Lord, Not Legend: A Review of Brant Pitre’s "The Case for Jesus"

Lord, Not Legend: A Review of Brant Pitre’s

The Case for Jesus |

Dr. Leroy Huizenga | Catholic World Report

The new book by a notable young Scripture scholar addresses both the dominant paradigm in academic biblical studies and the more popular errors about Jesus and the New Testament.

A Tale of Two Paradigms

The dominant paradigm reigning in academic biblical studies today is marked by radical discontinuity. That’s why people who know the basics of the Christian story—whether they believe it or not—are often nonplussed when they encounter radical reconstructions of Jesus and earliest Christianity. Others, of course, applaud them, finding that such radical reconstructions get them off the hook with the traditional Jesus and the Church. Gone is the Jesus who saves us, replaced by a Jesus who either affirms us, or is ultimately irrelevant, or who encourages whatever vague spirituality is du jour. In either case, they are presented with a reconstruction in which Jesus is alone, cut off, isolated—divorced from Judaism, from the Old Testament, from the Gospels, from the Church. The real Jesus, radical reconstructions insist, is some sort of mystic, or revolutionary, or Cynic, or teacher, or prophet, whose Judaism is incidental and irrelevant at best and who has been hidden—often deliberately—by the later dogma of the Church, even by the biblical Gospels themselves.

By contrast, traditional Christianity (whether Catholic, Protestant, Orthodox, or fundamentalist) sees Jesus in terms of continuity. In broad strokes, he fulfills the Old Testament promises, and the Gospels of the Church (however conceived) faithfully record eyewitness accounts of His Virgin Birth, miracles, prophecy, and teaching, his sacrificial death, his bodily resurrection, as well as his commissioning of the apostles to go and make disciples of all nations.

The dominant paradigm reigning in academic biblical studies today was developed largely by German scholars of a Lutheran confessional persuasion in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. D. F. Strauss suggested the disciples made up almost everything in the Gospels out of Jewish legends, while Rudolf Bultmann claimed not only that the Old Testament could not be considered Scripture for Christians (and thus irrelevant for understanding Jesus) but also that most everything in the Gospels was a post-Easter retrojection back into the life of Jesus and thus that we can know next to nothing about the historical Jesus. Meanwhile scholars such as Heinrich Holtzmann were busy arguing that Mark, and not Matthew, was written first among the Gospels, while Walter Bauer was arguing that orthodoxy didn’t exist until history’s victors in what became the later Church invented it, with Adolf von Harnack contending similarly that later Christian dogma was an imposition upon the Gospels, the earliest Church, and Jesus himself.

The dominant paradigm reigning in academic biblical studies today, being developed originally by Germans prior to the horrors of the Holocaust, is also laden with anti-Catholicism and anti-Semitism of a genteel but not necessarily virulent sort. While some like Bultmann did join the Confessing Church and oppose the Nazis, others like von Harnack were busy finding ways to deny Jewish scholars important professorships. In any event, to enlightened German Lutheran eyes, Judaism and Catholicism were cut from the same cloth. They belonged to the old world of sacrifice and ritual which the Reformation and its child the Enlightenment had buried forever. It would be inconceivable to such scholars that common, normal Judaism could inform our understanding of Jesus or earliest Christianity—this is why Germans excelled at exploring Greco-Roman backgrounds—or that Jesus and the earliest Church could be understood in Catholic terms.

The greatest contemporary popular exponent of the dominant paradigm today is Dr. Bart Ehrman, Professor of Religious Studies at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, a former fundamentalist whose forays into textual criticism made him a liberal Christian for a time but ultimately an unbeliever. A friendly convivial fellow and a serious, sober scholar, neither an anti-Catholic nor anti-Semite, Ehrman has sold millions of books popularizing the paradigm of discontinuity in several books, in which he endeavors to show the Gospels are unreliable and that Jesus was an apocalyptic prophet far different from the Jesus Christ the Church has worshipped as divine son of God.

Pitre Revives Lewis’ Trilemma

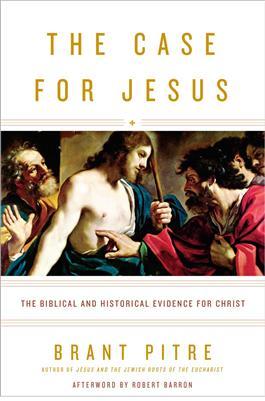

Brant Pitre’s most recent popular offering, The Case for Jesus: The Biblical and Historical Evidence for Christ (Image, the Catholic imprint of Doubleday, 2016), has Ehrman’s work as its gentle target as Pitre presents a spirited defense of the tradition paradigm of continuity among Judaism, the Old Testament, Jesus, and the Gospels. (Full disclosure: I wrote a positive blurb of an advance draft of the book.)

Interestingly, Pitre doesn’t discuss Jesus’ continuity with the Catholic Church, probably be cause he wishes to present an argument congenial to Christians and seekers of all stripes, even as his presentation would be fully at home in Catholic Christianity. Indeed, he begins with an Anglican, the famous C.S. Lewis, who offered the famous “trilemma”: a man who said the sorts of things Jesus did about himself was either a liar, a lunatic (“on the level with a man who claimed to be a poached egg”), or Lord. As most people don’t want to concede Jesus was deceived or deceptive, Lewis’ logic is designed to force readers to accept the third, fateful, option: Jesus was, and is, Lord.

Lewis, a man of letters who expressed explicit disdain for Bultmann and German scholarship, accepted the Gospels’ testimony about Jesus self-presentation as true. At this point the radical paradigm of discontinuity raises its head in protest, however, claiming as Ehrman does that there’s a fourth option that Lewis dismissed: the Gospels do not in fact represent the truth about Jesus, that the Gospels are largely legendary. All, then, hinges on the Gospels’ reliability. If they present Jesus faithfully, then Lewis’ trilemma works. If not, it doesn’t. And so Pitre offers a tour-de-force showing that the Gospels do indeed do so.

The book falls into two parts.

Carl E. Olson's Blog

- Carl E. Olson's profile

- 20 followers