Christopher Sprigman's Blog, page 4

November 21, 2012

High Art

One of the bigger copyright cases recently is Kirtsaeng v. John Wiley & Sons, argued this fall before the Supreme Court. The case is about reselling textbooks bought abroad, but it has much larger implications. The New York Observer discusses the possible effects on museums, which frequently traffic in goods produced (and purchased) abroad:

Unlike many of the city’s galleries, New York’s museums made it out of Hurricane Sandy relatively unscathed. But even as the storm raged, they were quietly facing another battle— in court.

Blockbuster exhibitions like the Guggenheim’s “Picasso Black and White,” the Whitney’s “Yayoi Kusama” and the Met’s “The Steins Collect” could be a thing of the past if a decision in a lower-court case involving textbook sales is upheld by the Supreme Court. On Oct. 29, the court, which was open despite the hurricane, heard oral arguments in Kirtsaeng v. John Wiley & Sons, a legal battle over whether copyrighted books produced abroad can be imported to the U.S. and resold. Though the case involves textbooks, it also implicates a section of the copyright law that applies to Picassos and Brancusis. The case started out in 2008 in federal district court in New York. Supap Kirtsaeng, a foreign exchange student at Cornell, found that his textbooks could be purchased more cheaply in his native Thailand, so he asked friends to buy the books there and ship them to New York. He then started selling them on eBay and, when he had racked up $37,000 from those sales, the textbooks’ publishers, John Wiley & Sons, filed suit. Mr. Kirtsaeng was found guilty of willful infringement and was asked to pay $75,000 for each of the eight Wiley textbooks he sold copies of, for a total of $600,000. Mr. Kirtsaeng appealed that decision, and in August 2011, the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit found him guilty as well. In the meantime, in July 2012, the Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD) and a group of 28 American museums including the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, The J. Paul Getty Trust, the Museum of Modern Art and the Whitney filed a brief as “friends of the court,” in support of Mr. Kirtsaeng.

Mr. Kirtsaeng’s attorneys invoked the “first sale doctrine,” which can be found in section 109(a) of the Copyright Act, which limits certain rights of the copyright owner. The doctrine enables an owner of a copy to buy, sell, loan or borrow it without getting the permission of the copyright owner. (A “copy” under the Copyright Act doesn’t mean a pirated work or a work that is not original; it means the material object in which the copyrighted work is first fixed—so a copy could be an original work like a Damien Hirst shark sculpture, or it could refer to any of the millions of paperbacks of Fifty Shades of Grey published by Vintage.) But John Wiley & Sons, the publisher, maintains that the doctrine does not apply to works made abroad.

While this case turns on section 109(a) of the statute, which allows the owner of a “lawfully made” copy to resell it, the same language appears in another section, 109(c), which allows the owner of a “lawfully made” copy to display it—and has for years been giving museums the right to show the artworks that they buy and borrow.

“Art museums have long depended on Section 109 of the Copyright Act,” the brief states, “to develop and display their permanent collections and to assemble and present special exhibitions of art … without having to obtain the copyright owner’s permission.” Displaying, acquiring, borrowing and loaning art are at the core of what museums do.

November 20, 2012

Natural Born Killer

[image error]

Tattoos are increasingly cropping up in lawsuits about copying. Mike Tyson’s facial tattoo, famously highlighted in The Hangover 2, is one well-known example.

Recently another fighter’s tattoo is embroiled in a dispute over rights over copying. Carlos Condit, the Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) welterweight champ, is known as The Natural Born Killer. His tattoo, inked by a guy named Chris Escobedo, appears–along with the rest of Condit–in a new video game called UFC Undisputed 3. Escobedo is suing, claiming that he owns the copyright in the tattoo and while he “implicitly licensed” Condit to display it in actual fights, he never gave anyone–either Condit or THQ, the game maker–the right to recreate it digitally for a video game. For the full complaint, go here.

November 19, 2012

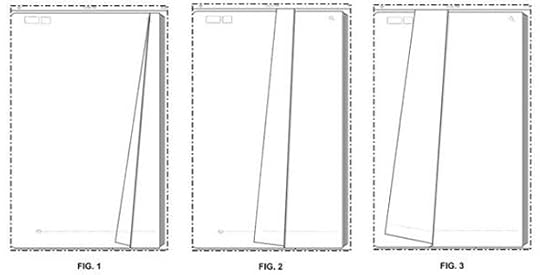

Apple Now Owns the Page Turn

The New York Times Bits Blog has a post on the latest dubious design patent Apple has secured. Design patents are not a bad idea in the abstract, and they can play an important role in design innovation. But too often these patents simply give firms exclusive rights over simple and obvious designs, allowing them to wield the “patent” as a cudgel against competitors. As the Times writes:

If you want to know just how broken the patent system is, just look at patent D670,713, filed by Apple and approved this week by the United States Patent Office.

This design patent, titled, “Display screen or portion thereof with animated graphical user interface,” gives Apple the exclusive rights to the page turn in an e-reader application.

Yes, that’s right. Apple now owns the page turn. You know, as when you turn a page with your hand. An “interface” that has been around for hundreds of years in physical form. I swear I’ve seen similar animation in Disney or Warner Brothers cartoons.

(This is where readers are probably checking the URL of this article to make sure it’s The New York Times and not The Onion.)

The Times Bits Blog goes to describe some of the detail of the patent. And it puts the patent in context:

Of course this isn’t the most seemingly obvious patent Apple has been awarded in recent years. The company has also been granted patents for an icon for music (which is a just a musical note), the glass staircase used in the company’s stores – yes, stairs, that people walk up — and for the packaging of its iPhone.

Will libertarians jump ship on copyright?

Jerry Brito, a senior research fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University and the director of GMU’s technology policy program, has alerted us to a new book which, we suspect, might be at the leading edge of a trend. First, here’s a link to the book, which is called “Copyright Unbalanced: From Incentive to Excess.” You get a sense of the book’s perspective from the title — the argument is that copyright has in effect become just another arm of big government . . . a system that no longer functions as an effective incentive to creative labor, but instead increasingly interferes with personal liberty, suppresses speech, and enriches government’s cronies at the public’s expense. What makes this book especially noteworthy is the impressive roster of libertarians who are interested in copyright, and are not particularly fond of it, including the National Review’s Reihan Salam, GOP strategist Patrick Ruffini, and the Cato Institute’s Tim Lee.

Jerry Brito, a senior research fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University and the director of GMU’s technology policy program, has alerted us to a new book which, we suspect, might be at the leading edge of a trend. First, here’s a link to the book, which is called “Copyright Unbalanced: From Incentive to Excess.” You get a sense of the book’s perspective from the title — the argument is that copyright has in effect become just another arm of big government . . . a system that no longer functions as an effective incentive to creative labor, but instead increasingly interferes with personal liberty, suppresses speech, and enriches government’s cronies at the public’s expense. What makes this book especially noteworthy is the impressive roster of libertarians who are interested in copyright, and are not particularly fond of it, including the National Review’s Reihan Salam, GOP strategist Patrick Ruffini, and the Cato Institute’s Tim Lee.

“Copyright Unbalanced” suggests to us that anti-copyright arguments are gaining ground among conservatives and libertarians. We wrote recently of the possibility that copyright policy could become a partisan issue — with the GOP moving away from support for ever-expanding copyright, and the Democrats left as the party supporting increasingly harsh laws. Why? Two reasons. First, because the entertainment industries heavily favor the Democrats, and the GOP has less to lose from taking a stand in favor of more carefully balancing copyright with the interests of users. Second, because the GOP might actually have something to gain. The libertarian wing of the GOP is the most intellectually vibrant part of the party, and tech-friendly libertarians are increasingly questioning the strength of copyright’s economic logic and noting that copyright law often favors the interests of old, boring incumbent firms against inventive start-ups.

A few days after our piece on the changing politics of copyright, the Republican Study Committee (a group of conservative GOP House members) put out a document sharply criticizing current copyright law and calling for deep reforms. That was on a Friday, but by Sunday, after what we imagine were some furious phone calls from entertainment industry lobbyists, the RSC report was withdrawn.

So here’s another prediction: this genie isn’t going back into the bottle so easily. The arguments against over-broad copyright are out there in the libertarian and conservative ecosystem, and they are spreading. Some smart GOP strategist, somewhere, is mulling over whether taking a stand in favor of more balanced copyright is a good way for the GOP to appeal to younger voters, who spurned the party this November. We’ll be hearing more about this.

November 18, 2012

Head Scratching at the GOP

Techdirt on how Republicans in Congress are tying themselves in knots over copyright policy. An amazing story:

So, late Friday, we reported on how the Republican Study Committee (the conservative caucus of House Republicans) had put out a surprisingly awesome report about copyright reform. You can read that post to see the details. The report had been fully vetted and reviewed by the RSC before it was released. However, as soon as it was published, the MPAA and RIAA apparently went ballistic and hit the phones hard, demanding that the RSC take down the report. They succeeded. Even though the report had been fully vetted and approved by the RSC, executive director Paul S. Teller has now retracted it, sending out the following email to a wide list of folks this afternoon:

From: Teller, Paul

Sent: Saturday, November 17, 2012 04:11 PM

Subject: RSC Copyright PB

We at the RSC take pride in providing informative analysis of major policy issues and pending legislation that accounts for the range of perspectives held by RSC Members and within the conservative community. Yesterday you received a Policy Brief on copyright law that was published without adequate review within the RSC and failed to meet that standard. Copyright reform would have far-reaching impacts, so it is incredibly important that it be approached with all facts and viewpoints in hand. As the RSC’s Executive Director, I apologize and take full responsibility for this oversight. Enjoy the rest of your weekend and a meaningful Thanksgiving holiday….

Paul S. Teller

Executive Director

U.S. House Republican Study Committee

Paul.Teller@mail.house.gov

http://republicanstudycommittee.com

The idea that this was published “without adequate review” is silly. Stuff doesn’t just randomly appear on the RSC website. Anything being posted there has gone through the same full review process. What happened, instead, was that the entertainment industry’s lobbyists went crazy, and some in the GOP folded.

November 16, 2012

The SOPA debate, one year later

Last October SOPA, the Stop Online Piracy Act, was introduced in the US House of Representatives. (A companion bill, PIPA, was in the Senate.) SOPA occasioned a lot of debate and ultimately led to some unusual activity, such as Wikipedia going dark for a day in protest. Most importantly, SOPA represented an unusual defeat of the legislative agenda of the entertainment industry.

While the battle over online piracy continues, SOPA led to an unusual alliance of stakeholders that proved formidable. Pam Samuelson of Berkeley has a nice short summary of the SOPA debate entitled Can Laws Stop Online Piracy? that just went up on SSRN here.

November 15, 2012

Is this copyright infringement?

The painting on the left is by a Chinese-born artist named Zheng Li. It’s called “Piano No. 9″. Li is not exactly an art-world fixture. For years, he lived in the U.S. and ran an art gallery in Roswell, GA. He has sold art to private individuals and corporations. But as far as we can tell, he hasn’t broken through to broader public notice.

The painting on the left is by a Chinese-born artist named Zheng Li. It’s called “Piano No. 9″. Li is not exactly an art-world fixture. For years, he lived in the U.S. and ran an art gallery in Roswell, GA. He has sold art to private individuals and corporations. But as far as we can tell, he hasn’t broken through to broader public notice.

That may change now. The painting on the right, titled “Piano Coloratura” and signed by someone named “P. Robert”, has been on sale in major outlets such as Kohl’s, J.C. Penney, and Z Gallerie. Li has sued all of these retailers, plus over 20 more who have sold “Piano Coloratura”, claiming that they are infringing his copyright in “Piano No. 9″.

Does Li have a case? Well, the paintings are certainly very similar, and that alone may get Li quite far with a jury. But if we look closer, it’s actually a really close case, and the correct outcome is difficult to call. Why?

Given how similar the paintings are it’s hard to believe that Li’s painting wasn’t copied. But if you break the paintings down, you’ll find that a lot of the copying at issue here isn’t actually illegal. For example, both paintings show a baby grand piano. But Li cannot own copyright in all pictures of baby grand pianos. And indeed, the baby grand in “Piano Coloratura” looks a bit different from Li’s piano. It’s shaped just a bit differently — and these small differences matter because all baby grand pianos look much alike, at least in their overall shape. Similarly, the “Piano Coloratura” piano is rendered at a similar angle to Li’s piano, but again, Li doesn’t have copyright in rendering pianos from the side. The pianos are also painted in a similar style using patches of bright color. But again, the execution of the style is not the same — the borders between colors are less distinct in Li’s painting — and, more broadly, copyright should not give any one artist ownership of a particular style of painting. Does impressionism belong to the first impressionist? Cubism to the first cubist? The same goes for colors. Copyright doesn’t allow anyone to own a color (trademark does, in a more limited sense that is not relevant here . . .).

So, is there a copyright claim? Yes. Li has a copyright claim in his original selection and arrangement of these otherwise uncopyrightable elements of subject matter, style, and color. In other words, Li has a copyright in the particular sum of the uncopyrightable parts.

The real question is how broad, or “thick”, a “selection and arrangement” copyright like this should be. Clearly, Li should have a copyright claim against anyone who reproduces his painting exactly — if the selection and arrangement copyright means anything, it must prohibit precise replication of Li’s painting, as would happen if someone simply pirated it and printed up a thousand copies. But how far should Li’s “selection and arrangement” copyright go in prohibiting mere “look-alike” paintings? That’s a very deep question, and one which is unsettled in the copyright law.

“Piano Coloratura” is not an exact copy. But it is pretty damn close. This is a borderline case. We’ll be watching.

November 12, 2012

Knockoff Science

Regular readers know that while we take a relaxed and even–at times–positive view toward copying in the copyright and patent contexts, there are lots of hard cases. Many of those revolve around trademark copying, where the need to balance the freedom to compete, comment and parody and so forth against the risk of consumer confusion makes for difficult line-drawing exercises.

Regular readers know that while we take a relaxed and even–at times–positive view toward copying in the copyright and patent contexts, there are lots of hard cases. Many of those revolve around trademark copying, where the need to balance the freedom to compete, comment and parody and so forth against the risk of consumer confusion makes for difficult line-drawing exercises.

Here is a good example: the CATO Institute, a libertarian think tank in DC that is often pretty smart and reasonable, seems to be either spoofing the government or deliberately trying to confuse the media (and others). Its recent report on climate change mimics the cover and layout of an official federal report, only of course it a product of a private organization with a specific view (one I tend to disagree with pretty strongly) on this particular issue. Judge for yourself from the covers above. For more see the story at Wonkette.

November 11, 2012

Apple and HTC call a truce in one battle in the smartphone war

News today that Apple and the major Taiwanese smartphone company HTC have reached a settlement in their long-running patent battle. Apple had won several important rounds, including a patent judgment in the U.S. International Trade Commission that enjoined HTC from importing into the U.S. several of its popular phones.

News today that Apple and the major Taiwanese smartphone company HTC have reached a settlement in their long-running patent battle. Apple had won several important rounds, including a patent judgment in the U.S. International Trade Commission that enjoined HTC from importing into the U.S. several of its popular phones.

Now HTC can get back to business. But notice that the terms of its licensing deal with Apple are secret. So watch closely. Will HTC re-emerge as a vigorous competitor in the smartphone market, as it was before the ITC ruling? Or has Apple succeeded in imposing on HTC such a significant “patent tax” that its competitive vigor will be reduced?

Time will tell.

November 10, 2012

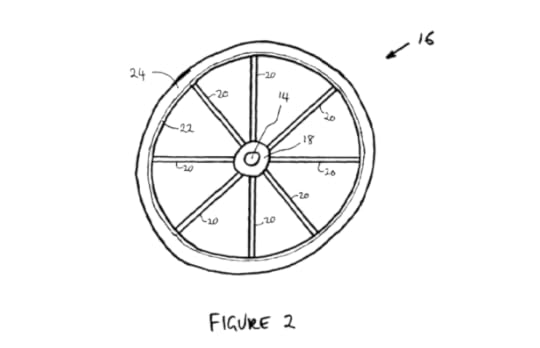

Don’t Copy That Wheel

From The Atlantic:

The Wheel

In 2001, Australian John Keogh patented a “circular transportation facilitation device” (PDF). Keogh, a freelance patent attorney, filed for and received his patent on the 5,000-year old contrivance in order to demonstrate flaws in Australia’s “innovation patent” system for fast-tracking legal protection of new ideas.