Craig Pirrong's Blog, page 52

September 29, 2019

It’s Time to Go to the Mattresses to Take on The Blob

I’ve been in France and Switzerland for a week lecturing and teaching. And what a stupid week it was. Arguably the most stupid week of my life.

Not with my trip–that was great. What was cosmically stupid went on in the US during it.

It started with the Greta Thunberg circus at the UN. Sorry, but “for the children” was well past its sell-by date when Hillary wretched it up decades ago. It is putrid beyond belief now. Teenagers have no moral or intellectual authority to harangue and hector about things they cannot remotely comprehend. Greta and the other muppets are just that . . . puppets being manipulated by cynical, power-seeking adults.

But that was just the hors d’ouevres. The cosmic stupidity was the impeachment farce sparked by a “whistleblower.”

The entire affair screams setup. The Dossier, Part Deux: Whistleblower.

To begin with, the stampede to impeachment began, and was affirmed by Nancy Pelosi, based on news reports about a whistleblower complaint, rather than the complaint itself or primary sources documenting the events at issue. And this despite the fact that the administration promised that it would release both within days–and did.

But the rush to judgment wasn’t a bug: it was a feature. No waiting for the actual facts to come out. Verdict first! Trial after!

And the administration’s release of the transcript of the call that allegedly so shocked the whistleblower and his multiple as yet anonymous sources demonstrates exactly why: the transcript refutes many aspects of the pre-release news reports, and contains crucial details that the whistleblowing complaint left out.

They make you swear to tell the whole truth when you testify, because leaving out facts is as dishonest as telling outright lies: the news reports were clearly not the whole truth, and as such represented a vile lie. Given this, the impeachment train definitely had to leave the station before the facts came out.

The hypocrisy is also beyond belief, even by current DC standards. The first favor Trump asked Ukrainian president Zelensky for was help in investigating . . . wait for it . . . foreign interference (or more accurately, foreign assistance in American i.e., Democratic interference) in the 2016 election. (This is the part left out of the original news reports.)

You see, foreign interference with American democracy is the worst thing ever, and no stone must go unturned investigating it . . . except when American Democrats are involved in it. But you are a traitor for trying to bring that to light, especially with the assistance of foreigners.

Trump also asked Zelensky about a Ukrainian prosecutor whom Joe Biden bragged about using–what’s that term?–oh yeah, “a quid pro quo” (the withholding of American aid) to get fired. A prosecutor who was investigating Biden’s son.

But Trump supposedly went beyond the pale at even hinting at a quid pro quo with Zelensky.

And how dare you–or Trump–connect dots!, you traitors you! Never mind that many of the people denying a possible connection between Biden’s demand to have the prosecutor fired and the firing of the prosecutor want you to believe that because Carter Page was in Moscow Trump was on the take and had models peeing on him in a Moscow hotel room.

Like I say. The hypocrisy is beyond belief.

The whole Biden affair is appalling on its face. Biden’s son Hunter–an admitted crackhead who was canned from the Navy for being a crackhead–couldn’t get any job that required him to piss in a cup (which is nowadays most jobs other than those that require you to say “do you want fries with that?”), and has zero experience in energy or Ukraine, yet miraculously wound up with a $50K/month no work job advising a Ukrainian energy company. (There’s also the issue of the lifelong loser’s ability to play rainmaker in China.)

Silly me. I though we were supposed to be deeply, deeply concerned about the Emoluments Clause. Another one-way DC street, apparently.

Then we get to the issue of the fact that the whistleblower complaint was–by his/her admission–hearsay. Funny, given credible whistleblowing complaints are supposed to be based on first-hand knowledge.

Sorry. “Were supposed to be.” Sometime between the date of the call and the filing of the complaint, the rules were changed by “the intelligence community” (AKA The Blob) to permit second- and third-hand information to serve as the basis for these complaints.

When this lot is involved, there are no coincidences, comrade. The fix was in, from the inside.

Since the substance of the call did not support the initial hysteria, the ground has now shifted to “coverup” because the White House ordered the call (along with some earlier ones) to be stored on a highly classified code word access system.

The chutzpah meter pegs on that one. Presidential calls with foreign leaders are supposed to be confidential, and open discourse is possible only if all involved believe that confidence will be respected. But from virtually day one in the Trump administration, details of confidential calls were leaked–presumably by someone in The Blob.

So it makes sense for Trump to attempt to lock down his calls. The leaking of (false and misleadingly incomplete) details of a call under the guise of “whistleblowing” is proof positive of his suspicions, and justification of his precautions, for all the good it did. Where there’s a will to leak, there’s a way. But there’s no reason to make it easy.

And boil the argument down to its essence. Trump has abused power by attempting to prevent leaks that interfere with his ability to perform his duties as chief executive.

Obama is no doubt laughing his ass off now.

And The Blob is the real abuser of power. It has no authority to leak, and the audacity of claiming that attempts of the legitimate, elected authorities to curb its leaking are an abuse of power is something to behold.

Operation Dossier and Operation Mueller failed. But the Deep State is nothing if persistent. Operation Ukraine is yet another attempt to interfere in the US political process, and indeed in the US elections.

And to be honest, I get far more furious at Americans doing it than foreigners.

The panicky haste with which the Democrats are proceeding with impeachment speaks volumes. It betrays their belief that the array of lunatic buffoons and buffoonish lunatics that comprise the party’s presidential candidates would lose, and lose badly, in 2020. So they need to resort to extra-electoral mechanisms to destroy whom they do not believe they can defeat. And in this effort, they have the full support of arrogant and unaccountable apparatchiks up and down the bureaucracy of the federal government.

This is war to the knife.

It’s time to go to the mattresses, and to take on and take out the mob–The Blob–that is arrogating to itself powers far beyond those conferred on it by the law.

September 20, 2019

The Simple (and Very Old) Economics of the Stock Market Data Pricing Controversy

The most contentious battle in American securities markets right now is being waged over exchange pricing of data, in particular over proprietary order book feeds. The battle pits the exchanges against market users (e.g., HFT firms, institutional traders) with the latter claiming that the prices charged by the former border on the extortionate.

The critics actually have a very good point. The economics of the situation imply that the prices the competing exchanges charge are ABOVE the price a monopoly would charge.

No. Really.

So how could competing firms charge a supra-monopoly, let alone supra-competitive, price? The answer to this question is something pointed out by the first true mathematical economist, Augustin Cournot, in his Principes Mathematique, published in 1838. In that book, Cournot laid out “the problem of complements.” Cournot showed that imperfectly competitive firms overprice complementary goods. (Cournot’s example involved zinc and copper in the production of brass. They are complements used in fixed proportion.)

The basic issue is that when goods are complements, if firm A raises its price firm B that produces a complement to A’s good cannot steal sales from A by cutting its price (as would be the case of A’s and B’s goods were substitutes). This reduces the incentive to cut price, and actually provides an incentive to increase prices in order to get a bigger piece of the surplus that is generated when the consumer buys both goods.

This situation fits the stock market case perfectly. Execution services on US exchanges (e.g., NYSE, BATS) are substitutes, but data services are complements.

Consider an HFT firm. One source of profits for this firm is to exploit price discrepancies across exchanges. This requires having near immediate and simultaneous access to prices across all exchanges. Or consider a buyside firm that is trying to minimize execution costs by a clever order routing strategy. Optimizing the allocation of orders across exchanges requires knowing the order book on all the exchanges.

In other words, there are many market participants who have to collect the entire set (of exchange data). This makes the data provided by competing exchanges complements, which by the Cournot logic, forces prices above the competitive level, and indeed, above the monopoly level.

Furthermore, the problem becomes worse, the larger number of exchanges. This is a situation in which lower concentration leads to less competitive outcomes. (Robin Hansen made a similar point recently.)

This is yet another example of the only law that is never repealed: the law of unintended consequences. The intent of RegNMS was to increase competition in the execution of stock trades, and it has done a marvelous job of that. However, the unintended effect of this “fragmentation” (i.e., the increase in the number of execution venues and decline in concentration across exchanges) has been to create and exacerbate a complements problem in data.

A couple of final points. Perhaps one could make a second-best argument here: low execution fees and high data fees may be a good way of covering the fixed costs of operating exchanges (a la Ramsey pricing). Perhaps, but unproven.

What is the right regulatory response? Not clear. I addressed similar conundrums in my 2002 Market Macrostructure article. Natural monopoly-style/pricing regulation could mitigate the overpricing problem, but entails its own costs (e.g., undermining incentives to innovate). The issue is particularly challenging here because efficiency-enhancing competition on one dimension (execution) leads to inefficient problems-of-complements competition on another (data).

As I argued in Market Macrostructure, it really comes down to an issue of property rights. Should exchanges have exclusive ownership of their data? Should this ownership be attenuated in some way, such as limitation on prices, or a required pooling of data that would be sold by a monopolist, with revenues shared by the exchanges? Here is a case where a monopoly would actually improve outcomes.

Maybe that is the way to split the baby, politically. Exchanges would get rents, but efficiency would be improved. Not a first-best solution, but maybe a second best one, and one that could represent a Coasean bargain between exchanges and their customers. And perhaps the regulator–the SEC–could help facilitate and coordinate that deal.

Back to the Fed Future, or You Had One Job

In the Gilded Age, American financial crises (“panics,” in the lexicon of the day) tended to occur in the fall. Agriculture played a predominant role in the economy, and marketing of the new crop in the fall led to a spike in the demand for cash and credit. In that era, however, the supply of cash and credit was not particularly elastic, and these demand spikes sometimes turned into panics when supply did not (or could not) respond accordingly.

The entire point of the Fed, which was created in the aftermath of one of these fall panics (the Panic of 1907, which occurred in October), was to make currency supply more elastic and thereby reduce the potential for panics. In essence, the Fed had one job: lender of last resort to ensure a match of supply and demand for currency/credit, when the latter was quite volatile.

This week’s repospasm is redolent of those bygone days. Now, the spikes in demand for liquidity are not driven by the crop cycle, but by the tax and corporate reporting cycles. But they recur, and several have occurred in the autumn, or on the cusp thereof (this being the last week of summer).

One of my mantras in teaching about commodities is that spreads price bottlenecks. Bottlenecks can occur in the financial markets too. The periodic spikes in repo rates–not just this week, but in December, and March–relative to other short term rates scream “bottleneck.” Many candidates have been offered, but regardless of the ultimate source of the clog in the plumbing, the evidence from the repo market is that there are indeed clogs, and they recur periodically.

The Fed’s rather belated and stumbling response suggests that it is not fully prepared to respond to these bottlenecks, despite the fact that their regularity suggests that the clogs are chronic. As the saying goes, “you had one job . . . ” and the Fed fell down on this one.

And maybe the problem is that the Fed no longer just has one job, and it has shunted the job that was the reason for its creation to the back of the priority list. Nowadays, the Fed has statutory obligations to control employment and inflation, and views its main job as managing aggregate demand, rather than tending to the financial system’s plumbing.

This is concerning, as dislocations in short-term funding markets can destabilize the system. These markets are systemically important, and failure to ensure their smooth operation can result in crises–panics–that undermine the ability of the Fed to perform its prioritized macroeconomic management task.

One of the salutary developments post-crisis has been the reduced reliance of banks and investment banks on flighty short-term funding. The repo markets are far smaller than they were pre-2008, and the unsecured interbank market has all but disappeared (representing only about .3 percent of bank assets, as compared to around 6 percent in 2006). But this is not to say that these markets are unimportant, or that bottlenecks in these markets cannot have systemic consequences. For the want of a nail . . . .

Moreover, the post-crisis restructuring of the financial system and financial regulation has created new potential sources of liquidity shocks, namely a supersizing of potential demands for liquidity to pay variation margin. When you have a market shock (e.g., the oil price shock) occurring simultaneously with the other sources of increased demand for liquidity, the bottlenecks can have very perverse consequences. We should be thankful that the shock wasn’t a Big One, like October, 1987.

Hopefully this week’s tumult will rejuvenate the Fed’s focus on mitigating bottlenecks in funding markets. Maybe the Fed doesn’t have just one job now, but this is an important job and is one that it should be able to do in a fairly routine fashion. After all, that job is what it was created to perform. So perform it.

September 17, 2019

Fentanyl: The Real Trade War

The Sino-American “trade war” narrative is one of the most idiotic ones in recent memory, and given that it has to compete with things like “Russian collusion” that’s saying a lot. This narrative is appealing to superficial, lazy journalists, is tailor made for governments and companies looking to excuse poor results, and fits right in with the relentless anti-Trump media drumbeat.

Trade is just one weapon in a deeper geopolitical/geostrategic contest between the United States and China. This contest pits an established status quo power with an emergent, revanchist, revisionist one. These powers have fundamentally different visions for the operation of the global system.

The struggle is being waged in myriad dimensions, and often in a quite asymmetric way. One of China’s most deadly–literally–asymmetric weapons is fentanyl. And anyone who thinks that China’s shipping of massive quantities of this extremely dangerous drug to the US is not an intentional asymmetric warfare tactic is delusional.

Funding Market Tremors: Today May Not Have Been “The Big One,” But It Was Bad Enough

The primary reason for my deep skepticism about the wisdom of clearing

mandates was liquidity risk. As I said repeatedly, in order to reduce

counterparty risk, clearing necessarily increased liquidity risk through the

variation margining mechanism. Further, it was–and is–my opinion that

liquidity risk is a far graver systemic concern that counterparty risk.

A major liquidity event has occurred in the last couple of days: rates

in the repurchase market–the major source of short term funding for vast

amounts of trading activity–shot up to levels (around 5 percent) nearly double

the Fed’s target ceiling for that rate. Some trades took place at far

higher rates than that (e.g., 9.25 percent).

Market participants have advanced several explanations, including big cash

demands due to corporate tax payments coming due. Izabella Kaminska at

FTAlphavile offered this provocative alternative, which resonates with my

clearing story: the

large price movements in oil and fixed income markets in the aftermath of the

attack on the Saudi resulted in large margin calls in futures and cleared OTC

markets that increased stresses on the funding markets.

To which one might say: I sure as hell hope that’s not it, because although there was a lot of price action yesterday, it wasn’t The Big One. (The fact that Fred Sanford’s palpitations occurred because he couldn’t get his hands on cash makes that bit particularly apropos!)

I did some quick back-of-the-envelope calculations. WTI and Brent variation

margin flows (futures and options) were on the order of $35 billion. Treasuries

on CME maybe $10 billion. S&P futures, about $1 billion. About $2 billion

on Eurodollar futures.

The Eurodollar numbers can help give a rough idea of margin flows on cleared

interest rate swaps. Eurodollar futures open interest is about $12 trillion.

Cleared OTC notional volume (not just USD, but all IRS) is around $80 trillion.

But $1mm in notional of a 5 year swap is equivalent to 20 Eurodollar futures

with notional amount of $20 trillion. So, as a rough estimate, variation margin

flows in the cleared IRS market are on the order of 100x for Eurodollars. That

represents a non-trivial $200 billion.

Yes, there are potentials for offsets, so these numbers are not additive.

For example, a firm might have offsetting positions in EDF and cleared IRS. Or be

short oil and long Treasuries. But variation margin flows on the order of $300

billion are not unrealistic. And since market moves were relatively large

yesterday, that represents an increment over the typical day.

So we are talking real money, which could certainly contribute to an

increased demand for liquidity. But again, yesterday was not remotely a truly

epic day that one could readily imagine happening.

A couple of points deserve emphasis. The first is that perhaps it was coincidence or bad luck, but the big variation margin flows coincided with other sources of increased demand for liquidity. But hey, stuff happens, and sometimes stuff happens all at once. The system has to be able to withstand such simultaneous stuff.

The second is related, and very concerning. The spikes in rates observed

periodically in the repo market (not just here, but notoriously in China)

suggest that this market can go non-linear. Thus, even if the increased funding

needs caused by the post Abqaiq fallout wasn’t The Big One, in a non-linear

market, even modest increases in funding needs can have huge impacts on funding

costs.

This highlights another concern: inter-market feedback. A shock in one

market (e.g., crude) puts stress on the funding market that leads to spikes in

repo rates. But these spikes can feedback into prices in other markets. For

example, if the inability to fund positions causes fire sales that cause big

price moves that cause big variation margin flows which put further stress on

the funding markets.

Yeah. This is what I was talking about.

Today’s events nicely illustrate another concern I raised years ago.

Clearing/margining make markets more tightly coupled: the need to meet margin

calls within hours increases the potential stress on the funding markets. As I

tell my classes, unlike in the pre-Frankendodd days, there is no “fuck

you” option when your counterparty calls for margin. You don’t pay, you

are in default.

This tight coupling makes the market more vulnerable to operational

failings. On Black Monday, 1987, for example, the FedWire went down a couple of

times and this contributed to the chaos and the potential for catastrophic

failure.

And guess what? There was a (Fed-related!) operational problem today. The NY

Fed announced that it would hold a repo operation to supply $75 billion of

liquidity . . . then

had to cancel it due to “technical difficulties.”

I hate it when that happens! But that’s exactly the point: It happens. And

the corollary is: when it happens, it happens at the worst time.

The WSJ article also contains other sobering information. Specifically,

post-crisis regulatory “reforms” have made the funding markets more

rigid/less-flexible and supple. This would tend to exacerbate non-linearities

in the market.

We’re from the government and we’re here to help you! The law of unintended

(but predictable) consequences strikes again.

Hopefully things will normalize quickly. But the events of the last two days

should be a serious wake-up call. The funding markets going non-linear is the

biggest systemic risk. By far. And to the extent that regulatory changes–such

as mandated clearing–have increased the potential for demand surges in those

markets, and have reduced the ability of those markets to respond to those

surges, in their attempt to reduce systemic risks, they have increased them.

I have often been asked what would cause the next financial crisis. My

answer has always been: the regulations intended to prevent a recurrence of the

last one. Today may be a case in point.

September 16, 2019

Beta O’Rourke Fails Texas History–and Texas

Democratic presidential candidate Robert Francis “Beto” (AKA “Beta”) O’Rourke, currently running neck-and-neck with Rounding Error, is attempting to jumpstart his floundering campaign with strident threats to confiscate “assault weapons”:

“Hell, yes, we’re going to take your AR-15,” the former Texas congressman shouted, to cheers from the audience. “We’re not going to allow it to be used against our fellow Americans anymore.”

This prompted Texas state representative Briscoe Cain to tweet: “My AR is ready for you Robert Francis.”

Beta then proceeded to go all drama queen, replying on Twitter: “This is a death threat, Representative. Clearly, you shouldn’t own an AR-15—and neither should anyone else.”

Going even drama queenier, Beta reported Cain to the FBI.

FFS. So what’s next? Will Beta demand the digging up and ritual burning of Charlton Heston’s corpse? (Actually kind of amazed YouTube/Google hasn’t consigned that to its memory hole.)

Beta, who is from Texas, apparently needs a Texas history lesson. Cain’s sentiment has a long tradition in Texas, dating from the dawn of the Republic in 1835, in fact.

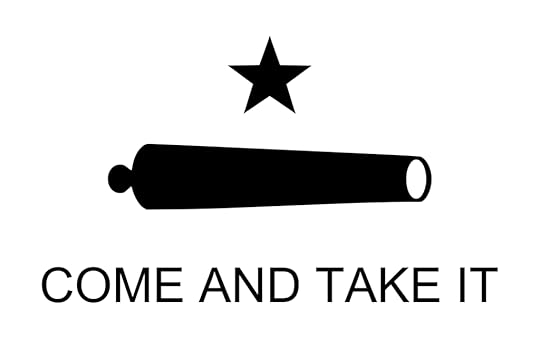

The story is this. In 1831, the Mexican government gave the Anglo “Texian” citizens of Gonzales a small cannon for use in defense against marauding Comanches. When the Texians became restive a few years later, and began to resist the Mexican government, the Mexicans thought better of their gift and sent a detachment of 100 men under a Lieutenant Francisco de Castañeda to retrieve it. Men from Gonzales and other towns rallied, and told Castañeda to bugger off. They emphasized their message with a homemade flag depicting the image of a cannon, with the words “Come and Take It” emblazoned on it.

After some fitful skirmishing, Castañeda decided he’d rather not, actually, and so he scooted off, leaving the cannon in the Texians’ hands.

Castañeda was not only present at the very beginning of the Texas Revolution in Gonzales: he was present at the end, surrendering the Alamo to Juan Seguin on 4 June, 1836. Two time loser. Id, puta!

State Rep. Cain was therefore echoing a proud Texas tradition, and O’Rourke, who affects some Mexican connection with his faux nickname (why isn’t that considered cultural appropriation?) (maybe his ancestors served in the San Patricio Battalion!) is the one playing the role of the threat to the liberties and right of self-defense of Texans–and Americans generally.

So as someone who got to Texas as soon as I could, I say to Beta: Come And Take It. And that is your history lesson for today.

September 15, 2019

The Attack on Abqaiq: Iran Burns Its Boats

There is an apocryphal story about Moshe Dayan, in which when asked what was the secret of his success, he answered “fighting Arabs.” True or not, there is a certain veracity to the judgment. It’s not for no reason that there are articles with titles like “Why Arabs Lose Wars” and books with titles like “Armies of Sand: The Past, Present, and Future of Arab Military Effectiveness.” Yes, there have been exceptions, like the Jordanian Legion, but for the most part when Arab armies fight non-Arabs, the former get by far the worst of it.

The Saudi armed forces are arguably the worst of the lot, despite the billions in advanced arms that have been lavished on them over the years. It is a force designed primarily for regime protection, or more accurately, designed so that it does not pose a threat to the regime. Fighting the KSA’s external enemies is a secondary–or tertiary–consideration. In their minds, that’s what they pay the US for.

The appalling performance of the Saudi army in wars in Yemen, whether it be decades ago or today, provides ample testimony to this rather harsh judgment.

With this sorry history in mind, I consider it highly likely that Saudi military ineptitude contributed to, and was arguably the primary cause of, the devastating attack on the Abqaiq oil processing plant. This has resulted in the disabling, for an indeterminate period, of 50 percent of Saudi oil production.

Especially in light of past Houthi (and Shiite Iraqi militia) attacks on Saudi facilities, this was an obvious target. For it to be hit so effectively, with not even the Saudis claiming to have downed any of the attacking aircraft (drones? rockets? missiles?) is a military failure of the first order.

So what now? The US has come out and directly blamed Iran. Whether Iran used one of its myriad cutouts, or pushed the button itself, is immaterial. It is almost certain that it is responsible.

So how to respond?

Even by Trump’s standards, his initial tweet in response was cringeworthy:

It’s one thing to await information from the KSA, and to coordinate with them. It’s quite another to delegate–as Trump appears to do–the decision on the American response to the militarily inept oil ticks that rule Saudi Arabia who are not our friends.

Trump has shown forebearance with Iran before. But shooting down a drone (albeit an expensive one) and attacking what is arguably the singlemost important oil installation in the world are on totally different levels. And Trump no doubt is thinking “if this is what forebearance gets me, screw it.”

Ironically, moreover, this occurred after Trump unceremoniously defenestrated the most conspicuous Iran hawk in his administration, and made noises about negotiating with Iran, and backing the French credit line initiative.

Want to bet that John Bolton is laughing his ass off now?

And what say you, Emmanuel Macron and Angela Merkel?

Iran’s escalation at a time of American efforts to defuse tensions is akin to burning its boats. It makes clear that negotiation is off the table. It is either capitulation by the US (and Europe, as if it counts) or conflict. And how the US responds to this extremely provocative act is not something that should be left to the House of Saud.

September 14, 2019

Bakkt in the (Crypto) Saddle

ICE is on the verge of launching Bitcoin futures. The official start date is 23 September.

The ICE contract is distinctive in a couple of ways.

First, it is a delivery settled contract. Indeed, this feature is what made the ICE product so long in coming. The exchange had to set up a depository, the Bakkt Warehouse. This required careful infrastructure design and jumping through regulatory hoops to establish the Bakkt Trust Company, and get approval from the NY Department of Financial Services.

Second, the structure of the contracts offered is similar to that of the London Metal Exchange. There are daily contracts extending 70 days into the future, as well as more conventional monthly contracts. (LME offers daily contracts going out three months, then 3-, 15-, and 27-month contracts). The daily contracts settle two days after expiration, again similar to LME.

The whole initiative is quite fascinating, as it represents a dual competitive strategy: Bakkt is simultaneously competing in the futures space (against CME in particular), and against spot crypto exchanges.

What are its prospects? I would have to say that Bakkt is a better mousetrap.

It certainly offers many advantages as a spot platform over the plethora of existing Bitcoin/crypto exchanges. These advantages include ICE’s reputation, the creation of a warehouse with substantial capital backing, and regulatory protections. Here is a case in which regulation can be a feature, not a bug.

Furthermore, for decades–over a quarter-century, in fact–I have argued that physical delivery is a far superior mechanism for price discovery and ensuring convergence than cash settlement. The myriad issues that were uncovered in natural gas when rocks were overturned in the post-Enron era, the chronic controversies over Platts windows, and the IBORs have demonstrated the frailty, and vulnerability to manipulation of cash settlement mechanisms.

Crypto is somewhat different–or at least, has the potential to be–because the CME’s cash settlement mechanism is based off prices determined on several BTC exchanges, in much the same way as the S&P500 settlement mechanism is based on prices determined at centralized auction markets.

But the crypto exchanges are not the NYSE or Nasdaq. They are a rather dodgy lot, and there is some evidence of manipulation and inflated volumes on these exchanges.

It’s also something of a puzzle that so many crypto exchanges survive. The centripetal forces of liquidity tend to cause trading in a particular instrument to gravitate to a single platform. The fact that this hasn’t happened in crypto is anomalous, and suggests that normal economic forces are not operating in this market. This raises some concerns.

Bakkt potentially represents a double-barrel threat to CME. Not only is it competing in futures, if it attracts a considerable amount of spot trading activity (due to a superior trading, clearing, settlement and custodial platform, reputational capital, and regulatory safeguards) this will undermine the reliability of CME’s cash settlement mechanism by attracting volume away from the markets CME uses to determine final settlement prices. This could make these market prices less reliable, and more subject to manipulation. Indeed, some–and maybe all–of these exchanges could disappear if ICE’s cash market dominates. CME would be up a creek then.

That said, one of the lessons of inter-exchange competition is that the best mousetrap doesn’t always win. In particular, CME has already established liquidity in the futures market, and as even as formidable competitor as Eurex found out in Treasuries in the early-oughties, it is difficult to induce a shift of liquidity to a competitor.

There are differences between crypto and other more traditional financial products (cash and derivatives) that may make that liquidity-based first mover advantage less decisive. For one thing, as I noted earlier, heretofore cash crypto has proved an exception to the winner-takes-all rule. Maybe the same will hold true for crypto futures: since I don’t understand why cash has been an exception to the rule, I’d be reluctant to say that futures won’t be (although CBOE’s exit suggests it might). For another, the complementarity between cash and futures in this case (which ICE is cleverly exploiting in its LME-like contract structure) could prove decisive. If ICE can get traction in the fragmented cash market, that would bode well for its prospects in futures.

Entry into a derivatives or cash market in competition with an incumbent is always a highly leveraged bet. Odds are that you fail, but if you win it can prove enormously lucrative. That’s essentially the bet that ICE is taking in BTC.

The ICE/Bakkt initiative will prove to be a fascinating case study in inter-exchange competition. Crypto is sufficiently distinctive, and the double-barrel ICE initiative sufficiently innovative, that the traditional betting form (go with the incumbent) could well fail. I will watch with interest.

September 3, 2019

Rogozin the Ridiculous: Like a Bad Kopec, He Keeps Turning Up

A few months ago long-time commenter Ex-Global Super-Regulator on Lunch Break inquired of the whereabouts of one of my favorite whipping boys, Rogozin the Ridiculous. Well, he’s reappeared! And not in a good light! (I’m sure you are all shocked, shocked!)

Apparently RtR was playing the typical role of a dog fighting under the carpet, but the battle has become public. Rogozin’s replacement as Deputy Prime Minister (Rogonotcop having moved to head Roscosmos) came out blasting his predecessor for massive corruption and mismanagement in the construction of the Vostochny Cosmodrome, something I wrote about when the stores about this first appeared:

A series of corruption scandals, cost overruns and mishaps at Russia’s new Vostochny Cosmodrome have brought long-simmering questions about the leadership of the country’s space agency into public view.

“The situation is unacceptable for everyone, including the construction of the first stage and the second stage” of the space center, Deputy Prime Minister Yury Borisov told Vedomosti newspaper in an interview published Monday, adding that the Defense Ministry may take over part of the work.

Rogo’s response? Basically “eta Rossiya”: “It’s always been this way: some build, while others criticize. It’s part of the business.”

Truth be told, Rogozin’s building left a lot to criticize: inspectors found a “critical defect” on a launchpad in November (two years after it became operational!). And of course the corruption was epic:

The Prosecutor General’s Office has opened a series of criminal cases after uncovering 10 billion rubles ($150 million) in losses during construction at Vostochny. In one sparkling example of corruption, a contractor accused of stealing 4 million rubles was detained in Minsk, Belarus, while driving a Mercedes covered in Swarovski crystals.

Corruption is apparently rife at Rogozin’s new gig:

Alexei Kudrin, the head of Russia’s Audit Chamber, told lawmakers last year that he had found 760 billion rubles ($11.4 billion) of financial violations in Roscosmos’s books, including several billion that had been “basically stolen,” describing the space agency as “the champion in terms of the scale of such violations.” Roscosmos said the criticism related to a 2017 audit, before Rogozin’s appointment.

I’m totally sure he clean that right up!

Rogozin is like a bad kopec: he always keeps turning up. So never fear, EX-Global Super-Regulator on Lunch Break, I’m sure I’ll have an opportunity to write about him again.

August 31, 2019

Americans’ Realistic Response to a Fight For Freedom in Hong Kong

Hong Kong has been convulsed by anti-government protests for weeks. Protestors have numbered in the hundreds of thousands, and are facing increasing violence from Chinese authorities. The atmosphere is heavy with fears of a fierce crackdown by Beijing, along the lines of Tiananmen Square, a little more than 30 years ago.

Hong Kong protestors are literally wrapping themselves in American flags (redolent of the replica of the Statue of Liberty in Tiananmen). Some are even donning MAGA hats and pleading for the US to come to their aid.

But Americans’ responses to all this are decidedly muted, and many appear to be paying little attention to the truly historic events in Hong Kong. This has led many to wonder why. Tyler Cowen hypothesizes that Americans are too obsessed with their own inter-tribal political wars to pay attention:

Sadly, the most likely hypothesis is that Americans and many others around the world simply do not care so much anymore about international struggles for liberty. It is no longer the 18th or 19th century, when one democratic revolution provided the impetus for another, and such struggles were self-consciously viewed in international terms (a tradition that was also adopted by communism). The 1960s, which saw the spread of left-wing movements around the world, embodied that spirit. So did the anti-Communist movements of the 1980s, such as Solidarity, which overcame apparently insuperable odds to help liberate Poland and indeed many other parts of Eastern Europe.

In contrast, I hear no talk today about how the Hong Kong protesters might inspire broader movements for liberty.

Instead, Americans are preoccupied with fighting each other over political correctness, gun violence, Trump and the Democratic candidates for president. To be sure, those issues deserve plenty of attention. But they are soaking up far too much emotional energy, distracting attention from the all-important struggles for liberty around the world.

It’s 2019, and the land of the American Revolution, a country whose presidents gave stirring speeches about liberty and freedom in Berlin during the Cold War, remains in a complacent slumber. It really is time to Make America Great Again — if only we could remember what that means.

With all due respect to Tyler, I think the answer is far different: Americans are far more realistic than he is.

This realism is the bitter fruit of the idealism of the post-Cold War world, and in particular, attempts to advance liberty around the world.

Let’s look at the record. And a dismal record it is.

Start with the collapse of the Soviet Union, which led to a burst of euphoria and a belief that this would cause liberty to spread to the lands behind the Iron Curtain. The result was far more gloomy.

There were a few successes. The Czech Republic, Poland, Hungary. Not coincidentally, the successes and quasi-successes occurred in places that had been part of the Catholic and Protestant west. Outside of that, the states of the FSU and other Warsaw Pact states lapsed back into authoritarianism, usually after a spasm of chaos. (Ukraine went from authoritarianism to chaos to authoritarianism and then to a rather corrupt semi-chaos.)

In particular, the bright hopes for Russia faded rapidly, and after a decade of chaotic kleptocracy that country has settled into nearly two decades of authoritarian kleptocracy. Moreover, Americans (and westerners generally) soon wore out their welcome, in part because of their condescension in dealing with a reeling and demoralized yet proud society, in part because of their complicity in corruption (and yes, I’m looking at you, Harvard), and in part because their advice is firmly associated in Russian minds with the calamity of the 1998 economic collapse. Yes, you can quibble over whether that blame is justified, but that’s irrelevant: it is a reality.

Countries where Color Revolutions occurred (e.g., Georgia) also spurred western and American optimism and support. But hopes were soon dashed as these countries too slipped back into the mire, rather than emerging as beacons of liberty.

I could go on, but you get the point.

Let’s move forward a decade, to Afghanistan and Iraq. In both places, there was another burst of euphoria after brutal regimes were toppled. Remember purple fingers? They were a thing, once, what seems a lifetime ago.

Again, hopes that freedom would bloom were soon dashed, and both countries descended into horrific violence that vast amounts of American treasure and manpower were barely able to subdue. And again, especially in Iraq, the liberators were soon widely hated.

The lesson of Iraq is particularly instructive. The overthrown government was based on a party organization with a cell structure that was able to organize a fierce and bloody resistance against the Americans and their allies. The attitudes of the population meant far less than the determination and bloody-mindedness of a few hard, ruthless men.

Let’s move forward another decade, to the Arab Spring. The best outcome is probably Egypt, which went from an authoritarian government rooted in the military to a militant Muslim Brotherhood government and back to military authoritarianism. In other words, the best was a return to the status quo ante. The road back was not a happy one, and the country would have been better without the post-Spring detour into Islamism.

Elsewhere? Humanitarian catastrophes, like Libya and Syria, that make Game of Thrones and Mad Max look like frolics. Enough said.

Given this litany of gloomy failures, who can blame Americans for extreme reluctance to engage mentally or emotionally with what is transpiring in Hong Kong? They are only being realistic in concluding it is unlikely to end well, and that the US has little power to engineer a happy ending.

And what is the US supposed to do, exactly? The country is already employing myriad non-military instruments of national power in a strategic contest with China. Again, the “trade war” is not a war about trade: trade is a weapon in a far broader contest.

Military means are obviously out of the question. And let’s say that, by some miracle, the Chinese Communist Party collapses, and the US military, government agencies, and NGOs did indeed attempt to help secure the country. How would that work out? Badly, I’m sure.

The country is less culturally intelligible to Americans than Russia, or even the Middle East, and not just because of the language barrier, but because of vastly different worldviews. China is physically immense and has the largest population in the world. Chinese are extraordinarily nationalist, and it is not hyperbole to say that the Han in particular are racial supremacists. Years of CCP propaganda have instilled a deep hostility towards the US in particular, and many (and arguably a large majority of) Chinese blame the west and latterly the US of inflicting centuries of humiliation on China. A collapsed CCP would not disappear: it would almost certainly call on its revolutionary tradition and launch a fierce and bloody resistance. People in Hong Kong may be flying American flags now, but I guarantee that in a post-Communist China, there would be tremendous animosity towards Americans.

When you can’t do anything, the best thing to do is nothing. Some of the greatest fiascos in history have been the result of demands to do something, when nothing constructive could be done.

The American diffidence that Tyler Cowen laments reflects an intuitive grasp of that, where the intuition was formed by bitter experience.

I despise the CCP. It is, without a doubt, the greatest threat to liberty in the world today. It is murderous, and led by thugs. I completely understand the desire of those with at least some comprehension of a different kind of government, and a different way of life, to be rid of it. I am deeply touched by their admiration for American freedom–something that has become increasingly rare, and increasingly besieged, in America itself.

But there ain’t a damn thing I, or even the entire US, can do to make that happen.

Ironically, I guarantee any American involvement in a putative post-CCP China would only contribute to internecine political warfare in the US.

The situation is analogous to that in 1946, when George Kennan wrote the Long Telegram. Confronting (prudently) and containing China is the only realistic policy. After years of delusional policies that mirror imaged China, the Trump administration is finally moving in that direction, and has achieved considerable success in creating a consensus around that policy (the deranged Democratic presidential candidates and those corrupted by Chinese money excepted, both of whom are siding with China at present, because Bad Orange Man and moolah).

But even there we have to be realistic. For even after containment achieved its strategic objective, and the USSR collapsed, it did not result in a new birth of liberty east of the Niemen and the Dneiper. Nor should we expect that to happen on the Yangtze or the Yellow if containment consigns the CCP to the dustbin of history.

Craig Pirrong's Blog

- Craig Pirrong's profile

- 2 followers