Carl E. Olson's Blog, page 16

May 21, 2016

Reading Flannery O’Connor for the First Time

Reading Flannery O’Connor for the First Time | Dr. Kelly Scott Franklin | CWR

She gleefully maimed and killed off her characters in a million disturbing ways—and she was a devout, daily mass Catholic who read St. Thomas Aquinas in her spare time and made a pilgrimage to Lourdes.

Reading Flannery O’Connor requires a stout heart and a strong stomach.

In her short life before she died of terminal lupus, she wrote two novels and roughly two dozen short stories that continue to shock and unsettle us. With a wicked pen, she gleefully maims and kills off her characters in a million disturbing ways: they get drowned, hanged, run over by cars (twice in a row), wrapped in barbed wire and beaten to death. Her characters are prostitutes, pedophiles, arsonists, murderers, nihilists, and (worst of all for O'Connor), salesmen. But if you read her biography, she’s practically the patron saint of Catholic fiction: a devout, daily mass Catholic who read St. Thomas Aquinas in her spare time, and made a pilgrimage to the Shrine of Our Lady of Lourdes.

As readers, we wonder, “Is there something I’m missing?” How should we read O’Connor’s writing, and where is her faith in the pages of such brutal fiction?

Readers of O’Connor will notice that most of her stories follow one basic Biblical narrative: St. Paul on the road to Damascus. Again and again, she depicts an event of searing violence in which divine grace shocks a hard-hearted, wicked, or selfish person into a moment of recognition. In this terrible moment O’Connor offers her characters a choice, a flash of self-knowledge, and an encounter with God that utterly burns away their illusions.

O’Connor does this best in one of my favorite tales, titled “Good Country People,” where she tells the story of Hulga, a nihilist with a Ph.D. in philosophy and a wooden leg.

May 18, 2016

Biblical preaching and healing the culture

"The Ascension" (1305) by Giotto [WikiArt.org]

By George Weigel | The Dispatch at CWR

At the root of today’s culture of happy-go-lucky hedonism, which inevitably leads to debonair nihilism, is a profound deprecation of the human.

If Catholics in the United States are going to be healers of our wounded culture, we’re going to have to learn to see the world through lenses ground by biblical faith. That form of depth perception only comes from an immersion in the Bible itself. So spending ten or fifteen minutes a day with the word of God is a must for the evangelical Catholic of the twenty-first century.

Biblical preaching that breaks open the text so that we can see the world, and ourselves, aright is another 21st-century Catholic imperative.

There is far too little biblically-based catechetical preaching, at which the Fathers of the Church in the first millennium excelled, today. The Church still learns from their ancient homilies in the Liturgy of the Hours, but the kind of expository preaching the Fathers did is rarely heard at either Sunday or weekday Masses. It must be, though, if the Church’s people are to be equipped to convert and heal contemporary culture. For the first step in that healing process is to penetrate the fog, see ourselves for who we are, and understand our situation for what it is.

How might biblical preaching help us do that?

Take the recent Solemnity of the Ascension as an example. The essential truth of the Ascension is that it marked the moment in salvation history at which humanity – glorified humanity, to be sure, but humanity nonetheless – was incorporated into the thrice-holy God. The God of the Bible is God-with-us, Emmanuel. But, with the Ascension and Christ’s glorification “at the right hand of the Majesty on high” (Hebrews 1:3), humanity is “with God.” If the Incarnation, Christ’s coming in the flesh, teaches us that God is not distant from us, and if the Passion teaches us that God is “with us” even in suffering and death, then the Ascension teaches us that one like us is now “with God,” and indeed in God. Which means that humanity is capable of being sanctified, even divinized.

Eastern Christian theology calls this theosis, “divinization,” and it’s a hard concept for many western Christians to grasp. Yet here is what St. Basil the Great, one of the Cappadocian Fathers of the Church, teaches about the sending of the Holy Spirit, promised in Acts 1:8 at the Ascension: “Through the Spirit we acquire a likeness to God; indeed we attain what is beyond our most sublime aspirations – we become God.” What can that possibly mean?

May 17, 2016

Lord, Not Legend: A Review of Brant Pitre’s "The Case for Jesus"

Lord, Not Legend: A Review of Brant Pitre’s

The Case for Jesus |

Dr. Leroy Huizenga | Catholic World Report

The new book by a notable young Scripture scholar addresses both the dominant paradigm in academic biblical studies and the more popular errors about Jesus and the New Testament.

A Tale of Two Paradigms

The dominant paradigm reigning in academic biblical studies today is marked by radical discontinuity. That’s why people who know the basics of the Christian story—whether they believe it or not—are often nonplussed when they encounter radical reconstructions of Jesus and earliest Christianity. Others, of course, applaud them, finding that such radical reconstructions get them off the hook with the traditional Jesus and the Church. Gone is the Jesus who saves us, replaced by a Jesus who either affirms us, or is ultimately irrelevant, or who encourages whatever vague spirituality is du jour. In either case, they are presented with a reconstruction in which Jesus is alone, cut off, isolated—divorced from Judaism, from the Old Testament, from the Gospels, from the Church. The real Jesus, radical reconstructions insist, is some sort of mystic, or revolutionary, or Cynic, or teacher, or prophet, whose Judaism is incidental and irrelevant at best and who has been hidden—often deliberately—by the later dogma of the Church, even by the biblical Gospels themselves.

By contrast, traditional Christianity (whether Catholic, Protestant, Orthodox, or fundamentalist) sees Jesus in terms of continuity. In broad strokes, he fulfills the Old Testament promises, and the Gospels of the Church (however conceived) faithfully record eyewitness accounts of His Virgin Birth, miracles, prophecy, and teaching, his sacrificial death, his bodily resurrection, as well as his commissioning of the apostles to go and make disciples of all nations.

The dominant paradigm reigning in academic biblical studies today was developed largely by German scholars of a Lutheran confessional persuasion in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. D. F. Strauss suggested the disciples made up almost everything in the Gospels out of Jewish legends, while Rudolf Bultmann claimed not only that the Old Testament could not be considered Scripture for Christians (and thus irrelevant for understanding Jesus) but also that most everything in the Gospels was a post-Easter retrojection back into the life of Jesus and thus that we can know next to nothing about the historical Jesus. Meanwhile scholars such as Heinrich Holtzmann were busy arguing that Mark, and not Matthew, was written first among the Gospels, while Walter Bauer was arguing that orthodoxy didn’t exist until history’s victors in what became the later Church invented it, with Adolf von Harnack contending similarly that later Christian dogma was an imposition upon the Gospels, the earliest Church, and Jesus himself.

The dominant paradigm reigning in academic biblical studies today, being developed originally by Germans prior to the horrors of the Holocaust, is also laden with anti-Catholicism and anti-Semitism of a genteel but not necessarily virulent sort. While some like Bultmann did join the Confessing Church and oppose the Nazis, others like von Harnack were busy finding ways to deny Jewish scholars important professorships. In any event, to enlightened German Lutheran eyes, Judaism and Catholicism were cut from the same cloth. They belonged to the old world of sacrifice and ritual which the Reformation and its child the Enlightenment had buried forever. It would be inconceivable to such scholars that common, normal Judaism could inform our understanding of Jesus or earliest Christianity—this is why Germans excelled at exploring Greco-Roman backgrounds—or that Jesus and the earliest Church could be understood in Catholic terms.

The greatest contemporary popular exponent of the dominant paradigm today is Dr. Bart Ehrman, Professor of Religious Studies at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, a former fundamentalist whose forays into textual criticism made him a liberal Christian for a time but ultimately an unbeliever. A friendly convivial fellow and a serious, sober scholar, neither an anti-Catholic nor anti-Semite, Ehrman has sold millions of books popularizing the paradigm of discontinuity in several books, in which he endeavors to show the Gospels are unreliable and that Jesus was an apocalyptic prophet far different from the Jesus Christ the Church has worshipped as divine son of God.

Pitre Revives Lewis’ Trilemma

Brant Pitre’s most recent popular offering, The Case for Jesus: The Biblical and Historical Evidence for Christ (Image, the Catholic imprint of Doubleday, 2016), has Ehrman’s work as its gentle target as Pitre presents a spirited defense of the tradition paradigm of continuity among Judaism, the Old Testament, Jesus, and the Gospels. (Full disclosure: I wrote a positive blurb of an advance draft of the book.)

Interestingly, Pitre doesn’t discuss Jesus’ continuity with the Catholic Church, probably be cause he wishes to present an argument congenial to Christians and seekers of all stripes, even as his presentation would be fully at home in Catholic Christianity. Indeed, he begins with an Anglican, the famous C.S. Lewis, who offered the famous “trilemma”: a man who said the sorts of things Jesus did about himself was either a liar, a lunatic (“on the level with a man who claimed to be a poached egg”), or Lord. As most people don’t want to concede Jesus was deceived or deceptive, Lewis’ logic is designed to force readers to accept the third, fateful, option: Jesus was, and is, Lord.

Lewis, a man of letters who expressed explicit disdain for Bultmann and German scholarship, accepted the Gospels’ testimony about Jesus self-presentation as true. At this point the radical paradigm of discontinuity raises its head in protest, however, claiming as Ehrman does that there’s a fourth option that Lewis dismissed: the Gospels do not in fact represent the truth about Jesus, that the Gospels are largely legendary. All, then, hinges on the Gospels’ reliability. If they present Jesus faithfully, then Lewis’ trilemma works. If not, it doesn’t. And so Pitre offers a tour-de-force showing that the Gospels do indeed do so.

The book falls into two parts.

May 14, 2016

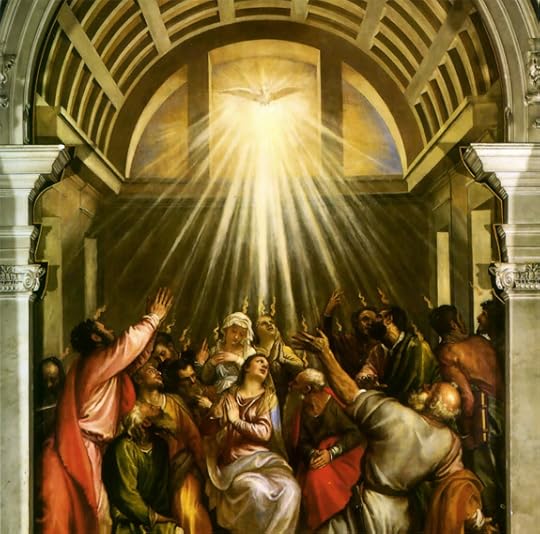

Three Births and the Third Person of the Trinity

"Pentecost" by Titian (c. 1545) [WikiArt.org]

Three Births and the Third Person of the Trinity | Carl E. Olson

On the Readings for Sunday, May 15, 2016, Pentecost Sunday

Readings:

• Acts 2:1-11

• Ps 104:1, 24, 29-30, 31, 34

• 1 Cor 12:3b-7, 12-13 or Rom 8:8-17

• Jn 20:19-23 or Jn 14:15-16, 23b-26

He is silent, yet sounds like rushing wind; he is invisible, but appears as tongues of fire; he is constantly working and giving, but is often overlooked and underappreciated.

He is the Holy Spirit, the Lord and giver of Life, the third Person of the Trinity. He has many names in Scripture, including Advocate, Comforter, the Spirit of God, the Spirit of Christ, the Spirit of adoption, the Spirit of grace.

In the second chapter of the Acts of Apostle, the coming of the Holy Spirit is described as “a noise like a strong driving wind” and his presence as “tongues as of fire.” Notice how elusive the language is: the Holy Spirit is not a driving wind, but is like such a wind; he is not a tongue of fire, but appears as one. There is a paradox here, which is so often the case with the Holy Spirit: he is both very elusive and yet constantly active. It’s as though you see something or someone out of the corner of your eye, but no matter how quickly you turn, they are gone.

Isn’t this the sense conveyed by Jesus, who said to Nicodemus, “The wind blows where it wills, and you hear the sound of it, but you do not know whence it comes or whither it goes; so it is with every one who is born of the Spirit” (Jn. 3:8)? The word “born” is deeply significant for there are three very important births, or creations, described in Scripture in which the Holy Spirit moves and acts, giving life.

These three births are closely connected. First, there is the birth of the cosmos and the creation of the world: “The earth was without form and void, and darkness was upon the face of the deep; and the Spirit of God was moving over the face of the waters” (Gen. 1:2). There it is again: the Spirit was moving. Pope John Paul II, in his encyclical on the Holy Spirit, Dominum et vivificantem (Pentecost, 1986), further notes that the presence of the Spirit in creation not only pertains, of course, to the cosmos, but also to “man, who has been created in the image and likeness of God: ‘Let us make man in our image, after our likeness.’” (par. 12).

The second instance is the conception of the God-man, Jesus Christ. What did the angel say to Mary? “The Holy Spirit will come upon you, and the power of the Most High will overshadow you; therefore the child to be born will be called holy, the Son of God” (Lk. 1:35). Once again, the Holy Spirit is active; he is coming with power. Once again, he is intimately involved in bringing about a man. In the first creation it was Adam; now, the new Adam.

The third birth, or creation, took place at Pentecost, fifty days after the death and resurrection of Christ. “The time of the Church began,” wrote John Paul II, “at the moment when the promises and predictions that so explicitly referred to the Counselor, the Spirit of truth, began to be fulfilled in complete power and clarity upon the Apostles, thus determining the birth of the Church” (DV, 25). At Pentecost, the Church—the family of God and the mystical body of Christ—is birthed by the Holy Spirit. And he is the soul of the Church. “What the soul is to the human body,” wrote St. Augustine, “the Holy Spirit is to the Body of Christ, which is the Church” (Catechism of the Catholic Church, 797).

Emile Mersch, S.J., in The Theology of the Mystical Body (Herder, 1952), wrote: “The Holy Spirit is continually being sent, and Pentecost never comes to an end.” The Acts of the Apostles reveals the Holy Spirit “ceaselessly coming down into the world, no longer under the form of fiery tongues, but through the intermediary of the apostles and their preaching.”

He is still coming, filling, moving, and giving life. Let’s pay attention!

(This "Opening the Word" column originally appeared in the May 23, 2010, edition of Our Sunday Visitor newspaper.)

Carl E. Olson on the Catholic theology of human deification

Dr. Adam A. J. DeVille is Associate Professor and Chairman of the Department of Theology-Philosophy, University of Saint Francis (Fort Wayne, IN) and author of Orthodoxy and the Roman Papacy (University of Notre Dame, 2011). He is a regular contributor to Catholic World Report and his "Eastern Christian Books" site is an invaluable source for information about books about Eastern Catholic and Orthodox history, theology, and spirituality. He recently interviewed Carl E. about Called To Be the Children: The Catholic Theology of Human Deification , recently published by Ignatius Press; the two discussed the genesis and purpose of the book, common reactions to the Church's teachings about theosis/deification, misunderstandings about the teaching, the Scriptural foundations for deification, and why this topic is so significant for ecumenical relations between Catholic and Orthodox believers:

, recently published by Ignatius Press; the two discussed the genesis and purpose of the book, common reactions to the Church's teachings about theosis/deification, misunderstandings about the teaching, the Scriptural foundations for deification, and why this topic is so significant for ecumenical relations between Catholic and Orthodox believers:

Though it's been almost a decade since Daniel Keating's book Deification and Grace appeared from Catholic University of America Press, lingering suspicion of divinization or deification in Catholic circles is still to be found, which is staggering and stupid in equal measure. Happily, however, we now have what I hope will be the definitive answer to that nonsense: a new, and wholly welcome, collection of articles co-edited by Carl Olson (my editor, in fact, at Catholic World Report) and the Jesuit priest David Meconi, a patrologist who teaches at Saint Louis University. That collection, Called to Be the Children of God: The Catholic Theology of Human Deification, really, really deserves a place in every Catholic library large and small so that, among other things, it can finally drive a fatal stake through the heart of the foolish notion one still finds in some Catholic circles (including as late last year at a major Catholic university in Europe) that theosis (deification or divinization) is (a) some esoteric and suspect "Eastern" notion held by those "schismatic" Orthodox; (b) something quasi-pagan and therefore suspect; or (c) both of the above.

And what a thoroughly catholic collection it is, too! It really does show the universal breadth of the Church, and some of her many diverse traditions, communities, and expressions. Thus we have, inter alia, chapters on deification in the Latin and Greek patristic traditions; in the Dominican and Franciscan traditions; deification in the French Catholic spiritual tradition; in the neo-Thomistic tradition; in the thought of Cardinal Newman (who was, of course, so deeply immersed in the Fathers, especially the Greeks); in the teaching of Trent, Vatican I, and Vatican II; in the thought of Pope John Paul II; and in the liturgy (a chapter most aptly written by David Fagerberg, author of such works as On Liturgical Asceticism, which, like his break-out book Theologia Prima: What is Liturgical Theology? shows deep immersion in the Christian East).

All this and more is to be found in a handsome book (bearing on the front cover what is my favourite Byzantine icon of all time, Theophanes the Greek's rendition of the Transfiguration) that is both affordable and accessible to your average "lay" reader. This book really does belong in personal and parish libraries as well as those of every Catholic academic institution.

I asked the editors for their thoughts on this book, and Carl was able to respond. Fr. David is engaged in an extended period of travel just now, so I hope to have a chance to hear from him later.

AD: Tell us about your background.

Olson: I was raised in a Fundamentalist Protestant home, and my father was the co-founder of a small Bible chapel in western Montana that is still going strong. One of the great things about my upbringing was the immersion in Scripture, which would later play a key role in my decision to become Catholic and, more specifically, my recognition of the incredible truth of theosis, or deification. After a couple years of art school, I attended Briercrest Bible College in Saskatchewan, Canada, which proved to be a pivotal time for me, as I was (rather surprisingly) exposed to a wide range of Catholic and Anglo-Catholic theology and writing. Not only did I learn a great deal, I also learned how much I didn't know (a lot!), which spurred me on to studying a lot of Church history and theology on my own.

That led, eventually, to the realization that I was reading a lot of Catholic (or Anglo-Catholic) writers--Chesterton, C.S. Lewis, Russell Kirk, and T.S. Eliot stand out--which led to my reading of the early Church Fathers, Newman, Aquinas, and John Paul II. More to the point, I wound up listening to a Scott Hahn tape series "The Catholic Gospel," which was actually a class he taught at the time at Steubenville. His focus was on "divine sonship," and he delved into a wide range of theologians, including Matthias Scheeben (the subject of a chapter in the book), whose Mysteries of Christianity was an eye-opening read. I also read Fr. Emile Mersch's Theology of the Mystical Body, which further impressed upon me the essential truth of deification. I was very happy and honored that Scott graciously wrote the Foreword to the book, because his influence on my own study and thought was substantial.

My wife and I entered the Catholic Church in 1997, and that same year I began working on a Masters in Theological Studies from the University of Dallas, via that school's Institute for Religious and Pastoral Studies. Those three years of theological formation were invaluable for many reasons, not least a firm and deep grounding in the teachings and practices of the Church. This topic continued to be an important one for me, and I ended up writing a paper on the theme of deification in the Catechism of the Catholic Church, which has been revised and included as a chapter in this book.

Finally, I must note that our family has attended Nativity of the Mother of God Ukrainian Catholic Church in Springfield, Oregon, since 2000, and my understanding and appreciation of theosis has deepened even further through the Divine Liturgy, the friendship and teaching of Fr. Richard Janowicz, and the weekly Bible study I've taught there for over fifteen years.

AD: What led you to collaborate on Called to Be the Children of God: The Catholic Theology of Human Deification?

Read the entire interview on Dr. DeVille's "Eastern Christian Books" site.

May 12, 2016

Olson's Resurrection

Olson's Resurrection | Fr. James V. Schall, S.J. | Catholic World Report | The Dispatch

“Resurrection doesn’t mean becoming a spirit but having one’s mortal body transformed into a spiritualized body, a bodily manner of existing wholly animated by the Spirit of God.” — Carl E. Olson, Did Jesus Really Rise From the Dead: Questions and Answers About the Life, Death, and Resurrection of Jesus(Ignatius Press-Augustine Institute, 2016), 172.

I.

Grammarians, logicians, and other rare species that care about the meaning and accuracy of words in a language might wonder just what the title of these reflections might mean. First of all, just who is this “Olson”? Are we implying, as the order of the words can mean, that this Olson gentleman has somehow been “resurrected” among us? Just what does “resurrection” mean, after all? Is it just another word for medical “resuscitation” so that, like Lazarus, the revivified will live a while longer only to die again? Does the title refer to those “after-death” experiences that scientists these days are busily investigating? Would not this “resurrected” Olson mean, in logic, that he had been dead for some time so that he might need some assistance in getting back on his feet again? The currently living, after all, do not need to be “quickened”, as they quaintly used to say, though they may need to be incited into thinking accurately about these things.

Well, the “Olson” in question is none other than Carl Olson, the editor of this very Catholic World Report web site. He resides in Oregon, where no one, based on my numerous visits there, seems to possess, as yet, a resurrected body. I understand, though, that, if someone is in a hurry, the state’s pioneer “assisted death” laws can quickly dispatch anyone from this life into the great beyond. Once there, if he is not happy in his new digs, he might request a resurrected body sooner than he originally thought.

Olson is an unabashed fan of the Oregon Ducks, though I am not sure if this adds any further credibility to his well-articulated arguments about the resurrection. I have not yet consulted him on the new mandatory requirement at Oregon State University that every student must undergo “social justice training” to matriculate there. Given what this “training” probably means in terms of ideology, it sounds like a totalitarian mandate if I ever heard one. But Olson lives in Eugene, not Corvallis.

II.

In any case, “Olson’s Resurrection” refers to his very readable new book Did Jesus Really Rise From the Dead: Questions and Answers About the Life, Death, and Resurrection of Jesus, which examines, in question and answer form, the basic issues about the resurrection of Christ. A significant amount of literature, one accumulating over the centuries since the event itself, has denied the resurrection of Christ itself or one of its basic implications. Since this doctrine and fact of the resurrection, as St. Paul said in the beginning, are the stones on which the faith rests, the only real way to undermine Christianity is to deny, explain away, ridicule, or otherwise seek to show that such an event never did or could have happened. It was, it is often claimed, contradictory, unscientific, incoherent, unhistorical, or all of the above Many fancy and sophisticated attempts, on-going over the centuries, try to explain that Christ’s resurrection could not possibly mean what it is taken to mean, namely, that Christ did what He claimed that He would do, or what the Father would do for Him. He would rise from a very terrible death administered in Jerusalem at the hands of Roman and Jewish officials during the reign of Tiberius Caesar.

Olson recognizes that the only way that one can deal with the denial of something presented as a fact is to examine the reasons and evidence given for this denial. And the historical reasons given are legion. The history of theology and science has been filled with ingenious and fanciful efforts to show why the resurrection never happened. People, especially intellectuals, seem to realize that they must deal with this extraordinary claim that Christ did rise from the dead. For if it is true, it cannot just be passed off as if nothing important for the human race really happened in the cosmos. We could, for instance, maintain that Christ never existed. Problem solved. Olson goes through the evidence given against Christ’s historical existence. It turns out that there is just as much evidence, if not more, for the existence of Christ as for any other historical character of his time. To deny Christ’s existence is a dead end street, followed only by those who choose to be willfully blind to the evidence.

Well, let’s admit Christ existed. But He was not God, right?. Who was He then? A nice guy? A fraud? An imagination of the Apostles? A revolutionary? A madman? A deluded visionary? Each of these avenues has been tried again and again. None of them, on examination, squares with the evidence we have of what Christ was in the era in which He lived. A favorite line is that the risen Jesus was a mythical creation, or some projected spirit of the imagination of the Apostles who, in their disappointment at His death, projected this return. He was never really there. He was only “imagined”. From the evidence, the people who would be most annoyed by this thesis would be the Apostles themselves, whose testimony gives no indication that they ever thought the resurrected Christ was anything but real flesh and blood.

As Olson shows, the last people who really expected the resurrection were the Apostles themselves. Right up to the end, moreover, they kept thinking that He would restore the Kingdom of Israel in this world as a political entity. Interestingly, as I have sought to show in my book, The Modern Age, this effort to make a perfect kingdom in this world to be the mission of the collective human race is the principal alternative to Christ’s personal resurrection and what it portends to be the real and final destiny of each human being who ever actually existed in this world. The Apostles were themselves a bit slow to catch on to what Christ was teaching them. Christ was patient with them. He just kept correcting them about what He was talking about.

But Christ did what He told the Apostles that He would do—that is, He would suffer at the hands of the Jewish and pagan authorities, die, rise again, and finally return to His Father. This sequence, repeated over and over again in the New Testament, is what happened. After the events and the Ascension and Pentecost, the apostles looked back more carefully on what happened and how they were involved in the whole situation. They began to see that Christ died and rose “according to the Scriptures.” That is how they came to explain what had happened. They learned that Christ’s Incarnation, life, and death, was in fact the central point of the redemptive plan that the Father had worked out all along.

III.

Olson examines each principal historical effort to explain why Christ did not rise as He said.

May 11, 2016

“God became a human, so humans could become God”? Catholic scholars explain human deification in new book

The first generations of Christians saw in their new lives in Jesus Christ a way to transcend all the limitations of sin and death and become new creatures. St. Peter expressed this as “participating in the divine nature” (2 Pet 1:4), while St. Athanasius stated it succinctly 300 years later: “God became a human, so humans could become God.” This is the heart of the Christian faith and the pledge of the Christian promise: that those baptized in Christ become “divine” through their partaking in God’s own life and love. This is why Christians can live forever, this is the source of their charity and their holiness, this is why we do not need to live in a world ruled by fallen instinct and sinful desires. We have been made for more, for infinitely more.

A new book, Called to Be the Children of God: The Catholic Theology of Human Deification , offers essays from more than a dozen Catholic scholars and theologians to examine what this process of “deification” means in their respective areas of study. Editors Fr. David Meconi, S.J. and Carl E. Olson have gathered fifteen chapters showing what “becoming God” meant for the early Church, for St. Thomas Aquinas and the greatest Dominicans, the significance it played in the thinking of St. Francis and the early Franciscans. It shows how such an understanding of salvation played out during the Protestant Reformation and the Council of Trent, as well as in French School of Spirituality, in various Thomist thinkers, in John Henry Newman and John Paul II, at the Vatican Councils, and where such thinking can be found in the Catechism of the Catholic Church today.

, offers essays from more than a dozen Catholic scholars and theologians to examine what this process of “deification” means in their respective areas of study. Editors Fr. David Meconi, S.J. and Carl E. Olson have gathered fifteen chapters showing what “becoming God” meant for the early Church, for St. Thomas Aquinas and the greatest Dominicans, the significance it played in the thinking of St. Francis and the early Franciscans. It shows how such an understanding of salvation played out during the Protestant Reformation and the Council of Trent, as well as in French School of Spirituality, in various Thomist thinkers, in John Henry Newman and John Paul II, at the Vatican Councils, and where such thinking can be found in the Catechism of the Catholic Church today.

No other book has gathered such an array of scholars or provided such a deep study into how humanity’s divinized life in Christ has received many rich and various perspectives over the past two thousand years. This book therefore hopes to bring readers into the central mystery of Christianity by allowing the Church's greatest thinkers and texts to speak for themselves, showing how becoming Christ-like, becoming truly the Body of Christ on earth, is the only ultimate purpose of the Christian faith.

Dr. Scott Hahn, author of Rome Sweet Home and the author of the Forward of Called to Be the Children of God, writes, “Rescue from sin and death is indeed a wonderful thing—but the salvation won for us by Jesus Christ is incomparably greater. And that is the subject of this book. In all its parts, this book, like Christianity in all its parts, is about salvation. But that means it’s about everything that fills our lives, on earth and in heaven.”

“The richness of Catholicism is on full display in these marvelous essays as they show how Scripture’s revelation of theosis is both taught and embodied throughout the Church’s history. I loved reading, pondering, and praying with this marvelous book,” says Dr. Timothy Gray, President of the Augustine Institute and Senior Fellow at St. Paul Center for Biblical Theology.

Dr. Brant Pitre, Professor of Sacred Scripture at Notre Dame Seminary and Graduate School of Theology, says, “At last, we have an up-to-date, comprehensive, and readable introduction to the classical doctrine of divinization. Called to Be the Children of God is a must read for any serious student of Catholic theology.”

“In the explanations of the historical developments of this doctrine, the reader discovers openings into Christian literature that will enrich the spiritual life and theological understanding through deepening our understanding of the effects of God's grace and indwelling, particular through Baptism, the Holy Eucharist and other sacraments,” says Fr. Mitch Pacwa, S.J. of EWTN and Ignatius Productions.

Fr. James V. Schall, S.J., Professor Emeritus of Georgetown University, explains, “To follow the history and meaning of what it means that we exist to be adopted into the Trinitarian life of God is the exact purpose of this most welcome and well-presented text.”

About the Editors:

Fr. David Meconi, S.J., a professor of theology at Saint Louis University, is the editor of Homiletic and Pastoral Review. He has published widely in early Church theology and broader Catholic issues, most recently the Annotated Confessions of Saint Augustine, and The One Christ: St. Augustine’s Theology of Deification.

Carl E. Olson, MTS, is the editor of Catholic World Report and Ignatius Insight. He is the author of two best-selling books, Will Catholics Be “Left Behind”? and The Da Vinci Hoax, and the author of hundreds of articles on theology, Scripture, current events, and apologetics.

Fr. David Meconi, S.J., is available for interviews about this book.

To request a review copy or an interview with Fr. Meconi, please contact: Rose Trabbic, Publicist, Ignatius Press at (239) 867-4180 or rose@ignatius.com

Product Facts:

Title: CALLED TO BE THE CHILDREN OF GOD

The Catholic Theology of Human Deification

Editors: Carl E. Olson and Fr. David Vincent Meconi, S.J.

Release Date: April 2016

Length: 292 pages

Price: $22.95

ISBN: 978-1-58617-947-2 • Softcover

Order: 1-800-651-1531 • www.ignatius.com

The History, Enemies, and Importance of Natural Law

The History, Enemies, and Importance of Natural Law | CWR Staff | Catholic World Report

Philosophy, says Dr. John Lawrence Hill, "played a fundamental role in my conversion to Christianity. I think most non-Christians—at least if they are thoughtful about these matters—really haven’t confronted themselves with the contradictions of their own worldview."

Dr. John Lawrence Hill is a law professor at Indiana University, Robert H. McKinney School of Law in Indianapolis, where he teaches constitutional law, torts, civil procedure and legal philosophy courses. He is the author of several books, including The Political Centrist (Vanderbilt, 2009) and, most recently, After the Natural Law: How the Classical Worldview Supports Our Modern Moral and Political Views (Ignatius Press, 2016). Hill holds a Ph.D. in philosophy and a law degree both from Georgetown University. Formerly an atheist, Hill came into communion with the Catholic Church in 2009. He recently responded to questions from Catholic World Report about what natural law is and is not, common objections to natural law, how natural law developed and how it has been undermined, loss of faith in God in the West and the decline of natural law, and his journey from atheism into the Catholic Church.

(Ignatius Press, 2016). Hill holds a Ph.D. in philosophy and a law degree both from Georgetown University. Formerly an atheist, Hill came into communion with the Catholic Church in 2009. He recently responded to questions from Catholic World Report about what natural law is and is not, common objections to natural law, how natural law developed and how it has been undermined, loss of faith in God in the West and the decline of natural law, and his journey from atheism into the Catholic Church.

CWR: What, in a nutshell, is "natural law" and how has it developed from the classical era to today?

Dr. Hill: Natural law is the idea that the world is ordered in a certain way, morally and physically, and that we can draw practical conclusions about how to live based upon what we learn about this order. Natural law means that there are objective moral truths built right into the fabric of the natural world. It means that things work in a particular way because they have been designed with a specific purpose. It means that there are better and worse ways for human beings, individually and collectively, to live.

The greatest of all natural law thinkers, Thomas Aquinas, argued that the natural law is not only “out there” in the world—a set of binding norms that govern us—but is “in here.” We human beings have the natural law built right into us. We have within us, in an inchoate way, a moral template for the development of our conscience—Aquinas called this “synderesis”—which, under proper social conditions, unfolds our moral sense of right and wrong. And even our natural desires are “ordered to the good.” Aquinas’s natural law theory holds that, when human beings are properly educated, we naturally develop into fully-functioning human beings. So, natural law implies that, by following this order, we achieve fulfillment and happiness.

The natural law tradition developed over the course of some two thousand years. It began with the insights of pre-Christian thinkers including Plato, Aristotle and the Stoics. But it was fashioned into a workable system by Christian thinkers, especially Thomas Aquinas in the thirteenth century.

In some ways, our moral and political system is still based on the natural law but we have, since about the eighteenth century, become, as a civilization, intellectually estranged from the natural law tradition. Some of the reasons for this are discussed below.

CWR: What are some of the common objections to natural law today?

Dr. Hill: There are at least two objections that have been continually restated throughout history by those skeptical of the natural law. They are, in a sense, contrary objections. The first misunderstands the idea of “law” while the second misconstrues what we mean by “natural.”

The first objection is that natural law cannot be true because, when we look around the world at the moral outlook of different cultures now and throughout history, we find a dizzying variety of practices and opinions on such things as abortion, infanticide, homosexuality, etc. This lack of moral uniformity indicates, according to skeptics, that there cannot be a natural law “written on the hearts” of men. If there were, and if it were obvious, there would be much more uniformity of judgment in moral matters.

What this objection fails to account for is that human beings were made free—free even to depart from the natural law. And it fails to understand that we can, individually and collectively, “lose sight” of the law.

At the heart of this objection is the misconception that what the law requires will be so patently evident that all moral disagreements will disappear. But there are several problems with this. First, as Aristotle noted, ethical judgments (and practices) fall into the realm of phronesis, not sophia, i.e., practical, not theoretical wisdom. Even where two people may agree about general principles, there will frequently be disagreement about how to apply these principles on particular matters. Does the commandment, “Thout shall not kill” preclude capital punishment? It depends on whether the principle applies only to innocent persons or to those convicted of a crime. The point is, the closer we come to tangible, practical ethical reality, the more variability we should expect. One reason for this, by the way, is that the concrete conditions “on the ground” may require different applications for the same general principle. A culture with limited material resources may adopt different patterns of property ownership, for example, than a relatively wealthier society.

Finally, as Aquinas was well-aware, cultures and peoples frequently “get off the track.” Individuals can be poorly educated or improperly influenced by others and cultures can deteriorate morally—especially when cultures ignore or are skeptical of the existence of objective moral imperatives, as we see in western culture today.

In sum, the existence of the natural law does not ensure uniformity of judgment or practice.

The second and converse objection is that natural law means that whatever people do as a matter of course must be “natural.” Since people seem to “naturally” engage in activities traditionally condemned by the natural law—e.g. infanticide, homosexuality, drug taking—these activities must be “natural.” So, the objection goes, natural law ought to permit these acts, rather than condemn them.

The problem here is that the skeptic has a very different idea of “nature” and “natural” than that of followers of classical natural law theory. For the former, the “natural” is simply what we do. It is “doing what comes naturally,” as the saying goes. Natural law thinkers, however, hold that the “natural” is neither a purely static nor a purely descriptive idea. The “natural” is what we are at our best and most developed and fulfilled: it is what we do when we have approached achieving our telos. The natural, in sum, is what we ought to do, not what anyone does do. And this “ought” is at one with the kinds of actions that are best for us—that conduce to our happiness, well-being and spiritual development.

We can see from these two objections that the term “natural law” is almost an oxymoron for modern thinkers. It is a contradiction in terms because (to the contemporary mind) “law” is what we have to do while “natural” is what we want to do. One of the most important assumptions of natural law theory is that this dichotomy between duty and desire, social obligation and self-interest—the “is” and the “ought”—has been greatly exaggerated in modern philosophy and culture.

CWR: Since natural law is so closely associated with Christianity, notably with St. Thomas Aquinas among others, why would or should secular thinkers embrace or support it?

May 7, 2016

The Image of Man Has Been Raised Up: On the Feast of the Ascension of the Lord

"The Ascension" (1305) by Giotto [WikiArt.org]

by Carl E. Olson

"You ascended into glory, O Christ our God, and You delighted the disciples with the promise of the Holy Spirit. Through this blessing, they were assured that You are the Son of God, the Redeemer of the World."

—Troparion for the Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom, Feast of the Ascension of our Lord Jesus Christ

"Christ's Ascension is therefore not a spectacle for the disciples but an event into which they themselves are included. It is a sursum corda, a movement toward the above into which we are all called. It tells us that man can live toward the above, that he is capable of attaining heights. More: the altitude that alone is suited to the dimensions of being human is the altitude of God himself. Man can live at this height, and only from this height do we properly understand him. The image of man has been raised up, but we have the freedom to tear it down or to let ourselves be raised."

— Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, from Images of Hope: Meditations On Major Feasts (Ignatius Press, 2006)

Readings:

• Acts 1:1-11

• Psa. 47:2-3, 6-7, 8-9

• Eph. 1:17-23 or Heb. 9:24-28; 10:19-23

• Lk 24:46-53

"As he blessed them he parted from them and was taken up to heaven." (Lk 24:51)

With these simple, matter-of-fact words, Luke describes the Ascension of Jesus, expressed even more concisely in the Creed: "He ascended into heaven." This event is so important for Luke that the Acts of the Apostles opens with a description of the same event. As the disciples looked on, Luke records, Jesus "was lifted up, and a cloud took him from their sight" (Acts 1:9). Mark's account, heard today, is equally direct and succinct: "So then the Lord Jesus, after he spoke to them, was taken up into heaven and took his seat at the right hand of God" (Mk. 16:19).

This dramatic moment has been celebrated in the Church on the fortieth day after Easter since the earliest centuries. Some of the Church Fathers, including Augustine, said that the feast had been observed since the time of the apostles, although the earliest evidence of its celebration dates to the fifth century. In the Latin Rite in the United States the Feast of the Ascension is one of six solemnities, the others being the solemnities of Mary, Mother of God (January 1); the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary (August 15); All Saints (November 1), the Immaculate Conception (December 8), and the Nativity of Our Lord Jesus Christ (December 25).

Despite being a solemnity and a holy day of obligation, the Feast of the Ascension is sometimes completely overlooked or not given much attention. Ask Catholics what is the significance of the Feast and answers aren't always immediate. The rather mysterious nature of the Feast is heightened in some ecclesiastical provinces by its transference from the sixth Thursday of Easter to the following Sunday. In a way, the Solemnity bears a resemblance to the sacrament of Confirmation, the exact meaning of which is not always understood well and suffers for not being more clearly explained and comprehended.

This occasional murkiness is unfortunate because the Ascension is such a joyful event in the work and life of Jesus Christ, as well as being a vital reality in the ongoing life and mission of the Church. To appreciate this joy and vitality we should keep in mind what the Catechism of the Catholic Church states about the liturgical calendar: The Church, "in the course of the year, . . . unfolds the whole mystery of Christ from his Incarnation and Nativity through his Ascension, to Pentecost and the expectation of the blessed hope of the coming of the Lord" (CCC, 1194).

Hinted at here are revealing parallels between the Incarnation and the Ascension and between the Nativity and Pentecost. In the Incarnation the eternal Son of God took on human nature in order to save mankind. By the power of the Holy Spirit, divinity and humanity were united in one Person; the Word became flesh (Jn 1:14) and lowered Himself to the level of dust and death. The Nativity is the physical, outward revelation of this reality: the Christ Child is born and history and the world are never the same.

At the Ascension the crucified, risen Son of God returns to His Father. Having descended to dusty earth, He now returns to heavenly glory. Having conquered death, He ascends to eternal life. But He returns to the right hand of the Father not just as the Word, but as the Incarnate Word. The doors of heaven are now open and humanity can now approach the throne room of God, the way having been paved by the life, death, and resurrection of the God-man. Pentecost, finally, is the manifestation of the God-man's Church, which is both human and divine. The Church was revealed to the world on that day—fifty days after Easter—by the power of the Holy Spirit.

All of this theology is nice enough, but what does it mean for us? It means the Feast of the Ascension is a celebration of salvation won. The Catholic Encyclopedia notes that "in the Eastern Church this feast was known as analepsis, the taking up, and also as the episozomene, the salvation, denoting that by ascending into His glory Christ completed the work of our redemption." The tendency is often to think of the Resurrection as the culmination of Jesus' salvific work, but it is the Ascension that places the final stamp of approval on the sacrificial and victorious work of our Savior. This is beautifully expressed in the first chapter of Paul's epistle to the Ephesians:

May the eyes of your hearts be enlightened, that you may know what is the hope that belongs to his call, what are the riches of glory in his inheritance among the holy ones, and what is the surpassing greatness of his power for us who believe, in accord with the exercise of his great might: which he worked in Christ, raising him from the dead and seating him at his right hand in the heavens ... (Eph. 1:17-20).

Now that the Incarnate Son of God has ascended into heaven and sits in the throne room of God, mankind can follow. United to the Son through baptism and deepening communion with Him through reception of the Holy Eucharist and the other sacraments, the hope of heaven is ours.

"The ascension of Christ is our elevation," declared Leo the Great in a sermon on the Ascension, "Hope for the body is also invited where the glory of the Head preceded us. Let us exult, dearly beloved, with worthy joy and be glad with a holy thanksgiving. Today we not only are established as possessors of paradise, but we have even penetrated the heights of the heavens in Christ." Where the sin of the first Adam closed the gates of Paradise, the righteousness of the new Adam has opened them wide.

Jesus promised His disciples that He would prepare a place for them (Jn. 14). Because of the Ascension, we know He has prepared a place for those who are His. Because of the Ascension, we have the hope of His return and of our future passage into glory. "The Ascension, then," Pope John Paul II explained in May 2000, "is a Trinitarian epiphany which indicates the goal to which personal and universal history is hastening. Even if our mortal body dissolves into the dust of the earth, our whole redeemed self is directed on high to God, following Christ as our guide."

Our Guide has come, died, rose from the dead, and ascended into heaven. Let us celebrate the Feast!

(This article was originally published in 2004 in Our Sunday Visitor in a slightly different form.)

May 3, 2016

Tradition: Its Necessity and Its Discontents

A family prays together before a meal at their Chicago home in this 2012 file photo. (CNS photo/Karen Callaway, Catholic New World)

Tradition: Its Necessity and Its Discontents | James Kalb | CWR

Man is social, cultural, and rational, and acts in accordance with (mostly implicit) principles and ideals. For that reason tradition is directed toward something higher than itself.

I noted last month that living well is difficult apart from a definite and well-developed tradition of life. Otherwise we simply won't know what we're doing, and we'll have to make up everything as we go along without any idea of ultimate results or significance, or of what we might be missing.

Such claims for the necessity of tradition make no sense to many people today.

One objection is that they are meaningless, since everything people do is part of a tradition. There is Catholic tradition, Mafia tradition, Buddhist tradition, Bolshevik tradition, anarchist tradition, and so on. So praising tradition tells us nothing about what anyone should do.

Another is that it's the genius of tradition to develop, so a break in tradition can better be seen as a variation or new development. If people are starting to do something, it's part of their tradition as it now exists. And besides, traditions are complex, as complex as the situations they deal with. In a Catholic society there are likely to be traditions of devotion, orthodoxy, and rigor, but also of laxness, skepticism, heresy, atheism, and criminality. Much the same applies to other communities, so why pick out some tendencies within a community's overall tradition of life and call them the tradition of the community to the exclusion of all others? Don't all the parts come together to make up the whole?

A different sort of objection is based on liberal individualism. I have my life, and I'm responsible for it, so why should I give special preference to what some restricted group of people did in the past? Why wouldn't it be better to choose freely from all the possibilities offered by human thought and experience, or decide on some new departure if that seems better? That's what founders of traditions do, and traditionalists don't complain about them, so why shouldn't I have the same privilege?

A related objection has to do with pluralism. In modern society there are a variety of traditions present, and it would be unfair, discriminatory, and divisive to deny any of them equal status. That's why we're told we need to celebrate diversity and be careful to include equally those who are different. But if we do that each tradition will be deprived of authority, even informal authority, in anything that matters to other people. Otherwise, some people will be marginalized. So traditions can't have authority that matters socially, which means they can't exist as traditions but only as collections of optional private opinions and practices.

And then there's the practical problem of how people live today. Life has changed, so why should old habits and attitudes still make sense?

Carl E. Olson's Blog

- Carl E. Olson's profile

- 20 followers