Carl E. Olson's Blog, page 251

January 1, 2012

Mary, more Mother than Queen

From an excellent essay, "Theosis: The Final Mystery of the Rosary", by Stratford Caldecott, on the Second Spring website:

The mystery of theosis, it seems to me, is something we need to be reminded of today more than ever, at the end of a secular age in which so many have tried to live as though God did not exist. The vision of Mary, crowned with flowers on earth and with stars in heaven, is the one image of human destiny that can stand up against the hedonistic vision, the corrupted imagination and  impure heart of the decadent twentieth century. It can, of course, too easily be presented as a pretty picture with no connection to everyday life, and to the everyday struggle for sanctity. Mary, after all, did not have to "struggle" for holiness. Mary is unique: how can her special privileges be of concern to us, except indirectly? We see in this common attitude another effect of the longstanding dualism between nature and grace, discussed earlier. By being "preredeemed", by being conceived Immaculate, by being assumed bodily into heaven, many feel that Mary has been removed from the natural sphere and placed in the supernatural. But what has in fact been lost here is the sense that Mary is the heart of the Church of which we are the members. If the only fulfilment of nature is through grace, then she who is full of grace shows us the fulfilment of our own natures also. To her state we may also attain - even if only in the partial way appropriate to our less central position in the Mystical Body, and through a process of purification that for her is unnecessary. She does not have to struggle for sanctity, but she suffers with us in our struggle, and accompanies us, not in the useless way of a person who makes all the same mistakes, but in the helpful way that can support us with unfailing patience, compassion and wisdom.

impure heart of the decadent twentieth century. It can, of course, too easily be presented as a pretty picture with no connection to everyday life, and to the everyday struggle for sanctity. Mary, after all, did not have to "struggle" for holiness. Mary is unique: how can her special privileges be of concern to us, except indirectly? We see in this common attitude another effect of the longstanding dualism between nature and grace, discussed earlier. By being "preredeemed", by being conceived Immaculate, by being assumed bodily into heaven, many feel that Mary has been removed from the natural sphere and placed in the supernatural. But what has in fact been lost here is the sense that Mary is the heart of the Church of which we are the members. If the only fulfilment of nature is through grace, then she who is full of grace shows us the fulfilment of our own natures also. To her state we may also attain - even if only in the partial way appropriate to our less central position in the Mystical Body, and through a process of purification that for her is unnecessary. She does not have to struggle for sanctity, but she suffers with us in our struggle, and accompanies us, not in the useless way of a person who makes all the same mistakes, but in the helpful way that can support us with unfailing patience, compassion and wisdom.

The commonly voiced objection to any renewed emphasis on the Coronation is that already noted (in connection with Balthasar) that by giving attention to the Queenship of Mary we may lose sight of her maidenly humility as sister and friend. St Thérèse of Lisieux in a reflection on the Coronation similarly remarks that the Blessed Virgin is "more Mother than Queen": a mother does not want to eclipse the glory of her children but make them shine more brightly. The danger of that would be lessened in the context of a theological synthesis that made clear the nature and purpose of Marian devotion. But is could be argued (on historical as well as theological grounds) that whenever the Mother of God is "downgraded" the saints are sure to follow, until even the concept of sanctity is lost.

In any case, Pope John Paul II, in his encyclicals and numerous weekly audiences on Mary, has shown that Mary's "state of royal freedom" flows precisely from her humility as handmaid, mother and sister. In the Kingdom of God, to serve means to reign. The phrase is one he picks up from Vatican II (Lumen Gentium, 36), and quotes in Section 41 of Redemptoris Mater (1987). It is true of Christ, who "came not to be served but to serve, and to give his life as a ransom for many," becoming first a child, then a prisoner, then a dead man; entering the glory of his kingdom in this very way. It is true of any disciple of Jesus, and it is true above all for his Mother. The Pope goes on to say that the "glory of serving does not cease to be her royal exaltation: assumed into heaven, she does not cease her saving service, which expresses her maternal mediation 'until the eternal fulfilment of all the elect.' Thus, she who here on earth 'loyally persevered in her union with her Son unto the Cross,' continues to remain united with him, while now 'all things are subjected to him, until he subjects to the Father himself and all things.' In her Assumption into heaven, Mary is as it were clothed by the whole reality of the Communion of Saints, and her very union with the Son in glory is wholly oriented towards the definitive fullness of the Kingdom, when 'God will be all in all'."

If Mary is, as the Catechism tells us in one of its headings, an eschatological icon of the Church, it is in the figure of the Virgin Mary, united with Christ in heaven, that our destiny and calling as human beings are most fully revealed to us. Mary is already the Church that we are summoned to become through repentance and purification. She is nature perfected in a single person, and transfigured by the grace to which she offers not the faintest shadow of resistance. It is the image of her "Coronation" or eschatological transfiguration that most fully expresses the final effects of grace on nature: the integration of human life with the life of the eternal and ever-blessed Trinity.

Read the entire essay. As a companion piece, see my essay, "Theosis: The Reason for the Season".

December 31, 2011

A simple question:

If you were to:

• claim to have accomplished something that, in fact, you weren't capable of doing (lying),

• that you did not have the authority to do (dissenting),

• that violated the very nature of what you said you were doing (causing scandal),

• and that openly attacked the authority and structure of the community which you claimed to be serving in humility and truth (rebellion and deception),

do you think you would be the subject of an endless stream of newspaper articles extolling your actions, your cause, your conscience, and your courage? No? Maybe? Not sure?

By the way, here's a little blast from the past regarding the same issue. The more things change...

"Mary is the purely human form of the divine will to save."

The brilliant Erasmo Leiva-Merikakis on the relationship between Mary and the her Son's disciples:

Because a Christian disciple is above all a Christ-bearer, there exists a deep and indispensable relationship between Jesus' disciples and the Mother of Emmanuel. By an ineffable design of his grace, God has appointed us to be the visible manifestation of Jesus Christ in the world, the visibility of him who is the Son common to the living God and the humble Virgin of Nazareth. It was she who first made him visible among us, this Virgin whose childbearing, in Isaiah's promise, is inseparable from her Son's labor to "save his people from their sins".[1] We, too, should carefully take to heart the angel's words to Joseph: "Do not fear to take Mary your wife, for that which is conceived in her is of the Holy Spirit."[2]

Now, this communion with the Mother of Jesus, far from being an eccentric and misguided departure from the purity of the Gospel, is precisely that to which the Lord Jesus is calling us if we would follow him perfectly.

When in Luke 11:28 Jesus proclaims the great beatitude: "Blessed . . . are those who hear the word of God and keep it", surely he intends a great deal more than simply the observance of specific commandments. For the "Word of God", used in the singular and in such a solemn proclamation, must refer above all to Jesus himself as eternal Son of the Father, especially in the context of an anonymous woman declaring Mary's womb to be blessed for having borne him as Savior. Likewise, the Greek word [phulassontes] in this same context conveys much more than simply "observing" or "keeping": indeed, its full range of associations extends to "defending", "cherishing", "fostering' safeguarding", all meanings directly relevant to the conception, bearing, and rearing of a child.

"To keep the Word of God", as Jesus enjoins, cannot at bottom mean anything other than allowing the Holy Spirit to implant the Son of the Father in the womb of our Souls, and then for us to give birth to this Word into the world in union with Mary, the historical Mother of Jesus and the perennial Mother of the Church. The kerygmatic birth of Jesus into the world from the womb of the apostles' faith cannot be a substantially different birth from the historical one that took place in Bethlehem, for there is only one Christ Jesus. The "keeping of the Word of God" in this sense is in full harmony both with the Father's proclamation at the Transfiguration ("This is my beloved Son ... ; listen to him"[3]) and with Mary's advice to the guests at Cana ("Do whatever he tells you!"[4]).

Both the Father and the Mother point to the incarnate Word with love and pleasure. The Holy Spirit conceives him in us, and the Word, bent on redeeming us, points to himself as revelation of the Father. Mary is the purely human form of the divine will to save.

To be a Christian and a disciple, then, means becoming Christ-bearers in the world in the most radical and literal sense. However, such a visible presence and communication of the total Jesus through us cannot occur without our being in constant communion with both the Father and the Mother of Jesus, the two origins of his divine and human life. The Holy Spirit cannot accomplish the fullness of redemption in us, cannot effect the conception of the Son of the Most High within us–and we cannot become another Mary, the Christian vocation in a nutshell – unless we seek the company of her through whom and in whom he is permanently present, not only among the choirs of angels in union with his Father and their Spirit, but also visibly and humanly in his Church and within the landscape of this world, so wretched yet so graced.

"Every one who believes that Jesus is the Christ is a child of God, and every one who loves the parent loves the child."[5] This is the descending order of love in John: If you love the parent, you must also love the child, which here refers both to Jesus himself and to those begotten by faith in his messiahship, Must we not also hold this order of love with regard to Jesus' human Mother? If we love Jesus as Son of the only Father, can we avoid, without a grave breach of all decency, loving his only Mother? We love Jesus for the sake of the Father, and we love Mary for the sake of Jesus and the Father, and thus our love for her is not based on whim or mere sentiment, but on the firm foundation of God's own trinitarian Being and of the economy of redemption he has wrought.

"Going into the house [the Magi] saw the child with Mary his mother, and they fell down and worshiped him."[6] It is impossible to find Jesus in isolation from the two essential communities to which he belongs by his nature as incarnate Word. In his divinity we cannot embrace him apart from the community of the Holy Trinity; and in his humanity we cannot approach him apart from the family through which he enters our race and shares our human condition to the full. "What God has joined together, let no man put asunder."[7]

As the Magi find him "with Mary his mother", they "fall down and worship him". Note well two things here: first, that they worship only Jesus, but, at the same time, that in bowing down in adoration before him they must necessarily incline with reverence in the direction of the Virgin Mother who is holding him out to them and to the world. Thus, worship of Jesus is inseparable from deep reverence for the Mother by whose obedient faith he has come into the world and made himself available for our own adoration. Mary's faith has thus made it possible for us to adore God incarnate!

Read more:

Theotokos sums up all that Mary is

From an Advent/Christmas column I wrote a few years ago:

God has a mother and she was chosen before the beginning of time.

This is an amazing belief, one that is sometimes mocked and often misunderstood, and misrepresented, sometimes even by Catholics. Yet this truth is at the heart of Advent and Christmas–as well as at the heart of the entire Christian Faith.

This belief is also captured in a short phrase in the Hail Mary: "Holy Mary, Mother of God." They are just five simple words, but words bursting with mystery and meaning. They tell us many things about Mary and about the Triune God and His loving plan of salvation for mankind, in which Mary has such a significant place.

Mary is holy. To be holy is to be set apart, to be pure, and to be filled with the life of God. The call to holiness, the Catechism of the Catholic Church states, is summarized in Jesus' words: "Be perfect, as your heavenly Father is perfect" (Matt 5:48; CCC 2013). Mary's holiness comes from the same source as the holiness that fills all who are baptized and are in a state of race. But Mary's relationship with the Triune God is unique, as Luke makes evident in his description of Gabriel appearing to Mary:

"And the angel answered and said to her, 'The Holy Spirit will come upon you, and the power of the Most High will overshadow you; and for that reason the holy offspring shall be called the Son of God" (Lk 1:35)"

Possessing perfect faith, itself a gift from God, Mary was overshadowed by God the Father, anointed by the Holy Spirit, and filled by the Son. She was chosen by God to bear the God-man, the One in whom the "whole fullness of deity" would dwell (CCC 484). Completely filled by God, she is completely holy. Chosen by God, she is saved. Called to share intimately and eternally in the life of her Son, she was, the Catechism explains, "redeemed from the moment of her conception" (CCC 49) and "preserved from the stain of original sin" (CCC 508).

The Pentateuch contains the account of how God chose a small, nondescript nomadic tribe, the Hebrews, to be His "holy people" for "His own possession out of all the peoples who are on the face of the earth" (Deut 7:6). Many years later, in the fullness of time, God chose a young Jewish woman from a place of little consequence to be the Mother of God. This, in turn, would result in the birth of the Church, which Peter describes as a "chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, a people for God's own possession" (1 Pet 2:9).

Mary, faithful and holy, is chosen so that others can also be chosen and made holy, transformed by her Son into the sons and daughters of God and joined to the Body of Christ. Mary "is the Virgo fidelis, the faithful virgin, who was never anything but faithful," writes Fr. Jean Daniélou, "whose fidelity was the perfect answer to the fidelity of God; she was always entirely consecrated to the one true God."

It has been said many ways and in many places but bears repeating that "Mother of God" is the greatest and most sublime title that Mary can ever be given. It sums up all that she is, all that she does, and all that she desires. The title of Theotokos ("God-bearer", or "Mother of God"), far from being some late addition to Church teaching, is rooted in Scripture and the Advent story. The Catechism explains that Mary was "called in the Gospels 'the mother of Jesus'" and that she "is acclaimed by Elizabeth, at the prompting of the Spirit and even before the birth of her son, as 'the mother of my Lord'" (CCC 495).

Mary, the Mother of God, is also the first disciple of her Son, the God-man. She is also the New Eve, whose obedience and gift of her entire being overturns the sin and rebellion of the first Eve. Her Son is the New Adam, who comes to give everlasting, supernatural life and heal the mortal wound inflicted by the sin of the first Adam (cf. 1 Cor 15:45).

Mary, the virginal mother of God, and feminist theology

From Fr. Manfred Hauke's book, God or Goddess?: Feminist Theology: What is it? Where Does it Lead? (Ignatius Press, 1995):

Mary, the virginal mother of God, is a kind of central point at which the main lines of the Catholic Faith come together. Since it is impossible to conceive of sacred history without her, she points in a unique way toward the mystery of Christ and the Church. By virtue of that position, she also becomes a criterion against which new theological conceptions  must be measured. Mary's criteriological significance is of supreme value when assessing feminist theology, which puts forward demands for fundamental changes in religious life.

must be measured. Mary's criteriological significance is of supreme value when assessing feminist theology, which puts forward demands for fundamental changes in religious life.

Mary Daly's and other Feminist Critiques of Mariology

The decisive impulse to theological feminism's critique of Mariology came in 1973, from Mary Daly's Beyond God the Father. Already in 1968, Daly published a book on the theme of women, its title and basic content closely tied to Simone de Beauvoir: The Church and the Second Sex. For Daly, too, one does not arrive in the world as a woman, but one becomes a woman. In view of the theory of evolution, we can no longer speak of an "essence" of man or of woman or, likewise, of an immutable God who grounds immutable orders of things. Hence, there are no longer any creation-imposed presuppositions to serve as standards for the transformation of society and the Church, but only the ideal of "equality."

In her 1973 critique, Daly has been inspired once again by Simone de Beauvoir, who had pointed out the contrast between the ancient goddesses and Mary as early as 1949; whereas the goddesses commanded autonomous power and utilized men for their own purposes, Mary is wholly the servant of God: "'I am the handmaid of the Lord.' For the first time in the history of mankind," writes Beauvoir, "a mother kneels before her son and acknowledges, of her own free will, her inferiority. The supreme victory of masculinity is consummated in Mariolatry: it signifies the rehabilitation of woman through the completeness of her defeat."

Daly now sharpens this critique and puts it in a wider systematic context: Mary is "a remnant of the ancient image of the Mother Goddess, enchained and subordinated in Christianity, as the 'Mother of God'." To this attempt to "domesticate" the mother goddess, Daly opposes a striving to bring together the divine and the feminine.

In the later work Gyn/Ecology (1978), Daly abandons the ideal of "androgyny" that she had previously still advocated and becomes the most important representative of the gynocentric "goddess feminism." Mary is a "pale derivative symbol disguising the conquered Goddess," a "flaunting of the tamed Goddess." Her role as servant in the Incarnation of God amounts to nothing other than a "rape." For Daly, the subordination of man to God is something negative, especially when this state of affairs is expressed in a feminine symbol such as Mary.

Mary as a "domesticated goddess" – this basic notion of Daly's is not something original to feminism. The same objection can be found, from another perspective and primarily since the nineteenth century, in liberal polemics against the Catholic teaching on Mary. Particularly, the title "Mother of God" is often explained in terms of the common people's need to worship a goddess. It seems unnecessary to discuss this "unsellable" item from anti-Catholic polemics further here. Whereas, however, the anti-Catholic literature of earlier generations found it important to stress that Mary is no goddess, the feminists emphasize Mary's place-holding function: Mary discloses the female attributes of God that have heretofore been suppressed.

Read more from this section of Fr. Hauke's book. For more about Mary Daly's work, see my post, "Mary Daly, radical elemental feminist, God-hater, man-basher, self-described..." (January 2010).

December 30, 2011

A dose of reality about Christopher Hitchens, RIP...

... courtesy of Dr. Edward Feser (himself a former atheist), in case you missed his post of two weeks ago:

Christopher Hitchens, who had been suffering from esophageal cancer for over a year, has died. I think I first came across his work around 1990, at the time his book Blood, Class, and Nostalgia appeared. (My copy is still around here somewhere.) I recall seeing him on television -- grilling some George H. W. Bush administration official, perhaps -- and being very impressed by his forceful and formidable intelligence. I have always been conservative and have usually disagreed with him, but I followed his work with interest from that point on, long before he started to please right-wingers with his well-argued criticisms of the Clintons and support for the Iraq war. He was almost always smart, funny, and interesting even when he was wrong.

Except on religion, where he was a complete bore and an insufferable hack. There is no use sugar-coating that fact now that he is gone, and Hitchens was not in any event a fan of the polite obituary. Religion is the last subject about which to have a tin ear or a closed mind, and Hitchens had both. Some Catholics seem to have gotten it into their heads over the last year that he might convert -- as if someone who is overtly so very hostile to Catholicism simply must be compensating for a secret longing for it, and is sure to be moved by the prospect of imminent death to let his inhibitions fall away. This struck me as romantic fantasy, born of too steady a diet of happy "crossing the Tiber" stories. Sometimes a man has mixed feelings about you, but will accentuate the negative, loath as he is to acknowledge the merits of an adversary. And sometimes he just hates your guts, and that's that. As far as I know, Hitchens was no closer on his deathbed to becoming the next Malcolm Muggeridge than he had been when penning his decidedly un-Muggeridgean book about Mother Teresa. I very much hope I am wrong.

Read the entire post on Feser's blog. I've read a few of Hitchens' articles over the years and readily acknowledge his exceptional writing ability. But I was actually embarrassed for him when I read God Is Not Great. It was so bad you'd be forgiven for thinking, "Was this actually penned by a lobotomized undergraduate at a fourth-rate college who was injected with huge doses of God-hating, Christian-despising serum?" Regardless, while praying that God has mercy on Hitchens' soul, I think Feser is absolutely right in saying, "And sometimes he just hates your guts, and that's that." Indeed.

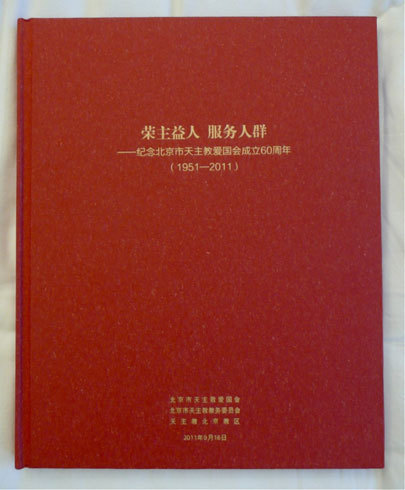

China's leading bishop openly declares support for the Communist Party

From Dr. Anthony E. Clark, this follow-up note to his recent article, "China's Catholics: Sixty Years of Faith, Resistance, and Reaching for Freedom" (Ignatius Insight, Dec. 28, 2011):

As radical nationalism reaches a fevered pitch in China, the country's official Catholic leader, Beijing's Bishop Li Shan published recently his testimony in support of China's Communist Party and declared China's Church is "independent, self ruling, and self managing."

Bishop Li's anti-Rome remarks come just a few months after he defied Vatican orders not to ordain bishops illicitly; Li's refusal to obey Rome has caused grave rifts in China's Catholic community, as he has become increasingly pro-Party, and has proudly announced his chairmanship of Beijing's Catholic Patriotic Association. Here is a preliminary translation of Bishop Li's "Introduction" to the "Sixtieth Anniversary Celebration of Beijing's Catholic Patriotic Association," published in October 2011.

____________

Introduction

On September 16, 1951, the first meeting of Beijing's Catholics was solemnly convened under the guidance of the Holy Spirit, and 500 Catholic clergy represented Beijing's 30,000 Christians. They resolutely determined to cast off the shackles of colonialist and capitalist control for a more unpolluted Holy Church, so that the Holy Church can continue to transmit the Gospel. In support of and under the leadership of the Communist Party and a New China, they worked together with their compatriots to establish a Socialist society. The Patriotic Religious Organization was established at the great meeting to resolutely advance an independent, self-ruling, and self-managing Church: this was called the Beijing Catholic Patriotic Association. From that moment Beijing's Catholics entered a new glorious era of evangelization.

For sixty years now the Beijing Catholic Patriotic Association has rallied together and guided the clergy, who have raised high the banner of the Catholic Patriotic Association, determined to firmly go down the road of being an independent, self-ruled, and self-managed Church. We enthusiastically promote the governance and rights of the Patriotic Association, and direct ourselves toward the aim of the collective education of the clergy, who together with the Party and government are linked together by a common purpose. The diocesan and administrative committees work together toward the goals of pastoral evangelization, earnestly work serve the interests of society, energetically work to serve the whole, to serve the capital, to serve humanity, and witness "the love of Jesus," and implement the sacred commission, "that they may all be one," to the glory of the Son.

+ Li Shan

Chairman of the Beijing Catholic Patriotic Association

Chairman of the Beijing Catholic Service Committee

Bishop of Beijing

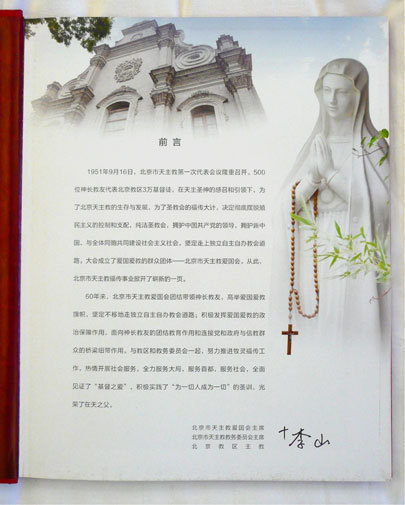

Below are photos (from top to bottom) of Bishop Li Shan (left), the cover of the program for the "Sixtieth Anniversary Celebration of Beijing's Catholic Patriotic Association", and the original, Chinese text of Bishop Shan's introduction:

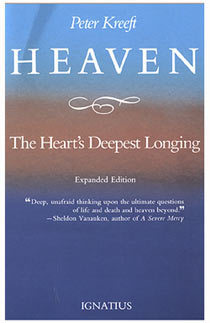

Peter Kreeft: "Of all the questions the human mind can ask, three are of ultimate importance:"

1. What can I know?

2. What should I do?

3. What may I hope?

The three questions [1] correspond to the three "theological virtues" of faith, hope, and charity. [2] Faith in God's word is the Christian answer to "What can I know?" Love of God and neighbor is the Christian answer to "What should I do?" And hope for Gods' Kingdom, the Kingdom of heaven, is the Christian answer to "What may I hope?" Just as faith fulfills the mind's deepest quest for truth and as love fulfills the moral will's deepest quest for goodness, so the hope of heaven fulfills the heart's deepest quest for joy.

It is the quest that moves irrepressibly through the world's great myths and religions, the masterpieces of its greatest artists and writers, and the dreams that rise from the primordial depths of our unconscious. However different the heavens hoped for, wherever there is humanity, there is hope.

The question of hope is at least as ultimate as the other two great questions. For it means "what is the point and purpose of life? Why was I born? Why am I living? What's it all about, Alfie?"

Most people in our modern Western society do not have any clear or solid answer to this question. Most of us live without knowing what we live for. Surely this is life's greatest tragedy, far worse than death. Living for no reason is not living, but mere existing, mere surviving. As Viktor Frankl found in a Nazi concentration camp, our deepest, rock-bottom need is not pleasure, as Freud thought, or power, as Adler thought, but meaning and purpose, "a reason to live and a reason to die". [3] We need a meaning to life more than we need life itself.

Millions all around us are living the tragedy of meaningless life, the "life" of spiritual death. That is what makes our society more radically different from every society in history: not that it can fly to the moon, enfranchise more voters, have the grossest national product, conquer disease, or even blow up the entire planet, but that is does not know why it exists.

Every past society gave its members answers to all three great questions. It transmitted the teachings of its sages, saints, mystics, gurus, philosophers, or gods through tradition. For the first time in history, society no longer regards tradition as sacred; in fact, it no longer regards it at all. We are the first tree that has uprooted itself from the universal soil. If we are to find an answer to the question "For what may I hope?" we must find the answer individually; our society simply does not know. The only sound we hear from our noisy society concerning the most important questions in the world is the sound of silence.

How has this silence come about? How is it that the society that "knows it all" about everything knows nothing about Everything? How has the knowledge explosion exploded away the supreme knowledge? Why have we thrown away the road map just as we've souped up the engine? We must retrace the steps by which we have come to this dead end; to recapture hope we must diagnose the causes of our hopelessness before we begin to prescribe a remedy. Before we undertake the main task of this book, the exploration of the deepest hope of the human heart, the hope for heaven, we must first answer two preliminary questions: first, why our society is so silent, and second, how our hearts can substitute for our society in being our teachers and guides on our quest for hope, our quest for heaven.

The History of Hope

From earliest times, humanity has hoped for heaven. The earliest artifacts are burial mounds. The dead were always prepared for the great journey. However various the forms, belief in an afterlife is coterminous with humanity.

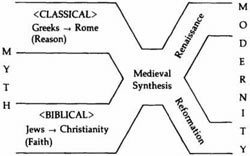

Among ancient peoples two stand out in this respect, as in most others: the Jews and the Greeks. These peoples are the twin sources of Western civilization, the two main tributaries of the river whose waters, blending in the medieval synthesis and separated again in modernity, still trickle far downstream through the swampy delta of the present. They were the only two peoples who found modes of thought other than myth for answering life's three great questions. For myth the Jews substituted faith in a historically active and word-revealing God, and the Greeks substituted critical inquiring reason. For this reason, they developed different hopes, different heavens, from those of the myths.

The Hebrew conception of heaven arises in exactly the opposite way from the pagan one; instead of rising out of humanity's heart, it descends from God's. From the beginning of the story, God tells humanity what he wants instead of humanity telling God what it wants. Instead of humanity making the gods in its image, God makes humanity in His image; and instead of earth making heaven in its image, heaven makes earth in its image. Thus the greatest Jew teaches us to pray: "Thy kingdom come ... on earth as it is in heaven."[4]

The Jews are "the chosen people"--through no merit of their own, God insists--chosen to be the messengers of hope for the world, the world's collective prophet, God's mouthpiece.[5] God teaches them, and through them the world, three things: who he is, what they must do, and for what they may hope. For the third, he promises many things, some obscure, some incredible, as when he says he will raise the dead. [6] God says he will show them something (whether on this earth or not is obscure) that "eye has not seen, ear has not heard, nor has it entered into the heart of man." [7]

The good Jew therefore does not speculate about heaven. If it has not entered into "the heart of man," well then, whatever has entered into "the heart of man" is not it. Let God define it and provide it, not humanity. Only when God speaks do we know with certainty, and when God speaks obscurely, we know only obscurely. Jews, unlike Christians, do not believe God has spoken clearly about the afterlife (at least not yet), and they will not run ahead of God--a proper and admirable restraint when contrasted with the extravagant myths of the rest of the world, who succumb to the irresistible temptation to fill in with human imagination the gaps left in God's revelation.

The Greeks are the other root of the tree of Western civilization. The Jews gave us conscience; the Greeks, reason. The Jews gave us the laws of morality, of what ought to be; the Greeks gave us the laws of thought and of being of what is. And their philosophers discovered a new concept of God and a new concept of heaven. While the priests were repeating their stories of fickle and fallible gods with their Olympian shenanigans and imaginative afterworlds, underworlds, or overworlds, the philosophers substituted impersonal but perfect essences for the personal but imperfect gods and a heaven of absolute Truth and Goodness for one of pleasures or pains. Not Zeus, but Justice, not Aphrodite, but Beauty, not Apollo, but Truth were the true gods: perfect unpersons rather than imperfect persons. (The Jews, meanwhile, were worshipping the Perfect Person, transcending the Greek alternatives.) The heaven corresponding to the Greek philosophers' theology was a timeless, spaceless realm of pure spirit, pure mind, pure knowledge of eternal essences instead of the priests' gloomy underworlds of Tartarus and Hades, earthly otherworlds of Elysian Fields, or astronomical overworlds of heroes turned into constellations.

Two of these heavenly essences stand out as ultimate values: Truth and Goodness. Even the gods are judged by these values and found wanting; that is why Socrates was executed, for "not believing in the gods of the State". [8] Plato asks, "is a holy thing holy because the gods approve it, or do the gods approve it because it is holy?" [9] The priests say the former; the philosophers, the latter. For them the two eternal essences, Goodness and Truth, stand above the Greek gods. But they do not stand above the Jewish God, the God who is Goodness and Truth, emeth, fidelity, trustworthiness. The Greeks discovered two divine attributes; the Jews were discovered by the God who has them.

Hebraism and Hellenism meet--Hebraism in its Christianized form, Hellenism in its Romanized form. But these forms remain Hebraic and Hellenic in substance. Christ was not an alien import; he did not ask Jews to convert to a new religion but claimed to be their prophets' Messiah. And Rome remained a Greek mind in a Roman body. The Empire added emperors aplenty, the material accoutrements of roads, armies, and political power, but not one important new philosophy.

The meeting and blending of these two great rivers, the biblical (Judeo-Christian) and the classical (Greco-Roman) produced the Middle Ages. Medieval thinkers were intensely conscious of being inheritors and synthesizers, preservers and blenders of two ancient foods. As medieval theology synthesized the personality of YHWH (incarnated in Christ) with the timeless perfection of the philosophers' essences, the medieval picture of heaven synthesized the biblical imagery of love and joyful worship of God with the Greek philosophical heaven of the contemplation of eternal Truth.

But the Middle Ages are no longer. The Renaissance and the Reformation disintegrated the medieval synthesis, divorced the couple that had been stormily but creatively married. These two sources of modernity both harked back to pre-medieval ideals: the Renaissance longed to return to Greco-Roman humanism and rationalism, and the Reformation longed to return to a simple biblical faith.

From the Reformation emerged a Protestantism whose essential vision of human destiny was in agreement with medieval Catholicism, since both were rooted in biblical revelation. But from the Renaissance emerged something radically new in human history: a secular society with a secular summum bonum. Of the twenty-one civilizations Toynbee distinguishes in his monumental Study of History, the first twenty kept some sort of religious basis and purpose; ours is history's most unique experiment. It remains to be seen how long a civilization can survive without the use of spiritual energy, without a supernatural source of life.

What purpose is substituted for the service of God and the hope of heaven? The conquest of nature, first by the ineffective attempt of magic, then by the reliable way of technology. But the difference between these two means is minor compared to the difference between their common new end and the common old end: "There is something which unites magic and applied science while separating both from the 'wisdom' of earlier ages. For the wise men of old the cardinal problem had been how to conform the soul to reality, and the solution had been knowledge, self-discipline, and virtue. For magic and applied science alike, the problem is how to subdue reality to the wishes of men: the solution is a technique."[10]

This new purpose in life is logically connected with a new vision of the nature of reality, for one's life view and world view (Lebenschauung and Weltanschauung) hang together. As long as the nature of ultimate reality was thought to be trans-human--some sort of God or gods--our fundamental relation to reality was to conform, not to conquer. But once the gods drop out of view and "reality" comes to mean merely material nature--the subhuman, not the superhuman--our life's business is not to conform to it but to conquer it for our own purposes. Bacon trumpets the new age with slogans like "knowledge for power" and "Man's conquest of Nature."[11] These replace the "impractical" and "passive" traditional goals of knowledge for truth and of being conquered by God.

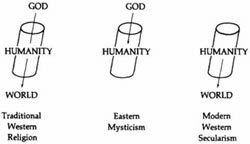

Think of humanity as a tube with two openings. The openings can be either open or closed, as we choose. Think of God, or superhuman reality, as above the tube, and nature, or subhuman reality, as below it. Traditional religious wisdom tells us to be open at both ends so God can flow in one end and out the other: in the receptive end first by faith and then out the active end by works. But if the top opening is closed, our business becomes exclusively human action in the world, without a plug-in to divine power. This is technologism, "Man's conquest of Nature."

There is a third possibility: the tube could be closed at the bottom and open at the top. This would characterize Hinduism and Buddhism, for which the world is illusion (maya) or temptation, and the sole end of life is the realization of oneness with trans-human ultimate reality. Oriental mysticism minimizes worldly action; modern Western secularism denies receptivity to God; and the classical Western tradition synthesizes the two, giving priority to the God-relationship, for we must first be directed by God before we can wisely direct our world.

There is a third possibility: the tube could be closed at the bottom and open at the top. This would characterize Hinduism and Buddhism, for which the world is illusion (maya) or temptation, and the sole end of life is the realization of oneness with trans-human ultimate reality. Oriental mysticism minimizes worldly action; modern Western secularism denies receptivity to God; and the classical Western tradition synthesizes the two, giving priority to the God-relationship, for we must first be directed by God before we can wisely direct our world.Once modernity denies or ignores God, there are only two realities left: humanity and nature. If God is not our end and hope, we must find that hope in ourselves or in nature. Thus emerge modernity's two new kingdoms, the Kingdom of Self and the Kingdom of This World: the twin towers of Babel II. Judging by the outcome of Babel I, the prognosis does not look good.

The Two Modern Idol-Kingdoms

An idol is anything that is not God but is treated as God: any creature set up as our final end, hope, meaning, and joy. Anything--anything--can be an idol. Religion can be an idol. Religion is not God but the worship of God; idolizing religion means worshipping worship. That's like being in love with love rather than with a person. Love too can be an idol, for "God is love" but love is not God. Every divine attribute, separated from the divine person, becomes an idol. God is Truth, but Truth is not God. God is just, but Justice is not God. The first commandment is surely the one most frequently broken, and the apostle John does well to end his first letter with the warning, "Little children, keep yourselves from idols." [12]

Since an idol is not God, no matter how sincerely or passionately it is treated as God, it is bound to break the heart of its worshipper, sooner or later. Good motives for idolatry cannot remove the objective fact that the idol is an unreality. "Food in dreams is exactly like real food, yet what we eat in our dreams does not nourish: for we are dreaming." [13] You can't get blood from a stone or divine joy from nondivine things.

There are two idols, two false kingdoms, in the modern world rather than just one because the modern world is a split world, an alienated world, a world of dualism. Humanity and nature, siblings from a common Father, became alienated from each other when humanity, nature's priest and steward, became alienated from God. In the Genesis story thorns and thistles appear after Adam's Fall, and pain in childbirth for Eve. [14]

The alienation between humanity and nature begun at the Fall is exacerbated by Renaissance humanism, and its two forms herald the two modern idol-kingdoms. First, the southern European Renaissance places humanity in the foreground and God in the background; then the northern European Renaissance puts nature in the foreground and the road to utopia becomes the conquest of nature.

Descartes, the father of modern philosophy and child of both Renaissances, separates humanity and nature more sharply than ever before. Humanity's essence is merely mind and nature's is merely matter; and mind and matter are two clear and distinct ideas. For mind does not occupy space, but matter does; and matter does not have any consciousness, but mind does. The fact that we find the mind-matter distinction clear and self-evident is a measure of how influential Cartesian dualism is.

But the alienation is not merely between ourselves and nature but also within ourselves between mind and body. Descartes sees the human being as a "ghost in a machine," a pure spirit or mind in a purely material body, and we have no idea how a ghostly finger can push the buttons of a bodily machine. [15] We do not recognize ourselves in this picture of the ghost in the machine; yet it is the picture to which modern common sense naturally gravitates. We know we are not ghosts in machines, but we do not know what we are. We know reality cannot be two totally different and unconnected things, but we do not know what reality ultimately is--that is, if "we" are typically modern.

The overcoming of dualism is monism--but a monism of what? Matter or spirit? Both solutions have emerged in modern philosophy. LaMettrie and Hobbes are early modern materialists; Spinoza and Leibnitz are early modern spiritualists. Materialism reduces spirit to matter; spiritualism reduces matter to spirit. Later, with Kant, spiritualism changes from an objective to a subjective spiritualism. Ever since Kant, the modern dualism has been not merely between matter and spirit but between objective matter and subjective spirit. The two idol-kingdoms are built in these two realms: the Kingdom of This World in the realm of objective matter at the expense of spirit and the Kingdom of the Self in the realm of subjective spirit at the expense of the objective. Subjective truth replaces objective truth; subjective values replace objective values. Both kingdoms are alternatives to the Kingdom of God, which is built in the realm of objective spirit. God is objective spirit, and when "God is dead," the objective world is reduced to matter and the spiritual world is reduced to subjectivity. That is our dualism.

To overcome this dualism and to relieve the anxiety its alienation causes, we take refuge in one or the other of the two monisms. We dare not see both halves of our split personality at once. Buber writes memorably about this in an image:

At times the man, shuddering at the alienation between the I and the world, comes to reflect that something is to be done. ... And thought, ready with its service and its art, paints with its well-known speed one--no, two rows of pictures, on the right wall and on the left. On the one there is ... the universe. ... On the other wall there takes place the soul .... Thenceforth, if ever the man shudders at the alienation, and the world strikes terror in his heart, he looks up (to right or left, just as it may chance) and sees a picture. There he sees that the I is embedded in the world and there is really no I at all--so the world can do nothing to the I, and he is put at ease; or he sees that the world is embedded in the I, and that there is really no world at all--so the world can do nothing to the I, and he is put at ease.

But a moment comes, and it is near, when the shuddering man looks up and sees both pictures in a flash together. And a deeper shudder seizes him. [16]

The only overcoming of that deeper shudder of alienation is in the common Father of I and world. Thus Buber's next line is, "the extended lines of relations meet in the eternal Thou."

Endnotes:

[1] Emmanuel Kant, Critique of Pure Reason, trans. Norman Kemp Smith (New York: Macmillan, 1958), p. 635: "All the interests of my reason, speculative as well as practical, combine in the three following questions: (1) What can I know? (2) What ought I to do? (3) What may I hope?"

[2] Aquinas. Summa Theologiae I-II. 62, 3.

[3] Viktor E. Frankl, Man's Search for Meaning (New York; Washington Square Press, 1963). Cf. John Powell, A Reason to Live, A Reason to Die (Niles, Ill.: Argus Communications, 1972).

[4] Matt. 6:10. Scriptural quotations are from the Revised Standard Version unless otherwise noted.

[5] Deut. 7:6-8.

[6] Isa. 25:8; Ezek. 37:12-14; Job 19:25-27.

[7] 1 Cor. 2:9 cf. Isa. 64:4, 65:17.

[8] Plato, Apology of Socrates 24b.

[9] Plato, Euthyphro 10a.

[10] C. S. Lewis, The Abolition of Man (New York: Macmillan, (1965), pp. 87-88.

[11] Francis Bacon, Magna Instauratio, Preface; Novum Organum 2. 20.

[12] 1 John 5:21.

[13] Augustine, Confessions 3. 6.

[14] Gen. 3:16-19.

[15] The phrase is from Gilbert Ryle. The Concept of Mind (New York: Barnes & Noble, 1949).

[16] Martin Buber, I And Thou, trans. Ronald Gregor Smith (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1958), pp. 70-72.

Related IgnatiusInsight.com Articles:

• Interview with Peter Kreeft | August 2004

• Seducing Minds with the Socratic Method | Peter Kreeft

• Socrates Meets Sartre: In Hell? | Peter Kreeft

• How To Read the Bible | Peter Kreeft

• The Presence of Christ in "The Lord of the Rings" | Peter Kreeft

• Introduction to Three Approaches to Abortion | Peter Kreeft

• The Point Of It All | Peter Kreeft

Peter Kreeft, Ph.D., is a professor of philosophy at Boston College. He is an alumnus of Calvin College (AB 1959) and Fordham University (MA 1961, Ph.D., 1965). He taught at Villanova University from 1962-1965, and has been at Boston College since 1965.

He is the author of numerous books (over forty and counting) including: C.S. Lewis for the Third Millennium, Fundamentals of the Faith, Catholic Christianity, Back to Virtue, and Three Approaches to Abortion. More info about Kreeft and his many Ignatius Press books can be found on his IgnatiusInsight.com author page.

December 29, 2011

On Hitchens, Havel, and Kim—and Totalitarianism

From Paul Kengor, prolific author and professor of political science at Grove City College:

They say that famous people die in groups of three.

I recently heard the news of the death of Christopher Hitchens, one of the world's best-known atheists and polemicists. I was saddened by Hitchens' death. I'm no atheist, but I respected the man, his writing skills, and his fierce independence of mind. When I got the news, I immediately did what Hitchens might have done: I started writing, trying to collect my feelings into words. It's how I cope with things.

Two days later, on a Sunday morning, a friend of mine at church grabbed my arm and whispered: "Did you hear that Vaclav Havel died?"

No, I hadn't. That one hurt, too. Havel is one of a handful of individuals responsible for the collapse of communism. I've lectured on the man. As I sat in the pew, I began writing again—in my head.

When I got home, I hurriedly composed an article on Havel and Hitchens both. Hitchens, ironically, had great respect for Havel, conceding Havel's crucial role in communism's collapse. He did not, however, agree with Havel on matters of faith. Havel was Roman Catholic, and saw in God the source of our fundamental freedoms. Havel extolled the inalienable rights of the Declaration of Independence, and the One who endows those rights. Hitchens, by contrast, called God a "totalitarian." Havel lived under totalitarianism, one of its victims, and viewed God as the purest response to totalitarianism.

Later that day, Sunday evening, I attended a Christmas play. A colleague of mine, a fellow professor, was in the play. We were discussing the deaths of Hitchens and Havel, and the parallels. My friend recalled November 22, 1963, a remarkable day when John F. Kennedy, C. S. Lewis, and Aldous Huxley all died. We nervously chuckled: "Well, who will be the third person to die this time?"

At that very moment, our answer was unfolding in North Korea: it was Kim Jong-Il. And therein is more irony: Kim was the anti-Havel.

Read the entire article on the Center for Vision & Values website.

The Pope's year in review...

... in short form, courtesy of Vatican Information Service:

VATICAN CITY, 29 DEC 2011 (VIS) - In a recent interview on Vatican Radio, Holy See Press Office Director Fr. Federico Lombardi S.J. reviewed the activities of the Holy Father over the course of 2011. A summary of his remarks is given below.

Fr. Lombardi first turned his attention to the Pope's trips, noting that the visit to Germany in September had reflected the Holy Father's concern to speak to modern secularised society, especially in Europe, about God and His primacy. By contrast, his visit to Spain for World Youth Day was "a great experience of the vitality of the faith, of its future". In Benin, Benedict XVI had signed the Post-Synodal Apostolic Exhortation "Africa munus" in which he examines the problems facing Africa and "identifies reasons for realistic hope with which to face the future, recognising the dignity of the African people", Fr. Lombardi said.

Another key moment of 2011 was the inter-religious meeting at Assisi in October, which had focused on "the search for truth". The event had been attended not just by representatives of different religious confessions, but also by "people who, though they do not recognise a God, sincerely seek after the truth".

Among the documents published during 2011, Fr. Lombardi mentioned the Motu Proprio "Porta Fidei" with which Benedict XVI proclaims a "Year of Faith" to begin in October 2012. This, he noted, is associated with one of the great themes of the pontificate: new evangelisation. The Holy See Press Office Director also recalled the recent Mass to mark the independence of various Latin American countries, during which the Pope had announced his forthcoming trip to Mexico and Cuba.

At Christmas every year the Holy Father makes special visits of solidarity, and this year's took him to the Roman prison of Rebbibia where he gave spontaneous answers to questions put to him by the inmates. That meeting, said Fr. Lombardi, shows "how the Church, though recognising that civil society has legislative responsibility for dramatic issues such as justice and prisons, ... can send out a strong message ... about reconciliation, hope and reintegration into society".

Also during 2011 the Pope was able to speak with astronauts orbiting the earth on the international space station, "thus underlining with great willingness and joy the Church's benevolence towards scientific research and technology, when they serve the good of humanity". The beatification of John Paul II was another key moment of the past year, which "mobilised the entire Church" and was experienced "with immense delight".

The year also saw the publication of part two of Joseph Ratzinger's book "Jesus of Nazareth", focusing on the death and resurrection of Christ. "We continue to hope", Fr. Lombardi concluded, "that he will write a third volume, on the infancy, in order to complete this extraordinarily vivid and profound presentation of Jesus for us today".

Here is much more about Pope Benedict XVI and his many writings.

Carl E. Olson's Blog

- Carl E. Olson's profile

- 20 followers