Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 369

January 25, 2015

Ongwen on Trial, Perpetrator or Victim?

LRA commander Dominic Ongwen came under the custody of US ‘military advisers’ supporting the African Union Regional Task Force in the Central African Republic (CAR) on 6 January, 2015. He was subsequently transferred to the International Criminal Court (ICC) custody on 17 January, 2015. Between those two dates, many things that we don’t fully know yet happened. But what is clear is that negotiations occurred between CAR, Uganda, the US, the AU and the ICC regarding what to do with Ongwen and how to handle his transfer once it was decided that he would be tried by the ICC. By the time Ongwen boarded the plane heading to The Hague, he has had been in the custody of the Seleka rebels, the US forces, the Ugandan contingent in CAR, the CAR forces, and the ICC, respectively.

Given that Ongwen was captured by (or surrendered himself to) the Seleka rebels, who, in turn, handed him over to US Special Forces in CAR, it is unclear whether the US will pay the Seleka rebels the $5 million reward for the arrest of Ongwen. And interestingly enough, the American “Hague Invasion Act” forbids the US government from assisting the ICC and allows the use of military force to free any American citizen detained by the Court, including raiding the Court in The Hague, if necessary. Let that sink in.

A decade after the ICC opened its investigation in northern Uganda, it is the first time that the Court has laid its hands on a suspect in that conflict. It is alleged that troops under Ongwen’s command are responsible of some of the LRA’s most vicious attacks in northeastern Congo. Specifically, the ICC has charged Ongwen with criminal responsibility for crimes committed in northern Uganda in 2004: three counts of crimes against humanity and four counts of war crimes.

However, one peculiar factor in Ongwen’s case is his former status as a child soldier. At age 10, Ongwen was abducted by the LRA. The Rome Statute, which is the founding document of the ICC, does not provide tools for the prosecution of anyone under 18, which means that Ongwen’s actions as a child soldier cannot be held against him. He will be prosecuted only for crimes he may have committed as an adult.

However, as the Justice and Reconciliation Project has pointed out, “Ongwen is the first known person to be charged with the same crimes of which he is also a victim… [And his] case raises vexing justice questions. How should individual responsibility be addressed in the context of collective victimization? What agency is available to individuals who are raised within a setting of extreme brutality? How can justice be achieved for Ongwen and for the victims of the crimes he committed?” Allow me to insert here the usual disclaimer that Ongwen is presumed innocent.

Uganda had the option of putting Ongwen to trial in Kampala, rather than letting him be tried in The Hague. This would have been in accordance with Article 17 of the Rome Statute on complementarity, especially given that Uganda has equipped itself with institutions such as its International Crimes Division.

It is obvious that Uganda was able to try Ongwen. But was it willing to? Probably not. Museveni could not come out as the one that handed Ongwen to the ICC given his ambiguous stance towards the Court now (having become one of its most virulent critics and calling on African states to leave the Court.) In the end, Ugandan forces announced that Ongwen will be surrendered to the ICC by CAR authorities.

Ongwen is scheduled to make his initial appearance before the ICC today, 26 January, 2015. This initial hearing serves only to identify the suspect, inform him of the charges against him, and set a date for the “confirmation of charges hearing” which may be held several months from now (the prosecutor might need extra time to dust off the LRA dossier that has been dormant for the past few years.) At the confirmation of charges hearing the prosecutor must present sufficient evidence for the case to move to the trial stage. In any case, there is still a long way to go before an international court tries any LRA commander.

January 23, 2015

Digital Archive No. 10 – African Activist Archive

In the U.S., the past few months have showcased the power of social activism in bringing awareness to injustices in the country. Social activism has a deep history in the States; one that is not limited to domestic issues. U.S.-based organizations and individual activists have frequently looked abroad to attempt to impact change in nations beyond our border. Africa has not been beyond this reach, particularly during the eras of decolonization and antiapartheid activism. The African Activist Archive, a project co-sponsored by the African Studies Center and MATRIX: The Center for Humane Arts, Letters and Social Sciences Online at Michigan State University, aims to capture these histories.

The African Activist Archive is an online archive of “50 years of activist organizing in the United States in solidarity with African struggled against colonialism, apartheid, and injustice.” The creators of African Activist Archive refer to this project as a “people’s archive”; this is a fair label for this initiative as the materials included not only focus on activist organizing by local organizations, but also due to the fact that a good chunk of these materials were donated by individual activists. In a piece entitled “Posters That Challenged Apartheid” posted to this site following Nelson Mandela’s death in December 2013, Christine Root and Richard Knight (both members of the Advisory Committee as well as being major activists in their own right) explained the depth of the African Activist collection, as well as its grassroots origins.

The African Activist Archive is an online archive of “50 years of activist organizing in the United States in solidarity with African struggled against colonialism, apartheid, and injustice.” The creators of African Activist Archive refer to this project as a “people’s archive”; this is a fair label for this initiative as the materials included not only focus on activist organizing by local organizations, but also due to the fact that a good chunk of these materials were donated by individual activists. In a piece entitled “Posters That Challenged Apartheid” posted to this site following Nelson Mandela’s death in December 2013, Christine Root and Richard Knight (both members of the Advisory Committee as well as being major activists in their own right) explained the depth of the African Activist collection, as well as its grassroots origins.

The African Activist Archive Project website contains more than 7,200 freely accessible documents, photographs, buttons, T-shirts, posters, and video and audio recordings from the African solidarity movement from the 1950s to the 1990s. We thank the more than 90 activists who have contributed materials to this collection. We have been adding about 1,200 items per year, and we are eager to hear from people who have kept materials from this struggle.

The collaborative nature of this archive, being gathered from individual activists and organizations, as well as being sourced from various archives around the world, captures a rich geographic and thematic focus. You can navigate the collection through a variety of categories, from the media type to the African nation referenced to the organization which produced the material (both inside and outside the US). Root and Knight provided a great sampling of the posters available on the site in their previous post, so below are a few examples of the other materials captured in the collection.

African Activist ArchiveAfrican Activist ArchiveAfrican Activist ArchiveAfrican Activist ArchiveAfrican Activist ArchiveAfrican Activist Archive

It’s hard to describe the width and breadth of this collection, let alone it’s potential utility for research. While I am a historian of South Africa and Africa more generally, I can only grasp a fraction of the potential that this archive holds for unlocking more stories of decolonization, the antiapartheid movement, and international social justice efforts. Each person who uses this site will discover something different. But taking the time to explore and discover in this rich resource will, undoubtedly, reap rewards. Users interested in delving into the anti-apartheid movement will find the Related Sites list interesting. This extensive list of digital initiatives, museum websites, films, and archives provides a great jumping off point for further exploration into these compelling histories. For those scholars and researchers who might want to go a step further than that, the Archives list offers further pathways for exploring the rich history of the global African activist networks.

Keep up with all of the latest from African Activist Archive on Facebook. If you have or know of anyone who has materials that would fit this unique archive, see the Collection Policy for more information.

As always, feel free to send me suggestions in the comments or via Twitter of sites you might like to see covered in future editions of The Digital Archive! We’ve been getting some good suggestions from readers that will be reviewed soon!

The Triptych: On the personal stories of three of contemporary art’s freshest black voices

Ever wonder what inspires an artist to paste red-lipped Cheshire cat grins over the mouths of white men and women hanging black people in a photograph depicting a commonplace lynching scene from the Jim Crow South?

In the first episode of Terrance Nance’s new documentary The Triptych, premiering this week on U.S. public television, multi-media artist Sanford Biggers talks about some of the thinking behind the creation of pieces like Cheshire (2009):

“Cheshire is a double-entendre,” Biggers explains to the camera, donning a red clown nose. “At once, Lewis Carroll’s infamous cat and the grin of the blackface minstrelsy. Combining the two,” Biggers argues with the acumen of a cultural historian, “makes us re-examine the innocence of our childhood and our sinister histories.”

Much like Biggers does with Cheshire, The Triptych blends varying styles of telling history on screen with art gallery didactics to illuminate the lives, inspirations, and personal stories of three of contemporary art’s freshest black voices today: Sanford Biggers, Barron Claiborne, and Wangechi Mutu.

A work of art in and of itself, The Triptych features the three artists individually, in separate 25-minute episodes.

Lovers of Hip Hop will remember Barron Claiborne’s iconic photograph of Christopher Wallace (a.k.a. The Notorious B.I.G.) sporting a fake gold crown on the cover of Rolling Stone in 2012. Naming his mother as a great inspiration, Claiborne, a self-taught photographer, much prefers to highlight women in his stunning portraits.

“Kids follow their mothers for the first years of their lives,” Claiborne explains from the passenger’s seat of a car crossing the Brooklyn Bridge. “My mother is the one who gave me a camera. My mother is directly responsible for my career!”

Family photographs from the artists’ personal archives like the ones of Claiborne’s mom are a central feature in The Triptych. In fact, each episode devotes a significant amount of time to how each artist’s upbringing inspires them.

Brooklyn-based multi-media artist Wangechi Mutu pays homage to her mother and grandmother in Kenya in pieces like Tree Huggers (2010), which captures the Afro-futuristic quality of her artwork.

“I’m named after my grandmother; she’s named after hers,” Mutu explains from her studio in NYC. “We [the Gikuyu in Kenya] reincarnate through our names to ensure that no one will ever disappear.”

Skeptical of role Christianity played historically amongst the elders in Gikuyuland, Mutu invokes Gikuyu spirituality in the recent Nguva na Nyoka (Sirens and Serpents) exhibition at the Victoria Miro Gallery in London. The Triptych is a special treat for followers of Mutu. Her episode reveals preliminary footage from the film Nguva, which Mutu then re-mastered for the December 2014 exhibition in London.

In fact, re-mastering and re-working history and identity through artistic practice is perhaps the theme most common to each episode. And in so doing The Triptych fits squarely within recent explorations into the function of aesthetics in academic departments like History in post-colonial universities.

The Triptych is particularly fascinating for historians because it places multi-media artists like Sanford Biggers alongside scholarship that blends history and literature. “I think history is about projection,” Biggers postulates. “So why not rewrite history in your own terms?”

Much like some of the most imaginative historians today, The Triptych masterfully meddles with the divide between art and history to give a much richer picture of the contemporary artists it profiles. It is a must-see for lovers of contemporary art and cultural historians alike.

January 22, 2015

How decisive is ethnicity and regionalism in Zambian electoral politics?

Results from Zambia’s presidential by-election held on 20th January 2015 are now clear. They do show a very disturbing trend of regionalism in the voting pattern. Since 1964, Zambia has prided itself as a beacon of unity in Southern Africa. Immediately after its founding, Zambia’s first President Kenneth Kaunda (KK) coined the One Zambia One Nation motto as a way to encourage unity and national harmony. In Zambia, over 70 tribes have to co-exist. The One Zambia One Nation motto however has faced its own challenges. For example, there is some disagreement about the extent to which Zambian tribes actually united at independence. Barely two years into independence, Kaunda was quite shocked to find that the nation he thought had put tribal division behind was actually quite divided along tribal lines. In the ruling party’s convention in 1968, an alliance of Bembas (from North) and Tongas (from South) combined to defeat an alliance of Nyanja (East) and Lozi (West) politicians. Realizing that Zambia was in fact quite tribal in its politics, Kaunda went on a very ambitious project to do what he termed as “tribal” balancing. By this, Zambian tribes were going to share political and government positions. At the core of this “tribal balancing” project was Kaunda’s own personal ambiguity as to which “tribe” he belonged. KK was the son of a Christian Tumbuka missionary who migrated from modern day Malawi to settle among the Bembas in Chinsali. However, during the struggle for independence KK presented himself as a Bemba from Chinsali. The Chinsali Bembas nevertheless still had suspicions of his heritage. Kaunda, in spite of some suspicions, was somewhat regarded as a uniting figure among his peers. This helped to have him cement himself as a trans-tribal leader uniting the new nation.

During Kaunda’s long 27-year reign, he followed this tribal balancing mantra to the core. However, in 1991 Kaunda lost power to Frederick Chiluba. Chiluba’s MMD party abandoned the “tribal balancing” cliché and instead emphasized “merit” as the new standard for government leadership. It was rather surprising though that in Chiluba’s government most appointments in government and parastatal companies went to mostly Bemba-speaking citizens. Merit perhaps meant being Bemba. Chiluba’s leadership was characterized by privatization and liberalisation of Zambia’s economy. The IMF’s structural adjustment program meant that ordinary Zambians were going to pay more for goods and services. After Chiluba’s second term in 1996, a new party emerged known as the United Party for National Development (UPND). Anderson Mazoka, a southerner, led this UPND. The UPND grew very quickly and soon commanded a huge following among southerners. In the 2001 elections, Mazoka lost by a very small margin to Levy Mwanawasa, the ruling MMD’s candidate. Mwanawasa was Lenje, which together with the Tongas are known as the Bantu Botatwe grouping. They are some form of a tribal alliance. Nevertheless, this bitter electoral defeat for Mazoka seemed to have cemented the UPND as a party carrying the aspirations of the people of Southern Province. Levy took no time to brand UPND as “tribal”. It is this “tribal” sentiment that seems to have stuck to the UPND to date.

After the passing of Mazoka in 2006, the Tonga block of the UPND sidestepped Mazoka’s deputy Sakwiba Sikota to choose Hakainde Hachilema as its leader. The choice of Hakainde, a Tonga, instead of Sikota, a Lozi, provoked more suspicions that the UPND was indeed a Tonga-tribal party. Hakainde has led the UPND into three elections since 2006. The latest being the one just ended where he has almost certainly lost to Edgar Lungu, the ruling PF party’s candidate.

The ruling Patriotic Front was formed by one of President Chiluba’s close confidantes, Michael Sata. Sata’s motivation for the formation of the PF was to protest Chiluba’s decision to “anoint” Levy Mwanawasa as the MMD’s presidential candidate in the 2002 presidential poll. A populist speaker, his party grew rapidly to overtake the UPND as a formidable opposition. After losing the 2001, 2006 and 2008 presidential elections, Sata handsomely beat incumbent Rupiah Banda in 2011. The PF party started as a populist party feeding off urban discontentment with the ruling MMD. It, however, grew to overtake the MMD in the Bemba speaking areas (In Northern Zambia). Sata himself never apologized about his party’s Bemba appeal. It was this combination of Bemba votes and the urban vote that was decisive in handling him the victory in 2011. After winning, Sata’s cabinet comprised of 90% Northerners most of whom were related to him in one-way or another. This entrenched the view that the PF was in fact a Bemba-tribal party. While the MMD, during its rule, was widely regarded as a “national” party, its successor, the PF was regarded by some to be a “regional-Bemba” party. Interestingly, the same was said of the opposition UPND since it had a huge Tonga (Southern) base.

After the death of Michael Sata in November 2014, the two major parties fighting for the presidency both had the reputation of being “tribal”. But the PF adopted Edgar Lungu an Easterner and quickly shed off the “tribal” tag. They then began to emphasize their national appeal as a uniting trans-tribal party. The PF then contrasted themselves with the UPND and campaigned against the UPND on the basis that it was a Tonga-tribal party. The consequences of such campaigns seem to suggest something disturbing for the January 20 2015 elections. For the first time in history, Zambia’s east and Zambia’s west are divided on their choice for the presidency. The East (that is Nyanja and Bemba areas) has gone with the Patriotic Front while the West (Tonga, Lozi etc) has voted overwhelmingly for the United Party for National Development. For now this leaves the urban areas as the swing vote. In 2015, this swing vote has gone for Edgar Lungu. It is likely to swing to the UPND in the next elections in 2016. The new president will have the burden to try and bridge this East and West divide. Perhaps coming up with Kaunda’s “tribal balancing” idea could work well for Zambia. Zambians want a country united by the One Zambia One Nation motto, but in order to build a nation in unity, they must deal with the regional divisions that have erupted in this year’s presidential election.

5 Questions for a Filmmaker–Branwen Okpako

Gender and African-Diasporic identity in Germany are recurring themes in Lagos-born, Nigerian/Welsh filmmaker, video artist, theatre writer/director and professor, Branwen Okpako’s work. After studying political science at Bristol University and filmmaking at the Berlin Film Academy, the multifaceted artist has been living in Germany where she has made a number of films. Among them are The Education of Auma Obama – an intimate portrait of her friend from school; feminist, activist and Obama’s older sister Dr. Auma Obama. The film won Okpako several awards, including the prize for Best Diaspora Documentary at the 2012 African Movie Academy Awards. For her first documentary Dirt for Dinner, about the first black policeman in East Germany, she won the German Next-Generation-First-Steps Award for Best Documentary Film in 2000, among other awards. Her feature Valley of the Innocent premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival in 2003. Branwen Okpako’s latest film, the docu-drama The Curse of Medea, premiered at the Berlin International Film Festival in 2014.

Okpako lectures at universities and film schools across the world and is currently visiting Associate Professor of Film at Hampshire College in Amherst, Massachusetts.

1) What is your first film memory?

I used to watch my Dad present his TV show on NTA Ibadan called A Matter of Conscience. He would interview people about the ethical questions of the day. It wasn’t a film but it made me know that broadcast media belonged to us somehow and we had the right to be present. It also taught me that media was indeed a matter of conscience.

2) Why did you decide to become a filmmaker?

I always loved painting pictures, particularly portraits. That’s what I do now with film. I want to show people as they see themselves but in a way that others can recognise themselves as well. I enjoy directing actors and I love to tell stories. Film does all that and because of montage and the temporal nature of the medium, it adds music and poetry. Making films satisfies my soul.

3) Which film do you wish you had made and why?

I am looking forward to what I will make next. I can’t wish to have made someone else’s film that doesn’t make sense. You don’t wish to have given birth to someone else’s child. I love my films and those of my colleagues too. Having said that, there are films that inspire me and give me energy for my profession. gave me that feeling with his last flick. I felt like we can start to do something completely different with film now. The grip of the Hegelian dialectic is finally broken. I feel I have been chewing that fist with my work as well.

4) Name one of the films on your top-5 list and the reason why it is there.

Well I have just mentioned Steves film 12 Years a Slave. I also love ’s films especially Camp de Thiaroye. He is a master counter narrator, such a cool stylish and incisive storyteller and teacher. I love the films of the colleagues of my generation as well; Akin Omotoso‘s control of drama and comedy by turns. Andrew Dosunmu brings the poetry and grace. Tsitsi Dangaremgba whose film Mothers Day was like fresh pepper soup after too many beers. And Khalo Matabane, who can dance with all the devils and still get his message across to God.

5) Ask yourself any question you think I should have asked and answer it.

When are you coming to Johannesburg to show your films about Christopher Okigbo – The Pilot and the Passenger and Christa Wolf – The Curse of Medea?

Whenever you invite me Katarina!

January 20, 2015

Singer Jojo Abot Speaks the Heart’s Burdens Through Music

In a world dominated by social injustice, it’s uplifting to find someone whose creative essence is dedicated to the pursuit of love. Such is the ambition of Ghanaian singer Jojo Abot. Singing in Ewe and English on her upcoming EP, Fyfya Woto, Jojo interrogates the complexities of love and culture through her lyrics and the visuals in her conceptual short films.

Forged on a journey that has taken her through Brooklyn, Copenhagen, Accra and back, the singles from the Fyfya Woto EP represent a sonic expansion of Jojo’s signature electro-jazz style, infusing cosmic synth, reggae and afrobeat rhythms into the mix. Vocally, Jojo is as dynamic and powerful as ever on her new tracks, demonstrating an enviable degree of range and control. Of her sound she says,

“I’ve always loved all things spiritual, hypnotic and electronic fused with familiar traditional acoustic melodies and rhythms I grew up listening to as a Ghanaian child. I’ve always found strength in my femininity and identity as both a woman and a Ghanaian (of Anlo ancestry). My music is simply a reflection of those key elements which largely serve as a basis for my life experience.”

The title of the EP, Fyfya Woto, meaning, “it has just been invented,” is based on the middle name of Jojo’s grandmother. It’s an ode to her grandmother’s bold nature and an allusion to what she describes as the feminine strength each woman can discover within herself. About the forthcoming EP Jojo says,

“Fyfya Woto celebrates and identifies the defiant spirit of every woman. We find fragments of her in us. Even in the face of the consequences of forbidden love, she cries for justice, mercy and equality. She defies the laws of the land based on something pure… LOVE.”

This courageous, love-driven defiance is a theme Jojo visits often, revealing the complex relationship between tradition and individuality in her songs. From the playful “To Li” to the sorrowful “Le Le Le” to newly minted and extra funky “Stop the Violence (S.T.V.),” Jojo confronts struggle with her gift – speaking burdens of the heart through music. Check out her recently released tracks and performances and keep a keen eye on the lookout for the Fyfya Woto EP to be released later this year.

January 19, 2015

Achille Mbembe on How the Ebola Crisis Exposes Africa’s Dependency on the West

In addition to the human toll, the Ebola crisis in West Africa has severe political consequences. According to Achille Mbembe, Western states present their intervention in West Africa as a purely humanitarian endeavor, but it has political implications. At a time when African states attempt to reconfirm their autonomy and responsibility over their own affairs, the West’s actions instead highlight the limits to African autonomy. On the occasion of the translation of Mbembe’s new book, Critique de la raison nègre, into German, the German newspaper Die Zeit interviewed the Cameroonian scholar about his views on the involvement of Western countries in tackling the crisis in states affected by Ebola. We want to point you to a couple of passages worth reading.

One of Mbembe’s main criticisms of the current discourse is its de-politicization of foreign (humanitarian) aid:

Mbembe: The discussion about Ebola is currently being conducted in purely medical and epidemiological terms. It also lets Africa’s political autonomy and cultural diversity fall under the table. The continent is currently on the rise: Africans want to finally overcome their victim status, they want to reinvent themselves as free people and prove to be responsible. Africa is about to show the world the new face of an African modernity. The victory over apartheid in 1994 was a milestone achievement—a victory that Africans achieved on their own. Any intervention that comes from the outside, whether it is military or civilian, provides evidence that Africans are not able to solve their own problems.

Mbembe does not promote an end to all interventions, but aims to highlight that they have “unpleasant” side effects and unveil racist attitudes, as the political history of the continent demonstrates. They present an old question in a new guise:

Mbembe: I mean the old question of the 19th century, which occupies the Western world (the region that traded for centuries with millions of blacks as slaves) since Alexis de Tocqueville: whether Africans can govern themselves. This question often superimposes itself on the realistic perception of the continent, on which—as everywhere else—rational actors act; only that in Africa they do so under post-colonial conditions: [others treat Africans as if] you don’t need to listen to those who cannot govern themselves. They are faceless and voiceless. They are like silly big children. They can’t make political decisions. One of the fatal effects of such interventions from the outside is this impression of immaturity.

Is the Ebola crisis the result of people’s distrust of aid workers? Mbembe responds by pointing to the past to understand the present (a move he makes in his scholarly work, including the new book). The problem is not distrust of aid workers but the structural deficiencies of African countries resulting from slavery, colonial rule and plunder, and decades of civil war. Africans mistrust the general attitude of the West towards Africa, “namely when aid is fiction.” Here he offered of global capitalism more generally:

Mbembe: More money and resources leave the continent than investment and assistance arrive. In the current example, the Liberian hospitals lack gloves that protect against Ebola. How is that possible in a country that has one of the largest rubber deposits in the world? It is dominated by the US company Firestone. Liberia currently exports its raw materials and has no domestic industry that could produce gloves that would now allow the treatment of Ebola patients.

Mbembe thus has an instrumental view of the West’s engagement in African states. Western states rarely intervene for purely humanitarian reasons. The human toll of any crisis does not trigger action by Western governments—only when states are potentially threatened themselves, do they intervene:

Mbembe: Dying alone doesn’t do much. From the West’s perspective, Africa is the continent of millions of inevitable deaths. In Rwanda, the poor Africans have killed each other, as these unfortunate primitives have always done. Hegel said it in an enlightening way: these African societies with their natural primitivism are without history, societies without rationally acting people, far from European modernity and its rational actors. But Ebola is not far away. The virus is mobile, it travels, it is as globalized as the nature of the road. (…) It does not respect borders: This is currently the most worrying for a weak Europe. Therein lies a vital threat to the biological existence of Europe. The borders must be respected.

Ebola thus has dramatic consequences for both the development of the continent and immigration policies in Europe:

Mbembe: My concern is that the continent is now imprisoned by Ebola in a twofold sense: internally due to the closure of borders between African states. And externally, so that Africans do not cross the borders of Europe, whether as refugees, students, entrepreneurs, immigrants or travelers. But there is no development without mobility, without flexibility. Racists of all countries could have never imagined in what ways Ebola would assist them.

*Read the complete interview (in German) here, and a review of Mbembe’s book (in English) here. See also our previous interview with Mbembe on the trope of “Africa Rising.” Translations from German by the author.

January 18, 2015

Why was one of Africa’s greatest athletes forced to strip naked?

Genoveva Añonma, Captain of Equatorial Guinea’s National Women’s Team is a powerhouse on the pitch. Currently playing for FFC Turbine Potsdam in the Bundesliga (for whom she has scored 51 goals in 58 appearances), Añonma was named Africa’s Female Footballer of the Year in 2012. But this week the sensational footballeuse revealed she had been engulfed in a slanderous scandal — accusing her of being a man — that arose after her fantastic performance in the 2008 African Women’s Championships.

In a recent BBC interview, Añonma disclosed that she was subjected to cruel, forced gender testing by the Confederation of African Football (CAF) — the same governing body who later feted her with an award.

A former Mamelodi Sundowns player, Añonma describes how she was made to strip naked in front of CAF and Equatorial Guinea team officials: “I was really upset, my morale was low and I was crying. It was totally humiliating, but over time I have got over it.”

This violating “procedure” not only goes against basic human decency, but it may be contrary to FIFA regulations.

Jiji Dvorak, former Chief Medical Officer at FIFA, stated that gender testing requires a team of experts including a gynecologist or urologist, an endocrinologist, a psychologist and a sports specialist. The athlete is examined in a manner “to protect the dignity and privacy of the individual and also to ensure a level playing field for all players.”

Demanding that Añonma drop her pants at the convenience of CAF officials, isn’t exactly protecting the dignity of a cherished player. Although she pleaded for a proper medical test at a hospital, her request was denied. And she was bullied into a horrific situation of abuse at the hands of CAF officials.

Sadly, she has battled rumours, abuse and accusations for years. Football officials in Germany have categorically denied that she is a man. Marcus Etzel, President of her former club team, Jena, publicly declared: “It’s completely absurd. Of course Genoveva is a woman and we are very happy she plays for us.”

Añonma faces constant criticism because she is an athlete of the highest calibre and targeted because she does not conform. She has maintained that “these accusations come because I am fast and strong, but I know that I am definitely a woman.”

Officials and administrators in football are supposed to be advocates for the beautiful game and for footballers — irrespective of gender. But the treatment of female players with regard to gender testing is deplorable. Officials have no boundaries when it comes to shaming female players. Añonma was awarded African Women Footballer of the Year in 2012 and her male counterpart was Yaya Toure. Unfathomable to think that if there were any pressing medical queries that Yaya Toure would be commanded to strip naked in front of a panel. Women footballers are not the only athletes to be thus treated, there is a history in sport of vulnerability of female athletes to cack-handed gender testing.

Anonma was forced to do so because she is a woman and her dignity was disregarded. It is unfair and unacceptable and also unsurprising. Football is rife with sexism and gender inequality. It is no surprise there is little support from management or officials. Particularly when Sepp Blatter, President of FIFA, is a notoriously cretinous figure who continuously makes ridiculous sexist statements.

A certain amount of misogyny is expected when ridiculous comments from coaches, players and top-officials, to salary inequalities to misogynist practices and violence apologia to even more horrific and violent attacks such as corrective rape of footballers in South Africa are rampant. There are few officials voicing the need for change in football culture.

Football can be an aggressive game and has full contact competition. Women play but are often treated as second-class players despite their achievements. Perhaps officials feel that women can handle the torment and emotional distress of such form of testing. Or it could simply be that they do not respect their female athletes and subject them to horrendous forms of control and power- as in Añonma’s case, gender testing.

Gender testing is not uncommon in football, particularly in cases of exceptional talent in the women’s game.

Last year the Football Federation of the Islamic Republic of Iran (FFIRI) decided it would begin random gender testing by medical teams at football clubs when it was discovered that four players on the women’s national team were transgendered women who had not completed reassignment surgery.

In 2013, Korean superstar Park Eun-Seon was accused of being a man because she scored 19 goals in 22 matches.

Unlike CAF, team officials at Seoul City Amazon refused to further humiliate their player by even addressing the accusations. They insist that it is a conspiracy against the brilliant, androgynous player because she had improved so quickly after a ‘slump’. Eun-Seon had participated in the Olympics, internationally and had already undergone required testing.

Likewise, in Añonma’s career, initially it was suggested that her opponents had “evidence of an inferiority complex” and then accused her. But she was violated nonetheless.

Even after the scandal made international headlines this week, Africa’s Top Female Player of 2012 has not received an apology. Nor will CAF comment on this case. Quelle surprise.

January 16, 2015

Digital Archive No. 9 – The Winterton Collection

I absolutely love photography. This might be obvious from some of the choices I’ve made for previous editions of the Digital Archive, like World War I Africa and Africa Through a Lens. It’s always been a medium that I enjoy on an artistic level but, recently, this interest in photography has trickled over into my academic pursuits as well. This quote from Susan Sontag’s On Photography speaks to the power of photography as a medium to capture snapshots of the past:

“Photographs are a way of imprisoning reality… One can’t possess reality, one can possess images–one can’t possess the present but one can possess the past.”

While, as a historian, I can not pretend to be attempting to possess the past, I can always strive to present the past, an endeavor made much easier through the existence of digital historical photograph collections like the The Humphrey Winterton Collection of East African Photographs: 1860-1960.

A Busoga Railway station, six months after construction was completed in 1912

The Humphrey Winterton Collection is an expansive collection of over 7,500 photographs taken mainly in East Africa between 1860 and 1960. Part of the Melville J. Herskovits Library of African Studies Collection at Northwestern University, the Winterton Collection was assembled by British collector Humphrey Winterton. These photographs preserve a range of key historical moments in the region, from the opening of the Busoga Railway in 1912 to Hermann von Wissman’s 1889-1890 expedition to suppress the Abushiri Revolt. In addition to major historical events, this collection also captures life in this region from the mid-nineteenth- to mid-twentieth century. From portraits to landscapes, this collection really does, as the site purports, represent “an unsurpassed resource for the study of the history of photography in East Africa.” The photographs are tagged and cataloged in a variety of ways, but, to be honest, these efforts at organizing the collection make it quite difficult to find anything. It’s much simpler to use the keyword search function to navigate the collection or, if you have the time, to browse the collection in its totality.

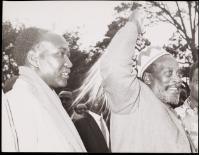

Jomo Kenyatta & Christopher Kiprotech, then member for Kericho East

The site also features an educational collection, entitled “In the Classroom.” Educators will find the Lesson Plan useful to begin teaching students how to engage with not only the items contained in the Winterton collection, but historical photographs more general. The architects of the site have also assembled a series of curated galleries that can serve as jumping off points for learning more about East African women, political leadership, and, even, the Kenyan heritage of President Barack Obama. This section also includes links to some other African historical photograph collections (which I won’t go into detail about here since they might appear in a future edition of The Digital Archive!).

Keep up with all of the latest from the Winterton Collection and the Melville J. Herskovits Library at Northwestern University on Twitter and, as always, feel free to send me suggestions in the comments or via Twitter of sites you might like to see covered in future editions of The Digital Archive!

COMPETITION: What is your favourite Africa Cup of Nations memory?

The best football tournament in the world, the Africa Cup of Nations, starts on Saturday. Forget the Premier League, for the next few weeks, it’s all about what happens in Equatorial Guinea. To get you in the mood, we’ve teamed up with brand new soccer kit supplier AMS (like them on Facebook) to give you the chance to win a Sierra Leone or South Sudan kit. Sadly neither of those teams made it to AFCON, but you’ll still be the envy of all your friends if you get your hands on one of these beautiful, original designs.

To have a chance of winning one of the jerseys, simply choose your favourite moment from any Africa Cup of Nations, describe it, and explain why it was memorable and meaningful for you. It could be a moment of joy, amazement, shock, surprise, fury, glee, schadenfreude, melancholy, or even sadness. The richer and more distinctive your description, the better — we want to learn something about you as well as what happened on the pitch.

Post your entry in the comments under this post, or to our Football is a Country Facebook page. Our editorial team will review all entries, and select the two winners (judges’ decision is final!). As well as getting a shirt, we’ll publish winning entries on Africa is a Country during this year’s tournament. Closing date: midnight GMT, January 23.

We’re also running a Fantasy Football league throughout AFCON — hurry so you don’t miss the first round! Click here to set up your team, and then join our “Africa is a Country Liga”, code 10550350708289.

You’ll notice that AMS aren’t one of the multinational sportswear giants that have traditionally supplied kits to African national teams — Puma, Adidas etc. We caught up with AMS founder Luke Westcott, and asked him to explain a bit more about how AMS got started, what makes it distinctive, and where it’s heading.

“Founded in late 2013, AMS recognised the social, as well as commercial opportunities presented in the hugely popular, yet largely informal football industry in Africa. This recognition came about after traveling to Africa and discovering that the only football apparel available for purchase at a reasonable price were low-quality, counterfeit products. Many of these products were the national team apparel of each respective country we travelled to. This led to the idea of becoming the official national team suppliers, and then providing the respective national football federations with the opportunity to offer their official products to the domestic market, at a price that meet the market demands. This means that fans can purchase official products, featuring cool designs, at a fair price, whilst supporting their national football federation in the process. Furthermore, we also supply the international market through the AMS online store and a few other retailers. This allows us to raise revenue and expand to further countries.

“The main focus we highlight to FA’s as to why they should choose us is the opportunity we provide them to effectively commercialise on the popularity of the national team. Many of the smaller federations never receive revenue from apparel sales, even when they are supplied by major sportswear brands. Many of these brands do not make apparel available for purchase, and if they do, it is often at a price that is way too expensive for most people in the domestic market. Furthermore, all our designs are customised and are created to the specifications of the FA. We never use boring template designs, and always try to design something interesting that will be popular with local fans.”

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers