospels; that chapter records the Olivet Discourse, Jesus’ prophetic warnings about a coming time of trial, destruction, and “the coming of the Son of man” (Matt 24:27). Today’s Gospel reading, from Luke 21, is a parallel passage warning of distress, startling heavenly signs, and “the Son of Man coming in a cloud with power and great glory.”

What connection is there between the foment of earthly tribulation and cosmic upheaval, and preparations to celebrate Christ’s birth? If we consider the Christmas story cleared of sentimental wrappings, we see events as dramatic, raw, bloody, and joyous as can be imagined: the birth of Christ, the slaughter of the innocents, the praise of angels, the murderous rage of Herod. Christmas is about birth, but also death; about rejoicing, but also rejection. It is the story of God desired and God denied. It is the story every man has to encounter because it is the story of God’s radical plan of salvation, the entrance of divinity into the dusty ruts and twisting corridors of human history.

Advent orients us to the heart of the Nativity—not in a merely metaphorical way, but through the reality of the liturgy, the Eucharist, the sacramental life of the Church. It is a wake-up call, perhaps even an alarm rousing us from “carousing and drunkenness and the anxieties of daily life.” The birth of Christ caught many by surprise. Likewise, we can find ourselves trapped in the darkness of dull living and missing Christ’s call to raise our heads as salvation approaches.

“Advent calls believers to become aware of this truth and to act accordingly,” said Pope Benedict XVI in a homily marking the beginning of Advent in 2006. “It rings out as a salutary appeal in the days, weeks and months that repeat: Awaken! Remember that God comes! Not yesterday, not tomorrow, but today, now!” Jesus told his disciples to be vigilant, prepared, and prayerful.

The same is true for his disciples today, so they might escape the tribulations of spiritual darkness and stand purified and prepared before the Son of Man, the son of Mary.

(This "Opening the Word" column appeared originally in the November 29, 2009, issue of Our Sunday Visitor newspaper.)

November 27, 2015

Sacred Liturgy: Great Mystery, Great Mercy

The Ghent Altarpiece “Adoration of the Lamb”, by Jan Van Eyck.

Sacred Liturgy: Great Mystery, Great Mercy | Bishop Peter J. Elliott | Homiletic & Pastoral Review

Archbishop Peter Richard Kenrick Lecture, Kenrick Glennon Seminary, St Louis, MO, October 8, 2015

Reflecting on the state of divine worship in the Church, I believe that this is a good time for Catholics of the Roman Rite, a very good time. Fifty years after the Second Vatican Council initiated a liturgical reform in the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy, Sacrosanctum Concilium, we now inherit the eucharistic project of the last years of Saint John Paul II, and the liturgical project and “pax liturgica” of Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI. Pope Francis respects this inheritance. His liturgical style may be simpler than his predecessor, but he has maintained what he achieved. Benedict and Francis both revere the German scholar Romano Guardini, a deep influence on sound liturgical renewal.1

CATHOLIC WORSHIP TODAY

The papal projects are gradually correcting a misapplication of the post-Conciliar liturgical reform, discontinuity, or rupture from our tradition, with many errors and abuses. However, in surveying where we are, I do not wish to dwell on poor liturgy. I emphasize examples of how the situation is improving, leading into my major themes, mystery and mercy.

Liturgy, Made or Given

One major misinterpretation of Sacrosanctum Concilium is that we make the liturgy, that worship is something we fabricate or put together, not a gift of the Church handed on to us within a living tradition. To all of us is entrusted this gift of liturgical worship, with its own patterns, plan, laws, logic, and cultural qualities.

In this context, myths linger such as the “gathering rite,” implying that we gather ourselves for worship. Pope Benedict insisted that God gathers us for worship, just as he called his Chosen People out of Egypt, to assemble in the wilderness, there to learn how to worship, through sacrifice to the true God, and how to live justly, following the Commandments of God’s Law.2 In the Third Eucharistic Prayer, we address God the Father: “You never cease to gather a people to yourself,” a people later described as “this family, whom you have summoned before you.”

Didacticism

In not a few parishes, the liturgical reform drifted away from worship, to teaching and edifying instruction, to didacticism. The church became an auditorium for imparting messages—and doing what you are told. This was underlined by an irritating commentator, a histrionic cantor (she of the upraised arm and the glinting eyes) and, especially, when the celebrant acted like a television compere, or an earnest coach giving his team a pep talk. This liturgical decadence is fading, even if not everywhere.

Carl E. Olson's Blog

- Carl E. Olson's profile

- 20 followers