Carl E. Olson's Blog, page 255

December 19, 2011

Archbishop Fulton Sheen on the final days of Advent

Archbishop Fulton Sheen on Advent and the Christmas Mystery

Through the Year with Fulton Sheen is Sheen at his best—the master storyteller, preacher, and faithful servant of Christ—with a word of encouragement, counsel, and direction for each day of the year. With characteristic insight and eloquence, he penetrates to the heart of the Christian life with practical reflections on love, holiness, spiritual power, miracles, and Christ-like living. These daily selections provide a fresh perspective on what it means to be a follower of Christ, on the challenge of serving God and the blessings of living a grace-filled life.

Here are the daily selections for the final days of Advent.

Nuptials | December 19

What is the idea that runs all through scripture? It is nuptials. The  covenant is based on nuptials. As we used to say in the old marriage ceremony, "Not even the flood took it away, not even sin." There was the nuptials of man and woman in the garden of Eden, the nuptials of Israel and God in the Old Testament. In the prophet Hosea: "I your Creator am your husband." God is the husband of Israel.

covenant is based on nuptials. As we used to say in the old marriage ceremony, "Not even the flood took it away, not even sin." There was the nuptials of man and woman in the garden of Eden, the nuptials of Israel and God in the Old Testament. In the prophet Hosea: "I your Creator am your husband." God is the husband of Israel.

In that beautiful passage of the book of Hosea, God tells Hosea to marry a prostitute, a worthless woman. She leaves him, betrays him, commits adultery, has children by other men, and when the heart of Hosea is broken, God says, "Hosea, take her back, take her back. She's the symbol of Israel. Israel has been my unworthy spouse, but I love Israel, and I will never let her go." Hosea taking back the prostitute is the symbol of God's love for his qahal, his church of the Old Testament. Now we come to new nuptials, the nuptials of divinity and humanity in our Blessed Mother.

Why Christ came to earth | December 20

You may remember from Shakespeare the famous speech of Mark Anthony over Caesar. He said, "I will show you sweet Caesar's wounds, poor, poor dumb mouths and bid them speak for me." Instead of showing you Caesar's wounds, I shall show you the wounds of Christ, who is both God and man, the only one who ever came to this earth to die and to conquer it. You and I came into the world to live; he came into the world to offer his life for us. And so he founded a new type of religion.

All other religions, without exception, go from man to God, either by contemplation or by a kind of mortification and self-denial. One, for example, is the eightfold path of Buddha. But with our Blessed Lord, religion comes from God to man. We need help and, particularly, redemption from sin.

Nature is in childbirth | December 21

In this late day of creation we are troubled by pollution, and nature seems to turn against us. Will nature ever be completely liberated? Yes. Scripture tells us it is waiting for the liberation of the sons of God. When the number of the elect is completed, then there will be a new heaven and a new earth. St. Paul has a beautiful description of that in the eighth chapter of Romans. "For the created universe waits with eager expectation for God's Son to be revealed. It was made the victim of frustration, not by its own choice."

Nature did not become rebellious because it willed it, but because of him who made it so-because of us. And always there was hope, because the universe itself is to be freed from the shackles of mortality and enter upon the liberty and splendor of the children of God. "Up to the present, we know, the whole created universe groans in all of its parts, as if in the pangs of childbirth." just think of it. We hardly think of nature that way. No poet has ever sung about nature being like a woman in childbirth. And yet here it is. We can hardly wait. Each sunrise, each sunset: nature is expectant. When will men serve God and the number of the elect be complete?

Heaven was not empty | December 22

When we say that God became man, we do not mean to say that heaven was empty. That would be to think of heaven as a kind of a space, like a room that was twenty by thirty feet. When God came to this world, he did not leave heaven empty. When he came to this world, he was not shaved down, whittled down to human proportions. Rather, Christ was the life of God dwelling in human flesh. St. Thomas Aquinas includes a very beautiful description of this in one of his hymns. He said, "The heavenly Word proceeding forth, yet leaving not the Father's side."

One chance in millions | December 23

A Jewish scholar who became a Christian and who knew the Old Testament very well and all of the traditions of the Jews, said that at the time of Christ the rabbis had gathered together 456 prophecies concerning the Messiah, the Christ, the conqueror of evil who was to be born and to enter into a new covenant with mankind. Suppose the chances of any one prophecy being fulfilled by accident, say the place where he would be born, was one in a hundred.

Then, if two prophecies were fulfilled, the chances would be one in a thousand. If three prophecies were to coincide in Christ, that would be one in ten thousand. If four, one in a hundred thousand. If five, one in a million. Now if all of these prophecies were fulfilled in Christ, what would be the chance of them all concurring at the appointed moment, not only in place but also in time, as was foretold by the prophet Daniel? Take a pencil and write on a sheet of paper the numeral 1, and draw a line beneath it. Under the line write 84, and after 84, if you have time, write 126 zeros. That is the chance of all of the prophecies of Christ being fulfilled. It runs into millions and millions, trillions and trillions.

No room in the inn | December 24

Mary is now with child, awaiting birth, and Joseph is full of expectancy as he enters the city of his own family. He searched for a place for the birth of him to whom heaven and earth belonged. Could it be that the Creator would not find room in his own creation? Certainly, thought Joseph, there would be room in the village inn. There was room for the rich; there was room for those who were clothed in soft garments; there was room for everyone who had a tip to give to the innkeeper.

But when finally the scrolls of history are completed down to the last word of time, the saddest line of all will be: "There was no room in the inn." No room in the inn, but there was room in the stable. The inn was the gathering place of public opinion, the focal point of the world's moods, the rendezvous of the worldly, the rallying place of the popular and the successful. But there's no room in the place where the world gathers. The stable is a place for outcasts, the ignored and the forgotten. The world might have expected the Son of God to be born in an inn; a stable would certainly be the last place in the world where one would look for him. The lesson is: divinity is always where you least expect to find it. So the Son of God made man is invited to enter into his own world through a back door.

Now we come to what our Lord said about heaven. It was the night of the Last Supper. Jesus gathered about him all his apostles-poor, weak, frail men. He washed their feet. He was facing the agony in the garden, and that terrible betraying kiss of Judas, and even the denial of Peter himself. One would think that all the talk would be about himself. Certainly, when we have trials, that is what we think about. But our Lord thought about the apostles. He saw the sadness in their faces, and he said, "Be not troubled, do not be sad, I go to prepare a place for you. In my father's house there are many mansions." How did he know about the Father's house? He came from there. That was his home. Now preparing to go back home, he tells them about the Father's house and he says, "I go to prepare a place for you."

God never does anything for us without great preparation. He made a garden for Adam, as only God knows how to make a garden beautiful. Then, when the Jews came into the promised land, he prepared the land for them. He said he would give them houses full of good things, houses which they never built. He said that he would give them vineyards and olive trees which they never planted. just so, he goes to prepare a place for us. Why? Simply because we were not made for heaven; we were made for earth. Man, by sin, spoiled the earth, and God came down from heaven in order to help us remake it. After having redeemed us, he said that he would now give us heaven, so we got all this: the earth, and heaven too.

Related Ignatius Insight Articles and Excerpts:

• The God in the Cave | G.K. Chesterton

• The Incarnation | Frank Sheed

• The Perfect Faith of the Blessed Virgin | Carl E. Olson

• Mary Immaculate | Fr. Kenneth Baker, S.J.

• Immaculate Mary, Matchless in Grace | John Saward

• The Mystery Made Present To Us | Fr. Alfred Delp, S.J.

• "Born of the Virgin Mary" | Paul Claudel

• The Old Testament and the Messianic Hope | Thomas Storck

• "Conceived by the Holy Spirit, born of the Virgin Mary" | Hans Urs von Balthasar

Archbishop Fulton Sheen (1895-1979) is considered by many to be the most influential Catholic of the 20th century in America. Millions of people watched his incredibly popular television series every week, "Life is Worth Living", and millions more listened to his radio program, "The Catholic Hour". Wherever he preached in public, standing-room-only crowds packed churches and halls to hear him. He had the same kind of charisma and holiness that attracts so many people to Pope John Paul II, who called Sheen "a loyal son of the Church."

Archbishop Fulton Sheen (1895-1979) is considered by many to be the most influential Catholic of the 20th century in America. Millions of people watched his incredibly popular television series every week, "Life is Worth Living", and millions more listened to his radio program, "The Catholic Hour". Wherever he preached in public, standing-room-only crowds packed churches and halls to hear him. He had the same kind of charisma and holiness that attracts so many people to Pope John Paul II, who called Sheen "a loyal son of the Church."

Sheen was a prolific author whose books included his Life of Christ, The Priest Is Not His Own, The World's First Love, and his autobiography, Treasure In Clay.

December 18, 2011

How good is the Pope's health?

For a man who will be 85 in April 2012, and who has quite the busy schedule, Benedict XVI is doing well. But he is not, of course, as vigorous and busy as he was a few years ago. An Associated Press piece, "Pope heads into busy Christmas season tired, weak", contains a sprinkling of information, a dash or two of rumor, and a cup or three of speculation, with several references to the "r" word:

Vatican spokesman the Rev. Federico Lombardi has said no medical condition prompted the decision to use the moving platform in St. Peter's, and that it's merely designed to spare the pontiff the fatigue of the 100-meter (-yard) walk to and from the main altar.

And Benedict rallied during his three-day trip to Benin in west Africa last month, braving temperatures of 32 Celsius (90F) and high humidity to deliver a strong message about the future of the Catholic Church in Africa.

Wiping sweat from his brow, he kissed babies who were handed up to him, delivered a tough speech on the need for Africa's political leaders to clean up their act, and visited one of the continent's most important seminaries.

Back at home, however, it seems the daily grind of being pope - the audiences with visiting heads of state, the weekly public catechism lessons, the sessions with visiting bishops - has taken its toll. A spark is gone. He doesn't elaborate off-the-cuff much anymore, and some days he just seems wiped out.

Take for example his recent visit to Assisi, where he traveled by train with dozens of religious leaders from around the world for a daylong peace pilgrimage. For anyone participating it was a tough, long day; for the aging pope it was even more so. ...

Yet Benedict himself raised the possibility of resigning if he were simply too old or sick to continue on, when he was interviewed for the book "Light of the World," which was released in November 2010.

"If a pope clearly realizes that he is no longer physically, psychologically and spiritually capable of handling the duties of his office, then he has a right, and under some circumstances, also an obligation to resign," Benedict said. ...

Benedict said in "Light of the World" that he knew his own strength was diminishing - steps are difficult for him and his aides regularly hold his elbows as he climbs up or down. But at the same time Benedict insisted that he had no intention of resigning to avoid dealing with the problems of the church, such as the sex abuse scandal.

"One can resign at a peaceful moment or when one simply cannot go on. But one must not run away from danger and say that someone else should do it," he said.

As a result, a papal resignation anytime soon seems unlikely.

December 17, 2011

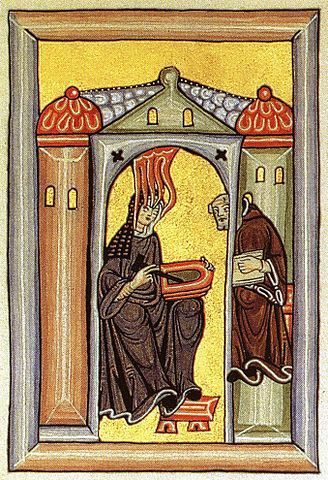

Benedict XVI to name fourth female Doctor of the Church in 2012

:

Benedict XVI is set to appoint Hildegard of Bingen as a Doctor of the Church in October of 2012. She was a German Benedictine nun and  was known for her visions and prophecies.

was known for her visions and prophecies.

Hildegard of Bingen lived in the twelfth century. In addition to being a nun, she was a composer, philosopher, physicist and ecologist. A multi-talented woman, and a pioneer for many of these fields during the Middle Ages.

She came from a wealthy family and when she was only eight years old was sent to study in a monastery. She eventually decided to become a nun and later became an abbess.

Her visions and prophecies were recognized by the pope during that time, allowing her to speak about them publicly.

Since she has not been officially canonized, the ceremony is likely to take place before the pope names her as a Doctor of the Church in October.

Benedict XVI dedicated several of his general audiences to this German nun, saying that she "served the Church in an age in which it was wounded by the sins of priests and laity".

And from Benedict XVI's September 8, 2010, general audience:

The popularity that surrounded Hildegard impelled many people to seek her advice. It is for this reason that we have so many of her letters at our disposal. Many male and female monastic communities turned to her, as well as Bishops and Abbots. And many of her answers still apply for us. For instance, Hildegard wrote these words to a community of women religious: "The spiritual life must be tended with great dedication. At first the effort is burdensome because it demands the renunciation of caprices of the pleasures of the flesh and of other such things. But if she lets herself be enthralled by holiness a holy soul will find even contempt for the world sweet and lovable. All that is needed is to take care that the soul does not shrivel" (E. Gronau, Hildegard. Vita di una donna profetica alle origini dell'età moderna, Milan 1996, p. 402). And when the Emperor Frederic Barbarossa caused a schism in the Church by supporting at least three anti-popes against Alexander iii, the legitimate Pope, Hildegard did not hesitate, inspired by her visions, to remind him that even he, the Emperor, was subject to God's judgement. With fearlessness, a feature of every prophet, she wrote to the Emperor these words as spoken by God: "You will be sorry for this wicked conduct of the godless who despise me! Listen, O King, if you wish to live! Otherwise my sword will pierce you!" (ibid., p. 412).

With the spiritual authority with which she was endowed, in the last years of her life Hildegard set out on journeys, despite her advanced age and the uncomfortable conditions of travel, in order to speak to the people of God. They all listened willingly, even when she spoke severely: they considered her a messenger sent by God. She called above all the monastic communities and the clergy to a life in conformity with their vocation. In a special way Hildegard countered the movement of German cátari (Cathars). They cátari means literally "pure" advocated a radical reform of the Church, especially to combat the abuses of the clergy. She harshly reprimanded them for seeking to subvert the very nature of the Church, reminding them that a true renewal of the ecclesial community is obtained with a sincere spirit of repentance and a demanding process of conversion, rather than with a change of structures. This is a message that we should never forget. Let us always invoke the Holy Spirit, so that he may inspire in the Church holy and courageous women, like St Hildegard of Bingen, who, developing the gifts they have received from God, make their own special and valuable contribution to the spiritual development of our communities and of the Church in our time.

"Hail! tabernacle of God and the Word!"

A Scriptural Reflection on the Readings for Sunday, December 18, 2011, the Fourth Sunday of Advent | Carl E. Olson

Readings:

• 2 Sm 7:1-5, 8b-12, 14a, 16

• Ps 89:2-3, 4-5, 27, 29

• Rom 16:25-27

• Lk 1:26-38

"Hail! tabernacle of God and the Word. Hail! holy beyond all holy ones. Hail! ark gilded by the Holy Ghost. Hail! unfailing treasure-house of life."

These words from the ancient Akathist hymn, a great sixth-century song of praise for the mystery of the Incarnation, poetically summarize the Marian themes in today's readings. The Theotokos—the Mother of God—is the dwelling place of God, the "container of the Uncontainable God," and "the womb of God enfleshed."

Many of the early Church fathers spoke of Mary as the new ark of the covenant. "Mary, in whom the Lord himself has just made his dwelling," the Catechism remarks, "is the daughter of Zion in person, the ark of the covenant, the place where the glory of the Lord dwells" (par. 2676). The ark of the covenant, described in Exodus 25, was a gold-plated wooden chest containing holy objects, including some manna, Aaron's rod, and a copy of the covenant between God and Israel (Heb. 9:4-5). Its lid, the mercy seat, was made of gold and adorned with two cherubim, representing the throne of God.

For a long time the ark was kept in a mobile tabernacle. Eventually, as we hear in today's first reading, King David desired to build a permanent house, or temple, for the ark. In responding to David, the Lord made clear that the only one who could build an everlasting house for God is God himself; he promised to eventually "raise up" an heir who would establish an everlasting throne and kingdom.

The raising up of an heir was realized in the coming down of the Son through the mystery of the Incarnation—"the mystery kept secret for long ages," in the words of Saint Paul. The King of kings and Lord of lords rested within the throne of a womb; the Creator of all things visible was carried, invisible, within the Virgin; the Conqueror of sin and death was kept and concealed within the Blessed Mother.

"Hail! O you who have become a kingly Throne. Hail! O you who carries Him Who carries all! Hail, O Star who manifests the Sun. Hail! O Womb of the Divine Incarnation!"

Mary, created without sin, finding favor with God, and accepting in faith the call of the Lord, became a living, breathing ark of the covenant. "Full of grace, Mary is wholly given over to him who has come to dwell in her and whom she is about to give to the world" (CCC 2676). As God once dwelt in the tabernacle among a nomadic people, he now comes to dwell, through a singular woman, among men—pilgrims journeying toward their heavenly home. "For the first time in the plan of salvation and because his Spirit had prepared her, the Father found the dwelling place where his Son and his Spirit could dwell among men" (CCC 721).

David longed to build a temple and his son Solomon did build the temple, but only God could and did create a sinless, human temple.

Only God, because of his power and love, could become so small and humble so that he might save us. It is God who reaches out, who dwells among man, who becomes flesh and blood for our sake. Nothing, the angel Gabriel explains to the young Jewish virgin, "will be impossible for God."

"May it be done to me according to your word." With those words, Mary demonstrated the proper response to God, bursting with quiet faith and trusting reception. Opening herself to God's word, she was filled with the Word who is God. Filled with the Holy Spirit, she became the throne of God.

"Behold," exclaims the Akathist hymn, "heaven was brought down to earth when the Word Himself was fully contained in you! Now that I see Him in your womb, taking a servant's form, I cry out to you in wonder: Hail, O Bride and Maiden ever-pure!" During Christmas we cry out in wonder at the work of God and the faith of his mother.

(This "Opening the Word" column originally appeared in the December 21, 2008, edition of Our Sunday Visitor newspaper.)

December 16, 2011

Watch the trailer for "Mother Teresa of Calcutta: A Personal Portrait"

Also see these excerpt from the book, Mother Teresa of Calcutta—A Personal Portrait: 50 Inspiring Stories Never Before Told, by Monsignor Leo Maasburg:

T. S. Eliot's distrust of secular humanism and disdain for empty words

T. S. Eliot is my favorite poet and the fine philosopher Roger Scruton is always worth reading, so this lengthy Scruton essay on Eliot (originally published in The Intercollegiate Review in 2008) is, not surpringly, a very helpful guide to the thought and work of Eliot. This passage has some good food for thought about modernity, language, and heresy:

Eliot's deep distrust of secular humanism – and of the socialist and democratic ideas of society which he believed to stem from it – reflected his critique of the neo-romantics. The humanist, with his myth of man's goodness, is taking refuge in an easy falsehood. He is living in a world of make-believe, trying to avoid the real emotional cost of seeing things as they are. His vice is the vice of Edwardian and "Georgian" poetry – the vice of sentimentality, which causes us not merely to speak and write in clichés, but to feel in clichés too, lest we should be troubled by the truth of our condition. The task of the artistic modernist, as Eliot later expressed it, borrowing a phrase from Mallarmé, is "to purify the dialect of the tribe": that is, to find the words, rhythms, and artistic forms that would make contact again with our experience – not my experience, or yours, but our experience, the experience that unites us as living here and now. And it is only because he had captured this experience – in particular, in the bleak vision of The Waste Land – that Eliot was able to find a path to its meaning.

He summarizes his attitude to the everyday language of modern life and politics in his essay on the Anglican bishop Lancelot Andrewes, and it is worth quoting the passage in full:

To persons whose minds are habituated to feed on the vague jargon of our time, when we have a vocabulary for everything and exact ideas about nothing – when a word half-understood, torn from its place in some alien or half-formed science, as of psychology, conceals from both writer and reader the utter meaninglessness of a statement, when all dogma is in doubt except the dogmas of sciences of which we have read in the newspapers, when the language of theology itself, under the influence of an undisciplined mysticism of popular philosophy, tends to become a language of tergiversation – Andrewes may seem pedantic and verbose. It is only when we have saturated ourselves in his prose, followed the movement of his thought, that we find his examination of words terminating in the ecstasy of assent. Andrewes takes a word and derives the world from it. . . .[1]

For Eliot, words had begun to lose their precision – not in spite of science, but because of it; not in spite of the loss of true religious belief, but because of it; not in spite of the proliferation of technical terms, but because of it. Our modern ways of speaking no longer enable us to "take a word and derive the world from it": on the contrary, they veil the world, since they convey no lived response to it. They are mere counters in a game of cliché, designed to fill up the silence, to conceal the void which has come upon us as the old gods have departed from their haunts among us.

That is why modern ways of thinking are not, as a rule, orthodoxies, but heresies – a heresy being a truth that has been exaggerated into falsehood, a truth in which we have taken refuge, so to speak, investing in it all our unexamined anxieties and expecting from it answers to questions which we have not troubled ourselves to understand. In the philosophies that prevail in modern life – utilitarianism, pragmatism, behaviorism – we find that "words have a habit of changing their meaning. . .or else they are made, in a most ruthless and piratical manner, to walk the plank." The same is true, Eliot implies, whenever the humanist heresy takes over: whenever we treat man as God, and so believe that our thoughts and our words need be measured by no other standard but themselves.

Very much along the same lines as the arguments presented in Abuse of Language, Abuse of Power, by Joseph Pieper. A fine book on Eliot, specifically on his Four Quartets, is Dove Descending: A Journey Into T.S. Eliot's Four Quartets, by Thomas Howard. Here is part of my 2006 interview with Dr. Howard about his book:

IgnatiusInsight.com: How did Eliot, via his poetry and critical works, influence other poets and writers? What has been his impact on poetry?

IgnatiusInsight.com: How did Eliot, via his poetry and critical works, influence other poets and writers? What has been his impact on poetry?

Howard: Eliot had a vast influence for several decades in the English-speaking world, during which he enjoyed an eminence that few writers achieve during their lifetime. But it gradually dawned on the academic world and the world of the arts that Eliot was extolling an unabashedly Christian vision of things, and he was virtually exiled from English departments. He said things that the 20th century did not at all like to hear, most notably that undiluted Christian orthodoxy judges the whole modern enterprise.

IgnatiusInsight.com: Why should Eliot be read today?

Howard: Why read Eliot now? Because he speaks of what he called "the permanent things."

IgnatiusInsight.com: How would you describe the significance and value of Four Quartets? Is this poem a good place to first meet Eliot for those who haven't read his work before?

Howard: In my opinion, Four Quartets should take its place with other monuments that bespeak the Christian vision, e.g., Dante's work, Chartres cathedral, Bach's B-minor Mass, Mozart's Requiem, and van Eyck's painting of The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb. But there is no easy "starting point" for one approaching Eliot's work. It is as difficult as scaling Everest–and at least as rewarding. But a new reader needs some help.

Read the entire interview; you can also read Fr. George Rutler's Foreword to Howard's book, "The Quintessential – And Last – Modern Poet", which contains this beautiful passage: "In Four Quartets, Eliot comes to the modernist's lattice window like the lover in the Song of Solomon, furtively chanting a benign proposal of which all this world's lights and shadows are intimations, and in his precise and occasionally affected diction he witnesses to the Doctors of the Church in this: the intellect is supernaturally perfected by the light of glory."

Introduction to Abbot Vonier's "The Life of the World to Come", by Edward T. Oakes, S.J.

Introduction to Abbot Vonier's The Life of the World to Come | Edward T. Oakes, S.J. | Ignatius Insight

What distinguishes a Christian from a non-Christian? Perhaps behavior? No. Given the record of Christian sinfulness, history shows that virtues and vices can be found across the whole spectrum of human society. Who after all has a monopoly on vice or virtue? Where Christians have St. Francis of Assisi, Hindus have Mahatma Gandhi, and atheists Albert Camus.

Still, behavior must count for something, no? For when we grant that some Christians act disgracefully, we are already implying that some behaviors are incompatible  with the faith. But if we then go on to assert that therefore behavior alone distinguishes the true from the false Christian, we run into the difficulty noted above: history knows of both Christian vices and non-Christian virtues.

with the faith. But if we then go on to assert that therefore behavior alone distinguishes the true from the false Christian, we run into the difficulty noted above: history knows of both Christian vices and non-Christian virtues.

Maybe, though, Christianity defines virtuous behavior in a way unique to itself. Indeed it does. In fact, one of the many merits of Abbot Vonier's short book, The Life of the World to Come, is his insistence that Christians necessarily see virtue differently from other religions and worldviews. Specifically, they acknowledge three key theological virtues above all: faith, hope, and love. One might object that other religions know of faith, hope, and love too, as they surely do; but Abbot Vonier will insist that the content of these virtues is utterly unique in the Christian understanding, and that holds true most especially the content of the Christian hope.

Given that fact, it seems odd how little theologians concentrate on the virtue of hope, at least in contrast to the other two theological virtues. Because St. Paul defined love as the greatest of the virtues, and because secular culture makes a life of faith so challenging in the contemporary setting, most theologians concentrate on faith and charity, as in Pope Benedict XVI's first encyclical, Deus Caritas Est (on love), or his famous book Introduction to Christianity (on faith). But if the net result of this concentration ends up slighting the virtue of hope, something essential is lost.

But what is the specifically Christian hope? St. Paul defines it this way: "If then you have been raised with Christ, seek the things that are above, where Christ is, seated at the right hand of God. Set your minds on things that are above, not on things that are on earth. For you have died, and your life is hid with Christ in God. When Christ who is our life appears, then you also will appear with him in glory" (Colossians 3:1-4). In this passage Paul gives us his answer to the question asked above. Here we have, neatly formulated, at least one of the great marks that can help us distinguish the (authentic) Christian from the (virtuous) non-Christian: for true Christians, heaven should be more real than the earth on which they dwell.

In essence, Abbot Vonier's book, now before the reader in a new edition from Zaccheus Press after long having languished out of print, is an extended meditation on this maxim. First of all, as the title clearly indicates, the author insists that our hope does not terminate in heaven alone but, as the Creed says, in vitam venturi saeculi—that is, the Christian hopes for the life of the world to come, when there will be a "new heaven and a new earth" (Revelation 21:1).

Too often in the past, the focus of Christians had been one of, as they say, just "getting into heaven," an attitude that turns the sacraments into a kind of celestial life-insurance premium. True, as St. Paul says above, while we are still sojourning on this earth, we are called to focus on heaven (which is why a cultivation of friendship with the saints is so important to the devout life). But our ultimate hope is for the final restoration of all things into a new heaven and a new earth, with the resurrection of our bodies a key part of that hope.

So much for the content of our hope, what the medieval scholastics called spes quod. But what about the subjective state of hope, the spes qua, as it were? Is there something uniquely Christian here too? Again, Abbot Vonier illuminates the difference admirably in a passage so lucid that it bears quoting in full (not least because I hope it will motivate the reader to read the whole book!):

There is, then, this deep note of assurance and joy in our spiritual longings; instead of saying that we hope to have eternal life, we are made to say [in the Creed] that we await the life of the world to come. Hoping for something is profoundly different from waiting for something. You wait for a train; you hope for fine weather. The train is sure to arrive; if you are early you sit down and feel the contentment of certainty. But if you are bent on pleasure your hope of a fine day has a disturbing element of doubt; you are not quite certain whether the fine weather will hold. Hope is a very different thing from expectation. There is in hope an element of uncertainty, a kind of struggle; we have to work ourselves up to it when we hope earnestly.

The Swiss Catholic theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar once dryly observed that the real reason most nonbelievers won't make the leap of faith and accept the Christian message is because they are afraid that, deep down, it sounds simply too good to be true. Physics teaches entropy; Christians proclaim their revelation that earth will someday be transformed into heaven. Modern Stoics like Sigmund Freud, borrowing a page from Marcus Aurelius' Meditations, teach resignation in the face of inevitable death; Christians hold out hope for a resurrection of the body. In other words, as the Abbot rightly says, "spes est boni ardui: hope strains for what is difficult, arduous." And why so difficult? Because we are called "to possess now the life of God in our frail, poor souls, so much inclined to the life of sin. Incredible as it seems, in spite of all appearances to the contrary, through hope we feel confident that God's life is in us" even in the midst of all contradictory evidence (emphasis added).

The great marvel of this marvelous little book is that its author has made the arduous task of hoping a little bit easier for the struggling Christian.

Edward T. Oakes, S.J.

University of St. Mary of the Lake

Mundelein, Illinois

Sixth Sunday of Easter, 2007

Related IgnatiusInsight.com Articles and Book Excerpts:

• Introduction to Abbot Vonier's The Human Soul | by Ralph McInerny

• Abbot Vonier and the Christian Sacrifice | Introduction to Abbot Vonier's A Key to the Doctrine of the Eucharist | Aidan Nichols, O.P.

• The Question of Hope | Peter Kreeft

• The Encyclical on Hope: On the "De-immanentizing" of the Christian Eschaton | Fr. James V. Schall, S.J.

• Life: Political, Endless, and Eternal | Fr. James V. Schall, S.J.

Abbot Vonier was a Benedictine monk who lived from 1876 to 1938. He was elected Abbot of Buckfast Abbey, England, in 1906, and served in that capacity until his death. During his lifetime Vonier gained fame as the rebuilder of Buckfast, which had been left in ruins following the Reformation, and as the author of some 15 books of popular theology--works which developed :a vast company of admirers who welcomed every new book of his with enthusiasm." A bestselling author in England of the 1920s--that golden age of Catholic letters when Chesterton, Knox and Belloc flourished--Abbot Vonier was a gifted intellectual who regarded his literary activity as part of the mission with which Divine Providence had charged him. His great desire, and achievement, was to instruct in the Catholic Faith, to reveal its glories as available here and now to every Christian.

December 15, 2011

"Loving the truth isn't the same thing...

... as arguing about it; when we argue, we are so bent on getting the other person to see our point of view that we hardly mind whether it is true or not; we become advocates. Loving the truth isn't the same thing as preaching it or writing about it; when we preach it or write about it we are too much concerned with making it clear, with getting it across, to appreciate it in its own nature.

Loving the truth isn't even the same thing as studying it, or meditating about it; when we study it, we are out to master it; when we meditate about it, we are using it as a lever which will help us to get a move on with the business of our own souls. No, we have got to love the truth with a jealous, consuming love that can't rest satisfied until it has won the allegiance of every sane man and woman on God's earth. And we don't, very often, love it like that.

We are God's spoiled children; his truth drops into your lap like a ripe fruit—Open thy mouth wide, he says, and I will fill it. There is a sense, you know, in which the false thinkers of today love the truth better than Christians do. Their fancied truth is something they have earned by their own labours, and they appreciate it more than we appreciate the real truth which has dropped into our laps.

The truth of which we are speaking is not a set of abstract propositions, however august. We are to love the truth as it is in Christ; he himself is truth incarnate, and we call upon every human mind to surrender to his service—every human every human mind, and our own minds first; but it must be a real intellectual surrender.

We are to preach the gospel, not as a mere recipe which we have tried and found useful, not as a mere pattern of living which we have learned to admire, but as truth, which has a right to be told, which would still have to be told, even if no heaven beckoned from above, no hell yawned beneath us. If we really loved the truth, then perhaps it would bite deeper into our minds, become realized and operative, not a mere set of formulas, which we accept with a shrug of the shoulders. And then perhaps we should recapture that spirit of faith, in which the men who went before us moved the world.

— Monsignor Ronald Knox (Ignatius Insight author page), from the chapter, "The Spirit of Faith", from A Retreat for Lay People: Spiritual Guidance for Christian Living (also available in electronic book format).

When Seconds Count

When Seconds Count | Daniel Allott | Catholic World Report

A look at what happens when parents continue a pregnancy after a fatal diagnosis

Maria Keller was pregnant with her fourth child when she visited her doctor for a routine ultrasound at 20 weeks and was confronted with a moment all mothers dread.

Maria and her husband, Joe, suspected something was not quite right when the ultrasound technician suddenly became quiet as she caught the first glimpses of the couple's unborn child on the ultrasound screen.

Then the technician abruptly exited the room, leaving Joe and Maria waiting for a few tense minutes before they were called in to see the doctor, who met them with a distressed look on his face.

The ultrasound had revealed that their son, who would later be named James Nicholas, had osteogenesis imperfecta type II, a genetic bone disorder that causes collagen deficiency and defective connective tissue. Most babies diagnosed with OI Type II die within the first year of life of respiratory failure.

"We were frankly told that we shouldn't expect James Nicholas to survive birth, and that if he did survive to prepare for it to be a matter of seconds or maybe a couple of minutes, if we were blessed," Joe told CWR in an interview.

Until recently, it was not uncommon for delivery room doctors to seize babies with lethal anomalies immediately after birth. The belief was that it would be less traumatic for parents not to hold or even see babies who would likely die soon after birth.

Today there is better recognition that deep maternal-fetal bonding can take place. But a strong anti-life bias persists against unborn and newborn babies with fatal conditions. There is broad public support for abortion of unborn children with profound disabilities.

December 14, 2011

"Indeed, it is theism, not naturalism, that deserves to be called 'the scientific worldview.'"

The New York Times breaks the shocking news that there are philosophers who—steady yourself!—believe in the existence of God. (What would Aristotle, St. Augustine of Hippo, St. Thomas Aquinas, or Etienne Gilson—to name just a very few—think of such insanity?) From the piece, "Philosopher Sticks Up for God", which is about the highly regarded philosopher, Alvin Plantinga, a Protestant (Calvinist) who is emeritus John A. O'Brien Professor of Philosophy at the University of Notre Dame:

For too long, Mr. Plantinga contends in a new book, theists have been on the defensive, merely rebutting the charge that their beliefs are irrational. It's time for believers in the old-fashioned creator God of the Bible to go on the offensive, he argues, and he has some sports metaphors at the ready. (Not for nothing did he spend two decades at Notre Dame.)

In "Where the Conflict Really Lies: Science, Religion and Naturalism," published last week by Oxford University Press, he unleashes a blitz of densely reasoned argument against "the touchdown twins of current academic atheism," the zoologist Richard Dawkins and the philosopher Daniel C. Dennett, spiced up with some trash talk of his own.

Mr. Dawkins? "Dancing on the lunatic fringe," Mr. Plantinga declares. Mr. Dennett? A reverse fundamentalist who proceeds by "inane ridicule and burlesque" rather than by careful philosophical argument.

On the telephone Mr. Plantinga was milder in tone but no less direct. "It seems to me that many naturalists, people who are super-atheists, try to co-opt science and say it supports naturalism," he said. "I think it's a complete mistake and ought to be pointed out."

The so-called New Atheists may claim the mantle of reason, not to mention a much wider audience, thanks to best sellers like Mr. Dawkins's fire-breathing polemic, "The God Delusion." But while Mr. Plantinga may favor the highly abstruse style of analytic philosophy, to him the truth of the matter is crystal clear.

Theism, with its vision of an orderly universe superintended by a God who created rational-minded creatures in his own image, "is vastly more hospitable to science than naturalism," with its random process of natural selection, he writes. "Indeed, it is theism, not naturalism, that deserves to be called 'the scientific worldview.' "

Exactly right, as this blog has said in one way or another more than a few times. The really honest adherent of pure naturalism will ultimately have to doubt both the basis for his studies and the reasons for pursuing them. But the disciples of naturalism tend to hedge their bets, and many would rather focus on loudly attacking theism than staring into the deep abyss created by their own empty philosophical premises.

Related on Ignatius Insight:

Carl E. Olson's Blog

- Carl E. Olson's profile

- 20 followers