Carl E. Olson's Blog, page 253

December 26, 2011

"The real dirty little secret of religiosity in America...

... is that there are so many people for whom spiritual interest, thinking about ultimate questions, is minimal," says Mark Silk, professor of religion and public life at Trinity College, Hartford, Conn.

That is from this USA Today article about the "'So What?' set":

Researchers have begun asking the kind of nuanced questions that reveal just how big the So What set might be:

•44% told the 2011 Baylor University Religion Survey they spend no time seeking "eternal wisdom," and 19% said "it's useless to search for meaning."

•46% told a 2011 survey by Nashville-based evangelical research agency, LifeWay Research, they never wonder whether they will go to heaven.

•28% told LifeWay "it's not a major priority in my life to find my deeper purpose." And 18% scoffed that God has a purpose or plan for everyone.

•6.3% of Americans turned up on Pew Forum's 2007 Religious Landscape Survey as totally secular — unconnected to God or a higher power or any religious identity and willing to say religion is not important in their lives.

Hemant Mehta, who blogs as The Friendly Atheist, calls them the "apatheists"

It's a clever and apt name, as indicated by these quotes:

Helton, a high school band teacher in Chicago, only goes to the Catholic Church of his youth to hear his mother sing in the choir.

His mind led him away. The more Helton read evolutionary psychology and neuro-psychology, he says, the more it seemed to him, "We might as well be cars. That, to me, makes more sense than believing what you can't see."

Ashley Gerst, 27, a 3-D animator and filmmaker in New York, shifts between "leaning to the atheist and leaning toward apathy."

"I would just like to see more people admit they don't believe. The only thing I'm pushy about is I don't want to be pushed. I don't want to change others and I don't want to debate my view," Gerst says.

Most So Whats are like Gerst, says David Kinnaman, author of You Lost Me on young adults drifting away from church.

They're uninterested in trying to talk a diverse set of friends into a shared viewpoint in a culture that celebrates an idea that all truths are equally valid, he says. Personal experience, personal authority matter most. Hence Scripture and tradition are quaint, irrelevant, artifacts. Instead of followers of Jesus, they're followers of 5,000 unseen "friends" on Facebook or Twitter.

My own introduction to this general mentality came about twenty years, when my girlfriend (now my wife) was working on a project for a class on evangelization at Multnomah Bible College. It involved asking three non-Christians a series of questions about life, death, and a few other light-weight topics. One of the questions was, "What do you think is the meaning of life?" I was with her when she asked the questions of a relative of mine, a forty-year-old man with a Masters degree in education who taught at the local high school. He paused for a few moments, with a blank expression on his face, and then said, with remarkable honesty, "That's a really good question; I've never thought about it before."

I think I've mentioned that response more than once on this blog, if only because it shocked me and it showed me there are, in fact, many people who go through life without asking the Big Questions or even knowing of their existence. It still surprises me a bit, but of course I've seen and heard much more over the years along the same lines.

It brings to mind another conversation I had a number of years ago, with a longtime family friend (a Catholic!), who used to babysit me when I was very young and whose husband, a doctor, was something of a cultural and intellectual mentor when I was growing up (we talked often, for example, about Mozart, T. S. Eliot, and Frederic Remington, and he introduced me a lot of great music and literature). She said, "I remember that when you were three or four, you would often sit on the sidewalk in front of your house and simply stare into the distance for long periods of time." And then, with a laugh, she said, "I wondered for a while if you were mentally handicapped" (well, hey, who hasn't wondered that?!). I told her that I remembered sitting there, usually in the morning summer sunlight, and that I had been thinking. "Thinking about what?", she asked. "God and eternity", I said, "I was fascinated by the notion of eternity, and I was equally fascinated by the idea that God is eternal. So I would sit and mull it over." She thought I was joking (as I usually am joking), but I assured her that I was telling the truth.

Granted, I didn't make any breakthroughs or chart new theological territories sitting on the sidewalk as a young boy. But the point is not about intellectual abilities or acheivements, but about the basic questions of human existence. From a very young age I wondered: What is this life about? Why am I here? What does it mean to exist? Why do I exist? And while I certainly took comfort in the answers given by my Christian parents, I often pushed and poked at those answers as well. I took it for granted that people, at the end of the day, had the same questions.

This is why, I'm sure, that authors such as Chesterton and Walker Percy—two very different personalities with quite different approaches—resonated with me upon first read. They both came from agnostic backgrounds and went through times of spiritual darkness in their youth, but emerged as men of faith and champions of reason who believed the proper response to existence is not apathy and despair, but wonder and gratitude. And what you find with both men—just as you find with Augustine and Aquinas and Newman and so forth—is a profound humility before the mystery of life and the Mystery of God. And that humility is coupled with doctrine, dogma, and devotion, precisely because the authentic and mature pursuit of meaning does not involve dallying with vague mutterings about "being spiritual" and "being good" without really considering what is means to be spiritual, to be good, and to be a creature made in the image and likeness of God. "I would maintain", wrote Chesterton, "that thanks are the highest form of thought; and that gratitude is happiness doubled by wonder."

Chesterton also wrote that when we talk about "modern thought", we tend to forget "the familiar fact that moderns do not think. They only feel..." What the USA Today piece describes as apathy is indeed a form of sloth, or acedia, but it is also a clear type of emotive cowardice. Men who refuse to ask, "What is man?", are not really men, but are, in the words of Eliot, hollow, stuffed men, leaning together, headpiece filled with straw:

Shape without form, shade without colour,

Paralysed force, gesture without motion; ...

In this last of meeting places

We grope together

And avoid speech

Gathered on this beach of the tumid river

The beach of our age is attractive enough, formed by a million glittering grains of technological gadgets and devices, hi-tech trinkets and data-crunching baubles. The waters of this tumid river consist of instant, streaming information; our civilization has not only mastered the art of distraction, it has made it the ultimate art form of meaning, and nearly everything touted as necessary and current is meant to distract our mind, deflect our gaze, and define our soul. The meaning of life is now, increasingly, said to be that life has no meaning since "meaning" is not meaningful. The questions that guide our days are practical and of no eternal significane: "Shall I part my hair behind? Do I dare to eat a peach?" We have become a society of Prufocks.

This is a further, sad sign of what Percy called "an ontological impoverishment". Percy believed that art and literature were means of responding to this malnourishment of mind and soul. The contemporary novelist, he wrote in the essay "Diagnosing the Modern Malaise", "must be an epistemologist of sorts. He must know how to send messages and decipher them." Therein also lies the great challenge for everyone who believes that Truth exists and can be known: send messages and decipher. After all, isn't that what God, the Artist par excellence, did when he sent the Son, the Eternal Word, into the world? What greater message is there than the Incarnation, who has deciphered the human condition by becoming man and dwelling among us?

Christ is born! Glorify Him!

Fr. Groeschel on the martyrdom of St. Stephen and devotion to Christ

From the Introduction to Fr. Benedict Groeschel's impressive study, I Am With You Always: A Study of the History and Meaning of Personal Devotion to Jesus Christ for Catholic, Orthodox and Protestant Christians:

When looking for a descriptive definition of Christian devotion, I turned to the account of the first recorded prayer to the ascended Christ—the words of St. Stephen at his martyrdom (Acts 7:55-60). First, the martyr sees the heavens open and the Son of Man standing at the right hand of God. As he  is being stoned to death, he prays two distinct prayers: one asks that the Lord Jesus receive his spirit, and the other is a request that the Lord will forgive his enemies. These are clearly prayers to Jesus the Lord. Later we will explore the full significance of this type of invocation, especially in the Pauline writings.

is being stoned to death, he prays two distinct prayers: one asks that the Lord Jesus receive his spirit, and the other is a request that the Lord will forgive his enemies. These are clearly prayers to Jesus the Lord. Later we will explore the full significance of this type of invocation, especially in the Pauline writings.

After an analysis ofmany devotional prayers and some personal introspection, I think that a good descriptive definition of devotion to Christ will have the following elements.

1. A powerful psychological awareness of the personal presence of Christ, or a very strong desire for that presence.

2. An immediate appeal to Christ about personally significant things in one's life. This makes devotion a "real relationship" and not simply a meditation. The personally significant thing may be an imperative need ("Lord, receive my spirit") or a strong desire ("Lord, that I may see") or a fear ("Lord, save me lest I perish"). It may be a spiritual need ("Increase my faith"), or the need of someone dear to us ("Lord, have pity on my son"). It may be simply a desire to be silent in Christ's presence ("Come aside and rest awhile"). We must relate to Christ not only with our minds but with our hearts.

3. We must be willing to do what He asks. This is interesting in Stephen's case. Not long before, Christ had given the command: "Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you" (Mt 5:44). To people of that time such an injunction did not make sense. It had to be accepted on faith. With Stephen, we see a follower of Christ fulfilling this command for the first time in the most dramatic circumstances. Stephen does what Jesus asks, although he may not really have understood why he had to love his enemies. I am not sure that we understand it well even now.

4. Stephen did not fail, but we often do. Some of the psalms (Psalm 51, for example) are beautiful prayers of repentance, and we see repentance in the New Testament—that of St. Peter, for instance—following the failure to be loyal to Christ. Repentance is always part of Christian devotion.

5. Devotion must include trust in Christ. Christ often rebukes the disciples for their little faith, in the sense of trust in Him. He also praised the faith of those who did trust in Him. Faith in the Gospel is always immediate, personal, and includes the idea of trust. Trusting himself to Christ in the hour of death, Stephen makes a clear statement of his belief in life after death; "Lord Jesus, receive my spirit" (Acts 7:59).

Not only does Stephen trust, but he petitions: "Receive my spirit." In most cases devotion includes a prayer for God's merciful providence to grant some favor or grace. The centurion asking for the healing of his boy (servant or son) does so with a confidence that impresses even Jesus (Mt 8:5-11).

6. Finally, mature Christian devotion has a kind of simple eschatological element to it, in which the devout person is thinking not necessarily of the end of the ages, but of his own mortality. The devout are sustained by the hope that at the time of death, they will "see" the face of Christ in a new way, that He awaits them.

To summarize this definition, we can define Christian devotion as a powerful awareness of or longing for Christ's presence, accompanied by a trustful surrender to Him of our personal needs. To this is joined a willingness to do His will and a sense of repentance for any previous failure to do so. We must trust Him not only with our present need but also with the salvation of our souls and those we care about. Finally, in some way we must anticipate our meeting with Him at the hour of death.

Read the entire Introduction. And here are the readings for today's feast of Saint Stephen, Protomartyr.

December 24, 2011

Pope: Christmas is an epiphany, not a matter of sentimentality or a commercial celebration

From Pope Benedict XVI's homily at Midnight Mass on the Solemnity of the Nativity of the Lord:

God has appeared – as a child. It is in this guise that he pits himself against all violence and brings a message that is peace. At this hour, when the world is continually threatened by violence in so many places and in so many different ways, when over and over again there are oppressors' rods and bloodstained cloaks, we cry out to the Lord: O mighty God, you have appeared as a child and you have revealed yourself to us as the One who loves us, the One through whom love will triumph. And you have shown us that we must be peacemakers with you. We love your childish estate, your powerlessness, but we suffer from the continuing presence of violence in the world, and so we also ask you: manifest your power, O God. In this time of ours, in this world of ours, cause the oppressors' rods, the cloaks rolled in blood and the footgear of battle to be burned, so that your peace may triumph in this world of ours.

Christmas is an epiphany – the appearing of God and of his great light in a child that is born for us. Born in a stable in Bethlehem, not in the palaces of kings. In 1223, when Saint Francis of Assisi celebrated Christmas in Greccio with an ox and an ass and a manger full of hay, a new dimension of the mystery of Christmas came to light. Saint Francis of Assisi called Christmas "the feast of feasts" – above all other feasts – and he celebrated it with "unutterable devotion" (2 Celano 199; Fonti Francescane, 787). He kissed images of the Christ-child with great devotion and he stammered tender words such as children say, so Thomas of Celano tells us (ibid.). For the early Church, the feast of feasts was Easter: in the Resurrection Christ had flung open the doors of death and in so doing had radically changed the world: he had made a place for man in God himself. Now, Francis neither changed nor intended to change this objective order of precedence among the feasts, the inner structure of the faith centred on the Paschal Mystery. And yet through him and the character of his faith, something new took place: Francis discovered Jesus' humanity in an entirely new depth. This human existence of God became most visible to him at the moment when God's Son, born of the Virgin Mary, was wrapped in swaddling clothes and laid in a manger. The Resurrection presupposes the Incarnation. For God's Son to take the form of a child, a truly human child, made a profound impression on the heart of the Saint of Assisi, transforming faith into love. "The kindness and love of God our Saviour for mankind were revealed" – this phrase of Saint Paul now acquired an entirely new depth. In the child born in the stable at Bethlehem, we can as it were touch and caress God. And so the liturgical year acquired a second focus in a feast that is above all a feast of the heart.

This has nothing to do with sentimentality. It is right here, in this new experience of the reality of Jesus' humanity that the great mystery of faith is revealed. Francis loved the child Jesus, because for him it was in this childish estate that God's humility shone forth. God became poor. His Son was born in the poverty of the stable. In the child Jesus, God made himself dependent, in need of human love, he put himself in the position of asking for human love – our love. Today Christmas has become a commercial celebration, whose bright lights hide the mystery of God's humility, which in turn calls us to humility and simplicity. Let us ask the Lord to help us see through the superficial glitter of this season, and to discover behind it the child in the stable in Bethlehem, so as to find true joy and true light.

Read the entire homily on the Vatican site.

"What, really, is the point of Christmas? Why did God become man?"

... The Catechism of the Catholic Church, in a section titled, "Why did the Word become flesh?" (pars 456-460) provides several complimentary answers: to save us, to show us God's love, and to be a model of holiness. And then, in what I think must be, for many readers, the most surprising and puzzling paragraph in the entire Catechism, there is this:

The Word became flesh to make us "partakers of the divine nature": "For this is why the Word became man, and the Son of God became the Son of man: so that man, by entering into communion with the Word and thus receiving divine sonship, might become a son of God." "For the Son of God became man so that we might become God." "The only-begotten Son of God, wanting to make us sharers in his divinity, assumed our nature, so that he, made man, might make men gods." (par 460)

So that "we might become God"? Surely, a few might think, this is some sort of pantheistic slip of the theological pen, or perhaps a case of good-intentioned but poorly expressed hyperbole. But, of course, it is not. First, whatever problems there might have been in translating the Catechism into English, they had nothing to do with this paragraph. Secondly, the first sentence is from 2 Peter 1:4, and the three subsequent quotes are from, respectively, St. Irenaeus, St. Athanasius, and (gasp!) St. Thomas Aquinas. Finally, there is also the fact that this language of divine sonship—or theosis, also known as deification—is found through the entire Catechism. A couple more representative examples:

Justification consists in both victory over the death caused by sin and a new participation in grace. It brings about filial adoption so that men become Christ's brethren, as Jesus himself called his disciples after his Resurrection: "Go and tell my brethren." We are brethren not by nature, but by the gift of grace, because that adoptive filiation gains us a real share in the life of the only Son, which was fully revealed in his Resurrection. (par 654)

Our justification comes from the grace of God. Grace is favor, the free and undeserved help that God gives us to respond to his call to become children of God, adoptive sons, partakers of the divine nature and of eternal life. (par 1996)

Filial adoption, in making us partakers by grace in the divine nature, can bestow true merit on us as a result of God's gratuitous justice. This is our right by grace, the full right of love, making us "co-heirs" with Christ and worthy of obtaining "the promised inheritance of eternal life." The merits of our good works are gifts of the divine goodness. "Grace has gone before us; now we are given what is due.... Our merits are God's gifts." (par 2009)

The very first paragraph of the Catechism, in fact, asserts that God sent his Son so that in him "and through him, he invites men to become, in the Holy Spirit, his adopted children and thus heirs of his blessed life." God did not become man, in other words, to just be our friend, but so that we could truly and really, by grace, become members of his family, the Church. Christmas is the celebration of God becoming man, but it is also the proclamation that man is now able to be filled with and to share in God's own Trinitarian life.

That's the opening of my 2008 essay, "Theosis: The Reason for the Season". Read the entire essay on Ignatius Insight:

"The God in the Cave": G.K. Chesterton on the birth of Jesus Christ

"The God In The Cave" | G. K. Chesterton | From The Everlasting Man

This sketch of the human story began in a cave; the cave which popular science associates with the cave-man and in which practical discovery has really found archaic drawings of animals. The second half of human history, which was like a new creation of the world, also begins in a cave. There is even a shadow of such a fancy in the fact that animals were again present; for it was a cave used as a stable by the mountaineers of the uplands about Bethlehem; who still drive their cattle into such holes and caverns at night.

It was here that a homeless couple had crept underground with the cattle when the doors of the crowded caravanserai had been shut in their faces; and it was here beneath the very feet of the passersby, in a cellar under the very floor of the world, that Jesus Christ was born. But in that second creation there was indeed something symbolical in the roots of the primeval rock or the horns of the prehistoric herd. God also was a "Cave Man", and, had also traced strange shapes of creatures, curiously colored upon the wall of the world; but the pictures that he made had come to life.

caravanserai had been shut in their faces; and it was here beneath the very feet of the passersby, in a cellar under the very floor of the world, that Jesus Christ was born. But in that second creation there was indeed something symbolical in the roots of the primeval rock or the horns of the prehistoric herd. God also was a "Cave Man", and, had also traced strange shapes of creatures, curiously colored upon the wall of the world; but the pictures that he made had come to life.

A mass of legend and literature, which increases and will never end has repeated and rung the changes on that single paradox; that the hands that had made the sun and stars were too small to reach the huge heads of the cattle. Upon this paradox, we might almost say upon this jest, all the literature of our faith is founded. It is at least like a jest in this; that it is something which the scientific critic cannot see. He laboriously explains the difficulty which we have always defiantly and almost derisively exaggerated; and mildly condemns as improbable something that we have almost madly exalted as incredible; as something that would be much too good to be true, except that it is true. When that contrast between the cosmic creation and the little local infancy has been repeated, reiterated, underlined, emphasized, exulted in, sung, shouted, roared, not to say howled, in a hundred thousand hymns, carols, rhymes, rituals, pictures, poems, and popular sermons, it may be suggested that we hardly need a higher critic to draw our attention to something a little odd about it; especially one of the sort that seems to take a long time to see a joke, even his own joke.

But about this contrast and combination of ideas one thing may be said here, because it is relevant to the whole thesis of this little book. The sort of modern critic of whom I speak is generally much impressed with the importance of education in life and the importance of psychology in education. That sort of man is never tired of telling us that first impressions fix character by the law of causation; and he will become quite nervous if a child's visual sense is poisoned by the wrong colors on a golliwog or his nervous system prematurely shaken by a cacophonous rattle. Yet he will think us very narrow-minded, if we say that this is exactly why there really is a difference between being brought up as a Christian and being brought up as a Jew or a Moslem or an atheist.

The difference is that every Catholic child has learned from pictures, and even every Protestant child from stones, this incredible combination of contrasted ideas as one of the very first impressions on his mind. It is not merely a theological difference. It is a psychological difference which can outlast any theologies. It really is, as that sort of scientist loves to say about anything, incurable. Any agnostic or atheist whose childhood has known a real Christmas has ever afterwards, whether be likes it or not, an association in his mind between two ideas that most of mankind must regard as remote from each other; the idea of a baby and the idea of unknown strength that sustains the stars. His instincts and imagination can still connect them, when his reason can no longer see the need of the connection; for him there will always be some savor of religion about the mere picture of a mother and a baby; some hint of mercy and softening about the mere mention of the dreadful name of God. But the two ideas are not naturally or necessarily combined. They would not be necessarily combined for an ancient Greek or a Chinaman, even for Aristotle or Confucius. It is no more inevitable to connect God with an infant than to connect gravitation with a kitten. It has been created in our minds by Christmas because we are Christians; because we are psychological Christians even when we are not theological ones. In other words, this combination of ideas has emphatically, in the much disputed phrase, altered human nature.

There is really a difference between the man who knows it and the man who does not. It may not be a difference of moral worth, for the Moslem or the Jew might be worthier according to his lights; but it is a plain fact about the crossing of two particular lights, the conjunction of two stars in our particular horoscope. Omnipotence and impotence, or divinity and infancy, do definitely make a sort of epigram which a million repetitions cannot turn into a platitude. It is not unreasonable to call it unique.

Bethlehem is emphatically a place where extremes meet. Here begins, it is needless to say, another mighty influence for the humanization of Christendom. If the world wanted what is called a non-controversial aspect of Christianity, it would probably select Christmas. Yet it is obviously bound up with what is supposed to be a controversial aspect (I could never at any stage of my opinions imagine why); the respect paid to the Blessed Virgin. When I was a boy, a more Puritan generation objected to a statue upon my parish church representing the Virgin and Child. After much controversy, they compromised by taking away the Child. One would think that this was even more corrupted with Mariolatry, unless the mother was counted less dangerous when deprived of a sort of weapon. But the practical difficulty is also a parable.

You cannot chip away the statue of a mother from all round that of a newborn child. You cannot suspend the new-born child in mid-air; indeed, you cannot really have a statue of a newborn child at all. Similarly, you cannot suspend the idea of a newborn child in the void or think of him without thinking of his mother. You cannot visit the child without visiting the mother; you cannot in common human life approach the child except through the mother. If we are to think of Christ in this aspect at all, the other idea follows it as it is followed in history. We must either leave Christ out of Christmas, or Christmas out of Christ, or we must admit, if only as we admit it in an old picture, that those holy heads are too near together for the haloes not to mingle and cross.

It might be suggested, in a somewhat violent image, that nothing had happened in that fold or crack in the great gray hills except that the whole universe had been turned inside out. I mean that all the eyes of wonder and worship which had been turned outwards to the largest thing were now turned inward to the smallest. The very image will suggest all that multitudinous marvel of converging eyes that makes so much of the colored Catholic imagery like a peacock's tail. But it is true in a sense that God who had been only a circumference was seen as a centre; and a centre is infinitely small. It is true that the spiritual spiral henceforward works inwards instead of outwards, and in that sense is centripetal and not centrifugal. The faith becomes, in more ways than one, a religion of little things.

***

Traditions in art and literature and popular fable have quite sufficiently attested, as has been said, this particular paradox of the divine being in the cradle. Perhaps they have not so clearly emphasized the significance of the divine being in the cave. Curiously enough, indeed, tradition has not very clearly emphasized the cave. It is a familiar fact that the Bethlehem scene has been represented in every possible setting of time and country, of landscape and architecture; and it is a wholly happy and admirable fact that men have conceived it as quite different according to their different individual traditions and tastes. But while all have realized that it was a stable, not so many have realized that it was a cave. Some critics have even been so silly as to suppose that there was some contradiction between the stable and the cave; in which case they cannot know much about caves or stables in Palestine. As they see differences that are not there it is needless to add that they do not see differences that are there. When a well-known critic says, for instance, that Christ being born in a rocky cavern is like Mithras having sprung alive out of a rock, it sounds like a parody upon comparative religion. There is such a thing as the point of a story, even if it is a story in the sense of a lie. And the notion of a hero appearing, like Pallas from the brain of Zeus, mature and without a mother, is obviously the very opposite of the idea of a god being born like an ordinary baby and entirely dependent on a mother. Whichever ideal we might prefer, we should surely see that they are contrary ideals. It is as stupid to connect them because they both contain a substance called stone as to identify the punishment of the Deluge with the baptism in the Jordan because they both contain a substance called water.

Whether as a myth or a mystery, Christ was obviously conceived as born in a hole in the rocks primarily because it marked the position of one outcast and homeless . . . .

It would be vain to attempt to say anything adequate, or anything new, about the change which this conception of a deity born like an outcast or even an outlaw had upon the whole conception of law and its duties to the poor and outcast. It is profoundly true to say that after that moment there could be no slaves. There could be and were people bearing that legal title, until the Church was strong enough to weed them out, but there could be no more of the pagan repose in the mere advantage to the state of keeping it a servile state. Individuals became important, in a sense in which no instruments can be important. A man could not be a means to an end, at any rate to any other man's end. All this popular and fraternal element in the story has been rightly attached by tradition to the episode of the Shepherds, who found themselves talking face to face with the princes of heaven. But there is another aspect of the popular element as represented by the shepherds which has not perhaps been so fully developed; and which is more directly relevant here.

Men of the people, like the shepherds, men of the popular tradition, had everywhere been the makers of the mythologies. It was they who had felt most directly, with least check or chill from philosophy or the corrupt cults of civilization, the need we have already considered; the images that were adventures of the imagination; the mythology that was a sort of search; the tempting and tantalizing hints of something half-human in nature; the dumb significance of seasons and special places. They had best understood that the soul of a landscape is a story, and the soul of a story is a personality. But rationalism had already begun to rot away these really irrational though imaginative treasures of the peasant; even as a systematic slavery had eaten the peasant out of house and home. Upon all such peasantries, everywhere there was descending a dusk and twilight of disappointment, in the hour when these few men discovered what they sought. Everywhere else, Arcadia was fading from the forest. Pan was dead and the shepherds were scattered like sheep. And though no man knew it, the hour was near which was to end and to fulfill all things; and, though no man heard it, there was one far-off cry in an unknown tongue upon the heaving wilderness of the mountains. The shepherds had found their Shepherd.

And the thing they found was of a kind with the things they sought. The populace had been wrong in many things; but they had not been wrong in believing that holy things could have a habitation and that divinity need not disdain the limits of time and space. And the barbarian who conceived the crudest fancy about the sun being stolen and hidden in a box, or the wildest myth about the god being rescued and his enemy deceived with a stone, was nearer to the secret of the cave and knew more about the crisis of the world, than all those in the circle of cities round the Mediterranean who had become content with cold abstractions or cosmopolitan generalizations; than all those who were spinning thinner and thinner threads of thought out of the transcendentalism of Plato or the orientalism of Pythagoras. The place that the shepherds found was not an academy or an abstract republic; it was not a place of myths allegorized or dissected or explained or explained away. It was a place of dreams come true. Since that hour, no mythologies have been made in the world. Mythology is a search. . . . .

The philosophers had also heard. It is still a strange story, though an old one, how they came out of orient lands, crowned with the majesty of kings and clothed with something of the mystery of magicians. That truth that is tradition has wisely remembered them almost as unknown quantities, as mysterious as their mysterious and melodious names; Melchior, Caspar, Balthazar. But there came with them all that world of wisdom that had watched the stars in Chaldea and the sun in Persia; and we shall not be wrong if we see in them the same curiosity that moves all the sages. They would stand for the same human ideal if their names had really been Confucius or Pythagoras or Plato. They were those who sought not tales but the truth of things; and since their thirst for truth was itself a thirst for God, they also have had their reward. But even in order to understand that reward, we must understand that for philosophy as much as mythology, that reward was the completion of the incomplete.

Such learned men would doubtless have come, as these learned men did come, to find themselves confirmed in much that was true in their own traditions and right in their own reasoning. Confucius would have found anew foundation for the family in the very reversal of the Holy Family; Buddha would have looked upon a new renunciation, of stars rather than jewels and divinity than royalty. These learned men would still have the right to say, or rather a new right to say, that there was truth in their old teaching. But after all these learned men would have come to learn. They would have come to complete their conceptions with something they had not yet conceived; even to balance their imperfect universe with something they might once have contradicted. Buddha would have come from his impersonal paradise to worship a person. Confucius would have come from his temples of ancestor-worship to worship a child. . . . .

The Magi, who stand for mysticism and philosophy, are truly conceived as seeking something new and even as finding something unexpected. That tense sense of crisis which still tingles in the Christmas story and even in every Christmas celebration, accentuates the idea of a search and a discovery. For the other mystical figures in the miracle play; for the angel and the mother, the shepherds and the soldiers of Herod, there may be aspects both simpler and more supernatural, more elemental or more emotional. But the Wise Men must be seeking wisdom; and for them there must be a light also in the intellect. And this is the light; that the Catholic creed is catholic and that nothing else is catholic. The philosophy of the Church is universal. The philosophy of the philosophers was not universal. Had Plato and Pythagoras and Aristotle stood for an instant in the light that came out of that little cave, they would have known that their own light was not universal. It is far from certain, indeed, that they did not know it already. Philosophy also, like mythology, had very much the air of a search. It is the realization of this truth that gives its traditional majesty and mystery to the figures of the Three Kings; the discovery that religion is broader than philosophy and that this is the broadest of religions, contained within this narrow space . . . .

We might well be content to say that mythology had come with the shepherds and philosophy with the philosophers; and that it only remained for them to combine in the recognition of religion. But there was a third element that must not be ignored and one which that religion for ever refuses to ignore, in any revel or reconciliation. There was present in the primary scenes of the drama that Enemy that had rotted the legend with lust and frozen the theories into atheism, but which answered the direct challenge with something of that more direct method which we have seen in the conscious cult of the demons. In the description of that demon-worship, of the devouring detestation of innocence shown in the works of its witchcraft and the most inhuman of its human sacrifice, I have said less of its indirect and secret penetration of the saner paganism; the soaking of mythological imagination with sex; the rise of imperial pride into insanity. But both the indirect and the direct influence make themselves felt in the drama of Bethlehem. A ruler under the Roman suzerainty, probably equipped and surrounded with the Roman ornament and order though himself of eastern blood, seems in that hour to have felt stirring within him the spirit of strange things.

We all know the story of how Herod, alarmed at some rumor of a mysterious rival, remembered the wild gesture of the capricious despots of Asia and ordered a massacre of suspects of the new generation of the populace. Everyone knows the story; but not everyone has perhaps noted its place in the story of the strange religions of men. Not everybody has seen the significance even of its very contrast with the Corinthian columns and Roman pavement of that conquered and superficially civilized world. Only, as the purpose in his dark spirit began to show and shine in the eyes of the Idumean, a seer might perhaps have seen something like a great grey ghost that looked over his shoulder; have seen behind him filling the dome of night and hovering for the last time over history, that vast and fearful fact that was Moloch of the Carthaginians; awaiting his last tribute from a ruler of the races of Shem. The demons, in that first festival of Christmas, feasted also in their own fashion.

***

Unless we understand the presence of that enemy, we shall not only miss the point of Christianity, but even miss the point of Christmas. Christmas for us in Christendom has become one thing, and in one sense even a simple thing. But like all the truths of that tradition, it is in another sense a very complex thing. Its unique note is the simultaneous striking of many notes; of humility, of gaiety, of gratitude, of mystical fear, but also of vigilance and of drama. It is not only an occasion for the peacemakers any more than for the merry makers; it is not only a Hindu peace conference any more than it is only a Scandinavian winter feast. There is something defiant in it also; something that makes the abrupt bells at midnight sound like the great guns of a battle that has just been won. All this indescribable thing that we call the Christmas atmosphere only bangs in the air as something like a lingering fragrance or fading vapor from the exultant, explosion of that one hour in the Judean hills nearly two thousand years ago. But the savor is still unmistakable, and it is something too subtle or too solitary to be covered by our use of the word peace. By the very nature of the story, the rejoicings in the cavern were rejoicings in a fortress or an outlaws den; properly understood it is not unduly flippant to say they were rejoicing in a dug-out.

It is not only true that such a subterranean chamber was a hiding-place from enemies; and that the enemies were already scouring the stony plain that lay above it like a sky. It is not only that the very horse-hoofs of Herod might in that sense have passed like thunder over the sunken head of Christ. It is also that there is in that image a true idea of an outpost, of a piercing through the rock and an entrance into an enemy territory. There is in this buried divinity an idea of undermining the world; of shaking the towers and palaces from below; even as Herod the great king felt that earthquake under him and swayed with his swaying palace.

That is perhaps the mightiest of the mysteries of the cave. It is already apparent that though men are said to have looked for hell under the earth, in this case it is rather heaven that is under the earth. And there follows in this strange story the idea of an upheaval of heaven. That is the paradox of the whole position; that henceforth the highest thing can only work from below. Royalty can only return to its own by a sort of rebellion. Indeed the Church from its beginnings, and perhaps especially in its beginnings, was not so much a principality as a revolution against the prince of the world. This sense that the world had been conquered by the great usurper, and was in his possession, has been much deplored or derided by those optimists who identify enlightenment with ease. But it was responsible for all that thrill of defiance and a beautiful danger that made the good news seem to be really both good and new. It was in truth against a huge unconscious usurpation that it raised a revolt, and originally so obscure a revolt. Olympus still occupied the sky like a motionless cloud molded into many mighty forms; philosophy still sat in the high places and even on the thrones of the kings, when Christ was born in the cave and Christianity in the catacombs.

In both cases, we may remark the same paradox of revolution; the sense of something despised and of something feared. The cave in one aspect is only a hole or corner into which the outcasts are swept like rubbish; yet in the other aspect it is a hiding-place of something valuable which the tyrants are seeking like treasure. In one sense they are there because the inn-keeper would not even remember them, and in another because the king can never forget them. We have already noted that this paradox appeared also in the treatment of the early Church. It was important while it was still insignificant, and certainly while it was still impotent. It was important solely because it was intolerable; and in that sense it is true to say that it was intolerable because it was intolerant. It was resented, because, in its own still and almost secret way, it had declared war. It had risen out of the ground to wreck the heaven and earth of heathenism. It did not try to destroy all that creation of gold and marble; but it contemplated a world without it. It dared to look right through it as though the gold and marble had been glass. Those who charged the Christians with burning down Rome with firebrands were slanderers; but they were at least far nearer to the nature of Christianity than those among the moderns who tell us that the Christians were a sort of ethical society, being martyred in a languid fashion for telling men they had a duty to their neighbors, and only mildly disliked because they were meek and mild.

Herod had his place, therefore, in the miracle play of Bethlehem because he is the menace to the Church Militant and shows it from the first as under persecution and fighting for its life. For those who think this a discord, it is a discord that sounds simultaneously with the Christmas bells. For those who think the idea of the Crusade is one that spoils the idea of the Cross, we can only say that for them the idea of the Cross is spoiled; the idea of the Cross is spoiled quite literally in the cradle. It is not here to the purpose to argue with them on the abstract ethics of fighting; the purpose in this place is merely to sum up the combination of ideas that make up the Christian and Catholic idea, and to note that all of them are already crystallized in the first Christmas story.

They are three distinct and commonly contrasted things which are nevertheless one thing; but this is the only thing which can make them one. The first is the human instinct for a heaven, that shall be as literal and almost as local as a home. It is the idea pursued by all poets and pagans making myths; that a particular place must be the shrine of the god or the abode of the blest; that fairyland is a land; or that the return of the ghost must be the resurrection of the body. I do not here reason about the refusal of rationalism to satisfy this need. I only say that if the rationalists refuse to satisfy it, the pagans: will not be satisfied. This is present in the story of Bethlehem and Jerusalem as it is present in the story of Delos and Delphi, and as it is not present in the whole universe of Lucretius or the whole universe of Herbert Spencer.

The second element is a philosophy larger than other philosophies; larger than that of Lucretius and infinitely larger than that of Herbert Spencer. It looks at the world through a hundred windows where the ancient stoic or the modem agnostic only looks through one. It sees life with thousands of eyes belonging to thousands of different sorts of people, where the other is only the individual standpoint of a stoic or an agnostic. It has something for all moods of man, it finds work for all kinds of men, it understands secrets of psychology, it is aware of depths of evil, it is able to distinguish between real and unreal marvels and miraculous exceptions, it trains itself in tact about hard cases, all with a multiplicity and subtlety and imagination about the varieties of life which is far beyond the bald or breezy platitudes of most ancient or modem moral philosophy. In a word, there is more in it; it finds more in existence to think about; it gets more out of life. Masses of this material about our many-sided life have been added since the time of St. Thomas Aquinas. But St. Thomas Aquinas alone would have found himself limited in the world of Confucius or of Comte.

And the third point is this; that while it is local enough for poetry and larger than any other philosophy, it is also a challenge and a fight. While it is deliberately broadened to embrace every aspect of truth, it is still stiffly embattled against every mode of error. It gets every kind of man to fight for it, it gets every kind of weapon to fight with, it widens its knowledge of the things that are fought for and against with every art of curiosity or sympathy; but it never forgets that it is fighting. It proclaims peace on earth and never forgets why there was war in heaven.

This is the trinity of truths symbolized here by the three types in the old Christmas story; the shepherds and the kings and that other king who warred upon the children. It is simply not true to say that other religions and philosophies are in this respect its rivals. It is not true to say that any one of them combines these characters; it is not true to say that any one of them pretends to combine them. Buddhism may profess to be equally mystical; it does not even profess to be equally military. Islam may profess to be equally military; it does not even profess to be equally metaphysical and subtle. Confucianism may profess to satisfy the need of the philosophers for order and reason; it does not even profess to satisfy the, need of the mystics for miracle and sacrament and the consecration of concrete things. There are many evidences of this presence of a spirit at once universal and unique.

One will serve here which is the symbol of the subject of this chapter; that no other story, no pagan legend or philosophical anecdote or historical event, does in fact affect any of us with that peculiar and even poignant impression produced on us by the word Bethlehem. No other birth of a god or childhood of a sage seems to us to be Christmas or anything like Christmas. It is either too cold or too frivolous, or too formal and classical, or too simple and savage, or too occult and complicated. Not one of us, whatever his opinions, would ever go to such a scene with the sense that he was going home. He might admire it because it was poetical, or because it was philosophical or any number of other things in separation; but not because it was itself. The truth is that there is a quite peculiar and individual character about the hold of this story on human nature; it is not in its psychological substance at all like a mere legend or the life of a great man. It does not exactly in the ordinary sense turn our minds to greatness; to those extensions and exaggerations of humanity which are turned into gods and heroes, even by the healthiest sort of hero worship. It does not exactly work outwards, adventurously to the wonders to be found at the ends of the earth.

It is rather something that surprises us from behind, from the hidden and personal part of our being; like that which can sometimes take us off our guard in the pathos of small objects or the blind pieties of the poor. It is rather as if a man had found an inner room in the very heart of his own house, which he had never suspected; and seen a light from within. It is if he found something at the back of his own heart that, betrayed him into good. It is not made of what the world would call strong materials; or rather, it is made of materials whose strength is in that winged levity with which they brush and pass. It is all that is in us but a brief tenderness that there made eternal; all that means no more than a momentary softening that is in some strange fashion become strengthening and a repose; it is the broken speech and the lost word that are made positive and suspended unbroken; as the strange kings fade into a far country and the mountains resound no more with the feet of the shepherds; and only the night and the cavern lie in fold upon fold over something more human than humanity.

G. K. Chesterton (1874-1936) Author Page | Ignatius Insight

• Articles By and About G. K. Chesterton

• Ignatius Press Books about G. K. Chesterton

• Books by G. K. Chesterton

What is the Nativity? | Fr. James V. Schall, S.J. on Christmas, 2011

A student of mine gave me a book for the end of a semester. She is Jewish but wanted to give me a Christmas card with it. She told me, "I looked but there are no 'Christmas Cards' in the shop, only 'Holiday Card.'" Her card said, "Seasons Greetings." It was decorated with shiny green leaves and an elegant red artificial flower. One has to be touched by the effort.

This comment about "Holiday Cards" made me take a second look at the cards I have already received. I tend to get actual "Christmas Cards." From Australia, I have a card with a green wreath on a door with "An IRISH Christmas Blessing for You and Yours." The blessing reads: "May your hearth be ever warm, your table ever full, your joys ever new, your love ever growing, and your memories ever lasting," followed by something which is probably "Merry Christmas" in Gaelic.

The President of Georgetown's Christmas card shows a lovely sketch of our elegant Gothic Healy Building from below the library steps. Off the steps, a lamp post with a green wreath and a red bow are seen.

Friends in Salinas, California, who visited me this year here in Georgetown, sent a lovely Madonna and Child card with the words "Peace on Earth."

Another friend in Virginia sent a very cute card with three identical little angels, each with hands folded, blond hair with halo. Two have eyes piously closed, but the last one has hers wide open, and we see her toes sticking out of from under her long gown.

Many cards have photos of some family scene, often before a Christmas tree, snow or festive dress. This sort of card keeps visual touch with growing and changing families.

From England, I have a card, a sketch on red paper showing a happy Joseph and Mary gazing at the child in a crib with the star behind and above them.

From my Catholic Indian friends, Maya and Peeya, I have a card with "Christ Is Born". Against a night scene, we see a hut and stable with Joseph and Mary. A light shines on the child. Behind we see a faint Crucifixion against the back wall. On the sides, a sheep and a donkey gaze into the scene.

From friends in Aptos, California, I have a very lovely scene with Mary sleeping and a very handsome Joseph holding the baby; again we are in a grotto while a donkey and a sheep look on from behind.

"From the widow of one of my cousins in Iowa, I have a card showing Joseph with a staff, leading a donkey on which Mary is sitting side-saddle. The star is behind them; they are still going to Bethlehem.

From Florida, I have a different version of the same scene, a much more tropical setting against a palm tree.

From England again, I have a lovely card of a stone Irish Cross sitting alone in a wintery scene, against a stone fence and gate. Reddish hills are seen in the background. The script is "Peace of the Season."

From Missouri, I have a card that shows a much-crowded scene in the inn-stable. The donkey is right on top of the crib looking in. The sheep is on the other side. The shepherds are there along with what looks like the three kings. Another donkey and sheep are at the side

My cousin in Detroit's card shows a very lovely winter scene, with snow falling on the pines. "A Christmas Wish—May God's peace surround you this Christmas and always." That is quite nice.

Finally, from Kentucky, we see a small church in the woods. There is a brook with a stone bridge over it. A horse pulls a man in a small sleigh towards the church. Snow is falling all around; heavy snow is already on the ground. Lights come through the church windows.

Christmas is not what we call a "holiday". Christmas is indeed a "holy" day, which is what the word "holiday" really means. It is not a good idea to pass through the Christmas season without reflecting on what it is. Catholicism is an intellectual religion, and the Feast of Christmas follows logically from the Annunciation, from the Incarnation. It points to the adolescence, to the public life of Christ; then as several cards depicted, to His Crucifixion. It is the same man who is "conceived by the Holy Spirit," who is "born" in Nazareth, during the reign of Caesar Augustus.

It is my view that the reason we do not see "Christmas cards" has to do with a deliberate choice, to a conscious choice that we "will" not know, that we "will" not allow anyone to think of what the Nativity of Christ might entail. Christmas cards do not disappear for no reason. In one sense, we can say that they disappear because there is no "demand"; it is a market thing. There is some truth to this. Today, if we buy a nice card and mail it, the cost is not insignificant. We can now email our greetings to Aunt Margaret for nothing; we can even access her living room and chat online.

Christmas is a public feast that, at its best, is wholly private. No one really knew the significance of the event in Bethlehem at the time it happened. God did not come into the world in power and drama. A few shepherds noticed, but even they had to be prodded by sounds and sights, by curiosity.

Soon the couple known as Joseph and Mary packed up and went home with the new baby who was not, evidently, born where He was by total accident, even if it looked that way. No sooner than they got there, they had to pack up again and be off to Egypt. It seems the king saw this Child as his potential rival. He even killed young boys who might be this child the Magi evidently told him about.

What is the Nativity? The Lord now actually appears. He is no longer in eternity, no longer in the womb of Mary. He is already a sign of contradiction. Many of the prophets of Israel longed to see what those shepherds saw and did not see it. Why did they not see? Was it because they were blind? They had eyes. But they did not want to see either. They had to lie to themselves lest they see.

What exactly happened here? The Child that was born was Christ the Lord. To explain Him, we need to talk accurately, to distinguish. If we get it wrong, we won't know. If we get it right, we will see a plan being worked out in the person, in the life and death of this Child now born in Bethlehem. Christmas cards, in fact, often do a good job of depicting what actually happened there in the stable, with the donkey and sheep, with the shepherds and Joseph and Mary.

Great things do not always happen in great ways, or at least, in ways we think are great. But great things did happen here, once and once only. It was not necessary for Christ to come more than once into this world, our world. His reality is still present. We seek to flee its import to us. We want every explanation but the one that explains.

Christmas is about the Word becoming flesh and dwelling amongst us. The Word is within the Godhead, in His active, eternal life. The Word seeks to lead us back to the purpose for which we are created, to share His eternal life. These things really happened. The world cannot pretend that it did not happen, though it has no alternative if it does not want to know the truth of who He was.

Christmas 2011 is in its very name. The "Mass" of Christmas, the Nativity of the Lord among us, the Word made flesh, the dwelling amongst us—these things we know and ponder. The song goes, "joy" to the world. Not joy for no reason. Joy because the Lord has come. We did not know He was coming. He came to dwell amongst us that we might eternally dwell with Him. There is no other reason, no other explanation of our being, of "why we are rather than are not."

We are now at an advanced status of our civilization wherein we have to say to our friends: "Pardon me, would you mind if I wished you a Merry Christmas." The only people who mind, I suspect, are those who are worried that what the Christians say about who is born in Bethlehem might be true. They prefer not to know. And that defines their souls.

Related Ignatius Insight Essays and Excerpts:

• Ox and Ass Know Their Lord | Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger

• What In Christmas Season Grows: On the Days Leading Up to the Nativity of the Lord | Fr. James V. Schall, S.J.

• Mary Immaculate | Fr. Kenneth Baker, S.J.

• Mary's Gift of Self Points the Way | Carl E. Olson

• Immaculate Mary, Matchless in Grace | John Saward

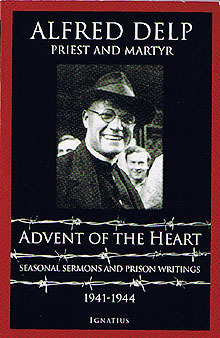

• The Mystery Made Present To Us | Fr. Alfred Delp, S.J.

• The Disciple Contemplates the Mother | Erasmo Leiva-Merikakis

• The Incarnation | Frank Sheed

• "Born of the Virgin Mary" | Paul Claudel

• The Old Testament and the Messianic Hope | Thomas Storck

• Christmas: Sign of Contradiction, Season of Redemption | Fr. James V. Schall, S.J.

• The God in the Cave | G.K. Chesterton

Fr. James V. Schall, S.J., is Professor of Political Philosophy at Georgetown University.

Fr. James V. Schall, S.J., is Professor of Political Philosophy at Georgetown University.

He is the author of numerous books on social issues, spirituality, culture, and literature including Another Sort of Learning, Idylls and Rambles, A Student's Guide to Liberal Learning, The Life of the Mind (ISI, 2006), The Sum Total of Human Happiness (St. Augustine's Press, 2007), The Regensburg Lecture (St. Augustine's Press, 2007), and The Mind That Is Catholic: Philosophical and Political Essays (CUA, 2008). His most recent book from Ignatius Press is The Order of Things(Ignatius Press, 2007).

His new book, The Modern Age, is available from St. Augustine's Press. Read more of his essays on his website.

December 23, 2011

"Josef Pieper, in his book on love, has shown ..."

... that man can only accept himself if he is accepted by another. He needs the other's presence, saying to him, with more than words: it is good that you exist. Only from the You can the I come into itself. Only if it is accepted, can it accept itself. Those who are unloved cannot even love themselves . This sense of being accepted comes in the first instance from other human beings. But all human acceptance is fragile. Ultimately we need a sense of being accepted unconditionally. Only if God accepts me, and I become convinced of this, do I know definitively: it is good that I exist. It is good to be a human being. If ever man's sense of being accepted and loved by God is lost, then there is no longer any answer to the question whether to be a human being is good at all. Doubt concerning human existence becomes more and more insurmountable. Where doubt over God becomes prevalent, then doubt over humanity follows inevitably. We see today how widely this doubt is spreading. We see it in the joylessness, in the inner sadness, that can be read on so many human faces today. Only faith gives me the conviction: it is good that I exist. It is good to be a human being, even in hard times. Faith makes one happy from deep within.

. This sense of being accepted comes in the first instance from other human beings. But all human acceptance is fragile. Ultimately we need a sense of being accepted unconditionally. Only if God accepts me, and I become convinced of this, do I know definitively: it is good that I exist. It is good to be a human being. If ever man's sense of being accepted and loved by God is lost, then there is no longer any answer to the question whether to be a human being is good at all. Doubt concerning human existence becomes more and more insurmountable. Where doubt over God becomes prevalent, then doubt over humanity follows inevitably. We see today how widely this doubt is spreading. We see it in the joylessness, in the inner sadness, that can be read on so many human faces today. Only faith gives me the conviction: it is good that I exist. It is good to be a human being, even in hard times. Faith makes one happy from deep within.

Those words were part of the conclusion of the Holy Father's address yesterday to the Curia, in which he shared Christmas greetings and reflected on the past year. The work by Pieper (1904-97) mentioned by Benedict XVI is part of the outstanding book, Faith Hope Love, published by Ignatius Press (and also available in e-book format), one of the finest reflections on the theological virtues ever written. (I relied heavily on Pieper's insights in my essay, "Love and the Skeptic", which contains several quotes from the book.) For more about Pieper's life, thoughts, and many books, visit his Ignatius Insight page:

Why do words matter? (Hint: Because we use them in prayer and worship.)

An excellent answer to that important question is given by Fr. Douglas Martis and Christopher Carstens in Mystical Body, Mystical Voice: Encountering Christ in the Words of the Mass (published by the Liturgical Institute at the University of Saint Mary of the Lake and Liturgy Training Publications), which is excerpted in the November 2011 edition of Adoremus Bulletin:

Words are sacramental, which means they contain and convey the reality they speak.

Homo sapiens is a talking animal, communicating with the senses, by word of mouth, pen and paper, telephone, electronic message, magazine, radio, television, and image. So voluminous is this communication, we often speak of "information overload". We also acknowledge with a common expression this inflation of language — "talk is cheap", and as a result we often "pay lip service" to it. Liturgical language, on the other hand, is never "cheap", by no means wasted, and in no way empty. As sacramental signs, the words of the Mass in some way cause, contain, and convey their meaning: ultimately, these signs must point us to the reality, which is Christ Himself. By virtue of the sacramental connection between sacramental words and their supernatural reality, when the Church speaks her Mystical Voice, she says what she believes and means what she says.

What does she mean? Better yet, whom does she mean? She means Christ, her Spouse, the eternal Son of God, and our Redeemer. In the Word made flesh, Jesus undoes our own disobedience (literally, our "not listening") to the voice of God by His own perfect obedience, thus allowing men and women to enter into the eternal dialogue of love within the Trinity. When the Church speaks, she joins her Mystical Voice with that of Christ her Head, speaking with Him His "yes" to the Father's design. The sacramental words of the Mass, cultivated from divine and human sources, are the words of the Lord and His Church in this dialogue of Trinitarian love. The words of the Church speak this divinized language; when words become individualized or idiosyncratic, they speak a language that is not her own, thus symbolizing a different reality.

The precision of the Church's sacramental language, consequently, expresses the reality of Christ the Logos and fosters a supernatural — and Logical — response from us. When the Church determines the words of the Mass, it is not a matter of mere semantics, for her sacramental words must correspond to the Word they signify. To use obscure, novel, or imprecise language causes, in the end, an obscure, novel, or imprecise reality. As there are rules governing any language, the "grammar" that defines the Church's mystical language is determined by Church doctrine and history. Catholic belief and Catholic language are closely related. Words mean things; and in the Church's liturgy, they mean Christ.

That serves as a good preface to three essays that I came upon this week, each of them remarking on specific prayers that have benefited from the new translation of the Roman Missal:

• "New translation will deepen, enrich our prayer together" (Catholic New World, Dec. 18, 2011), by Fr. Robert Barron, which looks at three prayers. "What marks these new texts?" asks Fr. Barron. "They are, I would argue, more courtly, more theologically rich and more Scripturally poetic than the previous prayers — and this is all to the good."

• "One prayer, but it says so much" (The Catholic Register, Dec. 13, 2011), by Fr. Raymond J. de Souza. "First, the new translation has forced us to go back to basics, and nothing is more basic and fundamental than the "source and summit" of the Catholic faith", writes Fr. de Souza. "The new translation has meant that the entire Church in Canada has engaged in a sustained catechesis on the Mass."

• "Revealing overlooked Roman Missal changes" (Our Sunday Visitor, Dec. 11, 2011), by Barry Hudock. "In all the hoopla leading up to the implementation of the new edition of the Roman Missal in the United States, most of the attention has focused on the new principles used to translate its contents from the original Latin to English. Though questions about 'dynamic equivalence' or 'formal equivalence' are important and interesting, other changes — arguably more important ones — have barely been mentioned", writes Hudock. "Here's one: There's a eucharistic prayer in the new Missal that simply wasn't in the old Sacramentary. Here's another: Three eucharistic prayers that were in the old books are now absent from the new one."

December 22, 2011

Pope Benedict XVI reviews 2011 with cardinals and Curia

From Vatican Information Service:

VATICAN CITY, 22 DEC 2011 (VIS) - This morning the Holy Father received cardinals along with members of the Roman Curia and of the Governance of the Vatican City State for the traditional exchange of Christmas and New Year's greetings. Speaking for those present, Cardinal Angelo Sodano, dean of the College of Cardinals, greeted the Pontiff.

In his following address [which can be read in its entirety on the Vatican website], Benedict XVI reviewed the major events of this year, which has been marked by "an economic and financial crisis that is ultimately based on the ethical crisis looming over the Old Continent. Even if such values as solidarity, commitment to one's neighbour and responsibility towards the poor and suffering are largely uncontroversial, still the motivation is often lacking for individuals and large sectors of society to practise renunciation and make sacrifices". That is why "the key theme of this year, and of the years ahead, is this: how do we proclaim the Gospel today?" in a way that the faith may be the living force that is absent today.

In this respect, the Pope noted that "the ecclesial events of the outgoing year were all ultimately related to this theme. There were the journeys to Croatia, to the World Youth Day in Spain, to my home country of Germany, and finally to Africa – Benin – for the consignment of the Post-Synodal document on justice, peace and reconciliation ... Equally memorable were the journeys to Venice, to San Marino, to the Eucharistic Congress in Ancona, and to Calabria. And finally there was the important day of encounter in Assisi for religions and for people who in whatever way are searching for truth and peace".

Other important steps in the same direction were the establishment of the Pontifical Council for the New Evangelization, which points "towards next year's Synod on the same theme", and the proclamation of the Year of Faith.

Without Revitalizing the Faith, Church Reform Will Remain Ineffective

To all of this is joined the reflection on the need for reform within the Church. "Faithful believers ... are noticing with concern that regular churchgoers are growing older all the time and that their number is constantly diminishing; that recruitment of priests is stagnating; that scepticism and unbelief are growing. ... There are endless debates over what must be done in order to reverse the trend. There is no doubt that a variety of things need to be done. ... The essence of the crisis of the Church in Europe ... is the crisis of faith. If we find no answer to this, if faith does not take on new life, deep conviction and real strength from the encounter with Jesus Christ, then all other reforms will remain ineffective".

In contrast to the European situation, Benedict XVI asserted that during his trip to Benin "none of the faith fatigue that is so prevalent here ... was detectable there. Amid all the problems, sufferings and trials that Africa clearly experiences, one could still sense the people's joy in being Christian, buoyed up by inner happiness at knowing Christ and belonging to His Church. From this joy comes also the strength to serve Christ in hard-pressed situations of human suffering, the strength to put oneself at his disposal, without looking round for one's own advantage. Encountering this faith that is so ready to sacrifice and so full of happiness is a powerful remedy against the fatigue with Christianity such as we are experiencing in Europe today".

Another sign of hope is seen in the World Youth Days where "again and again ... a new, more youthful form of Christianity can be seen", one possessing five main characteristics. "Firstly, there is a new experience of catholicity, of the Church's universality. This is what struck the young people and all the participants quite directly: we come from every continent, but although we have never met one another, we know one another" because "the same inner encounter with Jesus Christ has stamped us deep within with the same structure of intellect, will, and heart. ... In this setting, to say that all humanity are brothers and sisters is not merely an idea: it becomes a real shared experience, generating joy".

Secondly, "from this derives a new way of living our humanity, our Christianity. For me, one of the most important experiences of those days was the meeting with the World Youth Day volunteers: about 20,000 young people, all of whom devoted weeks or months of their lives" to the preparations. "At the end of the day, these young people were visibly and tangibly filled with a great sense of happiness: their time had meaning; in giving of their time and labour, they had found time, they had found life. ... These young people did good, even at a cost, even if it demanded sacrifice, simply because it is a wonderful thing to do good, to be there for others. All it needs is the courage to make the leap. Prior to all of this is the encounter with Jesus Christ, inflaming us with love for God and for others, and freeing us from seeking our own ego". The Pope recalled having found the same attitude in Africa from the Sisters of Mother Teresa "who devote themselves to abandoned, sick, poor, and suffering children, without asking anything for themselves, thus becoming inwardly rich and free. This is the genuinely Christian attitude".

The Joy of Knowing We Are Loved by God

The third element characterizing the World Youth Days is adoration. Benedict XVI remarked on the crowds' silence before the Blessed Sacrament in Hyde Park, Zagreb, and Madrid. "God is indeed ever-present", he said. "But again, the physical presence of the risen Christ is something different, something new. ... Adoration is primarily an act of faith – the act of faith as such. God is not just some possible or impossible hypothesis concerning the origin of all things. He is present. And if He is present, then I bow down before him. ... We enter this certainty of God's tangible love for us with love in our own hearts. This is adoration, and this then determines my life. Only thus can I celebrate the Eucharist correctly and receive the body of the Lord rightly".

Confession is another essential characteristic of the World Youth Days because, with this sacrament "we recognize that we need forgiveness over and over again, and that forgiveness brings responsibility. Openness to love is present in man, implanted in him by the Creator, together with the capacity to respond to God in faith. But also present, in consequence of man's sinful history ... is the tendency ... towards selfishness, towards becoming closed in on oneself, in fact towards evil. ... Therefore we need the humility that constantly asks God for forgiveness, that seeks purification and awakens in us the counterforce, the positive force of the Creator, to draw us upwards".

Fifthly, and finally, the Pope mentioned the joy that above all depends on the certainty, based on faith that "I am wanted; I have a task; I am accepted, I am loved. ... Man can only accept himself if he is accepted by another. ... This sense of being accepted comes in the first instance from other human beings. But all human acceptance is fragile. Ultimately we need a sense of being accepted unconditionally. Only if God accepts me, and I become convinced of this, do I know definitively: it is good that I exist. ... If ever man's sense of being accepted and loved by God is lost, then there is no longer any answer to the question whether to be a human being is good at all. ... Only faith gives me the conviction: it is good that I exist. It is good to be a human being, even in hard times. Faith makes one happy from deep within".

In conclusion, the Pontiff thanked the Curia for "for shouldering the common mission that the Lord has given us as witnesses to His truth" and them wished all a blessed Christmas.

"The meaning of our Christian holy days is not primarily ..."

... our external holiday celebration, but that particular mysteries of God happen to us, and that we respond. Something in the deepest center of our being is meant here, more than the exterior symbols can even indicate. Anyone who lacks spiritual eyes, and whose soul has not become open and watchful, will not understand the reason we  are so often festive in the cycle of the liturgical year. The Church stands before us with great gestures and great pomp and ceremonial rites. This is only an attempt to indicate something that reaches much deeper and must be taken much more seriously.

are so often festive in the cycle of the liturgical year. The Church stands before us with great gestures and great pomp and ceremonial rites. This is only an attempt to indicate something that reaches much deeper and must be taken much more seriously.

We need to celebrate holy days in three ways. First, by recalling a historical event. The feasts are always based on verifiable, historical facts. We should not just get carried away with unbridled enthusiasm. What is really going on? This is a question of discernment and recognition. Seen from God's perspective, there is always a clearly defined event connected to the mystery, a clear statement intended, a fact.

This brings us to the second point. Within all of the foregoing, a great mystery--the Mysterium--is hidden. Something happens between Heaven and earth that passes all understanding. This mystery is made present to us, continues in the world till the end of time, and is always in the process of happening--the abiding Mysterium.

These two points are followed by the third way in which we must consider the feast to be serious and important. Through the historical facts and through the workings of the mystery, the holy day simultaneously issues a challenge to each individual life, a message that demands a particular attitude and an interior decision from each person to whom it is proclaimed.

The Christmas celebration is the birth of the Lord. It is verifiable that Christ was born on this night. The great mystery behind this is the marriage covenant of God with mankind; that mankind is fulfilled only insofar as it has grown into this covenant. Concretely, it is meaningful to establish what this covenant, which began between divinity and humanity on that Holy Night, signifies as a challenge and message for each one of us.

Read more of this pre-Christmas homily, which was preached on this day, December 22, in 1942, in Munich:

Carl E. Olson's Blog

- Carl E. Olson's profile

- 20 followers