James Scouller's Blog, page 9

April 18, 2015

The Language of Change (part 1)

Post 3 of 4 in a series of articles on the subject of leading large-scale change in organisations (part 1).

The first post looked at the power and dangers of metaphors in leading change and suggested replacing the “burning platform” with the idea of a “High Noon moment”. The second post discussed the dangers of underestimating how long it takes people to change and what you can do about it. This post – which I’ll spread over four days – will suggest how leaders can frame their change language to best effect.

Change Leaders’ First Problem: Confirmation Bias

When addressing sceptical, cynical or hostile audiences, notably those who doubt the need for change, leaders must avoid the confirmation bias. Why? Because it supports the status quo, blocking change.

The confirmation bias is our sub-conscious habit of searching for information – or interpreting it in a way – that confirms our existing worldview. It means we tend to interpret ambiguous evidence as supporting our existing position. It’s so strong it can lead us to ignore or disparage any data – or its source – that opposes our current outlook and hold fast to our present view.

Why The Confirmation Bias?

Why do we have a confirmation bias? Academics believe it arises from a combination of a desire to cling to a certain belief (motivation) plus faulty thinking (cognitive processing).

The motivational angle: (1) we want to believe whatever feels most desirable or pleasant; (2) we want to believe whatever fits with what we already believed or expected.

The cognitive angle: (1) we can’t focus on more than one thought at a time so it’s hard to test alternative hypotheses in parallel; (2) we use shortcuts, called heuristics, that oversimplify or include errors; (3) our sources of information are too narrow; (4) laziness in reasoning or searching for data.

One academic summed it up like this: “motivation creates the bias, but cognitive factors determine the size of the effect.”

But I think the motivation issue goes deeper. I believe it’s the False Self’s need for control and security in its self-image and worldview – the False Self being your superstructure of limiting beliefs that boxes you in. It wants to feel comfortable in being “right” because that gives it security, even if its conclusions are bleak.

Failings of the Usual Approach To Communication

Whatever its source or mechanism, the confirmation bias is why the usual way of approaching change – (1) define the problem (2) analyse the problem (3) propose a solution – usually runs into trouble.

Research shows this approach doesn’t work. Why? Because without thinking most people look for the data that reinforces their existing view and ignore or disparage the data – sometimes along with its source – that challenges their view. Psychologists learned this through experiments and gave it the label of “confirmation bias”.

So what? The answer is that giving people reasons to change isn’t a good idea if the audience is sceptical, cynical or hostile. If leaders try, all they’ll do is to trigger the confirmation bias and encounter reasons not to change… and therefore resistance… and perhaps sabotage if the leader presses ahead. You see, reasons don’t work at this stage because the audience isn’t really thinking or listening.

What makes things worse is that we know scepticism and cynicism are contagious and can become epidemics, which is why such resistance can become organisation-wide.

A Better Approach

Based on interesting thinking from Stephen Denning in his book, The Secret Language of Leadership, here’s a better approach:

Get your audience’s urgent attention

Stimulate desire for a new future

Then and only then… appeal to the intellect

Why is it better? Because in communicating in this sequence – and the sequence is key – you can get around the confirmation bias, inspire enduring enthusiasm for a vision or cause and spark action towards it.

However, it mustn’t be a one-time thing; you’ve got to stay in a dialogue with colleagues as events unfold … and continue doing so as the story evolves.

Approached this way, the process feels to people as though they are engaged in a big conversation that opens up new possibilities and horizons. It’s not as though the “great leader” is talking down to them with an “I’m in charge, I know best and I have all the answers” mentality. Instead the leader is with them, conversing; she’s one of them, not apart.

Which Step Is The Most Important?

Of the three, the middle step – stimulating desire – is the most important one. Without that there’s no point in getting their attention in the first place (step 1) and you won’t get to step 3 because there’s no motivating aim to reinforce with reasoning about the how, why and when.

We’ll examine the three steps in more detail (and I’ll give action tips on each) in the next three posts, which will appear in the next three days.

The author is James Scouller, an executive coach. His book, The Three Levels of Leadership: How to Develop Your Leadership Presence, Knowhow and Skill, was published in May 2011. You can learn more about it at www.three-levels-of-leadership.com. If you want to see its reviews, click here: leadership book reviews. If you want to know where to buy it, click HERE. You can read more about his executive coaching services at The Scouller Partnership’s website.

February 15, 2015

Why Do Organisational Change Initiatives Overrun?

Post 2 of 4 in a series of articles on the subject of leading large-scale change in organisations.

The first post looked at the power and dangers of metaphors in leading change and suggested replacing the “burning platform” with the idea of a “High Noon moment”. This post looks at the dangers of underestimating how long it takes people to change and what you can do about it.

Change Initiative Overruns

In my experience, most change initiatives take longer – sometimes much longer – than leaders anticipated. The data backs this up. For example:

The Standish Group reported in 2004 that 71% of IT change projects overran their target timelines.

A 2012 report by the Saïd Business School at the University of Oxford showed that the typical project took on average 24% longer than expected. Note it said the “typical project”. Only 31% of the projects they studied were “typical”, meaning there’s a strong possibility that your next change project will overrun by much more than 24%.

So why is this?

Why Organisational Change Initiatives Overrun

Consultants have offered explanations like:

“There wasn’t enough dissatisfaction with the status quo – leaders hadn’t created a “burning platform”. Or instead the end state – the vision or goal – wasn’t compelling enough. Either way, people lacked motivation to change.”

“Leaders didn’t pay enough attention to project planning at the beginning. In particular, they didn’t test their starting assumptions, which later proved to be false.”

“Stakeholders outside the target change audience – e.g. shareholders, people higher in the hierarchy, politicians or whoever – weren’t fully behind the initiative’s aims and approach before it started.”

“Leaders allowed ‘mission creep’ to blur the boundaries of their project, causing loss of focus.”

“The projects didn’t make use of the best scheduling and planning tools.”

“Leaders didn’t track progress and adjust their plans as events unfolded.”

Now I’m not arguing with these insights, but I feel they omit the most important point of all: we don’t truly “get it” that change takes time, which often causes us to be ridiculously optimistic when setting timescales.

Why do I say this? Well, consider this question: what must happen if any organisational change is to succeed?

What Has To Happen?

The answer, simply put, is that people must collectively change their attitudes and start behaving differently.

Now hold that thought in mind as I bring in two perspectives from research that many change leaders overlook.

Outer Change Depends on Inner Transition

William Bridges, in his books, Transitions and Managing Transitions, described the three psychological phases that we all go through before we can accept a change: (1) Endings (2) the Neutral Zone (3) New Beginning.

In Endings , we struggle with losing something – or being about to lose something – we’ve become familiar and safe with. This could be our job through redundancy … or the way we used to do a job… or our spouse through death. In this phase you will often see denial, shock or anger. The significance of Endings is this: people have to accept that something is ending before they’ll begin to take the new idea on board.

In Neutral , we’re in an uncomfortable no-man’s-land where we know the old order has gone, but we haven’t accepted the new world. Feelings like frustration with new ways of working, confusion, uncertainty about our identity or self-worth, ambivalence and scepticism often reign.

In New Beginning , scepticism gives way to acceptance, openness to learning, hope, enthusiasm and renewed commitment to our group and role. Now we start behaving in ways that adapt to and support the outer change.

The big point is this: it takes time for all of us to move through these stages when we’re faced with change. This is a psychological fundamental that no leader can avoid.

“Okay, but so what,” you may be thinking?

Well, consider that leaders are usually further along this transition process than others in their organisation because they’ve been pondering on the change for longer. They often forget that it took them months or years to pass through the three phases and assume their colleagues should “get it” instantly – or within days of learning about the change idea.

Thus, they often underestimate the time needed to make the change happen. So guess what? The initiative overruns, but it’s not down to technical skill or a lack of “walking the talk”. It’s because they ignored a psychological reality.

Worse, they can assume that people in the “Ending” or “Neutral” zones are being uncooperative or resistant. This can cause leaders to make damaging decisions like firing people they need or ignoring intelligent objections. The point is this: if your change initiative doesn’t allow for the inevitable time delay in transitioning across the three stages, YOU could become the problem if you get irritated, behave foolishly and make rash decisions… and end up sabotaging the very change you wanted.

People Transition at Different Speeds

There’s a second factor that can magnify the first.

You see, not only do we all go through Bridges’ three phases, we move through them at different rates.

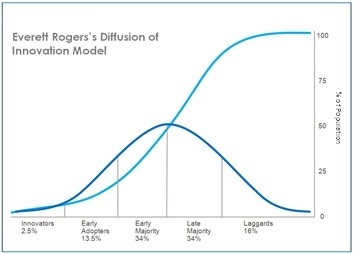

The first person to research this insight was Everett Rogers, who published his findings in his classic book, Diffusion of Innovations. He found that we can classify people’s attitude to innovation or change into five categories: (1) Innovators (2) Early Adopters (3) Early Majority (4) Late Majority (5) Laggards. He summarised his model in this diagram:

Rogers found that Innovators and Early Adopters – roughly 16% of the population – can move through the adoption cycle ten times faster than Laggards and about four times faster than the Majority (68% of the total).

In other words, not only do you have to accept the reality of the three-phase transition, you have to wait for most people to catch up with the change idea because less than 20% will respond quickly.

Admittedly, you can probably speed the adoption process by:

Making the change idea feel more attractive or more urgent.

Ensuring that the way you describe the change fits people’s values or sense of identity or habits or previous experiences.

Making it easier and more convenient to adopt (perhaps through training or providing the right tools).

Offering people a way to try out the change with minimal risk.

Ensuring that leaders are “walking the talk” and showing how important the change is.

Demonstrating early evidence – perhaps through quick wins – that the change is working.

But again, the fact is that people do vary in their attitudes to change, so if you adopt a one-size-fits-all attitude and believe everyone will grasp and accept the change instantly, you’ll be disappointed. Bottom line: your change initiative will take far longer than you expected.

“But We Don’t Have Time…”

Have you ever found yourself in high-pressure change situations where bosses have said something like, “But we don’t have time – it’s got to happen in XYZ timescale”?

I certainly have. And it can cause us to make unrealistic promises about how quickly the change will happen. But in my experience, it’s never true that we “don’t have time”. Unless the company is about to go bust or run out of cash, there is time. What they really mean is, their ego can’t wait. The trouble is, their ego is no match for psychological reality.

What Does This Mean?

I realise it isn’t easy to tell an egotistical boss that what they’re asking for is unrealistic. But it often is, and in my experience it’s better to tell them up front than have them find out six months or a year later.

The message is simple: you probably need to stretch your change timescale and plan accordingly, while making sure your stakeholders understand how long change takes. That way, no one’s disappointed and, more important, your frustration won’t spill over into irritation and foolish decisions.

Better to face the facts and plan accordingly, I suggest.

The author is James Scouller, an executive coach. His book, The Three Levels of Leadership: How to Develop Your Leadership Presence, Knowhow and Skill, was published in May 2011. You can learn more about it at www.three-levels-of-leadership.com. If you want to see its reviews, click here: leadership book reviews. If you want to know where to buy it, click HERE. You can read more about his executive coaching services at The Scouller Partnership’s website.

December 4, 2014

Are We Serious About Growing Leaders?

In industry, do we take the challenge of growing future leaders seriously? I don’t think we do and here’s why…

Let me first explain why the question has arisen.

Reactions to The Three Levels of Leadership

My book, The Three Levels of Leadership, came out in 2011. Since then, many readers have asked me to create a training programme based on it. Or instead, to offer train-the-trainer certification for those wanting to offer a “three levels of leadership”-based course for leaders.

My firm answer until the start of 2014 was always “no.” Why? Because I was suspicious of the leadership development programmes I’ve come across down the decades. I always felt they made little difference to those attending them – I couldn’t see any change or growth in their attitude and behaviour. Being an executive coach, I favoured coaching over formal training for growing leaders, but then I would, wouldn’t I?

What’s Wrong With Leadership Programmes?

But as the number of requests to offer a “Three Levels”-based programme increased, I began to wonder if I was guilty of prejudice against training courses.

Why couldn’t we, I wondered, create a 21st century programme for leaders combining experience-based learning, formal classroom teaching, executive coaching, self-reflection, feedback and on-the-job challenges? That led me to explore what others felt about the success of leadership development programmes. Guess what? I found I wasn’t alone in my views. Distilling it all down and blending it with my own experience, the criticisms boil down to three themes:

Poor selection of candidates for training. For example, by mistaking hubris-based confidence for genuine potential.

Programme design . Comments I’ve heard, read or made myself include:

“It’s too classroom-based.”

“It’s not experiential enough.”

“It’s too often a one-time sheep dip; it needs to be phased over a longer period with between-module practical assignments.”

“There’s not enough time for reflection.”

“Leaders aren’t given help in working on their mindsets and presuppositions so they remain locked into their old habits.”

“There’s too much teaching and too little on-the-job mentoring and coaching.”

“It’s not tied in enough to the specific challenges we’re facing in our business.”

“The subject of group dynamics is too often ignored.”

Unhelpful company cultures that make it harder for budding leaders to grow. For example, by being too quick to punish mistakes and risk-taking. Or having too few senior executives who believe it’s a priority to grow future leaders.

Creating a 21st Century Programme for Leaders

So I set to work designing a learning experience that addresses these three concerns – or at least the first two. A programme that focuses not just on knowhow and skills, but on developing a leader’s “presence” through self-mastery (that is, mastery of one’s mind, behavioural reactions under pressure and attitude towards others).

Eventually I arrived at a first draft. I envisaged a 14-module programme, spaced out over a year or perhaps 18 months, needing 34 days of face-to-face learning plus homework back on the job.

Reaction

When I mentioned this first draft to friends in the corporate sector they asked, “How long will the programme last?” “34 days,” I replied. “What,” they shouted, “you’ve got to be joking!”

But I wasn’t.

And that brings me back to the question at the start of this blog article. Are we serious about growing our leaders? My friends’ reactions suggest we’re not. But why should the idea of a 34-day programme for leaders blow people’s minds?

Comparisons

Think about it, how long does it take to train a fully qualified accountant? Or a marketing professional? Or a lawyer? Or a doctor? A lot more than 34 days, but we regard their training as normal. But is acquiring the skill to consistently connect with and influence people (and stay resilient in tough times) any less difficult? Just as important, leaders have an enormous effect on the world for good or ill, so why do we have a different attitude to their development?

Consider the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst where the British Army trains its new officers. Their programme lasts 44 weeks. 44 weeks! That’s 5 weeks of physical conditioning and 39 weeks of practical leader training before officer cadets take up their first assignment as a 2nd Lieutenant. And then they have further leadership training at Staff College as they rise further in the ranks.

Who do you know in the corporate sector that’s spent 44 days learning how to lead, never mind 44 weeks, on top of all their technical education and on-the-job experience? I’ll bet your answer is, “No one.” In fact, in my experience, few senior executives have had more than 4-6 days training or development as a leader. No wonder surveys tell us how little faith we have in our business leaders. And no wonder so few people feel engaged in their work. [* See footnote]

To be fair to those friends I spoke to, when I pointed out these comparisons they looked thoughtful and said, “You’ve got a point there.”

Persisting

I wasn’t suggesting anything as long as the Sandhurst programme. But I was proposing something that takes the growth of business leaders seriously. I’m going to continue working on this idea of a 21st-century programme for leaders to help them work on their psychology and grow their self-mastery and leadership presence, not just their knowhow and skills. But meanwhile I believe it’s time we asked ourselves:

Are we serious about growing leaders in industry ?

How much time and money are we prepared to spend in growing leaders of the future?

Why wouldn’t we invest as much effort in growing leaders as we would in, say, equipping accountants with enough technical skill and knowhow? After all, our future could depend on it.

* The 2013 Edelmann Trust Barometer’s survey of 26,000 people across 26 countries found that only 20% believe business leaders can correct the big issues facing their industries. In other words, 80% think their leaders aren’t up to the job. And Gallup’s State of the Global Workplace 2012 survey reported that only 13% of employees across 142 countries feel engaged in their work and connected to their company. It also found that 24% (nearly twice as many) feel negative and act out their hostility, undermining the work of the engaged minority. The 63% majority? They don’t much care.

The author is James Scouller, an executive coach. His book, The Three Levels of Leadership: How to Develop Your Leadership Presence, Knowhow and Skill, was published in May 2011. You can learn more about it at www.three-levels-of-leadership.com. If you want to see its reviews, click here: leadership book reviews. If you want to know where to buy it, click HERE. You can read more about his executive coaching services at The Scouller Partnership’s website.

November 4, 2014

Are We Serious About Growing Leaders?

In industry, do we take the challenge of growing future leaders seriously? I don’t think we do and here’s why…

Let me first explain why the question has arisen.

Reactions to The Three Levels of Leadership

My book, The Three Levels of Leadership, came out in 2011. Since then, many readers have asked me to create a training programme based on it. Or instead, to offer train-the-trainer certification for those wanting to offer a “three levels of leadership”-based course for leaders.

My firm answer until the start of 2014 was always “no.” Why? Because I was suspicious of the leadership development programmes I’ve come across down the decades. I always felt they made little difference to those attending them – I couldn’t see any change or growth in their attitude and behaviour.

What’s Wrong With Leadership Programmes?

But as the number of requests to offer a “Three Levels”-based programme increased, I began to wonder if I was guilty of prejudice against training courses. Why couldn’t we, I wondered, create a 21st century programme for leaders combining experience-based learning, formal training, executive coaching, self-reflection and feedback? That led me to explore what others felt about the success of leadership development programmes. Guess what? I found I wasn’t alone in my views. Distilling it all down and blending it with my own experience, the criticisms boil down to three themes:

Poor selection of candidates for training. For example, by mistaking hubris-based confidence for genuine potential.

Programme design . Comments I’ve heard, read or made myself include:

“It’s too classroom-based.”

“It’s not experiential enough.”

“It’s too often a one-time sheep dip; it needs to be phased over a longer period with between-module practical assignments.”

“There’s not enough time for reflection.”

“Leaders aren’t given help in working on their mindsets and presuppositions so they remain locked into their old habits.”

“There’s too much teaching and too little on-the-job mentoring and coaching.”

“It’s not tied in enough to the specific challenges we’re facing in our business.”

“The subject of group dynamics is too often ignored.”

Unhelpful company cultures that make it harder for budding leaders to grow. For example, by being too quick to punish mistakes and risk-taking. Or having too few senior executives who believe it’s a priority to grow future leaders.

Creating a 21st Century Programme for Leaders

So I set to work designing a learning experience that addresses these three concerns – or at least the first two. A programme that focuses not just on knowhow and skills, but on developing a leader’s “presence” through self-mastery (that is, mastery of one’s mind). Eventually I arrived at a first draft. I envisaged a 14-module programme, spaced out over a year or perhaps 18 months, needing 34 days of face-to-face learning plus homework back on the job.

Reaction

When I mentioned this first draft to friends in the corporate sector they asked, “How long will the programme last?” “34 days,” I replied. “What,” they shouted, “you’ve got to be joking!”

But I wasn’t.

And that brings me back to the question at the start of this blog article. Are we serious about growing our leaders? My friends’ reactions suggest we’re not. But why should the idea of a 34-day programme for leaders blow people’s minds?

Comparisons

Think about it, how long does it take to train a fully qualified accountant? Or a marketing professional? Or a lawyer? Or a doctor? A lot more than 34 days, but we regard their training as normal. And yet leaders have an enormous effect on the world for good or ill so why do we have a different attitude to their development?

Consider the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst where the British Army trains its new officers. Their programme lasts 44 weeks. 44 weeks! That’s 5 week of physical conditioning and 39 weeks of practical leader training before officer cadets take up their first assignment as a 2nd Lieutenant. And then they have further leadership training at Staff College as they rise further in the ranks.

Who do you know in the corporate sector that’s spent 44 days learning how to lead, never mind 44 weeks? I’ll bet your answer is, “No one.” In fact, in my experience, few senior executives have had more than 4-6 days training or development as a leader. No wonder surveys tell us how little faith we have in our business leaders. And no wonder so few people feel engaged in their work.*

To be fair to those friends I spoke to, when I pointed out these comparisons they looked thoughtful and said, “You’ve got a point there.”

Persisting

I wasn’t suggesting anything like the Sandhurst programme. But I was proposing something that takes the growth of business leaders seriously. I’m going to continue working on this idea of a 21st-century programme for leaders that helps them work on their psychology and grow their self-mastery, not just their knowhow and skills. But I believe it’s time we asked ourselves:

Are we serious about growing leaders in industry ?

How much time and money are we prepared to spend in growing leaders of the future?

Why wouldn’t we invest as much effort in growing leaders as we would in, say, equipping accountants with enough technical skill and knowhow? After all, our future could depend on it.

* The 2013 Edelmann Trust Barometer’s survey of 26,000 people across 26 countries found that only 20% believe business leaders can correct the big issues facing their industries. In other words, 80% think their leaders aren’t up to the job. And Gallup’s State of the Global Workplace 2012 survey reported that only 13% of employees across 142 countries feel engaged in their work and connected to their company. It also found that 24% (nearly twice as many) feel negative and act out their hostility, undermining the work of the engaged minority. The 63% majority? They don’t much care.

The author is James Scouller, an executive coach. His book, The Three Levels of Leadership: How to Develop Your Leadership Presence, Knowhow and Skill, was published in May 2011. You can learn more about it at www.three-levels-of-leadership.com. If you want to see its reviews, click here: leadership book reviews. If you want to know where to buy it, click HERE. You can read more about his executive coaching services at The Scouller Partnership’s website.

October 27, 2014

Do We Always Need Leadership?

Does a group or a firm always need leadership? The surprising answer is no and this short article explains why.

Let’s start with first principles: what do we mean by leadership?

Well, I define it as a process. To be more exact, the process of paying attention to four dimensions simultaneously: (1) Motivating Purpose (2) Task, Progress & Results (3) Group Unity and (4) Attention to Individuals.

Now it’s the first dimension, Motivating Purpose, that most concerns us here. You see, Motivating Purpose is the first building block of leadership because leadership can’t exist without a sense of shared destination. I say that because leadership, by definition, means leading and being led somewhere, which always involves direction and a destination (an objective or endgame or vision). Following this line of logic, leadership without a clear, commonly held, motivating purpose isn’t leadership.

So if heading up a group or a firm without a real motivating purpose isn’t leadership, what is it? My word for it is stewardship.

Stewardship is the art of making the best of current conditions, of solving immediate problems, of good administration. Able stewards cut costs, improve efficiency and solve problems, but they don’t move people or the group forward. To be clear, I’m not criticising people who act as stewards rather than leaders as their role is valid. I’m merely pointing out that what they’re offering isn’t leadership. For if the group or company is going nowhere, if there’s no shared motivating purpose, no sense of destination; leadership is absent.

With this in mind, the point I’m coming to is this: if (1) the situation doesn’t demand innovation or change in people’s attitudes or behaviour and (2), the shareholders, directors, customers and employees are happy with a “more of the same” stewardship approach, then leadership isn’t essential. Stewardship will do. It’s as simple as that.

Now you might be wondering: what groups or organisations (and their stakeholders) wouldn’t demand innovation or change? Well, consider the board of trustees of a small charity. They may feel that a “steady as you go” approach is enough; that all they need to do is keep an eye on the organisation’s efficiency and ethics.

The only trouble is, stewardship in a business context will usually see a firm gradually fossilise and when it does it’ll be outmanoeuvred by competitors. Or instead, if the firm carries on as before and customer behaviour changes (as it always does in time) it will eventually be caught out. But in the short term, stewardship may be all that’s needed.

Please don’t misunderstand me, I’m not recommending stewardship over leadership; just pointing out that not everyone wants, welcomes or needs leadership all the time.

The author is James Scouller, an executive coach. His book, The Three Levels of Leadership: How to Develop Your Leadership Presence, Knowhow and Skill, was published in May 2011. You can learn more about it at www.three-levels-of-leadership.com. If you want to see its reviews, click here: leadership book reviews. If you want to know where to buy it, click HERE. You can read more about his executive coaching services at The Scouller Partnership’s website.

September 11, 2014

From “Burning Platform” to “High Noon”

Post 1 of 4 in a series of articles on the subject of leading major large-scale change in organisations.

We start by considering the power and dangers of metaphors in leading change. Metaphors help in connecting with and influencing others because they distil the message in a vivid memorable way. But they can backfire. Let’s consider the example of the “burning platform”.

Origin of the “Burning Platform” Metaphor

Daryl Conner, an organisational change consultant, first used the “burning platform” metaphor in the late 1980s. It stemmed from the terrible 1988 Piper Alpha incident in which a drilling platform off the coast of Scotland exploded and became engulfed in fire, killing 167 people. Only 63 crew members survived. One jumped 15 stories from the platform into the water below to save his life. He commented afterwards, “It was either jump or fry. So I jumped.”

My First Encounter

I didn’t come across the “burning platform” metaphor until seven years later, in 1995, when reading a Harvard Business Review interview with Larry Bossidy, then CEO of AlliedSignal. When asked about the challenge of achieving change in a large organisation, he explained:

“I believe in the “burning platform” theory of change. When the roustabouts [oil rig workers] are standing on the offshore oil rig and the foreman yells, ‘Jump into the water,’ not only won’t they jump but they also won’t feel too kindly towards the foreman. There may be sharks in the water. They’ll jump only when they themselves see the flames shooting up from the platform… The leader’s job is to help everyone see the platform is burning, whether the flames are apparent or not. The process of change begins when people decide to take the flames seriously…”

Reading his words helped at the time because I was in my first role as a CEO. They made me realise I couldn’t lead change in an old-fashioned business that was in danger of sinking beneath the waves unless my colleagues were similarly uneasy about our trajectory. But it turns out the “burning platform” metaphor, although powerful, has caused misunderstanding, anger, criticism and resistance in some parts.

Misunderstandings

Daryl Conner intended the “burning platform” to be a metaphor for intense commitment; the resolve, the iron will to break the status quo and do something different from the past, something probably difficult or risky… and keep going. The idea was inspired by the man, Andy Machon, who, faced with the toughest of choices, saved his life by jumping from the oil rig.

Unfortunately, metaphors are so powerful that, once launched, they’re no longer controlled by their creators. And being vivid they can take on unintended meanings. With the “burning platform,” the imagery is so potent it can misdirect people’s attention.

Conner commented on this in a 2012 blog article. He’d realised that many people were focusing on the danger and fear evoked by the “burning platform” idea, not the sense of resolve and iron will he’d intended. This misunderstanding has led some executives to believe that:

People will only commit to large-scale change when they’re terrified of impending organisational disaster.

It’s a good idea for leaders to manipulate their colleagues – by lying, exaggerating or withholding data – into believing that urgent changes are needed even if they’re not.

Anger, Criticism & Resistance to the Idea

Misunderstandings aren’t the only problem. Some senior executives and consultants become critical, angry or resistant when discussing “the burning platform”.

There are those, for example, who believe the “burning platform” idea gives leaders the green light to compel people to do something they otherwise wouldn’t do. This angers them and they respond with statements like, “Real leaders don’t refer to a ‘burning platform’ when leading change” or “People won’t change by wanting to avoid an outcome; they change when they’re working towards something positive.”

Others with cooler heads don’t get so annoyed. Instead they point to the findings of neuroscience. They claim that when presented with a crisis of the kind depicted by the burning platform we activate the brain’s limbic system, which is associated with intense fear and the fight – flight – freeze response. They argue that this high level of anxiety and stress means we’ll think less clearly and therefore change will stall. Thus, they argue, the “burning platform” metaphor is counter-productive.

The critics say that if leaders want change they should rely not on fear, but appeal to reason and explain (1) the current circumstances (2) what must change and why and (3) why everyone will gain. But I believe they have failed to connect with Conner’s original intent and missed the deeper part of his message.

The Message Behind the Metaphor

That’s a shame because Conner was only searching for a vivid linguistic device to illustrate his message.

The message being that we need an unshakeable resolve, an ironclad commitment, to dare to act and follow through if major, large-scale change is to happen. The deeper message is that for such resolve to emerge, two conditions must be true:

First, that we’re dissatisfied with our present position or current trajectory.

Second, that we strongly prefer the newly defined goal or destination (vision).

The twin feelings of dissatisfaction (with the present state or anticipated result of following the same course) and desire (for the new future) are crucial. We need both. But in my experience – and according to 80 years of research by experts like Daryl Conner, Kurt Lewin, John Kotter and James Belasco – an intense commitment to change only emerges after initial dissatisfaction with the status quo. I’ll explore why that is in the second instalment of the series.

For now, all I want to say is that I’ve seen chief executives attempt to impose a new vision on colleagues who were happy with the way things were. Thus, their people asked themselves, “What’s wrong with where we’re heading, we’re doing fine as we are.” And guess what? They subtly undermined or even sabotaged the change initiatives, which fizzled out. The CEOs ignored the dissatisfaction side of the equation. They mistakenly thought the vision and perhaps their high rank would be enough to stimulate change.

So dissatisfaction with the status quo and desire for the new future are like two sides of the same coin: they are the twin forerunners of change. You could say they are the Yin and Yang of change – not polar opposites, but rather complementary forces that together drive sustainable change. But one (dissatisfaction) comes before the other.

A New Metaphor for Change

Can we find a new metaphor that captures Daryl Conner’s original intent while avoiding the unhelpful misunderstandings, criticism and resistance we’ve just discussed? I think we can.

The new metaphor I’m suggesting is “High Noon”.

Why “High Noon”?

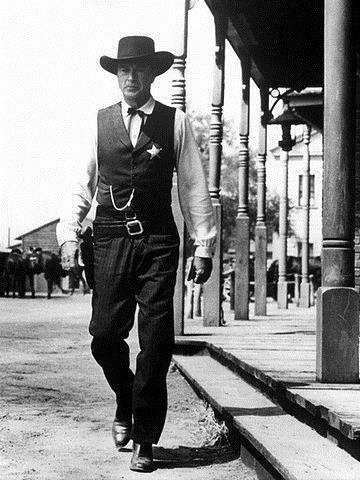

High Noon is a 1952 American Western starring Gary Cooper. He played a newly-married sheriff who’d decided to give up his badge to become a shopkeeper in another town. This was his last day in the job; he was planning to leave with his new wife on the noon train. Then he learns that a killer he’d brought to justice is out of jail and due to return on that same noon train, having vowed to kill him. To make matters worse, three of his gunslinger friends are meeting the killer at the station, leaving the sheriff up against four men.

High Noon – A Metaphor for Resolve

The townspeople are so scared of the killer and his gang that they won’t help the sheriff. And his new wife – a Quaker and pacifist – won’t let him stay and fight; she tells him she’s leaving on the noon train with or without him. What’s he going to do?

He could do nothing, ignore the problem and board the train with his wife before the four killers realise he’s gone. That way he avoids danger and pleases his new wife. The trouble is, he thinks the gang will hunt him down and, before they do, wreak revenge on the townsfolk.

In the end he makes an irrevocable choice and stays to fight the gang of four. And of course he wins. But – and this is crucial – he only does so with his wife’s help as she changes her mind, puts aside her religious beliefs, leaves the train, comes to his aid, kills one of the four and distracts another, enabling the sheriff to shoot him.

High Noon as a change metaphor represents resolve, steadfastness, the need to make an intense commitment to a new direction despite pressure to stay with the old course.

It recognises that for change to happen (abandoning the plan to leave and become a shopkeeper, risking the love of a new wife) we must feel both the unacceptability of the status quo (being pursued by the killers, letting them hunt down other townspeople) and the desirability of a better alternative (staying and confronting the gang, ending the problem, feeling he’s done the right thing and been true to himself).

Of course, some might see High Noon as a monument to an individual “lone wolf” attitude. But in fact the sheriff wasn’t alone in facing a High Noon moment. His wife was facing it too. In the end she decided to change, to let go of long-held principles and come to his aid. So it’s a story of collective High Noon. We must all feel we’re at a point of no return, we must all feel we have little choice but commit to cross the Rubicon. Although the intense commitment to change often starts in just one person or a small group, it must spread to a critical mass of people if it’s to succeed.

Every successful big change initiative must face its High Noon moment. Yes, the High Noon metaphor involves fear – it shares this with the burning platform – but the metaphor, the image itself, is not so fear-inducing. We switch from a picture of a terrifying inferno to a man walking resolutely toward his destiny, doing what he thinks is right despite the risks, knowing the alternative is intolerable to him.

No metaphor is perfect – the reactions to the “burning platform” prove that. But “High Noon” may have the advantage of capturing the intense resolve to follow a new, difficult course of action with less risk of misinterpretation.

The Bottom Line

If you’re to lead major change successfully, you must create the conditions for your colleagues to experience a personal and collective “High Noon” moment. That’s when the unacceptability of the status quo and the preference for the new future crystallise into intense resolve. A resolve that overcomes all obstacles.

In the next instalment we’ll look at why appeals to reason and the logic behind the change idea aren’t usually enough to get people behind significant changes in direction.

The author is James Scouller, an executive coach. His book, The Three Levels of Leadership: How to Develop Your Leadership Presence, Knowhow and Skill, was published in May 2011. You can learn more about it at www.three-levels-of-leadership.com. If you want to see its reviews, click here: leadership book reviews. If you want to know where to buy it, click HERE. You can read more about his executive coaching services at The Scouller Partnership’s website.

September 5, 2014

From “Burning Platform” to “High Noon”

Post 1 of 4 in a series of articles on the subject of leading major large-scale change in organisations.

We start by considering the power and dangers of metaphors in leading change. Metaphors help in connecting with and influencing others because they distil the message in a vivid memorable way. But they can backfire. Let’s consider the example of the “burning platform”.

Origin of the “Burning Platform” Metaphor

Daryl Conner, an organisational change consultant, first used the “burning platform” metaphor in the late 1980s. It stemmed from the terrible 1988 Piper Alpha incident in which a drilling platform off the coast of Scotland exploded and became engulfed in fire, killing 167 people. Only 63 crew members survived. One jumped 15 stories from the platform into the water below to save his life. He commented afterwards, “It was either jump or fry. So I jumped.”

My First Encounter

I didn’t come across the “burning platform” metaphor until seven years later, in 1995, when reading a Harvard Business Review interview with Larry Bossidy, then CEO of AlliedSignal. When asked about the challenge of achieving change in a large organisation, he explained:

“I believe in the “burning platform” theory of change. When the roustabouts [oil rig workers] are standing on the offshore oil rig and the foreman yells, ‘Jump into the water,’ not only won’t they jump but they also won’t feel too kindly towards the foreman. There may be sharks in the water. They’ll jump only when they themselves see the flames shooting up from the platform… The leader’s job is to help everyone see the platform is burning, whether the flames are apparent or not. The process of change begins when people decide to take the flames seriously…”

Reading his words helped at the time because I was in my first role as a CEO. They made me realise that I couldn’t lead change in an old-fashioned business that was in danger of sinking beneath the waves unless my colleagues were similarly uneasy about our trajectory. But it turns out the “burning platform” metaphor, although powerful, has caused misunderstanding, anger, criticism and resistance in some parts.

Misunderstandings

Daryl Conner intended the “burning platform” to be a metaphor for intense commitment; the resolve, the iron will to break the status quo and do something different from the past, something probably difficult or risky… and keep going. The idea was inspired by the man, Andy Machon, who, faced with the toughest of choices, saved his life by jumping from the oil rig.

Unfortunately, metaphors are so powerful that, once launched, they’re no longer controlled by their creators. And being vivid they can take on unintended meanings. With the “burning platform,” the imagery is so potent it can misdirect people’s attention.

Conner commented on this point in a 2012 blog article. He’d realised that many people were focusing on the danger and fear evoked by the “burning platform” idea, not the sense of resolve and iron will he’d intended. This misunderstanding has led some executives to believe that:

People will only commit to large-scale change when they’re terrified of impending organisational disaster.

It’s a good idea for leaders to manipulate their colleagues – by lying, exaggerating or withholding data – into believing that urgent changes are needed even if they’re not.

Anger, Criticism & Resistance to the Idea

Misunderstandings aren’t the only problem. Some senior executives and consultants become critical, angry or resistant when discussing “the burning platform”.

There are those, for example, who believe the “burning platform” idea gives leaders the green light to compel people to do something they otherwise wouldn’t do. This angers them and they respond with statements like, “Real leaders don’t refer to a ‘burning platform’ when leading change” or “People won’t change by wanting to avoid an outcome; they change when they’re working towards something positive.”

Others with cooler heads don’t get so annoyed. Instead they point to the findings of neuroscience. They claim that when presented with a crisis of the kind depicted by the burning platform we activate the brain’s limbic system, which is associated with intense fear and the fight – flight – freeze response. They argue that this high level of anxiety and stress means we’ll think less clearly and therefore change will stall. Thus, they argue, the “burning platform” metaphor is counter-productive.

The critics say that if leaders want change they should rely not on fear, but appeal to reason and explain (1) the current circumstances (2) what must change and why and (3) why everyone will gain. But I believe they have failed to connect with Conner’s original intent and missed the deeper part of his message.

The Message Behind the Metaphor

That’s a shame because Conner was only searching for a vivid linguistic device to illustrate his message.

The message being that we need an unshakeable resolve, an ironclad commitment, to dare to act and follow through if major, large-scale change is to happen. The deeper message is that for such resolve to emerge, two conditions must be true:

First, that we’re dissatisfied with our present position or current trajectory.

Second, that we strongly prefer the newly defined goal or destination (vision).

The twin feelings of dissatisfaction (with the present state or anticipated result of following the same course) and desire (for the new future) are crucial. We need both. But in my experience – and according to 80 years of research by experts like Daryl Conner, Kurt Lewin, John Kotter and James Belasco – an intense commitment to change only emerges after initial dissatisfaction with the status quo. I’ll explore why that is in the second instalment of the series.

For now, all I want to say is that I’ve seen chief executives attempt to impose a new vision on colleagues who were happy with the way things were. Thus, their people asked themselves, “What’s wrong with where we’re heading, we’re doing fine as we are.” And guess what? They subtly undermined or even sabotaged the change initiatives, which fizzled out. The CEOs ignored the dissatisfaction side of the equation. They mistakenly thought the vision and perhaps their high rank would be enough to stimulate change.

So dissatisfaction with the status quo and desire for the new future are like two sides of the same coin: they are the twin forerunners of change. You could say they are the Yin and Yang of change – not polar opposites, but rather complementary forces that together drive sustainable change. But one (dissatisfaction) comes before the other.

A New Metaphor for Change

Can we find a new metaphor that captures Daryl Conner’s original intent while avoiding the unhelpful misunderstandings, criticism and resistance we’ve just discussed? I think we can.

The new metaphor I’m suggesting is “High Noon”.

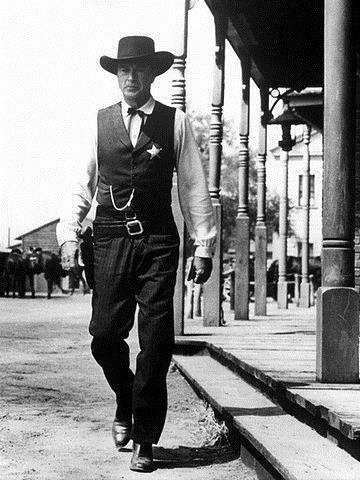

Why “High Noon”?

High Noon is a 1952 American Western starring Gary Cooper. He played a newly-married sheriff who’d decided to give up his badge to become a shopkeeper in another town. This was his last day in the job; he was planning to leave with his new wife on the noon train. Then he learns that a killer he’d brought to justice is out of jail and due to return on that same noon train, having vowed to kill him. To make matters worse, three of his gunslinger friends are meeting the killer at the station, leaving the sheriff up against four men.

The townspeople are so scared of the killer and his gang that they won’t help the sheriff. And his new wife – a Quaker and pacifist – won’t let him stay and fight; she tells him she’s leaving on the noon train with or without him. What’s he going to do?

High Noon: A Metaphor for Resolve

He could do nothing, ignore the problem and board the train with his wife before the four killers realise he’s gone. That way he avoids danger and pleases his new wife. The trouble is, he thinks the gang will hunt him down and, before they do, wreak revenge on the townsfolk.

In the end he makes an irrevocable choice and stays to fight the gang of four. And of course he wins. But – and this is crucial – he only does so with his wife’s help as she changes her mind, puts aside her religious beliefs, leaves the train, comes to his aid, kills one of the four and distracts another, enabling the sheriff to shoot him.

High Noon as a change metaphor represents resolve, steadfastness, the need to make an intense commitment to a new direction despite pressure to stay with the old course.

It recognises that for change to happen (abandoning the plan to leave and become a shopkeeper, risking the love of a new wife) we must feel both the unacceptability of the status quo (being pursued by the killers, letting them hunt down other townspeople) and the desirability of a better alternative (staying and confronting the gang, ending the problem, feeling he’s done the right thing and been true to himself).

Of course, some might see High Noon as a monument to an individual “lone wolf” attitude. But in fact the sheriff wasn’t alone in facing a High Noon moment. His wife was facing it too. In the end she decided to change, to let go of long-held principles and come to his aid. So it’s a story of collective High Noon. We must all feel we’re at a point of no return, we must all feel we have little choice but commit to cross the Rubicon. Although the intense commitment to change often starts in just one person or a small group, it must spread to a critical mass of people if it’s to succeed.

Every successful big change initiative must face its High Noon moment. Yes, the High Noon metaphor involves fear – it shares this with the burning platform – but the metaphor, the image itself, is not so fear-inducing. We switch from a picture of a terrifying inferno to a man walking resolutely toward his destiny, doing what he thinks is right despite the risks, knowing the alternative is intolerable to him.

No metaphor is perfect – the reactions to the “burning platform” prove that. But “High Noon” may have the advantage of capturing the intense resolve to follow a new, difficult course of action with less risk of misinterpretation.

The Bottom Line

If you’re to lead major change successfully, you must create the conditions for your colleagues to experience a personal and collective “High Noon” moment. That’s when the unacceptability of the status quo and the preference for the new future crystallise into intense resolve. A resolve that overcomes all obstacles.

In the next instalment we’ll look at why appeals to reason and the logic behind the change idea aren’t usually enough to get people behind significant changes in direction.

The author is James Scouller, an executive coach. His book, The Three Levels of Leadership: How to Develop Your Leadership Presence, Knowhow and Skill, was published in May 2011. You can learn more about it at www.three-levels-of-leadership.com. If you want to see its reviews, click here: leadership book reviews. If you want to know where to buy it, click HERE. You can read more about his executive coaching services at The Scouller Partnership’s website.

August 1, 2014

Leadership & The Act of Will: Part 5

This is the last in a series of five blog articles on the act of will (to return to the first in the series click here).

The act of will is the art of figuring out what to do and getting it done. All leaders, ultimately, have to get things done and this is why it’s so helpful for them to understand that the act of will is a process with six stages.

The act of will is not just a matter of deciding or choosing, as some people think. There is more to it than that. Roberto Assagioli outlined the six stages of the act of will in his book, The Act of Will nearly fifty years ago. His six stages were:

1. Purpose (or aim or goal)/evaluation/motivation/intent

2. Deliberation

3. Choice and decision

4. Strengthening faith/conviction/certainty

5. Planning

6. Directing the execution

In this article, we’ll look at the fifth and sixth stages: Planning and Directing the Execution.

Stage 5: Planning

Now you need a plan. First, you’ll need to consider your starting point and pressures from any other goals you’re working towards.

With an especially complex or demanding goal you may have to consider alternative means of execution, their different phases and timings, and the money and support you’ll need from other people.

Here, the will can draw on the imagination to envisage different ways of achieving the plan before you assess the pros and cons and decide which make most sense. In other words, they may have to be a second stage of “choice and decision”.

It’s also important to consider in advance what may go wrong and how you’d respond if it did.

Finally, this is where you look at yourself and ask, “What habits do I have that may sabotage what I’m trying to achieve here… and what will I do about them?”

Stage 6: Directing the Execution

This is not the same as carrying out the plan; it’s directing it.

So the will directs execution by skilfully combining the powers of the mind, including its partner in the act of will, the imagination. Thus, it orchestrates your intuition, thinking and imagining plus the way you use your feelings and body sensations to communicate, connect with and influence others.

Direction includes (a) nudging the intellect to check the plan is on track; (b) ensuring problem-solving happens when it needs to; (c) adapting to new circumstances; and (d) seeing if surprise events demand a change of plan.

You could liken the will to the conductor of an orchestra. It’s not playing any of the instruments, but it’s having an effect on what music the orchestra plays and how it sounds.

That concludes this short series on the act of will. I hope you found it useful.

The author is James Scouller, an executive coach. His book, The Three Levels of Leadership: How to Develop Your Leadership Presence, Knowhow and Skill, was published in May 2011. You can learn more about it at www.three-levels-of-leadership.com. If you want to see its reviews, click here: leadership book reviews. If you want to know where to buy it, click HERE. You can read more about his executive coaching services at The Scouller Partnership’s website.

July 17, 2014

Leadership & The Act of Will: Part 4

This is the fourth in a series of five blog articles on the act of will (to return to the first in the series click here).

The act of will is the art of figuring out what to do and getting it done. All leaders, ultimately, have to get things done and this is why it’s so helpful for them to understand that the act of will is a process with six stages.

The act of will is not just a matter of deciding or choosing, as some people think. There is more to it than that. Roberto Assagioli outlined the six stages of the act of will in his book, The Act of Will nearly fifty years ago. His six stages were:

1. Purpose (or aim or goal)/evaluation/motivation/intent

2. Deliberation

3. Choice and decision

4. Strengthening faith/conviction/certainty

5. Planning

6. Directing the execution

In this article, we’ll look at the third and fourth stages: Choice & Decision and Strengthening Faith/Conviction/Certainty.

Stage 3: Choice & Decision

This is where, having deliberated, you choose one goal and let go of the others. This can be hard for those who dislike taking responsibility because of fear of failure or fear of making a mistake. It is the stage some mistakenly think is the act of will. But it’s not, it’s only one phase of it.

Stage 4: Strengthening Faith/Conviction/Certainty

This is the beginning of the action phase.

It’s where you must come to believe without doubt that you’ll succeed, giving you the energy to drive through to completion. You must have complete faith, complete conviction that despite obstacles, you will achieve your purpose – or at least, enough faith and enough conviction.

This stage is therefore about aligning your will and imagination. It’s crucial, because as I mentioned elsewhere, in any battle between the will and imagination, the imagination wins.

Faith largely depends on how we see ourselves – or rather, our beliefs about ourselves. People will vary in their degree of faith about the result depending, of course, on whether their self-beliefs allow them to believe they should even consider such a goal.

Conviction is different – it’s more intellectual; it stems from believing you will find the means to achieve the goal, that your faith is justified. Faith and conviction together bring the degree of certainty that you’re right to push ahead, allowing determined action.

This is why it can be essential to strengthen your faith and conviction through affirmation techniques, including mental rehearsal. But it’s not only about strengthening work. It’s also about seeing and dissolving negative beliefs standing in the way of the goal.

In my experience, this stage of the act of will is one many leaders ignore or don’t understand. Top sportsmen and women, however, are more likely to recognise its importance, especially if they work with a sports psychologist.

In part 5 we will look at the fifth stage: Planning.

The author is James Scouller, an executive coach. His book, The Three Levels of Leadership: How to Develop Your Leadership Presence, Knowhow and Skill, was published in May 2011. You can learn more about it at www.three-levels-of-leadership.com. If you want to see its reviews, click here: leadership book reviews. If you want to know where to buy it, click HERE. You can read more about his executive coaching services at The Scouller Partnership’s website.

July 5, 2014

Leadership & The Act of Will: Part 3

This is the third in a series of five blog articles on the act of will (to return to the first in the series click here).

The act of will is the art of figuring out what to do and getting it done. All leaders, ultimately, have to get things done and this is why it’s so helpful for them to understand that the act of will is a process with six stages.

The act of will is not just a matter of deciding or choosing, as some people think. There is more to it than that. Roberto Assagioli outlined the six stages of the act of will in his book, The Act of Will nearly fifty years ago. His six stages were:

1. Purpose (or aim or goal)/evaluation/motivation/intent

2. Deliberation

3. Choice and decision

4. Strengthening faith/conviction/certainty

5. Planning

6. Directing the execution

In this article, we’ll look at the second stage: Deliberation.

Now you may find yourself with alternative aims, all of which you find motivating. So before making a choice, you must decide which you prefer. This is deliberation.

It will probably centre on which aim is most important to you right now (that is, fits your values best).

It may also consider which goals are most realistic for you, whether this is the best moment to act, the rewards for achieving the aim and the penalties for missing it – for you and others.

This is when your beliefs about yourself, the world and other people will act as a filter as you deliberate. Thus, your limiting beliefs can and usually do affect your deliberations, ruling certain directions in or out. For example, if you believe yourself to be a victim of life, doomed to endure disappointment after disappointment, you’re less likely to consider bold, risky goals.

Of course, it’s also important to consider the problem that led you to seek a purpose in the first case and ask, which of the aims best deals with the issue? Finally, the deliberation stage is where you may ask others for their perspective and advice.

Sometimes the deliberation phase will demand you be ruthlessly honest with yourself to see your true motives; motives that may be more selfish than you’d care to admit – motives you wouldn’t act on once exposed. The trouble is, your limiting beliefs may have led you to create psychological defences that make it harder to see your true motives. Thus, it can sometimes be hard to stop yourself going after an unwise or harmful goal.

Deliberation can therefore be a complex stage in the act of will, demanding great insight.

In part 4 we will look at the third and fourth stages: Choice & Decision and Strengthening Faith/Conviction/Certainty.

The author is James Scouller, an executive coach. His book, The Three Levels of Leadership: How to Develop Your Leadership Presence, Knowhow and Skill, was published in May 2011. You can learn more about it at www.three-levels-of-leadership.com. If you want to see its reviews, click here: leadership book reviews. If you want to know where to buy it, click HERE. You can read more about his executive coaching services at The Scouller Partnership’s website.