Carl E. Olson's Blog, page 18

April 4, 2016

Regensburg Revisited: Ten Years Later, A West Still in Denial

Pope Benedict XVI waves to pilgrims after a 2006 Mass on Islinger Field near Regensburg, Germany. (CNS photo/Kai Pfaffenbach, Reuters)

Regensburg Revisited: Ten Years Later, A West Still in Denial | Dr. Samuel Gregg | CWR

Irrationality not only manifests itself in violence but also in an inability to apply authentic reason to the many pressing challenges of our age.

A decade ago, a 79 year-old soft-spoken, white-haired German theologian returned to visit a university at which he had spent much of his academic career. On such occasions, it’s not unusual for a distinguished professor-emeritus to offer some formal remarks. Such reflections rarely receive much attention, and are often seen as exercises in reminiscing by scholars whose most substantial achievements are behind them.

In this instance, however, the speech delivered at the University of Regensburg on 12 September 2006 by the theologian Joseph Ratzinger, better known as Pope Benedict XVI, had immediate global impact. For weeks, even months afterwards, newspapers, magazines, scholarly journals, and even entire books attacked, defended, and analyzed the almost 4,000 words which came to be known as the Regensburg Address. Copies of the text and effigies of its author, however, were also ripped up, trampled on, and publicly burnt throughout the Islamic world. Television screens were dominated by images of enraged Muslim mobs and passionate denunciations by Muslim leaders, most of whom had clearly not read the text.

Also noticeable, however, was the frosty reception accorded to Pope Benedict’s remarks in much of the West. Descriptions such as “provocative,” “ill-timed,” “insensitive,” “un-feeling,” and “undiplomatic” appeared in religious and secular media outlets. Certainly the Pope had plenty of vocal defenders in North America and Europe. Among other things, they suggested that some Muslims’ frenzied reaction to the Regensburg Address proved that Benedict’s gentle query about the place of reason in Islamic belief and practice was dead on-target.

Yet there’s no doubt that Benedict’s words at Regensburg touched a nerve—perhaps even several nerves—in the Western world. For while the Regensburg Address received so much attention because of nine paragraphs in which Benedict analyzed a fourteenth-century exchange between a Byzantine Emperor and his Persian Muslim interlocutor, the text’s primary focus concerned deep problems of faith and reason that characterize the West and Christianity today. And many of these pathologies quickly surface whenever and wherever Islamist terrorism rears its head. They continue to enfeeble the West’s response to people whose acts in locations ranging from Brussels to Paris, Beirut to Jakarta, Jerusalem to San Bernardino, Abuja to London, and Lahore to New York reflect many things, including a particular understanding of the nature of the Divine.

The West contra Logos

One of the basic theses presented by Benedict at Regensburg was that how we understand God’s nature has implications for whether we can judge particular human choices and actions to be unreasonable. Thus, if reason is simply not part of Islam’s conception of the Divinity’s nature, then Allah can command his followers to make unreasonable choices, and all his followers can do is submit to a Divine Will that operates beyond the categories of reason.

Most commentators on the Regensburg Address did not, however, observe that the Pope declined to proceed to engage in a detailed analysis of why and how such a conception of God may have affected Islamic theology and Islamic practice. Nor did he explore the mindset of those Muslims who invoke Allah to justify jihadist violence. Instead, Benedict immediately pivoted to discussing the place of reason in Christianity and Western culture more generally. In fact, in the speech’s very last paragraph, Benedict called upon his audience “to rediscover” the “great logos”: “this breadth of reason” which, he maintained, orthodox Christianity has always regarded as a prominent feature of God’s nature. The pope’s use of the word “rediscover” indicated that something had been lost and that much of the West and the Christian world had themselves fallen into the grip of other forms of un-reason. Irrationality can, after all, manifest itself in expressions other than mindless violence.

That irrationality is loose and ravaging much of the West—especially in those institutions which are supposed to be temples of reason, i.e., universities—is hard to deny.

April 3, 2016

Divine Mercy Sunday: Preparation, Proclamation, Perseverance, and Purpose

Divine Mercy Sunday: Preparation, Proclamation, Perseverance, and Purpose | Carl E. Olson | On the Readings for Sunday, April 3, 2016

Readings:

• Acts 5:12-16

• Ps 118:2-4, 13-15, 22-24

• Rev 1:9-11a, 12-13, 17-19

• Jn 20:19-31

It is fitting that on this second Sunday of Easter, decreed in 2000 by Pope John Paul II to be Divine Mercy Sunday, that the readings provide a biblical blueprint of how divine mercy and grace would spread in the months and years immediately following the Resurrection.

During the Easter season, leading up to the great Feast of Pentecost, readings from the Acts of the Apostles take the place of Old Testament readings. In this way the connection between “all that Jesus did and taught” (Acts 1:1) and all that the apostles did and taught can be clearly seen and reflected upon. The Evangelist Luke portrayed Jesus as The Prophet who would do great signs and wonders (the greatest being His death and resurrection) and in the Acts of the Apostles he depicted the early Christians—especially the apostles Peter and Paul—as doing “many signs and wonders among the people” (Acts 5:12).

The blueprint of mercy can be summed up in four words: preparation, proclamation, perseverance, and purpose.

The preparation began during the ministry of Jesus, as He spent countless hours, days, and months with His disciples, teaching them by both word and example. Christ’s Passion and the Resurrection took that preparation to a place the disciples could barely begin to fathom prior to those dramatic events. Today’s Gospel reading highlights, in the well-known story of doubting Thomas, that the process of preparation was not a quick or easy one. As the disciples hid behind closed doors, they were often filled with fear and confusion. But the appearance of the Risen Christ in their midst was a source of peace and joy. And so they received their instructions: “As the Father has sent me, so I send you.” Then, later, in response to Thomas’s famous cry—“My Lord and my God!”—Jesus further prepared the disciples for their divine mission by pointing them toward the many souls in need of the Gospel: “Blessed are those who have not seen and have believed.”

The proclamation of that Gospel is seen all through Acts, including in today’s reading. The signs and wonders performed by Christ were soon being performed by the leaders of His Body, the Church, and that Body grew quickly. Luke emphasized the “signs and wonders” throughout his Gospel to present Jesus as the New Moses. Those marks of prophetic activity are mentioned many times in Acts, notably in Peter’s sermon on Pentecost and his recitation of the prophet Joel (2:17-22), and in today’s reading, which describes the proclamation of God’s word by the apostles (cf., 4:29-30), especially the head apostle, Peter.

In addition to Acts, the readings during Easter include selections from the final book of the Bible, the Revelation of Jesus Christ. One reason is to show the perseverance of the early Christians—including the author, John—in the face of persecution. John the Revelator referred to both when he wrote of the “endurance we have in Jesus”; he explained that he had been exiled to the island of Patmos (about 37 miles southwest of modern Turkey) “because I proclaimed God’s word and gave testimony to Jesus.” While celebrating the Lord’s Day—likely in the course of the Liturgy—John saw the risen and victorious Christ standing among the lamp stands, representing the Church. The Son of Man, “the first and the last,” assures John that the perseverance of the saints is not in vain, but will be rewarded by eternal life: “Once I was dead, but now I am alive forever and ever.”

We return to today’s Gospel to find a perfect summation of the purpose of these many actions of preparation, proclamation, and perseverance. John explained that much more could have been written about Jesus in his Gospel, but that “these are written that you may come to believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God, and that through this belief you may have life in his name.” By God’s mercy and grace, may we believe more deeply and experience more fully the life of the Risen Lord!

(This "Opening the Word" column originally appeared in the April 15, 2007, issue of Our Sunday Visitor newspaper.)

March 31, 2016

New: "God So Loved the World" by Fr. Robert Spitzer, SJ

Now available from Ignatius Press:

God So Loved the World: Clues to Our Transcendent Destiny from the Revelation of Jesus

by Fr. Robert Spitzer, SJ

In this volume the brilliant Fr. Spitzer probes in detail the major question that if an intelligent Creator God – manifest in logical proofs, scientific evidence, and near death experiences - who is the source of our desire for the sacred, and the transcendental desires for truth, love, goodness, and beauty, would want to reveal himself to us personally and ultimately.

He then shows this is reasonable not only in light of our interior experience of a transcendent Reality, but also that a completely intelligent Reality is completely positive--implying its possession of a completely positive virtue – namely "love", defined as agape.

This leads to the question whether God might be unconditionally loving, and if he is, whether he would want to make a personal appearance to us in a perfect act of empathy – face to face. After examining the rational evidence for this, he reviews all world religions to see if there is one that reveals such a God – an unconditionally loving God who would want to be with us in perfect empathy. This leads us to the extraordinary claim of Jesus Christ who taught that God is "Abba", the unconditionally loving Father.

Jesus' claims go further, saying that He is also unconditional love, and that his mission is to give us that love through an act of complete self-sacrifice. He also claims to be the exclusive Son of the Father, sent by God to save the world, and the one who possesses divine power and authority. The rest of the book does an in-depth examination of the evidence for Jesus' unconditional love of sinners, his teachings, his miracles, and his rising from the dead. As well as the evidence for Jesus' gift of the Holy Spirit that enabled his disciples to perform miracles in his name, and evidence for the presence of the Holy Spirit today.

If this strong evidence convinces us to believe that Jesus is our ultimate meaning and destiny, and desire His saving presence in our lives, that evidence should galvanize the Holy Spirit within us to show that Jesus is Lord and Savior, "the way, the truth, and the life." And our faith in him will transform everything we think about our nature, dignity, and destiny– and how we live, endure suffering, contend with evil, and treat our neighbor.

Fr. Robert Spitzer, SJ,is a philosopher, educator, author and former President of Gonzaga University. He is founder and President of the Magis Institute, dedicated to public education on the relationship among the disciplines of physics, philosophy, reason, and faith. He is the head of the Ethics and Performance Institute which delivers web-based ethics education to corporations, and he is also President of the Spitzer Center of Ethical Leadership, which delivers similar curricula to non-profit organizations. His other books include Finding True Happiness, The Soul's Upward Yearning and Healing the Culture.

March 29, 2016

New Ignatius Press novel Barely a Crime “is what all first-rate thrillers should be...."

"... terrifying, fast-paced and impossible to put down”

San Francisco, March 29, 2016 – In this new gripping thriller by novelist Robert Ovies, Barely a Crime , two men from the Northern Irish underworld are recruited by an enigmatic stranger for a shadowy operation. Promising to make them very rich without involving them in theft or murder, the job seems too good to be true; in fact, it seems to be barely a crime.

, two men from the Northern Irish underworld are recruited by an enigmatic stranger for a shadowy operation. Promising to make them very rich without involving them in theft or murder, the job seems too good to be true; in fact, it seems to be barely a crime.

When Crawl and Kieran discover the identity of the man who has hired them for the break-in of the century, they realize they might be involving themselves in a high-stakes technological breakthrough, leading them to devise a scheme for demanding a bigger payout. As the law of unintended consequences kicks in, so do life-and-death consequences, not only for themselves, not only for many others, but for the whole world.

When asked if the novel addressed any particularly significant contemporary issue, author Robert Ovies answered, “If Barely a Crime has a moral, I’d vote for: ‘Trying to play God is a dangerous, dangerous game.’”

Piers Paul Read, author of The Death of a Pope, says, “Based on an intriguing premise, Barely a Crime holds the reader from start to finish.”

“Ovies paints a disturbingly compelling snapshot of a criminal underworld. With a strong narrative replete with startling twists and turns, a taut plot and believable characters, Barely a Crime is what all first-rate thrillers should be: terrifying, fast-paced and impossible to put down,” explains Fiorella de Maria, author of Do No Harm.

Lucy Beckett, author of A Postcard from the Volcano, says, “Robert Ovies is an excellent thriller writer. Barely a Crime moves at a cracking pace, has a complicated and ingenious plot and sustains tension through some hair-raising scenes. A gripping read, with a thoroughly scary scientific fantasy at its core.”

“Barely a Crime is Christ-haunted in the same manner that the novels and stories of Flannery O'Connor are, and it is a gripping and cliff-hanging story, glowing with doom-laden gravitas in the gloom of sin and prideful passion,” says Joseph Pearce, author of Catholic Literary Giants.

“From the very beginning this book will grab you by the lapel and drag you into a story of thrilling mystery, madness and thought-provoking grace. It weaves a tale of incremental depravity and redemption with characters who struggle to escape the impetus of their wounded past, and the fears, doubts and latent anger that has come to define them,” says Michael Richards, author of Tobit’s Dog.

About the Author:

Robert Ovies, a former advertising executive, is a Catholic deacon. He has a master’s in social work, and with his wife he served as a mission worker on Arizona’s Navajo Reservation. For ten years, they were live-in directors of a communal halfway house in the Detroit area. His first novel was The Rising.

Robert Ovies, the author of Barely a Crime, is available for interviews about this book.

To request a review copy or an interview with Robert Ovies, please contact:

Rose Trabbic, Publicist, Ignatius Press at (239) 867-4180 or rose@ignatius.com

Product Facts:

Title: BARELY A CRIME

A Novel

Editor: Robert Ovies

Release Date: March 2016

Length: 222 pages

Price: $15.95

ISBN: 978-1-62164-089-9 • Softcover

Order: 1-800-651-1531 • www.ignatius.com

Mother Angelica: America’s Nun

Mother Angelica, founder of the Eternal Word Television Network, is pictured in a 1992 photo. She died March 27 at the Poor Clares of Perpetual Adoration monastery in Hanceville, Ala. She was 92. (CNS files)

Mother Angelica: America’s Nun | Paul Kengor | CWR's The Dispatch

If we’re looking for the most influential American Catholic at the turn of the century, and at least into the young 21st century, male or female, I would vote for Mother Angelica.

The first time I encountered the unforgettable person of Mother Angelica was the mid-1990s. I was in graduate school, a former Catholic-turned-agnostic, but searching. I was coming back to the Catholic faith, it would turn out, but first through the arms of Protestant Evangelicalism.

Whether in my car or living room, I would flip through the channels on my radio or TV in search for Christian programming. As for the radio, there were no Catholic stations. Not one. They were all “Christian” stations, meaning Evangelical. As for TV, there were, much like still today, “Christian” stations comprised of a vague Protestant programming, most of it very poor quality and extremely loose theology—often wild, embarrassing, and thoroughly unconvincing (if not repellent) to a skeptic searching for answers. In fact, to this day, when you check your DirecTV or Dish Network guide, you can find a half-dozen or so such stations (all non-Catholic), which my Protestant friends and colleagues are embarrassed by.

And then one day I found Mother Angelica on my TV. She had a strikingly blue-collar style, reminding me of my Western Pennsylvania/Italian family roots. That was fitting, really, since she was raised not too far from me. I’ve driven through her so-called Akron-Canton region many times. This folksy nun from the town that houses the NFL Hall of Fame was tough. She was no sophisticate. That wasn’t her desire or approach—quite the contrary. That’s a bit ironic, because the television and larger media network that she was growing is today very sophisticated. The EWTN media conglomerate is distinctly theological, thoughtful, orthodox, polished, high-brow—from the TV channel to the mass network of radio affiliates, which I can pick up in the car almost anywhere, or via Sirius radio, my computer, and my phone.

That was what this little nun from Canton bequeathed. And it is no small achievement.

Today, I watch EWTN television more than any other channel.

March 28, 2016

The Spiritual Legacy of Mother Angelica

Mother Angelica, founder of Eternal Word Television Network, died at age 92 March 27 at the Poor Clares of Perpetual Adoration monastery in Hanceville, Ala. She is pictured in an undated photo. (CNS photo/courtesy EWTN)

The Spiritual Legacy of Mother Angelica | Bishop Robert Barron | Catholic World Report

While the critics of the founder of Eternal Word Television Network have largely faded away, the impact and influence of the nun from Canton, Ohio are incontestable.

Mother Angelica, one of the most significant figures in the post-conciliar Catholic Church in America, has died after a fourteen-year struggle with the after effects of a stroke. I can attest that, in "fashionable" Catholic circles during the eighties and nineties of the last century, it was almost de rigueur to make fun of Mother Angelica. She was a crude popularizer, an opponent of Vatican II, an arch-conservative, a culture-warrior, etc., etc. And yet while her critics have largely faded away, her impact and influence are incontestable. Against all odds and expectations, she created an evangelical vehicle without equal in the history of the Catholic Church. Starting from, quite literally, a garage in Alabama, EWTN now reaches 230 million homes in over 140 countries around the world. With the possible exception of John Paul II himself, she was the most watched and most effective Catholic evangelizer of the last fifty years.

Read Raymond Arroyo's splendid biography in order to get the full story of how Rita Rizzo, born and raised in a tough neighborhood in Canton, Ohio, came in time to be a nun, a foundress, and a television personality. For the purposes of this brief article, I would like simply to draw attention to three areas of particular spiritual importance in the life of Mother Angelica: her trust in God's providence, her keen sense of the supernatural quality of religion, and her conviction that suffering is of salvific value.

The accounts of the beginning of EWTN read like the stories of some of the great saintly founders of movements and orders within the Church. Mother had a blithe confidence that if God called her to do something, he would provide what was needed.

March 27, 2016

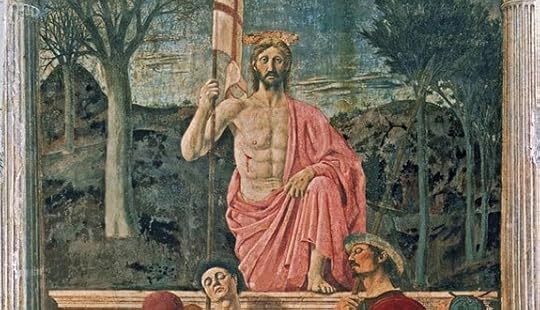

In His Rising is Our Hope: Art and the Resurrection

Detail from “Resurrection” (c. 1460) by Piero della Francesca (WikiArt.org)

In His Rising is Our Hope | Sandra Miesel | Catholic World Report

A short history of how Christians throughout the ages have depicted the mysterious and transforming event of the Resurrection of Jesus Christ.

In him, who rose from the dead,

our hope of resurrection dawned.

The sadness of death gives way

to the bright promise of immortality.

— Preface for Christian Death I

Sacred images do not instantly spring from the pages of Scripture to gauzy forms on gilt-edged holy cards. Traditional Christian art, like Christian theology, developed slowly as the Church’s understanding of the Gospel deepened and the cultures around her shifted. For instance, today’s Catholics probably picture our newly Risen Savior as nude save for a fluttering wrap and carrying a banner blazoned with the cross. Such an image would have shocked ancient Christians. Although well aware that “If Christ has not been raised…faith is futile” (1 Cor 15: 17), they did not try to represent that rising. Artists experimented for centuries to find appropriate ways to depict the climax of Our Lord’s redemptive work.

The Gospels are silent about the exact moment when Jesus was restored to new life. Instead they give four unique accounts of holy women and apostles finding the tomb empty on Easter morning (Mt 28:1-10, Mk 16:1-8, Lk 24:1-12, Jn 20:1-18). Afterwards, the risen Christ appears to his followers with convincing proofs of his identity: his transformed body is still his own body, neither a delusion nor a ghost.

Early Christian artists did not presume to supplement Scripture. Perhaps they feared to invade God’s privacy, as it were. Rather than attempt direct illustration of Our Lord’s emergence from the tomb, they painted catacombs and sculpted tombs with scenes from the Book of Jonah. Jesus himself had used the Sign of Jonah as a veiled prophecy of his death and resurrection (Mt 12:40). As the prophet spent three days inside the whale, so would the Son of Man spend three days buried in the earth.

Another way to avoid the delicate moment when Jesus rose was to replace his figure with his cross-shaped standard that bears a Chi-Rho within a victory wreath. This is planted between the grave guards on Roman sarcophagus carvings of the fourth century. The same tactic was applied to early Crucifixion scenes: a sign takes the place of physical reality.

But Christ’s sepulcher itself became the preferred element in depictions of Easter. The oldest known example of this image was painted about 230 AD on the baptistery wall of a church in the Syrian town of Dura-Europos. Here the three “Myrrh-Bearing Women” bring spices to anoint Jesus (Mk 16:1). They approach a huge, plain sarcophagus, not the hollow rock chamber that the Gospels describe. The empty tomb was an appropriate—and popular—baptismal motif because receiving the sacrament is a spiritual dying and rising with Christ (Rom 6:3-4).

Coincidentally, a mural of Ezekiel’s vision of the dry bones reanimating (Ez 37:1-14) adorned the synagogue in the same town. Christians had inherited the Jewish belief in a general resurrection of the dead at the end of time attested by Mary of Bethany before the raising of her brother Lazarus (Jn 11:24). As a creature of body and soul, mortal man will need both reunited to participate fully in the life of the world to come. Human resurrections, past and future, often complement the Resurrection of Jesus in Christian art.

A century after those murals appeared in Dura-Europos, the Emperor Constantine aligned himself with Christianity and built churches over sacred sites all over the empire. Among these was the Anastasis Rotunda in Jerusalem, begun in 337 AD. Its conical canopy sheltering the tomb of Christ influenced later depictions of the Easter tomb. For instance, it appears on a Roman ivory plaque made circa 420 AD as part of a small box. (Another side of the box has the earliest known Crucifixion scene.) Here one door of the elaborate open tomb depicts the Raising of Lazarus and a mourning woman. As in Mt 28:1, 4, two holy women and two stupefied soldiers flank the tomb.

More elements were added to Resurrection scenes: angels, extra guards, women prostrate before the Risen Lord. Subjects were combined to give a panorama of salvation that collapsed time and space. The Resurrection might be juxtaposed with the Crucifixion or Ascension or other biblical episodes.

Although the holy women at the empty tomb would long remain a popular image, by the end of the seventh century, the Church wanted to show Christ’s own victorious power in action. “Material figurations” were judged especially useful for forming faith in the Savior who was both True God and True Man. This new confidence in theology made visible also permitted artists to picture what preceded the Resurrection—death and entombment.

Thus arose a new visual formula called the Anastasis.

March 25, 2016

The Cross–For Us

The Cross–For Us | Hans Urs von Balthasar | An excerpt from A Short Primer For Unsettled Laymen

Without a doubt, at the center of the New Testament there stands the Cross, which receives its interpretation from the Resurrection.

The Passion narratives are the first pieces of the Gospels that were composed as a unity. In his preaching at Corinth, Paul initially wants to know  nothing but the Cross, which "destroys the wisdom of the wise and wrecks the understanding of those who understand", which "is a scandal to the Jews and foolishness to the gentiles". But "the foolishness of God is wiser than men, and the weakness of God is stronger than men" (I Cor 1:19, 23, 25).

nothing but the Cross, which "destroys the wisdom of the wise and wrecks the understanding of those who understand", which "is a scandal to the Jews and foolishness to the gentiles". But "the foolishness of God is wiser than men, and the weakness of God is stronger than men" (I Cor 1:19, 23, 25).

Whoever removes the Cross and its interpretation by the New Testament from the center, in order to replace it, for example, with the social commitment of Jesus to the oppressed as a new center, no longer stands in continuity with the apostolic faith. He does not see that God's commitment to the world is most absolute precisely at this point across a chasm.

It is certainly not surprising that the disciples were able to understand the meaning of the Cross only slowly, even after the Resurrection. The Lord himself gives a first catechetical instruction to the disciples at Emmaus by showing that this incomprehensible event is the fulfillment of what had been foretold and that the open question marks of the Old Testament find their solution only here (Lk 24:27).

Which riddles? Those of the Covenant between God and men in which the latter must necessarily fail again and again: who can be a match for God as a partner? Those of the many cultic sacrifices that in the end are still external to man while he himself cannot offer himself as a sacrifice. Those of the inscrutable meaning of suffering which can fall even, and especially, on the innocent, so that every proof that God rewards the good becomes void. Only at the outer periphery, as something that so far is completely sealed, appear the outlines of a figure in which the riddles might be solved.

This figure would be at once the completely kept and fulfilled Covenant, even far beyond Israel (Is 49:5-6), and the personified sacrifice in which at the same time the riddle of suffering, of being despised and rejected, becomes a light; for it happens as the vicarious suffering of the just for "the many" (Is 52:13-53:12). Nobody had understood the prophecy then, but in the light of the Cross and Resurrection of Jesus it became the most important key to the meaning of the apparently meaningless.

Did not Jesus himself use this key at the Last Supper in anticipation? "For you", "for the many", his Body is given up and his Blood is poured out. He himself, without a doubt, foreknew that his will to help these" people toward God who are so distant from God would at some point be taken terribly seriously, that he would suffer in their place through this distance from God, indeed this utmost darkness of God, in order to take it from them and to give them an inner share in his closeness to God. "I have a baptism to be baptized with, and how I am constrained until it is accomplished!" (Lk 12:50).

It stands as a dark cloud at the horizon of his active life; everything he does then-healing the sick, proclaiming the kingdom of God, driving out evil spirits by his good Spirit, forgiving sins-all of these partial engagements happen in the approach toward the one unconditional engagement.

As soon as the formula "for the many", "for you", "for us", is found, it resounds through all the writings of the New Testament; it is even present before anything is written down (cf. i Cor 15:3). Paul, Peter, John: everywhere the same light comes from the two little words.

What has happened? Light has for the first time penetrated into the closed dungeons of human and cosmic suffering and dying. Pain and death receive meaning.

Not only that, they can receive more meaning and bear more fruit than the greatest and most successful activity, a meaning not only for the one who suffers but precisely also for others, for the world as a whole. No religion had even approached this thought. [1] The great religions had mostly been ingenious methods of escaping suffering or of making it ineffective. The highest that was reached was voluntary death for the sake of justice: Socrates and his spiritualized heroism. The detached farewell discourses of the wise man in prison could be compared from afar to the wondrous farewell discourses of Christ.

But Socrates dies noble and transfigured; Christ must go out into the hellish darkness of godforsakenness, where he calls for the lost Father "with prayers and supplications, with loud cries and tears" (Heb 5:7). Why are such stories handed down? Why has the image of the hero, the martyr, thus been destroyed? It was "for us", "in our place".

One can ask endlessly how it is possible to take someone's place in this way. The only thing that helps us who are perplexed is the certainty of the original Church that this man belongs to God, that "he truly was God's Son", as the centurion acknowledges under the Cross, so that finally one has to render him homage in adoration as "my Lord and my God" Jn 20:28).

Every theology that begins to blink and stutter at this point and does not want to come out with the words of the Apostle Thomas or tinkers with them will not hold to the "for us". There is no intermediary between a man who is God and an ordinary mortal, and nobody will seriously hold the opinion that a man like us, be he ever so courageous and generous in giving himself, would be able to take upon himself the sin of another, let alone the sin of all. He can suffer death in the place of someone who is condemned to death. This would be generous, and it would spare the other person death at least for a time.

But what Christ did on the Cross was in no way intended to spare us death but rather to revalue death completely. In place of the "going down into the pit" of the Old Testament, it became "being in paradise tomorrow". Instead of fearing death as the final evil and begging God for a few more years of life, as the weeping king Hezekiah does, Paul would like most of all to die immediately in order "to be with the Lord" (Phil 1:23). Together with death, life is also revalued: "If we live, we live to the Lord; if we die, we die to the Lord" (Rom 14:8).

But the issue is not only life and death but our existence before God and our being judged by him. All of us were sinners before him and worthy of condemnation. But God "made the One who knew no sin to be sin, so that we might be justified through him in God's eyes" (2 Cor 5:21).

Only God in his absolute freedom can take hold of our finite freedom from within in such a way as to give it a direction toward him, an exit to him, when it was closed in on itself. This happened in virtue of the "wonderful exchange" between Christ and us: he experiences instead of us what distance from God is, so that we may become beloved and loving children of God instead of being his "enemies" (Rom 5:10).

Certainly God has the initiative in this reconciliation: he is the one who reconciles the world to himself in Christ. But one must not play this down (as famous theologians do) by saying that God is always the reconciled God anyway and merely manifests this state in a final way through the death of Christ. It is not clear how this could be the fitting and humanly intelligible form of such a manifestation.

No, the "wonderful exchange" on the Cross is the way by which God brings about reconciliation. It can only be a mutual reconciliation because God has long since been in a covenant with us. The mere forgiveness of God would not affect us in our alienation from God. Man must be represented in the making of the new treaty of peace, the "new and eternal covenant". He is represented because we have been taken over by the man Jesus Christ. When he "signs" this treaty in advance in the name of all of us, it suffices if we add our name under his now or, at the latest, when we die.

Of course, it would be meaningless to speak of the Cross without considering the other side, the Resurrection of the Crucified. "If Christ has not risen, then our preaching is nothing and also your faith is nothing; you are still in your sins and also those who have fallen asleep . . . are lost. If we are merely people who have put their whole hope in Christ in this life, then we are the most pitiful of all men" (I Cor 15:14, 17-19).

If one does away with the fact of the Resurrection, one also does away with the Cross, for both stand and fall together, and one would then have to find a new center for the whole message of the gospel. What would come to occupy this center is at best a mild father-god who is not affected by the terrible injustice in the world, or man in his morality and hope who must take care of his own redemption: "atheism in Christianity".

Endnotes:

[1] For what is meant here is something qualitatively completely different from the voluntary or involuntary scapegoats who offered themselves or were offered (e.g., in Hellas or Rome) for the city or for the fatherland to avert some catastrophe that threatened everyone.

Related IgnatiusInsight.com Articles:

• Jesus Is Catholic | Hans Urs von Balthasar

• Seeing Jesus in the Gospel of John | Excerpts from On The Way to Jesus Christ | Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger

• A Jesus Worth Dying For | Justin Nickelsen

• Encountering Christ in the Gospel | Excerpt from My Jesus | Christoph Cardinal Schönborn

• The Divinity of Christ | Peter Kreeft

• The Religion of Jesus | Blessed Columba Marmion | From Christ, The Ideal of the Priest

• Christ, the Priest, and Death to Sin | Blessed Columba Marmion | From Christ, The Ideal of the Priest

Hans Urs von Balthasar (1905-88) was a Swiss theologian, considered to one of the most important Catholic intellectuals and writers of the twentieth century. 2005 marks the centennial celebration of his birth.

Hans Urs von Balthasar (1905-88) was a Swiss theologian, considered to one of the most important Catholic intellectuals and writers of the twentieth century. 2005 marks the centennial celebration of his birth.

Incredibly prolific and diverse, he wrote over one hundred books and hundreds of articles. Read more about his life and work in the Author's Pages section of IgnatiusInsight.com.

The Spear that Truly Pierces the Heart

The Spear that Truly Pierces the Heart | George J. Galloway | CWR

To my mind, there are three great novels published during the last century-and-a-half depicting the Passion of Christ: Lew Wallace’s Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ (1880), Lloyd C. Douglas’ The Robe (1942), and Louis de Wohl’s classic The Spear (1955). All three books are compelling tales of the Christ and should be required reading for anyone interested in how the life of Jesus, both historically and spiritually, can be incorporated into our lives through a literary genre rarely and effectively used today.

They also depict the best fiction has to offer in page-turning suspense, despite the fact we all know what the outcome is. And this is the epitome of the craft of story-telling. Because these novels achieve the impossible: to keep you reading with twists and turns which challenge your faith, then reinvigorate it, and finally leave you with a strong yearning to act upon it. Unlike non-fiction, yarns and tales of ordinary and sometimes extraordinary characters can and do challenge the reader, because the reader can identify with their plight, perhaps their station in life, their problems and confusions, culminating in a shared experience of hope and redemption.

The Slave

All three novels are centered on enslavement. It’s hard for us to imagine today what it would be like to be a slave, even though slavery and indentured servitude were a sad yet important part of our history. We even ignore the very fact that slavery still exists in our world. Perhaps, we have been put to sleep; placated and distracted as we are by inane sit-coms, so-called “reality TV” shows, smart phones and sports. Very much like the mobs of Rome were tamed and assuaged by bloody gladiator contests, chariot races in the Coliseum, and given bread and wine for free, certainly an ominous precursor of a divine meal yet to come.

Louis de Wohl’s The Spear puts it right in our face.

March 24, 2016

The Easter Triduum: Entering into the Paschal Mystery

The Easter Triduum: Entering into the Paschal Mystery | Carl E. Olson

The liturgical year is a great and ongoing proclamation by the Church of the Gospel of Jesus Christ and a celebration of the Mystery of the Word. Through this yearly cycle, the Catechism of the Catholic Church explains, "the various aspects of the one Paschal mystery unfold"(CCC 1171). The Easter Triduum holds a special place in the liturgical year because it marks the culmination of the yearly celebration in proclaiming the Passion and Resurrection of Jesus Christ.

The Latin word triduum refers to a period of three days and has long been used to describe various three-day observances that prepared for a feast day through liturgy, prayer, and fasting. But it is most often used to describe the three days prior to the great feast of Easter: Holy Thursday, Good Friday, and Holy Saturday and the Easter Vigil. The General Norms for the Liturgical Year state that the Easter Triduum begins with the evening Mass of the Lord's Supper on Holy Thursday, "reaches its high point in the Easter Vigil, and closes with evening prayer on Easter Sunday" (par 19).

Just as Sunday is the high point of the week, Easter is the high point of the year. The meaning of the great feast is revealed and anticipated throughout the Triduum, which brings the people of God into contact – through liturgy, symbol, and sacrament – with the central events of the life of Christ: the Last Supper, His trial and crucifixion, His time in the tomb, and His Resurrection from the dead. In this way, "the mystery of the Resurrection, in which Christ crushed death, permeates with its powerful energy our old time, until all is subjected to him" (CCC 1169). During these three days of contemplation and anticipation the liturgies emphasize the sacrificial death of Christ on the Cross, and the sacraments of baptism and the Eucharist, by which the faithful enter into the life-giving Passion of Christ and grow in hope of eternal life in Him.

Holy Thursday | The Lord's Supper

The Triduum begins with the evening Mass of the Lord’s Supper on Holy Thursday, which commemorates when the Eucharist was instituted at the Last Supper by Jesus. The traditional English name for this day, "Maundy Thursday", comes from the Latin phrase Mandatum novum – "a new command" (or mandate) – which comes from Christ’s words: "A new commandment I give to you, that you love one another; even as I have loved you, that you also love one another" (Jn 13:34). The Gospel reading for the liturgy is from the first part of the same chapter and depicts Jesus washing the feet of the disciples, an act of servitude (commonly done by slaves or servants in ancient cultures) and great humility.

Earlier on Holy Thursday (or earlier in the week) the bishop celebrates the Chrism Mass, which focuses on the ordained priesthood and the public renewal by priests of their promises to faithfully fulfill their office. In the evening liturgy, the priest, who is persona Christi, will wash the feet of several parishioners, oftentimes catechumens and candidates who will be entering into full communion with the Church at Easter Vigil. In this way the many connections between the Eucharist, salvation, self-sacrifice, and service to others are brought together.

These realities are further anticipated in Jesus’ remark about the approaching betrayal by Judas: "Whoever has bathed has no need except to have his feet washed, for he is clean all over; so you are clean, but not all." The sacrificial nature of the Eucharist is brought out in the Old Testament reading, from Exodus 12, which recounts the first Passover and God’s command for the people of Israel, enslaved in Egypt, to kill a perfect lamb, eat it, and then spread its blood over the door as a sign of fidelity to the one, true God. Likewise, the reading from Paul’s epistle to the Christians in Corinth (1 Cor 11) repeats the words given by the Son of God to His apostles at the Last Supper: "This is my body that is for you. Do this in remembrance of me" and "This cup is the new covenant in my blood. Do this, as often as you drink it, in remembrance of me."

Thus, in this memorial of Jesus’ last meal with His disciples, the faithful are reminded of the everlasting value of that meal, the gift of the priesthood, the grave dangers of turning away from God, the necessity of the approaching Cross, and the abiding love that the Lord has for His people.

Good Friday | Veneration of the Cross

This is the first full day of the Easter Triduum, a day commemorating the Passion, Cross, and death of Jesus Christ, and therefore a day of strict fasting. The liturgy is profoundly austere, perhaps the most simple and stark liturgy of the entire year. The liturgy of the Lord’s Passion consists of three parts: the liturgy of the Word, the veneration of the Cross, and the reception of Communion. Although Communion is given and received, this liturgy is not a Mass; this practice dates back to the earliest years of the Church and is meant to emphasize the somber, mournful character of the day. The Body of Christ that is received by the faithful on Good Friday was consecrated the prior evening at the Mass of the Lord’s Supper and, in most cases, was adored until midnight or another late hour.

The liturgy of the Word begins with silence. After a prayer, there are readings from Isaiah 52 and 53 (about the suffering Servant), Psalm 31 (a great Messianic psalm), and the epistle to the Hebrews (about Christ the new and eternal high priest). Each of these readings draws out the mystery of the suffering Messiah who conquers through death and who is revealed through what seemingly destroys Him. Then the Passion from the Gospel of John (18:1-19:42) is proclaimed, often by several different lectors reading respective parts (Jesus, the guards, Peter, Caiaphas the high priest, Pilate, the soldiers). In this reading the great drama of the Passion unfolds, with Jew and Gentile, male and female, and the powerful and the weak all revealed for who they are and how their choices to follow or deny Christ will affect their lives and the lives of others.

The simple, direct form of the Good Friday liturgy and readings brings the faithful face to face with the cross, the great scandal and paradox of Christianity. The cross is solemnly venerated after intercessory prayers are offered for the world and for all people. The deacon (or another minister) brings out the veiled cross in procession. The priest takes the cross, stands with it in front of the altar and faces the people, then uncovers the upper part of the cross, the right arm of the cross, and then the entire cross. As he unveils each part, he sings, "This is the wood of the cross." He places the cross and then venerates it; other clergy, lay ministers, and the faithful then approach and venerate the cross by touching or kissing it. In this way each person acknowledges the instrument of Christ’s death and publicly demonstrates their willingness to take up their cross and follow Christ, regardless of what trials and sufferings it might involve.

Afterward, the faithful receive Communion and then depart silently. In the Byzantine rite, Communion is not even offered on this day. At Vespers a "shroud" bearing a painting of the lifeless Christ is carried in a burial procession, and the faithful keep vigil before it through the night.

Holy Saturday and Easter Vigil | The Mother of All Vigils

The ancient Church celebrated Holy Saturday with strict fasting in preparation of the celebration of Easter. After sundown the Christians would hold an all-night vigil, which concluded with baptism and Eucharist at the break of dawn. The same idea (if not the identical timeline) is found in the Easter Vigil today, which is the high point of the Easter Triduum and is filled with an abundance of readings, symbols, ceremony, and sacraments.

The Easter Vigil, the Church states, ranks "the mother of all vigils" (General Norms, 21). Being a vigil – a time of anticipation and preparation – it takes place at night, starting after nightfall and finishing before daybreak on Easter, thus beginning and ending in darkness. It consists of four general parts: the Service of Light, the Liturgy of the Word, Christian Initiation, and Liturgy of the Eucharist.

The Service of Light begins outdoors (or in a space outside of the main sanctuary) and in darkness. A fire is lit and blessed, and then the Paschal candle, which symbolizes the light of Christ, is lit from the fire by the priest, who proclaims: "May the light of Christ, rising in glory, dispel the darkness of our hearts and minds." The biblical themes of light removing darkness and life overcoming death suffuse the entire Vigil. The Paschal candle will be placed in the sanctuary (usually by the altar) for the Easter season, then will be kept in the baptistery so that when the sacrament of baptism is administered the candles of the baptized can be lit from it.

The faithful then join in procession back to the main sanctuary. The deacon (or priest, if no deacon is present), carries the Paschal Candle, lifting it three different times and chanting: "Christ our Light!" The people respond by singing, "Thanks be to God!" Everyone’s candles are lit from the Paschal candle and the faithful return in procession into the sanctuary. Then the Exultet is sung by the deacon (or priest or cantor). This is an ancient and beautiful poetic hymn of praise to God for the light of the Paschal candle. It may be as old as Saint Ambrose (d. 397) and has been part of the Roman tradition since the ninth century. In the darkness of the church, lit only by candles, the faithful listen to the song of light and glory:

Rejoice, O earth, in shining splendor,

radiant in the brightness of your King!

Christ has conquered! Glory fills you!

Darkness vanishes for ever!

And, concluding:

May the Morning Star which never sets

find this flame still burning:

Christ, that Morning Star,

who came back from the dead,

and shed his peaceful light on all mankind,

your Son, who lives and reigns for ever and ever. Amen.

The Liturgy of the Word follows, consisting of seven readings from the Old Testament and two from the New Testament. These readings include the story of creation (Genesis 1 and 2), Abraham and Isaac (Genesis 22), the crossing of the Red Sea (Exodus 14 and 15), the prophet Isaiah proclaiming God’s love (Isaiah 54), Isaiah’s exhortation to seek God (Isaiah 55), a passage from Baruch about the glory of God (Baruch 3 and 4), a prophecy of Ezekiel (Ezekiel 36), Saint Paul on being baptized into Jesus Christ (Rom 6), and the Gospel of Luke about the empty tomb discovered on Easter morning (Luke 24:1-21).

These readings constitute an overview of salvation history and God’s various interventions into time and space, beginning with Creation and concluding with the angel telling Mary Magdalene and others that Jesus is no longer dead; "You seek Jesus of Nazareth, the crucified. He has been raised; he is not here." Through these readings "the Lord ‘beginning with Moses and all the prophets’ (Lk 24.27, 44-45) meets us once again on our journey and, opening up our minds and hearts, prepares us to share in the breaking of the bread and the drinking of the cup" (General Norms, 11).

Some of the readings are focused on baptism, that sacrament which brings man into saving communion with God’s divine life. Consider, for example, Saint Paul’s remarks in Romans 6: "We were indeed buried with him through baptism into death, so that, just as Christ was raised from the dead by the glory of the Father, we too might live in newness of life." Easter is in many ways the season of baptism, the sacrament of Christian initiation, in which those who formally lived in darkness and death are buried and baptized in Christ, emerging filled with light and life.

From the early days of the ancient Church the Easter Vigil has been the time for adult converts to be baptized and enter the Church. After the conclusion of the Liturgy of the Word, catechumens (those who have never been baptized) and candidates (those who have been baptized in a non-Catholic Christian denomination) are initiated into the Church by (respectively) baptism and confirmation. The faithful are sprinkled with holy water and renew their baptismal vows. Then all adult candidates are confirmed and general intercessions are stated. The Easter Vigil concludes with the Liturgy of the Eucharist and the reception of the Body, Blood, Soul, and Divinity of the Crucified and Risen Lord. For as Eastern Catholics sing hundreds of times during the Paschal season, "Christ is risen from the dead; by death He conquered death, and to those in the graves, He granted life!"

(This article was originally published in a slightly different form in the April 9, 2006, edition of Our Sunday Visitor newspaper.)

Carl E. Olson's Blog

- Carl E. Olson's profile

- 20 followers