Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 496

January 30, 2013

Watching the Africans Cup of Nations at an Ivorian restaurant in Harlem

Acting on a tip from an Ivorian diplomat on the best location to watch Les Éléphants play in NYC, we headed up to Harlem to catch the Côte d’Ivoire–Tunisia match early Saturday morning. New Ivoire is a 17-year-old, 24-hour restaurant on 119th street in a growing West African area of Harlem that is both frequented and owned by Ivorian taxi drivers. It has also been the de facto headquarters of Ivorian fans cheering on their team during this year’s Africa Cup of Nations.

We sat by the back next to the owner and enjoyed coffees and teas with sweetened condensed milk, kidney and liver beef sandwiches, and toasted baguettes with butter alongside more than 50 very enthusiastic and captivated orange-clad Ivorian fans. Sadly, we were a bit too early to try their foutou banane, Côte d’Ivoire’s national dish, and the name of a popular coupé décalé dance.

Côte d’Ivoire scored first through a Gervinho strike twenty minutes in, sending the standing-room only crowd in Harlem into an absolute frenzy as this video, below, shows:

Tunisia later found their stride in the second half and threatened to level the score a few times during some crafty attacks that visibly frayed the Ivorians’ nerves. Then, in the 87th minute, Yaya Toure drilled home a second for Les Éléphants that instantly changed the mood at New Ivoire from cataclysmic nervousness to joyous ecstasy. The patrons jumped out of their seats, sang, danced, cheered, and embraced each other knowing victory was theirs.

Didier Ya Konan’s neat finish inside the box three minutes later gave Côte d’Ivoire their icing-on-the-cake third goal and the crowd in Harlem even more reasons to celebrate their assured progression to the next round of the very tournament that their golden generation of players has perpetually come up short at.

As the final whistle blew, the wait staff, cooks, and patrons continued to sing and dance as we thanked them for their hospitality and exited the warm and welcoming uptown Ivorian experience back into the frozen New York City air.

* The post is co-written with Owen Dodd and Rob Navarro, who between the 3 of them took the photos. A project started in a graduate class on global soccer taught by Sean Jacobs at The New School, we attempt to watch football across New York City and to blog about it at our tumblr, Global Soccer, Global NYC, too

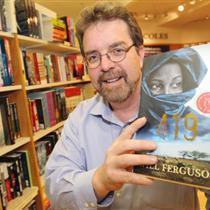

Novelist Will Ferguson wrote a novel about 419 scams. He won an award for it. Is it a good read?

To be 419′ed is to be fooled. Duped. Swindled. At least that’s the meaning as far as Nigerian slang is concerned — of which this book has plenty on offer. The question is: does Will Ferguson’s Giller-winning novel deliver on the award hype, or does it 419 us? The answer is… yes. “419″ begins when a hapless Calgarian falls for a Nigerian email scam (for more info, see your spam folder from ten years ago). He subsequently ruins his finances and offs himself, setting in motion a quest that will see his surviving daughter, Laura, attempt to find out who is responsible.

From the beginning, the novel flits back and forth between Laura picking up the pieces in Canada and a host of Nigerian characters whose roles in the story will not become clear until the climax. With Nnamdi (a young man from the oil-rich Niger delta ), Amina (a troubled girl from the Muslim north), and Winston (an educated city boy turned scammer) we have three intertwining narratives that provide something of a portrait of contemporary Nigeria. The stark differences between north and south. The oil-slicked hellhole of the southern delta. Rural poverty. Urban chaos. More on this depiction later.

This fast-paced movement is one of the novel’s strengths. It doesn’t give you time to get bored, because the scenes aren’t overdrawn — particularly at the beginning. Indeed, with 129 chapters, the average length of each is only three pages (1,000 words), and many are as short as a paragraph. One page you’re in a Calgary food court, the next you’re walking through ash under the Sahelian sun, and the next you’re motorboating through an oil-drenched mangrove forest on the Bight of Bonny.

That being said, there are some slack parts. In particular, a 32-page section chronicling Nnamdi’s coming of age and the gradual environmental destruction of the Niger delta.

It’s not that the topic doesn’t merit a 10,000-word treatment. A subject like that is worth a book of its own, or several. The real problem, rather, is the Nigerian narratives are slightly didactic.

Ferguson has apparently never been to Africa, and quite frankly, it shows. While he has a real talent for rendering rich scenes and bringing the Nigerian environment to life, my enjoyment of the narrative was brought low by unlikely dialogue that would be more at home in a political science text than in the mouth of a real human being.

Let’s look at an example. It’s taken from a section about how Shell’s local development projects were little more than cynical PR stunts:

“The health-care clinic has no roof!” people shouted at the members of the larger ibe. “How much dey payin’ you?”

“Not stolen, taken. That clinic was empty. No nurse, no doctor. Why let the roof just sit over nothing like that?”

“A nurse comes!”

“Once a year! If that. Once a year from Portako, nurse be coming to inject us with inoculate for everything except oil…” (p. 178)

This kind of dialogue is parachuted into the narrative in such an instructional fashion that it robs the characters who speak it of any personality worth noticing. These characters’ purpose seems only to convey information about injustice in Nigeria, not to speak like normal human beings. And in a novel you must always prefer true character over information. If I want to bone up on Nigerian history, I’ll hit the library.

There are a number of sections like this throughout the book that weaken the Nigerian side of the narrative. They often take the form of Character A making small talk about his people’s sacred beliefs and customs with Character B, the two of whom have just met (see sections 78 & 80).

Maybe this won’t bother readers who aren’t familiar with Nigeria—you might be intrigued by the descriptions of water gods and creation myths and so forth—but Africans just don’t talk like this. Nobody does. It would be like if you bumped into someone from Finland and the first thing the two of you discussed were your cosmological beliefs.

I can see the process that led to this. I can imagine exactly how it happened. Perhaps it went something like this: the writer has never been to Africa. The writer wants to do well, so he studies up—reading, talking to people, surfing the net. He accumulates a lot of information. What an interesting place, Nigeria! What fascinating cultures! What colour that would bring to the story! And how educational it will be!

This is a laudable impulse. People should know more about Nigeria. But it leads to two problems. The first is that it pushes the African characters toward objectification — their role in the story is to convey difference, exoticism. And the world they inhabit is the opposite of ours: hot to our cold, polluted to our clean, impoverished to our affluent.

And of course this is all true. These are, so to speak, the facts. Most Nigerians are poor. Yet as always in literature, it is a question of emphasis. And the emphasis in 419 is too often on strangeness.

In that sense it parallels colonial ethnography—a catalogue of the unknown, a juxtaposition of here and there. Yet serious students of Africa have moved on. These days they’re more interested in Africans as people rather than Africans as Africans, if you see the difference. In 419, while the main Nigerian characters are multifaceted, they are too often animated by didactic tendencies that erode their position as people. They become, rather, spokespeople.

This leads to the second problem, which is that this sort of writing undermines the believability of the characters. Again, people don’t neatly lay out their worldviews, philosophies, and social problems to near-strangers — unless those strangers are, perhaps, anthropologists. Not that I’m a great expert, but no African I’ve ever met talks that way.

Am I being too picky? Perhaps. But this may be a good way to find out: pick up any famous Nigerian novel — Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, Ben Okri’s The Famished Road, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie‘s first, Purple Hibiscus–and see if the characters speak like a drama scene from an International Development Studies class. If memory serves me right, they don’t.

Predictably, this made the Canadian side of the book the most enjoyable. Ferguson’s protagonist, Laura, is likeable and well-drawn, and when she gets on the trail of the conmen responsible for her father’s death, you can’t help but smile. Pretty gutsy for a timid copyeditor from Calgary.

The pace of the novel is snappy, too, and when I think of this book the phrase “Good to read on an airplane” comes to mind. Maybe it’s because it’s easily digestible — the sentences, paragraphs, and chapters are all short and clear. The story is solid. 419 is a very respectable piece of entertainment.

And this brings us back to the Giller question, because winning big prizes always conjures up fun terms like “literary gravitas,” along with the question of whether the book is not just a heart-pounding thriller but also a contribution to letters.

Heart-pounding thriller? Page-turner? More or less. I must admit the final fifty pages had me revved up. The story does have a kick to it.

A contribution to letters? Mmm … no. For one thing, the prose isn’t what I’d call lyrical. ‘Serviceable’ is the word that comes to mind. ‘Satisfactory.’ It gets the job done—and, to be fair, it does sparkle in places. But I don’t think there is a remarkable literary voice to be found in 419. I wasn’t transported to emotional heights by Ferguson’s phraseology. I wasn’t in awe of his sentences. I didn’t feel I was swimming in his words, the way I do when reading Julian Barnes or Howard Jacobson. And whatever you might say about the subject matter or plots of these recent Booker prize winners’ novels, their mastery of prose isn’t in question.

With Ferguson, on the other hand, it was hit and miss. Maybe that brings us back to the stilted dialogue.

And maybe that was never Ferguson’s intention — to write a ‘literary’ novel. If so, it would be unfair to judge him by those standards. But ultimately all I have to guide me is my taste. And in my opinion, this is not an outstanding novel. Decent, but not outstanding.

My sense is it will appeal more to the lover of thrillers and popular fiction than to the ‘literary’ type. If you aren’t so demanding of dialogue, and you don’t mind Ferguson’s over-exotic bent, you may really love 419.

But if you’re the person who likes picking up the latest Booker and Giller winners to see what passes for literature these days, prepare to feel lukewarm.

* This is an edited version of a review by Robert Nathan, a PhD student in African history at Dalhouse University in Canada.

Novelist Will Ferguson wrote a novel about 419 scams. He won an award for it. How good’s the book really?

To be 419′ed is to be fooled. Duped. Swindled. At least that’s the meaning as far as Nigerian slang is concerned — of which this book has plenty on offer. The question is: does Will Ferguson’s Giller-winning novel deliver on the award hype, or does it 419 us? The answer is… yes. “419″ begins when a hapless Calgarian falls for a Nigerian email scam (for more info, see your spam folder from ten years ago). He subsequently ruins his finances and offs himself, setting in motion a quest that will see his surviving daughter, Laura, attempt to find out who is responsible.

From the beginning, the novel flits back and forth between Laura picking up the pieces in Canada and a host of Nigerian characters whose roles in the story will not become clear until the climax. With Nnamdi (a young man from the oil-rich Niger delta ), Amina (a troubled girl from the Muslim north), and Winston (an educated city boy turned scammer) we have three intertwining narratives that provide something of a portrait of contemporary Nigeria. The stark differences between north and south. The oil-slicked hellhole of the southern delta. Rural poverty. Urban chaos. More on this depiction later.

This fast-paced movement is one of the novel’s strengths. It doesn’t give you time to get bored, because the scenes aren’t overdrawn — particularly at the beginning. Indeed, with 129 chapters, the average length of each is only three pages (1,000 words), and many are as short as a paragraph. One page you’re in a Calgary food court, the next you’re walking through ash under the Sahelian sun, and the next you’re motorboating through an oil-drenched mangrove forest on the Bight of Bonny.

That being said, there are some slack parts. In particular, a 32-page section chronicling Nnamdi’s coming of age and the gradual environmental destruction of the Niger delta.

It’s not that the topic doesn’t merit a 10,000-word treatment. A subject like that is worth a book of its own, or several. The real problem, rather, is the Nigerian narratives are slightly didactic.

Ferguson has apparently never been to Africa, and quite frankly, it shows. While he has a real talent for rendering rich scenes and bringing the Nigerian environment to life, my enjoyment of the narrative was brought low by unlikely dialogue that would be more at home in a political science text than in the mouth of a real human being.

Let’s look at an example. It’s taken from a section about how Shell’s local development projects were little more than cynical PR stunts:

“The health-care clinic has no roof!” people shouted at the members of the larger ibe. “How much dey payin’ you?”

“Not stolen, taken. That clinic was empty. No nurse, no doctor. Why let the roof just sit over nothing like that?”

“A nurse comes!”

“Once a year! If that. Once a year from Portako, nurse be coming to inject us with inoculate for everything except oil…” (p. 178)

This kind of dialogue is parachuted into the narrative in such an instructional fashion that it robs the characters who speak it of any personality worth noticing. These characters’ purpose seems only to convey information about injustice in Nigeria, not to speak like normal human beings. And in a novel you must always prefer true character over information. If I want to bone up on Nigerian history, I’ll hit the library.

There are a number of sections like this throughout the book that weaken the Nigerian side of the narrative. They often take the form of Character A making small talk about his people’s sacred beliefs and customs with Character B, the two of whom have just met (see sections 78 & 80).

Maybe this won’t bother readers who aren’t familiar with Nigeria—you might be intrigued by the descriptions of water gods and creation myths and so forth—but Africans just don’t talk like this. Nobody does. It would be like if you bumped into someone from Finland and the first thing the two of you discussed were your cosmological beliefs.

I can see the process that led to this. I can imagine exactly how it happened. Perhaps it went something like this: the writer has never been to Africa. The writer wants to do well, so he studies up—reading, talking to people, surfing the net. He accumulates a lot of information. What an interesting place, Nigeria! What fascinating cultures! What colour that would bring to the story! And how educational it will be!

This is a laudable impulse. People should know more about Nigeria. But it leads to two problems. The first is that it pushes the African characters toward objectification — their role in the story is to convey difference, exoticism. And the world they inhabit is the opposite of ours: hot to our cold, polluted to our clean, impoverished to our affluent.

And of course this is all true. These are, so to speak, the facts. Most Nigerians are poor. Yet as always in literature, it is a question of emphasis. And the emphasis in 419 is too often on strangeness.

In that sense it parallels colonial ethnography—a catalogue of the unknown, a juxtaposition of here and there. Yet serious students of Africa have moved on. These days they’re more interested in Africans as people rather than Africans as Africans, if you see the difference. In 419, while the main Nigerian characters are multifaceted, they are too often animated by didactic tendencies that erode their position as people. They become, rather, spokespeople.

This leads to the second problem, which is that this sort of writing undermines the believability of the characters. Again, people don’t neatly lay out their worldviews, philosophies, and social problems to near-strangers — unless those strangers are, perhaps, anthropologists. Not that I’m a great expert, but no African I’ve ever met talks that way.

Am I being too picky? Perhaps. But this may be a good way to find out: pick up any famous Nigerian novel — Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, Ben Okra’s The Famished Road, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie‘s first Purple Hibiscus–and see if the characters speak like a drama scene from an International Development Studies class. If memory serves me right, they don’t.

Predictably, this made the Canadian side of the book the most enjoyable. Ferguson’s protagonist, Laura, is likeable and well-drawn, and when she gets on the trail of the conmen responsible for her father’s death, you can’t help but smile. Pretty gutsy for a timid copyeditor from Calgary.

The pace of the novel is snappy, too, and when I think of this book the phrase “Good to read on an airplane” comes to mind. Maybe it’s because it’s easily digestible — the sentences, paragraphs, and chapters are all short and clear. The story is solid. 419 is a very respectable piece of entertainment.

And this brings us back to the Giller question, because winning big prizes always conjures up fun terms like “literary gravitas,” along with the question of whether the book is not just a heart-pounding thriller but also a contribution to letters.

Heart-pounding thriller? Page-turner? More or less. I must admit the final fifty pages had me revved up. The story does have a kick to it.

A contribution to letters? Mmm … no. For one thing, the prose isn’t what I’d call lyrical. ‘Serviceable’ is the word that comes to mind. ‘Satisfactory.’ It gets the job done—and, to be fair, it does sparkle in places. But I don’t think there is a remarkable literary voice to be found in 419. I wasn’t transported to emotional heights by Ferguson’s phraseology. I wasn’t in awe of his sentences. I didn’t feel I was swimming in his words, the way I do when reading Julian Barnes or Howard Jacobson. And whatever you might say about the subject matter or plots of these recent Booker prize winners’ novels, their mastery of prose isn’t in question.

With Ferguson, on the other hand, it was hit and miss. Maybe that brings us back to the stilted dialogue.

And maybe that was never Ferguson’s intention — to write a ‘literary’ novel. If so, it would be unfair to judge him by those standards. But ultimately all I have to guide me is my taste. And in my opinion, this is not an outstanding novel. Decent, but not outstanding.

My sense is it will appeal more to the lover of thrillers and popular fiction than to the ‘literary’ type. If you aren’t so demanding of dialogue, and you don’t mind Ferguson’s over-exotic bent, you may really love 419.

But if you’re the person who likes picking up the latest Booker and Giller winners to see what passes for literature these days, prepare to feel lukewarm.

* This is an edited version of a review by Robert Nathan, a PhD student in African history at Dalhouse University in Canada.

January 29, 2013

Songs for the Atlas Lions of Morocco (or Afcon 2013 Playlist Playlist N°5)

Despite high hopes, Morocco’s Atlas Lions crashed out of Afcon 2013, but that didn’t prevent young Moroccans from bumpin’ and groovin’ to radio pop. First up is the internationally renowned and veteran Algerian crooner, Khaled, known for hits like “Aicha” and “Didi.” In late 2012, Khlaed released a new album with a new single, “Hiya Hiya,” which features American rapper/songwriter Pit Bull.

Then’s there’s Rihanna’s “Diamonds.” We sure hoped that our national team would “shine bright like a diamond” at this year’s Afcon tournament. Rihanna’s melancholic song reflects our dashed hopes of football glory. Alas, maybe at next year’s World Cup we’ll be more successful (yeah right).

“Tombée pour elle” (fell for her), is an R&B song by Booba, a Half Senegalese and half French artist who has been rapping since the mid-1990s.

Yes, Britney Spears & Will.i.am’s “Scream and Shout.” Despite her mental meltdown a few years ago, Moroccan music fans have not given up on Britney. Teaming up with Will.I.Am (from the Black Eyed Peas), this Gangnam Style-like hit is ruling Morocco’s airwaves and club scene.

Moroccan rap artist, Fnaire (and Soprano, featured on the song), hails from the city of Marrakessh. Together they perform what they coin as “traditional rap”. They mix tradition music (like Chaabi music) with hip hop, and infusing it with lyrics about social and political issues that resonate among Moroccan youth.

* Youssef Benlamhih blogs and tweets about international affairs.

The trouble with Angola

Like many Angolans on Sunday I was forced to eat my share of humble pie and admit the superiority of Cape Verde’s national football team, which, through sheer grit and determination, qualified their country to the quarterfinals of the African Cup of Nations at their first time of asking. Thus the tiny island nation of Cape Verde is now one of the 8 best teams on the continent. The Cape Verdeans played with a passion and will to win that has been conspicuously absent from the Angolan outfit since the opening match against the Moroccans. Watching Angola and Cape Verde play after having watched the Ivorians and to a lesser extent the Togolese beat their opposition the previous day highlighted just how far Lusophone football has to progress in order to challenge the continental giants; but the gulf in class between the Angolans and the Ivorians for example showed just how far apart we are in pure footballing skills. But also a matter of politics.

Clearly a team that played the way the Palancas Negras played against South Africa and Cape Verde has some much deeper structural issues that need to be examined. Perhaps we are not yet ready to progress beyond the quarterfinals. Cape Verde showed us that we are better off focusing on progressing from the group stages instead.

Condemnation of the Palancas Negras was swift and brutal amongst Angolans on both Facebook and Twitter. They were outraged at their team but many were also magnanimous enough to applaud Cape Verde on their brilliant achievement. Many questioned the $9 million that was spent on the Palancas Negras’ preparation. There was also widespread discontent aimed at FAF (Angolan Football Federation) and even the Minister of Youth and Sports for what many Angolans perceive as misguided sports policies and chronic underinvestment in the sector. Among the most common complaints is the complete lack of investment in youth football, footballing schools and youth development in Angola.

Many questioned why it seemed that Angolan football team owners have enough money to bring ageing stars into the country (such as Rivaldo to Kabuscorp) but don’t seem to care about developing their own clubs’ youth structures. For a team in its seventh appearance in the Nations Cup finals, a lot more was expected of them. Fans noticed that the team hasn’t built on its 2006 success, when the Palancas reached the World Cup.

Angola is used to being the Big Brother among Africa’s Lusophone nations: our petrodollars and military might obfuscate our many shortcomings. So Cape Verde’s victory over Angola was met with huge appreciation not just with Cape Verdeans but also among Mozambicans.

Cape Verde, once again, taught us a lesson.

For all our petrodollars, economic superiority, flashy skyscrapers and shiny Porsche Cayennes, for all of our millions spent in preparation for this Afcon, Cape Verde simply showed us that sometimes less is more. They scrounged together some funds to be able to put a team into the competition, had a few friendlies here and there and then quietly set about their work. Their footballing leadership didn’t make any lofty promises of a semi-final finish, unlike Angola’s. Instead, the Blue Sharks showed humility and an uncanny ability to stifle the more potent attacking strike force of their superior rivals.

But it isn’t just about football.

The governments of Cape Verde and Angola couldn’t be more different. Cape Verde’s investment in their education and health sectors put Angola’s to shame, and the Atlantic archipelago is ahead of Angola in almost every social indicator imaginable, including HDI. Their governance, rule of law, regular elections, and respect for their strong institutions are among the best among Lusophone countries and certainly better than many African states, including, of course, Angola. When a rival political party wins an election in Cape Verde, the transfer of power is peaceful and civil.

In the aftermath of the Lusophone clash, Angolan journalist Reginaldo Silva used Facebook to post a quote from Cape Verdean Prime Minister José Maria Neves to an Angolan newspaper: “O nosso petróleo é a boa governação” (Our oil is good governance).

Songs for Chipolopolo (or Africa Cup of Nations Playlist N°4)

By Charles Mafa*

By Charles Mafa*

It’s death or glory today for defending champions Zambia, who must beat Burkina Faso to make it to the quarter-finals. Anything less will be a major disappointment. Just in case the Chipolopolo boys need a confidence booster ahead of the big match, and so that they remember what this means to the fans back home, here’s our playlist of top Zambian tunes in praise of their heroes.

We start with “Vuvuzela” by Shimba Boyd, a very captivating song urging the Zambian team to show them how to play the game. A popular hit in bars, taverns and night clubs and also on both radio and television especially when Zambia is playing.

Next up it’s “Mad Chipolopolo”, a song by MADD featuring Rearn thanking God for the beautiful colours of Zambia. Orange (mineral wealth), green (vegetation) red (blood during independence) and black for the people.

Here’s MC Wabwino with “Chipololopolo” (a popular title this). Mkunsha Chembe, the elephant of Zambian music, doesn’t want to be left out as he sings Chipolopolo. (It’s Chipolopolo if you want to dance!).

If your enthusiasm hasn’t been stoked, it will be when you’ve heard Leo Muntu with “Zambia Let’s Go”. A popular track in bars, on radios and television. Top marks for dancing.

We’ll leave it with MC Wabwino to round things off. Here’s “Ona Kayako Chipolopolo”, another beauty from last year praising the dribbling skills of the Zambian players (listen for the name-checks).

* Charles Mafa is an award-winning investigative journalist based in Lusaka, Zambia. His personal website is The Investigator.

Timbuktu: It’s like a library has burned

News came yesterday, violent, rotten news. It’s been a steady rhythm from Mali, a country that has already suffered too much. But there’s something brutal in the news that Salafist fighters burned hundreds of rare manuscripts, some of them unique and centuries old, before leaving Timbuktu to French paratroopers.

Years ago, one of Mali’s great intellectuals, Amadou Hampaté Bâ, famously told us that in Africa “when an old man dies, a library has burned.” Hampaté Bâ celebrated a traditional Africa, one marked by its orality. A generation of scholars has rebelled against that idea, considering it a misrepresentation, even a liable. The manuscripts of Timbuktu were their best argument that Africa had more than stories to tell; it had a textual tradition to share. Today’s news tells us that that too is lost.

But let’s not move too fast. The manuscript tradition of the southern Sahara was never captured by Timbuktu alone. Timbuktu is a synecdoche; it is only a part that represents the whole. People across the Sahara hold their own manuscripts, sometimes carefully preserved in tin trunks or leather bags, sometimes buried in a tent’s sand floor. Timbuktu might have held the richest collections, but even there, several families have their own libraries. The scion of one of them had the foresight to transport his collection to Bamako months ago. Perhaps others followed suit.

Another reason for hope: news reports show us film of empty shelves. We don’t know that the Salafists—or someone—hadn’t removed those priceless papers, or at least some of them, hoping to sell them in the future … or maybe read them? Would they read there that “there is no compulsion in religion”? Perhaps, but they would only need the Qur’an for that.

Other stories haunt me as I think about this one. An image, one I can’t find now but can’t forget, of very young fighters, too young to grow the Salafists’ beards, dead in the sand. The rapes and forced marriages, carried out by the Salafists, before them by the Tuareg separatists of the MNLA. The low-caste women raped by soldiers, “sources say.” The young man telling a journalist that he couldn’t find his friend, a light-skinned man in Sevaré at the wrong time. Soldiers took him away. Was he burned alive, or thrown down a well? It doesn’t matter. That story is only the latest; it won’t be the last.

Can we reverse Hampaté Bâ? He wanted to express a tragedy he’d lived, the loss of knowledge under colonial rule. We want to express our own. We can mourn what has been lost in Timbuktu. But what stops us from saying that “When a library burns, it’s like a girl was violated?” Or, “When a library burns, it’s like a young man has died?” They lie there, too, in the sand.

Postscript: Months ago, some of Africa’s leading intellectuals drew attention to the peril the manuscripts faced, and I wrote about it here, on Africa is a Country.

And I still reject the fairytale.

Burkinabe Rapper Art Melody’s Playlist For Les Étalons (Afcon 2013 Playlist N°3)

By Mamadou Konkobo (aka Art Melody)*

By Mamadou Konkobo (aka Art Melody)*

Later today we play against Zambia for a place in the quarterfinals of the African Cup of Nations. We are first in our group, we just need to handle it well. Zambia has to win, we need at least a draw. I’m convinced we can qualify. Let’s just remember: ”Ensemble soutenons les étalons à la conquête du ballon rond” (together, let’s support the Etalons in their conquest of the round ball”). Here’s some songs to build morale ahead of the clash.

Black So Man’s “Les étalons” was the anthem in the 1998 Afcon, but shortly after Black So Man had an accident, he passed away before attending the cup. To this day it remains the national soccer anthem, there are many other ones, but this is the best.

Victor Demé is one of the most popular Burkinabé artists, in recent years he has managed to raise Burkinabé music to an international level, he has won awards and is the artist who tours the most.

Black Marabouts’ “A qui la faute” is a song that talks about everyday life for the Burkinabé people. In the song the group asks people: whose fault is it if we can’t heal, if we can’t improve how our society is? It asks who is responsible, it reminds everybody of their own responsibilities, teachers going out with students, youths who choose not to work, but rather give into petty crime and prostitution, leaders who prefer to buy cars and build houses rather than take care of the country. I really dig that song. The group has since split up, but Black Mano had a really ill flow.

WAGA 3000: “Sak Sin Paode”. Accept what is little, in the hopes of getting more. Or in other words, you have to accept your condition if you hope to grow. It’s a Mooré proverb, in the song we mainly talk about humility, how we never cease to learn, and how we must never stop respecting one another.

Orchestre Volta Jazz’s “Djougou Malola”. “Enemies are ashamed.” When somebody gets jealous, don’t mind them, work and move forward, you’ll eventually rise and they’ll remain in their own shame. Volta Jazz is one of those mythical 1970s groups. Until Florent Mazzoleni released his book about the history of Burkinabé music, very few were aware of them, but now there is a kind of renaissance, they are back in the studio working on a new album. Today Mustapha Maiga, the lead singer and saxophone player, is heading this renaissance.

And Amadou Ballaké is another one of the major figures in Voltaic music — that’s how it used to be called here, Haute Volta! He rose to fame in the 1970s, and is still around! He was a member of Africando for some time, and has done a lot for Burkinabé music across the decades.

* Art Melody is a rapper from Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso.

January 28, 2013

British TV news airs footage refuting South African police claims about murdered Marikana miners. Where was the South African media?

Five months after the Marikana Massacre in South Africa, footage of police action at the ‘killing koppie‘ ["hill"] has finally reached the public. This footage somewhat predictably wasn’t brought to our attention by the local media, who have long since moved on to other things since the Marikana story stopped selling. Rather, it was Channel 4 in the United Kingdom who brought this footage to light. Why then did it take so long for the footage to reach us and why did it reach us in such a manner? Was it deliberately suppressed or is there a police whistleblower? One can reasonably speculate that the police were ordered to delete the evidence collected on their mobile phones in the aftermath of the massacre, but surely more footage has survived the culling of a cover-up.

Five months after the Marikana Massacre in South Africa, footage of police action at the ‘killing koppie‘ ["hill"] has finally reached the public. This footage somewhat predictably wasn’t brought to our attention by the local media, who have long since moved on to other things since the Marikana story stopped selling. Rather, it was Channel 4 in the United Kingdom who brought this footage to light. Why then did it take so long for the footage to reach us and why did it reach us in such a manner? Was it deliberately suppressed or is there a police whistleblower? One can reasonably speculate that the police were ordered to delete the evidence collected on their mobile phones in the aftermath of the massacre, but surely more footage has survived the culling of a cover-up.

Four months after the story of the killing koppie was brought into the mainstream media (working off the research of a group of University of Johannesburg sociologists) by Greg Marinovich and South African web-based publication Daily Maverick, cellphone footage taken by police at the scene of the massacre appears to provide further evidence to support Marinovitch’s claims of ‘execution style killings’.

The highly disturbing footage shows police moving around, taking potshots, joking about killings and even boasting about shooting one “motherfucker” ten times, despite the easily ignored plea of one officer to not shoot the “bastard”. It shows numerous corpses around the area with police idly watching over, while the wounded writhe in agony.

It gives us a first person perspective of the shooter with the cellphone showing us the gun of the person filming it, as if it was a video game or a action movie. It blurs the line between the hyper-reality of a video game and the grotesque of a snuff film.

One scene shows two workers attempting to wriggle away from the police, a hopeless attempt as the police are standing around them, looking somewhat amused at their desperation. The police’s tone, although barely audible, is gung-ho, exhilarated at the possibility of finally unleashing their pent-up rage at the bastards.

It seems that there is more footage to come that escaped what can only be described as one of the most poorly executed cover-ups in law enforcement history. It even surpasses the old death by soap stories of our previous political regime in stupidity. All the facts were there. The problem was nobody really bothered to look beyond press statements and the original television footage. Nobody initally bothered to speak to the miners except for a few radicals and, easily ignored by virtue of their divergence from the range of acceptable opinion.

The myth of Marikana as self-defense should by now be conclusively consigned to the dung heap of historical perjury. Instead Police chief Riah Phiyega’s comments are highly revealing, to say the least: “All we did was our job, and to do it in the manner we were trained.” And to further illustrate how their police accomplished their job so well: “Whatever happened represents the best of responsible policing. You did what you did because you were being responsible. You were making sure that you continue to live your oath.”

Surely this counts as an official endorsement of the massacre?

Perhaps the most tragic fact of Marikana was not the killing, but the muted response of the South African public in the aftermath of the killings. No mass demonstrations, no real collective outrage, mainly just passive acceptance and in some cases support for state violence. Not that any of that collective apathy stopped the mass strike wave which took hold across the platinum belt.

It remains to be seen if such visceral evidence of the atrocities which took place that day will spark a more heated reaction, but so far the media response at least is quite tame, treating it still as yesterday’s news not worthy of a renewed focus on the events of that day.

Maybe, just maybe, it might inspire a collective critical retrospective on what went wrong in the coverage of the massacre and a future boycott of press statement journalism. However, there is probably a better chance of retreating into the fortress of objectivity.

In the meanwhile, the story of Marikana continues. Most workers at Lonmin’s platinum mines apparently have not received their promised 22% raise and there are numerous reports of disappearances and continued intimidation with many workers having simply disappeared and remaining unaccounted for. As the recent news of the mass retrenchments at Amplats show us, the mineworkers struggle is far from over.

My Favorite Photographs N°11: Jide Odukoya

Nigerian photographer Jide Odukoya’s portfolio offers an exceptional insight into the social fabric of Lagos. His Facebook page documents fashion events, open mic ‘happenings’ and weddings, while his official website reveals focused street photography series, such as ‘ADay in the World (Creek Road Market)’, ‘Kids in Makoko’, ‘Lazy Obalende’ or ‘The Business of Worship’. As part of our “favorite photographs” series, we asked Odukoya to pick his 5 favorite shots, and share some words about how and where the images were made.

Nigerian photographer Jide Odukoya’s portfolio offers an exceptional insight into the social fabric of Lagos. His Facebook page documents fashion events, open mic ‘happenings’ and weddings, while his official website reveals focused street photography series, such as ‘ADay in the World (Creek Road Market)’, ‘Kids in Makoko’, ‘Lazy Obalende’ or ‘The Business of Worship’. As part of our “favorite photographs” series, we asked Odukoya to pick his 5 favorite shots, and share some words about how and where the images were made.

Recently I was selected to be a part of the Invisible Borders Trans-African Photography Project, which involved photographers, visual artists and film makers. Every year this collective welcomes new participants who travel through five to six countries in Africa all together in a van with the aim of telling African stories (by Africans) and building inter-relationships amongst participating artists and artists in countries visited. This year we travelled from Nigeria through Cameroon and Gabon before heading back to Lagos, Nigeria. The image above is one of the photographs I took in the process of passing through the muddy border village of Ejumoyock. It shows local villagers trying to pull out our van at Ejumoyock on our first night in the rain forests of Cameroon. I particularly like this photograph because it reminds me of the first of four nights we spent here trying to pull our van across roughly ten kilometres of severely muddy forest pathways. It was a tough experience for me; we slept in the van for five days and engaged only with the nearby village boys and the forest ants who kept us company through the night in the cold forest. These boys had just found a new job of helping stuck vehicles out of the forest. Due to land issues between the Nigerian and Cameroonian governments, the road which connects the south of Nigeria to the west of Cameroon has been left unattended to for years. The contract had just been awarded to a Chinese construction company which just recently began working on the road. The scene is one I would never forget in a hurry.

The following image is one I really love from the series Nigerians in Libreville, a documentary I did in Gabon which explores the paradoxical stories of Africans living on African soil, but in countries other than their respective native countries. There have been reported incidents of xenophobic discrimination and socio-political nightmare. A number of Nigerians who fled Nigeria during the Biafran war are now resident in Gabon. There are also others who arrived travelling through a deadly sea in search of a promised greener pasture. Most would agree that the economy of Gabon is far better than Nigeria while some, entrapped in circumstances far beyond their control, feel there is no place like home. Their stories recount their experiences; the dangers of migrating through the sea, challenges of starting a new life in a francophone country, a frictional relationship with the authorities, and the threatening fear of returning back to their homeland as empty as when they came.

I met Daniel on the 4th day we got into Gabon while still doing a street walk round a nearby market close to where we stayed. He saw me with my camera and was happy. For the first time I met someone who understood English and I asked to take a shot. Libreville is a photophobic city and people would readily shy away at the sight of a camera. I got into conversation with Daniel and got to know he was also a Nigerian. He told me how he had been managing his small business as an ice cream seller and how he wished to return to Nigeria later in December. I later returned days after our first meeting to take this shot of him. Although content with his current work and status, he says it’s time for him to visit his homeland Nigeria since he left as a child 23 years ago.

As part of my daily work on the trip, I documented the daily lives of Gabonese on the country’s coast line. I came across this French man playing with the kids on the beach. This brings to mind the long-time relationship between France and Gabon, as noted by a Gabonese who said it’s much more difficult for somebody from a neighbouring country to come into Gabon than a visitor from France. Interestingly, it had been rather tedious for our team to get Visas into the country.

Next is one of my favourites from the Invisible Borders trip. While coming back from the trip, travelling several kilometres during the night through hilly and mountainous landscapes of Cameroon, we got to a village called Tiben as the day broke. Tiben has a very beautiful scenery and was very chilly with the clouds at sea level. I quickly grabbed my camera and ran down towards the hill. As I tried to capture the awesome spectacle, this girl appeared on my viewfinder out of nowhere. I was astonished! I never thought any human being could be living in that region, let alone a little girl.

French language proved a painful barrier as I tried to ask the girl some questions and have some small talk. She didn’t understand English either, I thought. She walked away. I now focused on the beautiful scenery. I am proud to be an African, living in a place called Africa.

It is hard to reflect objectively on the proliferation of Churches in Nigeria. There are many reasons for this, the major one being the manner in which spirituality has formed a sensitive layer in the subconscious of Christians, especially in the country’s southern parts. The proliferation touches on media, the economy, and social structure. Many have attributed this quest for a better life to underdevelopment and poverty, but it is difficult to assume this lies at the crux of the growth and prosperity of churches. When I began to photograph the evidences of Christian life in Port Harcourt (where I currently live), I wanted to discover the subtleties inherent in Port Harcourt’s Christianity. I was interested in the way invitations stood out, how church leaders (with varying titles) used their posters not simply as advertisement but as self-aggrandizement.

It bothered me to question how these churches, in their numbers, and with thousands of worshippers, struggled for space, credibility and relevance. Was it really a struggle? Was there some unity in the similarity of posters, of postures, of worship? I understood, immediately, that I was trying to capture a landscape that captures attention through words and images. Out of all the images, the one above particularly stands out as it appears to have been inspired by Prison Break, the popular American prison series.

* Jide Odukoya resides in Lagos, Nigeria. His website: http://www.jideodukoya.com.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers