Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 405

May 26, 2014

The Fader goes to Cape Town

So I’ve been following the Sprite Obey You Collective video series on The Fader website. They have been profiling some young South Africans doing great things. I liked the idea. I saw the Okmaloomkat clip. I liked the one about Lenny Mogoba (a female basketball player from Wits) one. With a lot of things happening on the internet and my life (which revolves around the internet anyway), and me being the scatterbrain I am, I somehow lost track of the series.

A friend of mine emailed me a link to the most recent episode in the series about the Cape Town music scene:

As you can see, the first few minutes of the series reminded me that electronic music has a strong presence in the Cape Town music scene and that hip hop is not just about rapping and that the beat scene in Cape Town is at a great place right now. Coincidentally, I am currently (listening to) Christian Tiger School and PHFat. It also reminded me that gone are the days when hip hop in Cape Town was just a black and coloured thing (yes, some coloured and blacks view themselves as different races in South Africa).

There’s a lot of white participation in the genre now. Which is a great thing. Marc of Oh! Dark Arrow, Das Kapital, the Christian Tiger School duo (all white) appear in the first minute of the video saying great things about how the great place the Cape Town music scene is in. They are followed by Cape Town’s hip hop golden boy, Youngsta. “Hip hop started in Cape Town. First place it started was here–Mitchells Plain. We almost 20 years later, and now it’s being started again, by this generation now, the Y? Generation [his crew],” he states in his trademark bravado. I agree with him. South African hip hop pioneering crews Black Noise and Prophets of the City are from here. And the momentum at which Cape Town hip hop is growing in is impressive and quite fulfilling. Cape Town hip hop is very exciting right now.

Youngsta continues: “When we rap, we not gonna rap the same thing as an African from the townships ’cause he’s growing up in a different place. We rap about what we know – our lifestyle, the way we live. And they rap about what they do. Cape Town is starting to finally take pride in that.” Wait. What is an African? I’m discerning a sense of “them” and “us” – them being the “’Africans’ in the townships” – the blacks I guess. Yes, I agree that coloureds and blacks in Cape Town live completely different lives and that is reflected in the music, but I didn’t know that coloureds were not Africans. I’m confused. What is an African really?

Seeing that the video was less than 5 minutes long, I was expecting to see Ill Skillz or Driemanskap or Khanyi in the following 30 seconds representing, umm, African hip hop. Soon after them, I was expecting to see Jaak or Blikmenstraal or Jean Pierre or Jitsvinger repping Afrikaaps but alas I saw DJ Leechi, Haezer, and oh wait, in the midst of the performance shots which were generally white-dominated, I saw E-Jay (finally a black rapper, even though he’s not Capetonian but Angolan). I was a bit relieved but wait, just as I expected his soliloquy on the issue, a Push Push (female DJ/ rapper) who is–yes you guessed it right–white and appeared and spoke about how hip hop is doing great in Cape Town now. Basically.

“We are such a diverse country in terms of people and it’s so clear in the music,” says Das Kapital in the concluding minutes of the short clip. It may be clear in the music as he says but this short doccie falls short in capturing that. According to what’s shown here, EDM (electronic dance music)–which is white-dominated–is the sound in Cape Town. What about spaza? What about Afrikaans rap?

The video was dominted by “white” shows – with a lot of electrocentric music and flashy strobe lights. It is blatantly biased and saddens me deeply as a lover of Cape Town hip hop, who has equal amounts of respect for Driemanskap, Youngsta, Ill Skillz, Christian Tiger School, and PHFat, just to mention a few. Total fail.

The complicated politics of conversion in Northern Nigeria

In Boko Haram’s video released earlier this month, a member of the group (presumed to be Abubakar Shekau, the group’s leader and spokesperson) claimed that the kidnapped girls in northeastern Nigeria, many of them born to Christian families, have been “liberated” by conversion to Islam. Predictably, Christian media outlets in the United States and “anti-jihadi” vigilantes online all rushed to condemn this. The Christian Association of Nigeria described the conversion as evidence of war against Christians and Christianity. The secular western media reported it but reserved comment, following up with stories of the hatred of non-Muslims among Boko Haram’s leadership. Though the group has targeted Christians in violent acts, we should not misread forced conversion as a strategy exclusive to Islamist terrorism. The history of conversion in Northern Nigeria, as in many countries at many points in history, shows that coercing or controlling conversion has long been a strategy of political power. (A good comparison comes from India, where evidence shows competitive and coerced conversions to Christianity and Hinduism).

In Northern Nigeria, 19th century Christian missionary conversion campaigns upped the ante in the struggle for converts. Jihads swept the region in the early 19th century in an effort to reform lapsed Muslims, rather than to convert nonbelievers, but the competition for converts escalated when, during the 19th century European scramble for colonies in Africa, Christian missionaries from many European countries, the United States, and Canada sought to carve out spheres of denominational influence in the region. Even before the British formally conquered Northern Nigeria, Christian missionaries from England and Canada sought desperately to reach Kano from Lagos. German missionary Karl Kumm believed that the non-Muslims of the Sudan (which would have included the people in Chibok a century ago) should be converted to Christianity to serve as bulwarks against expanding Islam. (The American Church of the Brethren, with a more humanitarian agenda, opened a mission station in Chibok in 1941. The links between Northern Nigerian and American Christians remain: on May 7, 2014, the Chibok church asked its former parent church in Elgin, Illinois, to pray for “the safety of all children,” Muslim and Christian.)

Missionaries’ presence in the region added layers of complication to the complex political relationship between Muslim and British authorities. Latter day defenders of Christendom would doubtless be surprised to learn the extent to which British rule in Northern Nigeria was predicated on cooperation with local Muslim elites, who collected taxes and administered sharia courts. Elsewhere in Africa, the British generally embraced Christian missions as handmaidens, but, in Muslim Africa, the British tried unsuccessfully to block their evangelism and occasionally went so far as to encourage the mistreatment of Christian converts in Muslim areas, rather than risk unsettling the status quo.

In 1926, for example, a Muslim teacher of boko (which then had a range of meanings that have since been forgotten, notably by the US National Counterterrorism Center), converted to Christianity. This worried his British boss, who brought the recent Christian before the Kano emir to assess the “truth” of his conversion. The emir did not force the man to recant, but, over the ensuing decades, Western-educated Christian Northern Nigerians were frequently subjected to intense pressure from British and Muslim authorities to become Muslims in exchange for jobs in government. In certain contexts, religious conversion was an expression of political loyalty and a path to social advancement.

Not surprisingly, the complicated politics of conversion in Northern Nigeria often unfolded in Western-oriented schools, which Muslim clerics perceived as a tool of the missionaries used to seduce Muslim youths. Clerics pressured political leaders to limit enrollment in Christian schools by stipulating minimum ages for children. Some Christian Nigerians, too, reacted against the missionary legacy in education. Tai Solarin, an educationalist who founded the Sunflower School in a predominantly Christian area of southwest Nigeria, for example, regularly fought religious crusades undertaken by students, mostly Pentecostal. The efforts to separate conversion from education are ongoing and contested.

Forced, coerced, incentivized—religious identification in Nigeria has only sometimes been about free will, as Westerners aghast at conversion by kidnapping might assume. Indeed, many missionaries were the enemies of free will. In 1958, two years before Nigerian independence, a British-appointed commission studied minority affairs in the North, finding that Christians numbered 550,000, Muslims 11 million, and “pagans” or “animists” nearly 4.5 million. The commission worried about the missionary tendencies in both world religions: “Islam is a dogmatic and prosleytising religion—but not the only one. There are intolerant people on both sides of this controversy and there will always be instances of intolerant behavior. This is a matter that only legislation can point the way.” No laws against unwanted proselytism ever came. Islam and Christianity continue to struggle it out in Nigeria—with increasing levels of violence on both sides, albeit more on the majority Muslim side in the North, and the total disappearance of those professing to be practitioners of indigenous religions.

No modern state in Nigeria—the colonial or postcolonial—has dealt effectively with minorities, missionaries, or religious dissent. We must now place our hopes in political and military authorities, not religious ones, to find the missing children and disarm Boko Haram, whose violence (and counter-attacks by government forces) has led to thousands of civilian deaths since its designation by the U.S. government as a foreign terrorist organization in 2012 and the Nigerian government’s declaration of the state emergency in 2013. Boko Haram is a product of fear of government’s violence and intimidation, lingering from contests over conversion, religion and political identity in the past and casting doubt over the future. Collective organization to pressure the Nigerian government is heartening, but moral appeals inflamed by the media and religious partisans hark back to the colonialist mentality of saving souls in Africa and fall into the trap set by the anti-colonial salvationism of Boko Haram. Uninformed and unscrupulous salvationism should not obscure the tangled history of Muslim and Christian competition in Northern Nigeria.

May 24, 2014

Kickin’ It With Christian Tiger School

I arrive in Braamfontein twenty minutes early, at 6pm, for a meeting with Sebastiano Zenasi (or Seb), Luc Vermeer, and their manager Aaron Peters. It’s the night of their album launch, their second since 2012’s Third Floor landed them in the electronic music spotlight and enabled them to get book at nearly every major music festival in South Africa.

Sebastian is currently on the decks warming up the dancefloor at Kitcheners, a much-loved venue located in the heart of the city. Later, his partner Luc will let loose a well-executed set featuring the latest in gritty rap music–from Pusha T and Kendrick Lamar; to Action Bronson and Roc Marciano; and a bit of Drake for balance.

Seb and Luc are Christian Tiger School, a Cape Town-based production duo whose sound used to exist explicitly within the confines of J.Dilla’s school of beatmaking. The quest to explore their full range means that the Christian Tiger School ‘sound’ (hear the Questlove-endorsed Carlton Banks) is slowly making its way away from that territory. On their latest offering Chrome Tapes, they sway between hard-hitting hip-hop drums, snake past EDM territory, and give a wink at jazz’s–and other genres’–direction.

Chrome Tapes is Christian Tiger School on an upward trajectory. They present new ideas, or new ways of interpreting configurations and arrangements which have already been explored. The music is immersive; their drums are more layered; their sets more considered.

Our interview doesn’t happen right away. When we do talk the next day, Seb tells me that he’s been listening to a lot of house. It bleeds through to the music. Luc, in contrast, is extremely selective about the type of house music he listens to. “[I listened to] like, four house songs regularly throughout the past year” he states.

Both have learnt a lot over the two year cycle since Third Floor got released. Seb has a side project called Yes In French and collaborates with Nic van Reenen as part of his (Nic’s) live ensemble, Fever Trails. Luc’s always onto next-level beatmaking as Desert Head.

This Johannesburg show will be their last in South Africa for at least two weeks. They flew themselves to New York last year to play a couple of shows and see if anything might come from interacting with people in that scene. Through those moderately-sized gigs, they managed to get booked to perform at Okayafrica’s SXSW showcase this year alongside fellow Capetonian Petit Noir. They’ll fly out on Tuesday, play some shows, and head towards the West Coast to explore the LA beat scene as well as see if more fruitful exchanges occur. Aaron mentions Brainfeeder, possibly.

The group has recently inked a management deal with Black Major, a Cape Town-based agency. By association, they’re in the same league as John Wizards and Fantasma (Spoek Mathambo’s new project). In short, things are looking pretty fucking good for Luc and Seb!

Check out this video in which Christian Tiger School speak about how they plan to release this album and how they tackle late night slots at festivals. It’s an Africa is a Country TV collaboration between myself and Leila Dougan.

*Christian Tiger School have a crowdfunding project to help them get to Primavera Festival in Spain. You can lend your support here.

May 23, 2014

Nobel Laureate Wole Soyinka has opinions about social media (he hates them all)

‘… Let me take this opportunity to announce yet again that I do not tweet, blog or whatever goes on in this increasingly promiscuous medium. I do not run a Facebook, even though I am aware that one or two serious-minded individuals/groups have instituted some such forum on their own, for the purpose of disseminating factual information on my activities. I neither contribute to, nor comment on the contents of their calendar … To speak generally, Internet abuse is getting to be a universal plague, one that goes beyond personal embarrassment and umbrage. I strongly recommend collective, professional action to protect the integrity of the medium, and save it from becoming a mere vomitorium for unprincipled scallywags with, or even with no particular axe to grind.’

A new film is all about DSK’s naked belly; Nafissatou Diallo as minor prop

Three years ago, New York was gripped by the legal battle between then-IMF chief Dominique Strauss-Kahn and the woman who accused him of rape—she turned out to be the maid, who had come in to clean his room at the exclusive Sofitel Hotel. Africa is a Country wrote a ton of analysis on the case and its meanings (see here and here), countering lazy, and often racist reportage about DSK’s accuser—later identified as Nafissatou Diallo, an immigrant and asylum seeker from Guinea.

Now there’s a movie version, “Welcome to New York” directed by Abel Ferrara: Gerard Depardieu is cast in the role of the rutting, out-of-control global financier; the character is named George Devereaux in order to avoid a defamation lawsuit; although the film is explicitly “billed as a piece of fiction and comes with a legal disclaimer,” DSK has already set a defamation suit in motion, instructing lawyers to sue movie makers).

Here’s the trailer:

Critics have been underwhelmed by the film, praising Depardieu’s performance, but finding fault with Ferrara’s direction. The Independent calls the film a “gritty and grubby tale,” while Indie Wire described it as “laughable and grotesque to the extreme”. Variety called the movie “a bluntly powerful provocation that begins as a kind of tabloid melodrama and gradually evolves into a fraught study of addiction, narcissism and the lava flow of capitalist privilege”; and The Guardian’s Xan Brookes describes Devereaux as “a brutish sex addict and master of the universe” who is shown in opening scenes “slapping buttocks with abandon and climaxing like a tomcat,” and operating “a revolving door of prostitutes”; although there must be considerable pressures from his Big-Time job squeezing poor countries, he still finds “time to force himself on any passing female, be it a Guinean maid or a young journalist sent to interview him.”

Missing in the action: Nafissatous Diallo, who is simply a prop in the development of the subjectivity of the global financier and his Lady Macbeth—George Devereaux’s wife, who is only referred to as “Simone” (played by Jacqueline Bisset).

After the somewhat cheesy-yet-gritty opening group sex scenes intended to leave us with no doubt about Devereaux’s reprehensible character, the film moves on to serious business, taking on the pace of a crime-thriller: there’s the shrewd, calculating NYPD, which lures him—using the pretext of returning his lost Blackberry to him (how’s that for American service!?)—out of his first class seat on a plane bound for France and back to the airport in order to arrest him. There are also scenes that clearly champion the working stiff policeman as hero of justice, unfazed by the awesomeness of the global financier in front of him. Naked, and under the egalitarian hand of the American process of booking a prisoner, Devereaux is a drooping, decaying, fat body.

In fact, Depardieu’s naked fatness is the most praised element in all the film reviews; somehow, his heaving, unapologetic fat belly, drooping flesh forcing itself on a variety of women – including the hotel maid – is lauded as the best part of the acting. And in the scene where he is being strip searched inside the US prison, Brookes finds that “Ferrara’s camera has [Depardieu] literally exposed, like an old bull being weighed and examined ahead of the slaughter.” Xan Brooks praises Depardieu’s “mighty performance,” calling it “the best he’s been in years.” Maybe all this praise of Depardieu’s exposed body has to do with American/Western aversion to displaying the evidence of over-indulgence and excess on the body; while consumer hedonism is acceptable and in fact encouraged (think $5000 -$10,000 bags, shoes, clothes and 500,000 cars), excessive food consumption and its inevitable results on the body are meant to be erased, denied, or at least graciously hidden. Depardieu’s exposed, late middle age body, weeping from excessive consumption, thus becomes translated as a significant part of his acting methodology. It is also a vehicle for displaying the contradictions of late capitalism: there’s our desire for and praise of unchecked power on the one hand, and on the other, there’s our distaste for the slovenliness of a man who cannot contain or control his appetites. That excessive body has to be put on display in order to be examined and shamed. No wonder critics are blinded by Depardieu’s body of work.

But after all that shaming body exposure, the plot takes a twist, as did the real story of DSK and Diallo. American justice gets put in its working class place by Euro-oligarchy. Enter Devereaux’s rich wife (Jacqueline Bisset), who comes from generations of wealth. After than, we get to see some truly crazy scenes beteween Devereaux and his wife. She’s got ambitions for our jowlsey Romeo, and now he’s fucked them all up: “He’s destroyed everything I’ve worked for,” she rages like the Lady Macbeth figure on whom her character is built. Anyway, we know what happens. Rutting Romeo gets off, but loses his chances at a political career. Exit Lady Macbeth. And what of Nafissatous Diallo? We’ve no idea.

Hilariously, Cannes’ board felt that this film was too weird for its official spaces; so “Welcome to New York” was privately screened on the sidelines of the Cannes film festival over the past weekend; Geoffrey McNabb at the Independent put the best spin on it:

Rejected from the festival’s competition, the movie screened at a special gathering on the beach adjacent to the official event, projected off a laptop streaming the movie from one of the many video-on-demand platforms where it’s now available in France. Nearby, the thumping beats of beach parties constantly provided an unintentional soundtrack, but the invasive elements actually enhanced the mood. After all, this is a movie in which the seediness constantly threatens to burst off the screen.

Heathrow Airport maps the world, and it still belongs to Britain

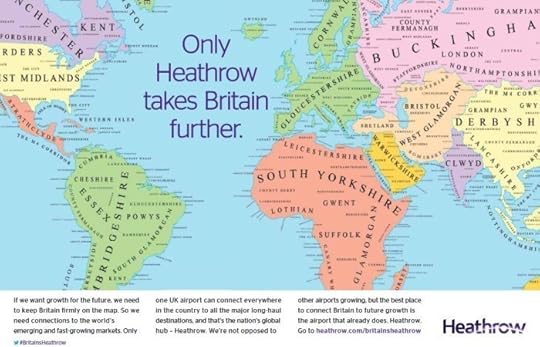

I was sitting in the tube recently and browsing through one of those free morning papers that no one really reads when I stumbled on a new Heathrow Airport ad with the legend: “Only Heathrow takes Britain further.” The ad depicted a Eurocentric world map lacking national borders or state names. Not only is Britain placed right at the centre (how else?), but Britain seems to have swallowed the entire world and transformed these countries into its own little provinces: the whole of Africa has become part of South Yorkshire, Leicestershire and Glamorgan; South America is, amongst other things, divided between Cambridgeshire and Essex; West Asia (a.ka.a the Middle East) is annexed by Warwickshire; continental Europe has gone over to Gloucestershire. The entire world had literally transformed to become a British settlement. Kind of like…um, colonialism never ended.

In the throwaway pages of newspaper that a fellow passenger left behind, Heathrow Airport invites Britons to imagine a complex, non-too-happy past as the happy, simple present; here, in the advert’s world, Britain’s colonial hangover is swapped for an imagined past where Britain never lost its Empire to anti-colonial movements, Instead, it further extends its iron grip over non-Brits, including white Europeans (o, beware). A nightmare vision for many, but it’s apparently an acceptable enough view that Heathrow Airport’s marketing people didn’t think twice before plastering it all over London’s public transport system for millions of postcolonial peoples on their daily commutes to consume.

The image above is of the map alone. Here’s the full ad (click on it to enlarge it):

This whole sham was, however, not Heathrow’s first atrocious attempt to map the world and provide us with a possible vision for the future. Two years ago, Heathrow Airport decorated the London Underground with a similar colourful ad campaign claiming, “Only Heathrow brings growth to our doorstep”. The ad depicted Britain surrounded by a world divided into ‘customers’ and ‘opportunity’. The division line was both economic and racial. While first world states—in other words, majority white states—were labelled as customers, while the remaining world—all postcolonial nations—were plastered with a big fat OPPORTUNITY stretching from Africa across to Southeast Asia, and all the way to Central America.

Since the launch of their ad campaign in 2012, little outrage was to be heard or seen about the company’s use of overt neo-colonial expressions to promote itself. The sparse online criticism that emerged didn’t go beyond personal blog posts and Facebook comments, as if the campaign failed to reach the wider public. Heathrow Airport wasn’t impressed at all. Clearly, they thought so little of the voices protesting their campaign that they took their neoliberal and neo-colonial ambitions a step further, as I saw in their newest commercial on the discarded paper.

In this new ad, Heathrow Airport successfully transforms territories labelled as ‘opportunities’ and ‘consumers’ to become full colonial subjects who are available for Brits to access and put to labour at all times. It tells daydreaming Britons, “The World’s emerging markets are growing over 8%”: in other words, grab it while it grows and grab it while you can. Sounds strangely familiar, no? When the first British colonisers left their southern English ports to steal resources, people and land in the so-called ‘New World’, they must have been driven by similar rhetoric: grab it while you can, grab it before the Spanish and Portuguese do. Today, the competition for Britain in Africa is China; but the interpretation, however, remains the very same.

We all know that Britain continues to have a hard time coming to terms with the economic and political losses it endured with the fall of its Empire. Over the decades, the small-island state tried in vain to return to its so-called past glory through different cultural, economical and political means. From the British Council to the DFID to the Commonwealth or the EU, each of these seemingly benign organisations serve as platforms for Britain to advance its interests and influence, as well as in attempting to regain a global status it has long lost but continues to yearn for.

When Heathrow Airport engineers its advertising strategy using a familiar refrain (we can regain our former glory!), it not only amounts to an endorsement of Britain’s colonial past, but also its neoliberal present. It celebrates a hegemonic project which cannot be divorced from globalisation and imperialism and the diverse ills it produces. Mapping the world for commercial reasons mimics neo-colonial power-relations that continue to affect the lives of millions people, including people in places like South Africa, Ghana, Nigeria, Rwanda or Egypt where British business interests and investments run high and often at the expenses of local populations.

With its ad campaign, Heathrow Airport attempts to return Britain to an age of global relevance. The PR team behind this advertisement campaign clearly didn’t include anyone politically or historically astute, and I’d assume no person of colour either. It simply positions itself as the new point of departure for presumably white Britons who will board countless planes, on their way to exploit the same people promised lands of the Global South.

May 22, 2014

Toto’s Africa–The Disco Edition

Came across this nice little disco edit of Toto’s “Africa.” Since we have a running series going, thought it would be nice to add it to the bunch.

So deeejay! Take us awaaaay to Aaaaaafrica!

Afrobeat, Brazilian Style

The following is a guest post from Wolfram Lange, a Brazilian music aficionado based in Rio de Janeiro. A few months ago Sean and I were discussing the upsurge in interest in (Fela Kuti’s) afrobeat music in Brazil. When doing a little research for a post, I came across a great comprehensive mix on Wolfram’s Soundgoods blog. So, I thought it would be great to just have him expand on that work here (Boima Tucker):

In the midst of the global youth counter-cultural rebellion of the late 1960′s, Brazilian musicians looked to the U.S. and Europe for inspiration while living under a pro-West military dictatorship. They merged rock, jazz, and soul music with their own African-influenced popular musics to create a rebellious and internationally celebrated sound. However, what in hindsight may seem like an obvious connection at the time, engagement with contemporary African artists such as Fela Kuti was limited.

Yet as common knowledge goes, there are always exceptions. In the 1970′s Gilberto Gil and in the 1990′s Nação Zumbi both took inspiration from afrobeat. However perhaps the most surprising example of Brazilian engagement with the sound predates Fela himself! In 1957, Orquestra Afro-Brasileiro released the song “Liberdade,” which has amazing similarities with Fela’s “Shenshema.” Their whole album “Obaluaye!” is a surprising mixture of jazzy arrangements and African rhythms that by that time was very innovative as African percussion was considered to be “barbaric” (piano and saxophone were “civilized” instruments.) Although, the song of Orquestra Afro-Brasileiro is missing the typical drum beat of Tony Allen, it has more African percussion than is common to Afro-Brazilian music styles such as afoxé, jongo, maracatú, samba, etc.

Fast forward to the 21st century [and an African consciousness growing alongside the many contemporary social movements] and the afrobeat resurgence popping around the world has reached Brazil. Now, well-known artists like MPB singer Vanessa da Mata, rapper Criolo, or Céu use elements from afrobeat in their music, as well as many of the less internationally known Brazilian groups and artists. With Bixiga 70 and the Abayomy Afrobeat Orchestra Brazil developing full afrobeat bands, at least two groups have dedicated themselves to play afrobeat at full power.

Check out the following mix for a full taste of the Brazilian take on the sound, and read up on each artist in the track by track breakdown below:

(1) André Abujamra – Origem — André Abujamra is multi-instrumentalist, singer, composer and actor. In the 80′s he founded the experimental Pop Rock band Os Mulheres Negras and later played with Karnak. Despite of his solo projects he composes and arranges TV, movie and theater soundtracks. His music is always a mixture of different styles, which can be heard in this track also containing elements of Balkan and Irish popular musics.

(2) BNegão & Os Seletores De Frequência – Bass Do Tambô — Bernardo Santos is famous after he became part of Planet Hemp, one of the pioneering Brazilian rap bands. In 2001 he left Planet Hemp to start his solo project with the Seletores de Frequência. Fusing rap, hardcore, dub and funk in his music, the lyrics of BNegão add a social criticism reminiscent of afrobeat originator Fela Kuti. In 2008 they launched their second Album Sintoniza Lá.

(3) A Roda – 26 — This band from Pernambuco state was one of the first ones to fuse afrobeat with musical influences of Northeastern Brazil on their album La Estructura from 2010.

(4) Afroelectro – Padinho — Afroelectro creates its sonorous identity by revisiting the African continent through direct contact with musicians from there, and from living in the big metropolis of São Paulo where music from Brazil and the rest of the world clashes. Brazilian culture is mostly found in the lyrics and chants as Capoeira, Candomblé and other traditional elements are put into the mix.

(5) Abayomy Afrobeat Orquestra – Eru — The Abayomy Afrobeat Orquestra was founded especially for Fela Kuti day in Rio in 2011. Abayomy means “happy meeting” in Yoruba, and the first meeting was obviously so happy that the band members decided to continue with the project. They include a Brazilian geniality with bright musical sounds, combined with the driving strength and hypnotic grooves of afrobeat. Apart from their own compositions rooted in Afro-Brazilian tradition, they play cover versions of afrobeat classics and reinterpretations of Brazilian songs.

(6) Bixiga 70 – Tema Di Malaika — The name of of this group from São Paulo originates from the district that has been cradle of Samba in this city and the street number where their studio is. They also reference the name of Fela Kuti’s band with the 70 added at the end. In 2013 they released their second self-titled album.

(7) Rodrigo Campos – Sou de Salvador — Some of the most talented musicians from São Paulo, such as Kiko Dinucci, M. Takara, and Thiago França play on Rodrigo Campos’ Bahia Fantástica album. With “Sou de Salvador”, he shows a rather Bahian approach to afrobeat.

(8) Lucas Santtana – Músico — Since his first album in 2000, Lucas Santtana has been inventing new fusions and mixtures of Brazilian music with different music styles and sounds. Here he hops on the afrobeat revival train with a song that features orchestral strings and his individual guitar style.

(9) Pipo Pegoraro – Sofia — On a trajectory to construct different views on music, from the interpretation side to recording, Pipo Pegoraro comes up with an afrobeat influenced tune on his second solo album.

(10) Tonho Crocco – Abre-Alas (O Carro Destemido) — Tonho Crocco from Porto Alegre in Southern Brazil shows off his soulful vocals by referencing the colorful opening chorus of the samba schools on the first song off his Teto Solar EP.

(11) Rabujah – O Que Meu Samba Tem — This song contains a more funk and rock flavor which combines perfectly with an afrobeat attitude and Rabujah’s epic timbre.

(12) André Sampaio & Os Afro Mandinga – Bumaye — André Sampaio is as talented guitar player from one of Brazil’s best reggae bands, Ponto de Equlíbrio. On his solo project he shows West African influences culled from his research on the music, as well as from his trips to Senegal, Mali, and Burkina Faso, and his collaborations with artists from there.

(13) Anelis – Sonhando — Normally existing between rap, downtempo and Brazilian influences, Anelis samples Fela Kuti’s “Mr. Grammarticalogylisationalism Is the Boss” on this song by Karina Buhr .

* Wolfram and Afro-Brazilian electronic music luminary Maga Bo are working together to launch a record label specializing in Brazilian digital roots music called Kafundó Records. Brooklyn-based label Dutty Artz, will be working with them to present the first collection of songs out this June 10th.

Don’t believe the media hype about striking mine workers in South Africa

The platinum strike led by new trade union Association of Mining and Construction Workers Union (AMCU), is now over four months long, making it the longest strike in the history of South Africa. The majority of the country’s English language newspapers depict the strike as a result of the greedy and unethical leadership of AMCU who have placed the country’s economy in jeopardy through lying to the miners about the viability of their wage demand of R12,500 or US$1,250. But frankly this is bullshit: the strike is a direct result of the state massacre of workers at Marikana and a mining industry which still maintains the same colonial structure of the industry. This interview was conducted with a worker-leader from Marikana, who was shot during the massacre, such voices are not found in the South African media and as you can see, the workers know perfectly well what they are doing.

Could you give some background to the ongoing strike, and explain the factors that led to the continuing mass action?

The undermining by employers, by not coming to (fulfilling) their offer that the workers in 2012 died for. Impala, Anglo and Lonmin, the bosses of those three companies don’t want to pay what they promised the workers who passed away in 2012. They undermine the deals they committed to, and that’s why we said, ‘no, we want to go to strike now’ – because since 2012 till now, there has been no money.

I think it’s important to point out the demand comes from the workers from 2012 rather than being from AMCU – this is a 2012 demand.

Exactly.

So, we are now three months into the strike. From what I’ve heard, the conditions for the workers are quite bad right now; it’s not about the money and people are getting quite hungry and desperate. Are people still fighting? Are they ready to carry on with this?

If you recall what happened in 2012, [the strike] was organised by the workers without any organisation. Then the strike turned violent, and [some] people were not conducting themselves in a [humane] manner.. So workers have now decided to join this union, AMCU. They think that within AMCU, the government and the company will respond positively because now they are more organised and within their correct structures – which [the companies were asking for]. Workers behaved very well; no one has been killed. But it’s those elements, whereby workers are provoked by the police or Lonmin, [and the workers get] uncontrollable because [the companies] are labelling us, saying that we have done this and that, which we haven’t done.

On the other side of hunger and everything, there’s no such hunger to workers. Workers are never going to be hungry because, as they are away from their own rural areas, as they work in mines, they take their money back home to buy cattle [and] sheep, and they are farmers. They’ve got their own money; they cultivated their own land, which means they do have their own reserves. The company [can] call about their reserves, but even [the companies] themselves, they have reserves. So it’s not a matter of food. But they are saying that our salaries are being affected by R 5000 or R 4 000, [and] that we have not eaten in the past three months, but they are talking about [losing] billions. It is something that is new to us. We never knew that we make that much when we go underground – that’s why we cannot turn back on our demand of R 12 500.

And, two, if anyonesays that workers are suffering – it’s not [only] about workers because there are billions, which means the whole nation is suffering. This matter is a matter of public interest. It does not concern the workers in mining alone.

So the question that follows is, how does it feel, knowing that you and your comrades have stopped billions of rands for the bosses? Do you think they’re feeling it now?

The other side we never experienced, but we have them by the balls. What’s happened, you can see, is I’m getting fitter now because I cannot go underground. I’m becoming healthier. These people have done this to our own forefathers, whereby they were enslaving our forefathers. Now we can go and change our minds now because that total of R 500 is nothing. Maybe we decide to demand R 15 000, because what we are now demanding is nothing, it’s peanuts. We will ask for R 15 000 if they just continue behaving like this.

How have the police been behaving in the strike? Have they been targeting comrades, have they been harassing people? Do you feel that the police are trying to break the strike up? I heard about what happened to some comrades at Amplats who got arrested.

When we’re talking about police, we’re talking about people who cannot use their own mind. They are being controlled by certain people in government to do things that they cannot even themselves imagine they have done as humans. They are being controlled, so we are not going to be threatened by people who we know are not acting of their own accord but are assigned by certain people because they are trained. So to us, they are like dogs; they’re taught to feed and not bite the hand that’s feeding them. Currently, they’re just taking certain leaders, arresting them, thinking that are those people are the ones instigating the strike. It’s not about one individual; you can kill one worker, you can arrest 20 leaders, but you’re talking about thousands of workers on strike who are actually responsible.

And by arresting someone or some among them, you are boosting the miners because there’s attention on us, it is being seen that we are doing something. Then, if they’re not arresting anyone, maybe it will demoralise us because no one will notice what is happening. Arresting someone motivates the spirit of the workers. They arrest them, they release them, still the strike continues. It doesn’t work, this thing that they are targeting certain people, because it’s not those certain people [causing the strike]. Even if you arrest us all or you kill us all, we’ll never change our demand of wanting the money that we want.

What had Lonmin been doing – had it been making threats to workers, had it been been trying to bribe people?

Lonmin is very clever; they are using our black people as their own frontees; you’ll find [Lonmin CEO] Ben Magara, you’ll find Cyril Ramaphosa putting these shares, they are being used because of their education – they’re thinking that the workers are not educated, so they can fool us. The matter of doing things is not in the matter of education, it’s the matter of the mind and conscience, if you have a conscience, you have the heart – so you can have degrees and everything but if you don’t have a heart you’ll always be a stupid person. It doesn’t mean that if you have been educated you are clever. Anyone can be educated.

So our ancestors were not educated but they were able to understand by the needs of what’s supposed to be done to live a life in this country without anyone being suppressed or being exploited – because this politics that we are in, it wasn’t started by current politicians; it has been fought by people who never attended any school. But what Lonmin specifically has done was to call certain leaders and certain workers to them and offer them 15%. We’re not taking that shit of 15%; we know that we want. Tell them if they want to talk to us we must talk about R12 500, not about 15%.

And, secondly, Lonmin is writing to the papers and circulating all that propaganda saying, no, it has agreed with AMCU and that they are prepared to pay workers in rands and cents, which is not more than R 10 000. We’ll not take the instructions from the employers, we want the instructions from our own official’s unions, especially leaders whom we trust – they’re supposed to deliver the message to us. The message cannot be delivered by the management to us. That’s the tactics that the company is using. There are people who died for this R12 500, and the union has taken the mandate of the people that they want 100% of this money.

I personally feel this is quite a historic strike. I feel like this strike is really the workers making a stand against all the problems in the mining industry that has been there for years, in which this money is going overseas to people in London rather than to the workers and people in South Africa. So it’s really, even though much of South Africa needs to support the workers, a strike that is a historical stand against what’s happened before. Would you agree with this?

I 100% agree with your opinion because as I speak to you currently I’ve got my own grandfather who is still alive. He was injured in forehead “the table”, as we call it underground, and he’s still injured. We live poor as South Africans; these mineral resources belong to us. These mineral resources are enriching other people in other countries. So as the current generation, we are saying that enough is enough, this cannot happen to our forefathers and still to us. We want to put a stop to it. This old man [his grandfather] cannot see anymore; he was dismissed because of the injury.

What organizations have been helping the workers with the strike? And what can people who want to help the miners and support the strike do?

The first organisation that helped us when we were abandoned by our own union that we elected in the majority of years, the National Union of Mineworkers, was AMCU. That’s the first organisation that we need to praise with its own president who has never changed our real demand, a total of R 12 500.

We cannot shy away from the fact that since the beginning of the massacre, we have been with the Marikana Support Campaign. All the comrades who are within the Marikana Support Campaign are supporting us. Even now, whenever we are arrested, whenever we go to the [Farlam] commission, they are around us – they are doing everything that they can to support us. Those are the two organizations that I will mention.

Currently we are just observing the moves of The Citizens for Marikana. They promised to assist us but haven’t so far showed how they are going to assist us, in what way. But they have said that they are coming.

And the fourth that I will never ever forget is the community members in Marikana – they are behind us. Those community members and community organisations, such as Sikhula Sonke, are the people behind our plea.

What we can be assisted with is that we need all the social movements behind us, they’ll see the way that we see things. We know that the people we are fighting are using the same amount that they are taxing us to fight us. So that’s why we need to unite – all the organisations need to unite – to fight the union bosses and the state. You see, now the state is in the middle of the workers and is supporting the side of the capitalists. So when any support, even 10 cents is contributed towards the strike, it helps us because we can’t turn away from those who cannot manage to have their own reserves. They feel the hunger because that’s the only strategy the companies can use, to hit us on the hunger : – any support and solidarity among the workers in all the organisations that think that it’s a historic fight.

How do you feel about the elections next month? Are you voting?

In my own view I will say that this shows all workers should go and vote but their vote much be tactical to reduce the power of the ANC. We must deal with the ANC once and for all and make sure that we take all the power from them. But they must know very well the person who they’re going to vote, when they do decide. We instruct that leader on what’s expected of them. So when they disappoint again because we need to have control over the people we elect so that they can deliver to us what we demand, because if we do not do that we’ll always be in the games of the other people, and other people will play the game that is supposed to be played by us. So this is our game because while it has been led by Jacob Zuma and Ramaphosa and Riah Phiyega …

Phiyega is worse because we expected women to be better people because we know that they are the ones who carry us for nine months as human beings. But that woman, the way she acts, she’s not a woman. So that’s what we need to do because of the current situation.

How do you feel about the Farlam Commission and how do you think it’s gone so far? I personally don’t think anyone’s going to get convicted but it seems like a lot of evidence is coming out showing the degree to which the bosses are involved in all the shady stuff.

What is annoying me with the commission currently is that it is clear, revealed by the work that has been done by documentary that was produced by Uhuru Production with the team within the Marikana Support Campaign, what happened. But now there’s this witness called Mr X. It’s annoying what we’ve been witnessing in the commission but this guy is going to be faceless. And this guy is admitting that he has killed people; that he’s a murderer. Why can this guy not show his face? And the worst part of it, you are very educated, you know that most of the people in the public say that X can testify; X is called to something. But why were we just told that Mr X is going to be faceless after he admitted that he has the tongue of the human being who he killed? He had testified that he slaughtered the black sheep and buried it in the mountain. We are saying this guy, if it’s true that he was there, they must and go search in all mortuaries and find the body without the tongue. They must go to the mountain and dig the bones of that sheep. And there’ll be a DNA test that will show that how old the bones that were buried are because there are scientists who are educated. That’s where we will show that that Mr X is not telling the truth about what happened at the mountain. There was no such a thing that we have done.

And, thirdly, which is very important, the killer admitting that he is a killer. We are saying we are not killers but yet this guy cannot be arrested. He can sleep in a smart hotel and do anything. Why should the commissioner allow such [a witness – unclear]? And we are fearing for the lives of the people who can be killed and are worrying about this thing. What about the people who have been with this thing? They’re not afraid of their own lives.

* This interview is reprinted here with permission from Amandla Magazine.

‘Dreams Close To Home’: In search of the perfect wall to paint in South Africa

Sometime last year, I attended an exhibition opening entitled “Dreams Close To Home” at the Two by Two Art Studio in Newtown, Johannesburg. It was the culmination of a self-initiated project by the artists Lisolomzi Pikoli (Fuzzy Slipperz, illustrator), Skhumbuzo Vabaza (Skubalisto, illustrator), and Karabo Mooki (Mooki Mooks, photographer) which saw them go across parts of South Africa in search of the perfect wall to paint, and swiftly proceeding to do so everytime they stumbled upon one.

The trip begun with Mooki Mooks’ and Fuzzy Slipperz’ train trip down to Cape Town where they connected with Skhubalisto. Thenceforth, they travelled by vehicle through the vast, lush winelands and beaches of the Southern Coast. They hit up spots in Jeffreys Bay, Port Elizabeth, and the former Transkei (all in the Eastern Cape Province); Mooki Mooks’ trusty camera captured the adventures. The three had their final stop in Johannesburg where they held their well-received exhibition.

Below is a conversation I had with all three on the day about being an artist in present-day South Africa. But first this short video interview and scenes from the opening night:

During the interview, transcribed below, the artists also touched on what it means to paint at home in South Africa as opposed to other countries they’ve visited.

As working young artists in South Africa, how do you survive?

Skubalisto: It’s tough skin and a positive mental attitude and drive. Sink or swim, you can never stop no matter what. At the end of the day, we feel more like [pioneers] because there’s not much of an industry. There are people who’ve done it before, but we’re trying to carry that torch and build that fire. It’s a tough industry, but it’s a beautiful industry and it’s fun!

Fuzzy Slipperz: Also, I think it’s important for artists to do projects independently, off of their own steam. RVCA helped us out in this whole thing, but me and Skhumbuzo had been thinking about it for a while. I think that’s quite important because everybody wants to make it into a certain gallery or be associated with certain brands. [I'd rather be known for] self-initiated projects that then get recognised. But it’s tough, [but] there’s no tough with us. This trip was, let’s just say the budget was tight, but we made it work!

Mooki Mooks: In actual fact, your art should speak [louder] than brands, and that’s what we tried to achieve. I’ve been documenting the trip; their art truly speaks louder. Without their art the brand’s nothing.

You’ve all spent some time travelling overseas. What were your experiences like?

Mooki Mooks: Norway was fantastic! I’m back to be back in the homelands though.

Skubalisto: I was based in San Francisco for a while, and that was my school of thought. That’s where I started painting, and that’s where I was influenced. There are a lot more artists there; there are a lot more people who pursue art as a career and take it professionally, so there was a lot more competition. At the same time, it feels that now I’m back home, my work has completely flipped, as opposed to when I was painting in the US. That’s the beauty of being back home; it feels like my work has found its soul a little more.

Fuzzy Slipperz: I was in Berlin for three months, and I did my first overseas exhibition. For me as a person who’s into art in general, street art or contemporary, it’s the hub! Even though I had a small gallery, I was treated really well. It was good to see an art-driven society. And though that was beautiful and it was really fun, [I got to] see my dream come true and whatever…I don’t think as artists we should ever really be satisfied. There are a lot of things that worry me about [our] socio-political as African people, as South African people looking toward a future – all these things are always on my mind. And I think that’s, in a big way, why we called this Dreams Close To Home. We’ve been travelling and doing all this stuff, but we grew up over here, and that’s the only thing that makes our art speak originally in any way – it’s our natural influences from where we’re from. What you want to do is carry on growing and understanding your own landscape; it’s what informs your art; it flows out naturally that way.

And how was it painting throughout this trip?

Fuzzy Slipperz: Travelling through there Eastern Cape, I go there during December for Christmas and all that stuff. It was cool to go the with my friends and do whatever we want–Port Elizabeth, Transkei, wherever! We me cool people, and we also got humbled a lot of the time. We didn’t get a lot of the responses that we’re used to; people were really engaging [and] forthcoming, or they just didn’t give a shit!

Skubalisto: A lot of the people were beyond curious. Their curiosity led them to a point where we’d be painting in freezing, howling weather – the weather sucked in PE! There were people who got there from the time we were setting up, and left when we finished.

Fuzzy: The content was quite an important part to us. We wanted to relate on a South African level. For instance, in PE we drew portraits of our mothers, our interpretations of their energy or essence. That for us is how the concept hit home; we were extending ourselves.

* All images courtesy of Karabo Mooki. You can follow the artists’ work on-line. Mooki Mooks here; Fuzzy Slipperz here; and Skuba here.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers