Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 437

December 5, 2013

Songs for Mandela [International Edition]

When we sent around the AIAC “office” inviting our contributors to suggest songs for Nelson Mandela (both music about him and tracks that could stand as tributes to the man), the suggestions came flooding in. This is the international edition of our Songs for Mandela. It’s a bumper playlist, and in no particular order. Enjoy and feel free to post your own favourites in the comments. Steffan will take us through a blockbuster selection of the many tracks for Mandela by South African artists tomorrow.

We’ll start with Miles Davis, “Amandla”, from his 1989 album of the same name (the whole thing’s here).

Next up it’s Burning Spear, and “Mandela Marcus”.

Jamaican dancehall giant Shabba Ranks, “Mandela Free” (and here’s some footage of when Shabba came to give Madiba a hand on the campaign trail):

Gil Scott-Heron. “Johannesburg”. Enjoy.

From Haiti, this is Dieudonné Larose with a live version of the hit song, “Mandela”:

Here’s Senegalese rapper Didier Awadi with a cracker from his album “Presidents d’Afrique” — “Amandla (Mandela)”. Awadi did a great job splicing in lines from Mandela’s inauguration speech. All rise.

From his 1995 album, “Folon”, this is the great Salif Keita, “Mandela”. On the same album, he sung the praises of Sékou Touré. Keita’s international career took off following his appearance alongside the likes of Youssou N’dour, Miriam Makeba and Hugh Masekela at the massive concert that was held at Wembley for Mandela’s 70th birthday (some clips here – for some reason only of British and American performers).

This is the title track from Youssou N’Dour’s 1986 album, “Nelson Mandela”:

Probably the most famous song campaigning for Mandela’s release, and one of the best-known anti-apartheid tracks around the world, was by a group from … Coventry, England. The Specials got a big hit with “Free Nelson Mandela”.

Let’s hear that again, this time with the much-missed Amy Winehouse on lead vocals. Her rendition closed the concert celebrating Mandela’s 90th birthday in Hyde Park.

Ivorian reggae artist Alpha Blondy tells it like it is. “Apartheid is Nazism”.

We couldn’t not have something from Linton Kwesi Johnson. First up, here’s “Mi Revalueshanary Fren”…

…and secondly “Wat About Di Workin Class”?

Here’s Zambian rapper Zubz with “My Distress”:

“Mandela, cell dweller, Thatcher / You can tell her clear the way for the prophets of rage / (Power of the people you say).” Yes, it’s Public Enemy with “Prophets of Rage”.

From Reggie Rockstone, it’s “Keep Your Eyes on the Road”

Who knew Arsenio Hall could sound so earnest? It’s because he’s introducing Maze and Frankie Beverley with “Mandela”.

The Klezmatics and Chava Alberstein with “Di Goldene Pave” (The Golden Peacock):

We’ll leave the last word to Bob. Rest in peace, Madiba.

*With thanks to Johan Palme, Jimmy Kainja, Gregory Mann, Amílcar Tavares, Serginho Roosblad, Melissa Levin, Siddhartha Mitter, Marissa Moorman, Ngoan’a Nts’oana, Jesse Shipley, Cheta Nwanze, William Glasspiegel, Jonathan Faull, Nick Barber, Zachary Rosen, Jacques Enaudeau, Dylan Valley, Tom Devriendt, Steffan Horowitz and Sean Jacobs for their suggestions on these playlists.*

10 excuses most Dutch people make for racism

Today is the day Sinterklaas and his little black slaves give candy to children, although nature got in the way somewhat. As you’re aware, “Zwarte Piet” (translated: Black Pete) is how the helpers of Saint Nicholas are known — he is white and they come complete with golliwog-style wig, pronounced red lips, speak with funny accents. Dutch authorities felt Zwarte Piet can’t be racist anymore because they removed his gold earring. This year, the Dutch can’t hide how racist this “tradition” is anymore. Everyone from the New York Times, BBC to CNN has covered it. We’ve had a few spats on Twitter, Facebook and on the blog with people (mostly Dutch, it seems) who still think blackface is clean fun. Anyway, we compiled a list of the 10 excuses most Dutch people make for racism:

1. Slavery was such a long time ago; slavery has nothing to do with Zwarte Piet. It’s just those who like to be victims who still complain about slavery. The Dutch only had a small percentage of slaves either way. Rather let’s just talk about the glorious VOC period and how the Dutch pioneered in trade.

2. The Dutch don’t even see color; everybody is equal here and blacks and whites are totally treated equally. Why else would they want to live here, right? Discrimination on the labor market? That happens to everyone, also to blonde people, you know.

3. All children like Zwarte Piet; you can’t take Zwarte Piet away from the kids, it’s all for the kids, the kids will not understand, they love it. Racist images are of course not normalised and accepted.

4. My black neighbors’ daughter likes Zwarte Piet; see even black people dress up as Zwarte Piet. Are they racist too? And people on Curacao also celebrate Zwarte Piet and they love it. If they do it then there must not be anything wrong with it, right?

5. Zwarte Piet is not Blackface; blackface is only in the USA, here it’s just different. Zwarte Piet came through a chimney and that made him black. There’s of course plenty of neutral and non-biased research done on that. And his afro wig, red lips and golden earrings are just funny. Nothing to do with stereotypes.

6. If Zwarte Piet is racist white bread is too; everything is reverse racism. You talk about the ‘Dutch being racist’? That’s racist! You want to take away Zwarte Piet from us? That’s racist! You need to respect the Dutch culture or go home. That’s not racist.

7. Opponents of Zwarte Piet are extremist; opponents must at all times refrain from trying to say anything about the national blackface hero in relation to racism. If you speak up in the public domain on Dutch institutional racism and white hegemony you are an extremist by default.

8. By opposing Zwarte Piet you are actually creating racism; we never had racism but now that these extremists and other folks kept talking about it, well yes, now you have created a divide that didn’t exist before. Racism is just magic.

9. Americans just criticize Zwarte Piet because they are so PC; it’s only folks in the USA and all the other countries that don’t understand Zwarte Piet. How do they dare criticize Dutch culture?! Let them look at themselves first. They don’t understand our Zwarte Piet and us.

10. It’s never our intention to be racist; if you think Zwarte Piet is racist, which he is not, you must understand that if the intention is not racist it can never be racist. You shouldn’t be using the word racism so lightly either way. Just don’t be offended so easily. We make fun of Dutch people, Chinese people, farmers, Negroes, everyone! That’s just Dutch culture — not racism.

The Book of North African Literature: Pierre Joris on Poetry and Miscegenation

A 743-page anthology of North African literature was published by the University of California last year. Ranging from documents made in sixth century Carthage to experimental prose published months after the 2011 uprisings, the Book of North African Literature is the fourth installment in the Poems for the Millenium, a series initiated in 1995 by Pierre Joris and Jerome Rothenberg with their huge Volume One: from Fin-de-Siècle to Negritude. This latest volume was edited by Joris and Habib Tengour, both poets, scholars and translators; it includes their translations from French and Arabic (alongside many other translators) and commentaries situating each text within the shifting centuries and centres of its experimental format. The Book reflects these poets’ life-work, writing and translating poetry which asks critical questions of identity and cartography; the attempt, here, to grasp the extent of this literature’s influence in Europe, the Middle East and Africa, undermines the cultural borders of this region. We spoke to Joris about the anthology, translating (or not-translating) North African literature before and after 2011.

A note on the text: the Book is emphatically not a linear or genealogical account of the literature of the region; it offers, instead, an account of the multiple beginnings, traditions and genealogies which emerge and reemerge in the literatures of the many languages of the region, and the region’s diasporas. In the first section, ‘A Book of Multiple Beginnings’ in which the first work presented is a prehistoric rock painting from the Tassili region of the southern Sahara (see the above photo, by Patrick Gruban).

The Book proceeds with a series of five sections called diwan (“a gathering, a collection or anthology”) which organise texts chronologically, and divide them between historical moments (‘A Book of Inbetweens: Al-Andalus, Sicily, the Maghreb’; ‘Al Adab: The Invention of Prose’; ‘The Long Sleep and the Slow Awakening’; ‘Resistance and Road to Independence; ‘”Make it New”: The Invention of Independence’). Interspersed between these are sections organised according to various other logics (‘The Oral Tradition’; ‘A Book of Mystics’; ‘A Book of Writing’; ‘A Book of Exiles’).

The last entry is Omar Berrada’s Subtle Bonds of the Encounter, a bilingual poetic essay which samples texts by Alfred Jarry, bpNichol and Ibn Arabi, it is a fitting conclusion to the Book. Written in September 2011, it concludes “Fusion without confusion is only show of science.” The Book of North African Literature makes its most compelling arguments in its refusal to accept totalising representations or impose pseudo-scientific categories on its texts; instead, it witnesses poetry’s tendency to move across borders, creating speculative relations between diverse literatures.

The Book includes a series of origin myths, and presents a multiple relations between poet and language and land. Could you tell us about your friendship and collaboration with Habib, where and when you conceived the idea of the anthology?

Joris: Habib and I met in 1976 at the University of Constantine where I was teaching in the English Department and he in the Department of Sociology. We became friends when we discovered that we were both poets and had very similar interests. We stayed in touch over the years and would meet from time to time in Paris, where Habib moved in the 80s, when I’d come through that town.

I’d thought up the idea of the anthology even earlier — an ur-sense of the need for such a book came to me in 1966 when I met the Moroccan poet Mohamed Khaïr-Eddine in Paris and he introduced me to Maghrebi literature, insisting that it was in the Maghreb that the most interesting and revolutionary literature was happening. That’s when I began to read widely in that literature (as well as in Caribbean francophone literature, as both of these felt richer and wilder and more alive than French “metropolitan” poetry).

Then, in the 80s when Jerome Rothenberg and I imagined and developed the concept of the Poems for the Millennium anthologies, I immediately thought that this concept could be expanded and that I could finally put together this volume on the Maghreb. It seemed useful, in fact, necessary to bring in another person to collaborate on the project, and Habib was a natural, as one of the most accomplished and experimental poets of the Maghreb and as an excellent scholar in the various areas of Maghrebi cultures (as a trained anthropologist, he is, for example a specialist of oral literatures). A year and a half later we handed in the manuscript.

Anthology, from the Greek, refers to a collection of flowers; flowers which are, presumably, cut, dead. I wonder if placing poems in an anthology must involve cutting them off from their roots, preserving them in a lifeless state. Translation redoubles this danger, removing the text from its source-language. So it seems that an anthology in translation poses a number of dangers to the life of a poem. Do the anthology form and the translation form preserve or alter the life of the poems in different ways? Is there a kind of death involved in this process?

The cut flower etymology is a bit of a dead metaphor. Any poem in any magazine or book could be considered a cut flower — i.e. where is the natural, organic garden habitat of the poem? The handwritten notebook, the hard disk on which it is preserved, the live reading? A poem is not a product of nature, it is an artifact. And that applies not only to written and printed, i.e. Gutenbergian artifacts, but also to the oral tradition—Technicians of the Sacred is what Jerome Rothenberg has called the poets in that tradition and they too create artifacts, word-constructs shaped with artificial techniques. Both of us think of the anthologies we have created — alone, together or with others — as “grand collages” to use Robert Duncan’s lovely phrase. They are, like any poem, a multi-layered construct. This does not mean that a poem does not change when its environment changes. A given poem in an anthology will be ever so slightly changed, inflected by the poems by other poets that surround it, than it is in its other “unnatural habitats” — but it is exactly this event, the fact that a new environment enriches a given poem, possibly reveals layers or shadings that had gone unperceived, that to me is proof of the continuing and expanding “life” (if we have to use that organic metaphor) of the poem. And it is exactly at that level that our anthologies want to be different from the traditional, dead, pressed, preserved flower-anthology which are meant as morgues.

Readers of your anthology might be disappointed — surprised, more likely — that so much of its contents exceeds the borders of modern-day North Africa, towards Provence, Andalusia, Sicily, Iraq and Syria. If the anthology is a kind of nomadic institution, why devote it to a region rather than a specific language or dialect?

Like all live and lively cultures, maybe even more so, the culture of North Africa shows a diastole / systole, contraction / expansion rhythm over time. And so yes, there was a moment when the cultural area of the Maghreb included Spain, or at least Andalusia. That culture, usually referred to as al-Andalus, had its origins in the Middle East, but then formed and found its center in Spain, with its cultural goods, especially poetry becoming influential beyond the strict geographical borders of al-Andalus, and, so I argue, constituting the base from which troubadour poetry in Provence and beyond developed. Twice the North African Berbers were called to the rescue by their co-religionary brethren in Spain, and when al-Andalus finally was destroyed by the Spanish, many of its Muslim and Jewish citizens found refuge in the Maghreb. In Sicily it was the European court that thought so highly of the Al-Andalus /Arab culture that it invited people from there into its government and adopted its cultural mores. A great Murcia-born poet and Sufi teacher like Ibn Arabi would spend time in Fez (I was recently shown the little mosque, still standing, very lop-sided, propped up by wooden boulders, waiting for UNESCO money for overdue repairs where he worshipped in the Medina), go to Tunis, move on to Mecca (remember that the hadj is one of the duties of all good Muslims) and wind up living and dying in Damascus. What interests me a lot is the nomadic openness of this culture — just compare the travels and travel diaries of Ibn Battuta to those of his European equivalents, say Marco Polo, and you’ll see the difference in openness.

What interests me too is the diastole/systole of the region over time, complexified by the languages that nomadically come and go, au gré du conquérant over those two millennia and more. Had we had 300 more pages we would have investigated the southern borders of the regions in more detail, i.e. Tschad, Niger, Mali — Timbuktu alone could be a fat chapter or rather diwan — to look at the border complexities where the saharan cultures meet the African ones. We got a little sample of that into the Mauritania and Western Sahara sections. So it is not the definition of a region by drawing borders, limits, but rather the expansiveness, or at least porousness of a border that interest me — what crosses over and mixes is more interesting than what tries to stay stubbornly “pure” or exclusive. As I’ve said elsewhere and keep repeating, miscegenation is the only way to advance, to make it new.

Pierre Joris (left) and Habib Tengour. Photo by Dan Wilcox.

In the section, ‘The Invention of Prose’ you quote a description of Africa by Al-Hasan’ Ibn Muhammad al Wazzan al-Fasi (a.k.a Leo Africanus): “In the Arabian tongue, Africa is called Ifrikiya, from the word Faraka, which in the language of that country means to divide.” The anthology is split up into five sections named diwan and seven chapters, some of them divided by country or region, some by individual author. Is the work of the anthology to make both division and connection between cultures?

Yes indeed, that is part of an anthology’s work. To make the distinctions that will allow the connections to stand out the more clearly. I’ve always considered anthologies as networks that, while highlighting differences, create connections — be they between genres, authors, geographical or cultural realms — that will create a textum, i.e. a weave — in this case, permit me to orientalize a bit, a carpet, a flying one hopefully… I am not interested in the anthology as the alphabetically (or otherwise) arranged list of the cultural hit-parade, like “ the hundred best poems in the X-language.” Such anthologies always rely on an accredited (by/with what powers?) editor who promises “only the best.” This approach itself has become a vitiated one given that a core move of 20th century art and writings into the present has been the move away from the single, self-contained work that claims “masterpiece” status. “Master” — just think on that word and all it entails ideologically…

The volume is dedicated ‘To those poets of the Maghreb and the Arab worlds who stood up against the prohibitions.’ In your view, how has the so-called Arab Spring changed the demands for the translation of literature from North Africa?

This is a tough and complicated question or issue and one I’m not necessarily equipped to answer. But let me try to talk to this. The so-called Arab Spring was sparked by the first protests that occurred in Tunisia on 18 December 2010 in Sidi Bouzid following Mohamed Bouazizi’s self-immolation. I read somewhere that to give the event a wider historical context one of the first TV reports quoted the Tunisian poet Abu Al-Qasim Ash-Shabi’s “The Will of Life” — a work from the late 20s/early 30s, which we print in Christopher Middleton and Sargon Boulos’ translation in the anthology.

This poem, as well as another one by Ash-Shabi, “To the Tyrants of the World,” was quoted, chanted, sung, recited during the protests & marches in Tunisia, Egypt and beyond. We use, on purpose, not any of the available more literary or “poetic” translations of “To the Tyrants…” and which are in the main rather weak, but a decent prose rendering by Adel Iskandar, which NPR used while covering events on Tahrir Square.

We know the importance of modern media in the spread and the very tactics of the revolts, and I’ve often wondered in the first months of the uprising if Gil Scott Heron (who passed away in May 2011) — and who’s also the guy who said “The first time I heard there was trouble in the Middle East, I thought they were talking about Pittsburgh” — was able to watch some of the events and reflect on his famous “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised.” In that early seventies piece he meant that people had to get off their couches and take to the streets, and that is indeed what happened, but at the same time, the fact that Tunis and Tahir Square were televised 24/7 and that the new social media, handheld, was able to both set up tactical communications between the participants and feed the frenzied image need of that junky TV set in your living room, was how these events “made it new.”

Difficult to say if poetry “made it new” in relation to the Arab Spring, though obviously from Ash- Shabi to the current generation of poets, much of the thinking that needed to be done has been done there. The Maghreb as a multilayered cultural space with both strong oral & written media has worked toward a possible liberation, first from the colonizers & then from the illegitimate totalitarian regimes that followed and were abetted by the ex-colonizers, all through the 20th century. From the lyrics of a singer like Cheikha Rimitti to the acidly critical poems of someone like Amin Khan, we can trace this work, these demands for change, these criticisms of a static petrified cultural & political situation. So the dedication of our book “To those poets of the Maghreb and the Arab worlds who stood up against the prohibitions” refers not only back to those who did this and were suppressed by their culture and governments — some, like Mouloud Feraoun or Tahar Djaout were killed, assassinated because they spoke out — but also to the present poets and artists who are doing this.

But your question had to do with how the so-called Arab Spring has affected the demand for translations from that part of the world. Not much if at all — at least in the field of poetry. Oh yes, there is a demand for non-fiction books on Arab and Muslim matters, there is even a slight up in demand for fiction ( a good way to follow this is to check in on Marcy Lynx Qualey’s Arab Literature (in Translation)). Though the fact that demand for translations from those parts of the world is up, because of, first 9/11, then the Afghanistan and Iraq war, and now the so-called Arab Spring, should let us think carefully about this matter. I was talking about this in my 11/8 Brussels conference keynote, where I criticise the ‘official’ writing that has emerged from those circumstances and quote poet and translator Ammiel Alcalay, who said:

How are those of us involved in transference and translation to respond to such circumstances? What is our role in the politics of imagination and transmission? Have we reached a point where NOT translating, providing access to, handing down works from the Arab world might be more legitimate? When we decide to participate, how do we insulate and protect such works and ourselves, not merely from assimilation, but from collaboration [...] Writers and translators often wind up playing someone else’s game, and become complicit, perpetuating the same rules with new players. [emphasis mine - PJ]

Which leads Alcalay to conclude that no act of transmission is innocent and therefore demands utmost vigilance, a kind of vigilance, he goes on, “that recognizes, as the American poet Jack Spicer once put it, that ‘there are bosses in poetry as well as in the industrial empire.” We have to be aware that, for example, translating a major novel by an Arab (or other third) world author wrenches that work out of its natural habitat, plops it into an environment where it can only be read according to the latter’s rules (say, Kateb Yacine’s Nedjma, in relation to William Faulkner’s narrative universe, etc.) Or, more viciously as in the case of my translation of Abdelwahab Meddeb’s essay ‘The Malday of Islam’ which was nearly hijacked by DC rightwing think tank people when Daniel Pipes asked the NY publisher for first serialization rights and the right to “subedit” the extracts — I managed to fight this off after a quick investigation.

So, more and more I think that given that the right solution, which would be to tell people to learn the language so they can read the books in the original, is impracticable & bound to fail, we need to keep translating — but that maybe we should change our habits, and realize that it is also the translator’s duty to provide contextual materials, so as Ammiel puts it, “to protect against assimilation and collaboration,” something that “requires more than fitting newly introduced and revived texts into existing frameworks. Defining what information is for us, where it comes from, and where to find it becomes an essential survival kit.” An excellent example of this is the recent work of Madeleine Campbell who, besides translating a full book of poems by Dib, and writing some excellent essays on that process, also added writing which she calls “Jetties” and that bring such needed contextual information on the author and his culture to the Euro-American reader via performance, readings, assemblages of quotes and other materials by the author and beyond, that create a matrix of relevant information allowing for a reading of the translated author’s work on his or her own terms more than on the terms of the target culture. So yes, there is massive literary material that needs to be translated, and there is even more massive quantities of cultural materials that need to be made available.

More information on the anthology and other work by Pierre Joris can be found on his blog.

December 2, 2013

Azonto Americana

For a couple of years now, Azonto has been the new dance craze that you just have to do whether you are dancing to Sarkodie or Lil’ Wayne. There have been some imitators and perpetrators, but the real Azonto reigns supreme. (Sorry Naija, but that Alingo stuff ain’t cutting it. Those upright elbows pose a problem in the club.)

Azonto has been huge in Ghana, obviously, and the rest of Africa. Then it made its grand entrance to London and the United Kingdom with some help from the British-born Ghana boy Fuse ODG, especially with Antenna. It was cool seeing the London All Stars do their Azonto thing, but I was hoping maybe, just maybe, it might finally touch down here in the US.

My salvation might be at hand in the form of the production company, Level 7. It warmed my heart to see Azonto done right in front of the 1 WTC, the Brooklyn Bridge, and just plain Suburbia Americana:

One derivative of Azonto that may take its time getting over here, or just disappear altogether is known as Alkayida. For some reason, with that name, I think it might have some trouble gaining traction here in the US. It may be blasphemous for a Ghanaian to say this, but aside from the fact that the music its associated with is boring, quite honesty, the dance is just not that good. See for example:

With dances, there is always something new, whether they were classics like Zoblazo or a little more contemporary like Cat Daddy or my personal favorite, that chicken noodle soup with the soda on the side. I am still waiting to see some real cool dance come from white people, but for now, I’ll just have to settle with this. And this. Your move.

The loser mentality of white South Africans

The latest piece of mythological drivel on us South African whites was published in that most stoically smug of bourgeois publications, “The Economist,” with the title, “Braai the Beloved Country.” This piece (illustrated with the stock photo, above, taken 10 years ago) made the rather extraordinary claim that we have been politically and economically marginalized in South Africa since the inception of majority rule in 1994. Again the mainstream media are trying to force a victim/loser complex on White South Africa. All this pessimism is nauseating. We won the negotiated settlement and have been thriving ever since–let’s celebrate it for God’s sake!

All the naysayers from The Economist to Steve Hofmeyr and our Red October kin are simply full of nonsense; we despite the odds still manage to do rather well in “the Beloved Country.”

White South Africans need to stand up and take pride in our ability to maintain economic power and in some cases expand it across the continent, while being able to maintain undue political influence not befitting our meager numbers.

Not only have we largely gotten richer and lost our international pariah status, but we can now compete and win in international sporting competitions! Hell, we’ve even been able to convince people that diversity is ensuring that South Africa’s official opposition party has a white leader, non-racialism indeed! It’s even almost impossible to find one of us who will admit voting for the National Party and almost everyone and their aunt/uncle/brother/husband, seems to now have struggle credentials! We played our part in the struggle too!

Our propaganda is so good, that we’ve even convinced ourselves that reverse-apartheid is the affirmative action policy that means some of our kids can’t get into to the University of Cape Town (UCT) or that a triumphant form of non-racialism consists of the fact that the UCT Black Law Students forum has a white president as well as vice-president. We constantly bemoan the skills shortage, deteriorating infrastructure and the bad service in South Africa, but pale skin is still seen as interchangeable for competence and efficiency, black people still get viewed as affirmative action beneficiaries whenever they seep through the cracks to occupy a certain position in society.

And we can still wax lyrical about the good old days while indulging in that most sacred of rituals of settler colonial masculinity according to The Economist: the braai. No wonder we constantly wax lyrical about the wonders of the legal system and defend it at all costs when ‘judicial independence’ is threatened by the ANC while over 77.3% of advocates associated with the General Council of the Bar in South Africa (GCBSA) are male and 74.3 of these are white! Not bad, for a mere 9% of the population. We punch far above our actual demographic weight.

As for the claim, “Overall whites are politically marginal” – this is simply insulting; whites have more than ample representation from the crowd of ex-National Party politicians hanging around the ANC’s progressive business forum to the leader of the South Africa’s official opposition party to multiple cabinet ministers and more than several parliamentarian whites.

And let’s be honest here, we still run most of the top corporates in South Africa. Black South Africans own less than 21% of the JSE. Furthermore this new class of black capitalists now share our values, through a rather ingenious scheme inaugurated by both the Nats and our Anglophone bourgeoisie we managed to form a good working relationship with many of the ANC’s leaders in the 80s and later managed to put swathes of them in business. We even got all the lefty trade unionists to become good capitalists like Cyril Ramaphosa and Marcel Golding.

When good friends of ours like Trevor Manuel dropped our exchange controls, we got to move tons of money to the great banking centers and tax havens of the North. Hell we managed to send around 3 trillion rand out the country. We also got further license to make some money across the rest of the continent as Koos Bekker of Naspers (one of the men praised by The Economist) took full advantage of.

Some of us still have rather silly fears about the ANC and the potential for apocalyptic Zimbabwe-like scenarios, many of us lost quite a bit of sleep over the fear that Julius Malema when he was in the ANCYL was going to come take our land. But the ANC so far has showed itself to have a distinct bias towards those well off, they might take some of hard earned tax money to keep the poor alive, but they still spend half of our health budget on subsidizing our health insurance. Their policies don’t even seem to propose much more than the ambition to create a favorable business environment to track foreign investors and their solution to our unemployment crisis is to promote ‘entrepreneurship’ rather than take more of our stuff. Our chosen representatives in the DA even endorse the ANC’s new policy bible, the National Development Plan.

What’s the moral of the story then? We whites should be celebrating our achievements instead of denigrating ourselves and promoting a negative culture of entitlement among us. We should be celebrating the fact that we managed to come out of the political settlement on top, after we were forced by international pressure, sanctions, the black trade union movement and the UDF to unban the ANC and other liberation movements and to finally come to the negotiating table.

The Rory Peck Awards

The Rory Peck Awards, which took place on Wednesday, November 20 in London, are held to honor the work of freelance cameramen and women covering news and current affairs. This year’s finalists included two reports from Africa (Mali and Somalia), as well as pieces shot in Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Kashmir, and Syria.

Two pieces caught our attention: The report from Somalia by Ahmed Farah is called ‘Somali Justice‘ and looks at the death penalty and the practice of qisas (equal retaliation) in the semi-autonomous region of Puntland. The footage from Mali, which won the Rory Peck Award for News, was filmed by the British cameraman, Aris Roussinos and broadcast by VICE UK. Entitled ‘Ground Zero Mali: The Battle of Gao,’ the piece humiliates the Malian army, showing footage of their day-long battle with militant Islamists in the major northern Malian city of Gao, before they are eventually joined by French troops.

Here’s a short clip from ‘Ground Zero: Mali’:

You can watch the full film on YouTube or VICE’s website (link above).

And here’s a clip from ‘Somali Justice’:

Watch it in full here.

Although the finalists are not in the same category (‘Somali Justice’ was a finalist in the Features category), Farah’s piece is the better of the two. Roussinos’ report somehow managed to win despite the fact that his video camera ran out of memory at a pivotal moment in the battle, so the second half is essentially a slide show of still photos. In fact, the story shows the Malian troops as woefully unprepared, disorganized, and undisciplined, while glorifying the French troops, without whom Roussinos seems to believe the Malians would not have been able to win the battle. Yet conveniently for his argument, Roussinos’ video camera runs out of memory soon after the French join the battle. He is probably correct in his thinking, and the Malian troops do look rather out of their depth, but since there is not much footage of the French troops in action, the viewer can’t make an accurate comparison and has to take the reporter on his word. The report also showcases a tremendous amount of truly grisly footage, shot the day after the battle, of the corpses and severed heads and limbs of the Islamists (after all, no VICE news coverage would be complete without excessive and unnecessary images of carnage in the Third World).

‘Somali Justice,’ on the other hand, is a pretty significant piece of journalism, providing viewers with a rare and informative glimpse into a situation and part of the world that normally only receives minimal, lazy, and inaccurate coverage. Moreover, Ahmed Farah allows his Somali subjects to tell the story themselves — something that hardly ever happens in Western news stories on Somalia.

November 29, 2013

Weekend Music Break 63

We kick off our weekly installment of new music videos with Ottawa-based Mélissa Laveaux riding the crunchy electronics with flair on her new offering, ‘Triggers’, in a video directed by Terence Nance — remember also this other video he shot for her earlier this year:

Some trippy and transcendental downtempo music from YellowStraps (that’s Yvan Murenzi, Alban Murenzi, Ludovic Petermann and Thomas Delire) alongside Moodprint:

A boom-bap retrospective from Soular Razye, the Zimbabwean duo comprised of Depth and Synik. They’re working on a soon-to-be-released EP:

Eighties-style fashion and joyous dance styles adorn this video from Uganda’s Fantom Lovins:

Life suddenly makes sense when this song by Kalawa Jazmee’s Uhuru plays in the club. Oskido, who makes a cameo, is celebrating his birthday today. Bless up!

Still in South Africa, new work by Zola:

A catchy Bob Marley make-over from Senegal. Visuals courtesy of the illustrious Lionel Mendeix.

Robert Del Naja from Massive Attack collides with Congolese musician Jupiter on this subterranean robotic banger. The pair met on the Afrika Express adventure in 2012.

A visual and musical collaboration between dj Khalab and Malian talking drum master Baba Sissoko:

And to round it all off, a bit of kuduro never hurt anyone:

November 28, 2013

Bombino: Nomad, but much more

Bombino’s mesmerizing 2013 album begins with the sound of a revving engine, perhaps the guitarist’s cheeky way of saying that he’s going to take the listener somewhere really special. And so he does, via soulful, intense songs which center around his fabulous guitar playing. This album is full of contradictions: it is called Nomad yet about much more than nomadism; it is increasingly popular abroad yet not ultra-famous in his home country; it inspires imagination, yet complicates the global perception of the Sahara. It is music that reflects the changing contemporary situation in Niger, and the country’s complicated relationship with the rest of the world.

Bombino (also known as Omara Moctar, and born Goumour Almoctar) is a Tuareg musician from Agadez, the northern, Sahara region of Niger. Singing in the Tamasheq language, he’s part of a long lineage of Sahara rock musicians (such as Tinariwen and Ali Farka Touré). At a time when Agadez is increasingly depicted as a site of danger and terrorism, Bombino has created an album that shows the world the multiple, and often joyful sides of life in the region.

The tracks of Nomad feature guitar melodies, gentle vocals and percussion, and range from exhilarating (“Amindinine”) to blissful and lovely (“Iwidiwan” and “Tamidine”). As Arnaud Contreras recently pointed out in a post for this blog (picture of Bombino above is also Arnaud’s), life for people in the Sahara today is much more than nomadism. Despite this album’s title, songs on Nomad encompass themes that reflect multiple aspects of social and cultural life. “Zigzan” is about patience and “Tamiditine” is about the thrill of new love — here’s a stripped-down version of that song, recorded in Portland last year:

There’s also “Iwidiwan,” a song about friendship and homesickness, which resonates in a region where more and more people engage in migrant work. Bombino says he feels for the country’s struggling, nearly dead tourism industry, and promotes the stunning beauty of Niger in the rousing “Her Tenere.”

Bombino also has a compelling personal life story, depicted in Ron Wyman’s 2010 documentary, Agadez: The Music and the Rebellion, which profiled the musician and Tuaregs in Niger. In 2007, during a rebellion, Bombino fled to Burkina Faso. After the violence had waned, he returned to Niger, and in early 2010, he performed a concert in front of a mosque in Agadez, to celebrate peace and unity in the country. Today, Bombino is continuously outspoken about the need for understanding and dialogue. “What is important,” he says over the phone between concerts in Pittsburgh and Michigan, “is making connections between people.”

And he has made connections with people around the world: recently achieving great popularity in the international music scene, booking gigs across Africa, Europe, South Asia, North America, Australia and receiving media attention from NPR and Rolling Stone. In French, he jokes that the album title Nomad isn’t just about a meandering lifestyle, but it reflects his own constant international travels.

Writing about Bombino’s work, critics tend to stress two characteristics: its similarity to familiar, American artists, and its ability to “transport” the listener to the Sahara. Reviews often lead with the fact that Bombino collaborated with Dan Auerbach (of the rock/soul band the Black Keys) to produce this album in Nashville. These comparisons are there: yes, any fan of the Black Keys will love Bombino. And yes, this album shows the dynamic, exciting work that results from fruitful international collaborations, and fusions of soul, rock and blues. Yet — for Bombino’s charming presence, moving melodies, for his role in contemporary Tuareg society, his work is so special, it deserves recognition beyond constant comparisons to American rock icons. He may have Hendrix-esque moves, but he’s more than the “Hendrix of the Sahara.” Although listeners may feel transported to somewhere else, this music also tells the stories of Saharan culture more complex than the ones in the popular media.

Arnaud Contreras also highlighted that Bombino enjoys an enthusiastic fan base among youth in the Agadez region of Niger, suggesting that Bombino’s energetic dance moves and stage presence are perhaps the most admired and emulated today. In his New Year’s Eve concert last year at the Niamey’s swank Gaweye hotel, the dance floor was packed with youth dressed in their best and brightest, grooving to his sounds into the morning hours.

However, interestingly, despite exploding international fame, Bombino isn’t necessarily a household name throughout Niger, particularly in areas that are Sahel rather than Sahara, and in communities where the Tamasheq language isn’t widely spoken. A randomly selected college student at Niamey’s Abdou Moumouni University isn’t certain to know his name. He does not appear on local television as much as other Nigerien artists, like Tal National. Bombino’s growing popularity throughout the world, yet scattered popularity throughout Niger, reflect global inequalities in access to media. While listeners around the world can quickly tune into and adore his music via Spotify, all youth in Niamey don’t necessarily have access to technology that allows them to enjoy the work of musicians popular in other regions of the country.

Bombino speaks articulately about the challenges that Niger faces: striking poverty and the growing threat of climate change. Yet he is optimistic, insisting that despite the problems, the recent years have been among Niger’s best. Your year will be among your best if you download this album and start listening to it immediately, catch him for his remaining concerts in the USA, or watch out for him next month if you live in Australia. If you’re like me, and have the embarrassing habit of playing an album on chronic repeat; fear not, this music is so wonderful that no one will judge you for playing it over and over and over again:

The Afropolitan Must Go

My first thought when reading Taiye Selasi’s 2005 essay ‘Bye-Bye Barbar’ (or ‘What is an Afropolitan?’) was that this is the kind of sludge that would piss off Binyavanga Wainaina. One quick google and lo and behold: “For Wainaina, Afropolitanism has become the marker of crude cultural commodification — a phenomenon increasingly ‘product driven,’ design focused, and ‘potentially funded by the West.’” My second thought when reading Taiye Selasi’s ‘What is an Afropolitan?’, gesturing wildly at my MacBook in my local coffee shop, is that this is the kind of sludge that pisses me off.

I am angry for different reasons to Wainaina (though if he wanted to hang out sometime I’m sure we could have fun being pissed off together); I am not so much concerned with the commodification inherent in Afropolitanism as I am with the danger of reproducing a reductive narrative, one which implicitly licenses others to reproduce the same narrative because it has been confirmed by an ‘Afropolitan’ herself.

First, in ‘What is an Afropolitan?’ Selasi somehow manages to other her own perceived identity, as well as everyone else with an African parent or two — other, that is, against an original (i.e. a Westerner), as she describes the scene at a London bar:

The women show off enormous afros, tiny t-shirts, gaps in teeth; the men those incredible torsos unique to and common on African coastlines. The whole scene speaks of the Cultural Hybrid: kente cloth worn over low-waisted jeans; ‘African Lady’ over Ludacris bass lines; London meets Lagos meets Durban meets Dakar. Even the DJ is an ethnic fusion: Nigerian and Romanian; fair, fearless leader; bobbing his head as the crowd reacts to a sample of ‘Sweet Mother.’

Besides from adopting the tone of a National Geographic documentary, the text is clearly addressing a Westernised audience, explaining to them the strange ways and particulars of this tribe of ‘Afropolitans.’

Second, Selasi’s representation of Afropolitans in general (a group to which I too apparently belong and for which Selasi has taken it upon herself to speak) is weirdly prejudiced.

Were you to ask any of these beautiful, brown-skinned people that basic question — ‘where are you from? — …They (read: we) are Afropolitans — the newest generation of African emigrants, coming soon or collected already at a law firm/chem lab/jazz lounge near you. You’ll know us by our funny blend of London fashion, New York jargon, African ethics, and academic successes.

But what about the non-affluent African diaspora? What about insanely hideous brown-skinned people? What about white African natives? What about Africans who despise jazz?

“It’s a problematic term because it’s supposed to combine (the words) African and cosmopolitan,” says editor of Afropolitan magazine, Brendah Nyakudya, to CNN:

What it should mean is an African person in an urban environment, with the outlook and mindset that comes with urbanization — people who live Lagos, Nairobi, and have this world-facing outlook.

I agree that the term Afropolitan is problematic, but more than that, I don’t understand why a person with African roots in an urban environment needs a term to set her apart from the rest of the young people in an urban environment. Why separate African urbanites from the rest of the urbanites? How can that be constructive?

Personally I cannot for the life of me see what would justify grouping these people together, other than that they all happen to have one or more parent who define themselves as coming from a country in Africa, and that is not enough. What does a lawyer born and raised in Belgium or London or Inner Mongolia have to do with Africa? He may have one African parent. He may have been there this one time when he was seven. He may be brown-skinned. He may be interested in his African heritage. But shouldn’t the extent of that interest and how much it means to his identity-formation be left solely up to that individual himself?

For fun, imagine applying what Selasi is doing with Afropolitans to a group from another continent — for instance, everyone with one or more parent from Europe. Half of America would be “Europolitans! Coming soon in a country-music joint/blue-collar job near you, a group whose beautiful skimmed-milk skin and subdimensional booties…”

Third, exclusivity and the socio-economic dimension. Selasi discovers her African roots in her 2013 op-ed piece for the Guardian. This sentence caught my eye:

A waitress, passing me, nodded with meaning and I nodded equally meaningfully back, in that gentle way in which brown people often acknowledge each other’s presence. The instant’s exchange reminded me of what I often overlook: my minority status.

Ah, the gentle nod.

How many times have I sat nodding along for hours to one of President Obama’s speeches or Tiger Woods’ scandals. Or nodded down at the brown beggar in the street and then (gently) passed him by. Or rushed on to the Broadway set of Lion King to nod at every character in turn.

Just to make it clear; this is not an article about Taiye Selasi as a person. Neither is it about her background, her fictional work or whether or not she is on hugging terms with Binyavanga Wainaina. Yet, two implied suggestions balloon out of the above quote.

First, that there is some sort of inherent connection between all brown-skinned persons. We know something. We necessarily connect. As one of my critics has rightly pointed out, all group identities are constructed. However some group identities run away with us. Some become harmful, or even work against the purpose they were created to defeat. This article argues that the “Afropolitan” is just such a group identity. It is exclusive, elitist and self-aggrandizing.

The second intimation furthers the point; Taiye Selasi suggests that she has minority status. That she, as a brown-skinned person, has minority status. That she, as a brown-skinned person, in her personal, soaringly educated, well-off, dominantly white social circle feels sometimes like she has minority status. Fair enough. Race-based judgment is always bad.

But I can see an elephant in the room, and he has dollar-signs for eyes. She goes to Africa; “I could see myself in these African cities: a designer in the vibrant clothes, a screenwriter in the desert scenes, a poet in the rhythms. I began to say that I wanted an “I ❤ Heart of Darkness” T-shirt, and only half in jest.” This experience may have been an interesting personal journey. And “I ❤ Heart of Darkness T-shirts” would be cool. But it tells us something about the socio-economic status of the “Afropolitan”, at odds with her implied marginalization, as she earlier on in the same piece levels herself with the brown-skinned waiter.

The Afropolitans Selasi describes belong to a narrow class; one that economist Guy Standing would perhaps call the “technical middle class”. What is most appalling is that Selasi excites this class to take up battle on behalf of the rest of Africa (Bye-Bye Barbar). “And if it all sounds a little self-congratulatory,” (yes it does), “a little ‘aren’t-we-the-coolest-damn-people-on-earth?’ — I say: yes it is, necessarily. It is high time the African stood up,” (Stood up to whom? For what? How?); “There is nothing perfect in this formulation; for all our Adjayes and Achidies, there is a brain drain back home. Most Afropolitans could serve Africa better in Africa than at Medicine Bar on Thursdays.”

This type of call to action takes me back a few decades (or is perhaps an indication that the discourse has not moved forward) to the first wave of African intellectuals as described by Simon Gikandi in his ‘African Literature and the Colonial Factor’. This wave of intellectuals distinguished itself by attempting resistance but using the colonial language, feeling strong affiliations to the colonisers’ structures and institutions. A call to arms of African intellectual diaspora, of a certain socio-economic class, educated in the West, and ready to charge off and save Africa is, in this light, unsettlingly familiar.

That is not to say a doctor or lawyer is not needed in most countries of sub-Saharan Africa, and that there is not much to do by way of development. Yet the way in which we phrase this call to action is important. It needs to be precise, concrete, thought-out, sustainable, collaborative. It needs to be divorced from any notion of racial determinism, from lofty, vague rhetoric. These things recreate the structures that are a big part of the problem in the first place.

What is more, it needs to be recognised that having brownish skin and a gap between the front-teeth does not necessarily mean a person possesses a deep understanding (or any understanding) of any particular African culture, complexity, needs, ways of thinking, ways of thinking about thinking etc.

Fronting a constructed group identity such as the ‘Afropolitan’ backs-up a (still) reductive narrative of Africa and the African, which in turn continues to be an important part of neocolonial soft power structures. Afropolitanism may have been a useful construct at some point, but I feel it is time to outgrow it, for everybody’s sake.

As an individual who happens to have one parent from the African continent I am offended at being put in a group and perceived to have certain interests and affiliations because of the nationality of one of my parents.

I do not have a drum beating inside me. The motherland is not calling me home. “We” are not a one-love tribe, yearning for the distant shores of Africa, or indigo or whatever one imagines the African continent as these days. “We” are a random sample in a huge pool of disembedded, modernised, travelling global citizens who each carry with us a personal, unique jumble of cultural inputs and influences from a range of places.

In other words, we are like most people.

And the most equity-promoting, barrier-breaking, racism-fighting thing “we” can do is see ourselves as just that — part of the noble and most ancient tribe…of Most People.

* This is an expanded and updated version of a post that first appeared on Think Africa Press.

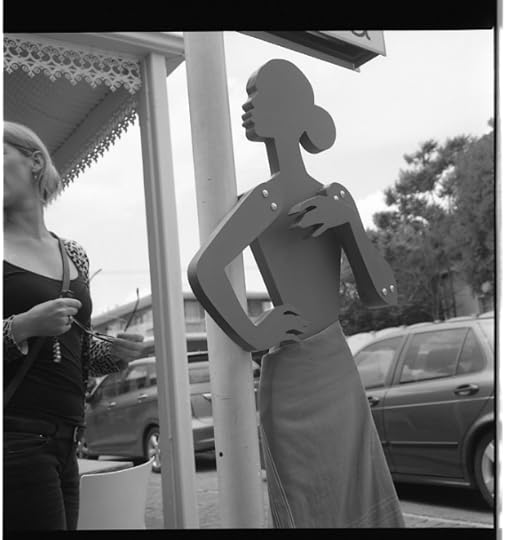

Street Photography in Johannesburg: Akinbode Akinbiyi

I love the way that Nigerian photographer Akinbode Akinbiyi works. I mean his approach to photography (see below) and the way that he uses his camera.

At least in the video below, he’s shooting with a Rollei Twin Lens Reflex (TLR) camera, using the sports finder. That immediately makes him one of my favorite photographers. I adore Rollei TLRs, and it’s tremendous fun to use the sports finder. The technique, like the camera itself, went out of fashion in the early ’60s, except among fans and eccentrics. (I’m both, I’ll admit.) Quick translation below the video.

I’ve come here to continue my aim in life which is to photograph big cities, primarily in Africa but also anywhere else. However, [I photograph] not only big cities, but also smaller cities, and even very small ones. / I work like this: I’m very open. I have no major themes, well, some, but they are not foregrounded. / The city [of Johannesburg] is very dense, [but] also very spread out…I find it very hard to capture but it’s one of the most important cities in Africa, and that’s why I really wanted to photograph it. What probably fascinates me the most are the opposites…that in a way you still sense apartheid in the city. / [He asks the shop owner on the street:] Maybe you know, there used to be a cinema in [the neighbourhood of] Mayfair [He asks a petrol attendant who gives him directions to the cinema]. I believe this here is the cinema — in any case it is still here…but the question now is how best to photograph this cinema. It’s hard! Very hard!

I mentioned that I like the way that Akinbiyi plies his trade. In another interview, he describes his approach to photography and to people as slow and gentle:

My philosophy is that you are quickest on foot. This may sound contradictory. When you walk you move slowly through spaces and by so doing you see more. I have been doing this for 40 years. I move very slowly and gently, I try not to invade other people’s spaces, while at the same time trying to take images. It is a sort of dance, a negotiation, meandering — a very sensitive way of moving through all kinds of spaces.

That’s my kind of street photography. The covert stealing of images and the macho posturing of so much classic street photography feels awfully old-fashioned in 2013.

You can read the rest of Akinbiyi’s interview, here.

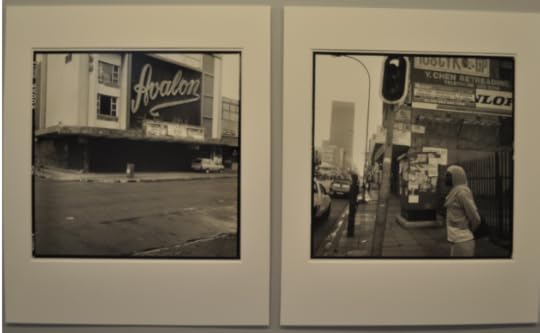

Akinbiyi’s new work, “Adama in Wonderland” (some examples below), was developed during his stays in the city in 2012 and 2013. He describes the work as “a wander through the contested streets of Johannesburg looking for, searching for its essential essence. Extremely fine gold dust floating ever so ephemerally in the evening twilight, down the grid-patterned streets of Downtown, out into the southern suburbs and up and away into the northern counterparts, and in no way forgetting the equally contested streets of the western and eastern suburbs.”

Johannesburg, 2012 (Image © Akinbode Akinbiyi)

Parkhurst, Johannesburg, 2012 (Image © Akinbode Akinbiyi)

(Image © Goethe Institut Johannesburg)

(Image © Goethe Institut Johannesburg)

Akinbiyi’s photos will be exhibited at the Goethe Institut Gallery in Johannesburg, South Africa, from today, 28 November (the exhibition opens at 6:30pm) until 31 January 2014. Details here.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers