Craig Pirrong's Blog, page 46

March 22, 2020

If Policymakers are Going to Crater the World Economy, They Should At Least Make That Decision Based on Reliable Data

I’ve expressed considerable skepticism about relying on test data to craft COVID-19 (AKA CCPVID-19) policy responses. This note formalizes the basis for my skepticism. Testing data would provide an accurate measure of the prevalence of severe infection if (a) the tests had low rates of false positives and false negatives, and (b) testing was random. Neither condition is remotely correct. Meaning that the test-based statistics are an extremely poor guide for policymakers, and a particularly dubious basis for driving the world economy into a depression, at the cost of trillions of dollars.

So what should we look at? If this is a particularly prevalent, virulent, and deadly respiratory disease, it will result in elevated levels of hospital admissions or physician visits for respiratory illness, and elevated levels of death from respiratory causes. That’s what we should be looking at. Or more to the point, what policymakers should be looking at. Is this a particularly deadly and widespread disease? If it is, it will have measurable effects on mortality and hospital admissions.

The CDC does collect data on influenza. Unfortunately, many of the statistics condition on a positive influenza test. For example, hospital admissions with a positive influenza test. That is not helpful, because we are focused on something other than the influenzas the CDC tracks. But the CDC does report deaths from influenza and pneumonia. That is more useful, as a deadly new respiratory illness should lead to higher pneumonia death rates.

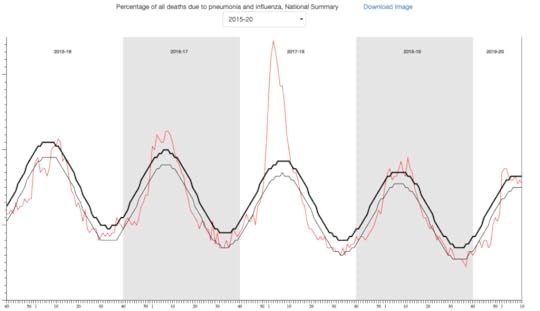

Through last week, these data demonstrate little elevation on a national or regional basis. There was a spike in deaths above the “threshold” level early in 2020 (where the threshold basically is at the 5 percent significance level above the seasonally adjusted baseline), but subsequently it converged almost back to the baseline:

It is particularly interesting to compare 2019-20 with 2017-18. Heretofore, 2019-20 compares very favorably to that year, and even to less extreme years 2016-17 and 2018-19. Through now, in other words, 2019-20 does not look at all unusual.

The CDC also tracks data on those seeking medical treatment for flu-like symptoms: these data do not require a positive influenza test, and thus should reflect people suffering flu-like symptoms caused by something other than the flu. These data show somewhat higher levels for 2019-20 compared to previous years (except for 2017-18, which was much higher), but not extremely so. The main worrying aspect to the 2019-20 data is that they do not appear to be declining as rapidly with the approach of spring as in prior years. But the data do not exhibit a huge spike–they are just declining less rapidly than in prior years.

Yes, these data are backwards looking. I can imagine scenarios, such as the late introduction of CCPVID-19 into the US, which would mean that the wave of deaths/illness would not be manifest in the data, as it is still to come. But there are indications that the virus has been on the loose in the US at least since mid-January, and given its existence in China no later than mid-November, it could have been present in the US prior to mid-January. If it is indeed highly contagious and deadly, it should be leaving tracks in the mortality data.

It would be highly informative to have such data for other countries. I am not aware of it in as accessible a form as is provided by the CDC. If anyone can point me to it, that would be greatly appreciated.

You might argue that I am whistling past the graveyard. All I can say is that the data that alarmists point to is highly unreliable (and inherently so), and the reliable data as of yet demonstrate nothing out of the ordinary on the dimension that really matters–people dying from respiratory ailments.

What I can say with considerable confidence is that policymaking is driven by flawed data, and that there are types of data that would be more informative, and which are not infected by (deliberate choice of words) the problems inherent in the flawed data that dominates public discourse, and apparently dominates public policymaking. Produce that data. Disseminate that data. Make sure policymakers are aware of it, and are aware of the deficiencies of the data we hear about 24/7.

March 19, 2020

Are We Destroying Society In Order to Save It?

In 1968, journalist Peter Arnett claimed that a U.S. major had told him that a particular village in Vietnam, Ben Tre, had to be extirpated: “It became necessary to destroy the town to save it” (from the Vietcong), sayeth the major (according to Arnett). This has entered American discourse as “we had to destroy the village to save it.”

That phrase came to mind when contemplating the havoc wreaked by the CCP Virus. Europe is shutting down, country by country. Parts of the US have shut down. Others are on the verge of shutting down. The economic carnage is immense. Governments talk of spending trillions of dollars in various forms of relief: the loss of output/income will probably be measured in trillions.

Contra Hayek, it is the curious task of an economist to ask whether it’s worth it. That is, economics is predicated on the concept of scarcity, which in turn implies that every choice involves a trade-off. You want more of a good–or in the present instance, less of a bad–you have to give up something.

What price are you willing to pay? How much is saving 1000 lives worth? 10,000?

Orders of magnitude. Let’s say that shutting down the US economy through radical social distancing, quarantines, etc., saves 1000 lives, and costs $1 trillion. That works out to $1 billion per life. Moreover, the lives saved are most likely aged, infirm, sick individuals with short life expectancies and poor life quality.

Is that a price you are willing to pay? There is no right answer: the answer is subjective. Your answer may differ from mine. But when making decisions, it is a question we have to answer.

Increase the death toll by 10, and you are still at $100 million/life. This is far beyond any value of life estimate used in other regulatory and policy decisions.

If the cost of an economic shutdown is $1 trillion, you would have to save on the order of 100,000 lives to approximate the value of a statistical life (around $10 million) the US government uses for other policy making purposes.

I know that most people recoil at such calculations. The idea of valuing lives in dollars violates most people’s moral intuitions.

So let’s focus on lives. A major recession–or depression, which is not inconceivable–costs lives. Suicide rates go up. Substance abuse goes up, which costs lives in the near term (overdoses, fatal vehicle accidents) and the long term (substance abuse shortens lives). Stress-related fatalities (heart attack, stroke) go up. Murder rates go up. Consumption of health care declines, leading to premature deaths.

And then we can start talking about quality of life.

Pretty soon it adds up. We are not just evaluating the trade-off of lives for money. We are evaluating the trade-off of lives for lives.

That is, always remember Bastiat: think of the unseen. There is an unseen public health cost associated with major economic dislocation. That unseen cost has to be weighed against the cost that is right in front of our faces at present, i.e., the death toll from CPCV-19/20.

It is of course difficult to estimate, or even approximate, the various costs. Our radical ignorance about the virus makes it difficult to assess what the death toll would be under various policies. Similarly, we are operating in completely unexplored territory in trying to estimate the economic cost, let alone the health cost, of more or less draconian restrictions on our lives and movement.

But we have to at least confront the trade-off. Acknowledge it. Grapple with it. My strong sense is that the monomaniacal focus on controlling spread of the virus, the costs be damned, is operating according to the logic of destroying society in order to save it. That logic was absurd in 1968. It is absurd in 2020.

March 18, 2020

The Banality of Vova

So forget all of that stuff about what workaround Putin was going to employ to remain de facto president for life: he has found a workaround to make himself de jure president for life.

It’s comical in a way. Start a process to amend the constitution of the Russian Federation. Get a respected Soviet-era fossil in the Duma, astronaut Valentina Tereshkova, to introduce an Orwellian Memory Hole amendment. Specifically, that anyone is eligible for two consecutive future presidential terms, thereby consigning Putin’s previous/current consecutive terms to the Memory Hole.

Then get Vova to address the Duma, and say (in effect): oh shucks, guys, I’ll accept if you insist. But only if the Constitutional Court agrees! Which is sort of like the organ grinder saying he’ll accept tips only if the monkey dances.

And, of course, yesterday the monkey danced.

The entire process has been completely banal, and lacking of the frisson that would accompany weighty constitutional changes in other countries.

This all transpired with a (predictable?) lack of response from the Russian populace. Likely because they know responding is worthless. If you know the game is rigged, what’s the point of protesting?

This raises only the question of why Putin went through such machinations in January. My conjecture is that those were mainly trial balloons. He clearly signaled that he was looking for a way to remain in power indefinitely. These signals were met with a collective shrug, except from a completely irrelevant opposition. Seeing this, Putin figured (IMO) that there was no political need for subterfuge: take the direct route and retain presidential power. Which also had the benefit of eliminating ambiguity about the distribution of power going forward.

So Russia shrugs, and Putin moves on: unlike an adage that Putin favors, he did not even hear any dogs barking. A further illustration of the maxim that nations get the leaders they deserve.

Insofar as the US is concerned, this is probably the best outcome. A succession struggle in a hostile nuclear power is not a happy prospect. And it’s not a bad thing when a self-proclaimed rival is in the hands of an aging man (in a country where men do not age well) whose mental powers will diminish and who will become more risk averse/conservative with age.

A banal Russia in the hands of a president who retains his powers as a result of an utterly banal process is not a good thing for Russians. But it is not a bad thing for the rest of the world.

March 14, 2020

Test This

One of the refrains we’ve heard repeatedly during the Panicdemic (which is arguably worse than the pandemic) is: “We Need More Tests! We Need More Tests!”

There is a Chicken Little vibe to these calls for testing. A sense that people are running around like the sky is falling, and not thinking through the right testing strategy.

What are tests for? One is for diagnostic purposes in specific cases. To be frank, the value of such tests is minimal. There is no unique therapy for acute Wuhan Virus sufferers. The protocol is to treat the symptoms of acute respiratory distress the same way as one would treat such distress from other causes. So knowing that someone’s acute distress is caused by agent X as opposed to agent Y is of limited therapeutic value.

Insofar as identifying someone expressing symptoms would help identify others so exposed, a much more efficient strategy is to presume that the symptomatic individual is suffering from WV, track his/her contacts, and monitor and quarantine said individuals accordingly. Yes, there will be Type I (false positive) errors, but the cost of such errors is likely to be relatively small if an individual is suffering from an acute condition, regardless of the exact pathogen that caused it. That pathogen is obviously capable of causing severe problems, so why not isolate those exposed to it, even if you don’t know exactly what it is?

Another purpose of testing is to collect information about the prevalence, virulence, contagiousness, and fatality of the disease. Such information can be used to optimize the policy response.

Testing those who are symptomatic and/or have been exposed is exactly the wrong way to go about that. Such a testing strategy is rife with sample selection bias.

For weeks (mainly on Twitter) I advocated construction of a random panel data set. Select people at random. Test them, and test them at regular intervals–including those who tested negative. This would provide an unbiased sample that would permit more reasoned assessments and judgments about the nature of the pathogen. We could see how many people had contracted the virus, how many people they infected, the mortality rate (and how the mortality rate varied with age, health status, etc.), and the trajectory of the virus.

If that had been done, say, in January when shit started to get real in China, perhaps we could have been able to condition policy on better information. (Not to mention if the CCP had done that in, say, December, when it knew it had a problem on its hands–but decided to suppress information rather than suppress the pathogen.)

Why didn’t our Technocrats figure this out? Yeah. We should put more of our lives in their hands.

But that opportunity to get unbiased data has passed. Now we are forced to respond based on the most sketchy and biased data. Chicken Little proposals about testing will generate . . . more biased data. Which is arguably worse than useless.

March 13, 2020

Wuhan Virus and the Markets–WTF?

What a helluva few weeks it’s been, eh boys and girls? By way of post mortem (hopefully?) rather than prediction, here’s my take.

Under “normal” circumstances, two factors drive asset valuations: expectations of cash flows, and the rate at which investors discount those cash flows. COVID-19–Wuhan Virus, to call it by its proper name–has has profound influence on both.

WV has caused a major aggregate supply shock, and an aggregate demand shock, and these amplify one another. The aggregate supply shock stems from shutdown of productive capacity due to social distancing. And people who aren’t working aren’t earning and aren’t spending, hence the aggregate demand shock.

These developments obviously reduce the income streams from assets (e.g., corporate profits). That’s a negative for stocks.

As an aside, these factors defy traditional policy prescriptions. Monetary and fiscal policy are focused on addressing aggregate demand deficiencies, i.e., trying to move demand-deficient economies (where demand deficiencies arise from price rigidity and nominal shocks) back to the production possibilities frontier. Supply shocks shrink the PPF. Pushing the PPF back to its normal state in current circumstances is a function of public health policy, and even that is likely to be problematic given the huge uncertainties (that I discuss below) and the dubious competence of government authorities (which I discussed last week).

The pandemic nature of WV also makes it the systematic shock par excellence. It hits everyone and every asset class, and cannot be diversified away. A big increase in systematic risk results in a big increase in risk premia, meaning that the already depressed expected cash flows on risky assets get discounted at a higher rate, leading to lower valuations.

A lot higher rate, evidently. Why? Most likely because of the extreme uncertainty about the virus. Data on how infectious it is, how many people have been infected, the fatality rate, how it will be affected by warmer weather, etc., are extremely unreliable. In other words, we know almost nothing about the salient considerations.

This is in part due to lack of testing, and to inherent defects in the testing: those who get tested are disproportionately likely to be symptomatic, exposed, or hypochondriacal, leading to extreme sample selection biases. The tests are apparently unreliable, with high rates of false positives and false negatives. The RNA tests cannot detect past infections. It is in part due to the novelty of the virus. Is it like influenza, and will hence burn out when temperatures warm? Or not?

Another major source of uncertainty is due to the fact that the initial outbreak in China was covered up by the evil CCP regime. (Which now, in an Orwellian twistedness that only totalitarian regimes can muster, is boasting that it will save the world. And which is blaming the United States for its own abject failures. Which is why I insist on calling it the Wuhan Virus–so go ahead, call me a racist. IDGAF.) Thus, data from Ground Zero is lacking, or wildly unreliable. (Ground One–Iran–is equally duplicitous, and equally malign.)

This huge uncertainty regarding a major systematic factor leads to even greater discount rates–and hence to lower stock prices.

And then there is the truly disturbing factor. These textbook causal channels (lower expected cash flows, higher discount rates) have in turn caused changes in asset prices that force portfolio adjustments that move us into the realm of positive feedback mechanisms (which usually have negative effects!) and non-linearities. This represents a shift from “normal” times to decidedly abnormal ones.

When some investors engage in leveraged trading strategies, big price moves can force them to unwind/liquidate these strategies because they can no longer fund their large losses. These unwinds move asset prices yet more (as those who placed a lower valuation on these assets must absorb them from the levered, high-value owners who are forced to sell them). Which can force further unwinds, in perhaps completely unrelated assets.

Not knowing the extent or nature of these trading strategies, or the degree of leverage, it is virtually impossible to understand how these effects may cascade through the markets.

The most evident indicators of these stresses are in the funding markets. And we are seeing such stresses. The FRA-OIS spread (known in a previous incarnation–e.g., 2008–as the LIBOR-OIS spread) has blown out. Dollar swap rates are blowing out. The most vanilla of spreads–the basis net of carry between Treasury futures and the cheapest-to-deliver Treasury–have blown out. Further, the Fed has pumped in huge amounts liquidity into the system, and these alarming spread movements have not reversed. (One shudders to think they would have been worse absent such intervention.)

One thing to keep an eye on is derivatives clearing. As I warned repeatedly during the drive to mandate clearing, the true test of this mechanism is during periods of market disruption when large price moves trigger large margin calls.

Heretofore the clearing system seems to have operated without disruption. I note, however, that the strains in the funding markets likely reflect in part the need for liquidity to make margin calls. Big margin calls that must be met in near real-time contribute to stresses in the funding markets. Clearinghouses themselves may survive, but at the cost of imposing huge costs elsewhere in the financial system. (In my earlier writing on the systemic impacts of clearing mandates, I referred to this as the Levee Effect.)

The totally unnecessary side-show in the oil markets, where Putin and Mohammed bin Salman are waging an insane grudge match, is only contributing to these margin call-related strains. (Noticing a theme here? Authoritarian governments obsessed with control and “stability” have a preternatural disposition to creating chaos.)

Perhaps the only saving grace now, as opposed to 2008, is that the shock did not arise originally from the credit and liquidity supply sector, i.e., banks and shadow banks. But the credit/liquidity supply sector is clearly under strain, and if parts of it break under that strain yet another round of extremely disruptive knock-on effects will occur. Fortunately, this is one area where central banks can palliate, if not eliminate, the strains. (I say can, because being run by humans, there is no guarantee they will.)

Viruses operate according to their own imperatives, and the imperatives of one virus can differ dramatically from those of others. Pandemic shocks are inherently systematic risks, and the nature of the current risk is only dimly understood because we do not understand the imperatives of this particular virus. Indeed, it might be fair to put it in the category of Knightian Uncertainty, rather than risk. The shock is big enough to trigger non-linear feedbacks, which are themselves virtually impossible to predict.

In other words. We’ve been on a helluva ride. We’re in for a helluva right. Strap it tight, folks.

March 9, 2020

Why Are Equities and Oil Moving the Same Direction After an Oil Supply Shock?

The collapse in oil prices is completely understandable. The co-movement in equity and bond yields is harder to fathom.

As I noted in a previous post, the initial sell-off in oil was driven by corona-related demand declines. One thing interesting at the time was that equities did not respond similarly, which suggested that the prevailing view was that the situation would be contained in China. The last few weeks, equities and bond yields caught up, presumably due to the spread of the virus outside of China (especially in Italy).

The main oil-related news was a big supply shock–the prospect for higher Saudi and Russian output. But this should be positive for the economy overall, and thus for equities. There does not seem to be any new virus-related news that would lead to predictions of a sharp reduction in incomes and output. So, by itself, the oil supply shock should not cause a large sell-off in equities and big buying of bonds. But that is what we are seeing.

One can imagine other channels, e.g., losses on oil positions causing liquidation of equity positions. But the oil markets likely aren’t large enough to trigger such a reaction, and this channel would require those who are long equities to be long oil too–and in a big way in both.

Focusing on the oil supply shock in particular, I wonder if Putin and the Russians expected the furious Saudi reaction. The ruble is down 5+ percent today. Amusingly, Russian cat’s paw Zerohedge is claiming that Putin is all copacetic with this, saying that Russia can survive $25/bbl oil prices for a decade.

This is putting a brave face on things. And those with long memories will recall similar statements during the 2008-2009 collapse–statements that proved laughably false.

It is also interesting to note that Russian expressions of confidence relate to the state budget. Maybe the fiscal frugality has indeed positioned the government to live lean. The populace, not so much. But that’s very revealing about the mindset of the Russian ruling class: it is all about the state, utterly state-centric, and largely dismissive of the citizenry. And it has been so, as long as there has been a Russia.

March 8, 2020

There Will Be Blood

As a coda to the post on the bloodbath in oil. I remember how many Smart People claimed that Putin’s alliance with MbS’s Saudi Arabia was an act of strategic genius! Genius I say! The move of a 4 dimensional chess grandmaster. A move that went a long way to achieving Russian dominance in the Middle East, at the expense of the US.

Er, no. Like almost all of Putin’s moves, it was an act of short term opportunism, and one that was built on a foundation of sand (appropriate, given the locale). MbS was being equally opportunistic, and his and Putin’s short-term interests aligned. But cartels–and this was little more than a cartel with a little geopolitical gloss–are inherently unstable, and the interests of the colluders are inherently in conflict. Inevitably such condominiums collapse.

Inevitably.

And so has this one. It was merely a matter of time, and what the proximate cause of the collapse would be.

There was no enduring alignment of interests that would provide the basis for a strategic realignment. There was a momentary alignment of interests between oil ticks. A market shock (extremely unexpected, no doubt) smashed the delicate structure to pieces.

The furious Saudi reaction to the Russian move demonstrates how fleeting Putin’s gains were. MbS is well and truly pissed, and looking to take revenge.

The only question that remains is: who will drink whose milkshake?

Erdoğan Harvests the Fruits of His Strategic Genius

Apropos my earlier post on Erdoğan’s strategic brilliance, after Turkey’s army inflicted some serious damage on Assad’s armed forces, the Russians evidently made it clear that he would not be allowed to have his way in Idlib. So Erdoğan scuttled to Moscow, and emerged with a ceasefire agreement (not that he wanted one) which basically brought his campaign to a screeching halt.

The optics tell all. The fact that Erdo had to go to Moscow for one thing. But it was worse than that. Putin really rubbed the would-be sultan’s nose in it.

The same week a delegation from Zimbabwe–yes, Zimbabwe–visited Putin in the Kremlin. The entire delegation was seated. There was no statuary in sight.

When the Turkish delegation visited, all except Erdoğan were forced to stand. In front of a statue of Catherine the Great, no less, which had been moved into the room specifically for the Turkish delegation.

Catherine, of course, waged war against the Ottomans during her entire reign, and seized vast territories from them. Catherine epitomizes Russian domination of Turkey. As Russians well know–as do Turks.

After leaving the Turks to shuffle cravenly before Catherine’s bronze gaze for a few moments, Putin beckoned them to approach with a dismissive wave of his fingers, like he was calling his dogs. He was trying to humiliate. He succeeded.

Erdoğan has been flailing desperately for US and European support to counter Russia. Trump acknowledged that Turkey and Syria were fighting, but said he didn’t care.

In so many words: You’re on your own, Erdo! You made your bed with Putin, hope you stocked up on the KY.

The refugee gambit has only infuriated the Europeans. Not as if they would be willing to risk confronting Russia anyways.

Yes. Quite the genius Erdo is. Quite the genius.

Note to VVP: US Shale’s Pain Does Not Equate to Russia’s Gain. Predatory Pricing Is Futile.

Oil is crashing, with WTI trading at a 33 handle, down 20+ percent since Friday.

The first leg down in oil prices was caused by the coronavirus demand shock in China. This most recent free-fall is a response to Russia’s refusal to agree with OPEC to extend the existing OPEC+ cuts, and deepen them in response to the demand decline; and the Saudis’ reaction to the Russians, specifically, to put the output pedal to the metal.

The Saudi reaction to the Russians is a classic cartel defector punishment strategy. The Russian demurral is more difficult to understand. One story circulating is that Putin wants to punish US shale. If so, he’s a fool. And worse, a fool who fails to learn from the foolishness of others, e.g., the Saudis whose predatory pricing strategy in 2014-2016 failed miserably.

Yes, cratering the price of oil will inflict pain on US shale producers. They will suffer financial losses, and will curtail drilling and output. But US pain does not equate to Russian gain. Russia will incur substantial losses from prices in the 30s–and more pain if prices go into the 20s, as is possible. But Russia will not recoup this pain with future gains. If and when they (and OPEC) decide they’ve had enough, and curtail output to raise prices, US output will respond accordingly.

US rocks can outwait Putin. Yes, the US shale supply chain will be damaged reduced activity, and will take some time to recover, but as the Saudis found out in 2016, the flexibility of the US oil sector allowed it to rebound extremely rapidly when prices rose. The resource remained. The human capital remained. When OPEC+ went into effect, US oil output soon exceeded the pre-2014 price crash levels, which sharply limited the upside for the Saudis and Russians.

I am currently putting finishing touches on a paper which, among other things, demonstrates the futility of the Saudi strategy in 2014–and the Russian strategy (if that’s what it is) today. I document learning-by-doing economies in the US shale sector. If these economies are big enough, lost output today due to predatory Saudi or Russian behavior translates into lower US productivity in the future. That means that Saudi/Russian price cutting today raises their rivals’ costs in the future, which could lead to higher future Saudi/Russian profits then.

But the empirical estimates show that the US productivity losses due to foregone learning are very small, and hardly allow the predators to recoup the huge costs they incur from their predatory strategies. Putting the Saudis and Russians together, $10/bbl price cuts today cost them on the order of $230 million/day: $20/bbl cuts cost them around $460 million/day. There is no way that the higher future cost of US oil production due to lost learning opportunities will allow the predators to recoup these losses in the future by raising the ceiling that US shale puts on world oil prices.

Predatory pricing strategies are almost always futile. They are definitely futile with regards to the US shale sector. If Putin is indeed pursuing a predatory path, he is cutting off his own nose to spite his face.

So go ahead, Vova. Knock yourself out.

March 2, 2020

Be Careful What You Ask For, Progressives: A Failure of the US to Respond to Coronavirus Would Discredit the Progressive Worldview, Not Trump

The latest leftist/statist/progressive/establishment/”elite” freakout is over Trump’s alleged incompetence at addressing the Coronavirus. This is an illustration of their utter cluelessness, because the responsibility for any failure in addressing a potential pandemic utterly discredits the entire progressive vision.

In that vision, a wise, nay, omniscient, technocratic elite foresees problems, devises elegant solutions, and saves the world. In that vision, elected officials–legislators, but especially the chief executive–are at best irrelevant distractions, but more likely meddling interferers who undermine the brilliant designs of the administrative apparatus.

So if the government fails, it is on the permanent government, not on the hapless sod at the top who vainly pulls the levers of the state machinery, to no avail (because the mandarins are far too sophisticated to respond to the commands of such a boorish boob–they know better!).

We already have a perfect illustration of the disconnect between the vanity of the administrative state and its actual competence. The geniuses from the government who are here to help put infected individuals from a cruise ship on an aircraft . . . that also carried (previously!) non-infected individuals. The response of the State Department is priceless. It should be framed for posterity:

“At the end of the day, the State Department had a decision to make, informed by our inter-agency partners, and we went ahead and made that decision,” Walters said. “And the decision, I think, was the right one in bringing those people home.”

Again with the fucking “inter-agency”! Our overlords to whom we owe utter obeisance.!

But there’s more from M. Walters:

“What I’d say is that the chief of mission, right, through the U.S. embassy, is ultimately the head of all executive branch activities. [Er, mere peasant that I am, I thought from reading the Constitution that the President of the United States is “ultimately the head of all executive branch activities.” Silly me!] So when we are very careful about taking responsibility for the decision, the State Department is – that is the embassy. The State Department was running the aviation mission, and the decision to put the people into that isolation area initially to provide some time for discussion and for onward, afterwards, is a State Department decision.”

Yes, we are in the best of hands. The best of hands! How dare you question them, peasant!

Regardless of what you think about Trump’s competence, it cannot be less than the bureaucracy’s. Yet the better thans insist on demanding we defer to the bureaucracy. Because they know better.

And then, they are shocked–shocked!–when people with a modicum of common sense and who rely on empirical reality choose Trump over them.

Maybe you could be this stupid. And arrogant. If you tried really, really hard.

Craig Pirrong's Blog

- Craig Pirrong's profile

- 2 followers