Craig Pirrong's Blog, page 24

November 25, 2022

The Apotheosis of My Family’s Civil War Service

25 November 1863 was the high point of my distaff side’s Civil War service.* Three of my ancestral relatives fought on that day at the Battle of Missionary Ridge at Chattanooga, Tennessee.

My grandmother’s grandfather George Immel fought in the 92nd Ohio Volunteer Infantry. This regiment was part of Turchin’s Brigade, Baird’s Division, XIV Army Corps (commanded by John M. Palmer), Army of the Cumberland. It was one of the regiments that made what at the time seemed to be the insane attack up the precipitous ridge, but which resulted in the routing of the Rebels: when seeing the Cumberlanders commencing their scaling of the ridge without orders, Ulysses S. Grant bit down on his omnipresent cigar and muttered that someone would pay if the attack became a bloody shambles, as he expected. But it didn’t end that way. To the amazement of all, the Confederates fled before the charging Unionists.

Immel had enlisted at 18 years of age over the vehement protests of his parents: they could not understand why he would do so because they had emigrated from Hesse precisely to protect their sons from military conscription. He said I am a free American now and enlisted of his own free will. He served through the war, supposedly (according to family lore) serving at one point as General Ivan Basilovich Turchin’s courier, though I have not been able to document that. (Turchin–his name anglicized to John Basil Turchin–is one of the war’s remarkable characters, as was his wife. Since his wife traveled with the general, if George was Turchin’s courier he would have known her.)

The war memories he passed down were of the Battle of Chickamauga, of which he related that his main memory was of the continuous roar of gunfire for two days. Turchin’s brigade distinguished itself in the battle, repelling several Confederate assaults, and at the end of the day mounting a wild charge that opened the way for the rest of the beleaguered XIV Corps to escape.

This is a Don Troiani print of Cleburne’s Confederate division fighting at Chickamauga. In the print, Cleburne is passing out ammunition to shoot at my GGGF, because Cleburne’s division was attacking the 92nd’s position:

The other memory passed down is that of Sherman’s march through the Carolinas, when he picked up lots of booty, including a Confederate sword, but it got too damn heavy to carry so he disposed of it. Meaning that the only thing that he brought back from the war was a case of rheumatism which plagued him the rest of his life.

My grandmother remembered him well. He was a stern Teutonic figure (you can take the boy out of Germany but can’t take the Germany out of the boy, apparently) who whipped his grandchildren every Christmas eve to punish them for their sins of the prior year. He married a woman of English heritage, and according to my grandmother they fought constantly. Her grandmother said: “Well, the Germans and the English always fight.” They did more than fight apparently, because they had 8 children: or maybe that was the result of the fighting, if you know what I mean.

Ironically, the attack that the Army of the Cumberland mounted up Missionary Ridge was initially planned as a limited operation to relieve pressure on Union forces fighting about a mile up the ridge which included my grandfather’s uncles, members of the 46th Ohio Volunteer Infantry. The 46th was in Corse’s Brigade, Ewing’s Division, XV Corps, operating under the command of William T. Sherman (who is, by the way, a distant relative via a shared ancestor who settled in Connecticut in 1635–my GGGM’s name was Lois Sherman, and her father was Eli Sherman).

On the 24th, Grant assigned Sherman the limited objective of establishing a position at the north end of Missionary Ridge and digging in. Due to a misunderstanding of the ground (that was not directly visible from where Grant and Sherman stood when concocting the plan), Sherman’s forces dug in on a hill (Billy Goat Hill) that was separated from the north end of Missionary by a wide swale. The next morning, Grant revised Sherman’s orders and commanded an attack up the ridge. Sherman assigned Corse’s brigade for the task.

The ridge was so narrow that the entire brigade could not deploy in line, but assaulted in column of regiments against . . . the same Patrick Cleburne who had attacked George Immel two months prior. Cleburne beat back Corse’s attack, and the attack of other brigades that Sherman sent against him.

Walking over the terrain you can see that it was a futile effort. But everyone thought that the Army of the Cumberland’s charge would be futile too.

My grandfather never knew his uncles. One, Eli Hatfield (named after his maternal grandfather), was apparently something of a sad sack. He was captured at Shiloh, spent a few months in a Rebel prison camp (Cahaba in Alabama) before being paroled. He complained that prison had ruined his health, and his file contains several doctor’s notes claiming he was unfit for service. This worked for about a year, but eventually his appeals were unavailing and he was ordered to rejoin the regiment shortly before the Battle of Chattanooga. After the battle, he was assigned as a teamster (something that company commanders sometimes did to get rid of screwups), and was fined $20 for losing his accoutrements (cartridge box and belt).

Far less comically, on 27 May 1864 Eli was shot at the Battle of Dallas (Georgia). The bullet struck him in the left arm right below the shoulder joint. Minie balls were large, low velocity projectiles that shattered bone, and hence Eli’s arm was pulverized. The wound was too close to the shoulder for amputation, so all of the bone between the shoulder and the elbow was resected. My great grandmother told my grandfather about his “Uncle Eli with the dead arm from the war,” and how when he would sit down at a table he would grab his (useless) left hand with his right, and then put his left forearm on the table. He lived until around the turn of the century.

(The details about his wound are from a report that the surgeon who operated on him filed, and which is retained in his service record at the National Archives. The letter is a full page in length. I’ve often wondered about how tiresome and dreary a task it would have been to write such letters, especially considering the exhaustion that the surgeon surely suffered in the midst of a long and bloody campaign.)

The other uncle, John Hatfield, returned to Athens County, Ohio after serving the remainder of the war. He fought at Shiloh, Vicksburg, Chattanooga, the Atlanta Campaign (including the Battle of Resaca, The Battle of Dallas, the assault at Kennesaw Mountain, the Battle of Atlanta, the Battle of Ezra Church, and the Battle of Jonesboro), the March to the Sea (including the Battle of Griswoldsville, the largest of the campaign), and the March Through the Carolinas, never receiving a scratch. Unlike his brother’s, his service record is dull: just appearances on the regular muster rolls, with nary an absence noted. He eventually made it to the exalted rank of corporal.

Farming or coal mining in Ohio (his father was a coal miner, as his younger brothers became) apparently didn’t appeal to him, so not long after the war he set off for Kansas. His sister never saw him again.

To round out the story, after seizing the top of the ridge, along with the rest of Baird’s division the 92nd pivoted left, moved north, and drove Cleburne’s division from the ridge where it had held off the 46th. So as darkness fell on an overcast and gloomy 25 November 1863, unbeknownst to them, my ancestors were looking at one another across the field of one of the Union’s most spectacular triumphs of the Civil War.**

*Well, that means that the acme of my entire family’s Civil War service occurred 159 years ago today, because all of my father’s ancestors arrived after the Civil War, the earliest in 1867.

**The Hatfield and Immel families intersected about 62 years after a few of their members were looking at each other through the smoke and haze on Missionary Ridge: my grandparents married on 2 January 1925.

November 16, 2022

Biden’s Latest Energy Brainwave: Engrossing Diesel!

US President Joe Biden is considering forcing the nation’s fuel suppliers to keep a minimum level of inventory in tanks this winter as a means of preventing heating oil shortages and keeping prices affordable. It may actually do the opposite.

Well actually actually, there’s no “may” about it. It will, if the administration indeed forces away.

As I’ve written previously, there are times when economic conditions make it optimal to hold low (and perhaps no) inventories. When the supply/demand balance is expected to improve in the future, holding inventories moves a commodity from when it is relatively scarce, to when it is relatively abundant. It is better to do the opposite. But since you cannot transport future production to meet present consumption, the best thing to do is to draw down inventories–perhaps to zero.

There is no reason to believe that the market has “failed” to respond efficiently to fundamental conditions. There is absolutely no reason to believe that Joe Biden or anyone who works for him has solved the Knowledge Problem and knows how to allocate scarce diesel over time better than the markets do. Do you really think Joe et al know that the supply/demand balance in diesel is actually going to get worse, when the market judgment is the opposite? If you do, seek help.

So yes, if carried out, this action would increase spot prices because the only way to increase inventories is to reduce current consumption, and the only way to increase current consumption is through higher spot prices. Further, this action would tend to depress deferred prices because it will increase future consumption.

So if he does this, it would be totally correct to put one of those “I did that” stickers on a diesel pump.

It’s ironic to note that mandatory government stockholding programs, sometimes seen in agricultural markets, are intended to increase prices (to help farmers, for instance). It’s also ironic that Biden is floating this after months of drawing down on government inventories of crude in the SPR–in order to reduce prices.

What Biden is proposing could be seen as a government run corner: the antitrust case of U.S. v. Patten (1913) identifies one of the salient features of a corner as “withholding [a commodity] from sale for a limited time” with the purpose of “artificially enhancing the price.” Biden is proposing “withholding” diesel from the market.

Or, using more archaic language, it is government run “engrossing” or “forestalling,” something that speculators are often (wrongly) accused of, as Adam Smith wrote about in The Wealth of Nations.

The only good news to report here is apparently market participants think this idea is so stupid that not even this administration will implement it. Diesel flat prices and calendar spreads haven’t moved much after Biden’s announcement.

But it would be much better if the administration actually had some good ideas rather than a stream of bad ones, some of which are so obviously bad that they will never come to fruition.

November 14, 2022

Regulate This! Yeah? How?

As day follows night, the vaporization of FTX has spurred calls for regulation of crypto markets. Well, what kind of regulation, exactly? It matters.

It appears highly likely that SBF and his Merry Gang (of pervy druggies?) broke oodles of laws, in multiple jurisdictions. Class action lawsuits are definitely incoming, and the DOJ’s SDNY attorneys’ office is commencing a criminal investigation. No doubt criminal investigations will follow in other locations. So what would more laws accomplish, and what kind of laws and regulations would help?

It is interesting to note that SBF was going around DC and the media talking up regulating the industry, and winning effusive plaudits (but not from CZ!) for doing so, but his proposals didn’t come within a million miles of his alleged wrongdoing. I’m sure you’re shocked.

On CNBC, Bankman-Fried endorsed three regulatory endeavors: stablecoin auditing, “markets regulation” of spot trading, and token registration (at about the 4:30 mark):

None of which touches on the fundamental issue in the FTX fiasco, and in crypto market structure generally: the role of “exchanges” in supplying broker dealer and banking services, including liquidity, maturity, and credit transformations.

No doubt SBF was adding to his savior glow by pushing regulation that he knew was utterly irrelevant to the core of his business (and the business of all other crypto “exchanges”). And look at how many suckers fell for it.

So what would help? As I noted at the outset, FTX, Bankman-Fried, et al likely violated numerous laws. So what additional laws would reduce the likelihood and severity of such actions?

In thinking about this, remembering the distinction between ex ante and ex post regulation is important. Ex post regulation involves the imposition of sanctions on malfeasors after they have been found to have committed offense: the idea is to deter bad conduct through punishment after the fact. In contrast, ex ante regulation attempts to prevent bad acts by imposing various constraints on potential wrongdoers.

The choice between ex ante and ex post depends on a variety of factors. Two of the most important (and related) are whether the bad actor is judgment proof (i.e., will have the resources to recompense those he has harmed) and the probability of detection. (These are related because a low probability of detection requires a higher penalty to achieve deterrence, but a higher penalty increases the chances that the wrongdoer is judgment proof).

In the case of things like what has apparently happened here, the probability of detection is high (1.00 actually), but the magnitude of the harm is so great and the (negative) correlation between the harm and the wrongdoer’s ability to pay is so high (essentially -1.00) that ex post deterrence is problematic.

(Judgment proof-ness is actually a justification for criminal law and the use of incarceration as punishment. Deterrence through fines doesn’t work with broke bad guys, so non-monetary punishment is necessary–but often not sufficient!)

So there is a case for ex ante regulation here, just as there is a case for ex ante regulation of banks and intermediaries like broker dealers and FCMs. Banking examiners, regulatory audits, customer seg rules, and the like.

But these are obviously not panaceas. Bank fraud still occurs with depressing regularity, and the things that facilitate it, like valuation challenges, accounting shenanigans, and so on, occur in spades in crypto. And, even in highly regulated US markets, violation of seg rules and misuse of customer assets occurs: yeah, I’m looking at you John Corzine/MF Global.

The big problems in crypto markets are essentially agency problems, especially since the crucial agents–crypto “exchanges”–are so concentrated and so vertically integrated into both execution and various forms of financial transformations.

Ex ante regulation focused on such issues could be a boon, and could help stabilize crypto markets generally. The spillovers we are seeing from FTX’s vaporization are essentially a reputational contagion: the mini (so far) runs on other “exchanges” reflect FUD about their probity and solvency. (NB: Binance, as the biggest “exchange,” and as opaque as FTX, is a serious run risk. BlockFi and AAX may already be in the crosshairs here: glitch in the systems upgrade. Riiiiigggghhhht.)

The challenge is that the demise of financial intermediaries is well-described by a famous Hemingway quote:

“How did you go bankrupt?” Bill asked. “Two ways,” Mike said. “Gradually, then suddenly.”

An intermediary can go along swimmingly, meeting all seg requirements and the like, and a big market move or bad bet or an operational SNAFU can put it on the brink very suddenly–and encourage gambling for resurrection by using customer funds to extend and pretend. So don’t expect such regulation to be a panacea, and prevent the recurrence of FTXs. Regulation or no, this happens with intermediaries that engage in liquidity, maturity, and credit transformations that are inherently fragile. (And may be fragile by design, as Doug Diamond has pointed out.)

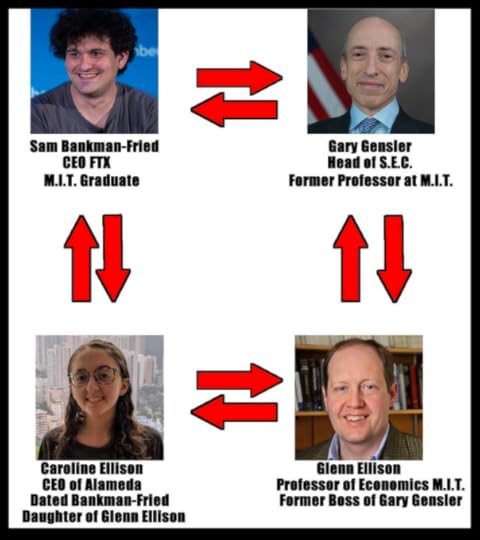

On the regulation issue, one fascinating sidebar is my old bête noire, Gary Gensler. You don’t need to play 6 Degrees From SBF to ensnare most of the Democratic establishment: one or two degrees will do, and Gensler definitely qualifies.

In addition to the MIT connection, Gensler apparently had other interactions with Bankman-Fried. And of course Gensler is a player in the Democratic Party (he was Hillary’s campaign’s finance chair, after all), and Bankman-Fried was a major Dem donor (second largest after Soros in the most recent cycle, and he had talked about spending up to a billion in the 2024 campaign).

When initially questioned about FTX, Gensler was very defensive: “Building the evidence, building the facts often takes time.”

I am reserving judgment, but I hope someone takes the time to examine the links and interactions between SBF/FTX and Gensler (and other DC creatures)–and build the evidence and facts, if it comes to that.

My guess is that Gensler will try to pull a judo move and use this fiasco as a justification for expanding the power of the SEC. Indeed, I expect him to be in high dudgeon precisely to deflect attention from his (and his party’s) links to SBF. Don’t let him get away with it.

And don’t think that these links can be exposed through a FOIA. Gensler has long been known for using his private email to conduct official business. (Which is precisely why I didn’t bother FOAI-ing him years ago regarding my suspicions of his interactions with David Kocieniewski.) So deeper digging is required, and it should commence, post haste.

November 10, 2022

Another Blizzard in Crypto Winter, or, Tinker Bell Economics: To Call Crypto a “Trustless” System is a Joke

Another blizzard hit the winter-bound crypto industry, with the evisceration of crypto wonder boy Sam Bankman-Fried’s (SBF to crypto kiddies) FTX and its associated hedge fund Alameda Capital. (Which should be renamed Alameda No Capital.) The coup coup de grâce was delivered by SBF’s former frenemy (now full fledged enemy), Binance’s Changpeng Zhao (CZ, ditto). But it is now evident that FTX was a Rube Goldberg monstrosity and all CZ did was remove–call into question, really–one piece of the contraption which led to its failure.

The events bring out in sharp detail many crucial aspects of the crypto landscape. (I won’t say “ecosystem”–a nauseating word.).

One is crypto market structure. FTX (and Binance for that matter) are commonly referred to as “exchanges,” giving rise to thoughts of the CME or NYSE. But they are much more than that. FTX (and other crypto “exchanges”) are in fact highly integrated financial institutions that combine the functions of trade execution platform (an exchange qua exchange), a broker dealer/FCM, clearinghouse, and custodian. And in FTX’s case, it also was affiliated with a massive crypto-focused hedge fund, the aforementioned Alameda.

Crucially, as part of its broker dealer/FCM operation, FTX engaged in margin lending to customers. Indeed, it permitted very high leverage:

FTX offers high leverage products and tokens. The exchange currently offers 20x maximum leverage, down from its previous 101x leverage products. This is still one of the highest maximum leverage a crypto exchange offers when compared to FTX’s other competitors. Leveraged long and short tokens for BTC, ETH, MATIC, and others are also offered by the exchange; for example, the ETHBULL token allows investors to trade a 3x long position in Ethereum.

FTX also engaged in the equivalent of securities lending: it lent out the BTC, etc., that customers held in their accounts there.

These are traditional broker dealer functions, and historically they are functions that have led to the collapse of such firms–more on that below.

FTX supersized the risks of these activities through one of its funding mechanisms, the FTT token. Ostensibly the benefits of owning FTT were reduced trading fees on the exchange, “airdrops” (a distribution of “free” tokens to those holding sufficient quantities on account with FTX, a promise to return a certain fraction of trading revenues to token holders by repurchasing (“burning”), and some limited governance/voting rights. The burning also served the function of limiting supply. (I plan to write a separate post on the economics of valuation of these tokens, though I do touch on some issues below.)

So FTT is (or should I say “was”?) stock-not-stock. Not a listed security, but an instrument that paid dividends in various forms.

FTT was in some ways the snowman here. For one thing, FTX allowed customers to post margin in FTT.

Huh, whut?

Risky collateral is always problematic. (Look at the reluctance of counterparties to accept anything but cash as collateral even from pension funds as in the UK.) Allowing posting of your own liability as collateral is more than problematic–it is insane. Very Enron-y!

Why? A subject I’ve written on a lot in the past: wrong way risk.

If for any reason FTT goes down, the value of collateral posted by customers goes down. Which means that your assets (loans to customers) go down in value.

A doom machine, in other words.

The integrated structure of FTX exacerbated this risk, and bigly. If customers start to get nervous about its viability, they start to pull the assets (BTC, ETH, etc.) they have on account there. Which is a problem if you’ve lent them out! (Recall that AIG’s biggest problem wasn’t CDS, but securities lending.)

And this has happened, with customers attempting to pull billions from the firm, and FTX therefore being forced to stop withdrawals.

And things can get even worse. The travails of a big broker dealer can impact prices, not just of its liabilities like FTT but of assets generally (stocks and bonds in a traditional market, crypto here) and given the posting of risky assets of collateral that can make the collateral shortfalls even worse. Fire sale effects are one reason for these price movements. In the case of crypto, the failure of a major crypto firm calls into question the viability of the asset class generally, with some of them being affected particularly acutely.

The integrated structure of crypto firms is also a problem. Customer assets are held in omnibus accounts, not segregated ones. Yeah yeah crypto firms say your assets on account are yours, but that’s true in a bookkeeping sense only. They are held in a pool. This structure incentivizes customers to run when the firm looks shaky. Which can turn looks into reality. That’s what has happened to FTX.

The connection with a hedge fund trading crypto is also a big problem. (The blow up of hedge funds operated by big banks was a harbinger of the GFC in August, 2008, recall.). And it is increasingly apparent that this was a major issue with FTX that interacted with the factors mentioned above. FTX evidently lent large amounts–$16 billion!–of customer assets to Alameda Research. Apparently to prop it up after huge losses in the first blizzards of Crypto Winter. (In retrospect, SBF’s buying binge earlier this year looks like gambling for resurrection.)

SBF described this as “a poor judgment call.”

You don’t say! I hear that’s what Napoleon said while trudging back from Russia in November 1812.

Also probably an illegal judgment call.

But it gets better! Alameda held large quantities of FTT, also apparently emergency funding provided by FTX. And it used billions of FTT as collateral for its trades and borrowing.

And this was the string that CZ pulled that caused the whole thing to unravel. When he announced that he had learned of Alameda’s large FTT position, and that as a result he was selling FTT the doom machine kicked into operation, and at hyper speed: doom occurred within days.

Looking at this in the immediate aftermath, my thought was that FTX was basically MF Global with an exchange operation. A financially fragile broker dealer combined with an exchange.

Think of MF Global operating an exchange.

— streetwiseprof (@streetwiseprof) November 8, 2022

And the analogy was even closer than I knew: FTX’s using customer assets to “fund risky bets” revealed this morning is also exactly what MF Global did. Except that Corzine was a piker by comparison. He filched almost exactly only 1/10th of what FTX did ($1.6 billion vs. $16 billion). (Maybe SBF should take comfort from the fact that Corzine walks free–though I don’t recommend that he walk free at LaSalle and Jackson or Wacker and Adams). (I further note that SBF is a huge Democrat donor. Like Corzine, his political connections may save him from the pokey, though by all appearances he should spend a very long stretch there.)

In sum, FTX’s implosion is just a crypto-flavored example of the collapse of an intermediary the likes of which has been seen multiple times over the (literally) centuries. As I’ve written before, there is nothing new under the financial sun.

The episode also throws a harsh light on the supposed novelty of crypto. Remember, the crypto narrative is that crypto is decentralized, and does not rely on trusted institutions: it is trustless in other words.

Wrong! As I’ve written before, economic forces lead to centralization and intermediation in crypto markets, just as in traditional financial markets. Market participants utilize the services of firms like FTX and Binance, and have to trust that those firms are acting prudently. If that trust is lost, disaster ensues.

In brief, crypto trading could be decentralized, but it isn’t. For reasons I wrote about years ago. (Also see here.)

Indeed, the issue is arguably even more acute in crypto markets, for a reason that SBF himself laid out in now infamous interview with Matt Levine on Odd Lots. Specifically, that token valuation relies on magic–belief, actually.

That is, tokens are valuable if people believe they are valuable–that is, if they have trust in their value. Furthermore, there is a sort of information cascade logic that can create market value: if people see that a token sells at a positive price–especially if it sells at a very large positive price–and they observe that supposedly smart people hold it, they conclude it must have some intrinsic value. So they pile in, increasing the value, validating beliefs, and extending the information cascade.

But this is Tinker Bell economics. If people stop believing, Tinker Bell dies.

And when someone very influential like CZ says “I don’t believe” death is rapid: the information cascade stops, then reverses. Especially given how FTT was the keystone of the FTX arch.

In brief, crypto theory is completely different than crypto reality. Crypto markets share all major features with the demonized traditional “trust-based” financial system. To the extent they differ, they are even more based on trust, given the ubiquity of Token Tinker Bell Economics.

November 3, 2022

The Real Political Implications of the Pelosi Beatdown

Has-been attention hound (I cleaned that up!) Hillary (this phrase would be just as alliterative if I had used the original word!) went onto the Joy Reid show to discuss political violence in the aftermath of hammer time with Paul Pelosi. She claimed that the attack on Pelosi is reflective of “a streak of violence, of racism, misogyny, antisemitism.”

Er, it was an attack on a white male Italian Catholic. 0 for 3 there, Hillary.

This demonstrates the intellectual laziness of the left. They are as predictable as my daughter’s old See and Say Barbie: pull the cord and the same phrases come out, time after time after time. Racism blah blah blah misogyny blah blah blah white supremacy blah blah blah.

But it’s more than just laziness: it’s a signal of who is beyond the pale. A signal that the people at whom these epithets are hurled so repetitively are to be shunned, ostracized, and worse. So facts don’t matter. There need be no basis for the assertion. They are nothing more than imprecations hurled at the hated. Marking with the sign of the beast.

It is beyond unseemly that the Democrats’ race to politicize the assault on Pelosi began within nanoseconds of its disclosure. With absolutely no basis, the Democrats and the media (pardon my stutter) pegged the assailant as driven to madness by MAGA.

No, by all appearances, he was driven to madness by madness, and had arrived at the destination years ago. And he lived in Berkeley for crissakes. The city with the lowest Trump vote in the nation. And those who did vote for him were probably so zonked out of their minds they didn’t realize what they were doing.

And though I will not speculate about the assault–I have questions! Which the SF police seem hell bent on not answering, refusing to release police body cam footage (the assault itself occurred after police had arrived) and home security footage. If it’s so open and shut, why the secrecy? (In a characteristic display of New Speak, the WaPo claims that releasing more evidence would feed conspiracy theories not dispel them. Riiiiggghhhht.)

It’s also interesting that the Feds swooped in to indict the perp, even though most of the crimes are clearly local in nature–B&E, assault with a deadly weapon, attempted murder, etc. No doubt given San Francisco’s very lenient bail policies the Feds want to make sure this guy stays on ice and doesn’t start blabbing. (This also protects the SF police and prosecutor from having to explain away double standards if they did not release the suspect, given they release pretty much everybody else.)

Speaking of ICE, since the politicization door has already been opened, it’s fascinating to note that the perp is an illegal alien. (A Canadian not MS13 or anything, but still–here illegally.). He overstayed his visa for something like 14 years.

Nancy Pelosi is of course a big fan of immigrants, and a big enemy of deporting illegal ones. She has made numerous maudlin statements about how wonderful and great illegal immigrants are, and how they enrich American society, and how it’s evil to suggest some might be criminals and, you know, go upside a senior citizen’s head with a ball peen hammer.

Further regarding the political angle here. It appears that the perp (David DePape) is yet another sad example of the epidemic of insane homeless/transient people that infest many American cities, and are a particular curse in the Bay Area. Again courtesy of leftist politicians of whom Nancy Pelosi is an avatar.

I think I remember hearing something a few years back about chickens coming home to roost. Well, here you go.

Also on the political implications of this, it has been revealed that the crack Capitol Police had Pelosi’s home under video surveillance . . . but just happened not to be paying attention when all this went down. Sort of like Epstein’s jailers, I guess.

The Capitol Police response is priceless. They regret the lapse and it is under investigation. But . . . never let a crisis go to waste! The head of the Capitol Police is using this as an opportunity to get more “resources“!

“We fucked up, so we need more money.”

That, ladies and gentlemen, is government in a nutshell.

So yes, there are many political implications of the Pelosi assault. It just so happens that none of them are the one that Hillary and other Democrats are pushing.

No doubt you find that shocking!

November 1, 2022

Gaslighting Squared

The frightening (in appearance and deed) NY governor Kathy Hochul has a novel explanation for her and her fellow Democrats’ unexpected political peril: Republicans are “master manipulators” who “have this conspiracy going all across America to try and convince people that in Democratic states they’re not as safe.” (Warning! Article contains a photo of Hochul! It did appear on Halloween, but still.)

In other words, Republicans are gaslighting Americans to believe–against the evidence of their own eyes–that crime has spiked in the US.

I have to say the Republicans, especially in places like New York, have given no evidence that they are in fact “master manipulators.” The last Republican governor of the Empire State left office 15 years ago. The last Republican senator departed 23 years ago. Eight out of 27 members of the NY Congressional delegation are Republican. Biden won 61 percent of the vote in 2020: Hillary won 59 percent in 2016.

Doesn’t sound like mastery to me!

The New York media–including the national media based there–are reliably left/Democrat. There is only one non-Democrat major media outlet in the state (the NY Post). So how are the Republicans convincing people that they aren’t safe?

In fact, the last major Republican figure in the state–Rudy Giuliani–won because of the last crime epidemic in New York. He was popular because he was instrumental in making New York relatively safe, in comparison with other cities, and in contrast with its recent history.

Kathy Hochul is thus engaged in gaslighting about gaslighting. In her desperation and her palpable panic that New Yorkers will indeed vote with the evidence before their eyes of New York’s crime relapse the only way that she can think of responding is to tell them is that it’s all in their heads, and that it was planted there by the Republicans. The same Republicans that have been political roadkill in New York–especially New York city–for decades.

It’s self-evidently absurd. And it’s hard to think of a more telling admission of the political bankruptcy of the Democratic Party, especially on the issue of crime .

October 28, 2022

Blowing Smoke About Diesel

There is a huge amount of hysteria going on about the diesel market. Tucker Carlson is prominent in flogging this as an impending disaster:

Thanks to the Biden administration’s religious war, this country is about to run out of diesel fuel.https://t.co/51oLY1LDak pic.twitter.com/mwuBQcLu5u

— Tucker Carlson (@TuckerCarlson) October 28, 2022

Like so much of Tucker these days, this is an exaggerated, bowdlerized, and politicized description of what is happening. There is a kernel of truth (more on this below) but it is obscured and distorted by the exaggerations.

First off, it is complete bollocks to say “in 25 days there will be no diesel.” Current inventories–stocks–are about equal to 25 days of consumption. But production continues, at a rate of about 4.8 million barrels per week. So, yes, if US refineries stopped producing right now, in 25 days the US would be out of diesel. But this isn’t France! US refineries will keep chugging along, operating close to capacity, supplying the diesel market.

Stocks v. flows, Tucker, stocks v. flows.

Yes, by historical standards, stocks are very low, although there have been other periods when inventories have been almost this low. But low stocks are not a sign of a broken market, or of impending doom.

Low stocks do happen and periodically should happen in a well-functioning market. That is, “stock outs” regularly occur in competitive markets, for good economic reasons.

Assume that stock outs never occurred. Well that would mean that something was produced but never consumed. That makes no economic sense.

The role of inventories is to buffer temporary (i.e., short term) supply and demand shocks. I emphasize temporary because as I show in my book on the economics of storage, storage is driven by scarcity today relative to expected scarcity in the future. A long term demand or supply shock affects current and expected future scarcity in the same way, and hence don’t trigger a storage response. In contrast, a temporary/transient shock (e.g., a refinery outage) affects current vs. future scarcity, and triggers a storage response.

For example, a refinery outage raises current scarcity relative to future scarcity. Drawing down on stocks mitigates this problem. For an opposite example, a temporary demand decline raises future scarcity relative to current scarcity. This can be mitigated by storage–reducing consumption some today in order to raise consumption in the future (when the good is relatively scarce).

To give some perspective on what “short term” means, in my book, I show that for the copper market inventory movements are driven by shocks with a half life of about a month.

Put differently, storage of a commodity (diesel, copper) is like saving for a rainy day. When it rains, you draw down on inventories. When it rains a lot for an extended period, you can draw inventories to very low levels.

And that’s basically what has happened in the diesel market.

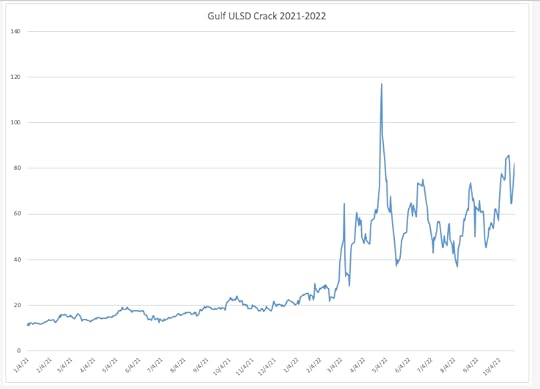

Carlson is right about one thing: the Russian invasion in Ukraine precipitated the situation. This is best seen by looking at diesel crack spreads–the difference between the value of a barrel of diesel (measured by the Gulf Coast price) and the value of a barrel of oil (measured by WTI):

Gulf Diesel-WTI Crack

Gulf Diesel-WTI CrackAlthough the crack was gradually increasing in 2021 (due to the rebound from COVID lockdowns) the spike up corresponds almost precisely with the Russian invasion. After reaching nosebleed levels in late-April, early-May, the crack declined to a still-historically high level and roughly plateaued over the summer, before beginning to widen again in September. This widening is in large part a seasonal phenomenon–heating oil (another middle distillate) demand picks up at that time.

In terms of storage, the initial market response made sense. The war was expected to be of relatively short duration. So draw down on inventories. However, the war has persisted longer than initial expectations, and the policy responses–notably restrictions on Russian exports, including refined products to Europe–have also taken on a semi-permanent cast. So the shock has endured far longer than expected, but the (rational) response of drawing down on stocks has left us in the current situation.

To extend the rainy day example, if you don’t expect it to rain 40 days and 40 nights (or for 9 months) you will draw down on inventories and you’ll go close to zero if the rain lasts longer than expected. That’s what we’ve seen in diesel.

As in any textbook stockout situation, price will adjust to match consumption with productive capacity. Inventories will not buffer subsequent supply and demand shocks, meaning that prices will be pretty volatile: storage dampens volatility.

I should note that low inventory levels can create opportunities for the exercise of market power–manipulations/corners/squeezes. So it is possible that some of the price and spread moves in benchmark prices may reflect more than these tight fundamentals.

Hopefully the hysteria will not trigger idiotic policy responses. The supply shock has been most acute in Europe (because it consumed a lot of Russian middle distillate). This has resulted in a substantial uptick in US exports (diesel and gasoline) to Europe, which has led to suggestions that the US restrict exports, or ban them altogether. This would be beggar–or bugger–thy neighbor, and would actually feed the recent narrative advanced by Manny Macron and others in Europe that the US is exploiting Europe’s energy distress.

Further, this would reduce the returns to refinery capital, reducing the incentive to invest in this sector–which would be a great way of perpetuating the current scarcity.

But this administration, and in particular its (empty) head, somehow think returns to capital are a bad thing:

This is throwing pearls before a swine, but here goes. Investment raises wealth and wages, and lowers prices. People invest only if they expect to earn a return. https://t.co/LjC2zdrlg4

— streetwiseprof (@streetwiseprof) October 28, 2022

Believe it or not, there are even worse proposals than export bans, windfall profits taxes, and restrictions on returning cash to investors bouncing around. In particular, supposedly serious people (who travel in the best of circles) like Columbia’s Jason Bordoff are suggesting nationalization of the US energy industry.

Yeah. That’ll fix things.

What we are seeing in diesel (and in other energy markets as well) is their efficient operation in the face of extreme supply and demand shocks. You may not like the message that prices and stocks are sending–that fundamental conditions are really tight–but suppressing those signals, or other types of intervention like export bans–will make the situation worse, not better.

And yes, energy market (and commodity market generally) conditions should definitely be considered when evaluating how to handle Russia and the war in Ukraine. But that evaluation is not advanced by hysterical statements about the nation grinding to a halt at Thanksgiving because we’ll be out of diesel.

October 17, 2022

Clearing Is Not A Harmless Bunny: I Told You That I Told You That I Told You [ad infinitum] That I Told You So

I have long called myself “the Clearing Cassandra” for my repeated and unheeded warnings about the dangers of letting the Trojan Horse of clearing (and the margining of uncleared trades) into the financial citadel. Specifically, clearing/margining can create financial shocks (and indeed financial crises) rather than preventing them (which is the supposed justification for mandating them).

We have seen several examples of this in the past several years, including the COVID (lockdown) shock of March 2020 (a subject of a JACF article of mine) and the recent energy market tremors. The most recent example, and in many ways the most telling one, is the recent instability in the UK that led the Bank of England to intervene to prevent a full-on crisis. The tumult fed a spike in UK government yields and contributed to a plunge in the Pound.

The instability was centered on UK pension funds engaged in a strategy called Liability Directed Investment (LDI)–which should now be renamed Liquidity Danger Investment. In a nutshell, in LDI defined benefit pension funds hedge the interest rate risk in their liabilities through interest rate swaps that are cleared or otherwise margined daily on a mark-to-market basis, rather than investing in fixed income securities that generate cash flows that match the liabilities. The funds hold non-fixed income assets (sometimes referred to as “growth assets”) in lieu of fixed income. (I discuss the whys of that portfolio strategy below.)

On a MTM basis, the funds are hedged: a rise in interest rates causes a decline in the present value of the liabilities, which matches a decline in the value of the swaps. Even if there is a duration match, however, there is not a liquidity match. A rise in interest rates generates no cash inflow on the liabilities (even though they have declined in value), but the clearing/margining of the swaps leads to a variation margin outflow: the funds have to stump up cash to meet VM obligations.

And this has happened in a big way due to interest rate increases driven by central bank tightening and the deteriorating fiscal situation in the UK (which has been exacerbated substantially by the energy situation, and the British government’s commitment to absorb a large fraction of energy costs). This led to big margin calls . . . which the funds did not have cash to cover. So, cue a fire sale: the funds dumped their most liquid assets–UK government gilts–which overwhelmed the risk bearing capacity/liquidity of that market, leading to a further spurt in interest rates . . . which led to more VM obligations. Etc., etc., etc.

In other words, a classic liquidity spiral.

The BofE intervened by buying gilts in massive amounts. This helped stem the spiral, though the problem was so acute that the BofE had to extend its purchases beyond the period it initially announced.

So yet again, central bank intervention was necessary to provide liquidity to put out fires created by margining.

FFS. When will people who should know better figure this out? How many times is it necessary to hit the mule upside the head with a 2×4?

I just returned from France, and while walking by the Banque de France I thought of a conference held there in the fall of 2013 at which I spoke: the conference was co-sponsored by the BdF, BofE, and ECB. It was intended to be a celebration of the passage and implementation of various post-Crisis regulations, clearing mandates most prominent among them.

I did my buzz kill Clearing Cassandra routine, in which I warned very specifically of the liquidity spiral dangers inherent in clearing as a source of financial instability. I got pretty much the same response as the Trojan Cassandra–a blow off, in other words. Indeed, I quite evidently got under some skins. The next speaker was Benoît Cœuré, a member of the ECB governing council. The first half of his talk was a very intemperate–and futile–attempt at rebuttal. Which I took as a compliment.

Alas, events have repeatedly rebutted Cœuré and Gensler and all the other myriad clearing cheerleaders.

The LDI episode has validated other arguments that I made starting in late-2008. Most notably, clearing was touted as a “no credit” system because the clearinghouse does not extend any credit to counterparties: variation margin/mark-to-market is the mechanism that limits CCP credit exposure. Since one (faulty) narrative of the Crisis was that it was the result of credit extended to derivatives counterparties, clearing was repeatedly touted as a way of reducing systemic risk.

Not so fast! I said. Such a view is profoundly unsystemic because it neglects the fact that market participants can substitute other forms of credit for the credit they no longer get via derivatives trades. And indeed, in the recent LDI episode exemplifies a very specific warning I made over a decade ago: those subject to clearing or margining mandates would borrow on the repo market to fund margin obligations, including both initial margin and variation margin.

And indeed the UK funds did exactly that. This actually increased the connectedness of the financial system (contrary to the triumphant assertions of Gensler and others), and this connectedness via the repo channel was another factor that drove the BofE to intervene.

My beard is not quite this long (though it’s getting there) but this is pretty much spot on:

Clearing is Not a Harmless Bunny

Again: Clearing converts credit risk into liquidity risk. And all financial crises are liquidity crises.

Maybe someday people will figure this out. Hopefully before I snuff it.

And the idiocy of this is especially great with respect to the UK pension funds because they posed relatively little credit risk in the first place. So there was not a substitution of one risk (liquidity risk) for another (credit risk). There was an addition of a new risk with little if any reduction of any other risk.

The LDI strategies were right way risks. Interest rate movements that cause swaps to lose value also increase the value of the funds (by reducing the PV of their liabilities). The funds were not–and are not-leveraged plays on interest rate risk. So the prospects of defaults on derivatives that could be mitigated by clearing were minimal.

Here I have to part ways with someone I usually agree with, John Cochrane, who characterizes the episode as another example of the dangers of leverage. He cites to a BofE document about the LDI episode that indeed mentions leverage, but the story it tells is not the classic lever-up-and-lose-more-when-the-market-moves-against-you one that John suggests. Instead, in figure in the BofE piece that John includes in one of his posts, the increase in interest rates actually makes the pension fund better off in present value terms–even including its LDI-related positions–because its assets go down less in value than its liabilities do. In that sense, the LDI positions are an interest rate hedge. But there is a mismatch in the liquidity impacts.*. It is this liquidity mismatch that causes the problem.

The BofE piece also suggests that the underlying issue here is pension fund underfunding. In essence, the pension funds needed to jack up returns to close their funding gap. So instead of investing in fixed income assets with cash flows that mirrored those of its pension liabilities, the funds invested in higher returning assets like equities. Just investing in fixed income would have locked in the funding gap: investing in equities increased the odds of becoming fully funded. But just investing in equities alone would have subjected the funds to substantial interest rate risk. So the LDI strategies were intended to immunize them against this risk.

Thus, the original sin was the underfunding. LDI was/is not a way of adding interest rate risk through leverage to raise expected returns to close the gap (gambling on interest rate risk for resurrection). Instead it was a way of managing interest rate risk to permit raising returns to close the gap by changing portfolio composition. (No doubt regulators were cool with this because it reduced the probability that pension fund bailouts would be needed, or at least kicked that can down the road, a la US S&L regulators in the 1980s.)

No, the real story here is not the oft-told tale of highly leveraged intermediaries coming to grief when their speculations turn out wrong. Instead, it is a story of how mechanisms intended to limit leverage directly lead to indirect increases in debt and more importantly to increases in liquidity risks. In that way, margining increases systemic risk, rather than reducing it as advertised.

*The BofE document describes an LDI mechanism that is somewhat different than using swaps to manage interest rate risk. Instead, it describes a mechanism whereby positions in gilts are partially funded by repo borrowing. The borrowing is necessary to create a position large enough to create enough duration to match the duration of a fund’s liabilities. But a swap is economically equivalent to a position in the underlying funded by borrowing, so the difference is more apparent than real. Moreover, the liquidity implications of the interest rate hedging mechanism in the BofE document are quite similar to those of a swap.

October 1, 2022

Another Anti-Anglo Saxon Jeremiad From a Demented (and Desperate) Dwarf

In an earlier post I said that Putin’s mobilization address was his most unhinged speech ever. That record did not last long: his Friday speech announcing the annexation of four Ukrainian regions was beyond unhinged.

The speech was Castroesque in length. The bulk of it was a jeremiad against the west, and “Anglo-Saxons” in particular. (Apparently he is unaware of American diversity!) He justified his invasion of Ukraine, and the annexations, as a war of survival against a west that is hell bent on subjugating Russia. The speech was a litany of the west’s sins, colonialism and slavery most prominent among them. He conveniently elided over Russia’s imperialism, symbolized today by the disproportionate representation of ethnic groups from Russian republics in those fighting–and dying–in Ukraine, and touted the USSR’s “anti-colonial” record in Africa and elsewhere.

The speech was chock-full of projection, most importantly regarding waging war on civilian populations. There were also the now familiar accusations of Ukrainian Naziism, the betrayal of 1991, and the non-existence of Ukrainian nationhood.

In brief, Putin portrayed the war in Ukraine as an existential conflict waged to defend Russia against Anglo-Saxons attempting to colonize Russia, and to defend the world against such western rapacity. (The reference to the Opium Wars was obviously an attempt to appeal to China, whose ardor for this Ukrainian adventure is obviously waning fast.)

The atmospherics were also bizarre. The images of a dwarfish Putin clasping hands with the hulking mouth breathers leading the sham annexed regions, chanting “Ross-i-ya!” with a demented grin on his face are quite striking–and disturbing. Especially when contrasted to the reality on the ground, where Russian forces continue to reel and rout–the bugout from Izyum being the latest example. “Reservists” are being shoved to the front without even a simulacrum of training, where they will no doubt be slaughtered without changing the battlefield dynamic one iota. Putin is giving no retreat orders and is bossing about formations that have been destroyed or dissolved. Gee, whom does that remind one of?

Tens of thousands of Russian men are fleeing to avoid the press gangs, a visible demonstration of widespread panic. (Kazakhstan–the Russian Canada!) Personal contacts indicate that the panic is widespread even among those who have not fled, but who fear the knock on the door.

The realities of the battlefield and the home front reveal that this is truly an existential conflict–for Putin. He objectively can’t win, but he can’t lose and survive. This creates a tremendous bias towards escalation, with nuclear weapons being his only real escalation option.

There is a considerable debate over whether when push comes to shove Putin will push the button. This is an unanswerable question. Suffice it to say that his Downfall-esque rants in public (one can only imagine what he’s like in private) mean that there is a material probability that he will.

Which poses a grave dilemma to the Anglo-Saxons. (In this respect, Putin is on to something: the continentals are hopelessly ineffectual and along for the ride.) Months ago I wrote that Putin was in zugzwang, i.e., a situation where any move made the situation worse, but one is compelled to move. Well, currently the US is arguably in zugzwang as well. The consequences of letting Putin off the hook or pushing him to the wall are both deeply unsatisfactory.

What is in the US’s opportunity set? The situation on the battlefield does suggest that giving Ukraine a blank weapons check could result in pushing Russia out of most of, and perhaps all, of the occupied portions of the country–including Crimea. But choosing that option is a bet on Putin’s sanity and willingness to go nuclear, and how far up the escalation ladder Putin is willing to go. Conversely, pulling the Ukrainian’s leash will likely result in a continued grinding war with its global and human and economic toll. Brokering a compromise is almost certainly out of the question, given the intransigence of the parties and the completely irreconcilable nature of their demands (though Putin did graciously say that he was willing to accept Ukraine’s capitulation).

The administration is clearly leaning towards–but not completely towards–engineering Russian defeat on the battlefield. Most of the American populace is disengaged. The populist right in the US is engaged but stupidly pro-Russian, because (a) Putin criticized the west’s trans obsession, and (b) the enemy of their enemy (the administration) is their friend. With respect to (a) this is beyond bizarre because these passing references were embedded in a speech that damned the entirety of American history in a way that would make Howard Zinn beam: is the PR buying into that now? (It is also stupid because it validates left narratives about them being Russian puppets.)

The populist right also immediately concluded that the US is responsible for the destruction of the Nord Stream I and II pipelines under the Baltic. The fact is we have no facts, other than that the pipelines suffered catastrophic ruptures, possibly the result of deliberate sabotage. Everything else you read is speculation about motive, which only prove whom the speculators hate most. Those who know ain’t talking, and those talking don’t know.

Although I immediately concluded sabotage, there is reason to doubt this too. This is plausible to me, based on my knowledge of natural gas pipelines and Russian incompetence. (Anybody remember the shitshow of the Russian oil pipelines in spring 2019?)

But again–nobody knows nothing beyond the fact that the pipelines are fucked, so speculation is pointless. And depressingly, given the natures of everyone involved, I can’t say there’s anyone I would trust to reveal the facts.

The populist right is annoying, but largely powerless. Even if the Republicans prevail in the upcoming election, the PR will represent a clamorous but ultimately irrelevant force. Meaning that the US will continue to stumble along, mainly in the direction of pushing an increasingly desperate Putin.

Yes, I can see the upside of that. But I also see considerable downside risk, and indeed the risks are asymmetric. Even as things stand now, beyond nuclear weapons Russia’s military capability has proven even more illusory than a Potemkin village of legend. His conventional threat to Nato is demonstrably non-existent. So the upside to the US and Nato of drubbing Putin further is very limited. But the downside of drubbing him could be serious indeed.

So mutual zugzwang is a not unrealistic description of the current situation.

September 24, 2022

Vova Shovels Fleas

In an unhinged speech earlier this week, Vladimir Putin (a) threatened (again) to use nukes, and (b) announced the mobilization of 300,000 reservists–although there are reports that the order actually calls for the mobilization of 1 million. This raises the issues of what this means about the state of the war, and the effect that the mobilization will have on it.

The speech speaks volumes about the state of the war. Putin realizes that he is losing, badly, and is desperate to reverse the reverses. He is in essence following Eisenhower’s advice: “Whenever I run into a problem I can’t solve, I always make it bigger. I can never solve it by trying to make it smaller, but if I make it big enough, I can begin to see the outlines of a solution.” Or, as it is often expressed: when a problem appears insoluble, enlarge it.

Putin has two margins on which he can enlarge: nukes and bodies. He’s threatening the former and implementing the latter.

When I say Putin’s speech was unhinged, I do not exaggerate. Look at the videos. He was incandescently angry. His rhetoric recycled the common themes–Nazis, Banderaists–and added twists on his West-directed paranoia by way of rationalizing (although not admitting) the defeats: Ukrainian forces are not just armed by the West, but Nato generals are in command and western troops are in the ranks. The speech was filled with projection about violations of sovereign territory and atrocities. Perhaps it was all for effect–Mad Vlad–to make the nuclear threats more credible. But it seems all too genuine to me.

As for the effect of the mobilization, a quote from Lincoln comes to mind: “Sending armies to McClellan is like shoveling fleas across a barnyard: not half of them get there.” My surmise is that far less than half the fleas that Putin is madly trying to shovel into Ukraine will get there.

If the front line Russian military has proved shambolic on the Ukrainian steppes, the Russian reserve system is beyond shambolic. It was allowed to decay after the collapse of the USSR (which depended on mass mobilization), and the military “reforms” of the last decade only accelerated its decay: the goal of the “reforms” (which were realized more in the promise than the delivery) was to move away from conscription-based forces towards a professional military.

It is therefore best to view what is happening not as a mobilization of an existing reserve force (e.g., the mobilizations seen in August 1914) but as an improvised, hurried mass conscription. Although the initial announcements stated that the mobilization would be targeted at those with combat experience and with specialized military skills, there are reports–all too believable–that the authorities are casting their net far beyond these categories, and that the unfortunates caught up in it are being assigned to units willy-nilly with no regard to their past duties. Tellingly, the dragnet is most intense in the republics: ethnic minorities have already borne the brunt of the war, and Putin wants to shelter metropolitan Russia as much as possible for fear of sparking unrest in the cities.

The existing Russian conscription system is a disaster, rife with evasion and corruption. And that was just to escape the miseries of peacetime service. Both will be far worse when the prospect is being shoveled to Donbas.

No this is not a mobilization. It is press ganging and the yield will be far less than Putin wants.

And what will be the effectiveness those poor fleas who do make it across the barnyard? More bodies will not fix the deep dysfunctions that have been revealed on the battlefield. The high command will still prove to be incompetent. Already poor leadership at the regimental, battalion, company, and platoon level will become even worse as poorly trained and dispirited officers will be put in charge of scared and resentful losers of the conscription lottery. Further, there will be an adverse selection problem: the cleverer and more fit will find ways to escape the net, leaving a disproportionately dimwitted, sociopathic, and addicted rump to fight. More bodies will not fix the paralyzing over-centralization of the Russian command. More bodies will not fix Russia’s disastrous logistics: indeed, trying to supply more bodies will actually exacerbate the logistical problems. More bodies will not fix Russia’s underperforming air forces. More bodies are not the same as more precision guided munitions. Historically Russia has used more bodies successfully when supported by massive artillery, but now ammunition shortages (is another “Shell Crisis” a la 1915 coming?) loom and Ukrainian counterbattery fire has proved devastating thanks to HIMARS and M177s. More bodies will not address Russia’s repeated intelligence failures at the operational or tactical levels. Russian armor has proved extremely vulnerable, but the more bodies will deploy in older and even less well-maintained AFVs.

In sum, more bodies cannot and will not fix the real reasons for Russian battlefield disasters. They will just be more victims for these reasons.

There is also the issue of how the new bodies will be deployed: as replacements or in entire units. The time involved in standing up new units is considerable, even if rushed. Putin is in a hurry, so I conjecture that the unfortunates swept up by the press ganskis will receive lick-and-a-promise “training” of a few weeks (after all, they are veterans, right?, so they just need a refresher course!) and be shoveled to the front and shoved into shattered units. If you look at say the American army in WWII, you’ll find that the life expectancy of replacements is often measured in hours or a few days. (Experienced infantrymen often avoided learning the names of replacements, because it was pointless.) That will happen here as well.

Historically, Russia relied on a huge demographic advantage vis a vis its foes in a quantity-over-quality approach. But even when Russia did have a demographic advantage, the results were often disastrous: cf. the Russo-Japanese War, and Tannenberg and other WWI battles. Now a demographically devastated Russia is falling back on old formulae. To call it tragic is an understatement.

In sum, more cannon fodder without more cannon (and logistics, and leadership, and on and on) to support them will result in a bloody disaster. But it will allow Putin to defer deciding whether to resort to his only other option: nukes.

It is also important to consider how Putin’s adversaries–not just Ukraine, but the US and the rest of Nato–will respond. The prospect of facing greater numbers (even of a low quality) incentivizes Ukraine to accelerate its offensives and press its advantages, even though that will entail larger losses. If successful, that would in turn accelerate when Putin has to decide whether to back down or resort to his only remaining way of expanding the problem. Ukraine will redouble its already frenzied efforts to lobby western governments for more weapons.

The US and Nato need to turn their attention from what is happening on the battlefield to focus intensely on forestalling Putin concluding that it’s nukes or nothing. Sadly, that means hoping that Putin’s more bodies measure will extend the stalemate, thereby buying time for some diplomatic resolution.

Alas, the US and its allies appear set on Ukrainian victory on the battlefield and on the humiliation of Putin, rather than on securing an unsatisfying and messy diplomatic compromise. That is gambling with millions of lives–and perhaps many more.

Which means that where things go may hinge crucially on the Russian popular reaction to Putin’s desperate measure. It is optimistic in the extreme to believe that the mobilization will spur a 1905 or February 1917 or August 1991 moment in Russia. And it is equally optimistic to believe that if such a moment indeed occurs, that it will not result in Putin’s replacement with someone even worse.

Craig Pirrong's Blog

- Craig Pirrong's profile

- 2 followers