Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 626

July 15, 2011

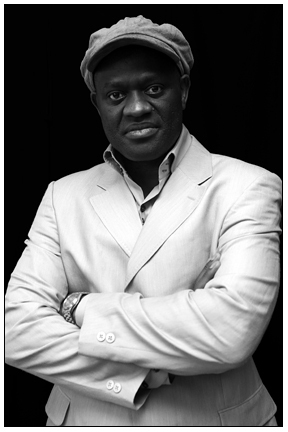

"Mabancool"

In France, Alain Mabanckou is known as "the African Samuel Beckett." Mabanckou left Congo-Brazzaville in 1989 to study law in France, "but quit as a corporate lawyer within a decade," according to The Economist. His first novel, "Bleu Blanc Rouge" (1998), "ironically saluted the French tricolor in its title"; following novels "moved between the dashed dreams of migrants in Paris and the ills of post-independence Africa", his writing permeated with the absurdities of continually translating one's body and intellect within empires that question one's right to be there, here, anywhere.

Recently, France's culture minister, Frédéric Mitterrand, gushed over him, calling him "Mabancool" and a "shining ambassador for the French language" as he presented Mabanckou with a Légion d'Honneur in March this year. Hilariously, Mabanckou's subversions of the French language, suffused with Congolese immigrant city slang and bar-fly speak, was modeled on the manner in which Anglophone writers played in the fields of the British overlords' language. Apparently, the writer's subtle mockery was lost on those minding the rules of the Académie Française, too busy praying that ex-colonials writers will forget exclusions, slights, and outright racist policies, and help win back France's metropolitan glory.

Few English speakers have heard of Mabanckou's work, but only three of his books have been translated to English. But now that he is a tenured professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, more Mabancool may be on its way to us.

Read the review here, in The Economist: Prince of the absurd

Hip Hop and the "Arab Spring"

From "Hip Hop & Diaspora: Connecting the Arab Spring" by Lara Dotson-Renta over at the Arab Media & Society online journal:

The diasporic connections visible in the hip-hop of the Arab Spring, and the many possibilities for future dialogues that these engender are, however, most visible in collaborations such as "January 25," a song spearheaded by Syrian-American Omar Offendum (Omar Chakaki) and Iraqi-Canadian The Narcicyst, produced by Palestinian-American Sami Matar with appearances by Palestinian-Canadian singer Ayah, and African-American converts MC Freeway and Amir Sulaiman. A single song centered around the January 25 protests in Egypt, which heralded the overthrow of long-term President Hosni Mubarak, rallied together artists from all over the world. While united for the same cause, many had not ever resided in the MENA region and several did not speak Arabic natively. Yet, the common factor of breaking silence and having shared a sense of being 'on the outside looking in' sociopolitically created a song that has generated over 200,000 hits on YouTube. Omar Offendum understands the nuanced importance of the premise of unity, as he raps: "From Tunis to Khan Younis/the new moon shines bright/as The Man's spoon was/as masses demand rights/and dispel rumors of disunity/communally removing the tumors…"Having established a common link, the lyrics then take a decidedly American political twist while remaining entirely relatable to the Egyptian political situation with the lyrics of Amir Sulaiman, who rhymes: "wont be just niggas/wont be just spiks/a-rabs, pakis rednecks and hicks/the leaders ain't helping them feeding their kids/the leaders helping pigs eating their kids/got me back on my Elijah eating to live/run up in the white house like I got a key to the crib…"

You may read the article in its entirety here.

h/t zunguzungu

July 14, 2011

Hillywood

The program of selected films and documentaries for this year's Rwanda Film Festival going down this weekend and next week at the KWETU Film Institute in Kigali is an eclectic bunch (amongst many others, there is Na Wewe, Le Mec Idéal and Afrique en Marche). One of the documentaries I hope to see sometime is 'Surfing Soweto' (trailer above). Anyone around to give us feed-back?

Music Break / DJ Hamma and Jitsvinger

We liked the previous recent work by DJ Hamma and Jitsvinger. No surprise then the result of the two of them collaborating is dope. The track is lifted from the album we blogged about last year, but the video's new. DJ Hamma says: "We shot it in August 2010. I was initially very disappointed with the shoot and the footage. Too much drama… The footage wasn't enough, not what I asked for and didn't follow the initial storyline we had in mind. I wanted to redo the shoot but got caught up in my life and travels as a dj and producer. I just about gave up on it but due to the mounting requests from people for this particular song I decided to have another look at the footage. The idea was to see if I could slap something remotely decent together to become the 'unofficial' video representation of this track. "Niks om te se nie" translates as "Nothing to say". Jitsvinger expresses his views regarding modern day mc'ing. He feels that mainstream hiphop lacks lyrical substance and doesn't really relate to the mind and thinking of the general listener or followers of hiphop music. In the end it's all politics. It's like he sees it as the common fast food franchise… no matter where you buy your meal it will taste the same… Mc's became these carbon copies of what they see on tv. We believe in 'doing us'… this song expresses that to the fullest and with no apologies nor shame."

Blitz on NPR

Driving around upstate NY last week, we tuned into NPR, to hear Samuel Bazawule talking about the one thing he wanted as a young kid growing up in Ghana: tapes of Tribe Called Quest, de la Soul, and the Jungle Brothers. And more than anything else, he loved Public Enemy.

Samuel Bazawule? Yup, that's Blitz the Ambassador. For "most African families," he says, "it's all about education. It's really about having the standard jobs: the doctor, the lawyer." So of course, he went to Kent State, and graduated with a business degree. But he found himself drawn back to rap, to rhyming.

We sat in the car, eating blueberries intended for a tart, listening to that story. I was trying to convey to my partner, who grew up in Bombay, why this story resonates for so many '80s kids from Africa: rap told us that across the water, there were these Someones, saying it smarter, harder, and sometimes cruder. And we wanted to say it like that, and be like that. Not our tame, boarding-schooled, uniformed, behaved selves, headed for degrees in medicine, law, and engineering. We wanted to engage as they did, and recognise our part in 'it' (whatever that 'it' was). So when my pal from down the street in Kitwe, Zambia blasted some old school rap on his beat box at the university we both ended up in Iowa, a Southside Chicago guy showed up at the dorm room, wondering why we were behind times, but…still, cool enough. We weren't 'African' in Zambia, but in Iowa, we were becoming just that – because we loved the same music, and wanted to engage with the message - at whatever juvenile level we could, at the time.

Here's Blitz on NPR, speaking about how 'complex rhymes' helped him memorise whatever he had to for classes in Kent State, and how he now teaches rhymes to kids as a substitute teacher whenever he's not recording.

Photo Credit: Tobias Freytag

Drones in Somalia

With new reports of drone strikes by the American military in Somalia–the aim is to take out after members of Al Shabab– and a CIA base (and prison) in Mogadishu, I asked Alex Thurston, also the blogger know as Sahel blog, to unpack what's going on. He sent this 1000 word post. It's very informative–Sean Jacobs.

By Alex Thurston, Guest Blogger

American military involvement in Somalia is increasing. Jeremy Scahill of The Nation reports that the US recently conducted as many as four drone strikes on targets linked to al Shabab, the rebel movement that controls much of southern Somalia. Scahill has, moreover, revealed the existence of a CIA base in the capital Mogadishu, where American operatives train Somali intelligence agents and reportedly participate in interrogations of suspects accused of being terrorists. American officials seem to believe that such involvement is necessary in order to weaken and contain Somalia-based terrorists. Confidence that warfare is changing – in other words, costing the US fewer casualties – appears to encourage the gamble that a light American presence will have minimal political repercussions. Yet Washington, which has misread the political situation in Somalia before, may once again be pursuing short-term military gains at the risk of long-term blowback, both in Somalia and at home.

Direct and indirect American participation in Somalia's civil war is not new. Following the collapse of Siad Barre's regime in 1991, US troops deployed as part of the United Nations Operation in Somalia. When a mission to capture a warlord went wrong in the "Black Hawk Down" incident of 1993, nineteen American soldiers died, and US forces exited Somalia. In late 2006, concerned about the rise of the Islamic Courts Union (ICU), a movement reputed to have terrorist ties, Washington backed an Ethiopian occupation that lasted until early 2009. The fall and fragmentation of the ICU, combined with the brutality of the Ethiopian occupation, facilitated the rise of al Shabab, the ICU's military wing. Washington has designated al Shabab a terrorist organization (the group has proclaimed ties to al Qaeda), and seeks to deny the movement a base for international terrorist operations. Ethiopia's withdrawal initiated the latest phase in the civil war, but did not end US involvement. In 2009, a US helicopter raid killed Saleh Ali Saleh Nabhan, a Kenyan-born al Qaeda operative who was working with al Shabab. In addition to military involvement directly or by proxy, the US has over the years provided support to various would-be governments, including the Transitional Federal Government (TFG), which is currently battling al Shabab for control of southern Somalia.

The drone strikes and the CIA presence form part of this history of American intervention. As before, the current strikes could give a political boost to al Shabab. Former Ambassador David Shinn recently told Congress that some previous US military strikes "have resulted in collateral damage and others, according to accounts from many Somalis, have generated sympathy and even served as a recruitment tool for al-Shabaab." Shinn recommends limiting strikes to high-value targets, and cautions that the risks of expanding strikes outweigh the benefits of killing significant, but easily replaced, commanders.

The fight between the TFG and al Shabab has also increasingly affected East Africa and distorted American relations with the whole region. In addition to precipitating the Ethiopian occupation, Somalia's crisis has spilled into Kenya as refugees flood in and fears grow that Kenyan-Somali youth are joining al Shabab. Uganda and Burundi are the major suppliers of troops to the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM), the force that has been instrumental in the TFG's meager gains against al Shabab in Mogadishu. Uganda became a target of al Shabab when suicide bombers struck the capital Kampala in July 2010.

The roles of Ethiopia, Kenya, and Uganda in fighting al Shabab have confronted the US, which considers all three countries allies, with ugly trade-offs. The imperative of fighting terror coexists uneasily with stated US agendas of democratic reform, a concern in dealing with Ethiopia and Uganda, whose democratic credentials are questionable, as well as with Kenya, whose 2007-2008 electoral violence may foreshadow a bloody sequel in 2012. When the US attempts to influence the course of events in Somalia militarily, it not only participates in Somali politics, it compromises on core values throughout the region.

American political involvement in Somalia also risks causing political blowback within the Somali-American community. Ties are tight between Somalia and its diaspora. What happens there matters abroad. Arrests of Somalis in the US on charges of plotting or aiding terrorist operations suggest that a significant minority of the Somali-American community sympathizes with al Shabab. Several American citizens have died fighting for al Shabab already. The Ethiopian invasion of Somalia increased anger at Washington within the diaspora, and more American involvement in Somalia could stoke that anger. In the worst case scenario, an angry Somali-American might conduct a successful terrorist operation within the US.

The two trends signaling deepening military involvement in Somalia – drone strikes and the CIA presence – are the same trends taking place in American military operations around the world, and they are the same trends that nurture the belief that the human and political costs of warfare are decreasing for the US.

Costs are indeed decreasing to the extent that there is less risk now of American casualties in Somalia than there would be if troops deployed there. Moreover, the militarization of the CIA has, in Libya and Pakistan as in Somalia, allowed Washington to say it has no "boots on the ground," and thereby reduce domestic outcry concerning risks to US personnel.

But politics don't end at the water's edge. As happened in Pakistan with the case of Raymond Davis, a CIA operative who came to worldwide attention when he shot two Pakistanis and was subsequently imprisoned, a disaster involving even one American official abroad can quickly become a political problem for Washington. And if Americans pay less attention to drone strikes overseas than they do to deployments, that is not the case for communities where strikes fall. If America's indirect involvement was known and resented when Ethiopia invaded Somalia, its direct involvement through drone strikes will likely be known and resented as well. The Ethiopian invasion was the crucible in which today's al Shabab was, despite American intentions of neutralizing Somali Islamism, formed. The political outcome of present American military involvement in Somalia could be equally unpleasant.

* Merci to Jacob Mundy for the connect.

The New South Africa

UPDATED: The blogs have rightly been outraged at a white couple, "Dave and Chantal," who decided on a "colonial" (and Apartheid) theme at their wedding in South Africa complete with an all-black waiter staff in red fezes. Like it was a scene out of the film "Out of Africa." (Turns out the happy couple asked for a recreation of the film. Serious.) The wedding was held in Mpumalanga province on the border with Mozambique. The wedding organizers got the props–which included "antique travel chests, clocks, globes and binoculars and an awesome Zebra skin"–from a "prop house" in the capital Pretoria. This kind of thing which is apparently the in-thing (i.e. sold as "tradition" and "nostalgia"), would have passed unnoticed, but for the internets. The couple or their photographer felt pleased enough to post the pictures on a photography site. Then it was spotted by the American blog Jezebel (part of the Gawker empire). Once it became viral (and the couple their photographer and wedding planner were ridiculed) some of the photos (i.e. those with blacks in subservient positions or white people hamming it up in pith helmets) have been taken down. Here's a link to the "cleaned-up" cache-page since the page has been deleted. Luckily for us screen shots of the pictures exist. Of course, not surprisingly, some white South Africans are defending the couple. (Although one commenter spoke the truth: "Most white folks' weddings in [South Africa] are colonial not by design, but by default.")

At least they can't blame Julius Malema for this. Although a few brought him up.

Above and below are some of the offensive photos. Then following the photos, at the bottom end of this post, see commentary from Neelika.

More from the big blogs, here and here.

Neelika Jayarwadane adds: First, the pith helmets, the rolling amber whiskey, the monogrammed blue sweaters: it's like a Tommy Hilfiger/ Ralph Lauren advert for Fall-wear, in the conservative chic for which these brands are known. But allow me a little snark here: who wears a blue sweater, no matter how finely monogrammed, to a proper wedding? I see it's all very shack-chic-themed, with corrugated walls and chandeliers, but still, lovey.

Second, Hilfiger and Lauren get their imagery from the fantasia of Africa created by Hemingway and Hollywood: Baronness von Blixen, channelled by Meryl Streep in Out of Africa, to be more precise. There, one can marry that lovely hodgepodge of elements evoking a magical time when we just didn't know to be embarrassed by our colonial selves: hunting, whiskey, fine food served on Limoges china, and most importantly, the silent, disappeared bodies of the 'service' – seen here in the full glory of their outlandish and out-of-place carmine fezes (a nod to East African Muslim traditions?). When modern South Africans want to revert to the safety of the good ole days, when whites were whites and servants were marked by uniforms and ridiculous headgear, apparently they turn to '80s Hollywood for their references.

'The last photo before leaving'

Kwa Heri Mandima (Goodbye Mandima) is a short film by the French-Dutch director Robert-Jan Lacombe doing multiple film festival rounds over the last year. Born in 1986 in Mandima, Robert-Jan — and his family — left Mandima, the village in northeast Congo (then still Zaire) ten years later. A short interview with the director (in French) can be found here. Thoughts?

What about the maid?

By Dan Moshenberg

Monday was World Population Day. At some point in October, the world population will hit seven billion. How is one to focus on seven billion people? Some say, focus on "trafficking". In particular, focus on African women trafficked to other countries.

For example, Makeda. Makeda is Ethiopian. She works as a domestic worker "somewhere in the Middle East." She has a hard life, a life largely defined by workplace abuse and exploitation, and by abuse and exploitation by "traffickers."

The issue of "trafficking", of coerced and abusive transport of workers, is critical and contentious. At the same time the trafficking framework too often displaces all other narratives.

So, let's return to Makeda, but with a difference.

Makeda is an Ethiopian woman. She works as a domestic worker in another country. As a woman, as a worker, she has a hard life. How have African and African – derived domestic workers responded to such conditions?

Across the continent, domestic workers are on the move. For example, since 2000, the South African Domestic Service and Allied Workers Union, SADSAWU, has been organizing, securing new legislation, new conditions, new consciousness. SADSAWU builds on decades, and centuries, of South African household workers organizing.

Domestic workers across the continent have organized since the invention of paid domestic labor. And African and African-derived domestic workers have been organizing in the United States.

This year, New York passed the Domestic Workers Bill of Rights. Who made that happen? Domestic Workers United, "an organization of Caribbean, Latina and African nannies, housekeepers, and elderly caregivers". Women like "Esmerelda", nanny, elder care provider, housekeeper, originally from Zambia.

Out of Domestic Workers United came the National Domestic Workers Alliance, organizing across the country. Yesterday, they brought 800 organizers and supporters to Washington to launch the national Caring Across Generations campaign.

Among the 800 were Dora Tweneboah and Margie Obeng, two young women just out of high school. Both Dora and Margie are from Ghana. Dora has been in the United States for four years, Margie was two years old when her family arrived. They are both youth organizers in the Tenants and Workers United of Northern Virginia, and they have something to say about "the plight" of domestic workers.

Dora commented: "Coming from a country where there is suffering and poverty, I noticed the hardships of people, especially young women and children, who are forced into labor and commercial sexual exploitation. In Ghana, trafficking is local, and it mostly involves children and young women. Every day, children and young women are forced to labor in agriculture, street hawking, fishing industries; to work as porters; or to beg, most often for religious instructors. Girls are mostly trafficked within the country for domestic servitude and sexual exploitation. They work 24 hours a day without pay and often without food. As a youth organizer, I think a discussion about women and trafficking is needed. Women here work for other people every day and don't get enough money to support themselves and their family. They're told to stay silent, not to reveal the secret of being forced to work. Otherwise, it's back to the street or back to their countries. Trafficking is an issue for domestic workers and care givers."

Margie replied: "Coming from a culture with strong teachings of respect for adults and people in general, I think care hits home for me. Several of my aunts and family friends work in areas where care is the entire basis of their jobs: RN's, LPN's, CNA's, live-in nurses, nannies, day-care owners. These people care so much about the work they do, and take such good care of their clients, but too often their work is unrecognized. That needs to change. Around here, so many African women do care work. They are loving, caring, hard-working women trying to earn an honest living. Like so many other immigrants in this country, these women do the work that many don't respect or recognize … but need. If Ghanaian and immigrant workers generally become aware of such campaigns, they could spread to the home countries because care jobs are international, not just in the US. The rights of the worker should be recognized wherever they are."

Want to focus on African women domestic workers? Fine. Focus on the struggle for dignity and the challenge to care. Leave "plight" at the door, please.

* Image from Ian van Coller's "Interior Relations," a series of portraits of domestic workers in South Africa.

July 13, 2011

Music Break / Baaba Maal and Duggy Tee

My Brooklyn neighborhood is a center for Pulaar speakers in the United States. The community has its own association, a significant proportion of the local masjids' membership, and plenty of great restaurants that provide food from countries like Sierra Leone, Guinea, Senegal, and Mali. Baaba Maal and Duggy Tee get together on a track that would make the neighborhood proud.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers