Sarahbeth Caplin's Blog, page 32

August 28, 2016

Hello, Sober September

If you’ve read my newest memoir, you may recall a few chapters detailing my complicated relationship with alcohol. “Complicated relationship” feels more appropriate than the ultra-clinical diagnosis of “alcoholism,” especially because this struggle has come and gone in waves. Understandably, it was at its worst when my father died, and in the months before. This time two years ago, I wasn’t going to bed sober anymore. First I needed it to sleep, then to calm down, and eventually to “check out.” My childhood home had turned into a home hospice, and misery was everywhere I went.

If you’ve read my newest memoir, you may recall a few chapters detailing my complicated relationship with alcohol. “Complicated relationship” feels more appropriate than the ultra-clinical diagnosis of “alcoholism,” especially because this struggle has come and gone in waves. Understandably, it was at its worst when my father died, and in the months before. This time two years ago, I wasn’t going to bed sober anymore. First I needed it to sleep, then to calm down, and eventually to “check out.” My childhood home had turned into a home hospice, and misery was everywhere I went.

Interestingly enough, I was sober the morning my father died. I was sober when I called my then-fiancé, who was unable to leave his job several states away, to tell him that he needed to come home. And I was sober when I spoke at the funeral, which I didn’t think I’d be capable of doing, sober or otherwise.

Having gotten through the worst of the worst of times without it, maybe I’ve already proven to myself that I’m strong enough to cope better, to admit when I need help. I’m getting better at saying to my husband “I’m having another episode,” referring to a depressive episode, and he knows to keep watch. To check in with me. To be there. It seems cliché, but it’s true: I don’t think I could have gotten through the most challenging days without him.

Christian circles would refer to my husband’s role in this as being an “accountability partner.” In reality, though, it feels more like “babysitter.” I’m a grown woman, and sometimes I rely on other people to protect me the way a parent protects a toddler who doesn’t know she’s playing too close to the deep end of the pool. They are the ones who swoop in when I’m about to fall. Despite feeling childish about needing intervention, I know now that asking for help is really one of the most adult things I can do.

My journals went neglected for That Summer, the last one of my father’s life. Maybe that’s part of why I started to slip: I needed to write about what was going on as much as I needed my antidepressants. Writing, for me, is an antidepressant. Most importantly, it’s an exercise that helps keep me stay present, an expression that my therapist uses a lot – “What can you do to help Stay Present?” – and I know it’s working when it hurts.

Funny, I drank to escape feeling the depth of the loss, the slice of the painful memories, and here I am summoning them with a pen. But that’s life: feeling, remembering. It’s part of being alive. The human experience hurts beautifully.

I have learned there is a difference between sobriety and simply not drinking. Sobriety, for me, is realizing I don’t need a substance to escape anymore. “Not drinking” is more like white-knuckling my way through, wanting a drink but knowing I shouldn’t, because it’s bad. Obviously, sobriety is the thing that is worth working for, though not drinking is surely an improvement.

Being the last week of August, I’m starting to get a little antsy. The month of September will probably always be overshadowed by my father’s death, hence why it’s now Sober September in my mind (and I find myself humming Green Day’s “Wake Me Up When September Ends” lately).

I don’t like the expression “lost the battle” in reference to cancer. While that’s technically what happened, my father wasn’t a person who could be easily defeated, and I don’t want to be, either. It has occurred to me that, while it may pale in comparison to the severity of cancer, my battle for sobriety is something that reminds me whose daughter I am (I refuse to say “was”). And that’s how I know I am stronger than this; stronger than I give myself credit for.

Filed under: Uncategorized, Writing & Publishing Tagged: Author Sarahbeth Caplin, cancer, grief, self-care, Writing

August 26, 2016

Why are we so easily offended?

The stereotype used to be that liberals were the ones easily offended by everything, and were politically correct to a fault. But lately it seems the tables are turning. In my world, both online and off, it is the conservatives who are the easily offended and make mountains out of tiny mustard seeds when there’s absolutely no need for it.

I ask myself often, Is this really what Christianity is all about, or is this just the Christian-tainted culture water in which I swim? I can’t imagine the early Christians bickering about the context of curse words or satirical Facebook memes when persecution and death were so imminent. At some point in evangelical history, aversion or disagreement on faith-related issues became perceived as a threat. For many people, the best way to protect their faith from crumbling like a house of cards is to surround themselves with like-minded people who never challenge their ideals. For many, it’s a virtuous act to avoid the world beyond their bubble.

#NotAllChristians

I wish I didn’t have to keep repeating “This message does not apply to all Christians,” but inevitably, someone will feel compelled to point out that #NotAllChristians act this way. And that helps proves my point: there are enough Christians in the fold to whom the criticism applies. If you feel offended, perhaps that’s a hint to examine your own heart. Why is it so hard for us to own up to our collective mistakes? Why is it so hard to acknowledge that we do have quite a few people in our midst who do the exact opposite of everything Jesus said to do, and call out hypocrisy for what it is?

A meme like this, for example, is not an indictment of everyone who attends a megachurch (there’s nothing wrong with that) but rather a call to keep our priorities in order (source):

Shortly after one of my seminary friends shared this on Facebook, the comment thread blew up with responses from other Christians about how offensive it was, that clearly my Christian friend had never been to their megachurch, etc. In other words, they completely missed the point. There should be “mega homeless shelters,” but in the midst of arguing the merits of megachurches and the people who attend them, the homeless people in question were completely forgotten.

Another Christian friend shared this recently (source):

It’s possible that the outcry from this one comes from an inability to distinguish satire on the internet, which is why I firmly believe that Facebook should invest in a sarcasm font over another ‘like’ button. Satire, as you may know, is intended to point out a problem – in this case, an ethical problem – using humor. We know there are Christians who act like this. They’re the kind who want drug tests administered before families can go on welfare when Jesus did no such thing (or whatever a first-century equivalent might be). They want the “good” families, with both a mother and a father, who are married, to receive benefits, and to hell with everyone else. If you are straight, part of a traditional nuclear family, and vote a certain way, you gain all the Jesus Points.

What both amuses and saddens me is that the Christians who were so offended by this meme were acting just like the Pharisees that Jesus was trying to reach. People always ask me what it is about Christianity that appealed to me as a Jew, and one item on that list is just how much of a mensch Jesus was. He acted boldly and used strong words when necessary, knowing he would royally piss people off. His methods – flipping over tables, responding to questions with more questions – might be considered flippant and even rude by our standards. Read in the context of his time, Jesus’ actions were appalling, depending on which social class you belonged to.

Through a glass darkly

Here’s the thing: sometimes, harsh words (or memes in this case) are necessary to get a point across. My theory is that those who are most offended might be the ones for whom the meme was intended. I strongly encourage you to ask yourself why it is you might be offended. Does it upset you when Christians as a whole are portrayed negatively? Or are you embarrassed at being called out for behavior that you are guilty of practicing?

If it’s the former, that’s understandable. No one likes to be insulted, especially when you know yourself well enough to know you don’t personally deserve it. It’s important to keep in mind, though, that one denomination’s truth is another denomination’s heresy. Today we’re ashamed of the Christians who condoned slavery, but they were utterly convinced they were doing God’s work – and the abolitionists were the sinful ones.

Christians have hurt people. Christians have been wrong about a number of things. Those are facts, and it’s a mark of maturity to be able to own it.

Shaking off the dust

Growing up Jewish, I was misunderstood quite a bit, so much that I eventually got used to being asked if Moses was the “Jewish Jesus” and if Jews had a Santa Claus equivalent. Those questions (let’s admit, they’re pretty dumb) didn’t exactly stop in elementary school. They were asked of me in college as well. But putting up with that ignorance gave me a priceless gift: thick skin.

You know what’s funny? When I became a Christian, I thought it was required to be insulted at every anti-Christian remark, because Jesus warned that his disciples should expect persecution. I wrote what is now a pretty embarrassing editorial for my school paper – and sadly, one that got some of the most page views online – about how an ad in the student center from the Freethinkers club, “Smile, there probably isn’t a god,” was bonafide Christian persecution on campus. The nonreligious students bashed it to pieces on the web while my inbox overflowed with messages from Christian students and faculty alike, praising me for my bravery. It was all so bewildering. Today, though I still admire College Sarahbeth’s pluck, I’d want to smack her upside the head for being so naïve.

Over the years, I’ve developed a sense of self-awareness. It’s easier now than it used to be to admit when I’m wrong or guilty of something (though it does kinda depend on what it is I’m wrong or guilty about!). When I see memes like the ones above on Facebook, I know they have nothing to do with me. When I read blog posts by friends of mine who call themselves anti-theists, I’m not offended because I know that religion can hurt, and I know what they’ve been through. Venting can be a critical part of healing.

Today, I have my own faith and don’t feel a need to defend it. I’m aware of what my flaws are, for the most part, and what I need to work on. For all the talk about Christ dwelling in us, Christians are still people, which shouldn’t be difficult to understand. We can love our family members even if we occasionally have to apologize for the things they say or do in public.

Like this post? Check out Confessions of a Jew-ish Skeptic, now available on Amazon.

Stay in touch via Facebook and Twitter.

Filed under: Social Issues, Uncategorized Tagged: Christian culture, Christianity, Controversy, evangelicals, Facebook, Judaism, Seminary, social justice, Spiritual Abuse

August 22, 2016

Fall semester PSA: don’t rape the freshmen (or anyone else)

Original text from my friend Bailey:

Every year, some assholes decide that it’s necessary to post signs across from campus while freshmen are moving in. From “MILFs Drink Free” to “Freshman Daughter Drop-off” to this year’s “Sorority Girl Sign Up,” this behavior is disgusting and unacceptable. But this right here. This is why I love my school. The first two weeks on campus are the most dangerous for a college freshman, and it is during that time frame that a new student is most likely to experience sexual assault. I am so proud of my CSU community for taking a stand against rape supportive culture, starting from the very first day students are on campus.

The first few weeks of fall semester make me nostalgic. As an old, married grad student, the thrill of being on a new campus looking forward to meeting all kinds of people (read: guys) is pretty much gone. But I remember the build-up of excitement brought on by TV and movies that made college campuses seem like The Place to find yourself and make memories.

I was raped in a college dorm room. That should never have been part of the plan. My perception of college campuses as fun, safe spaces disappeared. I enjoyed college, don’t get me wrong, but by the time I was a senior I wondered how different my experience would have been if I’d said something. If I’d gotten help sooner. I’ll never know.

For anyone still a bit confused on what consent looks like, this is a fabulous example that compares assault to stealing money out of someone’s purse, although it’s a shame that the violation of one person by another cannot be thoroughly understood as wrong by certain minds until put in monetary terms. Well, whatever works.

To echo Bailey, I too am proud to attend a school with a women and gender advocacy program that is both educational and supportive of survivors. From Kendall, another advocate at CSU:

We’re speaking out without any affiliation with any office in particular or any student organization, although most of us have been involved with the different Student Diversity offices during our time at CSU.

We’re speaking out because this problem matters and it effects all of us.

Because we believe survivors.

Because we know that someone will be assaulted or raped during these first few weekends.

Because we care.

I won’t say “Be careful who you go home with” or “Make sure you watch your drink at all times.” You can’t tell potential victims to be responsible for rapists. So I’ll use my platform to say this: don’t rape freshmen. Don’t rape anyone. Don’t rape, period.

Filed under: Feminism, Social Issues Tagged: Feminism, rape culture, self-care, social justice

August 15, 2016

Made for another world, but not like Lewis intended

I took the liberty of removing myself from a Christian blog group today, because I don’t have an “off” button when responding to theological viewpoints I find triggering; particularly the “God saved me from” rhetoric. I figured it was only a matter of time before the moderators removed me anyway.

Maybe it’s impossible to critique a religious viewpoint without sounding as if you are critiquing the person holding it, because faith is integral to a Christian’s identity. I get that. And the internet isn’t always the best venue for these discussions, when tone and inflection are lost behind a screen. I never know if the fault is the group itself, for being unable to handle dissension and disagreement no matter how politely stated, or if it’s just me, and not coming across as polite as I intend to be.

But even if the issue is me, homogeneity saturates Church culture, particularly evangelical church culture. Introduce yourself at a young adult bible study, and it will, in many cases, be assumed that you hold the same beliefs, attitudes, and convictions as everyone else. This has never been the case in Judaism (the kind I grew up in, anyway). In many, many Christian communities, disagreement can feel like a betrayal: What do you mean it was doctors, not God, who healed my cancer? How dare you.

This is why I read more skeptic blogs than Christian ones these days. They don’t share my faith anymore, but they get where I’m coming from and why I feel the way that I do about certain things. They don’t try to “fix” me with more bible verses and personal testimonies of what God has done for them.

Maybe the problem is that I’m too harsh and insensitive to others’ feelings, too judgmental because I’ve experienced certain things they haven’t, or too self-righteous because I spent ONE WHOLE YEAR at seminary and now I know everything. Whatever it is, one fact remains: because I grew up Jewish, I am automatically at a disadvantage for viewing things the same way that other (most?) Christians do. Old habits are tough to break, but old worldviews installed in childhood are even harder.

It’s not impossible to find community with people who have profoundly different life experiences and viewpoints than I do, but it is difficult. For all the reminders from well-meaning friends that I “just haven’t found my people yet,” it’s sure easy to get burned out trying.

Do I accept that I’ll never completely fit in, and keep my mouth shut? Do I continue being honest about my disagreements at the risk of hurting feelings and being dismissed? Such hard questions. Such desperately needed wisdom.

You know, I originally tattooed the words “Made for another world,” paraphrasing C.S. Lewis, as a way to remind myself that the hardships I face in this world can’t compare to the glory that awaits on the other side. But true to pattern, apparently, I don’t read those words the same way anymore, and that ink is only three years new. But by being born to Jewish parents, I literally was “Made for another world.”

You know, I originally tattooed the words “Made for another world,” paraphrasing C.S. Lewis, as a way to remind myself that the hardships I face in this world can’t compare to the glory that awaits on the other side. But true to pattern, apparently, I don’t read those words the same way anymore, and that ink is only three years new. But by being born to Jewish parents, I literally was “Made for another world.” The years I spent struggling to embrace that fact aren’t over, and the self-made, tongue-in-cheek identifier “ Jew-ish Skeptic ” feels more accurate with every passing day.

Filed under: Theology, Writing & Publishing Tagged: Christian culture, Christianity, Controversy, evangelicals, Facebook, Judaism, Writing

August 11, 2016

A fresh look at the parable of the prodigal son

It must be pretty obvious that I have a soft spot in my heart for the parable of the prodigal son in Luke 15:11-32, seeing as I named my memoir after it.

The parable is about two sons who work for their father. The younger one asks his father for his share of the inheritance ahead of schedule – essentially saying he wishes his father were dead – and then skips town to squander his new wealth on frivolity, while his older brother stays and continues working for his father. When the younger son’s money runs out, he returns home and begs his dad for forgiveness. The twist in the story is that the father immediately welcomes him back, and even throws him a party. This infuriates the older brother, who complains that he did everything that was expected of him and yet he never got a party, much less a fattened calf for a celebratory dinner. His father calmly tells him that his son was lost, and he is rejoicing because now he has been found again.

It’s a beloved story for Christians because it’s a metaphor for God’s love for us: no matter what we do, no matter how much we screw up, he’ll always take us back like that father did.

I read this story a little bit differently. I saw myself as the younger brother, yes, but the “wealth” I squandered was my Jewish education. I “rejected” it all for a social club called Christianity (I’m sure that’s how many people in my life saw it). The end of the parable is a metaphor not just for God’s love for me, but of my parents’ love: they “took me back” (as in, let me continue being their daughter) even though my conversion was confusing and stressful for them. So the twist in my version, then, is that I’m still, in their eyes, a prodigal (more on that in my first memoir’s newest sibling).

I reread that parable again recently as part of an extended study with my small group, based on Timothy Keller’s Prodigal God. Like many stories I grew up reading, this one read differently through the hindsight of the years that separate me Campus Crusade for Christ and seminary, in addition to my father’s death, and a major faith crisis. It’s not the same story for me that it once was.

I reread that parable again recently as part of an extended study with my small group, based on Timothy Keller’s Prodigal God. Like many stories I grew up reading, this one read differently through the hindsight of the years that separate me Campus Crusade for Christ and seminary, in addition to my father’s death, and a major faith crisis. It’s not the same story for me that it once was.

I no longer see myself as the younger brother, I’m the older one.

In Keller’s view, the older brother is like the Pharisees of Jesus’ day. His relationship to his father was based on following the rules, and wasn’t a genuine relationship at all. He was seeking glory for being faithful, and naturally resented his younger brother for shirking his responsibilities and still being treated like a king. Where’s the older brother’s reward for good behavior?

That poor brother, we’re supposed to think. His so-called “relationship” is all performance based.

Here’s the thing, though: I don’t think Big Brother deserves that bad rep entirely. Honestly, think about it: wouldn’t you be pissed off if you did everything that was expected of you – and perhaps then some – in your job, only to find out that the laziest employee on your team got the promotion instead? You might suspect favoritism, since he sure as hell didn’t deserve it. Or maybe he and the boss are sleeping together. Either way, that promotion should have been yours – the one who actually did everything right.

That’s not an unfair reaction. That’s a perfectly understandable one! Not only does the parable highlight the limits of God’s love for us (ie: there aren’t any), it also teaches the necessity of forgiveness. The scorned father had every right to turn his son away and say, “Sorry, you reap what you sow, kid. You can come home, but you’re really going to have to work at earning my trust again.” But he didn’t. He embraced his son with complete and utter gratitude for his return.

Clearly, this story only works on the assumption that the prodigal son was actually repentant. I’m sure he had to be, or else it wouldn’t be in the Bible. But one cannot dispute the fact that Christianity is filled with so. many. unrepentant leaders who still have yet to lose the respect of their congregations. Not Josh Duggar, who molested his sisters and a babysitter. Not the priests hiding from justice under the protection of the Vatican, and Pope Francis, who turns a blind eye. Not Bill Gothard, founder of the sect that the Duggars belong to, who was accused of sexual harassment by thirty-four women.

No, these people still have their book deals, their reality shows, their inspirational memes, and thousands of supporters. Their apologies, if offered at all, are prime examples of not-pologies that essentially say,” I’m sorry you feel hurt,” and not “I’m sorry I did the thing that caused the hurt in the first place, it was very wrong.”

Part of the reason these men still hold power over their followers is because of the unhealthy emphasis on forgiveness: a critical piece of the Prodigal story. It’s unchristian to withhold forgiveness. The father in the parable represents Jesus, and if Jesus did it, then we have to do it, too.

Needless to say, many of us have completely twisted the meaning of this, if we ever understood it at all. See, I did all the “right” things, too. For eight years I attended church, Bible study, small groups, had “quiet times,” sought God’s involvement in every major life decision, and turned down a handful of opportunities to have sex before I got married (that last one made me especially prideful). I took on the role of Kent State’s professional missionary and used my platform as a newspaper columnist to preach to my student body. I even went an extra ten miles and enrolled in seminary after college.

And yet, here I face the worst faith crisis of my life, in which the hooks of doubt are so deeply embedded that I don’t know if I can emerge without permanent disfigurement.

It makes me a little angry when people who have never experienced serious hardship (so it seems from my perspective, anyway), never asked hard questions, act as if they alone hold the Keys of Truth, and anyone who disagrees with them has obviously never been Christian in the first place.

The parable of the prodigal son, then, is about many things: unconditional love, forgiveness, the importance of repentance. But ultimately, it’s a story about all the very human ways we approach God, and about being human, period.

Filed under: Theology Tagged: Author Sarahbeth Caplin, Campus Crusade for Christ, Christian culture, Christianity, Confessions of a Prodigal Daughter, evangelicals, grief, Judaism, memoir, Seminary, Spiritual Abuse, Writing

August 7, 2016

On “faith-shaming”

When my faith starts to wane, sometimes all it takes to bring a glimmer of it back is a glance at my bookshelves. My library is filled with stories of kindred spirits who have walked similar paths, experienced similar struggles, and even had a similar upbringing. These are the pages I turn to for encouragement when the Bible is just too difficult to read, and I need a reminder about what faith can look like in an ordinary, contemporary life, for all its bumpy inconveniences and less than ideal moments.

I also own books that lit me up with the fire of conviction when I needed it – when I believed I was a brave, moral soldier on a college campus filled with heathens looking to eat me alive – that now terrify the daylights out of me. If you aren’t offended or convicted by the same things I am, they say, you’re not really One of Us.

One of us. Part of the tribe. A movement of like-minded people who collectively engage in a practice that blogger John Pavlovitz calls “faith shaming” whenever a member questions the status quo.

As explained in my previous post, the Christian status quo is hardly static, but certain doctrines were prevalent enough in the churches, bible studies, and small groups I’ve attended over the years that led me to believe they were 99% universal: that Jesus is God, that he came to free us from the bondage of sin, and redeem suffering so we can become like God. That last part is the most critical reason I became a Christian: I was looking for a context for suffering that was a bit more hopeful than the tongue-in-cheek “Shit happens” philosophy of the Judaism I grew up in.

For all my doubts about hell being just, my gay friends’ marriages being sinful, and Jesus being the only way to heaven, it’s the redemption piece that keeps me from running away as fast as my legs can carry me when Christians get scary. And we all know a Scary Christian or two…or fifty. Some churches are filled with them. Politics is crawling with them. And with these Scary Christians comes theology that isn’t just scary, but sometimes downright ugly:

I saw this meme on Facebook the other day and probably stared at it for a good two minutes with my jaw hanging open. I’m sure many Christians and former Christians can attest that this kind of “blessed life” does not, did not, match their version of reality. It sure as hell doesn’t resemble mine. I leaned on Jesus in the aftermath of my rape, of my father’s illness, and in the toxic environment of seminary, but according to this theology, if my faith were “real” then I never would have experienced any of those things in the first place. Those Christians in Syria being killed for their faith must have some unacknowledged sin in their lives or something.

The prosperity gospel is not a fringe sect in the United States (take a look at the uber-bestseller The Prayer of Jabez by Bruce Wilkinson, or anything ever written or spoken by Joel Osteen). It baffles me that PG adherents can read the same Bible I’m reading and come to the conclusion that Christianity is glorified Candy Land, I can’t bring myself to “faith shame” them even in my own head.

There’s no one I want to faith-shame more than prosperity gospel proponents.

And yet…

In the end, we all have different ways of coping with suffering. If the promise of a great reward keeps some people from all-consuming anxiety, so be it. Christianity can seem homogenous from the outside looking in as everyone raises their hands while praising and condemning the same things, but I can’t give up the fight to create something uniquely my own, just between me and God.

Like marriage, this relationship will not look like anyone else’s, even if it’s good and healthy. What’s normal in one relationship may not be in another, and yet neither is fundamentally “wrong.”

I probably “faith shame” myself more than anyone else, but the only shame-worthy practice I engage in is measuring the legitimacy of my faith by comparing it to everyone else’s. I have to remind myself daily that there is so much going on inside that I can’t see.

Like this post? Check out Confessions of a Jew-ish Skeptic, now available on Amazon.

Stay in touch via Facebook and Twitter.

Filed under: Theology Tagged: Christian culture, Christianity, evangelicals, Facebook, First World Problems, hell, Judaism, marriage, prosperity gospel, Seminary, social justice, Spiritual Abuse

August 4, 2016

Racial inequality and LGBT rights: these truths will be self-evident?

Slavery as a Theological Crisis by Mark A. Noll is a short, easy-to-read book that demands to be read slowly. Covering 150 years of American history, I recognized so many parallels to evangelical anti-LGBT rhetoric today, it made my head spin. But that’s not all that stood out to me. It’s pretty common for non-Christians to be accused of having relative morality, yet this brief examination of history shows that Christians are just as guilty of this as anyone.

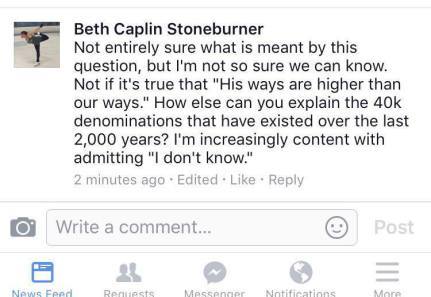

To say that the Bible lacks clarity on anything feels like a confession of heresy. I struggled with writing this thought down in a private journal, let alone saying it out loud in Bible study, and in response to an acquaintance’s Facebook post that asked, “How do we know God’s truth?”

Because I’ve never met a theological question I couldn’t at least take a stab at, I responded with this:

Had this “discussion” happened in person, I might not have been able to disguise my blatant frustration and disappointment with the answer I was given: “You have to transform your way of thinking so God can show his truth to you.”

I’m sorry…what?

To be honest, I knew what I was getting myself into before I commented, and I already knew how it would play out. I know that no Christian, no matter how long they’ve been walking with Jesus, has the answers I’m looking for. I’ve accepted that. But I wasn’t looking to bait anybody; my only objective is to plant a tiny seed of humility. I really just want the assurance that I’m not the only “I don’t know” Christian, and that it’s not a sign of weakened faith.

If you’ve been reading this blog long enough, you know that I find safety in the community of skeptics. Any time someone pulls out the “God clearly says” card, I get itchy. I thought the gospel message itself was pretty clear, until I realized in seminary that not all Bible scholars believe the atonement theory. There are some scholars who even believe Jesus’ sacrifice is universal. There are enough dissenters to traditional evangelical talking points that prove these are not just outlier views. Admittedly, the things that seem pretty obvious to me in the Bible are probably sources of confusion for others, so it’s not my tendency to automatically put disagreeing Christians into the heresy box.

About the only thing clear to me in the Bible is the example of servanthood set by Jesus. I could go on about loving your neighbor, serving the poor, and forgiving your enemies, but I’ll sum up Jesus this way for simplicity’s sake: he’s basically everything Donald Trump isn’t. I’ve only had one “The Bible clearly says!!” moment I can think of recently, and that is regarding all this evangelical support for the Trump campaign. I can say with every fiber of conviction within me that a man who espouses racism and misogyny without shame, who strips refugees and immigrants (you know, like Mary and Joseph were) of their personhood, and openly mocks the disabled is nothing like Jesus Christ, and resembles nothing of the behavior he expected of his disciples.

Lately, my conviction ends about there.

Getting back to the parallels of Christian support for slavery and erasure of LGBT rights, I want to share this passage from Noll:

This reminds me of God and the Gay Christian by Matthew Vines. I acquired an advanced copy before it was released, and was surprised by the number of reviews it had already on Amazon and Goodreads. The 1-star reviews were all pretty similar: of course an openly gay man would write a book to justify his lifestyle. Stay away from this book, the author intends to deceive!

I have to admit, a book in favor of the abolitionist movement or of gay rights would be a lot more convincing if written by someone assumed to be against both. It’s the reason that men are encouraged to identify as feminists, because everyone expects women to be in favor of themselves. Sometimes you need voices from “the other team” to get people to really listen.

And yet, who understands the needs, desires, and hopes better than the people being hurt by these viewpoints? This is the underlying reason why the #BlackLivesMatter movement exists. Christians, unfortunately, have a tendency to strive for social change by talking around an issue rather than with those who actually live it.

So, because the social atmosphere of the time believes that X is a sin (interracial marriage, gay marriage, working mothers – take your pick), anyone who disagrees must be coming from an entitled, self-seeking place, hoping to “justify their lifestyle.”

We may not perfectly understand the ways of God, but we understand our fellow humans far less.

I’ve said it before, but I’ll say it again: I firmly believe that half a century from now, the issue of gay rights will be treated the way issues of racial inequality are treated now by the majority of Christians. Churches in the future will say that Christians interpreted the Bible with a cultural bias regarding gay marriage, not through the lens of Truth. I say this not because I want it to happen, but because it’s a time-tested pattern.

If you were an abolitionist Christian in 1865, a significant portion of your society would have condemned you as a heretic, just as they do today in 2016 with regards to gay rights, no matter how much you insist that Jesus Christ is still your Lord and Savior. At the end of the day, I believe that last part is the only thing that really matters. I’m simply not convinced that “correct belief” matters over the condition of the heart.

For all the historical documents we have that provide context into the times, and all the ancient Greek and Hebrew lexicons at our disposal, “Truth” is not always as evident as we claim it to be. That doesn’t mean it’s impossible to to know, but let’s just be realistic about how we engage with it. We all are biased, every one of us.

Like this post? Check out Confessions of a Jew-ish Skeptic, now available on Amazon.

Stay in touch via Facebook and Twitter.

Filed under: Social Issues, Theology Tagged: #BlackLivesMatter, Christian culture, Christianity, Controversy, evangelicals, Facebook, gay marriage, Homosexuality, LGBT, social justice, Spiritual Abuse

July 24, 2016

Moishe Rosen, Jews for Jesus, and interfaith identities

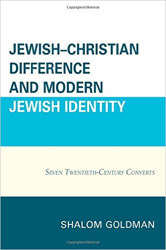

It was with great personal interest that I read Jewish-Christian Difference and Modern Jewish Identity by Shalom Goldman: a collection of mini-biographies about seven 20th-century converts from Judaism to Christianity, and vice versa. Of the seven, only one name was familiar to me besides the biblical Ruth: Moishe Rosen, the controversial founder of Jews for Jesus, the largest messianic Jewish organization in the world.

It was with great personal interest that I read Jewish-Christian Difference and Modern Jewish Identity by Shalom Goldman: a collection of mini-biographies about seven 20th-century converts from Judaism to Christianity, and vice versa. Of the seven, only one name was familiar to me besides the biblical Ruth: Moishe Rosen, the controversial founder of Jews for Jesus, the largest messianic Jewish organization in the world.

Rosen’s story in particular implicitly asks the reader: what makes someone Jewish, or not Jewish? This question becomes more pertinent as an increasing number of American Jews embrace a secular brand of Judaism, allowing them to take part in a cultural narrative and embrace a lineage without partaking in religious tradition, while other Jews embrace Rosen’s “Jew for Jesus” brand.

Reading this book, and the chapter on Rosen in particular, resulted in mixed emotional reactions. Because I was born to Jewish parents, even unobservant ones, that is enough to make me Jewish by most standards. While I never chose to practice the Jewish religion, Judaism nonetheless became the filter through which I saw the world, even as I began to realize that my understanding of God aligned more with Christian theology.

I was born into a tradition that encourages asking questions and welcomes theological debate. It is Judaism – or Jewish culture, perhaps – that I blame for my unrest when I heard in church that God provides for all our needs. My mind immediately shifted to the millions of Jews who perished in the Holocaust: what about their need to be rescued? And, furthermore, what about the needs of people in present day who need food, water, and money with which to pay their bills? It is my Jewish background that is also the source of my discomfort when correct belief is emphasized over action, or what Judaism calls tikkun olam: “mending the world.”

Not surprisingly, I find myself at odds with many of my Christian acquaintances for raising questions and doubts that likely never would have surfaced if I hadn’t said anything. It’s in those moments of unintentionally making others uncomfortable that I almost resent my heritage. After all, I didn’t ask to exist; I didn’t get to choose my place and circumstances of birth. Throughout my young adulthood, I resented being Jewish because of how hard it was to fit in at any church I attended, even though I was just as enamored with the idea of a God Incarnate as everyone else.

It’s taken a long time, but today I accept being Jewish as something about myself that just is. I accept it the same way I accept my curly hair, my right-handedness, my Polish and Russian ancestry. It’s not all I am, but still integral to my identity.

The older I get, the more it becomes clear that religion is as complex as humanity itself, and spiritual identities even more so. I have no issue with checking off the “Christian” box on a Pew Forum, but I have to mark “Ashkenazi Jewish” at the doctor’s office for a complete assessment of my medical history; to be made aware of precautions I must take against certain cancers that people of this gene pool are vulnerable to. I breathed a sigh of relief when I married a gentile, realizing that this greatly decreases our chances of having a child with Tay Sachs, a fatal degenerative disorder that is almost uniquely found among the Ashkenazi faction.

I had hoped to see more of this internal-external dynamic explored in Goldman’s book, which I feel is one of its weaknesses. Goldman’s subjects wrestled with Jewish and Christian theological differences, which are certainly important, but do not show a complete picture. For many converts, conversion is not so much a one-time event, but a daily renewal. We don’t necessarily choose our beliefs, but lineage chooses us, and I wish that Goldman had included chapters about individuals learning to thrive despite constant tension between the two.

Still, anyone interested in religious identity will find this book thought-provoking and worthy of discussion. Read other reviews from the Patheos Book Club.

Like this post? Check out

Confessions of a Prodigal Daughter

,

available on Amazon, or consider

making a donation

to help me continue writing full-time.

Stay in touch via

Facebook

and

Twitter

.

Filed under: Theology Tagged: Christian culture, Christianity, Controversy, Jews for Jesus, Judaism, Messianic Judaism

July 20, 2016

Certainty is the goalpost

“Beware of false teachers” is a biblical warning I’ve heard a lot this election season. “For many are wolves in sheep’s clothing.”

But this is a warning I heard many times before the presidential nominees were chosen. It’s a warning that’s tossed around whenever someone claims to speak for God in a way that defies the norm: “Do not listen to him, he will lead you astray.” People who do this, I’ve been told – those who preach ‘false teachings’ – will be held responsible for all the souls they mislead when they meet God on Judgment Day.

Not surprisingly, I’m more than a little uncomfortable with claiming that my beliefs, my interpretations (based on all the resources at my disposal), my convictions, are all capital-T True. Even if my understanding of ancient Hebrew and Greek was perfect (it’s not), I’m still a human being, tasked with understanding a collection of writings that God himself supposedly dictated.

As far as I’m concerned, if fallible men transcribed the words of a perfect God, and those writings were later copied (and copied and copied and copied) by other fallible men, we’re all looking at Truth through a clouded mirror.

I’m told that the truth is out there to be known; that God himself can be known. But with thousands of Christian denominations in existence, all claiming to possess the truth, who do you trust? How do you trust your own flawed reasoning that this truth is the only Truth, when our hearts are deceitful and God’s ways are “higher than our ways”?

Is gay marriage okay?

Can women preach?

Is hell a literal place?

Was the world actually created in six literal days?

I have no idea.

The limited amount of wisdom I’ve acquired in this journey tells me that agnosticism feels like the only safe stance to take. For me it means I’m not sure if it’s possible to know The Truth (or more than just a sample of it), but I will not stop trying to find it. An alarm sounds off in my head whenever I hear someone say, “The Bible clearly says…” when even a brief look at Christian history says otherwise.

It was my own monopoly on Truth that set me up for the dilemma I face now: not knowing which parts of faith are intentional paradoxes, and which parts are a result of reading my own cultural values into another culture’s values, which were perhaps meant for another people in another place and time.

Again, I have no idea.

I’ve used up many journal pages praying for my faith to return with the same vigor it once had, but what I really miss, if I’m honest, is a feeling: the feeling of certainty. What I should be praying for is more curiosity, more hunger for wisdom. I pray I never lose the verve and passion for reading, studying, and discussing all things theology, all with an expectation of learning new things about God, about people, and being challenged in healthy ways.

As long as that hunger remains, I believe I’m still on track in the direction I wish to go. But if certainty once again becomes the goalpost, I’ll have a list of memorized facts with no real knowledge. What good is that?

Filed under: Theology Tagged: agnosticism, Christian culture, Christianity, evangelicals, prayer

July 15, 2016

When you can’t register shock at the news anymore

Lately I feel guilty about my inability to muster much shock and horror anymore whenever I turn on the news. Many people posted updates last night to say “My heart is breaking” or “I am so horrified,” but I can’t. Maybe it’s because living with depression tints everything with a degree of numbness; maybe because my own cynicism and pessimistic view of the human race makes it easy to believe there will be no end to the creatively brutal ways of killing people.

Whatever the cause, this state of numbness actually makes it easier to keep on taking care of myself in basic ways: getting out of bed, showering, feeding myself. There was a time not too long ago when news of the attack in Nice would have driven me into persistent panic at best, or hiding in a wine bottle at worst…neither of which would enable me to be healthy; to be an agent of change that the world so desperately needs.

Don’t feel bad if you need to turn off the news. Don’t feel like there’s anything wrong with you if you need to censor your newsfeed or avoid certain news outlets to maintain your sanity. Help yourself however you need to so you can help others.

And because it seems needed now more than ever, here’s a sweet sleeping kitty to brighten your day a little.

Filed under: Social Issues, Uncategorized Tagged: depression, grief, self-care, social justice