Carl E. Olson's Blog, page 28

November 15, 2015

The Son of Man and the Little Apocalypse

"Destruction of the Temple of Jerusalem" (1867) by Francesco Hayez [WikiArt.org]

A Scriptural Reflection on the Readings for Sunday, November 15, 2015 | Carl E. Olson

Readings:

• Dn 12:1-3

• Ps 16:5, 8, 9-10, 11

• Heb 10:11-14, 18

• Mk 13:24-32

At the start of this month, On the Solemnity of All Saints, the first reading was from The Apocalypse, the Book of Revelation. It described the saints from the perspective of heaven, showing them to be marked and sealed by God, set apart as holy. Next Sunday, on the Solemnity of Christ the King, the epistle reading is from the opening chapter of the same book. It describes Jesus Christ as the ruler of kings of the earth who “is coming amid the clouds” to judge all men at the end of time.

Today’s reading from the Gospel of Mark is closely related. It is from the Olivet Discourse, sometimes called a “little apocalypse” (see Mt 24-25 and Lk 21) because it contains difficult teachings by Jesus about the destruction of the Jerusalem temple in A.D. 70 and the final day of judgment. Like The Apocalypse of John the Revelator, the little apocalypse is filled with strong imagery and a complex web of allusions drawn from the Old Testament, especially from the prophets.

The challenge of making sense of today’s Gospel reading (and many related passages) is highlighted in Jesus, The Tribulation, and the End of the Exile (Baker Academic, 2005), written by Dr. Brant Pitre, a Scripture scholar who teaches at Our Lady of Holy Cross College in New Orleans. Pitre’s impressive study draws together a host of interwoven themes rooted in the Old Testament and referred by Jesus in his discourse, including the exile, the tribulation, the elect, the temple, and the messiah. I’ve chosen three insights provided by Pitre that will, hopefully, help readers better understand today’s Gospel reading.

The first is that the images of darkened sun and moon, falling stars, and the shaken powers of heaven were frequently used by Isaiah, Jeremiah, Joel, Amos, and other prophets. They referred to one or several of the following: a day of divine judgment, the destruction of a foreign city (Babylon, for example), the destruction of Jerusalem (Isa 24:10-23; Jer 4:11-31), the restoration of Israel from exile, and the coming of the Messiah (Isa 13:10-14:2). Put simply, Jesus was not employing heavily coded language, but the heavenly language of the prophets. “A close study of the similar images of heavenly tumult,” writes Pitre, “shows that Jesus’ forecast stands directly in line with the oracles of the ancient Israelite prophets and early Jewish eschatological writings.”

Secondly, Jesus used this language to describe his approach Passion and death, through which he, the promised Messiah, would deliver his people from tribulation and inaugurate the restoration of Israel. The prophecies of Daniel are essential, for they speak of “the son of man coming in the clouds” (Dan 7:13), a figure Jesus clearly identifies with himself (Mk 13:26; 8:38). The Son of Man will “gather his elect” and lead a new exodus out of sin and death and form the new Israel, the Church, through the new covenant of his blood.

Finally, the destruction of Jerusalem and the temple are central events, both historically and theologically, in this epic plan of salvation. Recall that Jesus, in considering the spiritual state of Jerusalem, said, “Behold, your house is forsaken and desolate” (Mt 23:38). This desolation, Pitre argues, refers to the cessation of sacrifice, which is the “abomination of desolation” referred to by Daniel (Dan 9:27; 11:31; 12:11). The sacrifices of the temple, having ended in sacrilege, were fulfilled and replaced by the perfect sacrifice of the Lamb of God, which takes away the sins of the world.

“Just as the first Exodus had been preceded and set in motion by a paschal sacrifice during a time of great trials and plagues,” Pitre explains, “so too Jesus saw his death as setting in motion the great paschal and eschatological trial that would bring about the restoration of Israel.” Today’s reading from Hebrews indicates this trial and restoration is still ongoing, as Jesus “waits until his enemies are made his footstool.” Meanwhile, we worship and serve a risen Lord and look to the return of the Son of Man.

(This "Opening the Word" column originally appeared in the November 15, 2009, edition of Our Sunday Visitor newspaper.)

November 12, 2015

Vatican II and Religious Freedom: Rupture or Authentic Development?

People hold candles in the form of a cross during avigil in St. Peter's Square at the Vatican Oct. 11, 2012, to mark the 50th anniversary of the opening of the Second Vatican Council. (CNS photo/Giancarlo Giuliani, Catholic Press Photo)

Vatican II and Religious Freedom: Rupture or Authentic Development?

The authors of a new book on “Dignitatis Humanae” argue one of Declaration's great achievements is to develop an understanding of human dignity and human freedom grounded in the human person's constitutive relation to God

One of the most contentious and heavily debated topics in the Church during and following the Second Vatican Council is that of religious freedom. In recent years, questions about the nature, parameters, and recognition of religious liberty have become even more timely and pressing in the United States and other Western nations. In Freedom, Truth, and Human Dignity (Eerdmans, 2015), Dr. David L. Schindler and Dr. Nicholas J. Healy offer a rigorous and detailed examination of Dignitatis Humanae, the Council's “Declaration on Religious Freedom”, providing a new translation, a redaction history, and a rich and provocative interpretation of the text.

Dr. Schindler, who is the Edouard Cardinal Gagnon Professor of Fundamental Theology at the Pontifical John Paul II Institute for Studies on Marriage and Family at The Catholic University of America, Washington DC, and Dr. Healy, assistant professor of philosophy at the Pontifical John Paul II Institute for Studies on Marriage and Family at The Catholic University of America, recently responded to written questions from Carl E. Olson, editor of Catholic World Report, about their book, Dignitatis Humanae,

CWR: In the Preface to Freedom, Truth, and Human Dignity, you state that the book "seeks to promote a deeper understanding of the Second Vatican Council's Declaration on Religious Freedom." What are some specific reasons that such an understanding is important fifty years after the Council?

Dr. Healy: The Declaration on Religious Freedom, Dignitatis Humanae, was the most controversial document of the Second Vatican Council. A significant minority of Council fathers harbored reservations on the grounds that the Declaration seemed to depart from established Catholic doctrine on the duties of the state toward the Catholic religion. Within the majority that supported an affirmation of religious freedom, there were deep disagreements about the nature and foundation of the right to religious freedom and the relationship between freedom and truth. Although approved by an overwhelming majority of Council fathers and commended by Pope Paul VI as "one of the greatest documents" of the Council, Dignitatis Humanae has remained a source of controversy and debate. Behind Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre's schismatic act of consecrating bishops without papal mandate was a conviction that the Declaration represented a departure from Catholic doctrine and a capitulation to the heresy of modernism. Among the supporters of religious freedom, the disagreements that accompanied the drafting of the Declaration have served as a fault line for differing accounts of the nature and ground of religious freedom, and the significance of this teaching for the relationship between the Church and modernity.

One reason why the Declaration continues to generate interest and debate is the central importance of the question of freedom for the Church's encounter with contemporary culture. “The era we call modern times,” Joseph Ratzinger observed, “has been determined from the beginning by the theme of freedom; the striving for new forms of freedom.” Both Gaudium et spes and Dignitatis Humanae acknowledge the legitimacy of this aspiration for freedom. At the same time, the Council fathers recognized the need for a critical discernment of the modern idea of freedom in light of the truth of human nature and the Christian mystery of redemption in Christ.

Freedom is not simply the capacity to choose between alternatives; it is a sign of the ontological dignity of the human person who is created in love and called to live in communion with the truth. One of the great achievements of the Declaration is to develop an understanding of human dignity and human freedom that is grounded in the human person's constitutive relation to God. In the words of John Paul II, "the freedom of the individual finds its basis in man's transcendent dignity: a dignity given to him by God the Creator and Father, in whose image and likeness he was created." There is no freedom without truth, and no truth without freedom.

In the face of new challenges and new threats to religious freedom, it is important to rediscover the Council's authentic teaching on the right to religious freedom as grounded in the obligation to seek the truth about God. As Gaudium et spes teaches, once God is forgotten, the creature is lost sight of as well. Especially in our time, it is necessary to uphold the transcendent and relational dignity of the human person, who is created by God and destined to share in the "glorious freedom of the children of God" (Rom 8:21).

CWR: What are some of the resources that your book provides to help readers understand and interpret Dignitatis Humanae?

November 11, 2015

Now available: A new edition of "Wisdom and Innocence: A Life of G.K. Chesterton" by Joseph Pearce

New from Ignatius Press:

Wisdom and Innocence: A Life of G.K. Chesterton

by Joseph Pearce

Paperback, 544 pages

Through years of meticulous research and access to the literary estate of G.K. Chesterton, Joseph Pearce presents a major biography of a 20th century literary giant, providing a great deal of important information on GKC never before published.

This is a thoroughly readable and delightful biography of a multi-faceted author, artist and debater who loved the friendship of children, idolized his wife and enjoyed great friendships with the likes of Hillaire Belloc, Bernard Shaw and H.G. Wells. Illustrated.

Joseph Pearce is the author of numerous literary works including Literary Converts, The Quest for Shakespeare and Shakespeare on Love, and the editor of the Ignatius Critical Editions series. His other books include literary biographies of Oscar Wilde, J.R.R. Tolkien, C. S. Lewis, G. K. Chesterton and Alexander Solzhenitsyn.

"An astonishing biography of an astonishing man. Pearce has done his research thoroughly and well, bringing to the reading public a superb biography containing information and material heretofore unknown about one of the truly influential men of his time—G. K. Chesterton."

— Midwest Book Review

"Pearce celebrates Chesterton’s happy family life, successful marriage, and friendships with Belloc, Shaw, and other Victorian and twentieth-century writers. Also detailed are Chesterton’s social and political activism, as well as his romanticism and childlike joie de vivre ."

— Library Journal

"This book is a fresh reminder of how good Chesterton could be."

— The Sunday Telegraph

November 10, 2015

New Belgium Archbishop: Mercy is "somewhat condescending...I like words like 'respect' and 'esteem'"

(Photo: us.fotolia.cop | siraanamwong)

New Belgium Archbishop: Mercy is "somewhat condescending...I like words like 'respect' and 'esteem'" | Carl E. Olson | The Dispatch at CWR

Archbishop-elect Jozef De Kesel also indicates his hope that the Church will soon allow "divorced and remarried Catholics to receive Communion."

If an archbishop-elect thinks the word "mercy" is "somewhat condescending", what must he think of words such as "sin", "damnation", "hell", and "orthodoxy"? Alas, we don't know for certain, but perhaps that just as well, if only for the sake of keeping one's stomach under control. The prelate in question is Jozef De Kesel of Mechelen-Brussels, interviewed by Kerknet and translated into English by Mark de Vries of "In Caelo et in Terra", who covers Catholic news in the Netherlands. The fuller quote:

You did not take part in the Synod on the family, but will probably get to work with its proposals. What will stay with you from this Synod?

“The Synod may not have brought the concrete results that were hoped for, such as allowing divorced and remarried Catholics to receive Communion. But it is unbelievable how much it was a sign of a Church that has changed. The mentality is really not the same anymore.

I may be a careful person, but I do not think we should be marking time. Mercy is an important word for me, but in one way or another it is still somewhat condescending. I like to take words like respect and esteem for man as my starting point. And that may be a value that we, as Christians, share with prevailing culture.”

Yes, the phrase "Belgium waffles" did come to mind—and heavy with syrup, please!—while reading this over breakfast. Not that a sensitive stomach can handle too much of this nonsense first thing in the morning. Alas, this sort of thinking—or feeling, which is more apt—is quite prevalent. I recently had a Catholic tell me that he thought the word "sin" was too harsh to use in speaking to his secular friends; he preferred the term "reconciliation". Again, the intent is to be "relevant", and the working assumption, apparently is that people today are so complicated and fragile, that the wrong word is going to trigger some sort of spiritual combustion.

But isn't that the point?

November 9, 2015

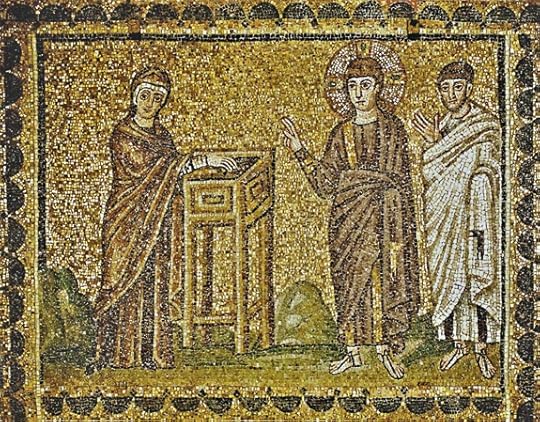

Widows and Scribes, Substance and Style

"The Widow’s Mite" (6th century) by Unknown Artist, in the Basilica di Sant’Apollinare Nuovo

Widows and Scribes, Substance and Style | A Scriptural Reflection on the Readings for Sunday, November 8, 2015 | Carl E. Olson

Readings:

• 1 Kngs 17:10-16

• Ps 146:7, 8-9, 9-10

• Heb 9:24-28

• Mk 12:38-44

“Substance over style.” This phrase is a good reminder that a culture filled with empty rhetoric, flashing lights, endless entertainment, and the promise of bigger and better cannot satisfy our ultimate needs and desires.

It also raises the question: What substance? How to identify it? Today’s guide to the answer is the widow.

Widows are mentioned close to a hundred times in the Bible. They have a special place, along with orphans, the fatherless, and the oppressed, within the Law and the Prophets; they represent those who are afflicted, vulnerable, and deserted. “You shall not afflict any widow or orphan,” the Lord told the Israelites, “If you do afflict them, and they cry out to me, I will surely hear their cry…” (Ex. 22:22-3). They were reminded that Yahweh is “the great, the mighty, and the terrible God, who is not partial and takes no bribe. He executes justice for the fatherless and the widow, and loves the sojourner, giving him food and clothing” (Deut. 10:17-18).

The widow met by the prophet Elijah was not only destitute, she was not an Israelite; Zarephath was a Phoenician town on the Mediterranean coast. Seeking shelter and safety from King Ahab, Elijah had been told by the Lord that the widow would be waiting for him (1 Kgs. 17:9). Both of them were in desperate straits, abandoned and isolated from any sort of earthly support. She, in fact, was resigned to death by starvation. But she did as the prophet of God directed her. Even in the face of death, she was willing to listen to voice of God, and so she and her son were blessed with a miraculous source of flour and oil.

The scribes were experts in the Law whose theological judgments carried great influence and authority. Jesus did not condemn them en masse, for in the passage prior to today’s Gospel reading he told a scribe, “You are not far from the kingdom of God” (Mk. 12:34). Yet he strongly criticized the conduct of many scribes, those who chose style over substance. They were more concerned with looking good, getting attention, and receiving honors than they were with the things of God and the plight of widows.

Some of them “devoured the houses of widows,” likely a reference to financial fleecing. Reliant on private donations, some scribes would say prayers meant for human ears and not for God. Rather than pleading for the widows (cf. Isa. 1:17), these scribes were taking advantage of them, something condemned strongly by the Law and the prophets.

This sinful behavior, an injustice to the widows and a denial of God’s commandments, is contrasted with the humility and trust of the poor widow, who came to the Temple and “put in two small coins worth a few cents.” Those coins were the smallest units of monetary currency, each worth about 1/64 of a laborer’s daily wage. The monetary value was small, but it was all that the widow possessed. She gave everything, “from her poverty … her whole livelihood.”

The widow’s physical poverty was real, and she had little or no control over it. But her spiritual poverty—that is, her humility and devotion to God—was also real, and it was the result of her will and her choosing. She embodied the first of the Beatitudes: “Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven” (Matt. 5:3).

“She had given not out of her surplus, but out of her substance,” notes Dr. Mary Healy in her commentary on The Gospel of Mark (Catholic Commentary on Sacred Scripture, Baker, 2008), “Her gift meant that she would have to rely on God even to provide her next meal. Such reckless generosity parallels the self-emptying generosity of God himself, who did not hold back from us even his beloved Son (Mk. 12:6).”

This sort of sacrificial giving and living is not, of course, much in style. But serving God is not about style. It is about substance.

(This "Opening the Word" column originally appeared in the November 8, 2009, edition of Our Sunday Visitor newspaper.)

November 5, 2015

René Girard's Genius and Generosity

René Girard in 2012 (YouTube)

René Girard's Genius and Generosity | Gil Bailie | CWR

A longtime friend and student of the renowned critic and philosopher recalls how Girard emphasized the necessity of aspiring to personal sanctity

Editor's note: René Girard, the influential literary critic and Catholic philosopher, died on November 4 at the age of 91 after a long illness. Born on Christmas Day, 1923 in Avingnon, Girard studied medieval history at the École des Chartes, Paris, and then came to the United States in 1947. After earning his doctorate at Indiana University, he held acadmic posts at Duke University, Bryn Mawr College, Johns Hopkins University, and the State University of New York in Buffalo. In 1981 he became the Andrew B. Hammond Professor of French Language, Literature, and Civilization at Stanford University, and he remained at Stanford until retiring in 1995. He was the author of over two dozen books, most notably Violence and the Sacred (1977) and Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World (1987). He was elected to the prestigious Académie française in 2005, and was awarded the Order of Isabella the Catholic, Commander by Number, by the Spanish head of state, H.M. King Juan Carlos, in 2013.

The following tribute is adapted in part from the forthcoming book Raising the Ante: God’s Gamble by Gil Bailie, a long-time friend and student of René Girard.

----------------

Girard’s Intellectual Genius

Until his retirement in 1997, René Girard held the Andrew B. Hammond Chair of French Language, Literature and Civilization at Stanford University. In 2005 he was elected to the French Academy. His work in the fields of literature, the humanities, and social science led him to recognize some quite obvious but rarely thematized anthropological facts: namely that, above and beyond instinctual appetite, there is a form of desire that profoundly shapes and fairly defines human motivation, namely mimetic desire, desire aroused by another’s desire and that easily leads to rivalry with the model whose desire one imitates. This bears on the question of hominization inasmuch as culture became necessary for survival precisely when the instinctive dominance-submission mechanisms that served to curtail violence in the animal kingdom proved inadequate to that task in the case of a creature endowed with seemingly insatiable, metaphysical, and fickle desires, all too prone to replicate the desires of others.

Human desire, Girard argues, is always aroused, redirected, and intensified by the desire of another. We desire what we see another desiring, striving to obtain, or enjoying.

Bouyer's journey from Lutheran pastor to Ressourcement theologian

Bouyer's journey from Lutheran pastor to Ressourcement theologian | Dr. Christopher Shannon | CWR

A new English translation of the Memoirs of Fr. Louis Bouyer offers keen insights into the Church, the Second Vatican Council, and the intellectual landscape of the past century

The ressourcement movement is arguably the most significant Catholic theological tradition of the twentieth century. Its thinkers figured prominently in shaping many of the documents of the Second Vatican Council; one of its brightest lights became Pope Benedict XVI. For all of this, it remains largely unknown among Catholics outside of the small circle gathered around the journal Communio. In the stormy decades following Vatican II, thinkers on both the left and the right found reasons for dismissing ressourcement theology: left-liberals found it too conservative, while conservative-traditionalists thought it too liberal.

In America, lack of understanding of its theology has been surpassed only by ignorance of its theologians. Despite the translation of many of the major works of this predominantly francophone movement, there are few if any historical-biographical studies in English of individual theologians or the movement as a whole. Given this state of affairs, we are all indebted to Ignatius Press for publishing a new English translation of the memoirs of one of the leading ressourcement theologians, Louis Bouyer.

Perhaps less well known today than as thinkers such as Henri de Lubac and Hans Urs von Balthasar, Bouyer was in his time a pioneer in bringing new developments in European Catholic thought to America. A leading voice in the mid-twentieth century liturgical movement, he participated in the early American forays into liturgical renewal sponsored by the University of Notre Dame. Of all the ressourcement thinkers, Bouyer was perhaps the one most engaged with the English-speaking Catholic world. Much of this attraction may be traced to his fascination with the life and work of John Henry Newman, which in turn reflects in no small way Bouyer's standing as himself a famous intellectual convert to Catholicism.

Born in Paris in 1913, raised in a religiously and ethnically mixed French Protestant milieu, Bouyer found himself as a young man drawn to a group of earnest Protestants seeking some alternative to the stale liberal Protestantism of the nineteenth century; like Newman a century earlier, this search lead him first to ordained ministry in the way station of high church Protestantism (in his case, Lutheranism), and ultimately to the Roman Catholic Church. Like Newman's Apologia, Bouyer's Memoirs offers a first-person account of a highly intellectualized spiritual transformation that is at the same time a moving portrait of the web of friendships and relationships inextricably bound up with that very personal conversion. Spared the need to defend himself against calumnies heaped upon him by pre-conversion confidents, Bouyer writes nonetheless in part to vindicate his pre-conversion years, insisting throughout on the enduring truth of those aspects of Protestantism common to all Christians yet sadly neglected by the Church in the first half of the twentieth century, most especially the Bible and the liturgy.

Readers looking for a guide to the intellectual landscape of this period should be advised: the book is, as its title indicates, a memoir, not a history, and certainly not a theological treatise. In this respect, it offers first of all a rich and revealing glimpse into a lost European world, a time before the World Wars, death camps and the global triumph of American commercial culture. More precisely, in his account of his early childhood years in Paris, he gives us a portrait of a world on the verge of transformation, the last days of la belle epoque:

November 3, 2015

Daniel and the Great Unveiling

Prophet Daniel (c. 1542–1545) on the Sistine Chapel ceiling, by Michelangelo (Wikipedia.org)

Daniel and the Great Unveiling | Bishop Robert Barron | CWR's The Dispatch

When Jesus came preaching precisely the kingdom of God, we should not be surprised that people took him to be announcing the fulfillment of the Daniel prophecy

Toward the end of the liturgical year, we Catholics hear at Mass from the mysterious, often confounding, and utterly fascinating book of Daniel. Recent scholarship has demonstrated that the book of Daniel had an extraordinarily powerful influence on the first Christians, providing them a most important template for understanding the significance of Jesus. Daniel is, of course, an example of apocalyptic literature, which in the common understanding means that it has to do with the end of the world. Well, yes and no. The word "apocalypse" carries the sense of unveiling, literally taking back the kalumna (veil). This is why, when the early translators rendered the term in Latin, they chose "revelatio" (removing the velum, unveiling). Apocalyptic books, therefore, reveal something of decisive significance. They display a hidden truth, indeed raising the curtain on a new world.

The book under consideration is famous, of course, for its memorable narratives of Daniel in the lion's den, of the three young men who are thrown into the furnace but who survive through God's grace, of the handwriting on the wall, and of the rape of Susannah. But it is also a book of visions, dreams, and their interpretation, for Daniel is something like Joseph in the book of Genesis, an inspired solver of puzzles. In the second chapter of the book of Daniel, we hear of a dream dreamt by King Nebuchadnezzar. In his night vision, the king saw a statue made of a variety of substances: its head of gold, its breast and arms of silver, its belly and thighs of brass, and its feet of clay. He then saw a stone, not hewn by a human hand, crash into the statue and shatter it to pieces.

None of the king's wise men and soothsayers could interpret the dream, but Daniel, an Israelite from the community of exiles, was able to read it.

New: "The Soul's Upward Yearning: Clues to Our Transcendent Nature from Experience and Reason"

Now available from Ignatius Press:

The Soul's Upward Yearning Clues to Our Transcendent Nature from Experience and Reason

by Fr. Robert Spitzer, SJ

Since the early twentieth century, scientific materialism has so undermined our belief in the human capacity for transcendence that many people find it difficult to believe in God and the human soul. The materialist perspective has not only cast its spell on the natural sciences, psychology, philosophy, and literature, it has also enthralled popular culture, which offers very little to encourage the “soul’s upward yearning”.

There are many signs of the widespread loss of confidence in our ability to soar upward, and these have been noted by thinkers as diverse as Carl Jung (psychiatrist), Mircea Eliade (historian of religion), Gabriel Marcel (philosopher), and authors C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien. Their observations were validated by a 2004 study published in the American Journal of Psychiatry that linked the absence of religion with a marked increase in suicide, meaninglessness, substance abuse, separation from family members, and other psychological problems.

Thus, the loss of transcendence is negatively affecting an entire society. It is stealing from countless individuals their sense of happiness, dignity, ideals, virtues, and destiny.Ironically, the evidence for transcendence is greater today than in any other period in history. The problem is, this evidence has not been compiled and made widely available—a challenge Father Spitzer aspires to meet with this book.

Father Spitzer’s work provides a bright light in the midst of the darkness by presenting traditional and contemporary evidence for God and a transphysical soul from several major sources. It shows that we are transcendent beings with souls capable of surviving bodily death; that we are self-reflective beings aware of and able to strive toward perfect truth, love, goodness, and beauty; that we have the dignity of being created in the very image of God. If we underestimate these truths, we undervalue one another, underlive our lives, and underachieve our destiny.

Fr. Robert Spitzer, SJ, is a philosopher, educator, author and former President of Gonzaga University. He is founder and President of the Magis Institute, an organization dedicated to public education on the relationship among the disciplines of physics, philosophy, reason, and faith. He is the head of the Ethics and Performance Institute which delivers web-based ethics education to corporations and individuals. He is also President of the Spitzer Center of Ethical Leadership, which delivers similar curricula to non-profit organizations. His other books include Healing the Culture and Five Pilars of the Spiritual Life.

Praise for The Soul's Upward Yearning:

“Father Spitzer displays a broad range of arguments in favor of the reality and the compelling importance of the transcendent dimension of our existence on the basis of religious literature, our interior awareness of transcendent reality, the cosmic struggle between good and evil, metaphysics, our natural desire to experience perfect goodness, love and beauty, the evidence of near-death experiences, and contemporary science, especially astrophysics.” -- Timothy Cardinal Dolan, Archbishop of New York

“Spitzer’s brilliant use of physics, cosmology, psychology, neuroscience, NDE studies, and contemporary philosophy reveals how all disciplines and shared human experiences converge on the truth of our spiritual nature. A grand synthesis from the pen of a master.” -- Michael Augros, Ph.D., Author, Who Designed the Designer?

“An intellectual triumph. Those who think faith is a matter of emotion and self-delusion could not intelligently defend that position if they read this book with an open mind and comprehended its arguments. Magnificent.” -- Dean Koontz, #1 New York Times Best-Selling Author

November 1, 2015

Two Years Among the Liberal Theologians

St. Ignatius Gate entrance at Boston College (Photo: Boston_Starbucks_Rebel / Wikipedia)

Two Years Among the Liberal Theologians | Dorothy Cummings McLean | Catholic World Report

The brain-blowing combination of asserting that what is not Catholic teaching is somehow Catholic teaching and then shrieking like a frightened schoolgirl when the word "heresy" is uttered is what the American Catholic/Jesuit theological academy is all about

Once, I was a theologian.

But, to tell you the truth, as a believing Catholic who seeks to understand what it is she believes, I am still a theologian. I was taught this on the first day of my "Method in Theology" class in Toronto, and it wrote itself permanently on my heart. All believing Catholics who seek to understand what it is they believe are Catholic theologians, which means that Ross Douthat is a Catholic theologian. His academic critics are ... academics. Some of them may be Catholic theologians, but I wouldn't assume that—especially not if they got their training at Boston College.

"Own your heresy" tweeted Douthat, and Father James Martin, SJ seemed to throw up his hands in holy horror. Oh, how irresponsible! Oh, how potentially damaging to a career! Oh, how the CDF will swoop down like a wolf upon the fold. Except it won't, and it almost never does—and they're too busy packing up Monsignor Charamsa's office right now anyway.

The brain-blowing combination of asserting that what is not Catholic teaching is somehow Catholic teaching and then shrieking like a frightened schoolgirl when the word "heresy" is uttered is what the American Catholic/Jesuit theological academy is all about, and I should know. I was in it for two of the most miserable years of my life.

As the Affair Douthat unfolds, I keep attaching faces to the names I hadn't heard or seen for many years. One of them belongs to an active homosexual who brought his boyfriend along on the departmental retreat and shared a room with him. Another belongs to an active unmarried heterosexual who brought his girlfriend along on the departmental retreat and shared a room with her. They were both very pleasant and cheerful men. I liked them very much—which does not erase the facts that they did not believe the teaching of the Catholic Church concerning sexual morality and that today they are professional Catholic theologians.

Boston College. It's been ten years since I first turned up for "Accepted Students Day", and eight years since I left with my professional hopes in tatters, but the very name still plunges me into depression. The contrast between the loving, thoughtful environment of my Canadian theologate and the neurotic, boastful, overrated, double-faced snake pit that was the Boston College theology department transformed me from one of the "rock stars" of my Canadian college—successfully juggling coursework and three jobs, graduating magna cum laude—into a hysterical wreck, unable to read print.

Saint Ignatius of Loyola composed a prayer that begins, "Take, Lord, my liberty, my understanding, my entire will". In the post-Vatican II era it was set to a jolly tune, and I had sung it blithely in Toronto without the slightest clue what losing one's understanding might mean. In my case it meant forcing myself, in agony, to make the little black marks on the page make sense and then exploding in fury when the document before me was merely some speculative nonsense about a "Markian" community that may or may not have existed. "Might", "should", "it could be": the weasel words of academia.

I had worked enormously hard to get to Boston College—three years of busting my brain and non-stop reading, writing, volunteering, ministry placements, jobs—and I had loved it. When I got the phone call on February 24, 2005 telling me I had been accepted for the Boston College PhD program in theology, my heart ached with joy. My life—I was still a single woman then—was finally on track: I would finish my PhD, get a job in a Jesuit college, walk forever in the groves of academe, well paid, serving God doing what I loved best.

Reality slapped me in the face when I arrived for "Accepted Students Day"—April 1, I believe. April Fool's Day.

Carl E. Olson's Blog

- Carl E. Olson's profile

- 20 followers