Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 370

January 13, 2015

Hipster’s Don’t Dance’s Top 10 UK-based Afrobeats Tunes of 2014

Hipster’s Don’t Dance wraps up our year end chart series by representing the contributions their home scene has made to the international Afrobeats sound. Check it below, and keep looking out for their great round-ups here on AIAC in 2015!

It’s been an interesting year for UK based Afrobeats, never more apparent in the mainstream but also still lead by one shining light Fuse ODG, who released an LP, refused Band Aid and then did his own song for charity in 2014. Moelogo got signed and had the song that ran the roads. Speaking of roads Peckham’s Naira Marley remains a fun outlier. Hagan and Major Notes brought the genre even closer to the UK clubs. Here are our top picks of 2014:

Fuse O.D.G. feat Sean Paul – Dangerous Love

Moelogo feat Giggs – The Baddest

Naira Marley – Marry Juana

Maleek Berry – Carnival

Dr Sid feat Alexandra Burke – Baby Tornado Remix

Kida Kudz feat EsDee YFS, Yemi Rush, Sona & Hakeem YFS – Ibere Remix

C’z CestLaVie – Comme Ca

Lola Rae feat Iyanya – Fi Mi Le

Major Notes – 419 Riddim

Hagan – The Music

Percy Zvomuya pays homage to historian Terence Ranger

In 2004, after Terence Ranger had delivered a paper at the Wits Institute of Social and Economic Research (Wiser), I went up to him to greet him, make a few comments about his lecture and introduce myself as Zimbabwean. I know, he responded.

Ranger’s paper, “Historiography, Patriotic History and the History of the Nation: the struggle over the past in Zimbabwe,” was one in which he critiqued the use of history by Zanu PF. The lecture came at the moment when the arc of the social and economic crisis had taken a sharp, jagged turn into the unknown and Zimbabwe’s history, and Zanu PF’s principal role in it, had become handy and expedient.

“There has arisen a new variety of historiography which I did not mention in my valedictory lecture. This goes under the name of ‘patriotic history’. It is different from and more narrow than the old nationalist historiography, which celebrated aspiration and modernisation as well as resistance. It resents the ‘disloyal’ questions raised by historians of nationalism. It regards as irrelevant any history which is not political. And it is explicitly antagonistic to academic historiography,” Ranger argued.

The irony and force of his argument wouldn’t have escaped anyone vaguely familiar with the historian’s work. His two books: Revolt in Southern Rhodesia (Heinemann), which came out in 1967, and The African Voice in Southern Rhodesia (Heinemann), which came out three years later, in 1970, are, by his own admission, nationalist historiography “in the sense that they attempted to trace the roots of nationalism.”

The two books, which the more literate of the nationalists must have read and re-read, came out a critical juncture in the nationalist struggle: in 1963, Robert Mugabe and others had broken away from Zapu to form Zanu; in 1965, Ian Smith had announced the Unilateral Declaration of Independence; because of Smith’s intransigence, armed struggle had been adopted and, in 1966, the first shots had resounded in the limestone and dolomite country of Chinhoyi. The two books were useful not only in understanding the heroic past of struggle and revolution but, also, how that 1896-97 war against the British settlers and its mythic protagonists – Nehanda, Kaguvi and Murenga – linked up with the nationalist present fight. The name Zimbabwe, coined by nationalist Michael Mawema, after the majestic stone walls in Masvingo, was part of this reclamation of a great romantic past of empire and its attendant monuments. Although the Great Zimbabwe monument pointed to a fully-fledged civilization, its sophistication and neat geometries were of no use at that point. What they were looking for in their past was mess and gore, the battle axe and the shield, in other words, revolutionary violence.

Writing Revolt: An Engagement with African Nationalism (Weaver Press), Ranger’s memoir of his time in Rhodesia before he was deported by Smith’s government in 1963, came out in 2013. In the preface, Ranger wrote, “this book is about a primitive stage of Zimbabwean historiography. It is also about the ways in which politics and history interacted. The men I discussed history with were the leaders of African nationalism; my seminar papers were sent to prisons and restriction areas. Both they and I were making political as well as intellectual discoveries.”

He then made a provocative comparison with another colonised people, neither Asian nor African, but European. “I had worked previously on Irish history. Now I found again a context in which history was too much important to be left to historians.” The hegemony of patriotic history, the way that history has been abused and misused, has also taught us that history is too, too important to be left to politicians.

Robert Mugabe plays a starring role in these narratives; he has, naturally enough, made the most use of this patriotic history. Ranger, writing about Mugabe in the aftermath of his arrival from Kwame Nkrumah’s Ghana in the early 1960s, observed that “Mugabe was new to us and lying low in the National Democratic Party (NDP)”. The NDP is one of several nationalist parties that was formed and banned by the Rhodesians. “We watched him closely to try to pick up some clues.” They saw a “rare playful moment” at a dinner table one evening. After wolfing down his food, Mugabe turned to his friend and fellow nationalist Leopold Takawira, and said, “I am surprised at you, Leopold. As a good Catholic you are eating meat on Friday.” An “upset” Takawira pointed out that Mugabe himself had also eaten meat. “Ah, but I am not a good Catholic.”

Ranger’s oeuvre is vast and stirring. If his early works easily fell prey to the machinations of the nationalists, his later works were much more sophisticated. There are the early works Revolt in Southern Rhodesia, 1896-97 (Heinemann) and Peasant Consciousness and Guerrilla War in Zimbabwe: A Comparative Study (James Currey). Co-edited with Ngwabi Bhebhe is the book Ranger titled Soldiers in Zimbabwe’s Liberation War (James Currey). He also wrote a portrait of a very political family, the Samkanges, titled Are We Not Also Men? The Samkange Family and African Politics in Zimbabwe, 1920-64. (James Currey). There is another collaboration with Bhebhe, again as co-editors, Society in Zimbabwe’s Liberation War ( James Currey).

Most of his work, even though national in scope, had a northern Zimbabwean slant. But in his later years, he took a decidedly southern outlook. The first of these books was Voices From The Rocks: Nature, Culture and History in the Matopos Hills of Zimbabwe (James Currey) and with his two students, Jocelyn Alexander and JoAnn McGregor, Violence and Memory: One Hundred Years in the ‘Dark Forests’ of Matabeleland (James Currey) and Bulawayo Burning: The Social History of a Southern African City (University of Western Cape). Then there was, with Eric Hobsbawm, the celebrated tome, The Invention of Tradition (Cambridge University Press), a co-edited book that showed how “continuity with the past” is constructed by use of rituals, symbols and practices, how some of the things we view as traditions are, in fact, invented.

A former schoolmate once described Ranger as an “ordinary boy”, so ordinary, in fact, that he failed his mathematics, was dismal in French, and failed Latin so frequently that he went to Oxford a term late. Not that he was any better in the sciences, a faculty that would have been useful in his father’s electro-plating factory. So how did an ordinary boy collaborate with some of Europe’s most formidable minds? How did he stake out a ringside seat as witness to the first stirrings of African nationalism? How did he become midwife to generations of exceptional historians? How did he do it? Well, for starters, he had a brain for literature and history.

“My parents gave me what I needed to feed on – countless holiday visits to cathedral towns and castles, and a reasonably well stocked library at home (which contained most of Dickens, for example),” he wrote.

Ranger’s education on Africa, if we are mad enough to conscript some of the racist writings of Rudyard Kipling, Rider Haggard and Joseph Conrad as being about Africa, hadn’t exactly prepared him for his career. “I have often thought about the odd effects of such a literary education which has left no trace on my adult responses to Africa. We did not know any Africans personally; there were no African boys at Highgate School, though there were Greeks and Armenians and German Jews.”

Oxford, of course, would not educate him about Africa. “The core of the History Honours syllabus was a continuous knowledge of English history. I heard about Africa only in the context of Prince Henry the Navigator.” His graduate supervisor, Hugh Trevor-Roper, would gain notoriety in African/Africanist circles when he said, “Perhaps in the future there will be some African history to teach. But at present there is none, or very little: there is only the history of Europe in Africa. The rest is largely darkness.”

Yet it was also at Oxford that he met one Carl Rosburg, who was researching and writing on the history of the Mau Mau, work which would culminate in the book, The Myth of “Mau Mau”: Nationalism in Kenya. “Like all proper young Englishmen I regarded Mau Mau as the height of barbarity, and I was astonished when Rosburg insisted that it was instead a rational nationalist movement. A few years later it was Rosburg who introduced me to the Southern Rhodesian African nationalist leaders.”

Before deciding to settle in Africa, at the age of 27, Ranger almost accepted a position at a university in Malaysia. But he happened to read a piece in The Times by Basil Fletcher, then vice-principal of the recently opened University College of Rhodesia and Nyasaland (now University of Zimbabwe). “The college, its copper roofs gleaming in the sun, was a beacon of hope between the white nationalism of South Africa and the black nationalism of East Africa. It stood for partnership and multi-racialism. At once I decided that this was the place for me.”

The rest, as they used to say, is history.

If Ranger’s life is an object lesson for whites, those born on the continent or arrivants, then it is perhaps in how he arrived in Africa and then, as in the cliché, he set out to find himself and steered clear of the play of stereotype and received routine. “I was a married man with two-thirds of a doctoral thesis written. But there was a lot I did not know. I did not know whether I had physical or moral courage; whether I could bear being wildly unpopular; whether I could take –or follow – a lead; whether I could throw myself into a cause; whether my historical imagination could expand to embrace a whole new civilization.”

Ranger has now gone. He is not only a chief protagonist in the invention of a tradition and a mythology, but a whole historiography. When his historiography had been exploited by the Zimbabwean state, he was one of the first to revise and interrogate his initial ideas. Not that he should have done so because a new generation of Zimbabwean historians, some of them his students, were at hand to critique their teacher.

Jesus, that good Nazarene, in his attempt at disrupting the student-teacher hierarchy, once said that the student is not above the teacher, but everyone who is fully trained will be like their teacher. And one of Ranger’s most fascinating students is Sabelo Gatsheni-Ndlovu who, like all good students, has up turned Ranger’s early nationalist historiography on its own flag-bedecked head. Writing in the introduction of his Derridean book, Do Zimbabweans Exist?, Gatsheni-Ndlovu argues that his work’s aim is to transcend studies “in the service of nationalism” by scholars such as Ranger, David Martin and Phyllis Johnson. “These texts were easily appropriated by the Harare regime because they celebrated nationalism, painting a false impression of nationalist actors as heroic figures and selfless people who genuinely worked and died for the masses.”

In Ranger, politics and history, nationalism and scholarship, intersected in a jagged geometry rarely seen.

Zimbabwe, Africa, will forever be in his debt.

* This piece first appeared on The Con Mag. It is republished here with permission from the author.

January 12, 2015

The Trials and Tribulations of Simone Gbagbo

Simone Gbagbo, ex- First Lady of Côte d’Ivoire, is currently on trial in her home country. She faces charges of “undermining state security” during the post-electoral conflict of 2010-11. Although she is only one of 82 defendants in these proceedings, she stands out not only due to her former status and function, but also because she is wanted by the International Criminal Court (ICC), where she is alleged to bear criminal responsibility as an indirect co-conspirator on four counts of crimes against humanity.

Simone Gbagbo is the first and only woman so far to be charged by the ICC. Her husband Laurent Gbagbo, and Charles Blé Goudé are already in custody in The Hague, waiting for their day in court.

The aftermath of the 2010 presidential elections in Cote d’Ivoire unleashed six months of unrest, political violence and gross human rights abuses that left 3,000 people dead. These were supposed to be the elections that would move Cote d’Ivoire past the civil war and de facto partitioning of the country since 2002. But a struggle for power ensued when Gbagbo declared himself the winner, despite being defeated by Alassane Ouattara, who was backed by France and most of the international community, including the United Nations.

It is not easy to assess the extent to which Simone Gbagbo was implicated in the post-electoral conflict or responsible for specific acts of violence. But it is clear that Simone Gbagbo was not your typical First Lady. Simone Gbagbo is no Chantal Biya. She was a political leader in her own right. Her life until the year 2000 when her husband became President of the Republic of Cote d’Ivoire is nothing but courageous and praiseworthy. At age 17 already, she led a strike in her high school and was arrested, before joining clandestine Marxist groups. It is through those clandestine groups that Simone Ehivet met a young and charismatic history professor, Laurent Gbagbo.

She co-founded the Front Populaire Ivoirien (FPI) with Laurent Gbagbo while in exile in 1982, during the all-powerful Félix Houphouët-Boigny’ s one-party rule. Even after the political landscape opened up in the 1990s, FPI leaders still succumbed under the repressive force of Houphouëtism with Alassane Ouattara as Prime Minister. Alongside her husband, Simone Gbagbo is arrested multiple times, jailed and abused. In prison, she became a born-again Christian and later flirted with Evangelicals, which, some argue, spiraled into her downfall.

She was later elected as a MP and president of FPI parliamentary group, often painted as the proverbial formidable wife at the side of an ambitious husband or the too ambitious woman that pushed her husband to the breaking point. And they reached that breaking point one fateful day of April 2011.

But the prosecution of Laurent Gbagbo, Simone Gbagbo and Charles Blé Goudé is as much about law as it is about domestic politics. Whereas the Ouattara government has surrendered Laurent Gbagbo and Blé Goudé to the ICC, it has refused to transfer Simone to The Hague, opting to have her face justice in Côte d’Ivoire. The ICC will probably never lay its hands on Simone, because you just don’t ship a 65-year old African lady to The Hague. That would be political suicide, and Ouattara knows it.

Moreover, trying Simone Gbagbo before domestic courts gives the government an opportunity to use her as a leverage in the fragile national reconciliation agenda by either pardoning her or putting her under house arrest for example. With the uncertainty surrounding the next presidential elections which are scheduled for October 2015, the trials of Simone are prescient. Much more prescient than Laurent’s attempt to run the FPI from his prison cell in The Hague.

For better or worse, the future of Cote d’Ivoire is linked to the present and presence of the Gbagbo couple in Yamoussoukro and The Hague’s courtrooms. Côte d’Ivoire, which wasn’t even an ICC member at the time of arrest and surrender of Laurent Gbagbo, is one of the most fascinating and intriguing situations in which the Court is involved in Africa. Ironically, one little known fact is that it is Laurent Gbagbo himself that first recognized the ICC jurisdiction by sending an invitation letter to the Prosecutor in 2003, following the first Ivoirien civil war. President-Elect Ouattara sent a new letter to the ICC on 14 December 2010 extended a second invitation to the ICC in the aftermath of the 2010 elections.

January 9, 2015

Digital Archive No. 8 – World War I in Africa

In honor of the centenary of the Great War, Jacques Enaudeau and Kathleen Bomani set out to bring attention to the forgotten story of Africa’s involvement in World War I. As Enaudeau, a French geographer/cartographer, and Bomani, a Tanzanian activist (and frequent contributor to Africa Is A Country), rightly point out, “the story of Africans’ involvement in the Great War is largely unheard of.” Taking the hundredth anniversary as not only an opportunity to uncover this history, but also using it as “a fertile common ground for investigating the present,” their project, World War I Africa, is a platform for exploiting this “window of opportunity to connect the dots and discuss the knots, to challenge the boilerplate narrative and change the usual narrators.”

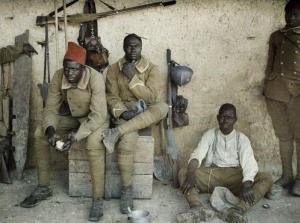

An Askari member of the Lettow-Vorbeck Freikorps in Munich, May 1919

As the subtitle of World War I Africa states: “What Happened in Africa Should Not Stay in Africa.” And what this project has done is begin the process of making sure that these stories find their way to a broader public. Not a full year into the four-year centenary, this website has begun to accumulate a series of stories and sources, preserving these histories and beginning a conversation that will continue throughout the next four years and, hopefully, beyond. The fourteen articles currently featured on the site cover a range of topics, from the history of Askaris to Marcus Garvey’s opinions of the war to the Constellation of Sorrow Memorial to Senegalese tirailleurs fallen in France and a brand new piece on Ethiopia’s path through the war. Obviously, this site is a work-in-progress, with a small range of stories (some of which have been published elsewhere previously), and the creators are, of their own admission, no experts (in their first Africa Is A Country feature on World War I Africa, they admitted that they “claim no expertise” and “aim to educate ourselves as much as we hope to teach others”). But, with these caveats, this project already sheds new light in ways that suggest that what will come in the next three years holds the potential to have a broad impact in how we conceive of and talk about these important historical moments; moments which have largely been forgotten in popular memory.

Senegalese tirailleurs in Saint-Ulrich (Haut-Rhin), France. 16 June 1917. Photo by Paul Castelnau. Source: Ministère de la Culture.

Though the bulk of the original content of the project exists on the main site, these articles and links should really be supplemented by the rich variety of materials contained within the Tumblr. Including links to other stories related to Africa’s role in and experience of the Great War, this Tumblr also incorporates more of the stunning images which make this project so visually dynamic. These images serve not only to put faces to the stories uncovered by this project, but also as a window into the rich resources available online for those interested in pushing further. Utilizing the links from Tumblr and the Resources page, interested users can find recommended readings, digital bibliographies, and online image collections; materials which all provide an additional window through which to begin exploring these histories.

In announcing their plans for the project, Enaudeau and Bomani entreated their readers to “unpack what the world thinks it knows, and put what it should not ignore right under its nose.” So, get reading and let’s make sure that the centenary is a celebration of the world’s experience in World War I. Follow World War I Africa on Facebook, Twitter, and Tumblr.

As always, feel free to send me suggestions in the comments or via Twitter of sites you might like to see covered in future editions of The Digital Archive!

The Five Phases of Blackness: Why #WhiteLivesMatter

You are probably wondering about the title. I suspect that you are eager to get to the clever (perhaps desperate) twist. There is no twist. White lives matter!

You may even be wondering what I mean by blackness. Blackness is exactly that, suffocating darkness. Imagine being in a dark tunnel that is shut on both ends. Except, this tunnel is centuries long, the walls are drenched in blood and the floor has piles of black bodies. There is no light, maybe just a flickering candle that is seen only by a lucky few.

The first phase of blackness is innocence, oblivion. As an infant, a black infant, born to black parents, in a blank community, I was unaware of my blackness. I was oblivious to the curse that plagued me.

I imagine that I poo-poo-d like other children. I mama-d and dada-d, like other children. I guzzled milk formula and stuffed by face with Purity, literally.

As I crawled and then walked, I didn’t know that I had survived higher-than-average infant mortality, malnutrition and poor health care. In a rural village in South Africa, I drank water from a river (that also doubled as a toilet and a bathtub). However, just by staying alive, I passed to the next phase of blackness.

The second phase is confusion. Like most children, I woke and donned my khakis with long socks. I polished my shoes, combed my nappy hair, stuffed by face with yesterday’s leftovers and walked for about an hour to get to school. But even then, as a black child, at a black school, in a black community, there was a pervading sense of otherness.

The language and mannerisms enforced at school were alien and awkward. It felt as though the school was teaching me to become a different parson; a person I had never met. In each book I read, Africa, my home, was either a strange dessert roaming large elephants or a large forest roaming tempestuous baboons. The people were simple, hungry, diseased or just in need of salvation.

It was all very grotesque and unfamiliar. More so because my family’s kraal (a compound of houses) rested on a riverbank, surrounded by a lush green of rolling mountains as far as the eye could see. Every morning I woke up to the crackling of birds that nested on a bamboo forest across the river. As the village came alive, and the river fog cleared, there were neighbours shouting, dogs barking and roosters crowing, but never the stampede of elephants or grinding fear of wild lions that I read about in schoolbooks.

I listened carefully in every class – in history, geography, maths, and science. Blacks were either not mention or were mentioned only as subjects in the enthralling tales of European conquerors. Even in art class, the village patterns were taboo. I had to draw a car or a multi-storey house, never a village rondavel, a herd of cows or pack of hunting dogs.

So I started asking myself, “What is wrong with us?” I remember as a child asking my folks, “Why are we not white people?” I remember asking my mother – a very light-skinned woman who had to cover her face with red clay as she toiled the soil during the unforgiving summer sun – whether the clay (“ibomvu”) would make her a white person. She laughed as said, “If you want to be a white person, do your homework.”

An exam in IsiZulu is “ukuhlolwa,” which unfortunately translates to “inspection”. One morning, when I was about seven years old, I refused to go to school. When my mother asked why, I told her that inspectors (“abahloli”) were coming to check if we were white. She laughed and said, “You did your homework; you will be fine.” I cried and told her, “My skin is still dirty.”

Even then, at seven years old, just three years after democracy in South Africa, being “unwhite” felt like a problem, a curse and a mistake. I couldn’t put my finger on it. I was not aware of the bigger picture. W.E.B du Bois asks the same question in his book The Souls of Black Folks, “How does it feel to be a problem?”

The third stage is the awakening and shame. If you’re lucky enough to pick up a book, your awakening will be delivered quickly by King’s dream, by Malcolm’s passion or by Garvey’s pragmatism. Perhaps your awakening will be through Césaire, Fanon or Biko’s sharp wit. They will bite and blow. They will tell you about the roots of black pain and disadvantage but still remind you to love yourself.

If, like me, you are not that fortunate, your awakening will be slow and excruciating. For me, it took watching movies portraying lynching and murder of blacks to loud cheers. I watched on television as black bodies were mutilated and burned for sport.

I watched in awe as every black man was portrayed as gun-wielding buffoon. Every black woman was portrayed as powerless and mindless domestic. If not that, black women were portrayed as prostitutes, like no other black woman I had ever seen. The village women, their strength, dignity and human spirit, were not portrayed on television.

First, my blood boiled and my heart was drenched in senseless hate. I cried myself to sleep. Soon, the anger morphed to shame. I felt naked. My very existence, it seemed, was a cruel joke. If there were ever any ancestors, if there was ever a God, how dare they let us suffer for so long? How had we allowed ourselves to suffer for so long?

I then looked around my own community. Families were crumbling as fathers left young children to search for work in city slums. They came back only once a year, for a week (or maybe less) in December. Rumours soon spread that, after years of loneliness in piss-reeking Durban or Johannesburg informal settlements, they took mistresses or raised clandestine families. As families drifted further apart, young teens, male and female, were forced to leave school to provide for the family thus completing the cycle of black disadvantage.

The fourth phase is anger. I became very angry about the past. Most of all, I was furious about the present. It did not matter how hard I worked or how many books I read, I would forever be an outsider. Where, with a mixture of chance and hard work, I succeeded — I did so only to become a token. “You are not like other blacks,” they told me.

I was angry because the facts are widely available. There are troves of garish books, documentaries, movies, and other art forms. There are museums, biographies and first-hand accounts of centuries of black pain. Yet, people (blacks included) appeared to be oblivious to the fact that we are suffocating and slowly self-destructing because of reminiscent oppression.

I was angry because I finally realized that the world hates slavery and colonialism, not because of the pain and suffering of million of black individuals, communities and nations, no! Leopold II killed between 8 and 10 million Africans, but, even today, monuments celebrate him in Brussels.

The media reported recently that white police officers in Ferguson, Missouri, beat up a black man. When he bled on their uniforms, they charged and jailed him for destruction of public property. In a similar vein, the world hates slavery because it is an ugly stain on the conscience of white folks; those who care enough to think about the subject anyway. This explains the doublespeak — Belgium and the United States denounce slavery but still celebrate slaughters like Leopold II and Columbus.

The fifth and final phase of blackness is survival. I am tired of being black. I am tired of the abuse, of being a victim, of the anger and shame. I do not want to run from the police, from poverty and diseases. I am tired of being hounded (physically, emotionally and psychologically) by whites and uppity blacks. I am tired of dodging bullets from hardened, angry and hungry black youths. I am tired of policing racism and bigotry.

I am tired of pleading just to be recognised as a human being. I am tired of fighting for, and then having to defend, my humanity – the most obvious bit of my existence.

I want out. Give a seat at the white table! I will be a good black. I will stop listening to hip-hop (just Iggy Azalea and Macklemore). I will never speak again about slavery, race or white privilege. I will work harder for half (or less) the reward given to my white counterparts. All I want, all I need, is just to live!

Black lives do not matter! From the bondage of slavery, to the bondage of nations under colonialism, to modern government-sanctioned corporate slavery, black lives do not matter! I am willing to shut up about that.

I am willing to validate my existence to the “Aryan race”. I will assimilate whiteness, if that is what it takes. I will “speak properly” and I will pull up my pants. I will apologize for black slaves that bled on white masters. I will apologize for King’s silly dream. I will apologize for Malcolm, Garvey, and Biko’s radicalism.

For all this, I ask just for one thing: the right to be alive!

January 8, 2015

Will Chikungunya be the Media’s New Ebola?

Chikungunya is a virus transmitted by a mosquito bite. There is currently no vaccine, or cure for it, other than letting the symptoms flow their course. It is not lethal, but it is painful and debilitating, causing high fevers and pain in the joints, usually for months. And even though it was discovered in 1952 (in Tanzania), this is probably the first time you are hearing of it. If it’s not, maybe the first time you heard about it was last week, when American actress Lindsay Lohan said she had caught the virus during her vacation in Tahiti, in the French Polynesia.

The incident prompted many media outlets in the United States to report on Chikungunya, some with more dramatism than others. For example, on the first day of 2015–also prompted by the fact that the United States government had recorded 2000 cases of the disease in the last year there–NPR opened a piece with: “Most of us will remember 2014 as the year Ebola came to the U.S. But another virus made its debut in the Western Hemisphere. And unlike Ebola, it’s not leaving anytime soon.”

That’s an odd thing to say, since Ebola is still very much a problem in West Africa. But I guess the phrase refers more to the mediatic standing of that virus in the American media: Ebola has left the collective consciousness of the United States and has left an opening for Chikungunya, a new foreign ailment to be afraid of. If that is the case, NPR might be on to something, because indeed, the Western Hemisphere has been paying attention.

Until 2006, all of the cases of Chikungunya had been reported in Sub Saharan Africa (“chikungunya” means something like “that which bends up” in the Makonde language of Tanzania and Mozambique) and South and Southeast Asia. But a current outbreak has affected most of the Caribbean and it has reached parts of the Pacific Coast of Central America.

It started in late 2013 in the French part of St. Martin, and by July of last year there were 5000 confirmed cases throughout Latin America. By then, 21 people had died in the Caribbean because of the virus. Even though, as I mentioned, the Chikungunya virus is not lethal, it can be deadly for people with poor defenses, such as people who are already sick with something else, or people past a certain age. So we had been following the virus developments.

Puerto Rico officially declared a Chikungunya epidemic in July. Venezuela has been scheduling fumigations around the country to combat Chikungunya and Dengue. In Colombia, where I’m writing this right now, Chikungunya was the major public health concern of 2014, and it is still in 2015. Media here started following the virus in July, and coverage started to grow after August, when the first case in the country was reported. Now, most Colombian media outlets have sections exclusively dedicated to the virus and the disease it causes. Both the Minister of Health, Alejandro Gaviria, and the President, Juan Manuel Santos, have had to make various public announcements about them.

Currently, there have been 75,000 cases reported in the country (and very likely many more unreported), most of them concentrated in the Caribbean, or Atlantic region of the country. There, the weather–hot, humid and in proximity to various big masses of water–helps the Aedes aegypti mosquito, the bearer of the virus, to thrive. For now, the only precaution that works is to avoid being bitten. That means either buying bug spray, or moving away from places with mosquitoes. Yet, most of the cases have been reported in the periphery, and most of the people infected come from lower classes. Many people are too poor to afford continuous use of bug spray, while mosquitoes are everywhere, especially in poorer neighborhoods, with not good enough sewage or garbage disposal plans.

Other areas of the Caribbean have similar conditions and so it seems that, unfortunately, the virus will keep spreading along the region, including in the American state of Florida. Then, NPR’s prophecy might become true. In their article, Walter Tabachnkick, an entomologist working in that state, says: “There’s very little predictability for Chikungunya. But would 50,000 or 100,000 cases in Florida be surprising? I don’t know. I don’t think so. I wouldn’t be surprised.”

There is room for Chikungunya to grow and become the misinformed panic that Ebola was in the United States. And, as we have seen with Ebola in Western Media, these media frenzies are usually discriminatory. It happened too with Chikungunya in Colombian media: coverage of the virus truly blew up last December, when many wealthy people from the big cities in the center of the country (up in the Andes, where few mosquitoes live) headed for vacations to cities and towns along the Atlantic coast, or in lower altitudes, where the weather is nicer, but mosquitoes are more common.

Spanish-Colombian commentator Salud Hernández got the virus a few weeks ago in a trip to La Guajira, in the north of the country. She used one of her weekly columns at El Tiempo newspaper, usually dedicated to talk about politics, to tell the story of her disease and how doctors in Bogotá–where supposedly the best medical facilities are–were completely unequipped to treat her. She made the point that, since no one powerful from the “center” of the country had gotten the virus, there had been no national campaign to coordinate medical efforts against this virus, thus damaging the health of those in the poorer, more vulnerable areas.

We’ll see how it turns out to be in the United States. Will Chileans be discriminated because they come from the Chikungunya land of “Latin America” (Just like, say, Rwandans were with Ebola)? I don’t know.

In the meantime, tell Bob Geldof we already have a song for Chikungunya.

Making Sure We Give Credit Where It’s Due in the Ebola Outbreak

As a brutal year comes to an end in the West African countries that are fighting Ebola, it’s important to take a moment to appreciate those on the frontline. Much has been written and said about the international response – some of it rightly flattering to the foreign medical workers who put their lives at risk to treat patients, along with well deserved criticism of the bureaucratic inertia and sociopolitical blind spots that contributed to the crisis’ severity.

What shouldn’t get lost is just how much of the response has fallen on local shoulders. And how well those shoulders have carried Ebola’s weight, often with very limited resources or support. There’s a narrative out there that attributes the drop in Liberian cases, for example, to a ramped up international effort to fight the disease. There’s no question that the supplies, clinics, and lab equipment that were furnished by the world have been crucial, but Liberians deserve tremendous credit for what’s been accomplished so far.

In early September, it would have been hard to exaggerate just how overwhelmed the country was in trying to deal with Ebola. At that point, there was only capacity for about 300 patients in the three treatment units in Monrovia. When the WHO finished equipping a new clinic called “Island” in late September, it filled up the day it opened its doors. Those of us who were covering the crisis expected things to keep getting worse – Island’s opening was a relief, but the assumption was that it would only take a few days before the overflow cycle started anew. Numerically, this is where the situation looked like it was headed.

The thing is, it didn’t happen. Journalists scratched our heads over dinner, wondering what was going on and whether people who had come to see the units as death traps had decided to stay home instead of seeking treatment. It didn’t make any sense for there to be visible evidence of a case decline the same week the CDC had ominously raised the prospect of hundreds of thousands of deaths. What could explain this?

In retrospect, the answer was right in front of us. Every time I went into a Monrovian neighborhood, there was some kind of organic awareness campaign happening. Young girls in their school uniforms marched in the streets yelling at people to wash their hands, Liberian musicians released songs about the disease or held Ebola-themed courtyard freestyle sessions, and civil society groups distributed buckets in far-flung regions. The opening of new treatment centers was crucial in isolating contagious people, but the main reason that Ebola cases dropped in Liberia is this: people in Monrovia adapted to the threat they faced and started taking precautions against the disease.

The assumption that Liberians would not make behavioral changes in the face of Ebola was at the heart of the idea that the caseload would skyrocket indefinitely. This reflected a misunderstanding of the social dynamics that laid the groundwork for the Ebola epidemic. Liberians weren’t refusing the advice of government and medical agencies because they were superstitious or incapable of grasping the danger they were in; it was that they didn’t trust those bearing the message.

Once people started seeing neighbors and friends die, there was a collective effort to do whatever needed to be done to stop the disease from spreading. Some of the awareness campaigns were supported by funding from the world, many others were grassroots and led directly by the communities that were at risk for Ebola. As aid workers fled en masse, Liberians drew from the same tenacity and self-reliance that carried them through years of war. This is worth noticing for a world that often acts as if the obstacles to Africa addressing its own problems are rooted in attitude or “capacity” rather than structure and model.

On the note of capacity, it’s worth casting an eye toward the health workers who were directly responsible for treating patients. Many people, when asked what an “Ebola doctor” looks like, would probably imagine those who were most visible in the international media: Western aid workers. The truth on the ground was obviously very different. African doctors, some from the region and others from countries like Uganda, worked for months in Ebola clinics, and have rightly been praised as heroes in their home countries.

Some have had moments of international visibility, as when Time chose Liberia’s Dr. Jerry Brown to grace the cover of their magazine. Others toiled away in relative obscurity, like Uganda’s Dr. Attai Omoruto, who inspired both awe and fear in journalists as she warned that she’d throw us in jail if we tried to rob Ebola patients of their dignity by photographing them in the ward. It’s worth noting that the wards run by African doctors tended to take higher risks in treating patients with intravenous fluids than those run by some aid organizations, and that they may have consequently achieved higher survival rates.

These professionals deserve to have the outsize role they played in fighting the outbreak recognized by the world, particularly given that so many of them paid the ultimate price for their bravery and commitment. This is why it was particularly jarring when CBS’ Lara Logan neglected to conduct any on-camera interviews with Liberian health workers in her infamous 60 minutes piece last fall. Whitewashing Liberians from the Ebola response was an ugly journalistic failure that should serve as a reminder of the arrogance that assumes aid workers are more competent than their African counterparts.

Liberia’s Ebola doctors are, of course, supported by a multitude of rank-and-file health workers and technicians, many of whom draw absurdly low pay despite the dangerous conditions they face. Volunteer ambulance drivers worked ten-hour days last fall, some of them contracting Ebola in the process. Burial teams entered communities at great personal risk to safely dispose of the dead. Liberian nurses worked tirelessly despite going weeks without receiving their salaries. Volunteer contact tracers wound their way through the maze of Monrovia’s densely packed neighborhoods to follow up with those who had touched or encountered the sick.

The epitaph of West Africa’s Ebola crisis is hopefully not far off from being written. But when it is, let’s hope that the story we remember isn’t entirely one of death, suffering and institutional failure. What I saw in Liberia last September reflected some of the most flattering angles of humanity. When I asked people why they were taking the risks to move a dead body or treat a sick woman, the response was nearly universal: “This is my country and if I don’t do it, who will?” Ebola showed the world that there is still much that needs to change in Liberia and its neighbors, but it should also show us just how much those countries have to be proud of as well.

In honor of the Liberians who fought Ebola this year, I’ve put together a short set of clips I took last September. This, too, is the story of the 2014 Ebola outbreak:

January 7, 2015

Hipsters Don’ t Dance’s Top 10 African/Caribbean Collaborations of 2014

2014 was a year when our musical worlds began to collide and we saw an increase in African artists working with artists from the Caribbean. This is a really big development as some DJs have seen similarities between the musical styles for some time, now artists are jumping on board and helping the sound to develop and grow. Although we still can’t figure out the government endorsed cultural link between Trinidad and Nigeria (Calabar in particular.) We have seen a sudden explosion of these 2 cultures colliding, with the most successful collaboration being Timaya and Machel Montano’s Shake Yuh Bum Bum. Similar artists teaming up together created something magical and we hope that they do it again. M.I. featured Jamiaca’s Beenie Man on his LP and Samini had Popcaan on a single as well. Busy Signal lead the way merging dancehall and afropop with his versions of P Square’s Personally and Mafikizolo’s Khona. We are glad that these artists are working together, not only does it broaden their appeal but selfishly it provides us with more ammunition for the clubs! Here are our top picks for 2014:

Timaya feat Machel Montano – Shake Yuh Bum Bum (Official Soca Remix)

P-Square feat Sizwe – Alingo (Victorious Remix)

2face Idibia feat Machel Montano – Go

M.I feat Emmy Ace and Beenie Man – Wheelbarrow

Samini feat Popcaan – Violate

Ding Dong – Ginja

Kalado – Personally

Busy Signal – Professionally

Busy Signal – Bou-Yah (Vampire Teeth)

Fuse O.D.G. feat Sean Paul – Dangerous Love

Havana and Washington: On African Time?

Was it ever in doubt that the first African American president of the United States would wish to crown his legacy by normalizing relations with the most African island in the Americas? Few among us Cuba-watchers doubted that, should Barack Obama secure a second term, it would only be a matter of time before moves to repair the rift between Havana and Washington began in earnest. Blood-ties aside, US business interests have watched in frustration as economic rivals such as China made increasing inroads into the Cuban economy. But given the prime position that Africa has held in Cuba’s foreign policy ever since Che Guevara’s first visits to newly-independent countries in 1959 and 1965, what does the latest thaw in diplomatic ties between Havana and Washington mean for the continent?

It all depends on how extensive and far-reaching the changes become. For instance, should the economic embargo or Helms-Burton Act be dismantled, this would open the way for countries such as South Africa, which have long provided economic assistance to Cuba under the umbrella of development, to pursue more direct trade and investment agreements. And since South Africa and, old Cuban ally, Angola are joined in a friendly economic and cultural rivalry, it surely wouldn’t be long before the MPLA would appeal to the ties of history to lay claim to most-favoured nation status.

As for whether the countless urban and rural communities in Africa would continue to benefit from the thousands of Cuban doctors providing sorely needed medical services, much depends on the rival opportunities that might be created. Under current conditions, there are important perks and benefits that accrue to Cuban healthcare workers who opt to take up service posts overseas. At the same time, there have been accusations that medical internationalism has undermined the formally high standards of healthcare provision at home, as highly trained personnel seek out the greater compensation attached to, say, staffing a clinic in Luanda or fighting Ebola in Sierra Leone. Prior to the round of salary increases for medical personnel in 2014, the average salary for doctors working domestically was $30, compared to the $200 to $1000 earned by their counterparts stationed outside the country. However, an increase in economic opportunities on the island could change all of that, if increasing investment were to lead to higher salaries and a wider range of opportunities linked, for instance, to the almost certain development of the medical tourism industry in Cuba.

Any initial shortfall in the number of internationalist doctors, on the other hand, could eventually be remedied so long as Cuba continued, or even ramped up, its medical training programme for overseas students. This is perhaps the most important aspect of Cuba’s medical diplomacy, and the one that African nations should be most motivated to safeguard.

For the African diaspora, especially African Americans, the thaw in relations could see a rekindling and even a strengthening of the pre-Cold War relationship that Lisa Brock and Digna Casteñada Fuertes portrayed in their 1998 book Between Race and Empire: African-Americans and Cubans before the Cuban Revolution. And, at the very least, Afro-Cubans could hope for easy access to affordable beauty products tailored to their needs, and bid farewell to the demeaning practice of begging for Dark and Lovely and so on from friends and relatives living abroad.

Of course, courting the support of black Americans was an important ideological strategy in the early days of the Cuban Revolution. It backfired with some (Eldridge Cleaver wasn’t won round, to put it mildly); but Assata Shakur, the first woman on the FBI’s list of most wanted terrorists, has been quietly living as a political exile on the island for the past thirty years. It is hard to imagine that any meaningful process of repairing diplomatic relations between Cuba and the United States in these post-911 times could proceed without Shakur’s extradition. But what would the handing over by Havana of this famous ‘cause celebre’ of Black Nationalism to the U.S. authorities mean for the Obama legacy? There is always a heavy price to pay for peace. The question that all of us need to ask ourselves, in the wake of Ferguson, is whether this sixty-seven year old black woman, wanted for murder, is likely to get a fair hearing.

In his announcement of the major shift in Washington’s policy for Cuba, Obama referred to the “unique relationship, at once family and foe,” and this is a dynamic that African nations, with their colonial histories and concomitant legacies, know only too well. In that regard, Havana and Washington are finally operating on African time.

January 6, 2015

Historian Terence Ranger is no more

Zimbabwean historian Terence Ranger (1929-2015) is no more. Ranger was central to the historiography of Rhodesian colonialism and a keen observer of post-independent Zimbabwe. In the image above, taken in 1962, Ranger is on the left. At the time he was being deported from Rhodesia. In middle Joshua Nkomo, then leader of the liberation movement ZAPU, and second from the right is Robert Mugabe, who broke away from ZAPU shortly after (1963) to form ZANU. We’re putting together some tributes on Ranger. Watch this space. Meanwhile, browse some of his wide bibliography and this excellent interview with Ranger.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers