Alexander Jablokov's Blog, page 2

August 4, 2020

...

I recently read Strange Victory: Hitler's Conquest of France, by Ernest R. May, about the Fall of France in 1940. May has written a number of books about executive decision making in foreign policy and intelligence assessment. Strange Victory is very much about that. May gives you an excellent view of the constraints facing the various participants, the constraints they thought they faced and maybe didn't, and how events can seem to go with glacial slowness, only to suddenly accelerate without warning.

On September 1, 1939 France and Britain, having promised to do so without anticipating that they would really have to follow through (the point was to dissuade Hitler from going ahead, they didn't really expect to have to do it), declared war on Germany in response to its invasion of Poland.

But then they didn't really do very much. There is some reason for this, there were a number of difficulties, but they both futzed around from then until May 10, 1940, blaming each other for things, when Hitler decided put an end to their prevarication.

So it's interesting to contemplate some of the problems facing Edouard Daladier, France's prime minister, after the declaration of war:

The autumn of 1939 had been frustrating for Daladier. He had tried to form a national government, hoping that in wartime he would not have to continue formulating every act or decree like a pharmacist preparing a complicated prescription. With the goal of at least having his own Radical Socialist Party [despite the name, a centrist party] united behind him, he asked Herriot, his old mentor and rival, to replace Bonnet as foreign minister. But Herriot said he would serve only if the cabinet also included Marshal Pétain, and Pétain refused to serve with Herriot on the ground that Herriot's appointment as foreign minister would alienate Mussolini and Franco. Socialist leaders also refused to serve either with one another or without one another. Paul Faure, himself ineligible because a pacifist and unregenerately munichois [as appeasers were known after the Munich agreement of 1938], swore to oppose a cabinet that contained Léon Blum or any socialist on Blum's side. He reportedly said that, if Blume entered the government, "then all Israel with him! That would be war without end!" [no surprise, Faure ended up serving Vichy, Blum in Buchenwald]. Faure and Blum alike threatened to vote against a cabinet that included anyone from the right; Flandin and others linked to employers' groups vetoed inclusion of even a moderate trade-union leader.

Soon after, Daladier yielded the premiership to Paul Reynaud—but Reynaud had to retain almost all of Daladier's cabinet, including Daladier as both minister of defense and minister of war. That's cabinet politics in the twilight of the Third Republic.

The closer you look at history, the less clear its lessons seem to be, and the more complex and tangled the lines of causation. May sees France's (and Britain's) failure as largely down to poor acquisition and management of intelligence. I'll try to take a look at that in a bit.

June 2, 2020

The poetical joys of Byzantine hierarchy

Steven Runciman's The Great Church in Captivity, is, as its subtitle explains, "A study of the patriarchate of Constantinople from the eve of the Turkish conquest to the Greek War of Independence". But it is actually more than that, because its first seven chapters, roughly 40 percent of the book, are a detailed explication of the Orthodox Church, its theology, structure, movements, and relations with the West.

Yeah, kind of a specialist read, and not the best introduction to Eastern Orthodoxy if you aren't familiar with it. Still, I have a weakness for Byzantine official titles, and while detailing Byzantine administration Sir Steven manages a magnificent hierarchical aria:

...five great offices remained throughout the Byzantine period. They were headed by the Grand Economus, who was in charge of all properties and sources of revenue and who administered the Patriarchate during an interregnum; by the Grand Sacellarius, who, in spite of his title, had nothing to do with the Purse but was in charge of all the Patriarchal monasteries, assisted by his own court and a deputy knows as the Archon of the Monasteries; by the Grand Skevophylax, in charge of all liturgical matters, as well as of the holy treasures and relics belonging to the Patriarchate; by the Grand Chartophylax, originally the keeper of the library but, after the disappearance of the Syncellus and the Archdeacon [vanished offices discussed earlier], the Patriarch's Secretary of State and director of personnel; and finally by the Prefect of the Sacellion, keeper of the Patriarchal prison and in charge of the punishment of ecclesiastical offenders. These five officials were members of the Holy Synod and ranked above all metropolitans [that is, bishops of large metropolitan sees].

If you survived that, you may well enjoy the book. But even I limit myself to small doses, lest I faint from the smell of frankincense.

December 3, 2019

In Search of the Boston Green Head, Part One: Basanite, Bekhen Stone, and the Wadi Hammamat

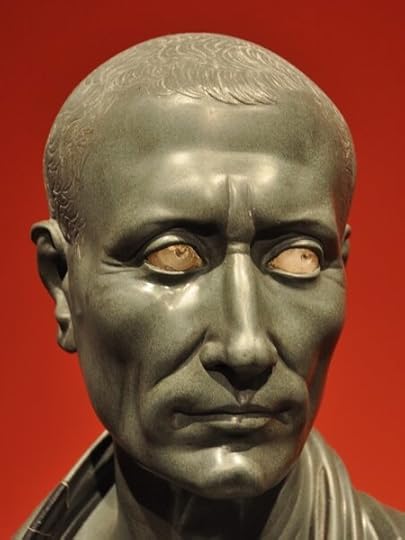

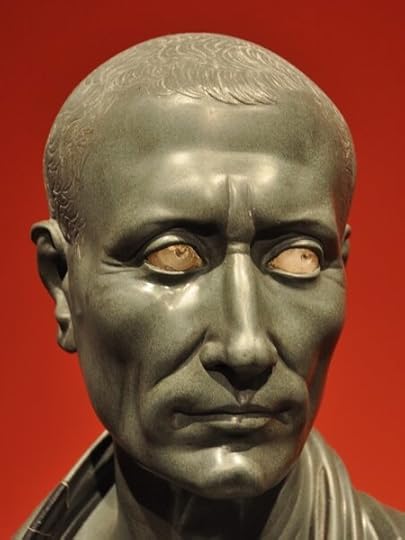

A moody and weird Julius Caesar, probably Egyptian, probably from the century or so after his death

This is the first of several posts related to a particular type of stone, and a small bust of an Egyptian priest made from that stone, in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

A few years ago I was browsing through Philip Matyszak's Chronicle of the Roman Republic (a series of short biographies of various figures during that era, with informative sidebars, stemmata, and timelines, it is made for browsing, at least if you are a Roman history geek), when I came across a picture of this striking bust of what is most likely Julius Caesar, in Berlin.

The caption in the book says it is carved from green "basanite", a stone from Egypt. Clearly the stone is sculpturally useful, dense, hard, of consistent texture, capable of being smoothed, and of striking color.

I've written about sculpture before, and am toying with a book about a sculptor in the late 19th century. So I was curious: what is basanite? Sculpture is the encounter between an idea and a specific physical reality. Well, OK, that describes art in general, but it seems clearest in the case of sculpture, whether stone, wood, metal, or clay, each of which is a demanding partner in the work.

But the identity of basanite is not as easy a question to answer as you might think.

The mysteries of geologic nomenclature

The stone in question is not always called basanite, and the history of the word "basanite" itself can cause confusion as well—after you read my detective work, I will reveal that the criminal is actually someone completely different. The material of the bust called the Green Caesar is sometimes described as greenschist, slate, or greywacke.

As we shall see later on, there is a completely different stone, an igneous extrusive called basanite, and which confused me for a long time. Here, "extrusive" just means the igneous rock formed on the surface, rather than underground. Confusingly to laypeople, geologists often give completely different names to the extrusive and intrusive versions of otherwise identical rocks—for example, what is granite when it forms deep underground is rhyolite if it forms on the surface. This igneous basanite is very much like basalt (an extrusive igneous rock whose intrusive version is called gabbro, if you must know).

There are also historical reasons this rock is called basanite, but the rock the head is made of is something else entirely. For now, I will call that stone "sculptural basanite" (a term of no validity outside this blog post—let it be our secret), though I will come up with a more precise name a bit further on, though be warned that that name will be just as much of a local variable as sculptural basanite.

On the track of sculptural basanite

In The Materials of Sculpture (an informative book covering stone of all kinds, as well as ivory, bronze, clay, and wax, among other things) Nicholas Penny says

The most highly prized Egyptian stone to be employed for sculpture on a large scale was basanite, commonly confused with basalt (and still usually described as such on museum labels [the book is from 1993]). This is a "greywacke", a by-product of the decomposition of basaltic rock.

"Decomposition" is geologically imprecise, but this places the stone at its place of origin, Egypt, and also demonstrates how the terminology can be vague or confused (it is the other kind of basanite that can be confused with basalt). Unfortunately for interested amateurs like me, geology has no equivalent of a species, where there is only one name for one thing, and the first discoverer gets absolute naming priority. Rock types are not even as clear a species, and it feels like there was always a lot of competitive naming going on in geology, with everyone convinced that the rock in their mountains was quite different than that allegedly similar rock in those mountains some sadly lame earlier geologists wasted their time investigating.

In "The building stones of ancient Egypt – a gift of its geology" (PDF), Klemm and Klemm say

green siltstones, dark green greywackes and conglomerates, which are best exposed in the Wadi Hammamat...[where] an impressive quarrying activity is documented by almost 600 rock inscriptions over a time interval from Predynastic until the late Roman period (about 4000 BC until 300 AD). These many inscriptions concentrated along a relative short distance in the wadi obviously indicate the uniqueness of this site and its extraordinary importance to ancient Egyptian culture. Consequently the rock type extracted here received a special name: ‘‘Bekhen-stone’’, as reported in many ancient Egyptian documents.

This Bekhen-stone is the basanite I got interested in. The Wadi Hammamat, far off in the Eastern Desert, required long overland transportation to the Nile, under difficult, waterless conditions. But I am not alone in being struck by the character of this stone:

Particularly the very dense, medium-grained dark green greywacke was used during the entire Pharaonic era and on until the Ptolemaic (Greek) period (from 332–30 BC), mainly for sarcophagi, archetraphes [sic— I'm assuming they mean "architraves", but am not sure] and for the finest carved sculptures of Egyptian antiquity. Scattered unfinished or broken sarcophagi indicate that at least the raw form of these vessels were worked out at the quarry site, which is understandable as they had to be transported over 90 km through the desert, until shipped on the river Nile to their final destination.

Most of the royal sarcophagi of the [Old Kingdom] and about 100 sarcophagi for private individuals of the Late Period (since 600 BC) and of Ptolemaic and Roman times were made of this rock variety.

Wadi Hammamat should totally be more famous

The Wadi Hammamat is totally cool, historically, geologically, and geographically, and has to have been the setting for some historical fantasy or other. Anyone know of one? My reading in that genre is pretty sparse.

OK, that's enough for now. Next time, we finally distinguish sculptural basanite from basalt, and then have a look-in on its dark twin, sculpturally useless igneous basanite. I bet you can't wait.

...

A moody and weird Julius Caesar, probably Egyptian, probably from the century or so after his death

This is the first of several posts related to a particular type of stone, and a small bust of an Egyptian priest made from that stone, in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

A few years ago I was browsing through Philip Matyszak's Chronicle of the Roman Republic (a series of short biographies of various figures during that era, with informative sidebars, stemmata, and timelines, it is made for browsing, at least if you are a Roman history geek), when I came across a picture of this striking bust of what is most likely Julius Caesar, in Berlin.

The caption in the book says it is carved from green "basanite", a stone from Egypt. Clearly the stone is sculpturally useful, dense, hard, of consistent texture, capable of being smoothed, and of striking color.

I've written about sculpture before, and am toying with a book about a sculptor in the late 19th century. So I was curious: what is basanite? Sculpture is the encounter between an idea and a specific physical reality. Well, OK, that describes art in general, but it seems clearest in the case of sculpture, whether stone, wood, metal, or clay, each of which is a demanding partner in the work.

But the identity of basanite is not as easy a question to answer as you might think.

The mysteries of geologic nomenclatureThe stone in question is not always called basanite, and the history of the word "basanite" itself can cause confusion as well—after you read my detective work, I will reveal that the criminal is actually someone completely different. The material of the bust called the Green Caesar is sometimes described as greenschist, slate, or greywacke.

As we shall see later on, there is a completely different stone, an igneous extrusive called basanite, and which confused me for a long time. Here, "extrusive" just means the igneous rock formed on the surface, rather than underground. Confusingly to laypeople, geologists often give completely different names to the extrusive and intrusive versions of otherwise identical rocks—for example, what is granite when it forms deep underground is rhyolite if it forms on the surface. This igneous basanite is very much like basalt (an extrusive igneous rock whose intrusive version is called gabbro, if you must know).

There are also historical reasons this rock is called basanite, but the rock the head is made of is something else entirely. For now, I will call that stone "sculptural basanite" (a term of no validity outside this blog post—let it be our secret), though I will come up with a more precise name a bit further on, though be warned that that name will be just as much of a local variable as sculptural basanite.

On the track of sculptural basaniteIn The Materials of Sculpture (an informative book covering stone of all kinds, as well as ivory, bronze, clay, and wax, among other things) Nicholas Penny says

The most highly prized Egyptian stone to be employed for sculpture on a large scale was basanite, commonly confused with basalt (and still usually described as such on museum labels [the book is from 1993]). This is a "greywacke", a by-product of the decomposition of basaltic rock.

"Decomposition" is geologically imprecise, but this places the stone at its place of origin, Egypt, and also demonstrates how the terminology can be vague or confused (it is the other kind of basanite that can be confused with basalt). Unfortunately for interested amateurs like me, geology has no equivalent of a species, where there is only one name for one thing, and the first discoverer gets absolute naming priority. Rock types are not even as clear a species, and it feels like there was always a lot of competitive naming going on in geology, with everyone convinced that the rock in their mountains was quite different than that allegedly similar rock in those mountains some sadly lame earlier geologists wasted their time investigating.

In "The building stones of ancient Egypt – a gift of its geology" (PDF), Klemm and Klemm say

green siltstones, dark green greywackes and conglomerates, which are best exposed in the Wadi

Hammamat...[where] an impressive quarrying activity is documented by almost

600 rock inscriptions over a time interval from Predynastic

until the late Roman period (about 4000 BC until

300 AD). These many inscriptions concentrated along a

relative short distance in the wadi obviously indicate the

uniqueness of this site and its extraordinary importance

to ancient Egyptian culture. Consequently the rock type

extracted here received a special name: ‘‘Bekhen-stone’’,

as reported in many ancient Egyptian documents.

This Bekhen-stone is the basanite I got interested in. The Wadi Hammamat, far off in the Eastern Desert, required long overland transportation to the Nile, under difficult, waterless conditions. But I am not alone in being struck by the character of this stone:

Wadi Hammamat should totally be more famous

Particularly the very dense, medium-grained dark

green greywacke was used during the entire Pharaonic

era and on until the Ptolemaic (Greek) period (from

332–30 BC), mainly for sarcophagi, archetraphes (sic— I'm assuming they mean "architraves", but am not sure) and

for the finest carved sculptures of Egyptian antiquity.

Scattered unfinished or broken sarcophagi indicate that

at least the raw form of these vessels were worked out at

the quarry site, which is understandable as they had to

be transported over 90 km through the desert, until

shipped on the river Nile to their final destination.

Most of the royal sarcophagi of the [Old Kingdom] and about

100 sarcophagi for private individuals of the Late Period

(since 600 BC) and of Ptolemaic and Roman times were

made of this rock variety.

The Wadi Hammamat is totally cool, historically, geologically, and geographically, and has to have been the setting for some historical fantasy or other. Anyone know of one? My reading in that genre is pretty sparse.

OK, that's enough for now. Nest time, we finally distinguish sculptural basanite from basalt, and then have a look-in on its dark twin, sculpturally useless igneous basanite. I bet you can't wait.

October 29, 2019

Musical imitations as their own form of art

Composers often play around by inhabiting an older style of composition. This seems to be particularly true of the modernists of the twentieth century. In part I suspect it's a way of demonstrating beyond question that they know exactly what they're doing, that what they normally write isn't just a bunch of random noise, no matter what you yahoos think.

Revivals as a way of getting into the essence of a style

You can revive the musical style, but the clothes just never work

Revivals often allow an artist an interesting perspective. Looking back, they can see more clearly the quiddity of a style, what makes it what it is, than practitioners at the time possibly could. In addition, there is no idiosyncratic patron, perhaps one who is an enthusiastic amateur performer on the flute or bassoon, breathing down their neck. Sometimes it is an homage in the form of habitation, of getting inside the mind of an admired predecessor. And sometimes it is just fun dance music, more an exercise in creative orchestration than anything else.

Hence works like Prokofiev's First Symphony, "the Classical Symphony", and Tchaikovsky's Fourth Orchestral Suite, "Mozartiana".

Cute and sometimes moving

I actually like a lot of this kind of work, and used to pick it up on used LPs. Much of the lighter side of it comes out in ballet suites based on Baroque composers, such as Thommasini's "The Good-Humored Ladies" (after Scarlatti) and Walton's "The Wise Virgins" (after Bach). and Beecham's "Love in Bath" (after Handel). Very light, but a great pleasure.

Also in the dance vein are a couple of Richard Strauss suites: "Divertimento" and "Dance Suite" (both after Couperin).

More melancholy and moving is a piece by the less-known Alfred Schnittke. of partly Volga German ancestry, who lived during the Soviet period. Suite in the Old Style is lovely. It is not in imitation of anyone in particular, just Baroque in general, and in fact is a reworking of various film work that he did, including for an animated children's film. There are many arrangements, some for chamber orchestra, some for cello and piano, but I favor the violin and piano version at the link. I particularly like the Vadim Guzman performance, but it does not seem to be available on YouTube.

Are there any stylistic revivals that you find particularly interesting?

Mine are mostly Moderns doing Baroque. Are there other combinations I should check out?

September 26, 2019

Audiobooks, nationalities, and accents

Like many people, I listen to a lot of audiobooks. I tend not to like listening to fiction, partly because I can get tired of a book, but want to check other things out about it. Sometimes a book has interleaved sections at two different times or two different points of view, and only one of them is interesting. So I want to be able to skip and skim. Fellow writer, I apologize, but you sometimes write just...a...bit...too...much.

An example is the much-praised Water for Elephants, by Sarah Gruen. The present of the story takes place in a retirement home, where the embittered older character remembers his adventures in the circus during the Depression. The circus sections were pretty good, but the retirement home sections were insanely boring, much like many retirement homes. Since I couldn't just skip them, I gave up on the book, potentially losing whatever there was about it that people really liked.

Narrative nonfiction is the way to goSo I generally go for narrative nonfiction. Michael Lewis and Sarah Vowell books are both great listens. Vowell reads her own, and also gets various performing friends to do the voices and even compose songs for the audio versions.

I've also recently listened to David Wootton's book about the Scientific Revolution, The Invention of Science. Andrew Jackson O'Shaughnessy's account of the British leadership during the American Revolutionary War, The Men Who Lost America, and Sharon Bertsch McGrayne's account of the history of Bayesian statistics. The Theory That Wouldn't Die, all worth a listen. If you don't think a book about Bayes' Theorem sounds interesting, then it probably won't be.

Do they need to do the police in different accents?

Do you think these guys are Germans?

The last two books I listened to were David Quammen's account of the science and the politics and personalities of horizontal gene transfer, The Tangled Tree, and Adam Zamoyski's history of elite paranoia between the Napoleonic Wars and the Revolutions of 1848, Phantom Terror.

Both are excellent books, but the readers of both indulge in something I find extremely irritating: when directly quoted, people who were born in various countries all speak in the stereotyped accents of their nationalities. French, German, and Russian are the most common.

This, despite the fact that much of what is being quoted was written down, or spoken in their own language, or, if not their own, then a language other than English. Most people don't write with an accent. If they are non-native speakers writing in English, their word choices and syntax might reveal that, but that will be in the original, with no need for the reader to add anything.

It doesn't help that one of the readers manages to mangle Russian names and terms even while affecting to talk like a Russian. For what it's worth, I think the French words and names are better.

And what do they think this is adding? A good reader certainly creates voices for various characters. but a stereotyped national accent is scarcely the best way to do that. It makes the whole thing sound like one of those national-stereotype-filled movies from the 1960s set just before the First World War, like Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines or The Assassination Bureau. Sacre Bleu (which The Simpsons once helpfully subtitled as "Sacred Color Blue")!

I wouldn't have remarked on the accent thing, but it was two books in a row, and, unlike subtitles in a movie, I can't turn it off.

###What do you think about the use of accents in audiobooks?###

Or do you think I'm just too sensitive?

September 24, 2019

The protective force of cliche

Trees with departing leaves or birds are a common metaphorical image for dementia

My mother recently suffered a minor stroke. Combine with what seems to have been several prior, undetected strokes, she has gone from mild to fairly significant dementia. My sister and I were talking about her recently, and she listed a bunch of cliche phrases that my mother used, like "One day at a time", "time marches on", "so far so good", etc. You can lose a lot of vocabulary and mental capacity and still keep stock phrases.

In "Circles", one of the short sections that makes up the wonderful A Primer for Forgetting, Getting Past the Past, Lewis Hyde remembers his mother's failing intellect. She says a phrase to her husband over and over.

"You're going in circles," Father says. They say the CAT scan showed some atrophy of her frontal lobes, but the old material is still there. She is very much her old self. Her verbal tics and defenses remain. "Well, now Mrs. Pettibone," she says to herself, staring into the refrigerator before dinner. "We'll cope." "We'll get along" She is the shell of her old self, calcified language and no organism alive enough to lay down new layers.

Would it be possible to live in such a way as to never acquire habits of mind? When my short-term memory goes, I don't want to be penned up in the wickerwork of my rote responses. If I start being my old self, no heroic measures, please.

My brother was just over at my mom's. When he brought some boxes in from the storage area, she looked at them said that she is empty box with nothing inside.

Sometimes, behind the wickerwork, you can see eyes peering out.

September 19, 2019

How the 19th century Austrian secret service proved that people will give up private information if you save them time and money

The period between the Congress of Vienna in 1815 and the wave of "revolutions" in 1848 was one of repression, police action, and poorly organized, chaotic attempts at revolution that were quickly suppressed, with the exception of a few changes of government in France. That last year, 1848, was marked by much larger but still poorly organized and chaotic attempts at revolution, that resulted in retrenchment, and the replacement of the moderate monarchy of Louis-Phillipe with the less moderate if possibly more colorful Second Empire of Louis-Napoleon (there is no burden the people find more onerous than that of having to make choices).

Not that the repressive post-Napoleonic regimes were much more impressive than the attempts at revolt against them. According the Adam Zamoyski in Phantom Terror: Political Paranoia and the Creation of the Modern State, 1789-1848 (I listened to the audio), every leader from Metternich and Tsar Nicholas I on down spent their time obsessing over large-scale conspiracies of Masons, French revolutionaries, and Illuminati that did not exist, without recognizing that the various civil disturbances that they had to keep dealing with were really a response to the hopes of liberation and national autonomy that had been raised by the events of the quarter century after the French Revolution, and then dashed.

And it is kind of weird to think that the period from the Fall of the Bastille to the exile of Napoleon Bonaparte to St. Helena is only 25 years long. In his superb podcast The History of the Twentieth Century, Mark Painter calls the Congress of Vienna "an attempt to hit Ctrl + Z on the French Revolution" (this is based on memory, and may not be word-for-word accurate). Unlike a typo, it kind of stuck around.

But, still, the state apparatus of control put in place over that period worked pretty well at keeping the regimes in place until after an entire century they were all dumb enough simultaneously to start a gigantic war that none of them could win, and all of the multinational empires came apart like tissue paper you left in your back pocket when you threw your jeans in the washing machine.

The inescapable attraction of cheap and fast

In addition to his diplomatic skill, Metternich had quite the reputation as a lover. He is around 60 in this portrait.

Intelligence, opening people's mail, breaking codes, and other familiar practices grew through this period, though they look fairly amateurish from the point of view of intel operations over the twentieth century and into our time. Much of the letter reading seemed mostly to provide princes and leaders with salacious material about colleagues and rivals for personal entertainment.

Prince Klemens von Metternich was the dominant figure in Austria, and he wanted to make sure he could read everyone's mail. How he managed this is entertaining, and instructive.

According to Zamoyski, in the early part of the period, during the 1820s:

Metternich...identified control of the postal service as a key element in the invigilation of Europe. In the course of the eighteenth century Vienna had, by providing the most efficient postal service throughout the Holy Roman Empire, gained access to the correspondence passing through central Europe. Although the Empire had been abolished, much of the post carried around its former territory still passed through Austrian sorting offices. Metternich managed to extend this to Switzerland, a natural crossroads as well as a meeting place for subversives of every sort. All Swiss post passed through Berne, whose postal service was in the hands of the conservative patrician de Fischer family, with the result that all mail between France, Germany, and Italy was accessible to the Austrian authorities. Most of the mail going in and out of Italy passed through Lombardy, where it came under Austrian police scrutiny.

Metternich attempted to extend this to the rest of Italy, but failed, due to Papal opposition. Incidentally,"invigilation" seems to now be used only for proctoring exams, but it should probably be revived in the Zamoyski's wider sense.

Later on, in the 1840s, Metternich had to work a bit harder:

To ensure that as much European mail as possible continued to pass through Austrian domains, Metternich saw to it that the Habsburg postal service was cheaper and faster than the alternatives.

This apparently put a huge strain on the intelligence operatives, who had to open, copy, reseal, and return mail of interest to the post office without incurring additional delay. Zamoyski has some fun with how overworked this small set of bureaucrats was.

People knew there was a good chance their letters were being read, and tried various subterfuges to make it harder, but they still used the Austrian post, because it really was cheaper and faster than the alternatives.

While entertaining, the book is fairly narrow on the topic of government responses to subversion, and is not anything like a general history of the period. It may go into more detail on surveillance that some readers (or listeners) might like, but I found it extremely entertaining. Zamoyski knows how to feed in a lot of information without getting tedious, a rare skill among historians.

What privacy do you give up for cheap and fast?

I'm not even sure that's worth asking, because it's pretty much everything, for all of us. Metternich seems to have pioneered this form of big data gathering.

September 17, 2019

Winston Churchill, Andrew Roberts, and Brexit

Minister of Munitions WInston Churchill meets with women war workers in 1918

On the Econtalk podcast I listened to today, Russ Roberts interviewed Andrew Roberts on his recently published biography of Winston Churchill, Churchill: Walking with Destiny. Entertaining and informative, as always. Both Roberts and Roberts are big Churchill partisans, which makes sense, particularly in our glum era where history classes, seldom taught well to begin with, seem dedicated to eliminating any sign that any individual human being ever actually accomplished anything specific. Churchill was never anything other than specific, and he achieved a tremendous amount, making a great number of dramatic mistakes in the process.

I suppose that part of my issue with modern teaching of history is that it can't face the fact that mistakes, even vast, grotesque mistakes, are inevitable when people are acting without foreknowledge of the future. In a very real sense, to act is to screw up, and to act on a large, ambitious scale is to screw up on a large, ambitious scale.

The confounding appearance of BrexitBut in the course of this Andrew reveals himself to be a Brexiteer. I couldn't tell whether Russ was surprised or not. Andrew's position was that Brexit means that the UK can orient itself to the world, not just to Europe. Not that the UK will ever again be a world power. But it will be part of the world.

I can buy that, just as I can buy common-sense objections to the fact that Europe's main industry seems to be the creation of ever more precise, over-defined, and intrusive regulations. I once pointed out that while most places generate comedies of manner, New England's preferred form is the comedy of ethics. If that's true, then modern Europe should be generating comedies of regulation.

What Kurt Gödel has to do with extramarital sexWell, perhaps that is what Michel Houellebecq writes. He certainly has to write in a country where, as we all learned a couple of days ago, an employee traveling on business who dies during extramarital sex has suffered an industrial accident, making the company liable. It's easy to make fun of this stuff, of course. But if Kurt Gödel demonstrated that no matter what system of rules and axioms you use, there will always be true statements that are unprovable within that system. then any consistent system of regulations will inevitably produce a ridiculous result if interpreted strictly.

If this blog post had fixed margins, they would be too narrow for me to prove this theorem.

A regulator's favorite book of the Bible is LeviticusOK, I can't prove this either. But it is definitely the book that most closely approximates the ideal of a modern history curriculum: not events, not personalities, but the ritual practices you must perform, in exactly the way you must perform them.

Portrayals of ChurchillAndrew likes the movie Darkest Hour, with Gary Oldman, abhorring, as everyone should, the scene in the tube, which he describes as a focus group. Churchill led what people thought, he did not follow. And, he says, Churchill was on the Tube only once, in 1926, and never tried it again.

He also likes Robert Hardy's portrayal in the early 80s series, Winston Churchill: The Wilderness Years, a judgment with which I heartily concur. That was destination television for me and my roommates John and Pam that year.

Do you have a favorite biography of Winston Churchill?Mine is the two volumes of The Last Lion, by William Manchester, Visions of Glory, 1874-1932 and Alone, 1932-1940. Unfortunately, Manchester died before finishing the third volume, and it was finished by someone else, to all accounts not even coming close to the quality of the first two.

June 18, 2019

Essential but not urgent

There are fashions in words and expressions, as there are in hemlines, colors, and cocktails.

I like reading book reviews, even as I know I will never read most of these books. Particularly novels. I don't read many novels. And I certainly won't read most of the ones I read reviews of. I've gotten fussy in my old age, and most books are too earnest, too au courant, and too badly written to appeal to me.

Useful but misused

Which is why I am starting to feel that I am being bludgeoned by two fashionable descriptive words in particular": "urgent" and "essential", most often combined with "voice", and that most usually in the form of "new voice". The "urgent" is usually applied to some softcore political screed, denouncing our current President and associated administrative developments.

Note, I am not using these particular words to make a judgment on the actual works at issue. The last thing a writer is responsible for is what hackneyed phrase an overworked book reviewer chooses to use to decorate a review. I just suspect that not all of them are either urgent or essential.

A few examplesTime described Lisa Halliday, the author of Asymmetry, as "an essential new voice in fiction", which is probably the paradigmatic formulation.

Goodreads describes Shana Youngdahl, author of As Many Nows as I Can Get, as "an urgent new voice in young adult fiction", also a popular formulation.

The Globe and Mail describes Salman Rushdie's The Golden House as "an urgent new novel". It deals with our current political situation, and so I will evade its blandishments.

An essential YA novel

An urgent new voice in American fiction

Roxane Gay, on the other hand, is responsible for Urgent, Unheard Stories, since that is actually the title of her own book, so less wiggle room there.

I don't read novels to be hectored, persuaded, woked, or converted. If they try to do this, I ask them to leave my limited time and attention alone. Sometimes I am cordial, sometimes I am not.

What overused review words have lately been annoying you?Or is it just that reviewers are diverging in their reading interests from the rest of the reading public?