Alexander Jablokov's Blog, page 4

February 5, 2019

Life Without the Comfort of Sugar

I've been sleeping and working well lately. I'm trying not to take it for granted. I have rules, procedures, and habits that keep my life and productivity in line, but they are certainly much more effective when I already have a general tendency to do the right thing.

It’s pretty obvious when you see it like this

Before the start of last year, I read an essay by David Leonhardt, A Month Without Sugar, about how he does not consume added sugars during the month of January. As he points out in his column, that's harder than it looks, because sugar gets slipped into all sorts of processed foods, often under misleading names like "evaporated cane juice" or "malt syrup" (according to UCSF's sugarscience site, there are at least 61 names for sugar). It's in almost all bread, for example. And in the whole grain mustard I usually buy. And even in some frozen mixed vegetables I sometimes cook for breakfast.

So I did the no sugar thing for six weeks at the beginning of last year, and am doing it again this year. I kind of hope that this is not the cause of my recent clarity. I actually like bread, that mustard, and some other prepared foods, putting honey in my yogurt, and actual desserts as well. At this time of year hot cocoa is a big favorite, and I have not had any. Giving up sugar entirely is not something I'm aiming for.

My favorite breakfast since that first time, last year, is steel-cut oats cooked with milk and mixed with a sliced ripe banana I saute until brown and a tablespoon or so of peanut butter. I had been adding increasing amounts of sugar to my oatmeal before that, and knew that was not a good idea. This is just sweet enough for me.

Some people have some kind of transformative moment when they try sugar again, often realizing they no longer like sugar at all, or find things too oppressively sweet. I didn't, and don't expect to when I start eating it again. Trader Joe's Coffee Bean Blast ice cream was just as fantastic after my sugar vacation as it was before. Though, perhaps surprisingly, I have more control over how much of it I eat now. I do have pretty stringent portion control.

I've been cutting down on dessert for years now, so this last tastebud reset was mostly just a marginal improvement. Still, successive marginal improvements add up to big changes over time, the secret to any long-term lifestyle change.

Meanwhile, I have a couple of more weeks when I will beaver away, getting up early and being a generally annoying busy bee. That is, I would be annoying, but the only other current inhabitant of the house, my recently out of college son, does not get up before about 10 am, so the rest of humanity is spared. We'll see what happens when I make myself a cup of hot cocoa.

January 31, 2019

Legal Threats: Facing Theranos' Lawyers

Like most Americans, or at least most Americans of my race, class, and gender, what I fear most is not assault or loss of political rights (though I am definitely keeping an eye on those), but being involved in some kind of protracted legal dispute.

A lawsuit, which is almost always both lengthy and expensive, seems to me like the most horrific experience someone can go through without the actual fear of bodily harm. Lawsuits replace combat as a way of settling disputes, and the threat of violence has been replaced by legal action. The idea that some people indulge in them frequently seems insanely perverse.

To succeed, you need a good idea, chutzpah, and expensive lawyers

Elizabeth Holmes sees into your gullible soul

So that was what particularly struck me about John Carreyrou's Bad Blood, the story of Elizabeth Holmes and the bizarre fraud of Theranos: the terrifying lawyers, the brutal NDAs, the harassment, and the legal threats that faced anyone who crossed Holmes and her partner/BF Sunny Balwani.

First off: tremendous book, totally fun, both informative and entertaining. I listened to the audio, but whatever the format, you won't be disappointed.

Partway through the book, the author, Carreyrou, appears as a character, describing how he first heard of the story, how he researched it, how he reported it. At first this seems odd. "How I got the story" is kind of a tyro journalistic approach.

Carreyrou as a character in the dramaBut there was a good reason for doing it this way, because only part of the story is digging into Theranos' claims, malfunctioning gadgets, and breathtaking "fake it 'till you make it" attitude. The rest of it is the savage reaction of Holmes and Balwani. They made many attempts to stop the publication of Carreyrou's first piece in the Wall Street Journal, up to lobbying the WSJ's owner, Rupert Murdoch, an investor in Theranos, to kill the story. To his credit, he upheld the wall between business and editorial.

Like most things, this has been going on since ancient Sumer

Imagine being a regular person, skilled at your job, happy to be working at a place that seems to be doing cool things, and then slowly realizing that nothing is as it seems, and you are, in fact, party to a tremendous fraud. But when you try to tell someone about it, you discover that the non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) that you signed forbid you to discuss anything you learned, and that they contained non-disparagement clauses that leave you open to legal action if you criticize your former employer in any way.

Eventually this all came out, through Carreyrou's dogged reporting. But what struck me was the fact that this was a high-profile company with a non-functioning product, which did attract the attentions of a top journalist. What about other employees, and lower profile companies, who have signed similar agreements?

How much more of this is there?How often does this go on? Now, it would be silly to claim that corporate litigation is some kind of sign of our decadent age. Inventors, investors, and customers have all be merrily suing each other for centuries, sometimes in cases that stretched for decades. Some people think that after their historic flight at Kitty Hawk, the Wright Brothers settled down to a career as patent trolls, not really bothering to invent anything else (note that there are those who dispute this characterization).

But aside from the fraud, the implacable legal threats were the most fascinating part of the story. It gives one pause to think of how many horrendous stories are kept silent by CEOs and companies that are just a bit less mediagenic and visible than Elizabeth Holmes and Theranos, but equally ruthless.

How many lawyers do you have on retainer?Dismaying to think how many one-lawyer businesses there are in this country.

January 29, 2019

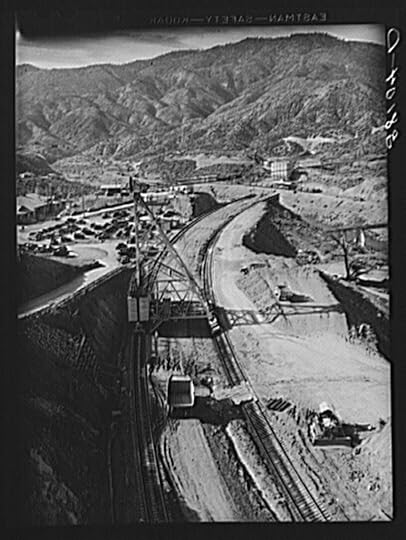

Alien robots at Shasta Dam: the Untold Story

I was just checking Shorpy over the weekend, when I was struck with this image of robots coolly firing at the Army troops desperately holding them off. As I remember, this happened around 1940, but was suppressed because rising tensions with the Japanese took priority. The robots were eventually domesticated, and used for construction purposes.

(Click to open a larger view on the Shorpy site)

I love the angle of the photo, by Russell Lee, for the Farm Security Administration.

What they actually are is almost as interesting. Shasta Dam was concrete. A large central tower was built next to the concrete plant. It was connected by cables to a total of seven towers like the two above, which actually moved on tracks, as you can see in the image below.

One of the moveable towers from a different angle

Large buckets were filled with concrete at the plant, then cranked across to one of the towers, where it was dumped to form blocks fifty feet square and five feet deep, which make up the dam. I don’t know how often this particular method was used to build dams, but it has a real dieselpunk charm.

The mama robot feeding her young

Lee’s photograph of the dam under construction is itself a wonderful image, worth clicking through to Shorpy to see in full.

Shasta dam under construction

January 17, 2019

Finicky language choices in my new story

The tech in my story is a bit cheesier than this cover story’s

I have a novella in this month’s issue of Asimov’s Science Fiction magazine, “How Sere Looked for a Pair of Boots”, a story in my City of Storms series.

Asimov’s has a blog, From Earth to the Stars, and yesterday I had a post in it, “Language Usage in ‘How Sere Looked for a Pair of Boots’”, about the reasoning behind some specific word choices I made in the story.

Am I selling this? It’s one of those “how the sausage gets made” pieces, and YMMV, but if that kind of thing does pique your interest, do check it out.

January 15, 2019

Things Maps Don't Tell Us

When it comes to conveying visual information clearly, a line drawing is often the best choice.

Of course, good informational line drawings require a specific set of skills. Aside from meticulous draftsmanship, you need subject matter expertise—you have to know exactly which aspects of what you are drawing are most important, and how to convey that importance to the reader.

Years ago, I found a book in my boyhood public library, The LaGrange Public Library, that fascinated me: Things Maps Don't Tell Us: An Adventure Into Map Interpretation, by Armin K Lobeck. It was published in the year of my birth, 1956.

This was decades before I managed to gin up any enthusiasm for geology (now a particular interest). But the book seemed to pull the curtain back on certain secrets of the physical world that no one had so clearly revealed before. And that revelation came visually.

That that earnest subtitle ("adventure" is definitely overpromising) didn't put me off will tell you something about my more earnest younger self.

Why the world looks the way it does

Lobeck's method of explanation is both simple and subtle. He wants us to understand that the flow of rivers, the shape of islands, the location of cities, the routes of highways, and the shapes of lakes are caused by the underlying geology.

So he classifies the patterns by their underlying causes. Peninsulas, for example, can be sand spits of various kinds, cuestas resulting from tilted rock layers, eroded deltas, or many other things. But on a typical map, all you see is the shape. He describes the underlying causes of specific coastlines, river patterns, lakes, and many other formations.

The way he teaches you about these is by showing two facing pages on each two-page spread of the book. The left hand page shows what the landscape looks like as shown on some regular map, some showing an entire continent, some a much smaller area. He removes any extraneous features in his simplified sketch version. On the right hand side is a diagram of what causes led to those particular shapes, patterns of rivers, or whatever.

For example, here is his explanation of two peninsulas in the Great Lakes: Door Peninsula in Wisconsin, and the Bruce Peninsula (called Saugeen Peninsula on the map). On the left hand map, they are, well, just peninsulas, land surround on three sides by water.

If you heard me talk, you’d here that my accent marks me as coming from this area

But the right hand map (and the crisply detailed explanation I have not included) shows how the downcurved layers of the Michigan Basin come up in curving ridges, ridges that, due to glaciation, now are surrounded by water. He points out the circular pattern of the formations around Lakes Huron and Michigan. Not just these two peninsulas, but islands, Green and Georgian Bays, and the shapes of the Great Lakes themselves.

Suddenly it all makes sense

That's just a taste of a book that has 72 examples of this sort in total, some of them including multiple places in the world. It's really a nice way to get a knowledge of landforms, and it's something I often refer to when trying to figure out some fictional landscape.

And you can see how Lobeck's eye and hand have made things clearer for us that anything else could.

If you want another example of Lobeck's work (not from the book), here is his map of Kentucky.

I want one of these for every place

I could use maps of other complex areas, the Caucasus for example, to help me understand the history of the area. I have yet to find any.

January 10, 2019

Grief and intellectual absolutism

I’m reading Anne Somerset’s Queen Anne: The Politics of Passion, another consequence of my viewing of the movie The Favourite (my review here). So far, it’s nicely written, detailed but not a grind, and an interesting insight into what happens when a really normal person with some health problems becomes monarch of a significant kingdom. It’s also an insight into the precarious feeling of the political environment after the Glorious Revolution. That James II’s son and Anne’s half brother, James Edward Francis Stewart, the Pretender, might actually become King was a real possibility.

Sarah Churchill, Duchess of Marlborough, meditating on how to get back at someone

As The Favourite shows, a lot of Anne’s emotional life was tied up with Sarah Churchill, Duchess of Marlborough. They had been close since Sarah was 13 and Anne eight, when Sarah became a maid of honour to Mary Beatrice of Modena, second wife of James II, Anne’s father (this was in 1673, long before he had his brief run as king).

The formerly close relationship ended in the early 1700s, during Anne’s reign. Though intelligent and witty, Sarah had always been hard to get along with. She became an ardent Whig, while Anne leaned Tory. Sarah would not leave this alone.

The historical significance of the deaths of childrenIn 1703, Sarah’s only surviving son, John, caught smallpox at Cambridge, and died. Sarah was overcome with grief, and, even though Anne had suffered her own griefs, with a son who had died at 11 and a number of children who had died young or been stillborn, this did not lead Sarah to a common sympathy with her. In fact, according to Somerset, “…Sarah’s grief had acquired a competitive edge. She came to believe that Anne’s suffering when her children died had not been nearly as intense as hers.”

Most of us have known someone like that.

But it seems that the grief had a significant effect on her personality:

Sarah’s bitterness at the loss of her only son stifled her generosity of spirit. Now, intolerance and inflexibility, became her dominant traits. By her own account, she had never derived much emotional satisfaction from her friendship with Anne, but henceforth it was validated in her eyes principally by her belief that she must mould Anne to her will and thus aid not only her husband [the Duke of Marlborough] and Godolphin [First Lord of the Treasury] but also the political party she favored [the Whigs]. Finding in politics an outlet that distracted her from her grief, Sarah devoted herself to it with febrile energy, seeing things in absolute terms that left no room for nuance. It became increasingly hard for her to accommodate any form of disagreement, or to concede that other people’s beliefs had any legitimacy at all.

It made her a familiar tiresome partisan. How often are these inflexible people riven with grief, or some other strong emotion or experience that has eroded parts of their personality? I don’t know that this is a common cause of tiresome political absolutism, and even knowing its very real cause couldn’t have made Sarah anything but a real pain to deal with, but it is an interesting thing to think about.

Sarah never recovered her old personality, though she lived until age 84. I think it is probably vain to think that any of our more pointlessly ardent political absolutists will either.

What effect have personal tragedies and experiences had on the way you relate politically?And do you really think you are able to tell?

January 8, 2019

Constants of Civilizational Collapse as Explained by T. B. Macaulay

When I am bored, frustrated, or distracted, I sometimes comfort myself with the mandarin prose of the 19th century historian Thomas Babington Macaulay. His lengthy but balanced sentences, his piercing (if sometimes show-offy) erudition, and the clarity and firmness of his positions always calms me down with a sense of Victorian certainty.

Yesterday I was looking at his essay on “War of the Succession in Spain”. After seeing The Favourite ( my reaction to the movie here), I renewed my interest in the late Stuart period and its virulent political polarization. Rumbling beneath the action of the movie are the battles of the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714), and their costs.

Charles II, the inbred last Hapsburg King of Spain, whose death without heirs started the War of the Spanish Succession

As it happens, Macaulay wrote a review of a book by Lord Mahon, History of the War of the Succession in Spain, and I decided to goof off by reading it. As with all Macaulay essays, he spends a little time on the book and its author, then goes off to tell the real story, the one the author somehow cloddishly missed in their urge for publication. Mahon does not come off that well.

But Macaulay, a man with a real sense of the political, an ardent Whig, with all the devotion to political progress that implied at the time, can really dig into the underlying themes of history. He spends some time describing the vast power and culture of Spain in its heyday, when it ruled nations around the world. Then he goes through the political collapse that led to its becoming a battleground for other rising powers. For his emotional reaction, he somewhat sardonically quotes Isaiah: “But how art thou fallen from heaven, O Lucifer son of the morning! How art thou cut down to the ground, that didst weaken the nations!”

“All the causes of the decay of Spain resolve themselves into one cause, bad government.”After Macaulay tells us that, he provides an obituary not just of Imperial Spain, but of any nation that is not careful to maintain its political institutions:

The effects of a change from good government to bad government are not fully felt for some time after the change has taken place. The talents and the virtues which a good constitution generates may for a time survive that constitution. Thus the reigns of princes, who have established absolute monarchy on the ruins of popular forms of government often shine in history with a peculiar brilliancy. But when a generation or two has passed away, then comes signally to pass that which was written by Montesquieu, that despotic governments resemble those savages who cut down the tree in order to get at the fruit. During the first years of tyranny, is reaped the harvest sown during the last years of liberty.

That’s worth reading carefully. There’s a lot in this paragraph. I think his observation, that burning the stored power of a state can give a very bright light, is key to some of what we are experiencing now.

Not every prognostication of doom and destruction resonates with our current political moment, no matter what people may claim, but this one certainly does. Institutions take constant, unrewarding, and often frustrating maintenance. As always, maintenance receives no great plaudits. It is the province of those who hold doing their duty as the highest good, and who rely on the respect and cooperation of those who understand how important their quiet hidden work is.

Beware the leader who cuts down the long-maintained fruit tree and says, “It used to be hard work to get at that fruit, but I alone have made it easy for you, my people.” And, yes, “savages”, probably did not do this, unless they were raiding someone else’s orchard, but the point stands.

January 3, 2019

"The Favourite": a Glamorous and Savage Look at Court Culture

The Favourite is a clinical examination of hothouse Court politics during the reign of Queen Anne (the first decade of the Seventeenth Century). It is sometimes billed as a comedy. Though it does have some funny bits, it ends in neither a wedding nor a funeral, but in a kind of psychic immurement, so take your pick.

Anne doesn’t seem to have a great grip on either orb or scepter, but that’s just lack of artistic skill, not metaphor

Miss E and I both loved it. So, really, a good date movie. Men, if you're looking for battlefield scenes, this is no Barry Lyndon—incidentally, the first movie where interiors were filmed solely by candlelight, a style shown to great effect in The Favourite. But watching three brilliantly acted sparring women, any of whom could eat you alive, definitely has its charms. The psychic violence is right near the surface. And all the sex is, in some way, also about power and manipulation (once, um, literally). What more could you ask for?

As always, your dating mileage may vary, and I make no guarantees.

Plus, it has some brilliant set pieces, like the absurd dance sequence that shows Queen Anne that she is physically increasingly unable to enjoy anything about life even as it makes everyone else seem like some kind of Olympic athlete. This clip is annotated with what they called the various moves during shooting.

Is historical fiction more like history or like fantasy?

I'm sometimes curious about the place of historical fiction in a world where history is so little known, even among the educated classes. In some ways, The Favourite could have been set in any court, since the roiling world outside the palace where modern science and literature were in the process of being invented never plays much of a role. But the characters were real and interesting, and misbehaving English-speaking royals are always of interest.

Movies set in this era (I'm thinking particularly of The Draughtsman's Contract, an acknowledged influence on director Yorgos Lanthimos) always love the huge wigs, the foppish dress, and the ludicrous and childish misbehavior on the part of aristocrats, in this case duck racing and pelting laughing fat men with fruit. Silent slo mo always helps make these activities seem more compelling than they could possibly have been.

The costumes are inspired by historical ones but have a a modern feel to them. The endless hallways and chambers of the palace have an almost Gormenghast feel to them. A character is poisoned and then imprisoned in a dismal whorehouse (a movie like this could scarcely show any other kind), which is actually the only other interior location shown.

I'm not a huge fan of much historical fantasy fiction, but if more if it was like this, I might change my mind. I'm willing to be enlightened if anyone has any suggestions for me.

How women could exert power

Historically, ambitious women who sought to influence events lacked access to the violence and coercion that lie underneath the exercise of power, and so were forced to rely on emotional manipulation and sex. Men, who did have violence at their disposal, always found this contemptible, even as they found themselves responding.

Sarah Churchill, played with self-confident aplomb by Rachel Weisz, is an actual player in politics, helping manage the finances of the War of the Spanish Succession on behalf of her husband, the Duke of Marlborough, and via her access to Queen Anne. Marlborough keeps winning increasingly bloody and expensive battles, but battlefield defeats are not enough to force France to sue for peace. Parliament is growing restive, facing tax increases to finance an increasingly expensive, stalemated war.

Abigail Masham, introduced into the palace by her relative Sarah, is destitute, without any power at all. She manages to gain Anne's trust and affection, makes a favorable if loveless marriage, and gains power in the palace.

The result is a power struggle for emotional control of the sad, ill, sometimes befuddled, sometimes surprisingly shrewd Anne, who is less easily controlled than either would-be puppetmaster thinks.

The movie gets the hothouse court atmosphere down, though with perhaps a bit more fisheye lens action than necessary. This is the era when once-powerful French nobles struggled for the privilege of collecting Louis XIV's chamberpot. Tiny privileges loom larger than military victories, long emotional sieges can lead to sudden changes in status, and taking your eye off the ball for any length of time can lead to personal disaster. It would be nice to achieve power and wealth some other way, but this is pretty much the only game in town.

A one point late in their conflict, Sarah Churchill realizes something about her rival, Abigail Masham: "We're playing different games". And it's true. At story start Abigail has nothing but a connection to her more powerful cousin. She is scrabbling desperately for survival. Sarah is playing the larger game of state and international politics. In the end Abigail achieves...well, you should see the movie to see what she achieves. It's a brilliant vision of balancing what you want versus what you're willing to give up.

The game is hard fought, and the outcome is in doubt until the very end. And maybe past it. I was actually startled by how much I enjoyed it.

What genre do you think The Favourite is?

I think of it as historical fantasy without the tedious magic. You can pour horror, suspense, and political intrigue into that bucket without missing a drop.

January 1, 2019

My Arisia, January 18-20, 2019

I’m going to be at Arisia, a Boston convention, over MLK weekend. Instead of the Westin Seaport, where it has been for a few years, it will be at the Boston Park Plaza

As usual, I’ll be doing a few chin-stroking panels. I like to make them entertaining, but if you lack the stamina to watch four SF writers expound on some topic of intense interest to them, do find me elsewhere (like the bar). Or, better yet, find me and take me to a bar.

But I will have opinions about things:

Embracing the Alien: Writing Believable ETs Saturday January 19, 10 AMI’ve been writing a lot of aliens recently, after not doing it for awhile. I hope someone has clever suggestions I can steal.

Fellow panelists:

Timothy Goyette mod

Ruthanna Emrys

James L. Cambias

Walter H. Hunt

Yeah, we don’t even understand the present, so how can we write about the future? Why does the future still have people sitting in a row talking about a topic?

Also starring:

Trisha J. Wooldridge mod

James Hailer

Debra Doyle

Alex Feinman

I remember the transformative horror of the last time I was on a flashback panel…..

Unindicted co-conspirators:

Gillian Daniels mod

Debra Doyle

Leigh Perry

Amy J. Murphy

Hope to see you there. And if you are a co-panelist who has ended here because you were checking on who else in the world was talking about you, hope to see you there as well.

Oh, and happy new year 2019! Let’s see if we manage to live through this one.

December 27, 2018

Doing the Locomotion: Saratoga Spring and New York City

A few more Shorpy photographs of people walking, these focused a bit more on male style.

Dress like you mean it

I do tend to notice men's dress, and here are a couple of good examples.

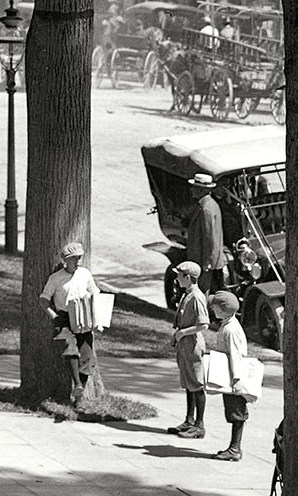

The end of the Nineteenth Century was right about now

The coolest man in town

Saratoga Springs is a resort town, known for its horse racing. Here is everyone strolling in the shade of the elms, in 1915.

I’d love a look at the headlines

This couple is quite elegant, but I think the male far outshines his mate. Everything about him is sharp.

Meanwhile, right behind them: newsies! They really did dress like that. The more sophisticated older one is leaning casually against a tree, leg up, while the younger ones try to impress him with their street smarts.

Everyone has somewhere to be

Not just the clothes, but how you wear them

Finally, the heart of purposeful walking, New York City. Here is a picture of the intersection of Seventh Avenue and West 125th, in 1938. Again, a lot of people, but I love this other gracious gentleman. Both he and the boulevardier in Saratoga Springs show that it's not just the clothes, but the way that you wear them. And, really, a hat helps, even though that is no longer permissible, and just makes you look like you're losing your hair.

Where is she going tonight?

But I also always like this cheerful lady right behind him. I wish I knew her.

I wish I knew them all, and it is a bit chilling, sometimes, to realize that they are all long dead.

Do you look at pictures of the past?What kind of thing do you look for when you do? I also look at machinery, architecture, and trains.