Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 14

April 14, 2025

In search of Saadia

Tunis, 2021 �� Shreya Parikh.

Tunis, 2021 �� Shreya Parikh. In the many stories I���ve heard about Bou Saadia���whose name translates to ���father of Saadia������he is described as a figure who haunts the medina of Tunis, having gone mad in search of his daughter. He goes from door to door, humming and dancing ���like the Africans do,��� scaring the children on the streets with his black skin, leather clothes covered with cowrie shells, and brusque bodily movements.

According to folklore, Bou Saadia came ���all the way from Africa������the faraway other in the Tunisian imagination���to search for Saadia, who was sold into slavery. No one knows exactly when this mythical figure originated and whether his and Saadia���s stories are based on any recorded historical people. Until 1841, enslaved black women and men were sold in the Souk El Berka in Tunis, where there are shops selling gold jewelry today.

In all the versions of the story I���ve heard, Bou Saadia never finds Saadia. So he continues, to this day, to appear in the street performances during Ramadan, dancing to the rhythms of drums and shekashek, often as a part of mystical rituals known as stambeli. Can we ever bring closure to these strands of stories that are omnipresent in urban legends, in family gossip, and in the novels that circulate all over Tunisia?

The 1846 abolition of slavery by Ahmed Bey, then governor of Tunisia, is often constructed in popular discourse as the ���end��� of slavery. Many Tunisians I meet proudly tell me that ���racism��� ended in Tunisia ���two years earlier than in France,��� where slavery was abolished in 1848. In these conversations, racism, anti-blackness, and slavery are often conflated into one. Slowly, I came to realize that in the Tunisian vernacular language, where many terms to denote blackness are derived from Arabic words for servitude, there is no way to talk about blackness without (indirectly) talking about slavery.

In the region that makes up modern Tunisia, the practice of slavery continued until the early 20th century. While we may know little about the folkloric Saadia herself, the shelves of the National Archives in Tunis abound with traces of enslaved women brought to Tunisia from the Lake Chad region over the 19th century. Many of these women, like Khadija bent Fatma, were forced to work as domestic workers even after the re-abolition of slavery in 1890 under the French colonial rule.

Today, this ���domestic��� nature of black women���s historical servitude is often used to challenge the validity of the term ���slavery��� to name their condition, since slavery has come to be associated, in global imaginations, with the body-breaking exploitation of enslaved people on the plantations of the Americas. Another challenge is the slavery versus post-slavery binary: Does slavery end and become ���post-slavery������that is, a servitude status (and period) assumed to be less dehumanizing than the one preceding it���after the legal abolition of slavery? Or is post-slavery about the degree of servitude rather than the legal act of abolition? If so, and in the absence of testimonies like Saadia���s and Khadija���s, how do we measure this degree of servitude and linked dehumanization that these women underwent? And do we indeed need this measure in order to consider their pain worthy of recognition?

The presence of the traces of the black (ex-)enslaved women and men in the archives���often in colonial administrative documents���does not necessarily imply that the black families in Tunisia who descended from ex-enslaved individuals know the story of their ancestors. One key reason is the taboo linked to slavery. As black Tunisian scholar and activist Maha Abdelhamid has pointed out, family members who may know of the history of enslavement of their ancestors often hide this information, implying that it has been lost over generations.

It was Saadia Mosbah, a black Tunisian activist in her 60s, who brought my attention to the mythical Saadia during one of our earliest conversations in 2020. Mosbah noted that black women are often given auspicious names that bring blessings to their families. Saadia means ���happiness������the kind that brings contentment and joy. While Mosbah had most likely received her name from her family, was that also true for the mythical Saadia? Or had her enslavers (re)named her Saadia, hoping to make her enforced presence a blessing?

Over the years of fighting anti-blackness in Tunisia, Mosbah has herself become a living archive of the stories of suffering and humiliation faced by those racialized as black. Our conversations were often filled with these strands of stories. One way to find closure for the mythical Saadia could be to weave these strands together, extending a myth through pieces of the real.

Maybe, like Mosbah���s ancestors, Saadia had been brought to Tunisia from Mali. And maybe she was sold into slavery in Gab��s, in the south of Tunisia, explaining why Bou Saadia never found her in Tunis. And maybe, after fighting for her manumission, she was forced to inherit her ex-enslaver���s family name and, finding herself without a source of subsistence, worked as a bonded laborer in the homes and the farms of the ex-enslaving family. (One may pause here to ask: Did Saadia���s enslavement end with her manumission?)

Maybe Saadia���s children and grandchildren inherited this bonded servitude and its vicious poverty. And maybe the first great-granddaughter who was sent to school after Tunisia became an independent country ran away from her class when her teacher humiliated her in front of other students, calling her out as the source of the stink in the class, naming her with all the insults that marked her as black, inferior, and ���slave.���

Maybe Saadia���s great-great-granddaughter was the one who fell in love with a passport-less man from Senegal who worked in a local ceramic factory. Maybe, while everyone was celebrating the 2011 revolution that ended the authoritarian rule of then President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, the police arrested and deported this Senegalese man for being an illegal migrant. Maybe this would be the last time that his daughter would see him.

Through the work of black activists like Mosbah, we have learned about the links between historical slavery and contemporary hatred for black migrants. Historically, the stigma of blackness justified a more humiliating treatment for the enslaved black individuals compared to their non-black enslaved peers. Today, in Tunisia, the stigma of blackness justifies a more humiliating treatment of the black migrants compared to their non-black migrant peers, be they Syrian or Italian.

Since Tunisian President Kais Saied���s statement against sub-Saharan migrants in February 2023, state and societal violence against Tunisia���s black migrant population has escalated. In the months following the statement, Saadia Mosbah���one of the key figures campaigning for the rights of these black migrants���became a target of virulent online hatred that called for ridding Tunisia of its black population.

Based on unfounded accusations circulating on social media, Mosbah was arrested on May 6, 2024. As I write these words, she remains in prison. In the meantime, the Tunisian state continues to extend its violent control over the lives of black migrants, arresting and deporting them into the desertic borders with Algeria or selling them to trafficking networks in Libya. As I write these words, it is probable that many black migrant women are living the fate of the mythical Saadia, forced into servitude in locations unknown to their families.

The list of those arrested or forced into exile for showing solidarity with black migrants has grown since the arrest of Mosbah. Despite political threats, many Tunisians and non-Tunisians continue to show solidarity with the black migrants, often organizing material, legal, and medical aid through secure networks. In spite of pending investigations and continued state surveillance, many black Tunisian activists still live and work in Tunisia, calling out the venomous anti-blackness that harms lives, often fatally. Maybe among these brave faces is a descendant of our long-forgotten Saadia, calling for the rights of those like her father, whom she has not seen since his deportation to Senegal, and fighting for the liberation of her ancestor���s namesake.

April 11, 2025

Binti, revisited

Judith Wambura. Image credit Jordan K. Mwaisaka via Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 4.0.

Judith Wambura. Image credit Jordan K. Mwaisaka via Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 4.0. When I was little, I had a very clear image of what it meant to be a grown woman. I imagined owning my own apartment, driving my own car, the ability to do whatever I wanted, whenever I wanted, and an unlimited supply of midriff blouses. This was the epitome of what being a grown, free woman meant to me. So, when I saw Lady Jaydee on the CD cover of her sophomore album, Binti, clad in a black two-piece that showed off her belly button, it immediately resonated with me.

This year marks the 25th anniversary of the career of Tanzanian singer-songwriter Judith Wambura, popularly known as Lady Jaydee. In her 2001 debut album, Machozi, she began carving a lane for herself, building a discography almost exclusively about love and romantic relationships. But the release of her second album in 2003 would firmly situate her as Bongo Flava���s leading lady for years to come.

Binti, as its title suggests, is an ode to young Tanzanian women. The 11-track project of just under 52 minutes, is a compilation of lyrical content that cautioned, encouraged, and confided in an audience of young women working through the growing pains of romantic experiences with men.

Binti���s release coincided with an era of negotiation of sorts when it came to conceptions of womanhood and gender in Tanzania. The early 2000s saw women taking up more space in public spheres, as evidenced by the rise of women in the labour market. There were also more women stars in the art industries, including Jaydee���s peer Rehema Chalamila, popularly known as Ray C, who would release her album Mapenzi Yangu in the same year. The influx of women into public spheres seemed to be a subtle rejection of traditional gender roles that situated them within the private sphere of the home as wives and caretakers. Instead, women, particularly those in urban centres, started pushing against heteronormative boundaries.

Culture productions that acted as a mirror for young people in urban centres reflected this shift in dynamics; newspapers, music and film started to demonstrate the growing tension in romantic relationships between men and women. ���Agony Aunt������figures emerged in newspapers to offer advice to women who had had enough of romantic betrayal or dissatisfaction in their love lives. More films started to portray women���albeit imperfectly���with the romantic agency to start and end relationships as they pleased. And in music, particularly in Bongo Flava, women were publicly declaring their frustration with men through their art.

Jaydee���s Binti joined this chorus of women. The album opener Usiusemee Moyo is a warning to women against feeling too certain of their partner���s intentions, and offers a firm wakeup call to those making excuses for romantic mistreatment as she sings: ���Angeujali moyo wako, asingekuumiza huyo��� (If he cared about your heart, he would not hurt you). In Siri Yangu (My Secret), the listener becomes her confidant as she sings about her own heartache at the hands of past partners. In line with the song title the singer-songwriter refuses to carry the shame of heartbreak and instead makes public emotions often considered to belong in the private sphere.

In the album���s namesake, Binti, she sings, ���Binti amka acha sikitika/ binti amka jikaze anza mwendo,��� (Young woman wake up, stop being sad/ young woman wake up, brace yourself and move forward). Jaydee uses lexical repetition, a technique common in Swahili poetry, such that the track mimics a chant. She encourages women to work toward building a life beyond depending on men: ���kama uko shule vitabu ni juhudi ongeza/ kama mwajiriwa hakikisha cheo umepanda���(if you are in school, increase your effort/ if you are employed, make sure you rise up the ranks).

Siwema, arguably the most successful song on the album, has all the aforementioned themes but instead of addressing women, she directs her lyrics to her love interest. She scornfully confronts him for mistreating her and sardonically declares that his good looks no longer phase her: ���kwahiyo nielewe brother/ sibabaishwi na sura, napenda tabia njema��� (Understand me brother, I���m not rattled by looks, I like good behaviour). She is authoritative and audacious in her tone. A pair of adlibs towards the end of the song, ���usifikiri mimi limbukeni sana��� (don���t think I am very na��ve) and ���ukaniona mimi sugamami wako��� (you thought I was your sugar mummy), hint at the man���s financial dependency as one of a list of infractions.

The closing track, Wanaume kama Mabinti, is a collaboration with rapper turned politician Hamis Mwinjuma, formerly known as Mwana FA. It is a five-minute chiding, framing men���s inability to financially provide and subsequently depend on their partners as not only a failure, but also, womanly. The third verse of Wanaume kama Mabinti is especially illuminating. Jaydee sings; ���hawatoi hata senti, ���yao kulipa bill/ ikifika zamu yao huenda msalani��� (they don���t contribute a cent to the bill/ when it���s their turn they go to the toilet). A few lines later she mocks; ���shoga zangu ebu leteni magauni tuwavishe/ hijabu tuwafunge na vimini, vitopu tuwaazime��� (my friends bring dresses to dress them in/ let���s tie hijabs on them and lend them mini-skirts and tops). The verse reveals that there are consequences for deviating from the gender norm i.e. not being a financially independent man. In the case of the song, the consequence is ridicule.

In her book Borderlands: The New Mestiza/La Frontera, Mexican writer Gloria Anzald��a suggests that while men make up what constitutes gender roles, it is women who transmit these roles. They do so by consistently and continuously performing womanhood following�� the rules set by men such that they become engrained and remain intact. If we use this framework to think about Lady Jaydee���s Binti, we see that there was a clear push and pull between women and gender norms in the early 2000s. While clearly frustrated by men���s treatment of them, women in urban centres were not interested in shifting the gender norms that maintained this imbalanced power dynamic. Some norms, like men being financially independent, were far too essentialist to manhood. Being mocked as ���womanly��� is saying the quiet part out loud: that financial dependency is essential to womanhood.

Ironically,�� the song was met with mostly agreement from audiences and fellow artists alike. Singer-songwriter Bushoke released Mume Bwege, a lament of being mistreated by a woman. Bushoke raises concerns about the woman���s infidelity and her abusive temperament, as well as having to perform household chores. He protests, ���Mwenzenu naosha vyombo, mwenzenu napiga deki/ Mzee mzima napika, jamani nafua nguo.��� (I wash dishes, I mop the floor/ A grown man like me, I cook and wash clothes). The shame in the tone turns the song into a confession. Mume Bwege reinforces the idea that household labour is women���s responsibility and that men should feel ashamed at having to do it. It follows the same logic as Lady Jaydee���s Wanaume kama Mabinti.

By forging her own path in the male-dominated Bongo Flava scene Lady Jaydee was challenging the status quo. However, she was often criticized for straying too far from Tanzanian norms and values. In his paper ���Music and the Regulatory Regimes of Gender and Sexuality in Tanzania,��� Imani Sanga discusses an article released in 2004 in the independent tabloid newspaper Ijumaa, titled ���Lady Jaydee, Ray C kufungiwa kupiga mziki.��� The article suggested that the National Arts Council of Tanzania (BASATA) would ban the two women artists from performing their music as their on-stage style of dress was deemed ���half-naked.��� Sanga reminds us that the term ���half-naked��� is gendered; ������most often in Tanzania when a woman puts on a miniskirt or a blouse that does not cover the whole of her stomach she is considered to be ���half naked.��� This concept is not used when a man, for example, puts on only shorts or takes off his shirt during rap and hip-hop music performance (which is normally the case).���

Lady Jaydee, posing on her CD cover in that black two-piece with her midriff and belly button exposed, was already pushing against gender roles. This norm was (and still is) maintained through state policing of public bodily expression including style of dress. But despite her experiencing the consequence of challenging Tanzanian gender norms, she would go on to use the same language to chide men who did not strictly adhere to their traditionally assigned roles.

Art productions like music, which serve as a cultural mirror of sorts, can play the role of challenging or maintaining the rules we live by. Lady Jaydee exposed the tension that women felt between attitudinal changes around gender on one hand, and the deeply entrenched ideas of what was considered inherent to gender on the other. Binti acted as a mirror, reflecting a key point of contention: despite the desire for a more dignified dynamic between men and women, many young Tanzanians view certain gender norms in a far too essentialist manner to be subverted. Despite the discomfort, Binti reveals that many women were not interested in challenging the heteronormative dynamics that were at the root of their frustration.

April 10, 2025

Tariffs, Trump, and the Global South

Southampton, Hampshire, UK, 2019. Image �� Amani A via Shutterstock.

Southampton, Hampshire, UK, 2019. Image �� Amani A via Shutterstock. As of April 9, 2025, US President Donald Trump announced a 90-day pause on higher tariffs for over 75 countries, reducing them to a baseline 10% rate, while excluding China, which now faces a sharply increased tariff of 125%. This pause, set to expire on July 4, 2025, offers a temporary reprieve for many nations, allowing for negotiations and potentially stabilizing global markets, although the long-term implications and outcomes remain uncertain.

���Liberation Day��� was how US President Donald Trump described it as he gleefully waved a bill introducing sweeping tariffs against his country���s global trading partners. ���Taxpayers have been ripped off for more than 50 years,��� he added, characterizing himself as America���s solemn defender. ���But it is not going to happen anymore.��� Despite widespread attempts to explain to Trump that it is American consumers who will have to absorb the cost of these new measures, the President has resolutely pressed ahead. One EU official said it is more an ���inflation day��� than a ���liberation day.��� Trump���s goal is ostensibly to restore manufacturing to the US, but as pointed out by the celebrated South Korean economist Ha-Joon Chang, you need a strategy to build an industry, not just punitive taxes for companies that want to sell things in your market. In just a few days, the tariffs have triggered instability in global stocks and sent the dollar plunging.

The measure has been met with widespread criticism from both friends and foes alike, neither of whom has been spared. David Lammy, the UK foreign secretary, suggested that Trump���s policy has taken the US back a century. The French President, Emmanuel Macron, described the tariffs as ���brutal and unfounded.��� Beijing, which exports a large number of goods to the US and faces a 104% tariff, warned that there would be no winners in a trade war and called on the US to stop ���unilateral bullying.���

Even the world���s most important financial papers haven���t spared Trump. The Financial Times called it an ���astonishing act of self-harm,��� while the Wall Street Journal said the only real winner would be China���s leader, Xi Jinping, describing the tariffs as a ���strategic gift.���

In Africa, the picture is somewhat more complex. Most countries have been hit with the lower end of the tariff spectrum, facing a 10% levy, but the highest have been borne by Lesotho (50%), Madagascar (47%), Mauritius (40%), and Botswana (38%). The measures also imperil the US���s existing preferential trade arrangements with select African countries through the African Growth and Opportunity Act (Agoa), which allows them to export goods to the US market on favorable terms. However, energy imports and key commodities have been exempted, which are Africa���s main contributions to the global economy. Agriculture has been more mixed.

Theoretically, that should shield these countries from the impact of these measures, but it isn���t that clear, argues Aboulaye Ndiaye, a professor at New York University, Stern School of Business. Ndiaye, a former US Federal Reserve economist, speaks to Geeska about the impact he expects the tariffs will have, what African countries can do to mitigate them, and why we need to rekindle more organic trade routes that can help support intra-African trade.

Faisal AliWhen I went through the list of tariffs on Africa, I wondered whether it would have any impact on the continent, given that the US introduced exemptions on a long list of metals, oil, and gas���Africa���s primary exports. Libya, for example, got 31% but only really exports oil. Are we being too complacent if we say that the impact on African trade, for the most part, is somewhat exaggerated at this stage?

Abdoulaye NdiayeThat is a great question. So, if we look at it by looking at each country and say their primary exports are not affected, so that the practical impact is limited, that would definitely be a risky view. So, yes, it is likely that the immediate impact might not be that large in many places, but there will be secondary impacts because we face the world, and it will respond and retaliate, as we���re in a global trade war now. We know, for example, that stock markets are affected, and when capital gets scarce, Africa is one of the places where people pull the trigger first. There are also large oil exporters, like Angola, Nigeria, and Algeria, who rely a lot on oil, so the drop in global oil prices will have an impact on their businesses and budgets. But even this will help others who are energy importers���like Kenya and even Senegal.

As Africans, we need to think about how we will align and what our responses will be.

Faisal AliTrump is basically complaining that the US has a negative trade balance with many countries around the world, which is one of the things he believes these tariffs will remedy. This means most of us sell more stuff to Americans than we buy and he thinks that is linked to the punitive tariffs many countries have on American goods. Will this help the US rebalance its trade with its African partners?

Abdoulaye NdiayeIt���s like me going to my barber with whom I have a negative trade balance because I basically import a service from him. And if, someday, I wanted to have a positive trade balance, I would add a tax on him cutting my hair and try to begin cutting his. That logic basically doesn���t make sense. So, the bottom line is we need to think about the long-term impact here. And I don���t mean a few months, but over the course of years. We shouldn���t take too drastic measures then, but we do need to seek alternatives.

Faisal AliMost African countries also carry out the majority of their trade with China today, not the US. I think there are a handful of exceptions where the US is the main trade partner. But how much will that dampen the impact of these tariffs in your view across the continent?

Abdoulaye NdiayeIt will dampen the impact because it means they���ve diversified their trade partners, but they need to go further. Some commentators are now thinking about how we will do more trade among ourselves���among Africans, I mean���and increase intra-African trade. But we need to negotiate more bilateral trade agreements, country-specific ones, inside and outside Africa to help explore more alternatives. This includes the US, so they need to pick up the phone.

Faisal AliTwo countries have managed to avoid the tariffs altogether. Those being Somalia and Burkina Faso. Why were they able to dodge this bullet?

Abdoulaye NdiayeWell, do you know which other country managed to dodge this? Russia. Most people got at least 10%. So, I think part of it is that these countries don���t have that large a trade volume with the US.

Faisal AliLesotho was flagged as a country facing a huge challenge because of Trump’s measure. They face a 50% tariff on a sector that accounts for around 20% of their trade. The country’s trade minister, Mokhethi Shelile, has said he’s worried about job loss and factory closures. How should other cases like Lesotho, of which there aren’t many, deal with this problem?

Abdoulaye NdiayeFor Lesotho 50% is huge. Factory closures are a major concern. But let me give an example from the first Trump term, where there was a trade war. Many Chinese companies just took their machines and factories from China, unscrewed everything, moved their equipment to Vietnam, where there were lower tariffs, and continued exporting to the US. Right? So, there are alternatives for these companies, they can shift their production. Lesotho, and countries like it, can also consider third countries where they might reroute their production.

Overall, the major concern for me is the cumulative impact of these tariffs and their repercussions at a time when the US has also cut foreign aid to African countries. The budgets of these countries are quite strained, and it is difficult for them to raise money through private markets. These are the vulnerabilities, cumulatively, that are currently the most challenging.

Faisal AliIntra-African trade has long been a challenge across the continent. Almost all countries, with a few exceptions of those that export to South Africa, have extra-continental trade partners. Some efforts have been made in this regard, such as a continent-wide free trade area and regional free trade blocs like the East African Community. Why haven���t these efforts moved forward more quickly and altered the trade structure for African economies?

Abdoulaye NdiayeAs you���ve pointed out, there have been some ambitious initiatives. You have the East African bloc, the West African bloc, and the Southern African bloc, and they all have their own trade agreements. And now, you have the African Continental Free Trade Area. But, unfortunately, these are all paper tigers. They don���t contribute much. There are still many barriers to trade. The infrastructure that facilitates it isn���t well developed, there are cumbersome customs procedures, regulations are not consistent, and finally, there is still considerable political resistance to further integration.

We need a better understanding of history over its long dur��e to solve some of these issues, instead of just thinking about ourselves in terms of colonization or post-colonization. If we look at the trade agreements that make the most sense for African countries they are not the ones that have been constructed over the last 60 years in the postcolonial period. Rather, you would see more natural links. For example, me having this conversation with you, I���m from Senegal and you���re from Somalia���the link is closer than you think. Take Saudi Arabia, which is an important trade partner for your country; that path is also a well-travelled one for West Africans, like Mansa Musa, the most famous, who went from Mali to Hajj. There were many trans-Saharan and trans-Sahelian trade routes.

I don���t know if you���ve seen the film Io Capitano, which depicts this. It���s a movie about migration but it isn���t just a film showing people leaving Africa and arriving in Europe, it also shows the path. They go from Dakar in Senegal, passing through Mali, Niger, N���Djamena and end up in Libya where they face many difficulties. So all these parts of the world have become embroiled in terrorism and conflict, but if you look at the longer history, this path was one that was rich with trade and exchange, which was organic trade, that has been well-documented by historians. The point I���m making here is that if we apply the economic concept of persistence, which considers how existing patterns tend to become endogenous, these blocs we now have are not really grounded in these longer, more persistent patterns, these trade paths that have existed for years. People have traded gold, salt, and other things from the shores of Senegal along these migration routes, north to the Mediterranean and across the Sahel to the Red Sea.

The geographies where African affinities and trade patterns lie are different from these blocs we���ve established based on language and other considerations. These longer historical trade paths need more infrastructure and other things to support them and we need to re-think that.

April 9, 2025

Journey through the afterlives of a colonized Africa

L��opoldville/Kinshasa 1960. Image credit Mary Gillham via The Mary Gillham Archive Project on Flickr CC BY 2.0.

L��opoldville/Kinshasa 1960. Image credit Mary Gillham via The Mary Gillham Archive Project on Flickr CC BY 2.0. Most of us will never know the dangers of boarding a 1960s commercial airplane from L��opoldville to Rome with a secret document���an article that would change the future of an entire country���s independence���tucked in the rolls of a chignon bun. Such a task could only have been assigned to someone once called the ���Most Dangerous Woman in Africa,��� ���The Black Pasionaria,��� or ���the Woman Behind Lumumba.���

In My Country, Africa: Autobiography of the Black Pasionaria, recently republished by Verso Books, Andr��e Blouin, the activist and former chief of protocol in Patrice Lumumba���s government, reintroduces herself to the world on her terms while taking readers on an intimate ���Africa Tour.��� Originally published in 1983, Blouin���s autobiography is a hauntingly sincere recollection of her childhood and how she became a key figure within the pan-African decolonial movement. It offers an intensely intimate look into politics, defying the dominant male prism that has long defined the independence era���s historical record.

Childhood sets the stage for all coming-of-age stories. In his famous play Incendies, Lebanese playwright Wajdi Mouawad aptly describes childhood as ���un couteau plant�� dans la gorge��� (a knife stuck in the throat). The life of Andr��e Blouin is no exception: Her autobiography contains all the elements of a true coming-of-age story, in which her own growing pains are entangled with those of the movements that awakened her. This framing not only reminds us of the stripped innocence that shaped generations of young African women affected by racial segregation and patriarchy under colonial rule in French Equatorial Africa, it also underscores how politicized the process of learning is.

Throughout My Country, Africa, Blouin vividly recounts her early life and punctuates these recollections with political observations from her future self. For Blouin, what can now be clearly described as childhood trauma was a consistent feature of her life from inception. She traces the pain���s origins through a tender yet critical engagement with the evolution of her parents��� relationship throughout the book. Her father was a 40-year-old white French man, then an agent of an import-export company whom her mother, the daughter of a powerful chief in the Kouango region of the Oubangui-Chari colony (now Central African Republic), married at the tender age of 13. Blouin explores their separation, remarriages, and enduring affection throughout My Country, Africa. Their relationship provides a unique map of the racial, gendered, and class stratification that governed parental claim during an era in which her father had the absolute legal authority to send Blouin to an orphanage for mixed-race girls.

Blouin���s childhood exposes the cruel contradictions that underpinned French colonial institutions in 1920s Congo-Brazzaville, applying a particular emphasis to the abusive nuns in the St. Joseph of Cluny Convent whose missionary mandate included running an orphanage for m��tisses or ���girls of mixed blood.��� This is where Blouin would grow up from the age of three, against her mother���s will: an environment beset by physically abusive humiliation and starvation at the hands of the nuns, no formal education beyond sewing or Catholic indoctrination, and omnipresent reminders of the impure shame embedded in what she and all the mixed-race girls represented. ���The nuns hid Africa from us,��� Blouin writes with fervor.���They refused it and forbade it, almost as if it were something shameful. And the French they taught us was only enough to eke out a living as a seamstress for white ladies. We had no real access either to Africa or to France.���

Introspective details on how this particular wave of history played out in private are often absent from political accounts, eclipsing the reality of the internal gender dynamics and colorism that existed around and within movement-building circles. As she maps her maturing evolution with love, Blouin lays bare the inner turmoil and painful contradictions that inhabited her as a mixed-race woman whose intimate relationships were governed by harsh social rules, both formal and informal. Blouin unpacks her romances with lovers and husbands���such as Roger Surreys, the Belgian aristocrat and former director of the Belgian Kasai company, Charles Greutz, a French businessman, and mining engineer Andr�� Blouin���with the urgency of a confessional. Each of these personal encounters coincided with a stage in her political coming of age, tying her discovery of her beloved Africa with her blooming sexual identity.

By Blouin���s accounting, she had no choice but to make the tensions, nuances, and difficult compromises of love a part of her analytical framework, starting by reckoning with the generational patterns and attitudinal differences between her and her mother���s views on relationships as having been ���entirely shaped by the usages of colonialism.��� Her intimate contact with white partners throughout the years offered her proximity, protection, and insight into the inner workings of the colonial system; direct access to which very few African women at the time were permitted. The instructive potential of these relationships becomes clear when bravely confronting one���s suffering, as Blouin���s existence as a colonial fantasy demanded. Ultimately, the same racial and sexual politics that bled into both her parents and her own relationships followed Blouin into her organizing career later down the line, where she was often described and shamed by the international press as a ���courtesan of all the African chiefs of state.���

Blouin cannot tell her story without tangentially making observations about�� ���her country, Africa��� interwoven throughout the first sections of the book, with an earnestness and fervor akin to Maryse Cond�����s famed memoir, What Is Africa to Me? Contrary to the nationalist air at the dawn of independence, between a childhood and adulthood split in Brazzaville, Bangui, with travels in between, the world Blouin discovered outside of the orphanage and the terms on which she sought reconnection with it was inherently borderless, tied to her relationship with her mother, yet unfamiliar enough for curiosity. This does not mean it was free from the semi-essentialist gaze in engaging explicitly with Africa as a unitary entity���moments such as her journey down the Congo River with the Belgian director of the Kasai mines evoke a reductive description of Africanness that her work seeks to shed. Her descriptions of the continent are often made through the lens of racial segregation, landscapes, and cultural attitudes and practices, with a few exceptions in the first part of the book (see VY Mudimbe).

The editing and translation of this published version of My Country, Africa by Jean MacKellar has been criticized by Blouin herself, who sought legal action against her for its distortive framing, a nuance echoed by her daughter in the book���s epilogue. As with any coming-of-age story, Blouin���s political mind becomes sharper as she grows and develops a heightened awareness of the historical events occurring abroad, the world order shifting in the background of her own evolution.

Blouin���s transnational exposure to the challenges and successes of bubbling independence movements, without the nationalist or ethnic anchors in her political aspirations, provided her with a birds-eye view unlike many male revolutionaries, whose complicated legacies are often glossed over by their savior status of sainthood. This is at the heart of the second half of the book���beginning in 1958 Guinea and her involvement in the campaign against President De Gaulle���s referendum, through Madagascar, and back to Brazzaville, Oubangui Chari, the Congo, and later Algeria. Amid growing fears of her political engagement from France, multiple assassination attempts, and expulsions, she chronicles her role in promoting political pan-African solidarity while advising the movement leaders shaping the trajectories of their respective countries��� independence. This included fraternizing with certain leaders in opposition to the RDA(Rassemblement D��mocratique Africain, or African Democratic Rally Party), such as the newly elected President of the Central African Republic, Barth��lemy Boganda, despite criticism from her family and others.

Blouin���s politicized anger would find refuge years later following her move with husband Andr�� to Siguiri, Guinea, coinciding with the rise of the RDA co-founded by Guinean leader S��kou Tour��, whom she readily credits for her ���second birth.��� Her career would come full circle after overhearing the Lingala of Antoine Gizenga and Pierre Mulele, members of the Parti Solidaire Africain (PSA) under the Belgian Congo and comrades of Patrice Lumumba.

She was asked to organize the Feminine Movement for African solidarity and politicize the women of Congo during the PSA and MNCs (Congolese National Movement) fight for the country���s independence where she mobilized more than 4,000 women as the Congo crisis loomed. She believed deeply in African women���s inseparable liberation from the continent���s political future, and her initiatives in 1959 Congo marked the first time in history that the political condition of Congolese women was acknowledged. Blouin was later credited with writing part of Lumumba���s independence speech, organized broadcasts on ���African moral rearmament,��� and tirelessly sacrificed while organizing treacherous journeys for the movement across the country.

As she relays intimate details of exchanges between her, Gizenga, Mulele, and Lumumba as the danger of Belgian tactics and political betrayal grew more imminent, Blouin empathetically yet soberly criticizes the frequency of Lumumba���s travels, his naivet�� in the company he kept close, and the tactical softness of his early policies which were clearly leading the country towards an inevitable catastrophe. Despite the damage and pain caused by the colonial system in her life���s journey, the most consistent feature of her political assessment is that the ���mutilated will of the people��� and selfishness of the continent���s elites have been ���our worst enemies��� in the project of establishing sustainable statehood and that this susceptibility may have been lowered if independence was won in the crucible of war:

I see now how ill prepared, morally we were for our new responsibilities��� We often abandoned ourselves to selfish, short-term prizes.�� We have not yet learned the long term, day-to-day faith and application needed in the slow task of building responsible citizenry.

The political lessons to be drawn from Blouin���s life and career are far-reaching and hold painful contemporary resonance, particularly in Congo. The current situation in the Democratic Republic of Congo���s Eastern city of Goma overtaken by Rwanda-backed M23 rebels will be remembered as yet another dark chapter of the country���s history. This time it features the ongoing complicity of�� Western leaders in shredding any remnants of international law, Rwandese state government and allies, and the Congolese political elite���s consistent abdication of responsibility to protect its citizens now under the ���leadership��� of President Felix Tshisikedi.

This moral rearmament will not come about in the DRC by recycling reductionist clich��s as the go-to African poster child for global extractive industry or imperialist criticism. These lessons were harshly learned by Blouin as she came of age and suffered the disillusionment of the epochs��� pitfalls. They remain critical lessons, and their human costs will continue to pile up without a commitment to truth-telling and self-interrogation of our collective personal wounds.

As Amilcar Cabral argues, independence is but a trust-building exercise with stages of scrutiny by a population to ���win material benefits��� that must be continuously earned to exist, and whose ambition cannot be outsourced in perpetuity. In Blouin���s model for the future, she sketches out hope for a people-centered African development model, rooted in autonomy and optimization of human capital.

One can only hope that her vision ultimately becomes a reality.

My Country, Africa: Autobiography of the Black Pasionaria by Andr��e Blouin (2025), is available from Verso Books.

April 8, 2025

Why the far right needs violence

Police repressing protesters in front of the congress in Buenos Aires, 2017. Image �� Fabricio Nicolas Fischer via Shutterstock.

Police repressing protesters in front of the congress in Buenos Aires, 2017. Image �� Fabricio Nicolas Fischer via Shutterstock. Argentina���s President Javier Milei has declared war���not just on the political ���caste,��� but on the very institutions that safeguard public welfare. In just over a year, he has slashed pensions, gutted university budgets, and deployed an anti-protest protocol that legalizes brute force. Despite his campaign promise to wield his economic ���chainsaw��� against the political ���caste,��� the hardest-hit sector has been ���piss-soaked” pensioners (in the President���s own words), accounting for 30.6% of the total budgetary cuts. Far from hiding, Milei embraces a sheer spectacle of repression and cruelty. His version of neoliberalism is unapologetically violent.

And he���s not alone. From Milei���s frantic use of metaphors to Trump���s advertisement of an ethnically cleansed Gaza, a transnational far-right is testing just how much violence the public will tolerate in the name of market ���freedom.��� Across contexts, these leaders promote a model of governance that handcuffs the state of its redistributive functions while clearing the field for the AI-crypto-corporatism to operate freely���at times even promoting its use as an official state policy.

What binds these figures is not just a socially conservative ideology, but also a shared style. The performance of strength, the disdain for complexity, and the scapegoating of selected minorities, constitutes a shift, as labeled by Gareth Watkins, toward ���postmodern conservatism”:

The main effect of this shift has been to enshrine acting like a spoilt fifteen-year-old boy as the organising principle of the reactionary movement (…)���if anything, they believe, the postmodern right needs to become more absurd; it needs to abandon Enlightenment ideals like reason and argumentation altogether.

The abandonment of rationality and its replacement with personal attributions are trademarks of a new form of governance that needs, in turn, to discard checks and balances altogether. This form of governance departs from the soft-spoken language of the 1990s technocracy. Today, it is highly ideologized, distilled of personal mythologies, loud, theatrical, and punitive.

When Milei brags about conducting ���the largest fiscal adjustment in human history,��� he is doing more than announcing policy. He is advertising a new Darwinistic political morality: pain is proof of courage, collapse is a prerequisite for a messianic rebirth, and those left behind are simply unfit for the times.

Austerity is no longer an economic necessity but a moral imperative: To talk about budgets today is to dive into the core of the social contract. The nation is merely another dependent variable in a game where corporate power has a first-mover advantage.

Argentina���s healthcare system makes a good example: One of the first decisions by the self-proclaimed anarcho-capitalist was to deregulate the private healthcare system, which automatically skyrocketed their prices up to 235% in 2024. At the same time, the state-run healthcare system began limiting access to free medication for retirees and closing specialized services, such as AIDS programs and functioning public hospitals.

Cruelty comes as no surprise from a president who openly declared that ���it is wonderful when companies go bankrupt,��� inviting Argentine enterprises to ���adapt��� to his radical economic liberalization agenda or ���perish.��� Milei was referring to the competition between national businesses and US companies that, in his words, ���deliver better goods at a lower price.��� It���s a narrative that pits the weak against the strong���where the weak are not only expected to be eliminated but are seen as deserving of it. There is no acknowledgment of the structural inequalities and precarities that place Argentine companies at a disadvantage���nor of the broader benefits that come from strengthening domestic production, such as job creation, economic stimulation, and strategic development for the country as a whole.

Similarly delusive, by the time Trump gave his inaugural speech claiming that ���the pillars of our society lay broken and seemingly in complete disrepair,��� he was receiving the best socioeconomic inheritance of any elected president since George W. Bush came to power in 2001. The US economy has surpassed other major economies in the post-pandemic period, outpacing pre-pandemic growth forecasts even amid surging prices and aggressive interest rate hikes.

Even so, Trump may be hitting the nail on some shared notion; that American democratic institutions are at an all-time low in terms of credibility. As Aziz Rana puts it, they have:

Allowed Trump to gain office in 2016 without winning the popular vote and then to reconstruct the Supreme Court along lines that were wildly out of step with public opinion. When Trump tried to overturn the election result in 2020, the existing institutions made it exceedingly difficult to impose any sanctions on him, whether through impeachment, prosecution or removal from future ballots.

Around the world, institutions built on informal norms and elite consensus are proving incapable of resisting leaders who don���t pretend to follow etiquette, and in turn expose how susceptible the institutional scaffolding was. After all, how much of stability depended, in fact, on consensus of elites?

In Argentina, this looks like Milei���s sweeping use of executive decrees, including a constitutionally dubious new debt agreement with the IMF. It looks like the criminalization of protest, the attempt to weaken collective bargaining rights, and the targeting of public education. When students and workers protest, they are met with tear gas and rubber bullets. The state does not attempt to conceal violence, rather broadcasts it.

In the US, Trump���s targeting of universities and activists signals a broader ambition: to check the vital signs of democratic institutions. The case of Mahmoud Khalil���a Palestinian activist and green card holder detained without charge has raised several alarms. Many see his case as a test run for suppressing political dissent, especially on university campuses. While Khalil���s detention is being legally contested, it has already signaled that critique of US foreign policy may carry personal risk, particularly among student activists. The irony that this crackdown on speech violates the First Amendment once invoked by conservatives to defend hate speech is irrelevant to a right-wing bloc that no longer bothers with consistency. In Argentina and the US, what is being tested is not just how far these governments can go, but also how elastic the rule of law can become in service of power.

Regardless, any demand for accountability falls on deaf ears as these leaders exercise boundless authority over media, and restrict and criminalize dissent. This infrastructure of repression is not incidental but foundational to corporate governance that treats dissent as an obstacle to market logic.

���Everything that can be privatized will be privatized��� might as well be the global hit of the moment���echoing from Javier Milei���s Casa Rosada to Elon Musk���s declarations near the White House. But the goal isn���t really to shrink the state, it is to genuflect the whole of collective life to market logic.

What remains to be seen is whether the spectacle of strength will continue to seduce those who first brought these figures to power. For now, the message has been made clear: Winner takes all.

April 7, 2025

The bones beneath our feet

Still from Our Land Our Freedom �� 2024.

Still from Our Land Our Freedom �� 2024. The legacies of the past are always our present, and the histories that we are not able to confront continue to play out. This is certainly true in Kenya, where the unfinished business of the Mau Mau war and the injustices of British colonial rule endure.

In Our Land, Our Freedom, Kenyan directors Meena Nanji and Zippy Kimundu follow Evelyn Wanjugu Kimathi as she traces the legacies of her family���s history and confronts the current political injustices that spring from Kenya���s painful colonial past. Filmed over almost a decade, the documentary follows Wanjugu, daughter of famed Kenyan independence fighters Dedan and Mukami Kimathi, as she searches for the remains of her father, who was executed by the British colonial administration in 1957���six years before Kenya gained independence. At its best, Our Land, Our Freedom is a deeply moving portrait of one woman���s tireless struggle to honor the legacy of her father.

As the film���s title suggests, land is central to the narration of this story and to the history of the Mau Mau. Without a doubt, this question is echoed in Kenya���s sociopolitical present. As Wanjugu Kimathi puts it in the film: ���To us, land is a matter of life and death.��� Certainly, land was central to the Mau Mau campaign for independence, whose slogan ithaka na wiathi translates as ���land and freedom,��� or more conceptually as ���self-mastery through land.��� To the Kikuyu people, who made up the vast majority of the Mau Mau movement, land was the way of life; the organizing principle that connected members of the community to each other and to the ancestors. And through all the changes of the last six decades, land alienation is still the central issue that galvanizes Mau Mau veterans.

In the film, Wanjugu visits Kieni, a former colonial village where families were forcibly moved by the colonial regime in the 1950s, as part of the brutal British counterinsurgency efforts. Unable to gain title deeds or to buy land in the post-independence resettlement programs, these families have been living in Kieni as squatters for almost seventy years. They are certainly not the only ones; the patchy post-independence land resettlement programs did find land for tens of thousands, but left many waiting. And even those who did receive land were often unsatisfied with their lot. As a consequence, land poverty was, depressingly, both a cause and a result of the Mau Mau war, since veterans like those at Kieni have been left in the same villagized and alienated manner that caused them to take up arms in the first place. Meanwhile, the political class in Kenya owns vast amounts of land and wealth and sees calls for redistribution as a threat.

Our Land, Our Freedom makes an important link between the plight of Mau Mau veterans in places like Kieni and other struggles for land justice, in particular the Kakuzi land case. Wanjugu���s attempts to ���link struggles��� with communities in Murang���a evicted by the British-owned Kakuzi company highlights the broader question of squatters and land alienation in Kenya, and its roots in colonialism. Ongoing struggles to get justice for human rights violations and the related historical theft of land speak to the reality that the Mau Mau plight is one of a constellation of historical injustices that persist in contemporary Kenya.

In the same month that Our Land, Our Freedom was released, another Kenyan film, The Battle for Laikipia, premiered. This film documents the ongoing tension between white settler ranchers and Samburu pastoralists in Laikipia County. In both films the message is clear: Political independence and justice are not the same thing, and many communities in Kenya are still suffering from the legacies of colonial land grabbing and violence; historical injustices continue to reemerge from their shallow graves, but find little support from Kenya���s political class.

Our Land, Our Freedom���s protagonist, Wanjugu Kimathi, will not be deterred by the political disregard of these justice movements. In 2017, she registered the Dedan Kimathi Foundation, essentially a veterans organization that functions as a land buying co-operative, mobilizing landless people to purchase land collectively. The foundation is a powerful representation both of�� Kimathi���s strength as an organizer and of the power of community organizing to effect material change in the face of political dismissal. By 2018, the Dedan Kimathi Foundation had a resettlement site in Rumuruti, and Wanjugu makes the prudent point that in uniting and resettling these veterans, she has done what four political regimes have failed to do. However, this project is incomplete and shrouded in questions about how the funds have been used, complicating an otherwise neat narrative of a popular hero righting the wrongs of the colonial past. The Dedan Kimathi Foundation has evolved into an environmental organization, with a focus on planting trees.

Midway through the film, Wanjugu finally visits Kamiti Maximum Security Prison to search for Dedan Kimathi���s burial site. Accompanied by a former detainee at Kamiti who thinks he might be able to find the grave using a hand-drawn map, Wanjugu finds that her hope turns to frustration as they end up walking in circles. It would be almost farcical if it wasn���t so tragic, and it directly parallels Mukami and Wanjugu���s visit in 2003 with the same mission in mind. On this occasion, they went with eleven people who showed them twelve different spots, none of which yielded the precious remains of their kin. It is evident here that the search for Dedan Kimathi���s remains is of deep personal significance to the Kimathi family, and has taken on wider political life. However, perhaps it is not just about the literal remains; it is about honoring the legacy of Kenya���s struggle and the immense personal and political costs that Mau Mau fighters have borne.

It is not only Kimathi���s remains that are left in unmarked mass graves; in the opening sequence of the film, Wanjugu Kimathi visits a mass grave in Ndeiya, Kiambu County, the site of a colonial detention camp during the Mau Mau war. They dig a few feet below the ground and find a human skull in a shallow mass grave; this is one of scores of�� mass grave sites across Kenya, where the bodies of Mau Mau fighters and others killed during the war were unceremoniously buried in large unmarked pits. As Wanjugu takes in the horror and violence represented in this mass grave she says, ���I���m seeing as if this is my father, Dedan Kimathi,��� before placing the skull back to be reburied in the shallow grave.

What are we to do with the unidentified bodies that lie in these mass graves? For the past sixty years, the Kenyan government has opted out of taking responsibility for what is, undoubtedly, a deeply sensitive question. What the film conveys very clearly is the link between the neglect of these sites and the Kenyan government���s disregard for the plight of Mau Mau veterans: the lack of care for both the living and the dead. However, it falls short of considering how these anonymous human remains might ask us to reflect on the mass victims of violence, and the related perils of hero worship in the case of a popular uprising. Certainly, it was ordinary people who fought and died in the Mau Mau war, and their remains are surely owed the same care and reverence as those of Dedan Kimathi or any other leader of the movement.

The release of the film was politically timely. It was launched in the wake of the Gen Z protests, where a new wave of young Kenyans took to the streets to protest the injustices of the Kenyan political class. With these popular uprisings of 2024, it is clear that 60 years after independence Kenya is still trying to make sense of her past and her future; we are still negotiating what freedom should look like.

There were boos and jeers during the Nairobi premiere of the film when President William Ruto appeared on screen; here he was giving a speech at Mukami Kimathi���s state funeral in 2023. In this scene, Ruto makes still unfulfilled promises to assure title deeds for people squatting in former colonial villages, and to find Dedan Kimathi���s remains and give him a hero���s burial. Even in death, the Kimathi family are eclipsed by the political leaders who would appropriate their grief for their personal political campaigns.

Such public performances clearly do not fool ordinary Kenyans. Instead, they illustrate that politicians understand the importance of this negotiation with the past and feel, at the very least, a duty to pay lip service to it. Our Land, Our Freedom sends a message to that political class who wants to pacify uprisings with empty promises; it demonstrates that Mau Mau veterans will not just quietly fade away and that a new generation will continue the struggle for justice that their parents and grandparents began.

Wanjugu Kimathi insists that hers is not a political project; but how could it not be? The film documents how her activities attract the attention of people in high places and captures her having several dramatic phone calls with a national intelligence agent who warns her to stay out of politics and to leave the matter of Dedan Kimathi���s remains to the government. What���s more, Wanjugu was briefly arrested in 2018, and it is clear that her work is politically dangerous. As though speaking to this, in a voiceover she asks, ���Is Kimathi a threat in life and in death?���

Above all, Our Land, Our Freedom is a portrait of Evelyn Wanjugu Kimathi, the woman and the activist. Wanjugu is a complicated figure, and, in some ways, the perfect protagonist for such a complex history. Always elegantly dressed and energetic, she commands the screen with her powerful declarations about justice. Born to Dedan Kimathi���s wife Mukami Kimathi in 1972, 15 years after Dedan Kimathi���s execution in 1957, Wanjugu claims to have no connection to her biological father, and she and her mother see her as the daughter of Dedan. While some have questioned this as a kind of fraud, Evelyn���s spiritual connection to Kimathi appears profound and genuine. ���I was born in a freedom fighter’s family,��� she narrates. For her, it is this identity, above all else, that drives her.

Some families find ways to move on from pain and grief through activism, and it is touching to see how Evelyn���s work is spurred on by a deep connection to her parents. The film���s biggest strength is in its intimate portrayal of Wanjugu and the Kimathi family: the tender moments between Evelyn and her mother, Mukami, and with her husband and children milking her cows and tending to the crops at her family���s rural home in Kinangop. These scenes show Wanjugu not only as the tireless champion of the downtrodden Mau Mau survivors but also as a loving daughter fighting to uphold her parents��� legacy and build something better for her own children.

The film spans almost a decade, and the narrative arc forms as it is being filmed. This makes for an exciting, though sometimes chaotic, documentary narrative. At times, the film feels as if it���s trying to do too much, and the stretch weakens what is, perhaps, its biggest strength: an intimate portrait rather than a universal one. It might have been a more digestible film had it resisted the urge to incorporate all the threads of Wanjugu���s work. But perhaps this is part of the point Nanji and Kimundu are trying to make; that this is a complex history and a political reality that does not fit neatly into a single narrative. Ultimately, Our Land, Our Freedom is a timely film with a strong message of justice that is hard to ignore.

April 4, 2025

What comes after liberation?

Joseph Nkatlo, Albie Sachs and Mary Butcher giving the closed fists with upraised thumb salute at a Defiance Campaign meeting at the Drill Hall in Cape Town on 12 April 1952. Photo: National Library of South Africa. All images courtesy of Albie Sachs.��

Joseph Nkatlo, Albie Sachs and Mary Butcher giving the closed fists with upraised thumb salute at a Defiance Campaign meeting at the Drill Hall in Cape Town on 12 April 1952. Photo: National Library of South Africa. All images courtesy of Albie Sachs.�� Born on January 30, 1935, in Johannesburg to Solomon Sachs and Rachel Ginsberg, Albert ���Albie��� Sachs turned 90 in January. Albie moved to Cape Town with his mother and his younger brother when he was three years old. Advanced for his age at school, he skipped two grades and as a result enrolled for his first year of university when he was only 15. His parents were deeply involved in the Garment Workers Union of South Africa, and at a young age he was determined to follow his own path, wherever it led. The rest, as they say, is history.

Graduating with a law degree from UCT, he started practicing as a lawyer at the age of 21. Sachs was in attendance with 2,000 others in 1955 at the Congress of the People in Kliptown, Johannesburg, when the Freedom Charter was adopted. He was arrested in 1963 in Cape Town under the 90-day Detention Without Trial law, and after 90 days, on the pretext of being released, and after being given his clothes and belongings, was rearrested for a further 78 days, thus serving a continuous 168 days in solitary confinement without trial. He wrote about this experience in The Jail Diary of Albie Sachs (1966). He was arrested again three years later in 1966, when he was subjected to sleep deprivation torture. South African Security Branch officers had received training in interrogation techniques in foreign countries, including in France, which was known for having used torture extensively during the Algerian War of Independence. Following this, he was allowed to leave South Africa on the condition that he could never return.

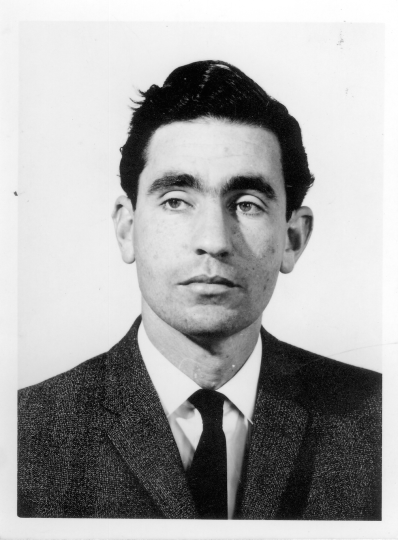

Portrait of Albie the young advocate ��� c.1957. Photographer unknown.

Portrait of Albie the young advocate ��� c.1957. Photographer unknown.Sachs was reunited in England with Stephanie Kemp���a South African anti-apartheid activist who had been arrested and imprisoned at Pretoria Central Prison for blowing up pylons���and whom he married in 1966. They raised two sons, Alan and Michael and divorced in 1980. He obtained a doctorate in law from the University of Sussex in 1970 and lectured at the University of Southampton from 1970 to 1977. Sachs moved to Mozambique in 1977 following the country���s independence from Portugal in 1975. He learnt Portuguese, taking up a post as law professor at the Eduardo Mondlane University in Maputo and later as Director of Research in the Ministry of Justice. Sachs became deeply involved in the art and culture of the country. He maintained strong connections with Mozambique���s leading artists Malangatana Valente Ngwenya and Alberto Mabungulane Chissano and acquired art by numerous local artists during his 11 years in the Southern African country. Sachs donated his Mozambican art collection to the University of Western Cape – Robben Island Mayibuye Archives.

Albie meeting Stephanie Kemp upon her arrival by boat in Southampton, UK – September 1966. Photographer unknown.

Albie meeting Stephanie Kemp upon her arrival by boat in Southampton, UK – September 1966. Photographer unknown.African National Congress (ANC) leader Oliver Tambo called on Sachs to draft the organization���s code of conduct���particularly denouncing torture and advocating just procedures within the organisation���which was adopted by the party in Kabwe, Zambia, in 1985. Victim of a targeted car bomb attack in Maputo in 1988 by the South African Security Forces, Sachs lost his right arm and the sight of his left eye. A passerby was killed in the assassination attempt. Sachs was transferred to London to recover.

Albie presenting the ANC Code of Conduct, which he describes as the most important legal document written in his life, at the African National Congress Consultative Conference in Kabwe, Zambia – June 1985. ANC Photographer.

Albie presenting the ANC Code of Conduct, which he describes as the most important legal document written in his life, at the African National Congress Consultative Conference in Kabwe, Zambia – June 1985. ANC Photographer. Albie getting into the same car that was used in the car bomb assassination attempt – Photo: Sol Carvalho.

Albie getting into the same car that was used in the car bomb assassination attempt – Photo: Sol Carvalho. Albie interviewed in hospital after the bomb ��� 1988. Photographer unknown.

Albie interviewed in hospital after the bomb ��� 1988. Photographer unknown.In 1989 he wrote a paper entitled ���Preparing Ourselves for Freedom��� presented at the ANC conference in Lusaka, which created a huge debate in South Africa among artists and cultural workers. Following Nelson Mandela���s release from prison in 1990 and the unbanning of the ANC and other parties, Sachs returned home to South Africa and was elected on the ANC���s National Executive Committee. He was very involved in the negotiations towards a new political solution and continued working on a draft of the new constitution. In 1994 President Nelson Mandela appointed him a judge at the Constitutional Court.

Albie at the University of Durban Westville in 1991 at the first general meeting at the ANC on home soil. Also pictured are Chris Hani shaking hands with Cheryl Carolus, Jacob Zuma on left and Walter Sisulu on the right. ANC Photographer.

Albie at the University of Durban Westville in 1991 at the first general meeting at the ANC on home soil. Also pictured are Chris Hani shaking hands with Cheryl Carolus, Jacob Zuma on left and Walter Sisulu on the right. ANC Photographer.The former judge is the author of numerous landmark judgments and several non-fiction books. He is the recipient of several international honorary awards, including from the countries of South Africa, France, Portugal, and Brazil, to mention a few. He holds 27 honorary doctorates from many prestigious universities, among them Princeton, Columbia, Cambridge, Dundee, Aberdeen, London, Sussex, Southampton, and locally from the universities of Cape Town, the Western Cape, the Witwatersrand and the Free State.

Riason Naidoo interviewed Albie Sachs in his home in Cape Town.

Riason NaidooYou are quoted as saying that you were surrounded by art and culture as a child. What was it like growing up in your home?

Albie SachsMy mom, Ray Sachs then���she was Ray Ginsberg before and became Ray Edwards later���separated from my dad in Johannesburg, and she brought my little brother and I to Cape Town. She was Moses Kotane���s typist. I grew up hearing my mom saying, ���Tidy up, tidy up. Uncle Moses is coming.��� Uncle Moses being the general secretary of the South African Communist Party. She met Cissie Gool, who invited us to come and stay with them; Gool was living with Sam Kahn in a bungalow in Glen Beach. My childhood was spent in Clifton, where houses there, in those days, were a little grander than shacks, flimsier than houses.

Albie with his mother and younger brother Johnny at Clifton beach in Cape Town, c.1937. Photographer unknown.

Albie with his mother and younger brother Johnny at Clifton beach in Cape Town, c.1937. Photographer unknown.The Communist Party attracted a number of cultural figures. It was big on culture with a capital C. Gregoire Boonzaier, the painter, was a close friend of my mom. The little hanging space we had in the house would have a Boonzaier painting. The image I had of an artist was of a robust, fun-loving person, full of laughter. He was full of stories. Boonzaier had a blue Chevrolet car with a dicky seat at the back, which could open up, and my brother and I would sit in that seat while he was driving around. That was also where he would put his paintings when he was traveling through the Karoo. He became a commercial traveler of his own paintings. He would say, ���A house without a painting is a house without a soul.���

The other figure of influence from my early childhood was Uys Krige, the Afrikaans poet. He lived in Clifton 4 and was married to actress Lydia Lindeque. I remember being told he was a poet. I didn���t understand what a poet was back then. Like Boonzaier, he was also an Afrikaner rebel who had been to Spain, which in those days was a battleground between fascism and democracy.

Some years later I���m at the University of Cape Town. I���m not politically active. I���m making my own way. The theme of modern art puzzled me, and I became fascinated by contemporary art. In my first year of university I would hitchhike from campus down into town to the Groote Kerk Gebou. They had an Afrikaans-owned bookshop called ID Booksellers with beautiful art books. I would sit down and work my way through these art books. Totally astonished at first���the odd colors, the meaningless shapes, the terms and movements slowly started making sense. Very focused on France, it was always in a context of conflict. The avant-garde artists were fighting the galleries. They were fighting the formal artists. There was a sense of rebellion in modern art, which appealed to the rebel in me. I was ready for rebellion.

In my second year at university my mother told me that Uys Krige would give a lecture and that maybe I would be interested in attending. He spoke about Federico Garcia Lorca, the Spanish poet, being executed by firing squad at 5 p.m. Then he read the Pablo Neruda poem ���At Five in the Afternoon,��� and he walked up and down the stage reciting at five in the afternoon. He spoke for about two hours non-stop. The poem reached right into me. It did something very important. It connected the dreaminess, the longing, the soulfulness with public events, with action, with the world. The interior and exterior, the drama and emotion, of internal dreams and imagination, and the passions of struggles and fights for freedom got connected through that lecture. A few weeks later I was volunteering for the 1952 Defiance of Unjust Laws Campaign.

Albie at the Congress of the People, Kliptown, as police enter the gathering ��� June 1955. Photo: Eli Weinberg Collection, Robben Island Museum Archives. Riason Naidoo

Albie at the Congress of the People, Kliptown, as police enter the gathering ��� June 1955. Photo: Eli Weinberg Collection, Robben Island Museum Archives. Riason Naidoo You write in The Jail Diary of Albie Sachs (1966) that while in solitary confinement in 1963 you whistled many pieces of music and resistance songs���Beethoven���s Fifth Symphony, ���La Marseillaise,��� ���We Will Follow Luthuli,��� ���The Red Flag,��� ���Let���s Twist Again,��� ���Goin��� Home��� from Anton��n Dvo����k���s New World Symphony, Miriam Makeba songs, Ella Fitzgerald and Louis Armstrong tunes, ���Goodnight, Irene������to pass the time and keep you sane. Could you reflect on how the memories of songs impacted on you in those times?

Albie SachsPrison is filled with sound, ugly sound. Doors slamming, commands being issued, drunks screaming and banging. A kind of a tattoo that would go on. I���m singing these songs to myself. I���m working my way through the alphabet. This I remember. [Albie sings.]

Always���I���ll be loving you, always.

I���ll be living here always,

Year after year always,

In this little cell that I know well,

I���ll be living swell always, always.

I���m amused that Irving Berlin���s love song to his wife is keeping the heart of a would-be revolutionary in a Cape Town prison alive. [He continues.]

I���ll be staying in always,

Keeping up my chin always,

Not for but an hour,

Not for but a week,

Not for 90 days, but always.

I sing that song quite often when I���m touring, especially if there are judges in the audience. I don���t think they���ve ever heard a judge make a presentation singing. The whistling was fantastic because suddenly there was somebody whistling back. The person didn���t recognize the ANC songs. The person didn���t recognize ���The Red Flag.��� The first melody that we had in common was the ���Goin��� Home��� theme. After being released some months later, I met Dorothy Adams, and she belonged to another political group led by Neville Alexander. So there we were. Different political cultures, both involved in anti-apartheid resistance, both detained without trial, both having the hardest experience of our lives. My whistling of the ���Goin��� Home��� theme has come back into my life. It now appears on the landing page of a website on my life and work being developed by George Clooney and his wife Amal Clooney (n��e Alamuddin), with Clooney���s drawing of an award figure���which he and Amal call The Albie given to persons who fight against the odds for justice���animated on the opening page.

Albie hugs Dorothy Adams at a benefit performance of ���The Jail Diary of Albie Sachs��� at the Young Vic in London ��� late 1988. Photographer unknown. Riason Naidoo

Albie hugs Dorothy Adams at a benefit performance of ���The Jail Diary of Albie Sachs��� at the Young Vic in London ��� late 1988. Photographer unknown. Riason Naidoo While incarcerated you were later given access to literature. You write, ���There is no doubt about what kind of books I want. I want to read novels, books alive with people, people who talk, mingle with each other and undergo all the normal emotions of life. I want to escape, but escape into the world of reality.��� What is the power of fiction for you, and what does it tell us about life in general? Is there a connection?

Albie SachsI���ve always loved reading since I was very young. There were some memorable books by a left-wing writer called Geoffrey Trease: one called Bows Against the Barons; another, Call to Arms, was set in Latin America���of revolutionaries fighting against a despotic government. These were books geared to the imagination of someone living in an atypical home in South Africa. Some of my mother���s close friends were Cissie Gool and Pauline Podbury. Gool was a fiery speaker and city councilor, daughter of the famous Abdullah Abdurahman political family. Podbury was married to H. A. Naidoo from Durban, and they were both in the trade-union movement. My mother had many strong women friends. I didn���t have a chance. I became a feminist, if not from birth, from early childhood. That was my milieu.

I discovered French literature, Balzac, Guy de Maupassant. My imagination was stirred by French and then Russian literature, especially Tolstoy and Dostoevsky. Tolstoy���s War and Peace was an obligatory read during a gap year in London when I was 20. At a later stage, Italian literature. German writer Thomas Mann���s The Magic Mountain was influential too. I read three or four novels by the Spanish writer P��rez Gald��s.

I enjoyed Vanity Fair by William Thackeray. It had something extra. I liked reading about the world in a town called X, Russian names, French names. It was part and parcel of transporting me to another world. The idea of reading South African fiction did not appeal to me. A big transition moment for me was reading The Lying Days by Nadine Gordimer. It had that quality of transporting me into another universe. I have to thank Nadine for opening me up to South African imagination and literature.

Another big breakthrough was Ng��g�� wa Thiong���o. I read most of his novels. I met Micere Mugo in Nairobi, and later when she was in exile, who was a professor of English literature and part of that generation of rebels. Alex La Guma was a huge hero for me as a writer. We worked in the resistance in Cape Town together. The book of his I like the most is The Stone Country, about the Roeland Street Prison, where he was locked up, and I where was locked up too.

A big cultural influence in my early years was film. I belonged to the film society in Cape Town. I saw lots of Eisenstein, Pudovkin, and Italian post-WWII Neo Realism and Surrealist works.

Riason NaidooSome of the authors you refer to in your jail diary are Durrell, Henry James, Proust, George Eliot, Racine, Melville, Moss Hart, Mary Renault, Jan Rabie, Venter, C. P. Snow and Lampedusa. Who are some of your current favorite authors?

Albie SachsDuring my time in jail the court ordered that I have books. Later on that was rescinded again by the top court in the country banning literature for prisoners. After my release I was so worried about being caught without reading matter that when I traveled I would take a whole lot of books with me. I thought I must not be caught without a book again. The books I read now are thrillers. I judge my holidays by the number of thrillers I read by the likes of Jo Nesbo, et al., and especially those set in Nordic countries, France, Italy or Japan.

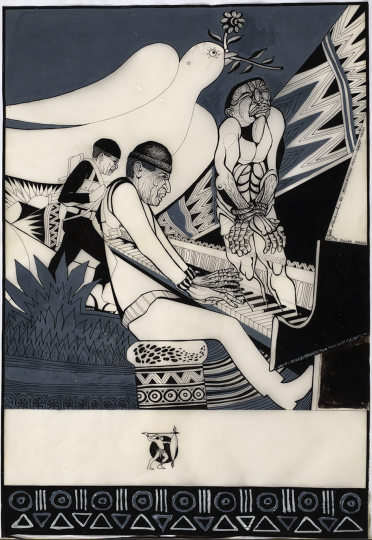

Riason NaidooYou made a book, Images of a Revolution (1983), of mural art in Mozambique (and a documentary too). What did you appreciate about that project?