Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 493

February 8, 2013

Ghanaian Hip-Hop Lyricist M.anifest Writes for Us: Laments of a Disappointed Ghana Black Stars Fan

Post by M.anifest*

Oh Ghana Black Stars! Again? Our time in the trophy-less wilderness just got a 3 year extension yesterday courtesy our neighbors to the north, Burkina Faso. This is how they repay us for supplying them with electricity (I kid).

31 years and counting…

Last week if you mentioned Black Stars you would find some of my countrymen throw around fancy terms such as “powerhouse,” “favorites,” “the team to beat,” “the Brazil of Africa” (my least favorite) and “four-time champions.” The Black Stars haven’t won a trophy the entire time I’ve been on planet earth so as far as I’m concerned we were champions in some ancient time period when black and white TV’s ruled and having a TV in itself was probably still just a luxury for the super-rich.

Unrequited love…

See I love the Black Stars more than any team in the world, despite many disappointments. That’s love you know – unconditional and a long hangover you can’t get rid of. I mean I even released a new single, “GH Baby”, earlier than scheduled to demonstrate my love and support. I just think it’s high time we get with the times and the exigencies of today’s football reality instead of drowning in the shadows of past glory. But we’re not the only ones. Did you see all those empty seats during non-South African matches? AFCON also needs to figure out how to get on a Charlie Sheen #winning streak in this modern football era. If Africans are tuning in into the English Premiership rather than AFCON then something’s gone terribly wrong with the marketing.

Changing Times…

Watching Cape Verde essentially dominate the Black Stars in the quarter finals was great for AFCON. Gone are the days when all these new entrants and marginal soccer nations would be so easy to write off. I mean, two decades ago I would have expected we would have scored enough goals to spell Cape Verde. Ethiopia too showed up big time in the group stages. Both these sides were great to watch as much as the former was a thorn in the side of my team till we overcame them in a not-so-convincing 2-0 win. Sidebar lesson for AFCON/CAF: You’re bringing new exciting stories and audiences into the tournament. Give it as much hype as possible and get folks interested in seeing what the fuss is about.

Upsets, Referees, and Kung Fu tackles…

The Côte d’Ivoire versus Ghana final that never was and then the Nigeria versus Ghana final that never was were both great outcomes for objective viewers but a total pain in the side of those of us supporting our teams – the so-called favorites. Despite the referee being our 12th player versus the Burkinabe we still got punked in penalties. How bad does that suck eh? Well at least the referee was not as bad as the one who officiated the Togo versus Tunisia match. Lesson for Black Stars: the gap is closing between the best and the rest. Bring your A-game or get embarrassed.

All in all…

I enjoyed AFCON 2013. My heart’s not in it anymore. I will watch the final of course but you won’t catch me wasting my time on the third place match; a match which I think should be eliminated from future competitions all together. I mean, it’s a torturous waste of time for players and fans. No?

Shout out to all my folks on Twitter who made Afcon even more fun. To the person that went streaking during the Ethiopia-Burkina Faso match for a good laugh. And here’s to hoping next tournament is even better with a more exciting and less out of touch opening ceremony. No shots.

* M.anifest is an internationally acclaimed and brilliant lyricist from Accra, Ghana.

Burkina Faso’s match-fixer coach calls himself “the Lance Armstrong of football” and wants to win Afcon for Blaise Compaoré

Zambia’s victory in last year’s Africa Cup of Nations was a great story, and one that even the crustiest of cynics could get behind. A team returned to the site of the national tragedy in which their fathers’ wonderfully talented generation of footballers were killed, and won the trophy against overwhelming odds. They sung in unison as the emotional penalty shootout unfolded, and when the celebrations began, the coach picked up an injured player and carried him across the pitch to his jubilant teammates. What wasn’t to like?

Zambia’s victory in last year’s Africa Cup of Nations was a great story, and one that even the crustiest of cynics could get behind. A team returned to the site of the national tragedy in which their fathers’ wonderfully talented generation of footballers were killed, and won the trophy against overwhelming odds. They sung in unison as the emotional penalty shootout unfolded, and when the celebrations began, the coach picked up an injured player and carried him across the pitch to his jubilant teammates. What wasn’t to like?

Burkina Faso are this year’s Zambia. A footballing minnow that have shocked the great names of African football with a series of audacious, spirited displays and have made it all the way to the final, overcoming great adversity along the way. What’s not to like? Well, they’re coached by one Paul Put, a sunburnt Belgian who is one of a small handful of coaches to have been banned from football for match-fixing. He calls himself “football’s Lance Armstrong” (half-scapegoat, half-whistleblower, apparently), but if he’s expecting the call from Oprah it could be a long wait. And with revelations this week of the massive scale of match-fixing across the global game (yes we’re looking at you South Africa Football Association), sympathy for scapegoats is running low. Maybe this will turn into a great redemption story for Put, but we’ll take some convincing.

Not only that, but the man misses no opportunity to genuflect publicly to Burkina Faso’s de facto life president Blaise Compaoré, best known for murdering Thomas Sankara (“an accident”), shit-stirring across the continent while posing as some kind of peacemaker, and presiding over a lurch to the right that has enabled him and a tiny corrupt elite to amass great wealth at the expense of ordinary people (let’s see how long those term-limits last). Speaking to the international press, our man Paul Put described Les Etalons quarter-final victory over Togo as a “birthday present” to Compaoré (apparently the players, most of whom have never known another president, were “extra-motivated” by the fact that they were playing on Blaise’s 62nd birthday).

Let’s hope the Stallions are playing for Sankara on Sunday.

Still, whatever you say about the man, he’s done a remarkable job with this Burkina Faso side, which lost every game it played in the last Afcon. Tactically, he hasn’t made a wrong decision all competition and the team have been a joy to watch throughout, even after the loss of their wonderful forward Alain Traoré to injury. Strong at the back and fluid and dangerous in attack, Put has clearly filled his players with enormous belief, and their hugely impressive captain Charles Kaboré said as much after the Ghana game.

That semi-final is a game I will not forget, one of the best in any international competition in recent years. More than anything I will remember Jonathan Pitroipa: juggling the ball, dancing around defenders, surging towards goal every chance he got and playing always with a blend of showmanship and generosity that is so rare to see from anyone who is so much their side’s star player. He seemed to have a stamina beyond anyone else out there, and as nerves and cramp set in all around him, he kept on tormenting the Black Stars and looked fresh for another 120 minutes on the painted sand of Nelspruit. Events like the Nations Cup are the great stages on which sporting history is made and there is nothing in football like watching a great talent make that stage their own.

Pitroipa’s was a performance for the ages, and if those clowns at CAF (which has, don’t forget, its own notoriously corrupt life president in Issa Hayatou) don’t rescind the red card and let him play in the final, they will have robbed their showpiece game of the player of the tournament.

I haven’t come across a Ghanaian fan, shellshocked as they are, who wasn’t appalled by referee Jdidi’s alarming bias throughout the game and convinced that Burkina Faso should have had that last-minute penalty. Maybe Paul Put was right about match-fixing being a massive problem at all levels of the game. After all, he should know.

February 7, 2013

Africa Remix Conference

Well, the snowstorm in Boston will be shortening the length of the conference, and the performance by Debo Band has been cancelled. However, Harvard’s Africa Remix Conference will be on and live tomorrow! (Friday, February 8th)

A lot of interesting folks will be presenting, including a keynote speech by Francis Falceto the owner of the Ethiopiques record label. I am presenting in a panel called Producing Global Sounds, and will be talking about my experiences and practices as a 2nd-generation Sierra Leone diasporan and DJ. If you are conveniently in the Boston area you probably don’t have to go to work, so stop by!

For those of you who don’t want to brave the weather, or don’t live within reasonable distance from Cambridge, Massachusetts, follow the conference on twitter with the hashtag #AfricaRemix starting at 8:30am Boston time. The presentations are being recorded and will eventually be posted on the web, so we will share them with you in some form at a future date.

Photographer Mário Macilau’s Portraits of the “Forgotten” Elderly

On display this month at the Centro Cultural Franco-Moçambicano in Maputo are Mozambican photographer Mário Macilau’s portraits he made of elderly people all over the continent (Nigeria, Congo, Mozambique, Cameroon, Kenya, Mali, etc.) during the year 2012. The title of the series is “Esquecidos” (Forgotten). In a short email, Mário Macilau explained his project:

On display this month at the Centro Cultural Franco-Moçambicano in Maputo are Mozambican photographer Mário Macilau’s portraits he made of elderly people all over the continent (Nigeria, Congo, Mozambique, Cameroon, Kenya, Mali, etc.) during the year 2012. The title of the series is “Esquecidos” (Forgotten). In a short email, Mário Macilau explained his project:

A number of studies indicate that the average life expectancy has increased in the last decades. The implementation of technology, agriculture, medicine and sanitation have contributed to this phenomenon. As a result, this significant part of the population is reaching an age that does not permit this population to participate in labour nor to contribute to the production of everyday activities and self-maintenance. The growth of the population over sixty-five years – the age of retirement – is only increasing to such an extent that the elderly population might constitute half of the entire European population in the coming twenty years. Could ageing thus be understood as a blessing?

In affluent societies, the demands of the high-performance labour that is paired with the increasing life expectancy, a culture of care homes has been put in place. Elderly members of the family are placed in these homes under care of professionals who are often strangers to these vulnerable groups. Care homes are part social club, dispensaries and hospices.

This culture of displacement stands in contrast with social values of the traditions of living together and growing old in one homestead, whereby senior members of the family were cared for by their offspring. Such cultures can still be found in rural areas and some parts of African countries.

* “Esquecidos” runs until 5 March 2013 at the Centro Cultural Franco-Moçambicano.

The Story of a South African Farm

As of March 1 this year, the new base salary for farm workers in South Africa will be R105 a day (about US$11 per day). That’s a 52% pay raise, which sounds impressive until you realize that means currently the base salary is R69 a day (US$7.70 per day). This raise comes after a prolonged, and unprotected, strike by farm workers last year, a strike that put the small Western Cape farming town, De Doorns on the map … again. The raise will lead to many, and perhaps endless, debates on inputs and consequences. Will the pay raise result in job losses? Will the farmers use the rise in minimum salary as an excuse to fire and evict farm workers and farm dwellers? Given farmers’ retaliatory dismissals and evictions after the strike, it looks likely. How will the salary increase affect inequality? What is inequality, exactly?

As of March 1 this year, the new base salary for farm workers in South Africa will be R105 a day (about US$11 per day). That’s a 52% pay raise, which sounds impressive until you realize that means currently the base salary is R69 a day (US$7.70 per day). This raise comes after a prolonged, and unprotected, strike by farm workers last year, a strike that put the small Western Cape farming town, De Doorns on the map … again. The raise will lead to many, and perhaps endless, debates on inputs and consequences. Will the pay raise result in job losses? Will the farmers use the rise in minimum salary as an excuse to fire and evict farm workers and farm dwellers? Given farmers’ retaliatory dismissals and evictions after the strike, it looks likely. How will the salary increase affect inequality? What is inequality, exactly?

Here’s what is clear: the lives of black and coloured farm workers (there are hardly any white farm workers) and their families who live and work on the farms in the bountiful and lush Western Cape of South Africa is impossibly hard. And the hardest hit, every single day and across the span of a life, are women. Women farm workers, women farm dwellers.

Women are paid less than men. Women, sometimes doing exactly the same work as men for exactly the same period of time, are classified, by their employers and by the State, as ‘seasonal’ and ‘temporary’. Women are denied access to positions that might allow for any advancement.

The Western Cape has the highest rates of alcohol abuse accompanied by extraordinary levels of gender-based violence, and trauma, in its farm working communities. The “dop” system of payment (basically paying workers with alcohol) in wine lives on, only in a slightly different guise. What does not change is that at the end of the day, the target of the physical and structural violence is women.

Along with rampant TB, occupational health hazards, such as pesticide, target women as well. Women seldom receive legally mandated protective clothing and equipment. Farm workers live on farms. They often live next to sprayed crops, and so their homes become hot spots for respiratory ailments, skin lesions, and worse. And for the children, of course, it’s worse. All of this then redounds to women’s ‘reproductive labor’ obligations.

Meanwhile, most farm worker households buy their food from company stores, on the farm. Guess what? The prices for food are higher than they are in the cities. In the midst of plenty, food insecurity, hunger, starvation abound, as does a vicious cycle of indebtedness. All of this crystallizes, again, in violence against women.

As Colette Solomon, acting director of Women on Farms, noted, “It’s an immoral perversion that people who are producing food are the ones who don’t have food, and who’s children go to school hungry … It’s invisible hunger and almost normalized.”

The hunger is not invisible. The women farm workers and farm dwellers are not invisible, either. Rather, they aren’t deemed worth commenting on. Women farm workers and farm dwellers appear, more often than not unnamed, in article after article on the farm workers’ strike. They are the specter that haunts the Boland.

The BBC has known for quite a while that life is hard for women farmworkers in the Western Cape. In 2008, it devoted an entire show to South African women farmworkers: “Change is slow — especially for black women who make up the largest number of farm workers on the vineyards.”

A 2011 Human Rights Watch report on the fruit and wine industries of the Western Cape declared that the face of the abused farm worker is a woman’s face. Along with inferior treatment, women workers didn’t receive employment contracts in their own name. Pregnant women were refused employment, and so many hide their pregnancies in order to get a job. For women farm dwellers, it’s worse. They have no rights to housing or anything, which means they have to stay with their partners, in often abusive situations.

And of course, the State gives absolutely no gender specific training to labor inspectors or any other functionaries who might attend to farm workers’ lives. That’s left to the ngo’s, underfunded, understaffed, over-worked, and, at some level, without real power to effect transformative change, much less provide the necessary social services at a mass level.

For women, the conditions of farm labor and farm dwelling are an ever intensifying, ever increasing, ever-expanding toxic stew of vulnerability.

Women farm workers and women farm dwellers know this, and have been organizing. Denia Jansen, a women’s organizer with the Mawubuye Land Rights Movement, has been organizing women farmworkers and women farm dwellers. Women like Sarah Claasen and Wendy Pekeur and thousands of others have worked tirelessly organizing Sikhula Sonke, a women-led trade union social movement that, along with Commercial, Stevedoring, Agricultural and Allied Workers Union (CSAAWU), is the home for most farm workers, and farm dwellers, in the Western Cape.

The story of women farm workers and farm dwellers is not a story of abjection nor of individual heroines engaged in tragic, and implicitly impossible, combat. It’s a story of everyday struggle in which women workers know what’s what and don’t like it, and work to change it for the better. Every day. So when you read the stories of farm workers (and when you don’t read the stories of farm dwellers) and when you read the debates about inequality in the farmlands of South Africa, ask, “Where are the women in this?” They’re there, organizing.

An Interview with South African Jazz Artist Shane Cooper

The best interview subjects often-times turn out to not only possess an affable personality, but also tend to express vast, in-depth knowledge in whatever the topic under discussion may be. Cape Town-based bassist Shane Cooper is one such character. A mainstay in bands like Babu as well as the Kyle Shepherd trio, Shane also doubles as an electronic music producer, cooking up warped left-field beats with the dexterity of a digital marksman under his alter-ego, Card On Spokes. He speaks as excitedly about Charles Mingus’s compositional genius as he does about, say, Sibot’s amazing live show. “Sibot’s set leaves a lot of room for improvisation, which I really admire. He’s seriously playing a lot of those beats live,” Cooper says. Recently, Cooper got awarded the Standard Bank Young Artist Award in the jazz category. The awards, now in their twenty-ninth year running, are not without their critics. We decided to pick Shane’s brain on South African jazz in particular, and the jazz world in general.

The best interview subjects often-times turn out to not only possess an affable personality, but also tend to express vast, in-depth knowledge in whatever the topic under discussion may be. Cape Town-based bassist Shane Cooper is one such character. A mainstay in bands like Babu as well as the Kyle Shepherd trio, Shane also doubles as an electronic music producer, cooking up warped left-field beats with the dexterity of a digital marksman under his alter-ego, Card On Spokes. He speaks as excitedly about Charles Mingus’s compositional genius as he does about, say, Sibot’s amazing live show. “Sibot’s set leaves a lot of room for improvisation, which I really admire. He’s seriously playing a lot of those beats live,” Cooper says. Recently, Cooper got awarded the Standard Bank Young Artist Award in the jazz category. The awards, now in their twenty-ninth year running, are not without their critics. We decided to pick Shane’s brain on South African jazz in particular, and the jazz world in general.

Who is the one bassist you look up to in jazz?

There’s a whole bunch of different things. Mingus is a huge influence, especially compositionally. Pattitucci, Ray Brown for some old school stuff and Ron Carter as well for the real traditional playing, and then the way Ron Carter took it to new things with Miles. There’s a whole host of guys. I guess I look to different cats for different things, so there’s some guys I’ll look to just for the way they play the blues, and I’ll look to another guy for the way they play more odd time signature stuff. Look at Derrick Hodge who plays with Robert Glasper, and the way he plays hip-hop, but hip-hop in a jazz band … he’s bad-ass, his sound and choice of notes and stuff. It’s amazing, he hits the nail on the head! It’s the same kind of thing I get from Pino Palladino who played on D’angelo’s “Voodoo” album; it’s just the perfect placement of notes for hip-hop stuff. And just jazz guys in general, a whole bunch of different composers and new guys that I like. A lot of the inspiration for the new guys comes from the old guys as well.

You’re from Port Elizabeth, which is in the Eastern Cape. The Eastern Cape has a whole lineage of amazing jazz cats. Were you familiar with the scene when you were coming up?

Yes, I was. There were a lot of guys that I discovered only later they originally come from PE and the Eastern Cape at large. But when I was coming up I was playing with a guy named Gerard O’Brien who’s originally from The Genuines, an old Ghoema punk band from the eighties (with Hilton Schilder and Mac McKenzie). I played with him and this guy named Graham Beyer when I was sixteen, in bars and clubs around PE. I really cut my teeth with those guys, that’s when I started learning a lot more about how to really play in a jazz group. We connected with guys; there was a small scene there but there were a lot of guys who were passionate about it. But many of the jazz musicians have moved to other cities. It was a cool place to grow up, but creatively there’s a very limited bunch of venues you can play at.

So why did you move to Cape Town?

Well I wanted to study jazz, and I was looking at different universities. The Cape Town one (SACM) looked like a good option. And then I had a couple of mates here that I’d met that said I should come by and we can work on some stuff. It kinda seemed like the obvious choice, and I’d always really liked the whole scene here, everything that I’d heard coming out of Cape Town in jazz, electronic music and everything was cool. So I was pretty easily swayed.

How does the relationship between musicians work in the collaborative projects that you have been involved in, like Babu and the Kyle Shepherd trio for instance?

Kyle’s group is a good example of something where Kyle is the composer and the leader and the vision of the group, it’s his whole concept. And he came and basically contacted Jonno (Sweetman, drums) and myself. I can’t remember exactly when we started playing together. When someone invites you to come and play their music, it’s not a definite that anything’s gonna happen. It might just sound okay, and then you do one or two shows and it kinda ends there. The first couple of shows are really the test to see if there’s chemistry. We played, and I feel like we had a definite chemistry from the get-go, and it developed into a really good working relationship over several years, and Jonno and I have a really good core connection as bass and drums, which is really important. You can have a good bass player and a good drummer who don’t connect, and then the whole thing falls apart. Jonno and I really work well together; I think Kyle felt that from the beginning, that this thing is working and we had a connection. That’s really the main thing, and then the rest is all the work that Kyle has put into the project, and bringing us into his space, then us rehearsing and working on the stuff. But fortunately we had a natural musical connection from the beginning. And then a lot to it is also, I think, liking similar things and different things. There’s a lot of stuff that we listen to together to get inspiration; when we’re on the road together we’ll watch DVDs, stuff of bands that we dig. At the same time there’s stuff that I listen to that the other guys don’t like, and vice versa. But that also informs my playing and brings out something that they can connect with vicariously.

How are the experiences while on tour?

How are the experiences while on tour?

It’s cool. One of my favourite parts of playing music is getting to travel. You experience the different scenes; every place has a different way of working. So you see how the audiences listen to music, the way the venue’s run, and even the way things work behind the scenes — the way the engineers operate. It’s just really cool to experience it because the music scene at large is all connected, but at the same time it works so differently in every place. I love it! If you connect with the audience anywhere in the world, it’s a great thing. Meeting musicians elsewhere is really cool, you realise that the world is kind of small. The cool thing in the jazz world is that it’s not as affected by the ‘celebrity thing’ as it is in a lot of other genres. You can meet big names — I mean, some of them are untouchable — but you can meet big names and they’re often very cool. You just hang with them and chat about whatever, it’s not such a mission. It’s amazing to be on a train in some other country and you look out and you’re like ‘oh my god, I’m here for music!’

How has a place like The Mahogany Room helped you out as a musician living and working in Cape Town?

Well, it’s the only dedicated jazz venue in Cape Town, the Monday night jazz jam is just on Mondays. Tagore’s is also the other one, but they both cater for a different kind of feeling — the Mahogany is a sitting concert venue and Tagore’s is more of a bar space where people talk and chat during a gig. I like both for different reasons, but there’s a lot of music that needs to be performed in a listening space because you need to be able to hear everything that’s going on. It’s imperative for the future of music to have a venue like Mahogany Room so that artists have a place to play their stuff, or they would really struggle. Before the Mahogany Room, you could maybe hire out a space, but if you had a band with a piano in, it’s very hard to find a spot with a piano, and hiring something big like a place at the Baxter or Artscape is beyond any of our budgets, so you have to look at universities and schools. But that’s also difficult because those places don’t have traffic for concerts all the time; you have to market really hard, and it’s difficult. So the Mahogany Room, ja, it’s a go-to place, people know that they’re gonna go and get a concert. It’s also important that a lot of new people … there are a lot of young people who don’t necessarily go to concerts like that because they haven’t been exposed to it. I love going to see a gig where I can just sit and be quiet and listen to the entire show. And then I also like going to a bar where it’s a pumping vibe and people are dancing, singing along and going crazy. They’re both really important for the scene. For a while it was just the one side. It’s something that a small, up-and-coming jazz band can actually do without having to worry about hiring a theatre with lighting engineers and sound engineers. And it’s small and intimate as well; if you’re sitting right at the back of the room you can hear what’s going on. I certainly think it’s an encouragement to people because they now know that they’ve got a space like that, so they’re like ‘okay, well, if I write something that is fitting for a room like that, I should do it.’ So there’s been a big step in the right direction.

And how is working with Babu?

That’s been great! I don’t know if you’ve heard though, we broke up last week.

Didn’t you guys just play two shows recently?

Yeah, we played two shows and we split up after the second show. It’s a sad thing because we’ve been together for seven years, but it’s the end of that long journey.

But will you still be working with the rest of the other band members on other projects?

Yeah, Kesivan — I play in his group (The Lights); and I play in Reza’s group, his quartet stuff. We’ll still all work together, but just Babu itself has disbanded. There’s no hard feelings. We’re all still really good friends, there’s no weird vibe or anything like that.

So you got awarded the Standard Band Young Artist Award for 2013 in the jazz category. Where were you when you received the news?

I was in studio working on some mixes, and they called me up. It was a big surprise, I didn’t expect it. It was pretty weird as well because I was in the studio and they were like “don’t tell anyone yet until it’s announced,” so I had to be quiet. I was really stunned by it, I didn’t expect that call at all! It was a huge honour to get it.

Has it changed anything? For instance, are you getting more bookings than previously?

What it really comes down to is that they’ve given me some shows at the Grahamstown Festival. I’ve been writing music for several years, jazz music that I’ve performed in different groups, and I’ve been waiting to put together my own group under my own name. But I’ve never got to it yet because I’ve been really focused on the collaborations that I’ve been in, stuff like Babu. I was in this band Restless Natives for several years, Closet Snare and stuff. So a lot of my writing energy and efforts in the jazz world were focused on those collaborations. It was always something at the back of my mind: okay, soon I’m gonna put together my own group. And then they gave me that award and were like “we’ve got some shows for you in Grahamstown.” So we’re recording a record at the end of April, it’s got Kesivan (Naidoo, drums), Reza (Khota, guitar), Bokani Dyer on piano, and Justin Bellairs on alto saxophone. And then I’m gonna do two collaborative shows at Grahamstown with some international guys (from Europe) as well. So that’s the main thing, they give you a showcase there. It will amount to some more shows that come up over the year with my band hopefully.

Don’t you feel that the award might turn into a curse at some point? That it will stunt your growth in some way?

So far I haven’t found that. There’s been no restriction put on me creatively whatsoever, there are no clashes with me asking to be able to do something with my group that they’ve gone “it doesn’t fit the profile.” There’s nothing like that. I’ve had complete creative freedom, so I haven’t experienced that. I honestly think there should be more corporates doing stuff like this for the jazz world. There are millions spent on sport, and I understand that they get way more advertising time from it, but there should be way more companies investing in jazz in this country. Because it’s a big thing, there are a lot of kids that are into jazz in school, you know?! It’s not a side-line thing. I know that thousands of kids around the country are really into jazz, I see them at Grahamstown every year and all around the country when I go to play places. If there were more corporates investing in jazz, I think it would just help the scene a lot more. There’s the FMR competition which is a good thing as well, and the SAMRO Contest, and those are two really good initiatives. But we need way more. Not just jazz, other stuff as well; arts in general. There should be more tax incentives for this sort of thing as well, for companies to invest in the arts.

Kyle Shepherd mentioned in an interview that part of the reason he dropped out of university was that he felt they were not teaching him what he needed to know. Do you feel that there’s an awareness, at least now with the cats that are coming up, of South African jazz?

I think there is, I think there’s been an increase, definitely in the last few years. While I was there (in university), there were a few cats; there was a guy named Mongezi (piano player), M’du (piano player), Bokani and Kyle, they were all checking out that stuff, checking out Bheki, checking out Moses. But there’s been a definite increase and even more guys, it’s been really cool to see. I’ve heard that they’re trying to make a better South African jazz course, but while I was there, they spent almost no time on it, which was sad. There was no love given to that part of it. Because the artists who’ve come from this country have really done very unique things in the jazz world. It should be more important to us.

* Images by Jonx Pillemer.

February 6, 2013

Super Eagles!

Nigeria’s Super Eagles have in the last few minutes brushed aside the Eagles of Mali to move imperiously into the final match of the 2013 African Cup of Nations. First half goals from Elderson Echiejile, Brown Ideye and current leading scorer, Emmanuel Emenike ensured that a 1-1 scoreline in the second half was simply academic.

The match began with both sides playing a little cautiously, and the Malians playing a 4-1-3-1-1, sitting back and looking to catch the Nigerians on the break or on set pieces.

A few shots aside, the game finally came to life on 27 minutes when the brilliant Victor Moses, sprinting down the right flank, turned Adama Tamboura inside-out, nutmegged him for good measure, before squaring a waste-high ball to the far post which Elderson Echiejile ducked to nod past the helpless Mamadou Samassa in the Mali goal.

A few minutes later, Nigeria doubled their lead, Emenike the provider. Once again down the right flank, he took a pass from Victor Moses, skinned his man, drilled a hard, low ball towards the near post, where Brown Ideye slid in alongside a defender to bundle it past Samassa.

Ten minutes later, the game was over as a contest. Emmanuel Emenike took a free-kick which deflected off Mohammed Sissoko and hopelessly wrongfooted Samassa.

Though there were two goals in the second half, one for Nigeria by substitute Ahmed Musa, and Mali substitute, Cheick Diabate, the Super Eagles held on for Sunday’s final where they will play either Burkina Faso or Ghana.

When the referee blowed the final whistle, Super Eagles coach Stephen Keshi embraced defeated Mali great Seydou Keita & several of his former players.

Peter Beinart went to South Africa and concludes government is sympathetic to Palestinians because South Africa has more Muslims than Jews

By Melissa Levin

The next time Peter Beinart, who wrote a post on “The Israel Debate in South Africa” for The Daily Beast, visits South Africa, he ought to spend more time, with more people, getting a deeper sense of the complexities of the country and its struggle history. He may learn then, for starters, that South Africa is not America on steroids. America is America on steroids. And he’ll also learn that the affinity of the masses of people to the Palestinian struggle is hardly as mysterious and convoluted as he would suggest. These two points are connected. Beinart shouldn’t confuse American racism with the Apartheid state. The fight against racism in the United States was registered in a vocabulary of civil rights. For South Africa, the battle was for the fundamental transformation of a state that was colonial to its core. The language of liberation directed the struggle there. It was not about the extension of South African citizenship to include the majority; but it was to be a fundamental reordering of what it means to be South African. Until 1994, the South African state operated in the interests of whiteness. And Jews, in the main, unquestioningly embraced their whiteness. Contrary to the idea posited by Beinart about the sense of national belonging of Jews to South Africa, he should know that we sang the national anthem (on multiple occasions, including at day schools), we supported the whites only rugby and cricket teams, we participated in whites only elections, in white political parties, in prosecuting apartheid laws, in doing apartheid business.

But this is not why the post-apartheid polity supports the liberation of Palestine.

Because of course, as Beinart points out, there were many Jews who disavowed apartheid and risked everything in the fight against it. He is mistaken though that those same Jews disavowed their Jewishness in favour of a broader identity. He should know that it is possible to be Jewish and not be a Zionist. In other words, the support for Palestinian statehood is not about identity politics. Rather, it is ideological; it’s about ideas of freedom and justice.

If Beinart spent more time with more people in South Africa, he would know too that the support for Palestinian liberation is not produced through a more assertive Muslim current in the ruling party than a Jewish one. The role and place of Muslims in the ANC and support for the organization amongst Muslims is not so unequivocally established. Support for Palestinians is not support for Muslims over Jews in the ruling party. It is support for an occupied people over a repressive state.

Beinart correctly identifies Israel’s collusion with the apartheid state as grounds for some animosity in the post-apartheid polity. But he doesn’t concede the full implication of it. Beinart claims that “apartheid turned many of the South Africans who were struggling to forge an inclusive, non-racial South African identity against the Jewish state” (my emphasis). But it was the apartheid devil that did it – it was the choice of the Israeli state to work with apartheid, to work with counter-revolutionary forces against the liberation of South Africa that solidified its place as pariah. And, frankly, ethnic and religious nationalism gives itself a bad name, wherever it asserts itself.

Peter Beinart went to South Africa to find out why the government supports the struggle of Palestinians over Israel

By Melissa Levin

The next time Peter Beinart, who wrote a post on “The Israel Debate in South Africa” for The Daily Beast, visits South Africa, he ought to spend more time, with more people, getting a deeper sense of the complexities of the country and its struggle history. He may learn then, for starters, that South Africa is not America on steroids. America is America on steroids. And he’ll also learn that the affinity of the masses of people to the Palestinian struggle is hardly as mysterious and convoluted as he would suggest. These two points are connected. Beinart shouldn’t confuse American racism with the Apartheid state. The fight against racism in the United States was registered in a vocabulary of civil rights. For South Africa, the battle was for the fundamental transformation of a state that was colonial to its core. The language of liberation directed the struggle there. It was not about the extension of South African citizenship to include the majority; but it was to be a fundamental reordering of what it means to be South African. Until 1994, the South African state operated in the interests of whiteness. And Jews, in the main, unquestioningly embraced their whiteness. Contrary to the idea posited by Beinart about the sense of national belonging of Jews to South Africa, he should know that we sang the national anthem (on multiple occasions, including at day schools), we supported the whites only rugby and cricket teams, we participated in whites only elections, in white political parties, in prosecuting apartheid laws, in doing apartheid business.

But this is not why the post-apartheid polity supports the liberation of Palestine.

Because of course, as Beinart points out, there were many Jews who disavowed apartheid and risked everything in the fight against it. He is mistaken though that those same Jews disavowed their Jewishness in favour of a broader identity. He should know that it is possible to be Jewish and not be a Zionist. In other words, the support for Palestinian statehood is not about identity politics. Rather, it is ideological; it’s about ideas of freedom and justice.

If Beinart spent more time with more people in South Africa, he would know too that the support for Palestinian liberation is not produced through a more assertive Muslim current in the ruling party than a Jewish one. The role and place of Muslims in the ANC and support for the organization amongst Muslims is not so unequivocally established. Support for Palestinians is not support for Muslims over Jews in the ruling party. It is support for an occupied people over a repressive state.

Beinart correctly identifies Israel’s collusion with the apartheid state as grounds for some animosity in the post-apartheid polity. But he doesn’t concede the full implication of it. Beinart claims that “… apartheid turned many of the South Africans who were struggling to forge an inclusive, non-racial South African identity against the Jewish state” (my emphasis). But it was the apartheid devil that did it – it was the choice of the Israeli state to work with apartheid, to work with counter-revolutionary forces against the liberation of South Africa that solidified its place as pariah. And, frankly, ethnic and religious nationalism gives itself a bad name, wherever it asserts itself.

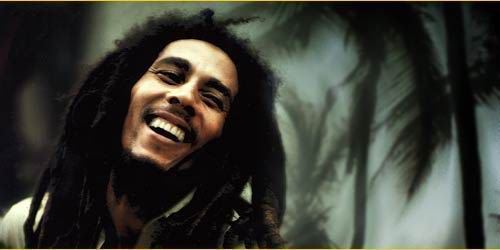

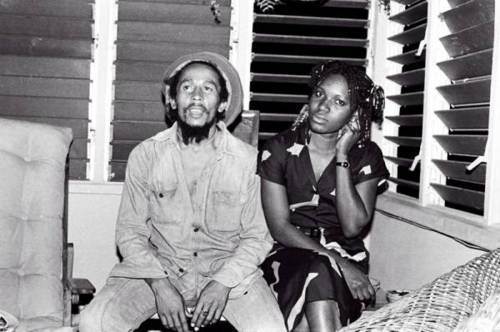

When Bob Marley went to Africa

The public persona (and the politics) of Bob Marley, whose birthday it is today,* was heavily informed by his relationship with Africa (both symbolically and in a real sense). A good place to see that play out was in director Kevin MacDonald’s critically acclaimed film, “Marley,” where McDonald plays up that connection to full effect. (I watched the film again for the umpteeth time recently.)

The public persona (and the politics) of Bob Marley, whose birthday it is today,* was heavily informed by his relationship with Africa (both symbolically and in a real sense). A good place to see that play out was in director Kevin MacDonald’s critically acclaimed film, “Marley,” where McDonald plays up that connection to full effect. (I watched the film again for the umpteeth time recently.)

Here’s the trailer again:

The film opens on the Ghanaian coast at the remnants of a slave post, the camera then pans over the Atlantic, finally settling on the green hills of rural Jamaica (Marley’s birthplace Nine Mile) from where it picks up Bob Marley’s story, thus cementing a link between the continent and its new world diaspora. In his youth, Bob Marley was drawn to the teachings of Leonard Howell, who organized Rastafarians on the island since the 1930s. Mortimer Planno, Marley’s dummer, played a big role in this. Rastafari drew on Jamaican Marcus Garvey’s advocacy of the repatriation of Jamaicans (and all people of African descent) back to Africa. Rastafari also revered the Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie (who had resisted Italian occupation) as a living deity. In April 1966, Selassie visited Jamaica and ecstatic crowds awaited him at the airport, as the film shows. Bob Marley himself would later record “Selassie Is the Chapel” (his version of the Elvis Presley hit “Crying in the Chapel”), as a homage to Selassie.

Bob Marley, like many other Rastas, also shared a desire to visit the African continent and of course, later on–when he could afford to or was invited–he travel there. Strangely, the first place McDonald suggests he visited was Gabon in January 1980. Then later in 1980 he played at independence celebrations of Zimbabwe from British colonial and white minority rule. MacDonald’s film covers both these trips in some detail. Oddly, MacDonald’s film is silent on his earlier visits to Kenya and Ethiopia in 1978. Nevertheless, the trips MacDonald covers point to some of the contradictory impulses of Marley’s politics.

When Marley went to Gabon, the country was a dictatorship. The regime of President Omar Bongo (he had been in power since 1967; by the time of his death in 2009, he had ruled, uninterrupted for 41 years) was built on oil wealth and was notorious for its corruption and repression of political opponents. Successive French presidents, through Françafrique, propped up Bongo’s rule in their former colony since Bongo did not interfere in the business of French multinationals who dominated the economy and funded election campaigns back in France.

Marley, it seems, had fallen for Pascaline Bongo, the dictator’s daughter. They were dating at the time (though not exclusively as Bob often carried on a number of concurrent relationships). In the film, Pascaline paints Marley as some kind of black consciousness figure. When they first met, Marley scolded her for having her hair processed (he called her “ugly”). Marley then agreed to play a birthday show for her dad. MacDonald’s interlocutors suggests that Marley did not know Bongo was a dictator (for real) and only figured this out once he gets there, but still decided to play anyway since he had traveled this far. (The film, interestingly, spends more time on a sequence of events where Marley and some members of his band confine and interrogate their manager in his hotel room after accusing him of stealing from the band.)

In an interview with with LargeUp last year, MacDonald tried to say more about the Gabon trip:

In an interview with with LargeUp last year, MacDonald tried to say more about the Gabon trip:

I had been told by a few people that [Pascaline Bongo] had been very important in the last years of his life, in introducing him to Africa. The first time he played in Africa he was invited by her father but her, really. That seemed like a key point in his life. Obviously Africa means so much to him. I thought here’s a bizarre story, a strange individual in this incredibly luxurious environment and you feel like that’s a million miles from Trenchtown, so that appealed to me. They’d had a relationship that went beyond just a girlfriend relationship, I think she’d been also instrumental in a couple things in his life. She visited him in Germany before he died.

(BTW, Pascaline Bongo is still around in politics in Gabon. Her brother is President now. The government is still the family business. And musicians and pop stars still go there insisting it is not a one-party state and they still pose for pictures with Pascaline Bongo. Like Michael Jackson and later Jay Z.)

The film then turns to Marley’s decision to pay to fly his band at a cost of US$90,000 to celebrate Zimbabwe’s new independence. Marley even specially composed a song for Zimbabwe’s freedom (he had been performing it for a while). Here’s video footage mashing together crowds scenes, performing the song, “Zimbabwe,” in the famed Rufaro Stadium:

MacDonald’s film confirms the story that Marley foresaw the Zimbabwean government’s political excesses and especially the fate of Mugabe. In “Zimbabwe” Marley sang: “Soon we’ll find out who is the real revolutionary.” Also, earlier during the concert, as overzealous riot police teargassed crowds trying to get into a full stadium, Marley refused to leave, braving the teargas with his fans, it seems.

There’s more evidence of Marley’s attitude towards Mugabe and vice versa. Too bad the film doesn’t spend any time on the story that Mugabe preferred Cliff Richard, the clean-cut British singer, to perform at the celebrations. And last year, around the time the film first hit theaters worldwide, Mugabe in an interview with a Zimbabwean radio station insulted Jamaican men, including Rastafari, for being “as drunkards who are perennially high on marijuana.”

The main takeaway from MacDonald’s film is that Marley was politically naive or got bad advice. I can see Marley’s fans and confidantes disagreeing with such an interpretation. But MacDonald’s film also argues that in the 1970s Marley was naive about Jamaican garrison politics (essentially an arrangement between politicians and local gang leaders to guarantee voting blocs). In fact, the main reason for Marley leaving the island in the 1970s was after a politically motivated assassination attempt at his house where he was shot.

As I mentioned before, one trip that Marley took to an African nation that is strangely not mentioned in MacDonald’s film is Marley’s 1978 visit to Kenya and Ethiopia. This is especially odd given the connection between Rastafari and Ethiopia. As BobMarley.com reports:

During his Ethiopian sojourn, Bob stayed in Shashamane, a communal settlement situated on 500-acres of land donated by … Haile Selassie I to Rastafarians that choose to repatriate to Ethiopia. Marley also traveled to the Ethiopian capitol Addis Ababa where he visited several sites significant to (Selassie’s) life and ancient Ethiopian history.

I may be missing something, but I have not seen anything online where MacDonald explains this omission.

* BTW, In one of those weird coincidences, today is also the birthdays of Ronald Reagan and Kris Humphries.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers