Christopher Sprigman's Blog, page 8

October 11, 2012

Shanzhai in Shanghai

I just returned from Shanghai Tuesday night, and while the trip had many great aspects, the one that was especially interesting for this blog was how knockoffs were sold. Near some of the major tourist attractions, like the City God Temple, nearly all the tourists were Chinese. (It was the end of the “Autumn Moon” holiday.) But when my wife and I were spotted by a seller, we were quickly shown a folded flier with photos of knockoff watches and handbags. What was most interesting was that all over Shanghai, every seller seemed to have the identical flier with identical pics–in other words, a standardized system of knockoff advertising.

I just returned from Shanghai Tuesday night, and while the trip had many great aspects, the one that was especially interesting for this blog was how knockoffs were sold. Near some of the major tourist attractions, like the City God Temple, nearly all the tourists were Chinese. (It was the end of the “Autumn Moon” holiday.) But when my wife and I were spotted by a seller, we were quickly shown a folded flier with photos of knockoff watches and handbags. What was most interesting was that all over Shanghai, every seller seemed to have the identical flier with identical pics–in other words, a standardized system of knockoff advertising.

The other interesting thing I learned was why the lines for major Western luxury goods stores, like Chanel, are so long in Hong Kong. It’s not just about the love of conspicuous consumption–though I heard many stories in Hong Kong about Chinese mainlanders coming in and buying whatever was the most expensive item in the store. In Shanghai, the same stores exist but there are no lines to get in and no velvet ropes outside to contain the crowds. The reason is that taxes are much lower in Hong Kong. Newly-minted Chinese millionaires may love to show off the most expensive Western brands, but they still try to pay as little as they can. No surprise there.

October 10, 2012

The Federal Trade Commission investigates Google’s use of patents

Federal Trade Commission headquarters, DC

News in today’s NY Times that the Federal Trade Commission has opened an antitrust investigation into Google’s use of “standards essential patents” — i.e., patents that are necessary to the basic operation of smartphones and tablet computers. Google has represented to standards setting organizations (private industry groups that define and adopt rules meant to allow devices from different manufacturers to work together on a common standard) that if standards were adopted that would require smartphone and tablet makers to use its patents, that it would license them on “fair, reasonable, and non-discriminatory” terms. Many standard setting organizations require this sort of “FRAND” licensing commitment as a condition of participation in the standard setting process. In any event, the article suggests that the FTC is investigating to see whether Google is living up to these commitments, or whether they are using their standards essential patents to disadvantage rivals.

This is an important issue. Abuse of standards essential patents can harm competition. And the FTC is well aware of that fact. In Senate testimony in July, Edith Ramirez, an F.T.C. commissioner, speaking of the potential abuse of standard-essential patents, said, “Holdup and the threat of holdup can deter innovation by increasing costs and uncertainty for other industry participants, including other patent holders.”

Stay tuned.

October 9, 2012

The NY Post on fast fashion and knockoffs

The NY Post has a quick and fun article about fast fashion and knockoffs. Giant fast fashion retailers like H&M, Topshop, and Zara make designer looks available to women who could never afford the real thing. Indeed, as the article says, in some cases the fast fashion stores knock off designer apparel that never made it from the runway to the shops — they are, in effect, making a bet on designs the originator left on the cutting room floor. And this is all perfectly legal — U.S. copyright law doesn’t apply to fashion design. That keeps fashion innovative, relevant, and — most importantly — democratic. Who wants to live in a world where only the rich can look good?

The NY Post has a quick and fun article about fast fashion and knockoffs. Giant fast fashion retailers like H&M, Topshop, and Zara make designer looks available to women who could never afford the real thing. Indeed, as the article says, in some cases the fast fashion stores knock off designer apparel that never made it from the runway to the shops — they are, in effect, making a bet on designs the originator left on the cutting room floor. And this is all perfectly legal — U.S. copyright law doesn’t apply to fashion design. That keeps fashion innovative, relevant, and — most importantly — democratic. Who wants to live in a world where only the rich can look good?

W.H. Auden and the patent system

From today’s NY Times Bits Blog, a short follow-up on Monday’s long article on the dysfunctions of the patent system. Today’s entry briefly tells the story of Apple’s early-1980′s patent entanglement with IBM, the then-dominant computer maker. IBM had a stack of PC-related patents, and it was using them partly to collect licensing fees, but mostly to fence out competitors. Big Blue brandished their patents against Apple and demanded licensing fees. But in the negotiations that followed, it emerged that IBM was concerned in particular that Apple not be competing against it in the mainframe computer business. As a condition of the patent license, IBM demanded that Apple never manufacture a computer larger than a government worker’s desk.

From today’s NY Times Bits Blog, a short follow-up on Monday’s long article on the dysfunctions of the patent system. Today’s entry briefly tells the story of Apple’s early-1980′s patent entanglement with IBM, the then-dominant computer maker. IBM had a stack of PC-related patents, and it was using them partly to collect licensing fees, but mostly to fence out competitors. Big Blue brandished their patents against Apple and demanded licensing fees. But in the negotiations that followed, it emerged that IBM was concerned in particular that Apple not be competing against it in the mainframe computer business. As a condition of the patent license, IBM demanded that Apple never manufacture a computer larger than a government worker’s desk.

I’m surprised that the Apple people didn’t burst out laughing. In any event, the IBM threats apparently left an impression — Apple learned that if you aren’t a patent aggressor, you might be a patent victim. And that reminds me of this famous and wonderful bit by Auden:

“I and the public know

What all schoolchildren learn,

Those to whom evil is done

Do evil in return.”

October 8, 2012

The (Over-)Optimism of Creators

We have a new post up on the Psychology Today blog detailing two laboratory studies by one of us (Sprigman) along with Christopher Buccafusco of the Chicago-Kent College of Law. The studies show that creators tend to be markedly over-optimistic about the market propects of their work. Which means, in turn, that they tend to over-value their work. This overvaluation makes transactions in creative works more difficult. But it also makes creativity more robust — even in the face of expected losses from piracy. So, good news and bad news, I suppose. But interesting either way.

We have a new post up on the Psychology Today blog detailing two laboratory studies by one of us (Sprigman) along with Christopher Buccafusco of the Chicago-Kent College of Law. The studies show that creators tend to be markedly over-optimistic about the market propects of their work. Which means, in turn, that they tend to over-value their work. This overvaluation makes transactions in creative works more difficult. But it also makes creativity more robust — even in the face of expected losses from piracy. So, good news and bad news, I suppose. But interesting either way.

The Knockoff Economy on Bloomberg Law: Software Patents Last Too Long

Josh Block of Bloomberg Law has just released a second video based on his interview with me (Sprigman). In this installment, Josh asks me about the changes that I’d like to see in copyright and patent law.

Josh Block of Bloomberg Law has just released a second video based on his interview with me (Sprigman). In this installment, Josh asks me about the changes that I’d like to see in copyright and patent law.

Note: With respect to possible changes in the law, I’m speaking only for myself, and not for Kal.

NY Times on the patent wars

The NY Times runs a lengthy and (mostly) well-sourced article, with graphics, on how firms in various industries use patents to bully rivals and suppress innovation. The dark side of the patent system is getting more and more attention since the Apple/Samsung verdict. Here are a few central grafs that convey the article’s overall tone:

The NY Times runs a lengthy and (mostly) well-sourced article, with graphics, on how firms in various industries use patents to bully rivals and suppress innovation. The dark side of the patent system is getting more and more attention since the Apple/Samsung verdict. Here are a few central grafs that convey the article’s overall tone:

“In the smartphone industry alone, according to a Stanford University analysis, as much as $20 billion was spent on patent litigation and patent purchases in the last two years — an amount equal to eight Mars rover missions. Last year, for the first time, spending by Apple and Google on patent lawsuits and unusually big-dollar patent purchases exceeded spending on research and development of new products, according to public filings.

Patents are vitally important to protecting intellectual property. Plenty of creativity occurs within the technology industry, and without patents, executives say they could never justify spending fortunes on new products. And academics say that some aspects of the patent system, like protections for pharmaceuticals, often function smoothly.

However, many people argue that the nation’s patent rules, intended for a mechanical world, are inadequate in today’s digital marketplace. Unlike patents for new drug formulas, patents on software often effectively grant ownership of concepts, rather than tangible creations. Today, the patent office routinely approves patents that describe vague algorithms or business methods, like a software system for calculating online prices, without patent examiners demanding specifics about how those calculations occur or how the software operates.

As a result, some patents are so broad that they allow patent holders to claim sweeping ownership of seemingly unrelated products built by others. Often, companies are sued for violating patents they never knew existed or never dreamed might apply to their creations, at a cost shouldered by consumers in the form of higher prices and fewer choices.”

October 4, 2012

An important new academic paper calls for the abolition of patents

Prominent Washington University (St. Louis) Economists Michele Boldrin (left) and David Levine (below, shown receiving an academic medal) have released a new, short, and extremely hard-hitting paper, titled The Case Against Patents. You can download it for free here.

Prominent Washington University (St. Louis) Economists Michele Boldrin (left) and David Levine (below, shown receiving an academic medal) have released a new, short, and extremely hard-hitting paper, titled The Case Against Patents. You can download it for free here.

In the paper, Boldrin and Levine mount a full-scale frontal assault on the current American patent system. They say that there is no empirical evidence to suggest that strong patent protection increases innovation or productivity. But there is evidence, the authors argue, that patents have a host of negative consequences. Stagnant industries and firms use patent lawsuits to squash innovative upstarts. The proliferation of patent rights creates wasteful “arms races” as companies divert resources away from innovation and toward patenting (in order not to be out-gunned by rivals with big patent portfolios), which leads to “thickets” of overlapping patent claims that makes deploying new technologies without fear of liability exceedingly difficult. And the lure of patent protection lets loose a flood of lobbying, as incumbents seek new rules protecting them from more innovative rivals. Boldrin and Levine are particularly cutting when they describe what this incessant pro-patent lobbying has done to suppress innovation.

“It should be clear, then, that given this set of players and their incentives, the patent game can have only one equilibrium over time, which is the one we have observed. Starting from a regime of intellectual property protection that, about two centuries back, was restricted in its areas of applicability and limited in both depth and duration over time – that is to say: it was somewhat “reasonable” to the extent it balanced social gains and social costs – we have witnessed a monotone process of progressive enlargement and strengthening of patent laws. At each stage of this process of enlargement the main driving force were the rent-seeking efforts of large, cash-rich companies unable to keep up with new and creative competitors. Patent lawyers, patent officials and wannabe patent trolls usually acted as foot soldiers. While this political economy process is theoretically pretty straightforward – especially because it closely replicates similar experiences in other fields of regulation and, especially, in the development of barriers to free trade – what is still missing is an empirical, quantitative analysis of the stakes involved and of the gains and losses accruing to both the active players and to the rest of society, from the general public to the innovators that, because of IP, never were.

The solution? Boldrin and Levine wants patent law abolished. Indeed, they want an amendment to the U.S. Constitution to make sure that the monster, once killed, can never rise from its grave.

We should be clear on the relationship of Boldrin and Levine’s work to our own. We don’t go nearly as far in The Knockoff Economy as Boldrin and Levine do in this paper. We aren’t calling for patent (or copyright) to be abolished. But our work is, in an important sense, complementary to Boldrin and Levine’s. They say that there is no evidence that strong patent protection sparks innovation. Our book looks at a group of industries which lack strong patent and copyright protection, and we observe that there is plenty of innovation anyway. We’re taking on the same problem, from different directions. And, of course, we’re more circumspect in what we’re advocating. But no matter: the Boldrin and Levine paper is worth your attention.

October 3, 2012

Richard Posner: many creative industries don’t need patent or copyright

We couldn’t have said it better ourselves.

We couldn’t have said it better ourselves.

Richard Posner, one of the leading intellectuals on the federal bench, has been speaking out a lot lately on the patent and copyright laws — suggesting that they’ve both (especially patent) gotten out of control and need to be reined in. And now Posner has launched his latest salvo on the blog he co-authors with Nobel prize-winning economist Gary Becker. In a lengthy but very readable post, Posner argues that we have much more of both patent and copyright than we need. The same patent rights that make good sense for the pharmaceutical industry, Posner writes, are useless and even mischievous when applied to other industries, such as software. And many of the arguments that Posner employs echo what we say in The Knockoff Economy:

Pharmaceutical drugs are the poster child for patent protection. Few other products have the characteristics that make patent protection indispensable to the pharmaceutical industry. Most inventions are inexpensive, and even without patent protection, or any other legal protection from competition, the first firm to invent a product usually has significant protection from competition in the near term. The first firm gets a headstart on moving down his cost curve as experience demonstrates ways of cutting costs and improving the product. And the public is likely to identify his brand with the product, and keep buying it even after there is competition, and at a premium price. Moreover, many new products have only a short expected life, so that having 20 years of patent protection would confer no real benefit—except to enable the producer to extract license fees from firms wanting to make a different product that incorporates his invention.

Nor does copyright escape Posner’s ire:

The most serious problem with copyright law is the length of copyright protection, which for most works is now from the creation of the work to 70 years after the author’s death. Apart from the fact that the present value of income received so far in the future is negligible, obtaining copyright licenses on very old works is difficult because not only is the author in all likelihood dead, but his heirs or other owners of the copyright may be difficult or even impossible to identify or find. The copyright term should be shorter.

There’s a lot here, and we urge you to read all of it. But even if we differ with Posner on a few specifics, we find ourselves agreeing with his conclusion: that for a lot of creative industries, copyright and patent aren’t necessary to provoke innovation, and that sometimes the law does best by staying out.

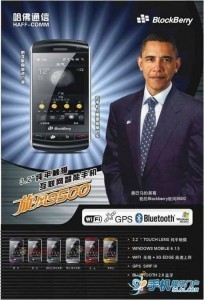

Obama and the Blockberry

I’m leaving tomorrow for Shanghai for a few days, where I will attend a conference at Fudan University and talk about knockoffs.

But as we’ve noted before, this is a little like talking about coal in Newcastle. China is the global center of copying, and its unique “shanzhai” culture is worth more exploration. I’m looking forward to bringing back some great photos, like this one.