Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 438

November 27, 2013

Before They Resurrect the Noble Savage

As history and our collective experience reveals, so much of a photograph’s meaning is not captured within its frame. What is not confined to the frame is the social environment within which the image was created. This social context can profoundly affect the way we experience and interpret images and shouldn’t be forgotten, particularly with images that are thrust at us by the media. Such images are complimented by thoughtful meditation to balance our initial emotive reaction.

The ethnographic portraits of British photographer Jimmy Nelson that have been making the rounds recently may appear upon first glance to be simply captivating in their beauty. Indeed many prominent media websites have discovered and promoted his work including CNN, Time and the Daily Mail. In the images, members of various ethnic groups from around the world are depicted to convey the idyllic aesthetic of the lives they supposedly lead in their rustic and isolated environments. The Mursi are found nude and painted in Ethiopia’s rift valley, ochred Himba women are carefully assembled in Angola’s southern dunes, Maasai warriors emblazoned in their red cloth balance carefully on stones in the hills of northern Tanzania. All are immaculately posed in their majestic surroundings.

But that’s just it, the scenes have been deliberately constructed to capitalize on the photographer’s own vision of these groups. While such images certainly elicit awe and amazement, they can distract us from asking questions about their creation and the nature of their representation. A visit to the photographer’s website (beforethey.com) reveals more about his intentions. The message found there is this: let us, the tainted citizens of modernity, bask in the beautiful simplicity and cultural purity of these exotic people of color before they become corrupted beyond redemption by the burdensome complexity of our lives. While you’re at it, make sure to take special note of the photographer’s unique ability to tame these mysterious and wonderful tribes with his inexhaustible charm. And then, if you would be so kind, please produce your pocketbook and for only the modest sum of 6,500 euros you too can take part in this spectacular journey to the birthplace of mankind by purchasing the deluxe edition of the photographer’s book. Right.

By looking beyond the photographic frame and taking the social context of this body of work into account, a few observations come to light. The rhetoric Nelson uses to describe his images strongly characterizes the Western fantasy of the noble savage, whose ancient culture, unchanged for thousands of years, has been passed over by evolution. This is achieved by linking the romantic traditional aesthetic captured in the images with repetition, in his interviews and promo materials, of phrases designed to emphasize supposed authenticity such as “flawless human beauty”, “original human art” and “purity of Mankind”. Indeed the morose name of the project, Before They Pass Away, laments the loss of these supposedly untouched cultures.

Nelson suggests that inspiration for this project comes from the work of early 20th century image-makers such as Edward Curtis, a photographer who documented what he believed to be the vestiges of dying Native American culture. This style of documentation, aka “salvage ethnography”, imagines itself to be about the visual preservation of vanishing cultures. In practice, the intentions of Curtis and his peers were not malicious, though they approached their subjects with a paternalistic superiority. Jimmy Nelson explicitly mentions Curtis as an influence and makes reference to a new era of “classic photography”. It should also be noted that the works of both Curtis and Nelson were made possible by wealthy benefactors. For Curtis it was American steel man J.P. Morgan and for Nelson it’s the Dutch investment billionaire zoo-owner Marcel Boekhoorn (who also produced a film about hapless Dutch animal handlers lost in South Africa called Zoop in Afrika – we’ll leave that for another post). One important distinction between Curtis and Nelson however, is that 100 years ago, the concept of the “noble savage” was accepted by academia and popular culture, whereas today it is widely considered to be condescending nonsense for assuming a lack of sophistication and for falsely justifying an idealized supremacy of Western cultures. This is the tradition Nelson has chosen to align himself with.

Like Curtis before him, Nelson produces artificial images, dressing subjects in traditional attire, stripping them and their environments of objects deemed to be foreign and posing them to his liking. He is in effect, attempting to determine what is authentic as an outsider, denying the dynamic histories of the people he stalks. We see this firsthand in the pilot for a proposed TV show (Nelson fancies himself a reality star), travelling with him to the island nation of Vanuatu to see the master at work. In one scene, the show’s narrator describes a highly active volcano called Mt. Yasur. The narrator goes on to explain that the “population believed it would anger the spirits if anyone climbed the mountain.” Guess where Jimmy Nelson decided he wanted to photograph men and boys from the nearby Yakel village? Despite the visible anxiety of the Yakel models at the constant rumblings and explosions of the volcano, Nelson assembles them at its very rim for a series of images. This scenario of cultural disregard is repeated in various forms throughout his work, the final visual products being Nelson’s own interpretive gaze rather than the self-image of those that appear in the photographs.

The promotion of Nelson’s collection is significant as well. The images are backed by a slick marketing campaign with a level of obscene narcissism reminiscent of the infamous journalist turned “explorer” Henry Morton Stanley. It was Stanley who trekked through the wilderness of several African territories in the second half of the 19th century looking for the famous missionary Dr. David Livingstone. With tremendous self-aggrandizement, Stanley published glorified (and somewhat fabricated) stories of his exploits in Western journals while neglecting to mention the trail of disease and destruction he left in his wake. Apparently mimicking another of his heroes, Nelson takes a page out of the Morton Stanley playbook in the way he presents himself. His beforethey.com website, through dramatic, exaggerated statements, attempts to cultivate for the photographer an image of legend. It declares, “Hunters, fighters, nomads, Jimmy Nelson enchanted them all.” And, “Jimmy Nelson a gatherer of images, collector of truth.” It might as well say, “Jimmy Nelson, the world’s most glorious tribe whisperer.” Rather than establishing Nelson as a hero figure, what these messages convey is that Nelson is more concerned with making a name for himself than the conditions of the people he has photographed.

The most poignant observation raised by this body of work however, is not about Nelson, it’s about ourselves. That this photographic collection was so readily and uncritically celebrated by such a large audience in the media, the photography community and beyond is troubling and requires reflection. We are no longer in the golden era of salvage ethnography. At this point we know that exaggerated, exoticized representations of any classification of people carry with them a subtle condescension and a false force of othering. Yet, why is a critical eye not applied by many viewers of Nelson’s work? What is this strange admiration of authenticity that romantic “tribal” images readily tap into? Do they make us feel more advanced? Do we need to counter the perceived boredom of our “modern” lives with something exotic and different? The answer is not entirely clear.

What is clear is that we must train our eyes to place what we are seeing in context. We must become more visually literate. Nelson’s images can be admired for displaying human diversity and ingenuity — indeed the people he has photographed may even take pride in some of the images — however, let’s not strip people of their dynamic history with make-believe about purity. Peoples’ lives are not static, they never have been. And the noble savage marketing rhetoric coming from the brave explorer? That’s something we actually can encourage to pass away.

In the practice of photography, an image is on the one hand, an honest reflection of the visual cartography of an illuminated environment, but it is also fertile ground for spinning imaginative tales of an artist’s creation. Speaking at TEDxAmsterdam in early November, Nelson encouraged his audience to “look closer” as often “things can be very different than they seem to be.” When contemplating “tribal” images in the media, it would be wise to take his advice.

Wangechi Mutu in conversation with Trevor Schoonmaker

Trevor Schoonmaker: Let’s start at the beginning…can you tell me about your first artistic impulse?

Wangechi Mutu: From a very early age, I was an obsessive-compulsive drawer. Because my father owned a paper distribution company, I always had a lot of paper around.

TS: And that was in Nairobi…

WM: We lived in this one house until 1976, and I know that I used to draw so much, I’d run out of paper, and I’d end up drawing on the wall even though I clearly remember being told, “Do not draw on the wall.” But I just would go berserk and continue drawing, and so I was always battling my dad, asking him to bring more paper home […]

TS: So when and where did your career consciously begin? What was the impetus for leaving Kenya to go to high school in Wales? Were you already thinking about an artistic career or just about getting out of Kenya?

WM: My impulse to leave Nairobi was related to the fact that I was already a young artist, at least in my understanding of what an artist is. I already sensed that I was not going to be a desk-working person, or in the kind of professions that are seen as more stable or regular. I just knew it wasn’t for me. I was more interested in all of these avenues that allowed me to explore, to make things, to interact, to stay in constant motion, exploring ideas but also places. I was interested in travel.

I left Kenya in 1989 to attend high school, but I had actually been to Europe when I was fifteen with the school choir at my convent school. We went to France and Switzerland, and we sang and visited all of these cathedrals and churches that were virtually empty except for maybe half a dozen, a dozen at most, really old European folks who were so happy to see all these little African girls singing African versions of Catholic songs. We were very lively. We had a lot of fun. Of course, it was the first time most of us had left Kenya, but it made me want to leave and go to see places.

So by the time I was sixteen, dabbling in theater and kind of a restless teenager, it didn’t take me long to agree to apply to an international school […] My career — my artistic thing — has to do with seeing things outside of the box, feeling myself to be a person who is a little bit outside of the norm.

TS: And you felt that already in Kenya?

WM: Yeah. I felt that in my family much earlier. I remember enjoying getting out of the house to go to school, and my mom saying, “You’re so happy when you’re leaving the house.” And it was true. The house had become a very confining space for me for many reasons […] So I went to Wales and finished school in two years—by 1991 I was done. I came back to Kenya […] I was an artist, and I knew it, but I was trying to fit the idea of being an artist into the idea of being an adult who takes care of herself, who doesn’t rely on her family. There are not that many options in Kenya, so I was trying to figure out what I would do. I knew I couldn’t be an artist who makes things for the tourist industry — curios, jewelry. None of that was interesting to me, but that’s a big part of the, quote-unquote, art scene in Kenya.

I knew I didn’t know enough about contemporary art because I had studied art at my I.B. school, so I knew there was something out there that would afford me an opportunity, but I didn’t know what it was.

TS: When did you first become aware of contemporary African art as we think of it today?

WM: Well, there were some galleries — I always went to Gallery Watatu and Paa Ya Paa. The National Museum has art-related shows that tie into the exhibitions. It’s more like a museum of natural history, but they also show art.

I was aware of contemporary Kenyan artists, most of them older men who worked like folklorists, interpreting a lot of mythology and folktales through painting and sculpture. Even that was a disconnect, because while I understood what they were doing, I didn’t identify with them as strongly as I would have liked to, even though I really appreciated their work. But African artists, I hardly knew of any, to be honest.

TS: When did you start to see work by African artists that you did respond to? Was that in New York?

WM: In New York, ironically, you know, in the early ’90s. Richard Onyango, one of Kenya’s big painters, was one of the first shows I saw […]

TS: So you were at Cooper Union but you attended Parsons before that […] And did you go straight from Cooper Union to Yale, or was there time between?

WM: I had time in between […] I found myself in that space again where, well, I knew I was a visual artist but I didn’t know how to get started. You know — I have work I want to make but I also want to live and exist in New York City, pay my rent, so the two things fought each other. I decided I needed a couple more years of dedicated art school, art time, where I wasn’t chasing the clock or running in the rat race. When I left Cooper, I was very responsible. I paid my bills on time. I was living better than I had the entire four years before that. I wasn’t impoverished anymore, but I didn’t make any art, or very little. I had a hard time leaving work and going home to make art. I thought I could; hourwise, you feel like you can slip in four hours of art making, but in terms of energy and your state of mind, it’s not that easy.

You have to stay vulnerable to this thing within you that causes you to make art. You can’t approach it with just […] your head. You have to immerse yourself, and I knew graduate school would allow me to do that. But I also made a strategic decision to pick a grad school that had the right name, quote-unquote. You know, I think coming from a poor country, one of the advantages you have is that you are wired to understand that there are not enough safety nets out there to catch you. You really do have to set yourself up for being successful, self-reliant, figuring things out for yourself, because the state is not going to do it — we don’t have that option at home. If you don’t have family money, or it’s running out, then you’re on your own. The art thing is part wizardry and part practical stuff. I had to figure both things out — I picked Yale.

TS: You must have had a distinctive portfolio from Cooper Union to make that possible.

WM: I don’t know if I had a distinctive portfolio, but I learned a lot at Cooper […] By the time I got to Yale, I was ready for the rigorous critiques. And I also had experience being, well, a cosmopolitan African. I wasn’t provincial. So I think it was the good training, you know. I had a lot of confidence at Cooper.

TS: When did you start to develop your own unique artistic voice? […]

WM: Before grad school. At Yale, I just tried everything out because the resources and equipment and infrastructure were there. I did things in wood. I made videos. I sewed. I wrote. I drew. I did a variety of things in the sculpture department that I consider important to what I do now — they were very much about experimenting and really honing down to what I found to be my preferred way of working. But if you look at some of my work from grad school, you wouldn’t say, Oh, there’s a Wangechi piece […]

TS: Your work encompasses such a broad group of references — you borrow from everything under the sun — African culture, medical history, contemporary fashion. You have a special way of pulling everything together, of creating connections and critiques, to make these disparate pieces work as part of a “maximalist aesthetic,” as you’ve called it before. Can you say a bit more about how you weave meaning out of all of these threads?

WM: You know, I think what happens is that I use what I have right there around me […] I’m going to go through my magazines. I’m going to use a particular kind of paper. I start to see aesthetic and formal connections in imagery that actually have a lot to do with the content. One choice determines the next set of choices. And ultimately I come up with an image that I like and want to see, one that is lovely to look at but also very meaningful, that makes the connections I’m reaching for tangible. […]

TS: One of the central themes of your work for me is hybridization: […] male/female, white/black, human/animal, Africa/Europe, or even hand versus machine and the human race and Earth as an ecosystem. […] What are the core issues that keep rising up for you?

WM: I have different themes, and I mash them all together. One of the things that I’m focused on is finding new ways to interpret the female portrait by questioning those qualities we look for when we identify something as “woman,” or even “beautiful.” What do the words mean? And how are they particular to, and part of, different histories? We sort of assume that we are saying the same things and so run the risk of ignoring, of negating, the existence of people when we homogenize them.

TS: […] [A]re there certain sources you find yourself going back to over and over again?

WM: Fashion magazines, while they don’t contain any kind of critical examination of the content, tend to be printed on great paper and with such clarity that the bits and pieces I pull out of them are ironically more helpful than many of the magazines that support issues that I politically or emotionally care about. So I go to fashion magazines again and again.

TS: Their lack of critical heft works to your advantage?

WM: There’s this inverse thing where I go to these magazines for material and doing that allows me to critique them by breaking them apart and kind of vandalizing and dissecting them. I pull apart their structure, literally and physically and conceptually, and then reinterpret it for my own purposes and my own interests.

And while I can’t say that I’m a huge fan of National Geographic, the magazine is one of the biggest ingredients in my work — and I have such a problem with its approach. At base, National Geographic is very colonial, still has a deep colonial kind of patina on it. But they have some of the best photojournalists working on their team and run the best-quality mass-produced photographs, images that relate to scientific research, ethnography, and a bit of fashion, even though it’s usually tribal and traditional. I enjoy looking at those things and then reconfiguring them because I have a problem with the way they write about the world and what they choose to focus on. So it’s a playground for me to sort of mess around with that. But of course, that’s made possible by the fact that the magazine is reproduced so well, great paper, great printing.

TS: What better way to critique a colonial perspective on the world than to use its own materials and imagery?

WM: Yes, exactly. It’s a gift, an affordable gift.

TS: Thank you, National Geographic. What are your other inspirations? Are there any writers whose work has been particularly influential?

WM: There are many. I loved the first time I read Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels and A Modest Proposal. And I admire Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things, but also her activist work, like The Cost of Living. I listen to a lot of Toni Morrison interviews, and I’ve read The Bluest Eye and Tar Baby. […]

TS: And what about music?

WM: I’m really inspired by music. I try to go listen to a lot of live music, see people perform. Things happen in front of your eyes that, no matter how rehearsed, you can’t predict, and I think that’s very courageous and interesting as an art process — there’s an authenticity and immediacy to stage art, whether in music or theater. As a visual artist, you get to tidy things up, at least to a certain degree, so I’m drawn to music and performance for the dynamic time element and because it’s finite but stays in your memory, in your nerves, afterward. Visual art doesn’t behave for an audience exactly like that.

TS: […] Who has stayed with you? Because everybody’s taste changes.

WM: Who has stayed? That’s a great question. Tom Waits has stayed. He’s still in the collection. Björk doesn’t go back super far, but she has stuck with me for over a dozen years. I think she’s amazing. I would still buy every record she makes. Fela reaches all the way back, but Fela — there was this gap or this lull, you know. Way back as a child, I inadvertently listened to Fela on the radio and learned to understand Fela without even being taught how to understand him. And then he came back, in many ways due to the Black President exhibition.

Something else that has stayed with me — not an artist but a musical form — is Bhangra. Bhangra was bursting into life in New York at the same time I arrived, largely because of DJ Rekha. I remember thinking that both Fela and Bhangra were ghetto music back home. Fela was being listened to in Kenya, but not by middle-class kids like myself. And Bhangra was all over the movies and in the Indian stores. But in New York I discovered it was really everywhere. It was heartwarming because it was so familiar, and I got it; I knew where it was coming from […]

TS: So what musicians are you listening to now?

WM: Abdullah Ibrahim, Nina Simone, Just a Band, Björk, Fela, Asa, Jason Moran, Buika, Meklit Hedero, Tricky, Sigur Ros, Baloji, Glenn Gould, Oumou Sangare, Imani Uzuri, Santigold […]

TS: [In] your collages you create spectacular aggregates of animal, plant, human, machine. But much of your work also has a sense of location, even though it’s completely fantastical and made up. In your installations, for instance, you’ve been creating trees and root structures. Can you say a little bit about how you think about landscape?

WM: Landscape is important, but I’m creating a fictional landscape, so it’s kind of a romanticization of certain aspects of nature. I don’t try to strictly replicate things that I love but tease out ideas that are mythologically and historically important to me. Trees play a big role in my work, as a Kenyan, as a Kikuyu, as a person who loves plants. I love and need to look at nature. My mother is a gardener, and I was raised in a beautiful natural environment. I am very drawn to things that grow and change. I have a garden. I think about plants and animals that communicate very slowly but distinctly, and how they exist.

I think about those things in connection to my content — plants and animals are in our world, existing with us, and they have just as many rights to be here as we do. I think about that when I work them into bodies — human bodies, mechanical bodies. I’m also alluding to the fact that there is this connection — this deep connection — that we all share because we all come from the same place.

And trees are the matriarchs, the big mamas, of the forest, and they intrigue me. So I use a lot of them. Their form, the sculpture of trees is also very interesting to me — the roots and branches, the structure of a tree, how it holds itself up.

[…] [O]ne of the main things about a tree is that it plays such a central role in the creation stories that I learned, both Christian and Kikuyu narratives of creation. There is the tree, an original holy tree. And in Kikuyu, it’s actually the Mugumo tree, which is this big fig tree, and it’s the tree from which we were all birthed. You’re not supposed to cut it down or desecrate it. And the tree is female in my mind — I’m not sure why but I turn everything I like into a female — so it’s got this matriarchal quality to it. So that’s why the Mugumo tree keeps appearing.

And I always think that there’s something about trees that feels like they’re the original gallery space, the original place of worship and awe — where we brought our meager and modest human creations so that we could think about divine and unknowable things. I’m a city girl, so I didn’t grow up in the rural area where my parents grew up but still the reverence for trees is there. The Kikuyu lived in a very wooded, green, hilly area, but the trees were cut down due to development by the colonialists, who insisted on replanting fast-growing European trees that weren’t native to our land. So these trees not suited to the environment grew to full height in ten years as opposed to the thirty years it took for the original trees to reach their great height. It’s such a metaphor for what was happening at the time. And, of course in our area, the people who are replanting these trees were the Kikuyu — my people. They were forced to eradicate the indigenous flora and replace it with eucalyptus forests, forests of trees that don’t belong to our region, that don’t hold the soil, that don’t fit in the ecosystem.

* Interview conducted in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, September 2012. Excerpted from an interview that first appeared in Wangechi Mutu: A Fantastic Journey (Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, $39.95, 2013). Trevor Schoonmaker conducted the interview, edited the catalogue and organized the traveling exhibition. He is Chief Curator and Patsy R. and Raymond D. Nasher Curator of Contemporary Art at the Nasher Museum. Used by permission.

Wangechi Mutu: A Fantastic Journey, Mutu’s first survey exhibition in the United States, runs until March 9, 2014 at the Brooklyn Museum.

November 26, 2013

My Favorite Photographs: Arnaud Contreras

The Saharan society is changing fast. Still a beautiful desert but not just that. Most populated cities such as Tamanrasset or Timbuktu are microcosms revealing all the problems of those former touristic regions: threats of terrorism, traffics, illegal migration, pressures on cultural and natural heritages. The only ways to escape this harsh reality for Saharan and Tuareg youth are cybercafés, mobile phone culture, festivals and soirées guitare (“guitar evenings”) celebrating their guitar heroes, the “Ishumar”, such as Tinariwen, Terakaft, Tamikrest, Bombino and many other bands. In their songs they celebrate the link between desert nature, old poetry, and of course women, whose role is essential in their society. Some texts may seem like calls for rebellion, but mainly those are calls for a self-consciousness as a people, of their identities.

In Europe, the Saharan diaspora tries to keep alive the friendly link between the Sahara and the Western world, organizing concerts and parties. Since 1999, I’ve been traveling each year to the Sahara region (Mali, Niger, Libya, Algeria, Burkina Faso, Mauritania) to document those changes, making documentary films, radio documentaries and photographs. After working on Saharan heritages and cultural roots, I decided to focus on contemporary Saharan culture. Going back to Europe, I was fed up with the false “mythic” representation of Saharan people: camels and blue veils… My Tuareg, Berabich, Maures, Songhay friends find themselves living squarely in the modern world, not outside of it. They spend a lot a time on Facebook or Twitter, exchange files via bluetooth. Together, we listen to rock, techno and pop music. Of course we talk about the sad situation of refugees and about the foolish terrorists who take hostage a whole region and its population. But most of the time, our exchanges are about culture, the situation in the rest of the world, cars, girls… just as in the Western world. Through this documentary work, a book and an exhibition will come, I want to give a testimony of their culture. Veils and camels… but not just that. Here are five of my favorite photographs, and some words on what they mean to me.

The first image, above, I love because it shows a part of what’s happening in the Sahara nowadays. Even if western media talk about strong fighters on both sides of the current war in Mali, women are still ruling. In the south, they created networks to help refugees, in the north, they are involved in protests, diplomacy, communication. I have a lot of respect for them. The man on the left is a Tinariwen band member. Without women and their poetry, Tinariwen music wouldn’t exist. The Kidal band Tamikrest honored women by naming their new album Chatma (“Sisters”).

Since 2001, I heard much negative talk in the Sahara about T-shirts with Osama Bin Laden’s face on them. In Europe, you’d read that “Bin Laden is a hero in the Sahel.” When I saw this kid at a local festival in the deep south of Algeria, we laughed together.

He told me, ”It’s just a fashion thing, nothing else, just like wearing one with Che Guevarra…or Obama.”

One night, Malian diva Oumou Sangaré was singing in Tamanrasset. It was the first time in years that I saw so many illegal migrants taking the risk to appear in public, singing, dancing. A rare moment of joy.

An estimated 20,000 African migrants are living in the biggest city of southern Algeria. Most of them work three to twelve months in Algeria or Libya and then go back to their homelands in Mali, Niger, Cameroon, CAR or elsewhere. According to researcher Julien Brachet, only 3% of the migrants want to go to Europe — a very different view to what we usually get to read in European newspapers who can’t stop talking about migrants invading Europe.

I spend a lot of time with Saharan rockers, with their family, friends. Tinariwen, Terakaft, Toumast and Abdallah Oumbadougou — this first generation of blues-rock musicians in the region mostly sing in a calm way when they’re on stage. Bombino caused a revolution a few years ago by his Hendrix way of playing guitar, of moving and jumping on stage. Always a smile on his face.

Funny to see how everybody in the region now copies his sound, his behaviour. 2014 will be a year of loud guitars and distortions in Saharan music. Perhaps a link with what’s happening in the desert. Sahara rocks!

In a traditional Tuareg tent, in the middle of nowhere, I came across these rapper kids. This generation claims its own identity, connected to the world via mobile phones, Facebook, Twitter.

Many people associate Saharan society with nomadism. But most of them are already a second or third generation to live in cities or villages. Nomadism still exists in remote regions, but is no longer the only way of living in the Sahara. Kids are proud of their nomadic roots, but are also aware of what it means for the central powers that be: nomads don’t own land and they don’t have one word to say on mining permits for the land they inhabit, those are decided on hundreds of miles away. This generation is fighting for ownership and rights to their land.

This is the 18th installment in our “5 Favorite Photographs” series in which we ask photographers to select five of their favorite photographs and to describe what brought them to make the image, and what they were trying to convey. Previous features here. You’ll find more work by Arnaud Contreras on his personal website and on his Facebook page.

The death of Oury Jalloh

One of Germany’s most enigmatic post-war lawsuits will have to be reviewed. This post is both a chronology of what is sufficiently proven and a list of the numerous crudities that remain.

What is for sure can be summed up in one sentence: On 7 January 2005, Oury Jalloh, an asylum seeker from Sierra Leone, burned to death in a police cell in the city of Dessau.

The narrative that has dominated public dialogue in Germany ever since has followed the official version of events as they were uttered on the very same day by the police. It goes like this:

At night, police were informed by four women who said they felt harassed by Oury Jalloh as he asked them for their mobile phones so he could make a call. Upon arrival, the officers checked Jalloh’s identity. Jalloh’s papers were crabbed and he is reported to have vociferously opposed identification by the police. Therefore, the officers took him to the police station.

There, a doctor certified that Jalloh had an alcohol level of almost three percent. Instead of ordering him to be brought to hospital, the doctor declared Jalloh fit for custody. After being strip-searched by two officers, Jalloh was escorted to a cell in the basement of the police station where his hands and feet were tied down on either side – as recommended by the doctor for Jalloh should not “harm himself”. Against all regulations, Jalloh was left alone. Only every half an hour somebody went to check on him. The last control that is officially reported took place at 11:45am.

The officer on duty, who was sitting in a chamber on the upper floor of the police station, turned down the volume of the intercom for he said he felt disturbed by all the noise from Jalloh’s cell. He turned up the volume again after being asked to do so by his colleague. Both of them later stated that they noticed some kind of gurgling in the cell.

When the fire alarm went off at 12 o’clock, this was ignored by the police officer on duty. He later explained that the alarm had gone wrong several times in the previous years (technicians will later doubt this statement). A few seconds later, the alarm went off again.

As the firefighters arrived, they found Oury Jalloh burned to death, hands and feet still bound. The official explanation: Oury Jalloh used a lighter to set himself ablaze.

Ponder this: A dead drunk man, with his hands tied, sets himself on fire on a fireproof (!) mattress?

There is more: The lighter which Jalloh allegedly used was presented days after his death. It was not listed among the evidence. The video tape which documented the search of the cell stopped just when the body of Jalloh was removed – no lighter can be seen. Neither fingerprints or DNA nor residues of cloth were detected on the lighter.

In 2007, the prosecution brought charges against two police officers for alleged bodily harm resulting in death. Still, the prosecution assumed that Jalloh had set fire to himself. Two verdicts later, it is clear that it was unlawful to take Oury Jalloh into custody. The court imposed a fine of €10,800 against the officer on duty for involuntary manslaughter. Yet, many contradictions remain. For instance, new autopsy findings prove that Jalloh’s nose was broken and his ear drums ruptured. Jalloh’s death ultimately, though, resulted from a heat shock. Since Jalloh’s urine lacks hormones that would have been released in a situation of panic (noradrenaline), it is assumed that he was unconscious in the moment that he caught fire.

In December 2008, the other officer was acquitted of all charges. The judge stated:

Yet, we could not detect, what happened on that day [that Oury Jalloh died]. What I had to witness in this court was a state that is no longer under the rule of law. The police officers who don’t seem to feel committed to the rule of law have made a juridical clarification impossible. Those officers, who lied to the court, are people who have no place in this country as police officers.

Outside court, several hundred demonstrators called for full clarification of the case. Mouctar Bah, the initatior of the “Initative in remembrance of Oury Jalloh”, was targeted by the police. Bah was thrown to the ground and beaten until he lost consciousness and had to be brought to the hospital in an ambulance. The officers stated that they would no longer tolerate the word “murder” with regard to the case of Oury Jalloh, despite a court ruling from 2006 which stated that the police had no legal restraint that allowed them to forbid certain statements during demonstrations. Just recently, the “Initative in remembrance of Oury Jalloh” was accused of defamation. Wearing a t-shirt that reads “Oury Jalloh – this was murder“ is sufficient for an accusal.

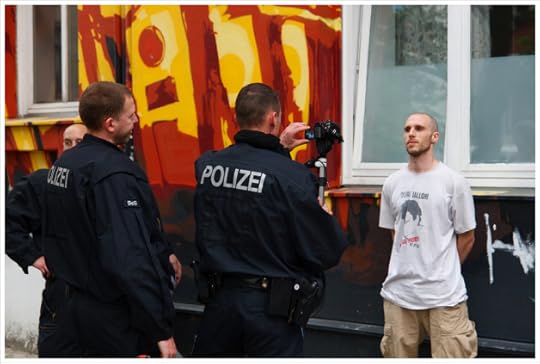

Mal Élevé, front singer of Irie Révoltés, is taken into custody during a demonstration for wearing a t-shirt that claims police to be behind the death of Oury Jalloh. (Image by Montecruz Foto)

Now, a new report, paid by the “Initiative in remembrance of Oury Jalloh” and conducted by an independent arson investigator from Ireland, reveals that Oury Jalloh cannot have set fire to himself. Nadine Saeed, a spokesperson of the “Initiative in remembrance of Oury Jalloh”, points out that at least three liters of combustive agents must have been used (see video here — Trigger warning: this video contains disturbing images).

Thomas Wüppesahl, spokesperson of the Association of Critical Police Officers (Kritische PolizistInnen), states:

It is normal these days that police officers back their colleagues by suppression of evidence or false statements. Part of this strategy is that certain documents and other exhibits are deleted, falsified, suppressed – or they magically disappear. The deformation of the German police is way more advanced than officials in the Interior Ministry and the Ministry of Justice refuse to believe. Those who speak out this inconvenient truth are marked down as conspiracy theorists.

It is against this background that many observers draw parallels to the case of the NSU in which the officials are also confronted with allegations of filibuster and numerous failures. According to Bilgin Ayata, a political scientist at the Free University of Berlin:

the disclosure of endemic racist structures among the police and state authorities has reached a degree in Germany that is appalling. In the course of the NSU investigations it has been revealed that policemen founded a German section of the Ku-Klux-Klan in the federal state of Baden-Württemberg, for instance. Moreover, the NSU inquiry commission of the German Parliament that examined for one and a half years the role of the German security apparatus in the context of the NSU provided plenty of evidence for widespread institutional racism. Nevertheless, there is still no engagement with institutional racism in Germany. Even the very inquiry commission that lists a plethora of instances in their 1000 page report, shied away to use the word ‘institutional racism’ in its own assessment. This indicates a resilient political unwillingness to confront racist violence and belief in Germany.

The murder of Oury Jalloh has to be evaluated in this context, yet the scope of its brutality and the very location where it happened carries all what we knew so far about the past decades to another level. I have been following the case over the years through the media, and for me, it raises the same question over and over again: how is it possible, that a man whose hands and feet are tied up in a cell, is burning to death in a police station and not one single officer comes to help? What is urgently needed is not only another court trial but a wider public debate about what is left of humanity in light of such inconceivable acts of racist brutality at police stations and elsewhere in Germany.

It was not the first time that someone died in that particular police station while in custody. In 2002, the homeless Mario Bichtemann was arrested and left in the very same cell where he was found dead the day after. Investigations did not lead to a conclusion and the officers were cleared of all charges. In 1997, another man was taken in custody to the same police station in Dessau. The morning after, he was found dead on the pavement only a few meters next to the police station.

“The judicial investigation of the case stopped just whenever it was getting interesting,” says Yonas Endrias, a political scientist at Berlin’s Free University and an afro-German activist who has long observed the trials in the case of Oury Jalloh.

In Amnesty International’s view, the National Agency for the Prevention of Torture is not adequately resourced and therefore not able to carry out its functions effectively and in line with the obligations under the Optional Protocol Against Torture (OPCAT). In 2010, the UN Special Rapporteur on torture quotes Germany as one example where the National Preventive Mechanisms (NMP) “are most obviously not capable of fulfilling their task.” The statement further reads that in Germany “the federal NPM is comprised of only one unpaid part-time person and a Joint Commission of the federal States (Länder) consisting of four unpaid part-time members, whose combined annual budget is not to exceed 300,000 EUR. This mechanism is evidently unable to ensure complete geographic coverage of all places of detention. Such approach to the implementation of OPCAT is counter-productive since it does not take the problem of torture and ill-treatment in detention seriously and sets a bad example for other States.”

The German government has long ratified the UN convention against torture. Yet, as Yonas Endrias complaints, “unlike for example in England, we have no independent committees which could control the police.” In fact, only very few complaints against police officers are ever tried in court. The majority of complaints is dealt with internally by the police. Amnesty International therefore demands independent police complaints bodies. Likewise, the Association of Critical Police Officers states: “At present, all of the supervisory systems work rarely or not at all. There is no shortage of role models for independently monitoring boards in Europe – a look to the UK or Ireland is sufficient.”

According to Amnesty International abuse and excessive use of force by police officers is a common phenomena. Many of those who suffer from this form of violence are “foreign citizens” or Germans of foreign decent. Political scientist Endrias says: “The judiciary is not colorblind. Despite a judicial ban on racial profiling, these ‘suspected independent controls’ remain common police practice in Germany.” Endrias concludes: “If, for instance, a white prosecutor had died instead, the situation in Germany would be totally different. It’s not a scandal because Oury Jalloh was a black asylum seeker.”

Remembering Nokutela Mdima Dube

For ninety-five years the remains of Nokutela Mdima Dube lay ignored in the Brixton Cemetery in Johannesburg. Similarly ignored were her contributions to the founding and development of a critical set of institutions – the Ohlange Institute, the Inanda Seminary, the Ilange lase Natal newspaper, and the African National Congress – and cultural practices – Zulu chorale music, the valuation of the education of women. Upon her death at age 44 in 1917, Nokutela, the estranged first wife of ANC founder John Dube, was interred without individual marking in the section of the cemetery marked “C.K.” (“Christian Kaffir”). Four years ago, Cherif Keita, a Malian-born Professor of French and Francophone Studies at Carleton College, a private liberal arts college in southern Minnesota, set himself the task of finding her grave and bringing together the far reaches of her family, while making her contributions and story more widely known by erecting a proper monument and making a film about Remembering. His documentation of his quest to unearth and celebrate her genealogy has produced a marvelous excursion into the genealogy of knowledge for his film’s viewers.

Here’s a trailer for the film:

Professor Keita began his investigations into South African history in the late 1990s, when he discovered that missionaries from the small town, Northfield, in which Carleton is located, had helped educate John Dube, the ANC’s founder. Keita developed an appreciation not only for these missionaries, who had been expelled from South Africa and ended their lives penniless in the U.S., but also for Dube, whose historical contributions had been overshadowed by the roles played in the mid-late 20th century struggles by Albert Luthuli and Nelson Mandela. Keita turned to documentary film as a vehicle to tell these stories, producing “Oberlin-Inanda: The Life and Times of John L. Dube” (2005) and “Cemetery Stories: A Rebel Missionary in South Africa” (2009). “Remembering Nokutela” is the third piece of his trilogy. All three of these films explore in understated but suggestive ways the complexity of the relationships between American missionaries and South African revolutionaries, and between Christianity and African pride, which unfolded over the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Remembering Nokutela offers multiple layers of investigation to the ambitious teacher. On the surface it excavates a long-buried story and honors the contributions of a talented and dedicated woman. Viewers learn that Nokutela was a talented musician who journeyed to the U.S. in the late 1890s, where she performed to raise funds to support the projects she and her husband were launching in the Natal province, a industrial education school for boys and girls on the Tuskegee model, the first Zulu-English newspaper, and the first anti-colonial movement, the African National Congress. Just beneath its surface, this film prompts a pair of fruitful conversations: why was her story erased from the historical narrative?; and how do we go about researching such a story?

Both of these conversations are interwoven with stories about women and by women, stories which ask viewers to consider the roles accorded women and claimed by women in South Africa. Dube and Nokutela never had children, which Keita suggests led to their estrangement and, ultimately, her replacement in the South African liberation narrative by Dube’s second wife, Angeline Khumalo, with whom he had six children. The erasure of Nokutela from history, despite her significant achievements, suggests that women activists who did not fulfill women’s traditionally valued role of motherhood could be denied their place in the historical record altogether. At the same time, the filmmaker is only able to reconstruct Nokutela’s story through the oral narratives provided by her great grand nieces. Although she had no sons or daughters, no direct descendants, the pieces of her story were held by the granddaughters of her sisters and Dube’s second wife, and Keita goes on an historical treasure hunt to find and compose those pieces. His quest brings these women together in the present, some to meet for the first time, some to heal longstanding enmities and alienations, all to celebrate their common ancestor’s accomplishments. Seeming at times like a trickster figure, Keita moves in and out of these women’s homes and lives, collecting their stories but also enabling them to touch each other.

As the shared project of constructing an appropriate memorial for Nokutela and consecrating it with an appropriate ceremony takes shape, the film suggests the possibilities of transformation contained in what the African American writer Toni Morrison so aptly named “rememory.” Keita allows viewers to absorb the film’s final scenes, in which a Zulu chorale group performs the classic a cappella song Mbube (popularly known around the world as “The Lion Sleeps Tonight”). The ceremony attendees, mostly older women who have been sitting in folding chairs, move their bodies, and some get up to dance, dropping a cane or a crutch or dancing with a crutch. They seem filled with the music and with the community that remembering Nokutela has created.

Remembering Nokutela was screened as part of the first African Film Festival (November 15-21, 2013) at the Saint Anthony Main Cinemas) sponsored by the Film Society of Minneapolis and Saint Paul, US. The series was curated by a committee of dedicated Twin Cities scholars and cultural producers, eager to present a breadth of genres and geographies, ranging from Egypt to South Africa. For more information on the series, please see mspfilmsociety.org. The African Film Festival also reflects the expanding and deepening presence of Africans in the Twin Cities – Somalis, Liberians, Ethiopians, Oromos, Togolese, Nigerians, Egyptians, Palestinians, and more. Film, music, theater, poetry, literature, and politics in this community are increasingly reflecting their presence and expressing their agency.

November 25, 2013

Lilian Thuram’s Burden

Lilian Thuram isn’t just any footballer; he’s emerged as the game’s moral conscience, not just in the French-speaking world, but more broadly. So much so that recently a packed hall at New York University came to listen to him talk about racism in football … on a Friday night. Of course we went and got our picture taken (see here) with one of the best players of his generation. Born in Guadeloupe, his single mother took him and his siblings to Paris when he was still a little child. He played club football for Monaco, Parma, Juventus and Barcelona (in that order). He retired from playing in 2008 after being diagnosed with a heart condition. And after he scored 2 goals for France in the 1998 World Cup semi-final against Croatia, no less than Zinedine Zidane told journalists: “You write and write about me and Ronaldo, but you don’t even see that the greatest footballer of all is right in front of you: Lilian Thuram.” He’s also well-read and cites Aimé Cesaire, the Martinique poet and longtime Communist mayor of Fort-de-France, as his hero.

Two days before his NYU appearance he had told the BBC that white players have a responsibility to speak out when black footballers like Yaya Touré (recently the subject of racist chants by fans of Russian club CSKA Moscow) face racist abuse. “As a general rule we always go to the players who are victims of racism, and I think it’s the others who can change things … The action of not saying anything–somehow–it makes you an accomplice.”

When I speak about racism, or Yaya Touré or Kevin-Prince Boateng speak, everyone knows what to expect. But if tomorrow all the white players from Manchester City say that from now on if something happens we will refuse to go back out on to the pitch, and if the players from AC Milan, from Inter Milan and from all the big clubs say the same thing, you’ll soon see that we’ll find a solution.

Thuram’s challenge to the way racism is addressed in football, as in wider society, is profound: The failure of moral leadership against racism from those who are not themselves victims of it constitutes complicity and ensures that racism persists.

We’ve raised this issue before, and also criticized the connected problem of the way the media chooses to represent racism in football. Any report on racist abuse suffered by a footballer is invariably accompanied by an image of the black player concerned, but that simply isn’t an accurate representation of racism. The abuse they suffer, and not their mere presence on the pitch, is the story and ought to be the focus.

On stage, Thuram was interviewed by the American soccer writer Grant Wahl, who made a go of it and guided what could otherwise have been a tedious affair of platitudes and speechifying, into an interesting conversation. Thuram was in good form and recalled, for example, an incident from his time at Parma when Lazio wanted to sign him and sent their infamously racist Ultras to convince him. They assured Thuram that he would be spared their monkey chants and bananas. In effect, their pitch to him was: you’re so good that we’ll even put our racist abuse on hold if you’ll join us. He signed for Juventus instead.

But we became especially interested when the conversation shifted to the recent spate of racist incidents involving European fans. Wahl asked whether, like Yaya Touré, Thuram would advocate for a boycott by African countries and black players of the 2018 World Cup in Russia if the country failed to deal with the issue.

Some background: A boycott seems justifiable given the wide acceptance of racist behavior among Russian fans combined with the denial by Russian sports authorities/administrators to deal with racism. See the reaction by CSKA’s manager, for example. As for the efficacy of boycotts, the historical record suggest it’s not such a bad idea: Remember when Kwame Nkrumah urged African football associations to boycott the 1966 World Cup in England. Until then the sole African representative at the final tournament had to play the an Asian or European team for a place at the finals. The result was that for Mexico 1970 FIFA Africans teams were assured of one direct slot just for them (which has since been increased to 5). And who can forget how sports boycotts messed with the resolve of South African whites.

But, there are also good reasons why boycotts don’t work. Not everyone you think will or should support it, will comply. At the Olympic Games in Montreal (boycotted by African nations) or Moscow (boycotted by the US and its allies), those attending went on with the business of competing as if nothing had happened. Also, the South African boycotts were undermined by “rebel” teams traveling there or English football players (Kevin Keegan, Roy Hodgson, come to mind) going to play club football there in Apartheid’s leagues. And who is to say some smaller and weaker African footballing nations won’t see the absence of say Côte d’Ivoire (who Yaya Touré plays for) as their chance to get to the World Cup.

But Thuram added his own criteria. He’d only push for sports boycotts or the cancellation of international tournaments hosted by countries who have clear discriminatory policies based on basis of race, ethnicity, origin, and so on. Russia was not officially promoting xenophobia or racism, he argued.

In any case, Thuram argued, it would be better to confront racism directly by going to Russia and playing in front of racist fans.

This is not a bad argument. There’s a historical precedent for it as the American sports historian, Jeffrey Sammons, reminded the NYU audience: At the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico African-American athletes on the US team, after campaigning for a boycott, eventually decided on this strategy, using their time on the medal stand to bring attention to US racism. (BTW, there’s a great BBC documentary covering those events. You can watch it here.)

Wahl, though, changed the subject and it seemed settled for the night.

That is until Elliot got up during question time and brought up Israel.

As is well known, Israel has discriminatory and oppressive state policies towards Palestinians. Yet earlier this year it hosted the UEFA Under 21 Championship, in which the best young European players competed. In the lead-up to the tournament, a group of mainly French-speaking African players (and black French players), led by Frédéric Kanouté (he played for Sevilla, Tottenham and Mali), wrote a letter to UEFA protesting the tournament. Elliot wanted to know from “Professor Thuram” whether he supported the campaign, as well as why it was that yet again it was a case of black footballers providing moral leadership in the game.

Thuram seemed to pause, then responded that UEFA should have insisted that matches be played in both Israel and Palestine.

Some clapped. We were disappointed, but realized soon after that we missed what Thuram had done. He had shown up the absurdity of Israel being a member of UEFA. In what sense is Israel part of Europe? He clearly knew that his proposal to insist that tournament games be played in both Israel and Palestine was impossible, since this would have meant holding European championship games within the Asian Football Confederation, of which Palestine is a member.

And what was the substance of our disappointment? We were waiting for Thuram to tell us what we already knew, to offer a strident condemnation of Israel’s racism. The temptation was to be frustrated by his canny answer. But what right do we have to place a special obligation to combat racism on Thuram? Why should we expect him to provide moral leadership on every issue, when most other prominent players never speak out on any issue at all? One can criticize Thuram, but isn’t it a bit crazy to do so when so many other players are silent?

November 23, 2013

Weekend Music Break 62

10 new music videos from Zimbabwe, Lesotho, Kenya, Mali, Burundi (via Belgium), South Africa and Nigeria (via the US and the UK) to get your weekend started. But first up, from Senegal, Daara J Family have a new video out, directed by Lionel Mandeix and Loïc Hoquet. N’Dongo D and Faada Freddy, from Dakar, still bringing it after all those years:

“THIS VIDEO IS SOOOO AMAZING IT HAS A JAMAICAN VYBE PLUS DANCING N FLAVOR I GOTTA LUV MY NAIJA PPL DEM TUN UP LOUD BUSS TWO BLOODCLAAT BLANK FI DIS!!!” And that was just one of the first YouTube comments under this new Burna Boy jam, ‘Yawa Dey’, directed by Peter Clarence:

Here’s another Nigerian jam, by Omawumi and Remy Kayz:

More Pan-African styling courtesy of Nde Seleke in ‘Pelo Ea Ka’. Lesotho house music as good as it gets:

Kenyan director Wanuri Kahui shot this video for South African rapper Tumi — is this the new Pan-African aesthetic?

Compare the above to what Zimbabwean hip-hop artist Orthodox is doing in Bulawayo…

…or what Nigerian-American Kev is doing in Queens, New York (he is part of the Dutty Artz’ L’Afrique Est Un Pays project — check the EP we shared yesterday):

In Kenya, Muthoni the Drummer Queen has released an unusually dark video:

Meanwhile, in Belgium, Burundi-born (but claiming Rwanda as his original home) Soul T knows his Soul classics; this is a first single off his EP Ife’s Daughter:

And now for something completely else, to end, ‘Ay Hôra’ is a great new tune by Malian singer Sidi Touré and band (throwing a good party too):

November 22, 2013

L’Afrique Est Un Pays

This past October was the Dutty Artz crew’s 6 year anniversary, so we decided to celebrate by releasing a compilation in the form of a series of four free geographically-oriented EPs with accompanying DJ mixes. The final edition has Africa as its loose geographic focus (even though we’ve already dipped into Africa with our What Edward Said EP), and is a collection of songs that I am very proud to share with the world. The other EPs were only available to download for those who signed up for the Dutty Artz mailing list, but in case you missed them, the entire compilation will go on sale in mid-December.

Since Africa is a Country has become an integral outlet for myself, and for African thought in general, I thought it would be good to co-present the EP here, offering it as a gift to Africa is a Country readers. So, for a limited time you can download the L’Afrique Est Un Pays EP by liking the Africa is a Country facebook page!

Dutty Artz is a crew of artists and creators, but we are also very concerned with thinking about and engaging with arts in new ways that challenge dominant social norms and industry standards. So, it makes sense that the presentation of the EPs evoke such ground breaking and intellectually challenging literary giants as Edward Said, Paul Gilroy, and Eduardo Galeano. The literary theme also extends to the fourth EP, taking a deeper connection, as Binyavanga Wainaina opens the album, talking about the first time he met Chinua Achebe (the cover borrows the artwork from the 50th anniversary of Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart).

Kicking off from that framing we land in Queens, New York, where Nigerian-American rapper Kev skillfully depicts life growing up as a “westernized African.” I was introduced to Kev after receiving a tweet from his manager, and instantly thought to include him on the project. The song “Leave Me Alone” resonated for me, especially in the wake of the Afropolitan debate that has arisen in recent years. While these days I tend to shy away from debates about identity politics, I couldn’t help but be drawn to Kev’s claims of identity equality, because he introduces it in such a matter of fact way. A strong voice fighting against dominant ideas of Africa continues to emerge, especially from the fringes of the contemporary global city.

The rest of these songs deal with these same issues of definition and expansion, albeit in more abstract ways. I turn in a track inspired by Janka Nabay’s rallying cry for all Africans to love their own culture, introducing the world to my definition of Bubu Crunk. Fourth in line, my Dutty Artz compatriots introduce a musical experiment aimed at tracing and rearranging the cultural lines that criss-cross the Atlantic. And finally, the French Kudurista Frédéric Galliano is back, with a trusty club banger – primed for the naughtiest part of the night!

To accompany the EP I enlisted Brooklyn’s Black Atlantic Techno specialist Lamin Fofana to help me construct a mix inspired by the theme. The songs he both selected make for a great deep listening experience, good for zoning out while working, philosophizing about global African society, or just riding a bus or a train. It’s permanently available for download so you can take it to whatever occasion you see fit, enjoy!

My Own Private Mangaung

Heard about Mangaung? No, not the site of the 1912 founding of the ANC nor last year’s ANC Conference. The real Mangaung. The prison. Mangaung Prison, run by G4S, is the world’s second largest private prison in the world. G4S is proud of that. They’re not so proud of last month’s allegations, revealed by Ruth Hopkins of the Wits Justice Project, of gross, brutal and widespread torture, forced anti-psychotics and shock therapy, and general anarchy and chaos on the part of the staff.

The nation was ‘shocked’. The world was ‘shocked’. Those who follow prisons, and not only in South Africa, were not surprised, but hopeful that perhaps something might be done. To absolutely no one’s surprise, G4S, already embroiled in fraud and deceit scandals in its United Kingdom operations, denied the charges. In fact, they argued that, to the very very contrary, Mangaung Prison is an “excellent example” of private-public partnership. An investigation was launched by the Government.

On Tuesday, November 5, Correctional Services Minister Sbu Ndebele announced to Parliament that, in South Africa, prison privatization is a failure. The Portfolio Committee on Correctional Services agreed. The Committee was also told that a two-pronged investigation would be released two weeks hence. In other words, three days ago.

Heard about Mangaung? No? Neither has the Committee on Correctional Services, and neither has the country or the world. Instead, the publicly supported ‘private hell’, the Black Hole, that is Mangaung, and has been Mangaung since its 2001 opening as the first private prison on the African continent, a pearl in the NEPAD crown, has dropped into its own black hole … yet again.

And that is a damn shame.

Why are historians suddenly looking at Sweden’s colonial past?

It is, to a surprisingly large extent, a story that’s been going on since the Second World War. Sweden–it is said–is different from the rest of Europe. After all, “The world’s conscience” (as newspapers in the West sometimes describe Sweden in shorthand) had never been properly colonialist.

As the historian Gunlög Fur explains: “Colonialism was defined as control over other territories, and Sweden, it could claim, was a marginal player at most. It was made believable internationally that Sweden was not part of any mechanisms of oppression, and it could avoid being seen as a colonial power. Instead, Sweden saw itself as the moral equivalent of a great power, building up its sympathy with the marginalized and oppressed.”

Gunlög Fur is professor of history at the Linnaeus university in Växjö. Earlier this year, she had a historiographical survey published of how academics have treated Sweden’s relationship to its colonial past. To her, that post-war period was notable for the way Sweden’s colonialism was placed “beyond or outside of the nation,” explained away as not part of the nation’s identity.

The last dissertation on Sweden’s slave trade was written in the 1950s, for example – since then the subject has been considered unimportant, a failed historical period at best. Instead, an image of a benevolent, preternaturally anti-racist “good old Sweden,” spreading its perfect democracy around the world, has lingered and continually defined what it means to be constructed as Swedish, with the possible exception of a select few researchers from the eighties onwards.

But suddenly, in the last few years, that identity may have started to crackle in the public debate. The signs are suddenly everywhere: from the cake that shone a light on its ignorance of offensive imagery, via the revelation that middle-aged white culture editors are so painfully attached to their racist Tintin comics they will turn any analysis of them into a censorship debate, to the exposure of the very direct, structurally and personally impactful racism present in officially-condoned racial profiling and ethnicity-based police registration. In all of these discussions, Sweden’s colonial history has suddenly started to be discussed everywhere.

And, as if by startling coincidence, 2013 seems to be a year in which academic research has really started to examine Sweden’s colonial past again. Gunlög Fur’s overview was published in a major collection on Scandinavian colonialism that came out in February. In May, Uppsala University historian Fredrik Thomasson published a summary of his ongoing project about the justice system on the Swedish slave-trade colony of St. Barthelémy in a history teacher’s review, which generated enough interest to become a news item in major swedish media. And in September, historian David Nilsson* at the KTH Royal Institute of Technology published a long-form report on Sweden’s participation in the infamous Africa-dividing Berlin conference, which was followed up by a seminar on Sweden’s participation in the scramble for Africa. The timing is fortuitous: for a debate that is sometimes laughably mired in subjective judgements of the I’m-not-a-racist kind, this kind of evidence-laden chronicling is reinvigorating.

And it’s certainly notable how all of the researchers are covering ground that has essentially been abandoned for half a century – or never been touched at all. Gunlög Fur not only looks at the period after the war, but also compares and contrast sources from the preceding period – and uncovers an attitude that, in European terms, is rather more conventional: a nationalist pride, a feeling that the expansion of the nation’s territories was “natural”. Pride, in the very least, when it comes to some of the projects, like the North American colony of New Sweden.

For Fredrik Thomasson, his research taps into an archive that no historian had yet to source: The section about the courts on St. Barthelémy in the French Archives Nationales d’Outre Mer in Aix-en-Provence. (France both preceded and succeeded Sweden as the island’s colonial overlord.) Spanning over a time of several years, he and his assistants have managed to recover what amounts to intriguing insight from sometimes badly-damaged material, including a whole deal about the social life of the island, not least that of the slave population, and that of the highly segregated and legally discriminated “free blacks”.

“I’ve been able to access a great deal of both civil cases involving slaves and criminal cases,” says Thomasson. “I don’t see any real difference between the way slaves were treated in the Swedish colony compared to other colonies. The legal system was not the one used in Sweden, but rather similar to a common law system: it was ‘make it up as you go along’, reactive to the life on the island.”

Slaves were subjected to all the horrors associated with the practice: complete control over their lives, harsh physical punishment meted out by owners, and little legal protection. The few owners who over-flogged their slaves were merely forced to pass them on onto another master.

David Nilsson, too, has looked into correspondence and reports that have almost never been examined before, to try to get at the political motivation behind Sweden’s participation in the Berlin conference. While international sources mention Sweden’s presence in the proceedings, it turns up nowhere in Swedish history writing, and certainly is not mentioned when the Berlin Conference is brought up in schools and undergraduate courses.

Turns out Sweden was a keen participant in the conference, albeit as a marginal player on the outskirts of the negotiations between the great powers. “Sweden’s motivation for being part of the conference were fourfold,” says David Nilsson. “First, it was afraid of being left out, it wanted to show itself as having a stake in the future. Secondly, it wanted to ensure its trade fleet, the second largest in the world, would have access to especially the Congo free state. Third, it subscribed to the idea of spreading civilization, which is explicitly mentioned in the media at the time. And fourth, it was part of King Oscar’s desire for a closer relationship with Germany, with Sweden’s participation adding legitimacy to the proceedings as well as lending Bismarck a hand in his newfound colonial ambitions.”

None of these motivations, says David Nilsson, make Sweden unique. “It is true that Swedish interests in Africa were only marginal at the time, and Sweden remained a minor player. But qualitatively I see no distinct line between Sweden and other countries,” he says. “Sweden went to Berlin as a peer among nations, accepted and condoned the proceedings. It was a political justification of a social process that had already begun as Swedish officers and missionaries were already taking part in the colonization of Africa.”

This categorisation, of Sweden being very similar to other nations at the time, is a repeated theme that comes up in all of the conversations with the historians. Sweden is not an “exceptional” country, historically speaking; rather, it is part of the same system as all other countries.

“I think to an extent, focusing on Sweden alone is wrong,” says Fredrik Thomasson, “It supports an outdated model based on the Swedish nation state.” Instead, like many other historians in recent years, he supports models that look at history from a global, transnational perspective. Here, Sweden is no more or less important than any other nation state, but participates in global processes like colonization and the global slave trade as part of a bigger system. One intriguing manifestation of this, for example, is how Sweden’s iron industry was a pivotal participant in the material system of the slave trade, providing both shackles and the majority of the specifically forged voyage iron bars that were used to trade for slaves in Calabar and Bonny (in what is now Nigeria). Examining such connections are practically impossible when looking at just one country.

In an insular academic world, such theory shifts may explain in part the fact that historians have, relatively simultaneously, started to take on Sweden’s colonial history. And there’s also a frustration with the way the public debate sometimes seems painfully short on facts: “We tend to simplify our image of ourselves,” says David Nilsson. “We need to understand that our history is complex. If we had that understanding, we’d have a whole different self-image.” Fredrik Thomasson, likewise, calls the lack of knowledge an “amnesia” and criticizes the lack of basic research. There’s a palpable sense of the good old Swedish self-image being a significant motivator.

But of course, there’s also a factor of a changing economic, ideological and structural landscape that creates opportunities for this kind of research to take place. The economic crisis of the 90s or the changing cultural makeup of Swedish society are common touching points. David Nilsson, who has a background in the development aid community, points to the adoption in 2003 of a new government policy on global co-operation. This policy could be seen as a manifestation of the gradual shift: from Sweden’s international image of being driven by altruistic motives, to just one among the many nations focusing on trade and global public goods such as security and climate change. This, he speculates, has opened up a space for Sweden to tackle its own history relative to Africa and the colonial past as well. Gunlög Für points to the international community’s pressure to recognize Sweden’s treatment of its indigenous Sami population as colonial as an important factor.

Fredrik Thomasson is rather more skeptical of the stated motives: He believes Sweden is merely following a changing sense in what’s considered “good” and radical. “I think a lot of the Zeitgeist is a desire to be part of the post-colonial wound,” he says. “Unless you have colonial guilt, you’re not allowed to play with the big boys.”

And perhaps, structurally, that puncturing of the self-image is not so complete after all. Rather than radically re-engineering its relationships internationally, perhaps it is a mere cosmetic paint to appear good again, good by today’s standards. And it’s worth to contemplate whether perhaps Gunlög Fur is right, and admitting guilt in this public manner may actually strengthen Sweden’s already powerful position: “In this time of uncertainty about the nation and the role of the state, it’s important where a country positions itself. To be a colonizer is something negative – yet at the same time, it’s allowing yourself agency. Perhaps it strengthens you to see your past a colonizer, showing that you have power and a capacity to influence the world.”

* The top image is of David Nilsson (at the Ethnographic Museum in Stockholm) by Justine Balagade.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers