Christopher Sprigman's Blog, page 6

October 28, 2012

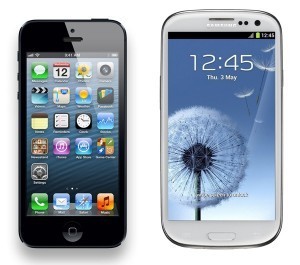

Everything’s A Rectangle

The NYTimes BITs blog has a post about the evolution (or maybe devolution) of design in smartphones and tablets. As they note, designs have increasingly converged on a key shape: the rectangle.

The NYTimes BITs blog has a post about the evolution (or maybe devolution) of design in smartphones and tablets. As they note, designs have increasingly converged on a key shape: the rectangle.

In the past, electronics makers could convince consumers that the design was different, because it actually was. The first iMac, for example, was a blue bubble. Then it looked like a desk lamp, and now it’s a rectangular sheet of glass with the electronics hidden behind it. The iPod designs changed, too, over time, before they became progressively smaller sheets of glass.

Certainly makers add features like better cameras or tweak the software — Siri and Passbook on the iPhone are examples of that for Apple — to persuade people to upgrade. But in the last few years, consumer electronics have started to share one characteristic, no matter who makes them: they’re all rectangles. Now, companies like Apple, Amazon, Microsoft and Google need to persuade consumers to buy new rectangles once a year.

This trend only reinforces the concerns we have with a firm locking up specific shapes via design patents. Now, one might quibble and say, copying is the reason there is so much sameness–it is all “me too” designs. But I think that is only part of the story. Slim rectangles have a major advantages, both for ease of carry and for use as a media consumption devices. As the Times story goes on to note, the rise of similar designs in TVs ultimately drove prices way down. That’s a nice feature too.

October 25, 2012

The Knockoff Economy on Hearsay Culture

And now Apple wins a round . . .

. . . this time in the United States International Trade Commission. An administrative law judge at the ITC has ruled that Samsung has infringed four Apple patents, including one of Apple’s “rectangle” iPhone design patents, and utility patents including pinch-to-zoom. The ruling, if upheld by the full ITC, could result in a ban on the importation into the U.S. of a number of Samsung’s products. We’ll see what happens next . . .

. . . this time in the United States International Trade Commission. An administrative law judge at the ITC has ruled that Samsung has infringed four Apple patents, including one of Apple’s “rectangle” iPhone design patents, and utility patents including pinch-to-zoom. The ruling, if upheld by the full ITC, could result in a ban on the importation into the U.S. of a number of Samsung’s products. We’ll see what happens next . . .

Apple loses a round in its patent war with Samsung

News that a Dutch court has ruled that Samsung has not infringed Apple’s patent on smartphone “pinch-to-zoom” — i.e., the function of zooming on a smartphone screen using a two-finger gesture. Apple’s billion-dollar patent victory in U.S. federal court in California is surely the big event thus far, but outside the U.S. Apple has been on a bit of a smartphone patent losing streak, with judgments coming down against it in courts in the U.K., Japan, Germany, and now the Netherlands. This is going to be a long war, but so far the result is unclear — both sides have won some important battles.

News that a Dutch court has ruled that Samsung has not infringed Apple’s patent on smartphone “pinch-to-zoom” — i.e., the function of zooming on a smartphone screen using a two-finger gesture. Apple’s billion-dollar patent victory in U.S. federal court in California is surely the big event thus far, but outside the U.S. Apple has been on a bit of a smartphone patent losing streak, with judgments coming down against it in courts in the U.K., Japan, Germany, and now the Netherlands. This is going to be a long war, but so far the result is unclear — both sides have won some important battles.

October 23, 2012

October 22, 2012

Starbarks

Copying trademarks is a different animal than copying copyrighted goods. But there are many interesting cases of trademark copying, and a surprising number of these involves dogs.

Famously (to IP lawyers) “Chewy Vuitton” dog chew toys were sued by Louis Vuitton, but prevailed because Chewy Vuitton toys were deemed a parody of a very famous mark that few, if any, customers would think was actually made by LV.

Recently, a similar dispute has unfolded over “Starbarks” dog care. Starbucks isn’t a fan and has threatened legal action. As the Chicago Sun-Times reports, the Starbarks team has suggested some fixes, but to no avail:

It’s true that the Starbarks Dog Daycare logo looks a lot like those green, black and white signs that beckon coffee drinkers into Starbucks.

But Starbarks clients seem to think it’s cute — not confusing. “Can Starbucks seriously be more petty?!” wrote one supporter in a typical comment on Starbarks’ Facebook page.

“I love the name. Everyone loves it. It’s clever,” McCarthy-Grzybek said. “It’s not like we sell coffee or anything they do.”

She added that she has offered to change the green in the logo to yellow and the stars to paws, but Starbucks wasn’t biting.

This case, like many others involving well-known marks, relies on the idea of trademark dilution. The underlying notion is that while no one will be fooled into thinking Starbucks is now in the dog care business, uses like Starbarks will ultimately erode the value of the Starbucks mark, either by blurring its meaning or tarnishing its reputation for quality. As our friend Rebecca Tushnet notes in the story, “Often this is not a battle that the small businesses can afford to fight in court. They can only fight in the court of public opinion.”

October 21, 2012

Copying in the Kitchen

The restaurant critic for the NY Times is one of the most powerful posts in the food world. This week the current critic, Pete Wells, wrote a very interesting post on his “Diner’s Journal” about copying among chefs. Years ago Wells wrote a great story for Food & Wine magazine called “The New Era of the Recipe Burglar,” so this is nothing new for him.

The restaurant critic for the NY Times is one of the most powerful posts in the food world. This week the current critic, Pete Wells, wrote a very interesting post on his “Diner’s Journal” about copying among chefs. Years ago Wells wrote a great story for Food & Wine magazine called “The New Era of the Recipe Burglar,” so this is nothing new for him.

Here’s what he had to say this time:

Not long after I wrote about Katy Peetz’s watermelon radish dessert at Blanca, a blogger pointed out on Twitter that it looked “awfully similar” to a dessert served last year at Dirt Candy, Amanda Cohen’s vegetable restaurant in the East Village.

Ms. Peetz made watermelon radish gelato in September, while Ms. Cohen had a watermelon radish sherbet on the menu from July to December of last year. Radish ice cream isn’t exactly as common as chocolate chip. On the other hand, it is possible to imagine that two chefs, both fond of vegetables and both regular visitors to the twilight zone between sweet and savory, arrived at the idea independently.

* * *

Certain words make journalists and their editors jumpy. Words like first, last and greasiest. All it takes is one reader pointing out something that was earlier, or later, or greasier, and you’re publishing a correction.

One word that makes me jumpy these days is “original.” I have seen a number of dishes that struck me as brand-new, never-before-seen innovations, only to find out later that they bore a striking resemblance to another chef’s work. I agree with Ms. Cohen that this kind of thing happens all the time, and that it’s generally healthy and good for creativity.

October 19, 2012

Samsung FTW

The Apple vs Samsung courtroom smackdown is a global affair, and judgments have, shall we say, varied based on where a particular suit is heard. Yesterday, the UK jumped in with another ruling, this time in Samsung’s favor. From the BBC:

Apple loses UK tablet design appeal versus Samsung

A UK judge had said he thought few people would confuse the Galaxy Tab computers with Apple’s iPad

Apple has lost its appeal against a UK ruling that Samsung had not infringed its design rights.

A judge at the High Court in London had originally ruled in July that the look of Samsung’s Galaxy Tab computers was not too similar to designs registered in connection with the iPad.

He said at the time that Samsung’s devices were not as “cool” because they lacked Apple’s “extreme simplicity”.

Apple still needs to run ads saying Samsung had not infringed its rights.

The US firm had previously been ordered to place a notice to that effect – with a link to the original judgement – on its website and place other adverts in the Daily Mail, Financial Times, T3 Magazine and other publications to “correct the damaging impression” that Samsung was a copycat.

The appeal judges decided not to overturn the decision on the basis that a related Apple design-rights battle in the German courts risked causing confusion in consumers’ minds.

“The acknowledgment must come from the horse’s mouth,” they said. “Nothing short of that will be sure to do the job completely.”

However, they added that the move need not “clutter” Apple’s homepage as it would only have to add a link entitled “Samsung/Apple judgement” for a one-month period.

A spokeswoman for Samsung said it welcomed the latest ruling.

“We continue to believe that Apple was not the first to design a tablet with a rectangular shape and rounded corners and that the origins of Apple’s registered design features can be found in numerous examples of prior art.

“Should Apple continue to make excessive legal claims in other countries based on such generic designs, innovation in the industry could be harmed and consumer choice unduly limited.”

Apple declined to comment. It can still appeal to the UK Supreme Court, otherwise the ruling applies across the European Union.

October 18, 2012

The power of performance and brands

Our latest post at The Volokh Conspiracy is about the power of performance and brands to spark innovation. Here’s a taste:

Our latest post at The Volokh Conspiracy is about the power of performance and brands to spark innovation. Here’s a taste:

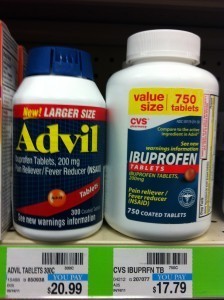

“The power of brands is very apparent in any big drugstore. Walk into a CVS, and you can buy, for $20.99, 300 tablets of Advil brand ibuprofen. That is just under $0.70 per tablet. The CVS private label ibuprofen—which contains exactly the same dosage of the same medicine—costs $17.79 for 750 tablets, or about $0.24 per tablet. The Advil brand ibuprofen, in other words, is almost three times as expensive as the CVS ibuprofen, despite the fact that they are functionally indistinguishable.

As this shows, brands have a strong power over price. And as a result, they wield an unexpected ability to spur innovation. The story of ibuprofen can help explain this relationship. Ibuprofen was invented in the early 1960s by the UK firm Boots, which runs a large chain of drugstores. First patented in 1961, it was introduced in the United States as a prescription drug in 1974. In 1984, the FDA approved ibuprofen for over-the-counter (OTC) sale. That same year, Pfizer reached a license agreement with Boots and introduced OTC ibuprofen under the brand name “Advil.” Boots’s US patent expired in 1986, and soon after other brands of ibuprofen entered the market.

So in all, Pfizer’s Advil brand of ibuprofen had less than two years of market exclusivity in the United States. After those two years, many competitors jumped in. And yet today, almost 25 years after the expiration of the ibuprofen patent, Advil still owns 51% of the market. That’s more than twice the combined share of all generic ibuprofen products, despite the fact that Advil is functionally equivalent to its rivals and quite a bit more expensive.

Why are consumers willing to pay so much for certain brands? There is surprisingly little consensus among researchers about this. Part of the brand premium is surely based on perceived quality differences, and some studies suggest that beliefs about quality may account for perhaps 20% of the difference. But this rationale makes less sense in the case of a basic pain reliever like ibuprofen, where the FDA certifies that the generic drug is as safe and effective as the branded pill. The brand itself seems to have some effect on the willingness of consumers to pay more.

What’s the upshot? Brands can keep prices high and give firms large and resilient market shares. That brands can have such huge effects explains why companies spend so much money promoting them and designing nifty names and symbols. This much is well known. But the power of brands also has important implications for innovation. If an innovator can link her innovation to a successful brand, she can maintain pricing power even after her innovation is copied. This is the key takeaway of the ibuprofen story. The patent on Advil gave only two years of monopoly control. Yet decades later, Advil still dominates the market for ibuprofen. This suggests that whatever the period of exclusivity, if the brand is sufficiently well-established the innovator can continue to profit—substantially—even after the entry of copies, and even if the copies are quite literally identical products. The brand, in effect, can substitute for the protection against copies offered by patent or copyright.

This is a big topic, and exactly how brands do this is poorly understood. Which means we should try to understand it better. Brands serve as handy identifiers that help consumers more efficiently select the product they want when they’re out shopping. But brands also appear to have an important and unappreciated role in sparking innovation.”