Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 10

June 9, 2025

The end of AGOA

Photo by Rosie Kerr on Unsplash

Photo by Rosie Kerr on Unsplash On Wednesday, April 2, 2025, when President Donald Trump issued an executive order introducing reciprocal tariffs to all countries, my article analyzing the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) and the possibility for its renewal before its expiry on September 30, 2025, was nearly complete. However, within a day, the terms of trade with the United States had changed so radically that even the concept of AGOA reauthorization is far out of reach. The new tariffs override AGOA, so countries exporting to the US will no longer enjoy duty-free market access and will instead have to pay reciprocal duties.

Yet I still believe that it is important to have a knowledge exchange on AGOA, and to analyze the Janus-faced relationship that is US trade relations with Africa. Without a doubt, it is important to situate these new tariffs against the existing precarity of the US-Africa trade relationship, so as to remind us all that though it feels like we are living in unprecedented times���with regard to the overt mercantilism of US trade and foreign policy (USAID shutdown, Trump tariffs, etc.)���the reality is that the trade relationship between the US and Africa has always been precarious, and the power balance has always skewed towards the US. To me, AGOA is still worth discussing because it may help us understand and predict US trade policy going forward, and perhaps prompt us to find ways to interrupt the current hierarchical structures of trade between African countries and ���developed��� country trading partners.

What is AGOA?AGOA is a preferential trade arrangement unilaterally granted by the US to eligible countries in what we have come to know as Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Enacted in 2000, AGOA allows beneficiary countries to access the US market on a duty-free basis and covers over 6,000 products. The US developed AGOA as an instrument for facilitating an economic relationship with Africa, and to date, it is the only trade arrangement that the US has with any country in SSA. Currently, there are 32 countries eligible for AGOA, and we will return to the matter of eligibility in a moment. First, I want to take a step back and situate AGOA within the larger multilateral trading system���the World Trade Organization (WTO).

A central principle of the WTO is the principle of most-favored-nation treatment. This means that countries agree to levy the same duty to all member countries of the WTO ensuring transparent and predictable trade. However, the agreement has several provisions (special and differential treatment provisions) that grant ���developing��� countries special rights. One of these provisions is the Enabling Clause, which provides them with a legal basis to provide nonreciprocal preferential treatment (including zero duty or lower tariffs on imports) to ���developed��� countries. This provision is the basis for the Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) and other nonreciprocal preferential trade arrangements including AGOA. In 1975, the US GSP, a broad-spectrum provision that offered benefits to over 100 countries across the world, came into force. This GSP offered duty-free treatment for over 3,600 products and offered additional duty-free treatment for 1,500 products from what are known as least-developed beneficiary countries (LDBCs).

Twenty-five years later, AGOA was birthed. And despite the fact that many SSA countries were eligible under the GSP, the US envisioned a new arrangement designed to foster a ���more meaningful��� partnership with Africa. AGOA beneficiary countries could now enjoy additional benefits over and above the US GSP, including wider product coverage for duty-free treatment and trade-related support from the US to ���capacity build��� countries to take advantage of AGOA. However, to benefit from this new lucrative market opportunity, SSA countries must meet the eligibility requirements. The United States Trade Representative (USTR) provides that for countries to be deemed eligible under AGOA, they ���must establish or make continual progress toward establishing a market-based economy, the rule of law, political pluralism, and the right to due process. Additionally, countries must eliminate barriers to U.S. trade and investment, enact policies to reduce poverty, combat corruption, and protect human rights.���

Now we return to the matter of eligibility. Of 49 countries in SSA, only 32 countries are AGOA-eligible. While Equatorial Guinea and Seychelles are ineligible because they have developed beyond the income threshold for AGOA, other countries such as Burkina Faso, Gabon, Guinea, and Niger are ineligible because the US does not approve of their ���rule of law��� or political environment and leaders, so to speak. The ineligibility mechanism of AGOA draws our attention back to the precarity of the agreement. Put simply, eligibility is dependent on implementing the US���s prescribed political and economic policies. From a political economy perspective, AGOA appears to be structural adjustment programs (SAPs) rebranded and re-deployed to a new sphere���international trade. Conditionality was an integral component of the 1980s International Monetary Fund (IMF) lending program to so-called developing countries. This framework has been heavily criticized, with many studies showing the destructive impact of the SAPs. Yet, and perhaps regardless of these studies, unilateral and nonreciprocal preferential trade arrangements like AGOA continue to include conditions. Unlike trade agreements with two or more countries negotiating the terms of access into each other���s markets, unilateral trade arrangements are designed by the granting country. This means beneficiary countries rely on the good will of the granting countries successive administrations to continue accessing these markets duty free. This brings us rather neatly on to the matter of AGOA today.

AGOA todayAGOA has been renewed several times since its inception, with the last renewal occurring in 2015. It is set to expire again on September 30, 2025. In anticipation of the expiry of the act, on April 11, 2024, US Senators Chris Coons and James Risch introduced the AGOA Renewal and Improvement Act 2024. The new act proposed an extension of AGOA by another 16 years, until 2041. Interestingly, the Biden administration (which contrary to expectations, did not reverse any of the first Trump administration���s trade policies and, in some cases, doubled down on them) did not pass the bill and instead left it as a pending matter to be dealt with by the incoming administration.

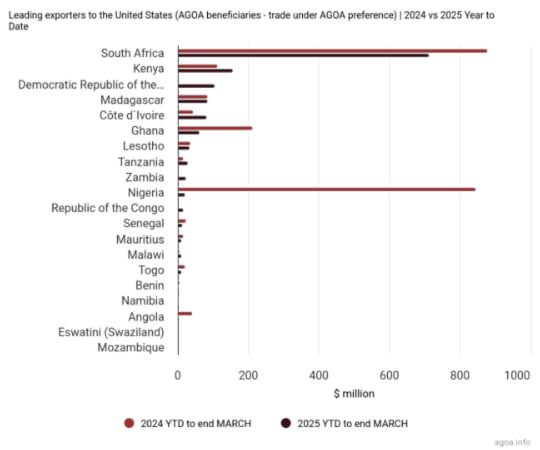

Here we begin to see the effect of the huge power imbalance between this US-Africa partnership. For the US, imports from Africa account for a measly 2 percent of all imports. For the 32 SSA countries that are still eligible for AGOA, the agreement represents millions of dollars in revenue and hundreds of thousands of jobs. The chart below illustrates the economic significance of AGOA to beneficiary countries.

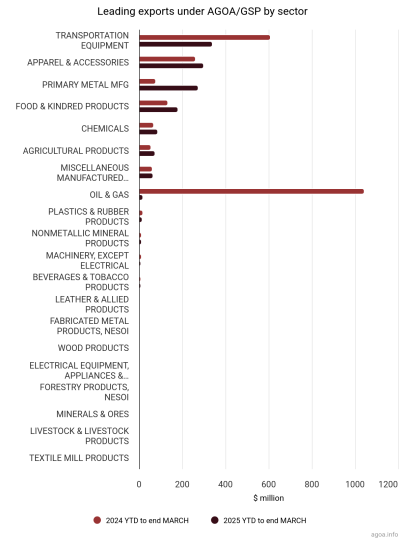

While a macroeconomic analysis of AGOA would show that very few African countries actually export under AGOA (chart 1), I think macroeconomics has a way of creating abstract paintings out of people���s very real experiences. AGOA utilization is low, yes, and for many reasons that are beyond the scope of this article. However, for the countries and sectors that utilize AGOA (chart 2), the export opportunity created by the duty-free access to the US market represents people���s livelihoods, businesses, education, health care, and so much more.

Chart 1 via AGOA.info

Chart 1 via AGOA.info Chart 2 via AGOA.info

Chart 2 via AGOA.infoAGOA reauthorization has been on the agenda for African countries. However, even before Trump���s ���Liberation Day��� tariffs, the prospect of AGOA renewal was dim. In March, former US Ambassador to Kenya Kyle McCarter cast further doubts about the extension of AGOA stating that AGOA was not part of the administration���s agenda. He added: ���AGOA is a one-sided agreement and is set to the benefit of Kenya and not the US. You can���t classify AGOA as a reciprocal trade [arrangement] and it���s been very clear from President Trump that every arrangement is going to be win-win.���

The current administration���s push for reciprocity (as defined exclusively by them) and complaints about the US not benefiting from existing trade agreements or arrangements aren���t new phenomena in US trade policy. We need to interrupt and question the narrative that these are solely Trump administration policies.

As I mentioned earlier, the Biden administration did not reverse most of Trump���s tariffs, adopting Trump���s arguments that unequal trade was in a large part to blame for the shrinking middle class and industrial base. However, since 2001, when China joined the WTO, the US policy makers have continually blamed the multilateral trading system for the decline of US economic power. While the WTO has received very valid criticism on how the design of the agreement has produced and grandfathered unequal trade relationships between the ���developed��� and ���developing��� world, this is sadly beyond the scope of this article. Instead, I want to bring to light that China���s joining the WTO is directly correlated with the US weaponization of trade.

Let me set the stage briefly: It���s the year 2000, and China is on a campaign to join the WTO. The Clinton administration, seeing an opportunity to bring China to the liberal market economy, actively supports, nay, champions China���s accession. China joins the WTO in 2001, and trade between China and the US skyrockets due to lower duties and other market-access benefits, increasing from less than $100 billion in 1999 to $558 billion in 2019. As trade between the countries increases and the Chinese economy expands at an astronomic rate, China���s trade practices start to be questioned, with many countries arguing that China is not playing by the WTO rules. The long and short of it is that the US felt that the WTO was not doing a particularly good job at reining in China, and as such, the organization���s relevance in international trade was no longer valid.

Contrary to popular media���s current narrative, the weaponization of trade did not start during Trump���s first administration; instead, we can trace its foundations back to the Bush administration and the beginning of the US-China Trade War. This trade war has come to redefine the US���s attitude to multilateralism, a concept that the nation championed in the 1940s during the establishment of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT)���the predecessor of the WTO. My central argument here is that the US has been on a long road to rescinding AGOA and weaponizing trade policies as an instrument to gain and maintain their economic and political power vis-��-vis China.

Sure, Trump���s ���America First��� protectionist and mercantilist policies may have accelerated things, but arguably, it was only going to be a matter of time before the US turned its trade-as-war policy to fashion a more ideal (for the US) relationship with Africa, where the US has substantial ���national security��� interests.

June 6, 2025

Go��ta, gift to the insurgents

Malian Army soldiers in Bamako, 2024. Image �� ChiccoDodiFC via Shutterstock.

Malian Army soldiers in Bamako, 2024. Image �� ChiccoDodiFC via Shutterstock. On May 13, 2025, the government of Mali, citing ���public order,��� outlawed and dissolved all political parties. Since taking power, following two army coups in 2020 and 2021, interim President Assimi Go��ta���s politics have been marked by strong nationalist rhetoric. Go��ta has positioned himself as a defender of Mali���s sovereignty, pushing back against foreign influence and redirecting Mali���s foreign policy away from traditional allies. Significantly, France was obliged to withdraw its Barkhane army forces from Mali in February 2022. But the Malian ruling military junta went even further when it pushed out the UN���s Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) and put an end to the 2015 Algiers Accord.

In place of these alliances, security assistance has increasingly been provided by Russia���s paramilitary Africa Corps, formerly known as the Wagner Group, as well as by Morocco. The latter is aggressively more present in the Sahel region, offering closer partnerships and economic cooperation with Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso, the three countries of the Alliance of Sahel States. Rabat is luring these landlocked states into a project that promises to provide access to the Atlantic Ocean through the occupied territory of Western Sahara.

In addition to these new alliances, Go��ta has also claimed to tackle corruption and restructure Mali���s institutions to rally support from the Malian population. Such populist discourses and maneuvers appeal to numerous Malians who are tired of elite impunity and government inefficiency. Indeed Go��ta���s promises resonated with many Malians frustrated by years of foreign military presence, poor security and economic conditions. Yet, there have been no significant improvements to any of the above since Goita took power four years ago. Since February 2022, the transitional government has repeatedly delayed elections, citing ���technical reasons��� and eventually proposed a presidential term extension until 2030. There are rising concerns about Goita���s authoritarian style, particularly after he promoted himself to the rank of general in 2024.

The postponement of elections was the immediate trigger that sparked demonstrations by opposition political parties in early May. Rather than acknowledging demands for a return to constitutional order by December 2025, the government quickly issued a ban on all political parties.

The political crisis has economic roots. Despite numerous promises from Go��ta���s government, living conditions for most Malians remain dire, with the economic growth being largely concentrated in urban areas and major cities, and rural areas remaining neglected. For example, the ratio of GNP between urban and rural areas is 5.5% in Mali and sub-Saharan Africa globally, compared to only 2.7% in India. Meanwhile, corruption in Mali is rampant. After taking power, the junta was quick to point out the deep corruption present in the different governing circles, promising to rapidly tackle the problem. However, to date, poverty has increased, and Malians are struggling to survive.�� A nouveau riche is emerging, as new houses for the colonels have recently ���sprung up like mushrooms.��� One member of the junta, Colonel Sadio Camara, allegedly feeds several horses in his yard where there are two stables.

The latest events in Mali are likely to bring not only further political instability but also provide impetus to armed and militant jihadist groups active across the country. Indeed, this latest step from the military authorities in Bamako is likely to spark deep discontent among the population, and will undoubtedly encourage more youth to join militant groups present in Mali and in the Sahel region, as well as further southwest on the continent. Such groups are already on the attack; one such attack, in April in Benin, saw the�� Jama���at Nusrat al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM) kill at least 54 soldiers in the north of the country. Although militant groups point out the economic failure and political shortcomings of the Sahelian states, the presence of foreign powers in the Sahel region has made things worse. European states such as France and Germany have on different occasions paid ransoms to liberate their citizens kidnapped in the region, yet they have contributed to financing militant groups in the Sahel. The presence of France���s military forces from 2013 provided fertile ground for both extremist groups and a large fringe of the Malian population, which the Malian military junta exploited in their quest for legitimacy following their 2020 coup.

Jihadist groups such as JNIM and ISIS-Sahel will have no difficulty in further pointing out the failure of Go��ta, convincing more Malians to join their ranks. These groups largely capitalize on socioeconomic grievances to recruit members and legitimize their control of villages and regions that the central authorities of Bamako have been unable to govern for years.

Meanwhile, the increasing use of the internet provider Starlink will facilitate further recruitment, with technology reaching people living in remote places. It is publicly known that militant groups in Mali and in the Sahel in general, are already exploiting Starlink to enhance their operational capabilities. Starlink will also perpetuate organized crime, which is already well-rooted in the Sahel. The black market in Mali and the Sahel in general facilitates an illicit supply chain through which devices such as Starlink can be obtained.

In providing a mobile and easy-to-use communication tool, militant groups will have little difficulty recruiting many Malians who live in isolated rural regions. These populations will increasingly fall prey to extremist discourses that also point out the failures of the state.

After forcing Barkhane and MINUSMA to leave Mali, divorcing ECOWAS and declaring the Algiers Accord dead, Bamako has turned to new friends and allies such as Africa Corps, the United Arab Emirates, and Morocco. However, and as the former US national security adviser, John Bolton, noted, Morocco���s [regional] territorial aspirations do not include only Western Sahara but also large portions of northern Mauritania and western Algeria. Undoubtedly, Morocco���s territorial aspirations should be a warning to Bamako.

Meanwhile, acute economic development, insecurity linked to terrorism and organized crime remain entrenched in the Malian socio-political and economic landscape. And neither the Malian army nor Go��ta���s new allies have so far been able to address these issues. There is no doubt that the latest move from Go��ta will only fuel this insecurity, putting the entire Sahel-Maghreb region at a higher risk of instability.

June 5, 2025

Hollywood gloss and cinematic Afropology

Still from No Chains, No Masters �� 2024.

Still from No Chains, No Masters �� 2024. The sound of rustling leaves is swallowed by the heavy breathing of those who run. The land is dense, but there is no stopping now. There is a place beyond the trees, a place where the enslaved live free. The girl and her father have heard stories: Some say they are nothing more than myths, whispers passed down from those who dream of freedom. But the ones who believe know the name. Mame Ngessou: a spirit who watches, one who lives in the water and hears the call of the stolen.

In Simon Mouta��rou���s Ni cha��nes ni ma��tres (No Chains No Masters), history and myth are inseparable. The film follows Mati and Massamba, a father and daughter enslaved on a French plantation in 1759, who flee a world where survival means submission. Beyond the plantation, the maroons���Wolof, Ashanti, others whose names have been lost to colonial records but who have made new names for themselves in the shadows���await the duo. Like Mati and Massamba, they are bound by nothing but the refusal to be owned.

This is no heroic escape, no triumphant arrival. Freedom is fragile, always one step ahead but never fully within reach. The French slave captors find them. The chase ends at the edge of a cliff. Below, the ocean stretches wide, infinite. To jump is to choose death. To surrender is to return to the chains.

The maroons make their decision. They hold hands, one by one, singing as they step forward. A woman with a child in her arms. A man who closes his eyes and steps into the abyss. The slave hunters stand frozen before an act they cannot control. Last are Mati and Massamba. They do not weep. They look at one another and step forward, hands clasped, bodies suspended for a fleeting second before finally meeting the sea.

Western narratives about slavery often follow a linear progression: suffering, endurance, and eventual liberation���either through escape, revenge, or legal justice. In 12 Years a Slave, Solomon Northup endures, survives, and is eventually freed. In Django Unchained, revenge is the currency of liberation. In Amistad, justice comes through legal arguments in a white courtroom. These films frame time as something that moves forward toward resolution; Ni cha��nes ni ma��tres offers no such resolution. This is not a film about endurance or individual redemption. It is about collective refusal.

Ni cha��nes ni ma��tres refuses the spatial and temporal structures imposed by Western storytelling. Mouta��rou���s film rejects the notion of a promised land entirely. Unlike Western narratives that position escape as an endpoint, Ni cha��nes ni ma��tres presents flight as something cyclical, unstable, and impermanent. Mati and Massamba reach the maroon community, the promised land whispered about in hushed voices. For a brief moment, it appears as though their journey has ended and freedom has been secured, but this promise is fleeting. Because their newfound refuge does not exist outside the colonial system, it is only a temporary shelter, always at risk of being found and destroyed. The illusion of stability shatters when the cycle begins again: The French captors descend, forcing them back into flight.

Mouta��rou���s film disrupts the Western cinematic expectation that escape leads to resolution; instead, freedom remains provisional, constantly deferred, never fully realized. Mati and Massamba���s leap into the ocean does not mark the end of their struggle but the final rupture of colonial time itself. This rejection of colonial time aligns with real histories: In the many maroon communities of Haiti, Brazil, and the Caribbean, enslaved people did not wait for freedom to be granted; instead, they chose to live outside the colonial state and form societies that rejected its legitimacy. It harkens back to the famed Igbo Landing (1803), where captured Igbo people walked into the sea rather than be enslaved.

Western cinema struggles with narratives that defy resolution. It demands catharsis, a singular hero, and a system to overcome, producing a binary imagination where Africa is either a spectacle of suffering or a utopian fantasy. This is the Africa of Black Panther, The Woman King, and other films that erase or distort history for entertainment. While Black Panther was widely celebrated, its Afrofuturist vision of Wakanda imagines an Africa severed from colonial histories. It is a speculative utopia���visually stunning, but removed from material realities.

When Hollywood does engage with history, it often reduces it to spectacle. Slavery narratives linger on lashings, bloodied backs, and prolonged suffering, translating Black pain into a cinematic aesthetic of endurance. The violence is stylized, eliciting emotion rather than interrogation. Whether through fantasy or suffering, Africa is stripped of its contradictions, struggles, and lived realities in favor of a clean, digestible narrative of brutality. This aestheticized suffering���a careful balancing of emotion and detachment���is what gives Hollywood���s portrayal of history its distinct sheen, one that feels immersive but never fully disruptive. The slow-motion anguish, the swelling orchestral scores, the carefully composed shots of despair move audiences, particularly non-Black viewers, without forcing them to reckon with the structures that produced such suffering. For Black audiences, these depictions can retraumatize, offering little in the way of critical confrontation. Hollywood glosses over history to contain discomfort and render brutality as sublime.

Mouta��rou���s cinematic narrative is in line with other filmmakers like Mati Diop and Alice Diop, both of whom continue to challenge the flattening of African history in film. Their movies engage in a cinematic afropology that rejects Western demands for resolution and containment. Films like Ni cha��nes ni ma��tres, Dahomey, and Saint Omer refuse triumphant endings, singular heroes, or clear moral takeaways. Instead, they confront history on its own terms, embracing its gaps, contradictions, and unresolved tensions. They experiment with narrative ambiguity, temporal rupture, and compositional silence as tools for historical reckoning.

Mati Diop���s Dahomey materializes these contradictions through form and dialogue. The latter half of the film shifts into a chorus of young Beninese students debating the meaning and limitations of repatriation. Their voices clash: Some emphasize the importance of reclaiming what was stolen, while others question the motivations behind the return of 26 out of the estimated 7,000 looted artifacts. The conversation touches on a loss of language and culture, the role of political leaders and whether these symbolic acts do anything to address their present-day conditions. Diop captures this dissonance without editorializing, allowing the students��� perspectives to collide, overlap, and contradict one another. Rather than offering closure, Dahomey becomes a space where postcolonial realities are laid bare���messy, unresolved, and impossible to reduce to a single meaning.

Alice Diop���s Saint Omer likewise rejects a framework of moral closure. Where Hollywood might have turned the real-life case of Fabienne Kabou into a sensationalized courtroom drama, Alice Diop offers a restrained, introspective film that interrogates race, migration and the unseen violence of otherness in contemporary France. Its protagonist, Laurence Coly, a Senegalese woman accused of infanticide in France, is rendered neither victim nor villain. The film does not offer her redemption or allow easy condemnation, forcing the viewer to sit in the discomfort of the unresolved space of her existence. Like Ni cha��nes ni ma��tres and Dahomey, Saint Omer insists that the traumas of slavery, migration, and alienation are unresolved wounds.

At its root, Saint Omer is a film about displacement���both physical and psychological. Laurence left one world behind but has not been fully accepted into another. She is alienated by both Senegalese and French spaces. Alice Diop criticizes expectations that postcolonial subjects who immigrate should be grateful, should assimilate without friction and should leave behind the ghosts of their past. Laurence���s story exposes how assimilation is a demand���not an invitation���that requires an impossible and violent severance. Diop frames the character���s crime���drowning her own daughter���as not just an individual act of desperation but a symptom of something larger. Was it an act of mental collapse? A response to the suffocating pressure of being a Black woman in France? A rejection of the burden of representation placed on migrant mothers? Diop offers us no answers, leaving us to wonder whether it is all of these elements, or perhaps none of them at all. Her camera lingers, holding the audience in prolonged quiet moments that withhold closure, forcing us to confront ambiguity rather than escape it.

The refusal to conform to Western storytelling conventions is a political one. Ni cha��nes ni ma��tres, Dahomey, and Saint Omer reject the idea that history must be neatly contained, that survival equates to freedom, or that suffering must be spectacularized to be understood. By breaking away from the imposed linearity of mainstream cinema, these films open space for new ways of seeing, remembering, and resisting. They remind us that history is not a closed book, nor is it something to be repackaged for easy consumption. It lingers, unresolved, pressing against the present. Perhaps this is the greatest act of defiance���refusing to give history a conclusion.

June 4, 2025

Between Washington and Beijing

Port of Lagos, Nigeria. Image �� Oussama Obeid via Shutterstock.

Port of Lagos, Nigeria. Image �� Oussama Obeid via Shutterstock. The global economic balance of power is shifting, and Africa finds itself at a crossroads. The traditional dominance of the US in shaping trade and aid policies is receding, creating both peril and possibility for African nations. Recent disruptions���from protectionist tariffs launched in Washington to the outsized influence of tech billionaires���have exposed how vulnerable Africa���s economies remain to external decisions. The once-stable antagonistic cooperation between Washington and Beijing, which long shaped the contours of the global order, now appears to be waning. Yet these shocks are also spurring a long-overdue conversation about self-reliance and sovereignty. Can Africa turn a decline in US influence into an opportunity to chart its own course, or will new dependencies simply replace the old ones?

US President Donald Trump���s trade wars epitomize the jolts to the system. His administration���s sweeping tariffs did not stop at China���they struck African countries as well, abruptly undercutting the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), which for two decades had given African exporters preferential access to US markets. The effects were immediate and painful. In Lesotho, for instance, a flourishing garment industry that depended on tariff-free exports to American retailers suddenly faced levies of up to 50% on its goods. Thousands of factory workers���mostly women���saw their jobs put at risk overnight as orders evaporated and profit margins vanished. In Kenya, flower farmers braced for a 10% tariff hike on horticultural exports, threatening to price them out of the market. These were not mere economic policy shifts���they struck at the livelihoods of households and communities that had pinned their hopes on global trade.

Trump���s tariffs on African countries reached as high as 50% on goods from Lesotho, with steep duties also hitting Madagascar, Mauritius, and others. Industries painstakingly built under AGOA���s duty-free framework were thrown into crisis.

For African policymakers, the tariff shock was a rude awakening. It exposed how fragile the continent���s place in global trade truly is when a single policy reversal in Washington can upend entire sectors. ���Can we continue to rely on the US, or is it time to find a path of our own?��� became the question animating high-level discussions across the continent. The call for diversification grew louder. For decades, Africa���s development strategy had been anchored to ties with the US and Europe���ties that now revealed themselves to be tenuous, even illusory. Trump���s protectionism, though damaging in the immediate term, has forced a reckoning: Africa must reduce its overreliance on any single foreign market. If the status quo can no longer be taken for granted, then perhaps this moment of crisis might also serve as a catalyst to imagine a more independent economic future.

When billionaires shape foreign policyTrade is only one side of the coin. Even as African nations grappled with tariff whiplash, a new challenge to their sovereignty has emerged���driven by powerful private actors like Elon Musk, the tech magnate-turned-policymaker. Under the auspices of a Trump-era initiative tellingly dubbed the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), Musk spearheaded an aggressive campaign to slash what he considered ���wasteful��� federal spending, including US foreign aid. In an unprecedented arrangement, the billionaire was effectively handed the reins to remold parts of the US government���s role abroad. One of Musk���s prime targets, the US Agency for International Development (USAID), has long provided development assistance to African countries.

Musk���s cost-cutting crusade quickly translated into severe aid reductions. Programs that had been funding health clinics, schools, and infrastructure across Africa were abruptly scaled back or terminated. The consequences have been dire. In March, the World Health Organization warned that the US decision to ���pause��� foreign aid deliveries had ���substantially disrupted��� the supply of HIV/AIDS medications in at least eight countries, including Kenya, Lesotho, and South Sudan���nations that could run out of life-saving treatments within months. Decades of progress against the HIV epidemic now risk unraveling, with officials fearing as many as 10 million additional infections and three million deaths if these disruptions continue. In Uganda, which relies heavily on US-funded HIV programs, clinics have already begun rationing antiretroviral drugs���a grim step backward into crisis. These cuts are more than just numbers on a budget sheet; they are measured in human lives, as the US retreat from foreign aid, led by Trump and Musk, has gutted support for some of the most vulnerable populations.

What makes this scenario especially unsettling for Africa is the erosion of accountability that comes with private influence over public policy. Musk is an unelected actor wielding outsized power: decisions made in a Silicon Valley boardroom���or an Oval Office backchannel���can determine whether a village clinic in Mali stays open, a clean water project in Kenya dries up, or maternal health programs in Ethiopia are shuttered. This trend, in which billionaire ���diplomats��� shape the destinies of nations, raises urgent questions about democratic oversight and sovereignty. Who ultimately holds the reins when development priorities can be reset on a whim by corporate titans? For African states used to negotiating with official departments and diplomats, the new paradigm is disorienting. It���s no longer just Washington���s whims they must navigate, but those of individuals operating far outside any diplomatic framework. Musk���s influence is a harbinger of a world where private wealth dictates the terms of global governance���often sidelining the governments of the very countries most affected.

The convergence of Trump���s tariff nationalism and Musk���s corporate-driven agenda lays bare a hard truth: Africa���s economic fortunes are still far too subject to decisions made elsewhere, for interests other than Africa���s own. Whether it���s a US president pursuing an ���America First��� trade policy or a tech CEO advancing a technocratic vision of efficiency, the result for Africa is the same: loss of agency. Each has challenged African leaders to ask: Are we masters of our own fate, or merely pawns in someone else���s game?

Yet amid these challenges, a cautious sense of empowerment is emerging. By exposing the pitfalls of dependence, Trump and Musk may have inadvertently done Africa a favor. They have made it impossible to ignore the structural vulnerabilities that have long been apparent. As one pillar of external support after another collapses, African nations are being forced to accelerate conversations about self-sufficiency and regional integration that have simmered for years.

New partners, old risksIf the US is stepping back���or pushing Africa away���who will fill the void? One obvious answer is China. In the past two decades, China���s presence in Africa has grown from a curiosity to a cornerstone of the continent���s external relations. Through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), Beijing has poured money into highways in Kenya, railways in Ethiopia, ports in Tanzania, and beyond. For many African governments, China���s willingness to finance big-ticket infrastructure has been a godsend, especially as Western aid and investment waver. In the wake of Trump���s tariff shock, analysts predicted that Beijing would waste no time presenting itself as a more stable, ���rules-based��� partner���one that wouldn���t yank away market access on short notice. China has long emphasized its commitment to consistent engagement, a message likely to push countries even closer to its orbit.

But if US influence came with strings, so too does China���s. Critics warn that BRI projects can devolve into ���debt-trap diplomacy,��� a new form of economic subjugation by another name. The formula is familiar: Chinese state banks offer huge loans for infrastructure, African states eagerly accept, and when repayment becomes impossible, Beijing gains leverage���whether in the form of control over strategic assets or greater influence over domestic policymaking. Already, countries like Zambia and Sri Lanka���a cautionary tale outside Africa���have struggled with unsustainable debt linked to Chinese funding. Critics argue the BRI functions as a development scheme that saddles countries with unaffordable loans, leaving them vulnerable to coercion and weakening their sovereignty.

From an African perspective, the picture is more nuanced. Leaders like South African President Cyril Ramaphosa have pushed back on the ���debt trap��� narrative, arguing that Chinese investment, if managed prudently, fills crucial development gaps and that African states are not passive victims. Chinese capital has indeed built roads, power grids, and other infrastructure where it was desperately needed. And unlike Western aid, it often comes with fewer lectures on governance or human rights. Still, the long-term implications must be weighed. Who owns the mines and minerals after the deals are signed? Are local workers and businesses benefiting, or just foreign contractors? If a railway is built with Chinese loans and operated by a Chinese firm, how much of the profit stays in Africa? These questions strike at the heart of sovereignty: can Africa truly be sovereign if its most critical assets are externally controlled, whether by Washington or Beijing?

The same caution applies to other emerging partners. For example, India, Turkey, and the Gulf states have also increased trade and investment across Africa in recent years. They offer African governments more diplomatic options and the promise of diversified economic ties. In theory, this competition for African markets could increase African leverage���a chance to play suitors off one another for better terms. But in practice, it could also become a race to the bottom. Without clear-eyed strategies and strong negotiating positions, African nations risk simply replacing one set of extractive arrangements with another.

Ultimately, diversifying external relationships���whether through trade deals with Asia or South-South cooperation���is a necessary strategy, but not a sufficient one. True autonomy won���t come from swapping patrons. It will come from reducing the need for patrons altogether.

The promise of AfCFTA and regional integrationOne bright avenue for reducing external dependence is strengthening ties within Africa itself. The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), operational since 2021, is an ambitious project aiming to knit together 54 African countries into a single market of 1.4 billion people with a combined GDP of $3.4 trillion. It represents Africa���s boldest effort yet to boost intra-continental commerce, which currently makes up only about 15% of Africa���s trade, compared to over 60% in Asia and 70% in Europe. The logic is straightforward: if African countries trade more with each other, they will be less beholden to external markets. A more self-contained African economy could better withstand global shocks���whether financial crises, pandemics, or the whims of foreign leaders���because it would spread risk across a broader internal base.

Early analyses of AfCFTA���s potential are encouraging. The World Bank estimates that by 2035, full implementation of AfCFTA could raise Africa���s exports by 32% and lift tens of millions of people out of poverty. It could also make the continent far more attractive to investment in manufacturing and services, as companies tap into economies of scale beyond their home country. In short, AfCFTA aspires to do nothing less than reconfigure the African economy���shifting it from an exporter of raw commodities into a diversified production base serving African consumers. Over time, this could help break the historic pattern where Africa sends out unprocessed minerals and crops and buys back finished goods at a premium, a cycle that has perpetuated underdevelopment since colonial times.

However, turning the paper agreements of AfCFTA into real commerce on the ground is a formidable challenge. Infrastructure gaps are a major bottleneck���you can���t trade if you can���t transport goods efficiently from an inland factory to a port or land border. Many African countries still lack reliable roads, railways, and electricity to support industrial growth. Customs procedures and regulatory standards need harmonization to ease the passage of goods. And some countries remain wary that opening up their markets might undercut local industries in the short term.

Implementing AfCFTA will require not just political will but also significant investment in connectivity and competitiveness. It is encouraging that even amidst these concerns, regional blocs and governments are actively working on these issues���from new cross-border highway projects to unified customs protocols. The direction is clear: Africa sees regional integration as key to its economic future, even if the journey will be long.

Beyond dependencyWhether dealing with Washington, Beijing, or any other capital, one theme becomes apparent: Africa���s leverage will ultimately depend on its internal strength. Diversifying trade partners and signing new deals can only go so far if underlying vulnerabilities persist. The most fundamental question is one Africans are increasingly posing to themselves: What would it take to truly stand on our own feet?

The answers usually begin at home. Stronger institutions, better infrastructure, and skilled human capital are the foundation of any self-sufficient economy. For Africa to negotiate as an equal on the world stage, it needs capable states that can deliver public goods and foster an environment where domestic and foreign businesses can thrive. This means tackling everything from corruption and bureaucratic inefficiency to gaps in education and technology. It means investing in roads, ports, power grids, and internet bandwidth that connect African producers with African consumers. It also means nurturing local entrepreneurship and industry, so that value is added within Africa rather than overseas. As long as African countries primarily export raw minerals or crude oil and import the finished electronics, machinery, and processed foods they consume, they will remain at the mercy of external price swings and foreign suppliers.

Consider the stark reality: many African economies are still overly dependent on a narrow range of commodity exports���whether it���s oil in Nigeria, copper in Zambia, coffee in Ethiopia, or cocoa in C��te d���Ivoire. This makes them extremely vulnerable to global market fluctuations and leaves them with little bargaining power. Breaking out of that pattern requires deliberate strategy. Governments might, for example, incentivize the growth of local agro-processing industries, so coffee and cashew nuts are roasted and packaged in Africa rather than exported raw. Or they might invest in mineral refining and battery manufacturing at home to climb up the value chain from just mining cobalt or lithium. Some of this is already happening: Rwanda and Ghana have begun processing more of their minerals locally, and Kenya has nurtured a booming tech sector dubbed the ���Silicon Savannah.��� But scaling these successes across the continent is the challenge ahead.

Reimagining Africa���s role in the global economy also requires a shift in mindset. For too long, the focus has been on attracting foreign aid and foreign investment as the primary drivers of development. This often meant tailoring policies to please donors or multinational corporations, sometimes at the expense of nurturing domestic capacity. Now, a new generation of thinkers and leaders is emphasizing build your own over beggar thy neighbor���the essence being that aid can only ever be a stopgap; real wealth comes from productive economies, not perpetual assistance. This perspective doesn���t reject globalization; rather, it seeks to engage on Africa���s terms. It���s about creating the conditions where African nations can engage in trade not as junior partners competing mainly on low wages or raw materials, but as equal players offering competitive industries and innovation.

None of this is easy. The road to true economic sovereignty is long and complex, and progress will be measured in years, if not decades. There will be setbacks and compromises. In the near term, African governments must still contend with external pressures���whether it���s negotiating debt relief with Chinese banks, haggling over trade terms with Europe, or managing the fallout of US policy shifts. Globalization is not going away, and interdependence is a reality. The goal, however, is to reshape that interdependence into a healthier form���one where Africa is not a passive recipient but an active shaper of global norms and networks.

What might that look like in practice? It could include steps such as strengthening governance and the rule of law to ensure that agreements are transparent and resources���whether aid or revenue���are managed responsibly, reducing opportunities for foreign exploitation of instability. Investing in education and skills would equip Africa���s massive youth population to drive the industries of the future, from agribusiness and manufacturing to digital services, rather than relying on expatriate expertise. Developing critical infrastructure���such as highways, ports, rail corridors, and power pools���would prioritize projects that connect African economies to each other and enable local businesses to become more competitive. Fostering entrepreneurship and innovation by supporting small and medium enterprises, start-ups, and research could unlock homegrown solutions and diversify the economic base. These initiatives, many of which are underway to varying degrees, would help build a resilient foundation. Only on such a foundation can Africa truly mitigate the whims of external forces���be it a trade war, an aid cutoff, or a global recession.

Choosing the futureAs Africa moves through this era of transition, one thing is clear: the continent is no longer willing to be a pawn in great power games or a stage for billionaire experiments. There must be a new determination to seize the moment���to leverage the cracks in the old order to build something new and more equitable. The decline of US dominance in Africa���symbolized by Trump���s retreat���has, paradoxically, given African leaders more room to assert themselves. They must actively seek new alliances while also being careful not to jump from the frying pan into the fire of neocolonialism. They must double down on regional solutions like AfCFTA, even as they court outside investors to create jobs.

There is, of course, a long way to go. Africa���s share of global trade remains tiny, and its growing economies are still vulnerable to shocks beyond their control. Setbacks such as the COVID-19 pandemic and the Ukraine war���s ripple effects on food and fuel prices have illustrated how global crises hit African countries hard. The task of building resilience is urgent. This means not only economic diversification, but also strategic diplomacy: African countries must be represented in international forums where decisions about trade rules, climate action, and technology governance are made. Encouragingly, we see more African voices in the G20, the World Trade Organization, and other bodies, pushing for reforms that consider developing world interests���from special drawing rights in financial crises to waiver of vaccine patents.

In the end, the question is not simply whether a world with less US influence is good or bad for Africa. Rather, it���s how Africa can respond to a world of many powers and actors in a way that serves its people���s interests. If the US retreat leads to a scramble where China, Europe, Russia, and private companies all vie for influence, Africa can either be the prize or set the terms of engagement. The difference lies in preparation and unity. African nations will benefit by presenting a coherent voice where possible���for instance, bargaining as a bloc on trade issues���and by insisting on reciprocity and respect in all partnerships.

The coming years will test Africa���s resolve and creativity. Will leaders capitalize on this turning point to implement the tough reforms needed for genuine independence? Will Africa���s elites invest at home or continue capital flight abroad? Will regional solidarity overcome old rivalries to make initiatives like AfCFTA succeed? These are open questions.

What is certain is that the old patterns of dependency have been disrupted. The ���business as usual��� of relying on Washington���s favor or Beijing���s loans is being questioned as never before. A new generation of Africans is acutely aware of their nations��� fragile gains and is impatient for a more secure future. They seek a future where Africa engages with the world on its own terms���harnessing global opportunities but not beholden to any single foreign agenda.

Africa���s pursuit of economic sovereignty in this changing landscape is not just an African story; it is a global one. It will help define the 21st-century economic order. If successful, it could lift hundreds of millions out of poverty and open a new chapter of shared prosperity. If it falters, we may simply see a reshuffling of masters. The stakes could not be higher. But as the saying goes, crisis is opportunity. Africa now has the chance���hard-won and fraught with risks though it may be���to redefine its relationship with the world and ensure that ���partnership��� is not just a euphemism for dependency, but a pathway to true autonomy.

June 3, 2025

The resurgence of Benin sound

Still from "Laho II" music video by Shallipopi.

Still from "Laho II" music video by Shallipopi. I remember being 10, sitting in the backseat of my uncle���s light green Benz, the fabric seats already sticky from the day���s heat. The cassette deck crackled with some high-pitched, nasal melody���Benin music. My uncle sang along in a blend of pidgin and something older, deeper: words I didn���t understand as I don���t speak Benin, but the Ika language.

I had no idea that decades later this music, this energy, would resurface in my playlist, not through old tapes but through Spotify���s algorithm, disguised in trap drums and 808s. Yet here we are: Benin music is back, retooled, remixed, and reimagined by a new generation of artists like Rema and Shallipopi.

Rema has always been a mystery to the mainstream. You can���t quite box him in: not fully Afrobeats, not fully alt��, not pop in the traditional sense. And, buried within his genre-bending sound is a spiritual fidelity to Benin heritage. Listen closely to ���Woman��� or ���Azaman,��� and you���ll hear the cadence, the syncopated rhythms that echo the traditional Benin festivals. The voice modulation, the chants, they are not accidents. They are echoes of ivory masks and coral beads.

But it is Shallipopi, or Crown Uzama, if we are calling royalty by name, who wears Benin like regalia. He doesn���t just make music; he makes street anthems baptized in Oba bloodlines. Words like evian on “Elon Musk” and “Laho” aren���t mere slang, they���re sonic fingerprints of a cultural resurgence. Aza, which many now recognize as shorthand for account numbers, has a deeper, older Benin etymology. It���s a reminder that our language has always traveled, often without our permission, and is now quietly inserting itself into Nigeria���s wider cultural lexicon.

Shallipopi���s success, his rise from TikTok snippets to nationwide acclaim, is also an ethnographic case study. For the first time in years, street culture is looking southward, beyond Lagos, past the Yoruba mainstream, into the spiritual and linguistic reservoirs of Edo State. Unlike older iterations of regional pride that stayed hyperlocal, this one is unapologetically national.

Interestingly, the resurgence isn���t only happening at the top. Enter 2Rymce, the newest voice on the block, whose most popular track, ���Respect Your Elders,��� plays like both a demand and a confession. The beat carries the DNA of traditional Benin drumming but is layered with futuristic synths. There���s an urgency in his voice, a reminder that youth doesn���t mean amnesia. He sings like someone who knows history is both a burden and a blueprint.

When I first heard ���Respect Your Elders,��� I paused. Not simply because of the beat, but because of the audacity. In an age where virality is often purchased through parody or profanity, here was someone invoking tradition, not as nostalgia, but as confrontation. The song reminded me of something beautiful and buoyant. It reminded me that culture isn���t static; it adapts, it shapeshifts. And, in music it roars back to life.

This new wave: Rema���s haunting falsettos, Shallipopi���s coated tongue, 2Rymce���s ancestral militancy, is not just musical. It’s a cultural restoration. It���s a rejection of the idea that only Lagos or Accra, or Jozi has the right to narrate urban cool. It is Benin City standing tall, not with borrowed sounds but with its lexicon and lore.

Language is always the first to go when cultures are colonized or forgotten. Interestingly, our words are returning. Azaman is no longer just a street chant; it���s being echoed in Twitter spaces. Laho, once an inside joke, is now a viral TikTok sound across continents and influencer captions. We���re witnessing a linguistic osmosis; Benin words slipping through the seams of Nigerian pop culture like smoke under a door.

And maybe that���s what makes this moment beautiful. It���s not loud or performative. It���s not a government-sponsored rebrand or a heritage campaign. It���s kids in Uselu making beats with FL Studio. It���s producers blending ancestral percussion with Western plugins. It���s street boys in secondhand drip rapping in proverbs their fathers spoke. It���s culture, surviving not in museums but in clubs and car speakers.

I���m not romanticizing the past. Benin music of old wasn���t always accessible. The tapes were long. The production was thin. The messages, heavy, but there was dignity in it; dignity in singing your mother tongue, dignity in naming your gods. That dignity is returning.

And so, when I see Shallipopi on stage at Homecoming Festival or hear Rema get a crowd in Berlin to chant Benin slang, I smile, because maybe, just maybe, the child in the backseat of the Benz knew this would happen. That someday, his city���s sound would no longer need validation. It would simply be.

June 2, 2025

Fighting for the waste commons

Image �� Rosalind Fredericks.

Image �� Rosalind Fredericks. An army of bulldozers is currently in the process of leveling a portion of one of Africa���s largest waste dumps. The Mbeubeuss dump has been the sole repository for household waste in Dakar, Senegal, since 1968 and now sprawls across 115 hectares���a 70-foot-high mountain of refuse just a stone���s throw from Dakar���s bucolic coastline. Mbeubeuss has employed thousands of people for decades and is at the heart of a sophisticated recycling economy. Officially, around 2000 people currently earn their livelihoods there. They are now anxious about the future as a World Bank-funded government project to close the dump gathers steam. The vast majority will lose their jobs as waste picking is outlawed in the coming months or year. The scene unfolding in Dakar is not unique; shuttering open-air dumps is a fraught approach to modernizing cities worldwide. The waste pickers of Dakar join in a chorus of global waste picker groups resisting dispossession and asserting their role in alternative environmental futures.

The particular area that is currently being cleared is known as Gouye Gi or ���Baobab tree,����� the oldest settlement on the dump. This is generally the territory of the waste pickers from Dakar, many of whom have been working at Mbeubeuss for 40 or 50�� years. Even though the project to transform the dump has been underway for a few years, the process has been extremely tense, and the waste pickers have major concerns about how it is unfolding. Eliminating waste picking and enclosing recycling economies will be devastating to the tens of thousands of people who rely on revenue from the dump. The proposed diversion of food waste to a composting center would be especially catastrophic for the minority Christian women who collect food waste on the dump to feed their pigs and the whole nearby neighborhood that survives on the pork economy.

Though they support efforts to remediate the dump���s negative impacts and scale up recycling operations, the waste pickers of Mbeubeuss are mounting a politics of refusal to be erased by what they consider to be a grab of resources they hold in common and value they have constructed over decades. Their long-running association, Bokk Diom (���Shared Dignity��� in Wolof), is organizing to legitimize their expertise and stake claims to a dump future that is both good for the environment and the working poor. They have formed a workers��� cooperative and labor union to earn legal recognition and have mounted a series of protests. Their rally in May 2023 stopped all trucks from entering Mbeubeuss, bringing waste management in the capital city to a standstill. Then, a group of youngsters formed a new group at the start of 2025 called ���Mbeubeuss Gaza��� and refused to move as the state began clearing their settlements. In February, seventeen waste pickers were arrested in a scuffle with the police that involved tear gas being used against waste pickers. The police were able to scare them away, and the area was cleared for the construction taking place right now, but it���s only a matter of time before there are more acts of refusal.

This struggle over the controversial closure of Dakar���s waste dump is the subject of my recently released documentary film, The Waste Commons. The film was produced in close collaboration with Bokk Diom and Sarita West of Alchemy Films, and draws on my ethnographic research at the dump since 2016. At the heart of the film and the waste pickers��� movement are Adja and Zidane, two charismatic waste pickers who are emerging as leaders contesting the erasure of their community. Adja is a divorced mother from Dakar specializing in plastics. Zidane, who hails from the country���s interior, supports his two families through sales of used shoes. They represent the central demographics at the dump���the urban poor rendered superfluous to the city���s growth engines and the rural poor fleeing collapsing agricultural economies bearing the brunt of environmental change. Both are finding their voice in arguing for their rights to waste within the tense negotiations surrounding the future of their very way of life. In Adja���s words, ���Waste has given me an honorable life. If they were to close the dump today, I would be in despair.��� Adja and Zidane���s testimonies reflect the paradoxes of urban marginality, where the urban poor have no other choice but to carve out a livelihood through other people���s waste. They both find deep solace in their spirituality and solidarity with other waste pickers, and they take enormous pride in their work as environmental stewards.

It is estimated that two percent of urban residents in developing countries forge livelihoods through waste picking. As the chasm widens between the rich and the poor and the production of waste expands exponentially, the reliance of the global poor on recycling is intensifying. In the era of climate crisis, many of the world���s poor, displaced by environmental change, find refuge in recycling economies, which also mitigate the negative effects of breakneck consumption. However, despite providing important environmental services, waste pickers are often treated as disposable. The story of the Mbeubeuss waste pickers is a story that is unfolding all over the world.

Wastescapes across the global North and South are emerging as new commodity frontiers and targets of enclosure and dispossession as more powerful actors attempt to grab the value forged by informal recyclers. Long a reviled space of refuge for the city���s most marginalized, Mbeubeuss is now a key target in the pursuit of modernist development in Senegal. With all recyclables diverted to the state-owned facilities, sorting and recycling contracts will likely go to big international waste management companies, like has been the case in other settings���including, perhaps most famously, in Cairo. Given the dearth of substantive proposals to remediate the dump���s impact on the neighboring environment, the upgrade appears as just the latest element of a bourgeois environmental agenda that is aimed at serving the city���s elites and tourist economy more than making real environmental improvements or serving the poor. It begs the question: Is there a vision of urban modernization that is not a bulldozer to the poor and their vibrant informal economies?

As we travel across the dump and beyond with these waste pickers in the film, we see how, as Zidane puts it, ���Mbeubeuss is a mirror of the city.��� Far from a realm of chaos, the dump is an organized archive of Senegal���s postcolonial history and the waste pickers its careful archivists, cataloging, translating, and making valuable the afterlives of urban living. The rhetoric of state and World Bank officials in fancy office buildings, celebrating how the remodeled dumpsite will serve as a model for ���promoting ecological tourism,��� is contrasted with waste picker strategy sessions hammered out in dusty shacks on top of the garbage mountain. Adja, Zidane, and their colleagues travel internationally to network with other waste pickers and contribute to discussions regarding the global plastics treaty.

Along the way, they learn of inspiring battles that are being waged���and won���all over the world by waste pickers to defend their rights to the waste commons. For instance, reclaimers at the Marie Louise landfill in Soweto, South Africa, were able to retain their right to recycling economies through a legal battle they won against the Johannesburg Council. In Montevideo, Uruguay, waste pickers (clasificadores) have made significant progress in defending their rights to waste and improving their working conditions through cooperatives and union organizing. For their part, Mbeubeuss waste pickers continue to assert their proposal for a different future of Mbeubeuss that would honor their expertise, protect their bodies and communities from harm, and, rather than replace their labor with machines, scale up their recycling operations.

At the end of the day, will Dakar���s dump closure provide a model for how to integrate waste pickers into the modernization of the city, or another catastrophic example of treating the poor as disposable?

The Waste Commons film can be seen at festivals all over the world, including its US premiere on June 5 at the New York Independent Film Festival, as well as an upcoming advocacy screening at the Blaise Senghor Cultural Center in Dakar on July 2.

May 30, 2025

Hope after liberation

Still from No Simple Way Home �� 2022.

Still from No Simple Way Home �� 2022. In one of the final scenes of the film No Simple Way Home, Akuol de Mabior sits inside a vehicle, describing the people along the roadside as the car drives by. There, individuals selling tea strive to make a living. These are the ones who, as she puts it, hold everything together and prevent it all from collapsing. The film by the South Sudanese director was showcased this winter at the Barcelona Contemporary Culture Centre (CCCB) as part of a series organized with support from the Open University of Catalonia (UOC). Both institutions are hosting Zimbabwean writer Tsitsi Dangarembga through a literary residency program, during which she has curated a showcase of work by two rising African women filmmakers: the South Sudanese Akuol de Mabior and South African Milisuthando Bongela.

Akuol de Mabior���s film, which premiered at the 2022 Berlin International Film Festival, tells a deeply personal story. Born in Cuba in 1989 and raised in Nairobi, she is the daughter of John Garang and Rebecca Nyandeng De Mabior, a couple pivotal to South Sudan���s independence struggle. Garang died in 2006, five years before the country formally became independent in 2011. Today, South Sudan grapples with rebuilding itself amid a fragile peace agreement and cyclical internal conflicts. Her mother is one of the country���s five vice-presidents, the result of a complex political system not dissimilar to Bosnia, which serves primarily to maintain a fragile peace rather than offer services to South Sudanese citizens.

In recent weeks, that peace has been looking increasingly fragile, as two of the most powerful figures in government, President Salva Kiir and Vice President Riek Machar, appear on the brink of conflict again. The war in Sudan has also impeded the country���s largest source of revenue, oil exports, after a pipeline burst due to fighting near Khartoum. The nation���s latest currency devaluation has plunged most citizens���dependent on the informal economy���into deeper hardship. The South Sudanese pound lost an astonishing 64 percent of its value against the USD in 2024.

Speaking to Jaume Portell, Akuol de Mabior discusses her filmmaking, the quest for identity and belonging, her mother���s difficult decision to join the South Sudanese government, and the sacrifices of a generation now wondering whether their fight for liberation from Sudan was worth the cost.

Jaume Portell Ca��oHow do people manage to survive in an economy where nothing seems to be working?

Akuol de MabiorI think of them as experts. They need to know a lot to run their business. I made a film about the informal sector: It���s on Al Jazeera, and it���s called Hidden Strength. One character in the film is a Juba native in her 50s, born and raised there. She owns a restaurant that she has kept running through war, peace, and war again, and then peace once more. She always reopens it. For me, the biggest source of hope and change are people like this.

She has created systems so that ���when it���s really bad, this is what I serve.��� Whatever happens, she will be sitting at her counter. I wanted to call the film The Shop Counter Revolution.

Jaume Portell Ca��oYou���d make a great journalist with headlines like that.

Akuol de MabiorWhen we interviewed her, she spoke about the systems that helped her deal with all that madness. They really do have deep knowledge that people undervalue.

They���re organized, but when the value of the currency is dropped in a single day, their savings are decimated. It���s all they had���they were saving in the local currency, so they were optimistic, they were there, they were invested, and��� you are losing that person. And this has happened maybe twice or three times [in South Sudan]. We were speaking with Tsitsi [Dangarembga] about continuity. So, if you have a currency collapse because some guy decided yesterday, by decree, that we’re going to change everything, then you have broken continuity.

We were talking about how there���s this tendency to make sweeping changes. Because that feels good: ���This person is going to save us.��� But probably what really changes things is continuity: Somebody like Mama Zahra, the woman who owns that restaurant. She���s an institution. There���s even a place called Medan Zahra [Mama Zahra Square], because everybody knows this woman who continues to open her shop. That level of continuity is what creates a big change.

Jaume Portell Ca��oI had never thought about it this way: A major currency devaluation is like a betrayal. You are telling your own people, ���You should have hoarded dollars.���

Akuol de MabiorOr invested elsewhere. The most optimistic, the most loyal to the place, are the ones who suffer the most. The person who is the most optimistic, the most invested, and who cares the most about the community���that person is constantly heartbroken.

Jaume Portell Ca��oWhat���s the relationship between the South Sudanese people and the state?

Akuol de MabiorI can speak from observation, from working and filming in South Sudan. I don���t want this idea that I���m representative of South Sudanese women, because my experience is not representative.

It���s a sensitive question. People are not that free to criticize. If you���re born of a liberation struggle, there���s sort of this idea: This person or this movement will deliver us to the promised land, and that requires leadership. You must be in that mentality to sacrifice so much for freedom as a concept. So, I think there���s still hope around the leadership, even as people keep being heartbroken and things keep falling apart. That mindset from the liberation struggle makes you continue being hopeful. I think people are also angry, but silent.

Jaume Portell Ca��oA liberation struggle is always about a future expectation. Independence, managing a country, is about reality. Do you think there is a clash between these two concepts? In a way, it looks like South Sudan is living what many countries on the rest of the continent experienced in the 1970s or 1980s. Do you think you will be able to avoid the path other countries followed back then?

Akuol de MabiorThat was the big hope in 2011. The problem is that a lot of the major catastrophes we���ve experienced in our short history have to do with power struggles within the leadership. Then there���s a sort of mobilization of communities: ���This is my community, so they support me,��� and they support what I decided today, which is, ���I don���t like this guy anymore.��� Civil wars start in leadership.

Jaume Portell Ca��oHow has your relationship with South Sudan evolved since the film was released?

Akuol de MabiorI know a lot more about South Sudan since finishing making the film. Of course, I still don���t consider myself to be an authority on the country. I���ve learned just from being there and talking to people. I did another short film that meant we were on an old barge, and we went eight hours up the Nile.

I went into making the film without a hypothesis. I was looking to find if there is anything that we can be hopeful about, even as we���ve experienced catastrophic problems. The one conclusion that I kind of came to was this informal sector: We have all these tea shops in Juba and in South Sudan. If you���ve ever been to Juba, if you are paying attention, you will see all these blue chairs everywhere, with a lady serving tea and people drinking tea on the road. I spoke to one young woman who owns one of these tea shops, and she was able to put herself through school and bring an income for her family.

One recurring element in the film is the relentless flooding, which grows increasingly severe. Even in that apocalyptic setting, when it���s flooded and it looks like the end of the world, you���ll still see a woman coming to stack up all her chairs and open her shop. Of course, nobody should have to live like that, but the people who have the heart to still go and open the shop in a situation like this���that���s where I would point my camera.

Jaume Portell Ca��oLet���s discuss the diaspora, an essential subject of the film No Simple Way Home. How does it feel to say, ���I���m from a place I���ve never been to���?

Akuol de MabiorIn a South Sudanese context, I think part of our identity comes from the liberation struggle: We come from a country [Sudan] where, as southerners, we were not treated well. You are duty-bound to your country because so many people sacrificed: You are told about that, you learn about those stories. So, you need to go home to your country and help because all these people were sacrificed for this. That���s a powerful, strong narrative: People have sacrificed a lot for you to be able to call yourself South Sudanese.

There���s some goodness in this sense of duty, but it can also make people not ask enough questions: You are supposed to just love your country, to just feel patriotism in your heart.

Jaume Portell Ca��oSome people think that patriotism equals submission.

Akuol de MabiorIt���s like a religious experience. You are just supposed to surrender and not ask too many questions. I just want to know if I can get a job, where I am going to live, what the schools are like, what the living standards are, practical things. What���s the price of water?

We have a unifying narrative, and people might feel invested in coming home���even if it���s a home they have never been to. You could be living in a neighbourhood in Australia and really feel connected to South Sudan, even if you���ve never been there. There���s a goodness to it, but then we can sometimes become very romantic, and it can be a disillusioning pull.

Jaume Portell Ca��oDo you think that some of these people choose South Sudan or their African country of origin because they are not accepted in the host country?

Akuol de MabiorI grew up in Kenya, and we did feel that we were not Kenyan; but I���m sure it was not as bad as in Australia, Egypt, or the north of Sudan. After filming, I also realized that building a home and the changing sense of home are universal things: Everybody has to figure out where their home is. But if you���re unsettled in your national identity because of your circumstances, the tendency is to think that you’re the only one who has no sense of home.

Jaume Portell Ca��oThere���s a moment in the film where a woman asks you if you speak Dinka, and you say, ���I don���t speak it, but I understand it.��� What is the relationship between the South Sudanese who have grown up there and stayed there, and the South Sudanese diaspora?

Akuol de MabiorThere have always been a lot of internally displaced people, so for those who stayed, it would have been extremely challenging to remain continuously. There might be a tension and a sense of, ���You���ve been comfortable out there this whole time, and now you come back, and you want to tell me what it means to be where I���m from, me who has been here the whole time.���

Then, there is a tension between people who stayed closer and engaged somehow, and those who went and lived in the US or Australia, and either didn���t come back or came back rarely. I think it���s unfortunate: There should be more grace for both the people who stayed and the people who left, because it���s rough. I think it���s fraught because both groups of people could make valid points about their choices.

Jaume Portell Ca��oIn a sense, No Simple Way Home is also a film about your mother, Rebecca de Mabior. What struck me most was the profound loneliness the story conveys. Here is a woman���alongside her comrade and husband, John Garang���committing her life to building a nation. They dedicate decades to this immense struggle. Yet, when freedom is finally attained, she is on her own.

Akuol de MabiorShe always worries that it was all a waste. ���Was this all for nothing?��� She says it all the time. She���s very vocal about it. She asks herself: Did we do all of this and make all these sacrifices? Did all these people make all these sacrifices and die? And has it all been for nothing? She also sees herself as having sacrificed her husband to this cause, the ultimate sacrifice. I don���t think she���s answered that question; that���s the weight she carries.

Jaume Portell Ca��oWhy do you think she was offered the vice presidency?

Akuol de MabiorTechnically, it���s in the peace agreement of 2018. There was a decision to give positions to the disagreeing parties, and she was lumped with what they call the former detainees���a group of people who were arrested. She spoke against anything being done to them. These are people she sees as comrades, who were close to my father and a big part of the movement.

So, she���s one of five vice presidents. When I interviewed her, she said that it was not an easy yes, because things are messy and dangerous. But she had a sense that she could help keep the peace between people who don���t always see eye to eye.

Jaume Portell Ca��oSo, her role is essentially that of a peacemaker.

Akuol de MabiorThat���s what pushed her to say, ���OK, fine,��� because we can���t afford another war. In a screening I did in San Francisco, one woman asked, ���Why would your mother join such a corrupt government?���

It was a good question. I said that it was not an easy yes, but she felt that saying no might have a worse outcome. Do you make decisions because the optics are good? Yes, if she were on the outside, she could be in the opposition and say, ���Look how bad they are,��� and look good. But there was much more to that decision. It was not an easy yes; she doesn���t covet political power.

Jaume Portell Ca��oWhat kind of films do you hope to make in the future?

Akuol de MabiorI would love to do an Africa-wide series on the informal sector���the people who find ways to make things function. I���m also working on an adaptation of a Sudanese novel with some producers based in Paris. Additionally, I���ve been preparing another film about a politician for a few years now.

That���s been an ongoing and difficult project that I really hope to deliver. I don���t want to be making an expos��, and I hope to avoid propaganda. I always have to add this caveat: I want to humanize African leadership, but that���s not to say we should forgive mistakes.

We tend to sanctify or demonize. Mandela is basically a saint, right? And then we have our demons���monsters who are outside of humanity. I see it as the job of a documentarian to bring all those experiences into our shared humanity.

Sunday service on two wheels

During the week, the streets of Braamfontein and the CBD are abuzz with Joburgers on the

May 29, 2025

What to do about Kenya’s femicide problem?

Anti-femicide march in Nairobi. Image �� Innocent Onyango.

Anti-femicide march in Nairobi. Image �� Innocent Onyango. When I moved to South Africa in 2021, the country ranked among the deadliest places in the world to be a woman. With one of the highest femicide rates globally, the government of South Africa had declared a femicide crisis at the end of 2019. At the time of the declaration, press coverage was dominated by the rape and murder of 19-year-old university student Uyinene Mrwetyana, who was killed during a visit to the post office by postal worker Luyanda Botha.

Data from the South African Police Service for 2018/2019 would later show that one woman was murdered every three hours. Worried about my safety, a friend in Nairobi offered to move me down: ���Just for a few weeks,��� she reasoned, ���till you get settled in.���