From “Burning Platform” to “High Noon”

Post 1 of 4 in a series of articles on the subject of leading major large-scale change in organisations.

We start by considering the power and dangers of metaphors in leading change. Metaphors help in connecting with and influencing others because they distil the message in a vivid memorable way. But they can backfire. Let’s consider the example of the “burning platform”.

Origin of the “Burning Platform” Metaphor

Daryl Conner, an organisational change consultant, first used the “burning platform” metaphor in the late 1980s. It stemmed from the terrible 1988 Piper Alpha incident in which a drilling platform off the coast of Scotland exploded and became engulfed in fire, killing 167 people. Only 63 crew members survived. One jumped 15 stories from the platform into the water below to save his life. He commented afterwards, “It was either jump or fry. So I jumped.”

My First Encounter

I didn’t come across the “burning platform” metaphor until seven years later, in 1995, when reading a Harvard Business Review interview with Larry Bossidy, then CEO of AlliedSignal. When asked about the challenge of achieving change in a large organisation, he explained:

“I believe in the “burning platform” theory of change. When the roustabouts [oil rig workers] are standing on the offshore oil rig and the foreman yells, ‘Jump into the water,’ not only won’t they jump but they also won’t feel too kindly towards the foreman. There may be sharks in the water. They’ll jump only when they themselves see the flames shooting up from the platform… The leader’s job is to help everyone see the platform is burning, whether the flames are apparent or not. The process of change begins when people decide to take the flames seriously…”

Reading his words helped at the time because I was in my first role as a CEO. They made me realise I couldn’t lead change in an old-fashioned business that was in danger of sinking beneath the waves unless my colleagues were similarly uneasy about our trajectory. But it turns out the “burning platform” metaphor, although powerful, has caused misunderstanding, anger, criticism and resistance in some parts.

Misunderstandings

Daryl Conner intended the “burning platform” to be a metaphor for intense commitment; the resolve, the iron will to break the status quo and do something different from the past, something probably difficult or risky… and keep going. The idea was inspired by the man, Andy Machon, who, faced with the toughest of choices, saved his life by jumping from the oil rig.

Unfortunately, metaphors are so powerful that, once launched, they’re no longer controlled by their creators. And being vivid they can take on unintended meanings. With the “burning platform,” the imagery is so potent it can misdirect people’s attention.

Conner commented on this in a 2012 blog article. He’d realised that many people were focusing on the danger and fear evoked by the “burning platform” idea, not the sense of resolve and iron will he’d intended. This misunderstanding has led some executives to believe that:

People will only commit to large-scale change when they’re terrified of impending organisational disaster.

It’s a good idea for leaders to manipulate their colleagues – by lying, exaggerating or withholding data – into believing that urgent changes are needed even if they’re not.

Anger, Criticism & Resistance to the Idea

Misunderstandings aren’t the only problem. Some senior executives and consultants become critical, angry or resistant when discussing “the burning platform”.

There are those, for example, who believe the “burning platform” idea gives leaders the green light to compel people to do something they otherwise wouldn’t do. This angers them and they respond with statements like, “Real leaders don’t refer to a ‘burning platform’ when leading change” or “People won’t change by wanting to avoid an outcome; they change when they’re working towards something positive.”

Others with cooler heads don’t get so annoyed. Instead they point to the findings of neuroscience. They claim that when presented with a crisis of the kind depicted by the burning platform we activate the brain’s limbic system, which is associated with intense fear and the fight – flight – freeze response. They argue that this high level of anxiety and stress means we’ll think less clearly and therefore change will stall. Thus, they argue, the “burning platform” metaphor is counter-productive.

The critics say that if leaders want change they should rely not on fear, but appeal to reason and explain (1) the current circumstances (2) what must change and why and (3) why everyone will gain. But I believe they have failed to connect with Conner’s original intent and missed the deeper part of his message.

The Message Behind the Metaphor

That’s a shame because Conner was only searching for a vivid linguistic device to illustrate his message.

The message being that we need an unshakeable resolve, an ironclad commitment, to dare to act and follow through if major, large-scale change is to happen. The deeper message is that for such resolve to emerge, two conditions must be true:

First, that we’re dissatisfied with our present position or current trajectory.

Second, that we strongly prefer the newly defined goal or destination (vision).

The twin feelings of dissatisfaction (with the present state or anticipated result of following the same course) and desire (for the new future) are crucial. We need both. But in my experience – and according to 80 years of research by experts like Daryl Conner, Kurt Lewin, John Kotter and James Belasco – an intense commitment to change only emerges after initial dissatisfaction with the status quo. I’ll explore why that is in the second instalment of the series.

For now, all I want to say is that I’ve seen chief executives attempt to impose a new vision on colleagues who were happy with the way things were. Thus, their people asked themselves, “What’s wrong with where we’re heading, we’re doing fine as we are.” And guess what? They subtly undermined or even sabotaged the change initiatives, which fizzled out. The CEOs ignored the dissatisfaction side of the equation. They mistakenly thought the vision and perhaps their high rank would be enough to stimulate change.

So dissatisfaction with the status quo and desire for the new future are like two sides of the same coin: they are the twin forerunners of change. You could say they are the Yin and Yang of change – not polar opposites, but rather complementary forces that together drive sustainable change. But one (dissatisfaction) comes before the other.

A New Metaphor for Change

Can we find a new metaphor that captures Daryl Conner’s original intent while avoiding the unhelpful misunderstandings, criticism and resistance we’ve just discussed? I think we can.

The new metaphor I’m suggesting is “High Noon”.

Why “High Noon”?

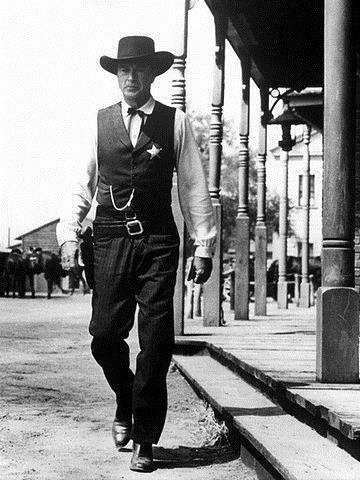

High Noon is a 1952 American Western starring Gary Cooper. He played a newly-married sheriff who’d decided to give up his badge to become a shopkeeper in another town. This was his last day in the job; he was planning to leave with his new wife on the noon train. Then he learns that a killer he’d brought to justice is out of jail and due to return on that same noon train, having vowed to kill him. To make matters worse, three of his gunslinger friends are meeting the killer at the station, leaving the sheriff up against four men.

High Noon – A Metaphor for Resolve

The townspeople are so scared of the killer and his gang that they won’t help the sheriff. And his new wife – a Quaker and pacifist – won’t let him stay and fight; she tells him she’s leaving on the noon train with or without him. What’s he going to do?

He could do nothing, ignore the problem and board the train with his wife before the four killers realise he’s gone. That way he avoids danger and pleases his new wife. The trouble is, he thinks the gang will hunt him down and, before they do, wreak revenge on the townsfolk.

In the end he makes an irrevocable choice and stays to fight the gang of four. And of course he wins. But – and this is crucial – he only does so with his wife’s help as she changes her mind, puts aside her religious beliefs, leaves the train, comes to his aid, kills one of the four and distracts another, enabling the sheriff to shoot him.

High Noon as a change metaphor represents resolve, steadfastness, the need to make an intense commitment to a new direction despite pressure to stay with the old course.

It recognises that for change to happen (abandoning the plan to leave and become a shopkeeper, risking the love of a new wife) we must feel both the unacceptability of the status quo (being pursued by the killers, letting them hunt down other townspeople) and the desirability of a better alternative (staying and confronting the gang, ending the problem, feeling he’s done the right thing and been true to himself).

Of course, some might see High Noon as a monument to an individual “lone wolf” attitude. But in fact the sheriff wasn’t alone in facing a High Noon moment. His wife was facing it too. In the end she decided to change, to let go of long-held principles and come to his aid. So it’s a story of collective High Noon. We must all feel we’re at a point of no return, we must all feel we have little choice but commit to cross the Rubicon. Although the intense commitment to change often starts in just one person or a small group, it must spread to a critical mass of people if it’s to succeed.

Every successful big change initiative must face its High Noon moment. Yes, the High Noon metaphor involves fear – it shares this with the burning platform – but the metaphor, the image itself, is not so fear-inducing. We switch from a picture of a terrifying inferno to a man walking resolutely toward his destiny, doing what he thinks is right despite the risks, knowing the alternative is intolerable to him.

No metaphor is perfect – the reactions to the “burning platform” prove that. But “High Noon” may have the advantage of capturing the intense resolve to follow a new, difficult course of action with less risk of misinterpretation.

The Bottom Line

If you’re to lead major change successfully, you must create the conditions for your colleagues to experience a personal and collective “High Noon” moment. That’s when the unacceptability of the status quo and the preference for the new future crystallise into intense resolve. A resolve that overcomes all obstacles.

In the next instalment we’ll look at why appeals to reason and the logic behind the change idea aren’t usually enough to get people behind significant changes in direction.

The author is James Scouller, an executive coach. His book, The Three Levels of Leadership: How to Develop Your Leadership Presence, Knowhow and Skill, was published in May 2011. You can learn more about it at www.three-levels-of-leadership.com. If you want to see its reviews, click here: leadership book reviews. If you want to know where to buy it, click HERE. You can read more about his executive coaching services at The Scouller Partnership’s website.