Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 624

July 22, 2011

Music Break / The Plastics

The Cape Town band called The Plastics. They worked with the guy who produced The Strokes, Gordon Raphael. They just emailed him and told him they loved his work, as a long shot. He had seen the BLK JKS perform in New York City and liked them so he thought he'd give them a try because they were South African. If the song comes across as too soft for some people, it is a nice video. And there's a 2BOP sweater in there too.–Dylan Valley.

Weekend Special, July 23

* Philip Gourevitch, of The New Yorker, probably still healing from the mauling he got over his admiration for Paul Kagame (and probably regretting losing his cool), decides it's may be better to write about Rwanda's national cycling team for the magazine. (Hint: It's Tour de France month so let's publish a piece about Africans and cycling.) Read it here. And here listen to Gourevitch talking about it.

* Rapper 50 Cent gets ambitious.

* You know of the Zambian reality show for 'former prostitutes', aimed at teaching them baking and general cookery, so that they can find a husband? Winner has wedding paid for. Seriously.

* People get book deals for this kind of nonsense: First World Problems. Remember Stuff White People Like?

* "Four elderly Kenyans who say they were tortured by the British during the Mau Mau uprising have won the right to sue the Government. The decision is expected to encourage people around world to seek compensation claims against Britain for atrocities carried out under colonial rule." And spare me the talk about reconciliation.

* Black people apparently don't go to Museums, tip, see a therapist or agree on what black people don't do. Apparently.

* The New York Times tries its hand at reporting cricket. Good publicity for new film, "Fire in Babylon," about the victorious West Indies cricket team that dominated test and one day cricket between the mid to late 1970s and the mid-1990s. The obligatory Joseph O'Neill quotes. But then the illustrations. That's not Viv Richards in the picture. I've been having a back and forth with fellow South Africans Jonathan Faull and Tony Karon about this and we agree that's someone else. I think it is Gordon Greenidge but they disagree. Cricket people?

* On film itself, this is what a Bajan told me: "… On one hand it was great to see all that classic footage of West Indies cricket domination and I'm so happy that someone captured that remarkable time…I loved the segment on West Indies tour to Australia in 1976 and the [Kerry[ Packer years and the new team that emerged. That stuff was gripping. But most of it felt surface and obvious and I'm not sure if that's because I know so much of the material already or because it was surface and obvious. There wasn't really a problem to explore and it's convenient how the history of the team ends before the abysmal plummet that any current fan of West Indies cricket is grappling with. There's definitely a Part 2 that begs the question What the Hell Happened Next ("Who Killed King Cricket?") which is what really consumes West Indians, the few who still care. I mean we couldn't even get anyone to go see India play in Barbados this current test series."

* If you don't already, sign up for alerts from the Committee to Protect Journalists' Africa researcher Mohamed Keita. Here

* "Who's created Mofongo?":

* The "development-induced" displacement of the Ogiek people in Kenya (from Survivor International):

* The documentary film, "War Don Don," about the trial before the International Criminal Court of an infamous Sierra Leonean rebel soldier has been nominated for two Emmys: For "Outstanding Continuous Coverage of a New Story–Long Form" and for "Outstanding Editing."

Remember the trailer:

H/T: Our Stories, Neelika Jayawardane, Tony Karon, Jonathan Faull, and many others.

Colonialism

A satirical film made by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation in 1986.

Worth seeing again.

July 21, 2011

Murdoch and starving Somali children

What's in the news these days?

a) New reports of famine in parts of Somalia, Ethiopia, and northern Kenya, alongside the difficulties of getting food and medical aid to areas in which famine is partially caused by what's often referred to as the 'political conditions'.

b) The so-called phone hacking scandal in which News Corp.'s Rupert Murdoch and his clan are embroiled – but which is not really about News Of the World reporters hacking Sienna Miller's phone to get the juicy bits about her sex life, but more about Murdoch's successful bid to be in the business of power and political influence (David Cameron included), rather than in the business of the fourth estate.

So how to deflect a scandal that may lead to severe restrictions of one's sphere of influence? Use your own PR company, and have one's editorial cartoonist link a) with b). The Times of London, owned by Rupert Murdoch's News Corp, had resident cartoonist Peter Brookes draw up "Priorities," a cartoon depicting a group of starving figures in a desert environment; one figure clutches the tell tale empty begging bowl, and states, "I've had a bellyful of phone hacking." (Peter Brookes, btw, has a thing for drawing starving Africans.)

Ah, Murdoch. Don't project your anxieties/self-loathing onto the bodies of starving Africans. That's you, there, who's had the bellyful. It's almost like Brookes modeled the figures in his cartoon on Murdoch – right down to the big ears.

Music Break / Nomadic Massive

New video for the Montreal-based all-star (and all-country) band Nomadic Massive. Not sure why they haven't got a bigger following.

Flash Mob

No it's not a protest. It's PR for the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University in Port Elizabeth in South Africa's Eastern Cape. To get you to come and study there. The singers are from the University Choir and it's in that classic new South African public space, a shopping mall. Someone's already conjuring up metaphors about rainbows and how this what Mandela was all about. Calm down people: it's only PR.

H/T: Nerina Penzhorn.

Malawi Spring

By Dan Moshenberg

Did you hear about Malawi Spring? It started Wednesday, July 20. Thousands of people filled the streets of the capital Lilongwe, the commercial capital Blantyre, the northern city of Mzuzu, and elsewhere. Police are accused of having killed protesters, protesters are accused of having looted. According to the Western press, the streets are filled with riots, "anti-government" protesters, and eruptions of violence. The demonstrators are against the government, the police are against the protestors. But what are the protests for, and who are the protesters?

None of the reports mention women. In and of itself, this omission would be bad enough, but given that this particular `spring', just like those in Egypt and Tunisia, concerns rising food and fuel costs, the absence is glaring. In Malawi, as elsewhere, women not only purchase and prepare food, they farm it.

So, where are the women of Malawi?

They're farming. Women farmers, like Esnai Ngwira, are investing in new, environmentally appropriate and sustainable farming techniques. Ngwira, a 57-year-old farmer in Ekwendeni, northern Malawi, has been working with a program that builds social ecology in sustainable ways. Rather than using fertilizer, for example, Ngwira uses crop residue. She gets a better maize harvest, helps the soil, helps the earth. Esnai Ngwira is "a star innovator."

Women are engaged in new projects in agroforestry, which not only provides their households with firewood and income, but opens their daily schedules for other endeavors.

Malawian women are at the forefront of struggles for land access and ownership. In Malawi something like 80 percent of the land is communally owned. And so women are organizing into groups that, as a group, control and benefit from land the women farmers either lease or own. Women, like Maggie Kathewera-Banda, of the Women's Legal Resource Centre, are researching, organizing, engaging and empowering rural women. Researchers and farmers understand that access to land and to household bargaining means access to power.

Village women like Ethel James face polluted and fetid water where once it was clean. Infrastructures have collapsed. One borehole serves all of Kwilasha village in Machinga District, in southern Malawi. Women spend, or waste, whole mornings in pursuit of a single bucket of water. So, the women organize. They develop skills to fix the existent pipes and to lay new ones.

Women, like Tiwonge Gondwe, are health activists, feminists, movement builders. They take HIV and AIDS and turn the stigma on its head. They organize communities … across the country.

The stories could continue. Life in Malawi is hard. It's a poor country, fuel and food prices are on the rise, the UK recently cut aid because of perceived mismanagement, the State is arrogating more and more power to itself. LGBTIQ people and communities are under attack. None of this should be minimized.

At the same time, a mass protest, perhaps the beginning of a next phase of engagement, perhaps not, does not occur in a vacuum. In Malawi, as in Egypt, as in Tunisia, as around the world, spring means harvest. Harvest, in Malawi, as across sub-Saharan Africa, means women farmers. Where are the women? Not in the news reports of the Malawi spring.

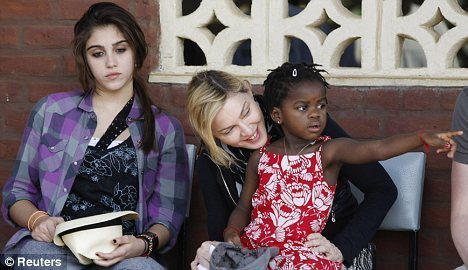

The stories and images of Indians in South Africa

The National Gallery in Cape Town, South Africa is currently exhibiting photographs published in DRUM magazine, circa 1950. Above, Director Riason Naidoo speaks to me about growing up in Chatsworth, an area delegated for those classified as "Indian", what got him interested in early photography of colonial subjects, and why he decided to embark on a project looking up and collecting the stories and images of Indians in South Africa.

The exhibit highlights the rich history of the Indian experience as featured in the pages of Drum Magazine:

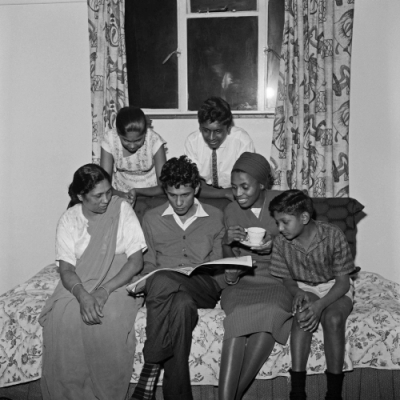

Indian gangsters (Sheriff Khan, who was known as 'South Africa's Al Capone'), golfer Papwa Sewgolum, activists like Yusuf Dadoo and Monty Naicker, Indian footballers, glamour models in pretty bikinis, daredevil motorcycle riders (fantastic shots of the woman stunt rider Amaranee Naidoo on her Harley Davidson, circling the heights or a circular ramp), and ballroom dance champions. There are images of "Jazz King" Pumpy Naidoo, a series documenting the feud between the 'Salots' and the 'Crimson League' gangs, and one priceless photograph of Sonny Pillay, who was dating Miriam Makeba at the time, surrounded by adoring family members: they crowd around a sofa, looking through what appears to be a photo album, while Miriam sips tea.

Others are of images of child labour on the sugar farms in Natal, and dire depictions of the living conditions in the ghettoes.

[image error]

Naidoo first collected these photographs the book, The Indian in Drum Magazine in the 1950′s (Bell-Roberts Publishing, 2009). They were selected from a few hundred thousand uncatalogued negatives, and challenge conventional and 'official' portrayals of the South African Indian community, revealing aspects of 'Indian' history that have rarely been seen by those outside of it.

Many of the photographs featured in the book are on now at the National Gallery, together with another exhibition profiling the work of Ranjith Kally (b. 1925, Isipingo) who began his career as a photographer while working at a shoe factory in Durban:

…[h]e came upon a Kodak Postcard camera at a jumble sale in 1946, which he bought for six pence. 'I was consumed by my newly found interest in photography and spent almost all my free time pursuing the art form', he remembers.

Here's an example of Kally's work; Miss Durban 1960 Rita Lazarus.

[image error]

The exhibition has been on show since 11 May this year and will go until 11 September.

Sesotho Cipher

Before moving down from Maseru to Cape Town in 2008 and exploring the Cape's hip hop scene, Core Wreckah was already heavily involved in Lesotho's capital hip hop scene. When we saw him plugging his new song 'Reverb' here and there on the web, we thought it a good moment to throw him 5 questions about what both scenes have in common, and what sets them apart. But more about that plugging after the song:

How has Cape Town been treating you over the last three years? Do you feel at home? Has the city and its people been welcoming? Inspiring, as an artist?

It's been good I suppose, similar to home in the sense that everything that one needs in order to survive is within reach. I found the hip hop community to be quite accommodating, so that was an added bonus – it enabled me to build relationships from very early on.

The disparity in living standards, and inter-racial separation (don't really want to use the word 'racism' since I've given up trying to understand what that even means in a South African context) has been a bit of a shock. Growing up in Lesotho, one never witnessed the levels of segregation which exist between races here. (I wrote a song regarding my feelings about the issue: 'Looking at me.') I went to see comedian John Vlismas recently; he made the observation regarding the comparison between South Africa and a rainbow (i.e. the rainbow nation), and commented on how fitting it is since no matter how hard one tries, they can never mix colors of a rainbow. I thought that was a very apt way of putting it.

As an artist, it is only in the past year that I have taken an active role in terms of getting myself onto shows, and generally trying to get as many people as possible to hear and give criticism of my music. I had been lax to do this for various reasons before, but one of the main factors was that I needed to get a feel of the scene in its entirety; it is easy to get stuck with one group of people, which then leads to stagnation. From very early on, I have been interested in becoming a well-rounded artist, and have found that my involvement (either directly or indirectly) in the various scenes in and around Cape Town has had — and continues to have — a positive impact on my artistic output.

'The scene in its entirety,' that sounds daunting. You're referring to the hip hop scene? Locally, nationally? How would you describe the scene? You find it 'accommodating'. How so?

The 'entire scene' refers to my need to inspect from the side-lines what was happening in Cape Town hip hop, which events to go to, which rappers were making an impact, which breakers and writers were noteworthy, etc. This was important since I could then have an idea of who did what, who one needs to go to to get something done… and so forth.

I found it accommodating in that there was no 'gatekeeper' mentality; people were willing to let me become part of what they were doing. For instance, Driemanskap and Ill Skillz allowed me to sit in on a session one time; I hung out with Rattex a lot, and he bumped for me songs which he was recording during his 'Bread and Butter' album sessions; most of those songs made it onto the final product.

Part of it could have been because of me asking nicely, and part of it could have been due to the fact that I wasn't just another rapper trying to be down with them, or trying to get onto a show, or doing whatever it is that makes people become guarded. So it was 'accommodating' in the sense that I got to form good relationships without a prolonged amount of effort.

Are you still in touch with the hip hop scene in Lesotho's Maseru? Is there a scene beyond Maseru? And is it in any way comparable to what's going down in Cape Town? Is there a line (of communication, of interest, of collaboration) between both scenes?

I am still very much in touch with the scene in Maseru, that's home, that's what I represent in songs and every time I get on stage. I've written a column for the past four years which focused on the Lesotho hip hop scene, and started a blog (in 2008) which had as its main focus the promotion of Lesotho hip hop.

I am not very much aware of the scenes beyond Maseru. I mean, I know of a few people from elsewhere (e.g. Kommanda Obbs and Suuth from Maputsoe, and Mohalakane, a group from a district called Quthing). Apart from that, it's very hard to get music from elsewhere in the country; perhaps people are not so much interested in promoting their music beyond their immediate environment.

The scene where I come from is very much street-level though — a lot of ciphers, lots of 'bedroom' recordings, a lot of hand-to-hand CD sales. There are no regular performance slots, and Maseru's nightlife as a whole is pretty non-existent — but that's what I hear from people, and cannot comment much since I rarely go out at night unless it's to support a poetry event or an independent movie screening.

On the other hand, Cape Town has a small but vibrant scene; there are regular events (Kool Out, Party People, etc), and park jams which ensure that hip hop is well-represented, and that rappers have a platform on which they can showcase their creations. So Cape Town is much more 'advanced' in comparison to where I am from…which is all fair and well since the standards of living (economic and otherwise) are different in the two places.

In terms of collaborations, I personally do not know many Cape Town-Maseru collaborations; I know of mc's who are from Maseru originally — now making a living in South Africa — who have done collaborations. For instance, Konfab has done some work with Dplanet (CEO of independent imprint Pioneer Unit), and Arsenic (of Manic Mettaloids/Writers Block). I think Hymphatic Thabs has also worked with Arsenic on some songs. On my part, I am constantly looking for people to collaborate with, but it is not always easy. I suppose people are too busy working on their own projects to bother.

How has the use of new channels like twitter, facebook, youtube, bandcamp and soundcloud influenced your way of trying to get noticed? Are these media efficient tools in South Africa to get your music up and out? I'm asking this because it's maybe a bit too easy to rave about them while so many South African (or Sesotho) hip hop heads simply have no access to these media (not everybody has the money to regularly recharge their smart-phones or spend hours on-line in internet cafes).

Twitter is cool, I like it for the ease of use, and the randomness with which I found it (I clicked on a link on someone else's blog about three years back, got taken to the site, and have not really looked back since). I'm not quite the fan of facebook, but it has its uses I suppose. I worked on a documentary in 2007 which was concerned with exploring Lesotho's cipha scene, and youtube has been very central in letting me put that on so that anyone from elsewhere in the world can check out what I've done; I've also uploaded mine and my band's performance footage on there.

I love soundcloud for how it enables me to discover other musicians's work. For instance, I'd been a fan of Namibian BecomingPhill for a long time, and totally bugged out when I found him on soundcloud. The dude is pure genius, and I think someone needs to get him a premium account so that he stops having to delete some stuff in order to upload new songs. Same goes for Hiperdelic, a producer from Cape Town.

While I have used bandcamp and got some benefit from it, there are still so many more avenues for me to explore within its framework (e.g. the physical goods store). I find it very useful, especially when it comes to collecting people's e-mail addresses; as the argument goes, e-mails have sort of become the new 'currency', though I'm not sure how much I agree with the statement. Having one's e-mail address and sending them updates every now and then does not necessarily mean that they'll read what the mail is saying, but it does definitely increase the likelihood.

Bandcamp has been efficient in getting my music out, as has soundcloud. But what I have discovered time and time again is that people seem to be…I don't like using the word ignorant, but rather lax to check out links to music from those they do not know. I say this because I am part and parcel of that 'unknown' bunch, so even managing to get a single play on my soundcloud is a big achievement for me. But write-up on blogs such as Welfare State of Mind, okayafrica, 25tolyf, and others have certainly helped to direct a bit of traffic onto the portals on which I am present.

As for the point you raised about it being easy to rave since one has access to the internet…well, look, I have been able to achieve a certain amount of presence on the web even before I had a fairly stable internet connection. I have a very good friend, Lyrical Bacteria, from Lesotho who — though not always connected to the net — has managed to do amazing things for both himself and Lesotho's poetry scene. His work ethic is impeccable to begin with, and the small chances he gets to go to an Internet cafe he utilizes those wisely. Also, that connectivity argument is tramped by the fact that there is mobile connectivity now in Lesotho, we have 3G and HDSPA technology — though still a heck of a lot expensive — making the rounds. An investment of at least 50 maloti (that's our currency, equal to 50 rands) every once in a while will ensure that one has enough data to upload their work on-line, synch their accounts so as to make a single update and feed it to all social media, etc. I know that there are people who have made do with the very limited resources we have. Big shout-out to producer San the Instru-monumentalist who has also managed to release a compilation (Classic Dirt which has on it among others, myself, John Robinson, Moka Only, The Holstar, etc) using those very same 'limited' resources.

It's very easy to suppose that having access to all these social media tools automatically grants one some sort of magical key into the world. I have found that basic rules still apply; a 'please' and 'thank you' will go a long way, etiquette is not negated by on-line presence; in fact, I'll argue that it is even more essential since most of the time one is communicating with people one has never met, and the person being communicated to has no onus to even bother replying to whatever request it is directed at them.

You recently wrote a beautiful ode to Sankomota, a band, you say, which "has served as my sanctuary whenever music seems to loose track" but you also hint at the fact that "we betrayed the memory of a legend." In what way do young Sesotho artists keep the memory of their musical forebears alive, if at all?

From my side, I have a vested interest in Famo (traditional Sesotho music performed with the accordion), and have been researching its origins as well as making a collection of music from the musicians who impress me the most.

One of these musicians, Famole, died around 2004; he was quite instrumental in introducing a sort of paradigm shift in terms of how the music gets performed; his lyrics were striking in that they were a concoction of post-apocalyptic revelations (with a strong Christian undertone, as well as semi-battle rhyme-like (he has the dopest braggadocio songs). He was a man very aware of his own mortality, yet also equally aware that life is to be lived as well as enjoyed.

Famo musicians — as far as I know — do not write their songs; so to me, we as the younger generation have this library of people who have hardly gone to school, yet are able to weave together narratives potent enough to stand neck-a-neck with those of the best scholars the world has to offer. Of course the language is different, but the dynamics are the same: the setting, the build-up, climax… all these elements are contained within these songs.

For me, the artist Famole best personifies what I would like to achieve with my music: a man capable to engage his audience by using elements from the environment, objects such as names of towns and/or activities that people can easily identify with. So in my music, especially my Sesotho stuff, I sort of channel — though reluctantly, being careful not to loose myself in the process — what to me Famole's music personified, and still personifies. But it's not only him that I look up to… the music of Letsema Mats'ela also strikes a deep chord within me, and I also channel him — especially with regards to my vocal intonations.

I have also recorded a song (still to finish it though) whereby I address the issue of murders within the Famo community. Legends such as Sanko, Lesholu, and most recently Selomo, have succumbed to the violence which seems to be rife in Famo music. The song is a call-to-arms of sorts, but from the perspective of a hip hop head.

In the greater scheme of things, I have not heard a lot of homage being paid to our musical heroes by my fellow artists, but this could also be attributed to the lack of a functional distribution channel for hip hop artists in Lesotho. However, a lot of my friends are very clued up on our traditional as well as contemporary Sesotho sounds; it is perhaps just a matter of time before that awareness translates to them incorporating elements of that into their musical compositions.

Papa Zee and Dunamis (both quite well known in Lesotho) are the only two people I know of who have actually recorded songs with Famo contemporaries. Besides that, I haven't heard much.

So in conclusion, there is an awareness that the legacy of those who came before us has to be preserved by Lesotho's hip-hop community. I have a feeling that the time is near when this awareness shall translate into actualization through music.

July 20, 2011

TMZ's Harvey Levin and the murderous 'natives' in the Congo

I grew up in the Copperbelt Province, near the small mining town where Dag Hammarskjöld's plane crashed in September 1961, as he was en route to negotiate a cease-fire in Katanga Province in the Congo. My father, who stuck a small map of the continent on our bedroom wall, and warned us to memorise the 50+ African states within a month of our arrival in Zambia (I was 7), was full of obscure facts that meant little to us at the time. He chugged us to Ndola in his beloved bottle-green VW beetle, and made a sweep around the tiny airstrip: "This is where the great statesman died, perhaps because of treachery," he said.

So imagine my surprise when TMZ's Harvey Levin (yes, the gossip "news" show) pronounced Hammarskjöld's death to have been at the hands of 'natives' 'in the Congo' who tied Hammarskjöld to a tree, and split his body apart. Even as his staff members Googled 'Hammarskjöld' (and mangled Hammarskjöld's name; Levin called him "Dog Hammerfield') and found that he died in a plane crash, Levin holds on to his story: the natives must have split Hammarskjöld's body, posthumously. He then benign-dictator-style ordered a staff member to get a hold of a "professor" who knows something about the Congo, to confirm his story.

Around 9:30 AM, I went on TMZ's website, and wrote them a note: I grew up not 60km from the crash site…and can assure you that no natives have been splitting anyone apart.

11:25AM: Harvey Levin himself rings me up to say: he distinctly remembers a story about a person whose plane crashed, survived the crash, but then some 'tribe'/the natives tied him to a tree and pulled him apart using some elaborate system of ropes. Apparently it was all over the news, sometime in the '60s – could I find out who it was? I told him that 'Africa' lends itself to such myths, and I'd be surprised if it were true, but he was heading to a meeting. So I assured him I'd put the word out via AIAC.

Natives and Tribals: do you know of such an incident?

I know of Leopold's people splitting people's hands off from their bodies in the Congo, and the US government doing some nasty things to natives from Afghanistan, Iraq, etc., but…

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers