Sarah McCarry's Blog, page 9

October 25, 2013

A Conversation With Imogen Binnie

Imogen Binnie's debut novel, Nevada, is a smart, poignant, funny story about a young lady who is very good at getting herself into trouble and not quite so good at getting herself out of it. I loved the hell out of it when I stumbled across it earlier this year. Imogen Binnie--who is herself, unsurprisingly, very smart and funny--was nice enough to answer a few questions about the book, writing groundbreaking fiction, and whether or not there's hope for fuckups.

So it is a really common thing for female fiction writers to be asked if their work is autobiographical, as I am sure you've noticed, and I would imagine this gets even more complicated when you've written a book like Nevada. How do you feel about the autobiography question? Are you sick of it? Do you think it can be productive?

I'm actually not that sick of the autobiography question! I think it's definitely a complicated one, though. Like, the kind of books about trans people that have tended to be published--especially about trans women--have tended to be memoir. And I think the dynamic at play is that trans memoir is supposed to explain The Trans Experience for cis people: "this is what it's like." But what it often does is to frame the assumed cis people audience as "us" and the trans person explaining transsexuality as "them" in a way that maintains the cultural othering of trans people; so while trans memoir is intended to make trans people understandable to cis people, it doesn't really make us... equal? Or something? I dunno like I only ever felt like Jennifer Finney Boylan's writing was relevant to my life before I transitioned.

And so one of the questions I was trying to answer with Nevada was, what would a story about trans women that was intended for an audience of trans women--what would that look like? It wouldn't just be like, "this is what it's like to transition." There would have to be some kind of, like, plot? Which I'll admit, right, I wasn't reading Robert McKee and putting together a five-act plot arc with a denouement while I was writing Nevada; I was trying to do something a little more blunt and mean with the plot. Which hasn't worked for everyone who's read it!

As an aside, I just read a collection of Joanna Russ's essays about women's writing and science fiction and all the things Joanna Russ writes about and she has an essay called "What Can A Heroine Do" where she writes about the question of whether the western patriarchal plot can actually serve a female character in the same way that it does a male character. She turns it over in a few other essays, too, but what she concludes is that the three-act sort of classic narrative arc doesn't, actually, work for telling women's stories. I wish I could remember the specifics better but the end of the story is that she talks about sort of elliptical plots which don't resolve in an Ending as a possibility in women's writing and I was like, whoa, I think that is a thing I sensed without putting into words and did in Nevada?

Or else I heard Joanna Russ's ideas, internalized them and then forgot I'd heard them.

Alternately I was just trying to be Kathy Acker.

Whichever is the case, part of the project for the next novel I'm writing (codename: "Keep The Piss Christ In Piss Christmas") is to write a normal goddam plot. I *am* reading Robert McKee this time.

Anyway, to get back to your question, the thing that *is* frustrating for me is when people assume that I called Nevada a novel but actually it's just memoir or slightly fictionalized memoir. I grew up reading Stephen King and I always assume the parts of Stephen King characters that are dudes who listen to classic rock and like to talk in folksy aphorisms are more or less fictionalized memoir, but the parts about monsters and stuff are not. Nevada's like that; I've worked in bookstores and eaten bagels. Sure! And I've been a hopeless and depressed barely-post-teenager in a relationship that didn't have a future. But... never in Nevada? Y'know. The stuff I wrote about in my novel was not entirely removed from my life. But neither was the shit Hemingway wrote about removed entirely from his life, either. So I am like Ernest Hemingway in that way.

Maria is very good at theorizing her experience but not so great at actually making Healthy Choices In Her Life, and a lot of that is specific to her being a working-class queer punk trans woman in a world that is not a particularly hospitable or welcoming place for any one of those things, let alone all of them--but I also feel like that more general experience of being able to articulate and theorize why exactly you're fucking up even as you're continuing to fuck up is a really, really relatable one. For me, anyway. That's not a question, I always do this when I interview people. But I guess I'm interested in that process of learning to love yourself, and take better care of yourself, as an act of survival and of resistance--do you think Maria will get there? (Will any of us? SAY YES)

Yes! I would love to see Maria learn from it and figure out that, like, she wasn't able to help this kid. Being a mentor didn't solve her problems, right? So what will? She's looking for an answer and while she's not great at it, she sure hasn't given up. So she'll try something else, and try something else, and then try something else, and then eventually if she gets old she'll look back and realized that she learned some stuff from every thing she tried and has actually grown a lot, just not in the sort of fireball explosion of solutions that all of us wish we could stumble into. If that makes sense?

So I guess in other words yeah she'll get there, as much as any of us get there. And I think a lot of us get there.

And to respond to another thing in your question (which *was* a question!), I don't think Maria's problem is only that she lives in a world that's not hospitable or welcoming. I think a big part of her problem is that she's got the theory but she doesn't have the practice? James and Maria both talk about being really involved in the internet without being involved with other people that much. Maria even talks about not liking other trans women. But how fucking good would it be for Maria and Piranha to start... I don't know, an angry punk trans women-only foosball league or something? An important thing she's gonna need to learn if she's gonna Get There is to exist in the real world. How do we learn that? I mean... I don't know how to learn that, exactly, but busting through her apprehension and approaching a kid in a Wal-Mart who she thinks might be trans, that is a serious and legitimate step toward existing in the word. Which I think is a good reason for Nevada to be a story about this specific period of her life.

Nevada is a groundbreaking book--in addition to its being an awesome, fantastic novel, there is not exactly a broad canon of punk trans lady literature. Did you feel that pressure while you were working on it? Or was it freeing?

Y'know... sure. Yes. It wasn't that strong but sometimes I'd get stressed about it. But the thing about writing a first novel is that who even knows if it'll get published? I did set out with the explicit project of writing a novel that was true to the experience of a certain demographic of trans women, and I did set out with the project of getting it published somehow. But I mean. I dunno. I've got all the same conflicting punk rock ethics that Maria does, so it felt important to tell the truth about this stuff in the best way that I could. Not in a "this is gonna change the world" way necessarily, but at the very least in a "this might help" way. And I couldn't imagine another "this is what it's like to start hormones, this is what it's like to come out at work" story really helping. So it was freeing and there was some pressure.

I guess also there was a component of feeling so frustrated and jaded and sick of reading trans stuff--even when I started writing Nevada, in 2008--that just didn't feel like it was for me. Right? Having a specific audience in mind--trans women--was probably the main thing that kept me on track with this stuff. And I feel really lucky that it resonated so much with people who aren't trans women too; I mean, I think everybody who blurbed it is either a cis woman or a female-assigned genderqueer person. (I'm not certain about everybody's identities!) So... I dunno. One piece of wisdom that I guess I know is that if you try to make a thing for everyone you're gonna make a thing nobody's gonna like (unless the groaning, planet-destroying machinery of capitalism coerces them into it, but I don't have the keys to those machines) so I at least had a lot of faith that I could do a good job making a thing for trans women.

Maria's story is in part a hilarious subversion of the Great Dude Road Novel--are there any classic road novels you particularly love, or loathe, or were thinking about when you were writing?

Haha, no actually. I didn't conceive of it as a road novel at all! I mean, in retrospect, that is a trope that seems to have been subverted, but I don't think I've ever even paid attention to that genre enough to be able to play with it. I'm like... I think I read On The Road in high school? And one time I got this book Chick Flick Road Kill that looked pretty good, but I haven't read it yet.

But structurally, I was like, this is a novel about trans women where the transition happens off stage. It's a novel with a sock full of drugs at the center of it, which--spoiler, seriously, spoiler--nobody actually takes, at least not on stage. And it's a novel about a road trip where all the traveling takes place offstage? The idea that it was a novel about trans women where nobody transitions over the course of it was, like, where I started with it. Then I was like, okay, so I'll have someone who hasn't transitioned yet, and somebody who transitioned a while ago. And then from there that theme just sort of stuck around and popped up in other ways too. So... Uh, I don't know anything about road novels. Haha.

What are you working on next?

The elevator pitch is that it's a novel about ghosts, the apocalypse and tumblr! More trans women. I don't want to say too much, because who knows what'll happen over the course of writing and editing. But those things will probably be in it.

What are some great books you've read lately?

NOS4A2 by Joe Hill was SUCH a good horror novel! And there was only, like, one sentence that I was like "aw c'mon dude really you just HAD to put that in there?" I love horror stuff but I feel like I can never recommend it because so often it's got so much misogyny or straight white cis dude bullshit or whatever. Cross out that one sentence though--you'll know it when you get to it--and NOS4A2 was maybe the best book I've read this year. I've also been reading Gillian Flynn, who writes these brutal novels about women and violence and memory and stuff. There might be too much triggery stuff for me to be like "I recommend this," but she definitely knows how to get a story off the ground. What are some great books YOU have read lately? [THE GOLDFINCH, also The Bridge of Beyond, also actually I am working on a post about this, so more at length shortly. --ed]

October 15, 2013

goodbye to none of that

Everybody keeps writing essays about the pleasure and pain of leaving New York and I mean, I get it, but I'm not going anywhere.

I moved the drafting table in my apartment over by the window and that's where I've been working; my apartment is tiny but its windows are big and when I write back cover copy for criminology textbooks I like to look out at the trees across the street. "You must make a pretty good living now, writing books," an acquaintance said to me, and I didn't want to be rude or depressing so I just laughed.

If I do go it'll be back to the peninsula, and alone: I have vague and hazy dreams about a little house on a lot of land, holed up with my books and guns and pitbulls, running solo marathons on the weekends and fasting in the mountains. In this fantasy I have acquired a prodigious set of backcountry, off-grid survival skills: installing solar panels, growing my own food, butchering cattle. This is, admittedly, unlikely. But just think--perhaps some romantic, ambitious project, in the quiet, lonely nights--reading all of Proust (in the original French, of course) while I wait, patient and certain, for the apocalypse to come.

I'm as guilty as anyone of waxing rhapsodic and unnecessary about this city, but what began as a desperate survival strategy (OF COURSE it's grand here OF COURSE it's grand here OF COURSE it's grand here, oh god, oh god) has turned into something less epic, less frantic, and more true. New York will never be home for me, not in the way the still green places of the peninsula are home, grey water against grey sky, gulls wheeling on the salt breeze; but home will never be large enough to hold me, and New York is the only place I have yet lived that is. Its brassy and ostentatious magic, its excess and its harshness, its filth and its glory, the hard and brutal labor of making a living, making a life here--a lot harder if you are poor, yes, but there are more than a few quite poor and somewhat poor and almost poor people here, calmly getting by and being happy sometimes, which nearly every exegesis I've read on one white person's final, mournful exodus has managed to overlook--are not for everyone, and if you do not find some love in living here there is not much reason to stay. But I would be sorry, right now, to go anywhere else.

The first few years I lived here were the hardest of my life and since then I have been very lucky. It's a luck, I am well aware, that could run out at any moment, and if it does there are not a whole lot of doors that remain open to me. I keep my fingers crossed and don't ask too many questions, work hard to not think about that sea of terror named the future. When I was really broke I would wake up crying every morning at four a.m., regular as a metronome, but I am not so broke now and more likely to sleep through the night, and decent dreams make for better days.

What I meant to get to was that there are a lot of us here, not rich, artists, making it work, because to us it is still worth it for as many reasons as there are people living here, a different reason for every person, a different ambition, a different joy. It is hard in New York but if you are poor or queer or trans or brown or female, weird, messy, cuss too much, too likely to get too drunk, crazy, causes trouble, strange clothes, way too big a cunt to be well-loved in Portland, it is fucking hard for you everywhere. All kinds of people make lives here and everywhere else, make art here, fall in love, have kids, build communities. Get in fights and work and write about themselves on the internet, forever, and then get sick of themselves talking about themselves, and then keep doing it, not that I have any experience with this personally. The shit you do when you are human. Living in New York is like living in a constant allegory for the terminal stages of capitalism but that doesn't make me love it any less. "At least it's honest here," I say to the cat, drinking a beer at my desk and looking out at the lowering dark. And then I go see my friends.

September 28, 2013

chloe does the tables

I come back to the peninsula over and over again. A toddler worrying at a loose tooth: no wiser than that, no older in my heart. Now I am leaving and I keep writing things about it and then deleting them because I am bored of myself talking about it and I always have more to say about it and then I am bored of myself in the middle of saying the same thing again and I go sit on the beach and look at the water and think what is the lesson I am supposed to be learning, and then usually I cry. Rinse, repeat. Circling something, over and over. The nature of the circle is that it has no beginning, no end, no resolution.

On this trip I got a massage from a woman named Savinka who told me I clench my jaw because I am keeping too many secrets and I pull my shoulders in too far because I am holding something I do not know how to release. "You cannot waste all this time being angry," she said, "because your health is more important," and I thought anger has kept me alive, but I don't know if that is true anymore or if it is a story I tell myself to justify how angry I am. How do we live with what we are? with what has been done to us? with what happens now, yesterday, tomorrow, to the people we love and the people we do not know? How is anyone not angry? I think people who are not angry are my enemies but maybe I am someone who looks too much for fights to pick.

Then again, I am still alive. And it's by counting scars that I find the people I love best.

A guy found me in the bar downtown and told me the story of his life, the way they do. I didn't tell him any stories of my own. I wouldn't have even if he'd bothered to ask. "But in the end, it's best to be honest about what you are," he said, reflecting on the foibles he'd outlined for me. "We're all polished turds." "Speak for yourself," I said, and he looked startled to realize I had a voice. "I'm diamond all the way through."

I wrote about Medea and I am writing about Medea and I am still thinking about Medea, the monster, the girl, and how the body of monster is the only body that feels large enough to hold the girl that I am and have been. Reign in blood. Out west I feel mean and tired and homesick and out east I feel fragile and tired and homesick but it's almost winter, and that's my season. And out here I look and remember there are stars, uncountable, and the tide goes in and out, and the gulls wheel around in the sky and holler at you, and the deer gaze at you with big dopey eyes before they go back to eating people's gardens.

This place we used to go to for years and years, this cliff overlooking the beach called the End of the World, fell into the sea last week. It sounds like a metaphor but it's actually just the truth. It's the end of the world as we knew it and I feel fine. I'm hanging in there and I hope you are too. xo.

August 27, 2013

A Conversation with Lisa Brackmann

Lisa Brackmann is the author of the novels Rock Paper Tiger, Getaway, and, most recently, Hour of the Rat, a sequel to Rock Paper Tiger. She writes great, funny, sharp books about complicated lady characters thwarting dastardly plots, eluding nefarious villains, and generally getting themselves into--and out of--trouble. I've been a huge fan of her writing since I first read Rock Paper Tiger and fell in love with its glorious mess of a heroine, Iraq vet Ellie McEnroe. Lisa took some time to chat with me about publishing, politics, and writing characters who take you places you don't always want to go.

You've said that it can be extremely difficult for you to "channel" Ellie--she's a character who often goes to difficult and dark places, both literally and emotionally. Can you talk a little bit about what it's like to spend so much time with such a complex and sometimes hard-to-write character?

Mostly it’s fun. Ellie’s observations often have an edge of humor, and it’s fun capturing her voice—I always have to think about how Ellie would say things, because she’s not going to use a lot of fancy language to describe something, but her observations are still sharp and on target. I really enjoy depicting China through her eyes. But Ellie is a younger person than I am, and the intensity of her feelings is higher, and trying to put myself in that mindset all the time can be draining.

Hour of the Rat was pretty much just a lot of fun to write, coming as it did a couple of years after Rock Paper Tiger. I’d had some time to think about Ellie and where she was at the end of that book and how her experiences might have changed her and where she should go next.

Jumping right back into her head for the book I’m working on now was more of a struggle. I was going through a lot of my own transitions and I wanted to feel positive and in control, and instead I’m channeling the 27-year old who has some PTSD and a Percocet problem. It’s been especially challenging because I need to wrap up (at least provisionally) some of the threads that have run through the first two books, and I really wrestled with a lot of those decisions. At times it’s felt like I had to be in a negative place myself to know where I needed to go for the book. I don’t necessarily recommend this kind of Method plotting.

With each of your books, you pull off the near-impossible feat of working politics seamlessly into smart and well-plotted thrillers. Why do you think it's important to deal with larger social issues in your fiction? What role--if any--do you think fiction can play in pushing for social change?

I think it’s important for a number of reasons. On a personal level, I have always wanted to understand how things work, how the world is run, so writing books that deal with political issues is a way for me to process these problems and situations and make some sense of them for myself.

When you study and think about these kinds of issues a lot, there’s a point you come to when the understanding can lead to thinking about better ways of doing things, and then, action. But you have to understand the issue first.

That’s where I think fiction can be important. If you embed political issues deeply enough into the narrative so you’re not doing a didactic info-dump, then your characters and story have to carry those ideas. And that can be a way of communicating ideas that isn’t as heavy-handed or maybe off-putting to some readers, because you’re asking them to relate to characters and story more than hot button topics that might have a lot of ideological baggage.

I guess I actually do believe in memes, not just in the Grouchy Cat sense, but as units of ideas and symbols that spread from person to person and through cultures and that eventually transform them. So how are memes transmitted? And you have to conclude that the arts are some of the most effective transmitters we have.

You travel regularly in China--did you always know you'd set a book there? How have your experiences traveling informed your work?

The first time I went to China was in 1979. I was young, and not all that many Americans had been to China in my lifetime. I was there for six months, and sometimes I think of it in dog years, because the experience had an outsized impact on my life. When I came back to the U.S. everybody said I should write about it because at the time a young American who’d lived in China was pretty unusual.

But I really couldn’t. I was too young and too green a writer. I just wasn’t able to digest it all enough to make the kind of sense that I could write about.

When I started going back to China regularly a couple decades later I thought it was to work on speaking Mandarin, which I’d just started studying again. What I realized I was really doing was excavating my own past. It was an answer to the David Byrne lyric in “Once In A Lifetime”—“And you may ask yourself, well, how did I get here?” And when I went back to China, I thought, “Oh. This explains a lot.”

It wasn’t until about 2006 or 2007 that it occurred to me I could write fiction set in contemporary China, and that this might interest people.

I’d say that my experiences traveling in China permeate the work—the Ellie books are so much about setting and very specific details of places.

One of my motivations for writing the books is that I want to write about China in a way that helps people visualize it and understand that China is a place like any other place. Yeah, it’s interesting, yeah, it’s weird and surreal at times, but honestly, you can say that about all kinds of places. I mean, I’m a native Californian. I was really surprised when I left the state and found that even a lot of my fellow Americans thought California was really exotic. And, okay, California is objectively pretty damned interesting, but for me it’s where I was born and where I grew up and it’s what seemed normal to me. So I try to approach depicting my settings the same way: Oh yeah, really interesting. Oh yeah, really normal.

We have talked a lot about the joys and perils of making a living as a full time freelancer/writer. What are your favorite parts of being a career writer? What do you find most challenging?

As a writer, I consider that my job is to learn stuff, think about things and write about it all. It’s telling a story in an interesting and human way. It’s playing with language to get the effects that you want. All of this is exercise for nearly every part of your brain, and anything that’s so challenging is also really engaging. And finishing a book, it feels like a real and substantial accomplishment. You don’t get that level of challenge and engagement and satisfaction with most things you do in this world, at least, I don’t. So that’s definitely one of the best parts.

Another is meeting other writers, and publishing professionals, and book store owners and librarians, and of course, readers. When I was first published and started having these kinds of interactions, it felt like I’d finally found my tribe.

Going to China as a legitimate tax write-off, hard to beat!

Most challenging?

Money. Most of the downsides are around money.

There are very few novelists these days who make a living from their books. You’re either working other jobs or you have a supportive mate or an independent income. Yet you’re working very hard at a profession that requires a lot of skill and commitment and time.

Publishing has undergone all kinds of seismic shifts, as has the economy in general, and advances not only haven’t kept up with the cost of living, we’re seeing the same kind of disparity that you see in society at large, where there’s a very few authors making very big advances--and getting the big marketing and promotion budgets behind their books—with the great majority on the other end earning zero to small advances. You see the shrinking midlist and even some people who got the big advances who don’t get the marketing because the house has moved on to other priorities. Authors are responsible for more and more of their own promotion and are expected to do a lot of work that didn’t used to be part of the job description. I think most of us accept that this is the modern market and are willing to pull our weight. But these are things that take time and for which we are in general not directly compensated. If you’re working other jobs or if you have family responsibilities, the question becomes when, exactly, are you supposed to do all these things and still be writing books?

And sleep. I’m really fond of sleeping.

I’m very fortunate in that my publisher and my agency are extremely responsible partners when it comes to me getting paid (and promptly!), but I hear plenty of stories, and it amazes me how long it can take with some companies for contracts to be negotiated and checks to be cut. And there are structural issues in the industry that work against authors and for which I don’t think there’s much justification. Why are royalties only paid twice a year? Surely we could switch to quarterly at least. And the consensus is that authors are greatly undercompensated when it comes to e-book royalties. These aren’t global issues where there’s still a lot of flux and uncertainty; these are concrete, fixable problems.

I know we’re supposed to be writing books because we love to write or we have to write and to some extent this is true, but I feel like the demands on writers and other creative professionals can be pretty heavy. Trying to figure out how to do good work, to do the other stuff that comes with being a published author (the business and promotion and appearances), publish regularly and support myself has been a challenge. And in our society, there’s this attitude of, “You’re lucky to be published,” which I know is true, and “I want to read your book but I don’t want to pay much if anything for it,” and along with that, a sort of notion that maybe writers don’t deserve to be paid all that much.

And I get that a lot of people are struggling--it’s one of the reasons I am so happy that my books are in libraries, because I want people to be able to read them, and books, especially hardbacks, are simply out of a lot of folks’ budgets.

But there comes a point, namely, “I’m exhausted and stressed out all the time, and I think I’m getting too old for this,” where it’s hard to do good work. Because for all that I’ve tried to treat writing books like I’d treat any other job, it’s still a creative process, and sometimes you can’t just be creative on demand. In the rush for authors to act more like businesspeople and manage their careers and promote their work, I feel like we’ve almost lost sight of that.

What's next for Ellie? And Getaway's Michelle?

As mentioned, there are some unresolved issues that Ellie has to deal with. I don’t want to reveal too much, because if you haven’t read the books, I don’t want to post spoilers. For those who have read the books, I promise that some of your longer-running questions will be answered!

In the new book (I’m calling it “Dragon Day” for now), Ellie finds herself as usual in a situation that’s way above her pay grade. This time she’s reluctantly sucked into the orbits of some very rich and very powerful people, the Fu Er Dai and the Hong Er Dai in China, meaning “Second Generation Rich” and “Second Generation Red,” and some of these folks are extremely corrupt and not terribly nice. Ellie has to decide how many compromises she’s willing to make to protect her position in China, but in a lot of ways, she’s in another “damned if you do,” and “damned if you don’t” situation. There are a couple of murders that Ellie has to solve, so it’s a more classic crime novel in that sense, but a crime novel with Chinese characteristics, as it were.

As for Michelle, when we meet her again, she’s a very different person than the woman who drank all those margaritas on a Puerto Vallarta beach. She’s managed to build a new life for herself when an old nemesis re-enters the picture and threatens everything she cares about, and once again she finds herself playing a role in a very dangerous game. The difference is that this time, she knows what she’s getting into, and she’s a lot better prepared to do what she needs to do to survive. As in Getaway, the drug trade is involved, but also the prison-industrial complex and the relationship between the two. You know, the United States incarcerates a greater percentage of its population than any other country in the world, and the reasons for this are both complicated and appalling. So I’m really excited to be digging into these issues and serving them up with a lot of danger, a few chase scenes and a good dose of mayhem.

August 19, 2013

A Conversation with Ibi Zoboi

Ibi Zoboi has published short stories, essays, articles, and one picture book. She's received grants from the Brooklyn Arts Council and she works as a Writer-in-Residence in New York City public schools. Ibi is finishing up her MFA in Writing for Children & Young Adults at Vermont College of Fine Arts and is working on two YA novels, a middle grade, and a non-fiction picture book. She was nice enough to answer some questions about her new project, the Brooklyn Blossoms Book Club. The Blossoms' inaugural event will be a reading and signing with Rita Williams-Garcia on August 31.

Tell me about Brooklyn Blossoms Book Club! What's your ultimate plan for the book club? Who will be a part of it?

Well, the cutesy little name was my daughters' idea. They're ten and eight and they read lots, of course. I'm in the Writing for Children & Young Adults program at VCFA so my bookshelf is full of picture books, middle grade, and YA titles. My daughters are lucky to own nearly every single book featuring a black girl as its main character. I'm in a position to know what those titles are. Most folks are not. My daughters' friends' parents are not aware of what's out there for their daughters. When I read a good book that I know will empower a girl in some way, I want to hand out free copies at a schoolyard or something. That's how I felt about Rita Williams-Garcia's One Crazy Summer and P.S. Be Eleven. I just happen to have daughters who fit the age range for those books, and they have friends. So the Brooklyn Blossoms Book Club was inevitable.

But it's more than just a book club, of course. It's more of literacy initiative aimed at underserved girls in Brooklyn. By underserved, I mean the girls from neighborhoods with poorly funded libraries and no independent bookstore in sight. I want to hold book events in community centers or playgrounds and make certain books accessible to those who need them the most. I want our local libraries to be safe spaces for girls. Some libraries in Brooklyn are so underutilized. There are more young people waiting in line to use computers than there are sitting at tables reading books. It's not uncommon to see a girl making out in the corner of the library. I once a stopped a fight that was about to happen right on the steps of my local branch. I think the library staff spends more time babysitting than actually being librarians.

I want these girls to develop critical thinking and writing skills from book discussions. I want them to create skits from these books, make themed art projects, write book reviews, and interview authors on camera. I want literacy to be a multidisciplinary, engaging, and fun experience. I need these girls to begin to examine how they are portrayed and perceived in stories, and in the media in general, through the lens of picture books, middle grade, and YA titles. Ultimately, I want these girls to let the world know that they're brilliant, they have their own opinions, and they have the final say on what images and ideas they want to claim for themselves.

What drew you to organizing a project like this? What do you think storytelling can offer kids, especially kids who aren't used to seeing their own stories reflected in the media around them?

The one thing that we have all inherited as children is stories. Everything around us is the product of somebody's story, narrative, and mythology. For my grad thesis, I'm writing about girls of color in speculative fiction (sci-fi and fantasy) middle grade and young adult novels. Yes, I can count all such titles on both hands and maybe one foot. Both realistic and fantastic stories that feature girls of color can have a tremendous affect on how they see themselves within the larger narrative where nerdy white boys or even white girls with long flowing hair and princess dresses save the day. Even if we have more stories like this, those books have to get into the hands of girls whose English teachers don't have a clue, or whose libraries are not safe spaces, or the closest bookstore is a bus ride and several subway stops away.

You're a writer and a mom, and you've done a lot of community work with kids and young adults both in New York and in Haiti--how do all those different pieces of your life fit together?

Because I'm a writer and a mom, they all fit seamlessly together. I've invested a lot of time and money (read: MFA) into my writing. I'm writing about black girls, Haitian girls, immigrant girls. I don't really want to teach college or sit in an Ivory Tower discussing diversity in children's literature. I like grassroots organizing. That's where seeds can be planted.

How can we support Brooklyn Blossoms?

By support, do you mean money? Yes, money, please. Thank you. There are certain books that I think every African American, Latina, or immigrant girl should own. Chances are, buying books and building a home library is not a priority for many families. I'm thinking, you know how those charities have you sponsor a cow for a child in some village in a third world country? A book collection can be like a cow, yes? I'm in the process of setting that up. I'm in the baby stages where I have to see what the response is and how many participants I get.

What books did you read when you were a kid? And what are some books you've read and loved lately?

I didn't read a lot as a kid. I watched Norman Lear sitcoms instead. My mother was an immigrant and a single mother. I spent the early part of childhood in a neighborhood with no bookstore and it wasn't safe for little girls to go skipping to the library on their own. When I was about ten, my mother had brought home a pile of those Little Golden Books and shelved them right above the Encyclopedia Britannicas. She'd make me turn off the TV and tell me to read a book. Those two collections were my only options. I remember Judy Blume's books and the Chronicles of Narnia from my Catholic school's library. I didn't care for those. I wanted a book to tell me how to outwit my schoolyard tormentors. Not like those girls in Blume's Blubber, but books with real black girl, neck-rolling, finger-snapping sass.

I just love Virginia Hamilton's whole body of work, starting with Zeely. I recently read Nancy Farmer's A Girl Named Disaster and wish I'd read it much sooner. Rita Williams-Garcia's Jumped, One Crazy Summer, and P.S. Be Eleven. Nnedi Okorafor presents such rich, authentic, and complex futuristic African settings in Zahrah the Windseeker and Akata Witch. Coe Booth's Kendra, Meg Medina's Yaqui Delgado Wants to Kick Your Ass, Guadalupe Garcia McCall's Summer of the Mariposas, and Alaya Dawn Johnson's The Summer Prince are my recent faves.

August 5, 2013

A Conversation with Hilary T. Smith

Caption

Hilary T. Smith, formerly known as INTERN, is the author of Wild Awake, a lovely and funny and heartbreaking and huge-hearted novel about growing up and figuring out who you are. She was also one of my very first friends on the internet, but that doesn't make me biased, promise. It's a really, really great book.

One of the things I loved about Wild Awake is its refusal of a redemptive narrative arc--at the end of the book, there's no tidy solution for Kiri, though she does get some closure. Both Kiri and Skunk deal with their mental health in ways don't follow traditional narratives about "illness" and "treatment"--can you talk about why you made that choice as a writer?

If Kiri and Skunk don’t follow traditional narratives of illness and treatment, it’s because I’ve become less and less comfortable with those narratives over the years. Metaphors and similes have tremendous power, and some of the most popular ones in mental health discourse right now are sort of insidious, if well-intended.

For example, “Mental illness is just like diabetes or [insert disease here].” On one hand, this is intended to destigmatize mental illness; on the other hand, it glosses over the incredibly complex factors that go into making and keeping a person “mentally ill” (not just biological, but social, cultural, political…) while holding up lifelong medication as the sole and uncontestable solution (“you would take your diabetes medicine, wouldn’t you?”).

With this in mind, I had no interest in writing an “issue book” where that kind of script would be reinforced unquestioningly. I wanted to show what an experience of “mental illness” can look like from the inside out. And I wanted readers to be able to see Kiri’s experience through all sorts of lenses—grief, family breakdown, reaction to living in a world full of yoga condos—rather than saying “look, she has brain-diabetes and once she takes the pills it will all be okay!”

We have talked a fair amount about our mutual discomfort with the identity of Young Adult Writer as opposed to just, like, Writer. Now that the book is out, how are you negotiating the multiple identities of Hilary T. Smith? Do you think you'll keep writing YA?

"Negotiating the multiple identities" is such a graceful way of putting it. For me, it's been more like lurching. Blogging-wise, I've felt torn between a desire to write what I want, and a perverse sense of loyalty to readers both real and imagined who “expect” me to keep writing as INTERN, or as a squeaky-clean YA writer version thereof. I've "negotiated" that tension by more or less going silent. And while I am super stoked about the YA novel I am currently working on, there is a Hilary waiting in the wings who can’t wait to swoop down with some Rikki Ducornet-style novella madness once this contract is finished. I’m an omnivore... so yes, just Writer, please.

And yes, there are frustrations to having your book categorized as a YA novel instead as opposed to just a novel novel. It’s going to get packaged, promoted, reviewed and consumed in a way that suggests it is less “serious” than other books. Nobody would e-mail an "adult" literary fiction author asking for some "fun swag" for a Cupcake Kittens Hot Boys of Summer giveaway, but if you're a female "YA author" that's what you're going to get. Nobody would write an Amazon review complaining that J.D Salinger should have shown more serious consequences for Holden Caulfield’s underaged alcohol use, but a (female) YA author should know better than to let her (female) characters get away with drinking or smoking--I mean, what kind of EXAMPLE is she setting? (It is obviously a female author’s responsibility to set a Good Example for the Children.)

Both of our books deal, in different ways, with some kind of underworld journey, and I am curious what kind of mythology you read growing up--whether it's mythology in the classical sense or a more unorthodox interpretation of the word. Did those stories influence the kinds of stories you wanted to tell as an adult?

I was raised Catholic, so there were always books about saints lying around. For me, the stories about saints were a wonderful initiation into the fantastical--a loaf of bread turns into an armful of roses, a giant carries a boy across a river, people hear voices and see visions and have all sorts of amazing experiences without ever leaving the “real” world.

From a young age, I was used to the idea that one could have a second, stranger and more intense reality superimposed onto the regular one. The characters in the stories I write often reflect this. In Wild Awake, Kiri lives in the real world while simultaneously entering this heightened space where her perceptions are anything but ordinary. I’m interested in the place where consensus reality diverges; where objects and impressions take on a life of their own.

I was reading an article about Rachel Kushner, who wrote The Flamethrowers, a fantastic novel whose lady main character has a lot of particularly epic adventures. Jonathan Franzen (I know, I know, bear with me) had her as a writing student and apparently said of her, "I had the sense that she came from a place where nobody had told young women what they could and couldn't be." Despite the source, that quote's really stuck with me, as someone who was told all throughout my early life that I could be whatever I wanted (which I think my parents might have later come to regret). Both of us have had somewhat unconventional lives, I think, and I am curious as to how you think that's informed your writing.

My parents, and my mother in particular, had an extreme distaste for girly stuff--dance lessons, pink clothes, makeup, the Baby-Sitters' Club. That kind of thing was essentially banned in my house. In some ways I grew up more boy than girl, which caused me a fair amount of grief and social awkwardness in the high-school years but which gave me a sense of independence and agency in the world I now realize has been responsible for pretty much every adventure I’ve had. I now realize that in shielding me from Mattel-syle girl culture when I was a kid, my parents gave me an enormous gift, even if it was a painful one at times.

That sense of agency led me to go on long hitchhiking trips and to seek out strange and occasionally dangerous experiences--because if Jack Kerouac could do it in On the Road, why couldn’t I? That bank of strange, uncomfortable, sometimes luminous experiences has been a huge influence in the kind of books and the kind of characters I want to write.

What are some books you've read recently and loved?

Well, there was this amazing novel called All Our Pretty Songs... [The Editor is blushing.]

July 30, 2013

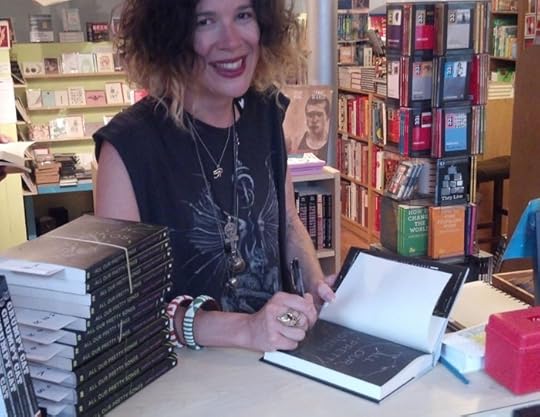

Today

here is me signing books at Word bookstore

the first book that I wrote is out in the world and you can go and get it, if you would like.

If you are in New York you are invited to the launch party at Word bookstore in Brooklyn and you are also invited to a reading for Glamour magazine at McNally Jackson with me and some other very fine people. And if you want to know what you are getting yourself into before you buy anything you can read an excerpt of the book online at Tor.com and in the free digital issue of Glamour.

I am so grateful to all of you, those of you who just started reading and those of you who keep coming back and especially those of you who have been reading this blog since its very beginning, those of you who started out as readers and ended up as friends; you cannot even imagine how much your love and support and kind words and emails have meant to me, or how much they have kept me going when all I wanted to do was put my tail between my legs and go home. Wherever you are now on the path to your own wildest ambitions, there is a slightly feral super belligerent not-so-young-anymore lady in New York cheering like hell for you. Goddammit, there's something in my eye.

xoxosarah

July 22, 2013

A Conversation with Stephanie Kuehn

Stephanie Kuehn is the author of the gorgeous and heartbreaking novel Charm & Strange, a fantastically original story about the monsters we carry with us and the monsters we become, and which has received rave reviews from Kirkus, SLJ, Publishers Weekly, and me, among others.

Charm & Strange is a book about trauma and memory and monsters, and I loved the way the structure of the book mimics the complexity and layers of the story itself. Did you always know you'd tell the story the way that you did?

Yes, the way the story is structured is part of the reason I wanted to tell it in the first place. It’s a narrative structure that allowed me to weave themes of matter and antimatter, quarks, wolves, chemical bonds, chemical breakdowns, and Wittgenstein’s private language argument, into a short, dark story about the impact of trauma and the resilience of the human mind.

Win is an extremely believable teenage narrator, which means he also has ideas about gender and how to be a man that are sometimes pretty ugly. Was it challenging for you as a writer to keep yourself from making Win more "likable" and less real?

If anything, I probably erred on the side of making Win more caustic than necessary. At the time the story begins, he's stuck in a holding pattern of destroying his personal relationships and destroying himself. He’s angry and resentful and scared, and I wanted those qualities to shine through. Being in his head isn’t a likable place, but this is somewhat of the point: Win’s suffering isn’t romantic or noble, and not being likable doesn’t make him a bad person. He’s worthy of compassion and care, not in spite of his difficult personality, but because of his humanity.

Thinking about it more, I find likability a strange concept. I don’t understand what role it plays in storytelling. Is Max from Where the Wild Things Are likable? Or is he relatable in his savage and beastly feelings? Win’s a guy who feels as if he’s the only person on earth who experiences the world the way that he does. While his reality is all his own, his sense of psychic isolation is the emotional essence of adolescence (at least it was for me), and so even in his ugliness, he’s relatable.

The book goes to some dark places, but ultimately (for me at least) ends on a hopeful note. What kinds of stories give you hope in dark times?

I gravitate toward stories that are dark. I don’t know that I connect with much else. But I avoid stories with too much cynicism or righteousness. These are forces I find darker than most.

Werewolves start out as one kind of monster at the beginning of the book, and become a very different kind of monster by the end. Why werewolves--for you as a writer and for Win as a character?

When I was growing up, I read and watched every horror book and film out there. This was in the eighties, which was really the horror heyday, and I don’t know, I was one of those creepy kids who liked animals more than people (myself included), so I was drawn to all the transformation stories. Wolfen. Cat People. Altered States. The Wolf’s Hour. There was even a tv show on Fox called Werewolf that I loved, mostly for the Rick Baker special effects (plus the bloody pentagrams!). I think stories like these fulfill the desire to walk as close to one’s own darkness as possible, and as a teenager, that was one of the strongest desires I had. However, as I got older, as tends to happen, the reality of where true darkness lives and what it looks like became more obvious. And more frightening.

Win’s journey is sort of the opposite. He’s closer to darkness, his own and others, than any young person should be. Because of this, he uses his magic, the wolves, as a way to hold onto both his innocence and his sanity. In this way, he is both very strong and very stuck.

What kinds of stories did you read as a kid? What are some books you've read lately and loved?

As a kid, I vacillated between reading animal and detective stories (The Black Stallion series, Albert Payson Terhune and the Sunnybank collies, Trixie Belden, Three Investigators) and horror novels (a few favorites: Shadowland, Burnt Offerings, The House Next Door, The Amityville Horror, The Fury, The Other, Neverland, Summer of Night, The Butterfly Revolution, Willard, The Little Girl Who Lives Down the Lane, all those Alfred Hitchcock anthologies). Some of my recent favorites are Citrus County by John Brandon, Black Helicopters by Blythe Woolston, Everybody Sees the Ants by A.S. King, and Nothing by Janne Teller.

July 16, 2013

A Conversation with Bennett Madison

Bennett Madison is the author of The Blonde of the Joke and September Girls, a pop-punk remix of The Little Mermaid that's equal parts dreamy beach read and wicked sharp commentary on sex, gender, and growing up (and which I cannot recommend highly enough). He's also very clever, as you will shortly discover.

You’ve said elsewhere that it took you a long time to write this book—did you have any idea what you were getting into when you started it? Did you sit down to write a radical and complex subversion of The Little Mermaid or were you like “Okay, cool, gonna write a nice summer beachy read” and then September Girls happened?

Well, the thing that happened with September Girls is that I was already under contract and I was working on a book that wasn't September Girls. It was not going well and I got into real trouble; I mean, that book came really close to really ruining my life.

That book was called Apocalypse Blonde and it was supposed to sort of be a loose follow-up to my last book, The Blonde of the Joke. It was about just about a bunch of kids lying around by the pool getting drunk, smoking cigarettes and waiting for the end of the world, which they had a vague sense was on the way. While I loved (and still love) what I'd written of it, I got about halfway through and hit a major wall. It was both too simple and too complicated and while I was amusing myself, it didn't really have anything driving it to a conclusion.

Meanwhile, it was really late to my publisher and I was living temporarily with my parents while I tried to finish it. I was completely out of money, and every day I would have a new solution on how to fix it. You know, the kind of solution that's like, "Maybe I should rewrite the entire book from page one from a totally different character's perspective." You know you're in trouble when you start thinking like that. None of it worked;it was just pulling me further and further into it in a really discouraging and quicksandy way.

So when I was talking to a friend and came up with the idea for September Girls sort of as a half-joke, it only took me like a couple of hours to realize that I should just switch gears and jump right into it. I called my editor that day and told her I was starting over. She seemed skeptical but also open to the idea.

Part of the initial appeal of September Girls was that I could sort of see most of the major beats of the story from the outset. It seemed like it wouldn't take that long to write, and like I wouldn't get stuck in the weeds the way I had with Apocalypse Blonde.

I wanted to write something beachy and summery and light, but definitely something complex and weird and subversive too, because that's just what I'm into. At a certain point several months later, I did start to feel like I'd bitten off more than I could chew again. There were times during writing it when I started getting really tripped up because certain necessities of the plot were leading me in a direction where I wondered if I was saying something I didn't want to be saying. It took a really long time to sort all that out and untangle it.

Plus, it ended up being really hard for me to write a love story. Attraction is so hard to articulate, and I think I made it even harder for myself because I wanted this to be a weird kind of love story where the characters' attraction to each other was sort of beside the point.

One night while eating dinner with my parents I made a joke about The Shining and my mom gave my dad a look that was like, shit, we were worried this was a Shining situation.

So basically, yes, I started it because I thought it would be easy, and while it wasn't easy, it was definitely easier than the book I'd been writing. (I would probably still be working on that one if I hadn't thrown it away when I did.) And I narrowly avoided going completely insane, although I probably did come pretty close.

One thing that’s interesting to me as both a writer and a reader is the totally disparate ways in which many readers and online reviewers react to books that are marketed as YA as opposed to “adult” fiction--a moral panic that’s usually applied to books with female teen narrators, so congratulations, I guess, on breaking the mold. Do you think September Girls would have provoked the same anxieties over Sam’s frank discussion of his sexuality (which, for the record, I found hilarious, endearing, relatable, and totally real) if the book had been marketed to adults? And if not, do you have any theories as to why?

It's a tough question. No one has really settled yet on the definition of what YA even really is, or on what separates it from "adult" fiction. Even among YA authors, there doesn't seem to be a strong consensus about this. I tend to just consider it a marketing category, but other authors I know think that there are different "rules" for teen fiction--that it has a set of conventions and aims all of its own.

There are also all these questions of influence when it comes to YA that I don't think are asked (or asked nearly as much) about books marketed to grown-ups. Do YA writers bear an added responsibility to educate or inspire because our books are aimed at younger readers? Are there ideas and themes and language that can be dangerous to our readers, who (some would argue) might not have the capacity to understand it?

These questions hinge, to me, on what's an essentially false premise: that adults are going to think critically about a book while teenagers will sort of just receive it unquestioningly. I don't think that's true at all--to me, teenagers are just as critical as any other readers. Maybe more critical.

Personally, I don't think a ton about the fact that I'm writing for a YA audience while I'm writing. I just try to write the book I want to write. Anyway, I'm not sure there's a huge difference between teen books and adult books in terms of the actual readership, at least not these days. Adults read YA and teenagers read adult books, so it's like, who cares? Especially when it comes to books like mine, which are pretty clearly for an older teen audience.

Even so, I wasn't totally surprised that there's been some controversy around the book, because I think it's a weird book that maybe is at odds with people's expectations. Nothing makes people madder than having their expectations confounded.

I think the thing that the publishing industry has done really, really well in the last ten years is that they've been able to present YA books as entertainment. This is in a lot of ways great. It's a big part, I think, of why YA has been selling really well, and why so many adults are turning to YA. People want to be entertained, and adult literary books--even when they're super-entertaining!--have for so long been pitched to the public as difficult but good-for-you. Like an eat your spinach kind of thing. YA, because of the way it's marketed, doesn't seem as scary. People pick it up more easily, because it's not as intimidating.

This is great in a lot of ways. It means sales! But the one bad thing about it is that readers can sometimes get upset when they come to a book looking for a really breezy read and it ends up not being so breezy. I think that happened to some extent with September Girls --people were thinking, this isn't what I thought I was signing up for. I don't know that there's a lot I can do about that, but I've certainly thought about it.

It's hard to know how people would have responded to the book if it had been officially aimed at an adult audience. I do think that a lot of the sex stuff--which is really fairly mild--is probably more shocking in the context of a "teen" book. But I also think that the really strong reaction also has to do with the way the internet has changed in the last few years. Controversies become memes much more quickly than they used to; they take on a life of their own. I guess it's probably a good thing in the end, but I wasn't so prepared for it.

Traditional ideas of gender are huge barriers for most of the characters in September Girls --Dee Dee recognizes that she’s going to be the “ho” in any story told about her; the Girls are literally unable to leave the beach; Sam’s dad, brother, and best friend all have difficulty building actual relationships with women because of their varying degrees of misogyny; and Sam understands that the men around him aren’t exactly ideal role models but he doesn’t have the tools at the beginning of the book to figure out a different way of being in the world. Technically, that’s not a question. But I wonder if you could talk about gender and how it gets constructed and deconstructed in the book.

I came up with the idea for September Girls when I was having a discussion with my friend Bob Berens about Twilight. I think we were talking about the way virginity and abstinence operates in those books. On a practical level it's a story complication: Bella and Edward can't have sex because she'll become a vampire if they do, so it's part of the romantic push-pull thing, where the characters who are supposed to be together can't be together. But it's also a thematic concern: Bella's supposed "purity" is part of what makes her special. It's part of her magic. We see these tropes a lot, not just in Twilight.

I wanted to see what happened when the poles of that story were flipped--for it to be the boy who's the Magical Virgin and the girl who's the Magical Lothario. I really had no idea what that reversal would lead to; I just thought it would be interesting to work with.

On top of that, I knew I wanted a boy protagonist who stymied some of the stereotypes about male sexuality. There's this idea that boys always want sex and girls have to be pushed into it, and in my experience, that's just not the way it works a lot of the time. Sex can be really scary and stressful for guys--there's pressure to perform, pressure to be macho, to be the aggressor and know exactly what you're doing, to have the biggest dick. I wanted to show all that that, and I wanted to show how all these expectations about manhood and what masculinity entails are both a consequence of patriarchy and something that ends up perpetuating it. Patriarchy harms both men and women, and in doing so, it feeds itself.

Obviously The Little Mermaid was on my mind a lot too. In both the Disney version and the original Hans Christian Andersen version, the mermaid's only chance for survival is to make the prince fall in love with her.

I realize there's a lot of other stuff going on in the story too, and that what it all means can be interpreted in a lot of different ways. But I was interested in it in a sort of acontextual way--or at least in the story as something independent from the original text. And when I think about The Little Mermaid, I can't help coming back to the whole seduce or die thing.

So many mermaid (and "mermaid-adjacent") myths revolve around seduction and the danger of female sexual power. Sometimes the mermaid (or Siren, or Rusalka) is cast as a femme fatale; in other stories she's turned into a sex object and then imprisoned or punished because of it. Either way, there tends to be a degree of misogyny in the most traditional sense--mermaid stories are about fear of female sexuality as well as a desire to tame and control it.

It was important to me in September Girls to confront those things, as well as show that they're two sides of the same coin rather than opposites. The Rapture, as the mermaids are called in my book, use sex and seduction as a survival tool and a weapon, but they're trapped by their sexuality too. They seem to understand that the world wants them to be objects and rather than fight that, they're trying to use it to their advantage. How effective is that for them? It's like all those old arguments about stripping, or the arguments about what they were briefly calling "do-me feminism." When are you gaming the system and when are you buying further into it?

These are really tough questions, and there was absolutely a point while I was writing the book that I started to get concerned about that they were too complicated for me to grapple with in the way I wanted to--especially because I'm a man. Was I deconstructing patriarchal structures or was I just replicating them?

In the end, I decided that I had to be okay with some ambiguity. I mean, that's part of what I love about the way fiction functions. Fiction doesn't have to make an airtight argument. Fiction can raise questions without always having the answers; it can ask readers to make abstract connections and approach things from sideways angles. In the end I wanted the reader to be thinking about what's problematic in the story.

Even so, I couldn't help worrying that the Girls were being punished in an unrelenting way--that, even if I had the best intentions, I was creating torture-porn disguised as critique. Because of that worry, I ultimately decided it was important that there be at least one character who beats the system and wins on her own terms, but in an unexpected and not straightforward way. I don't want to say which character it is, and I do think it's very possible to miss it, but--by my reading at least--one character in the book cracks the code in a way that the others don't. (I point this out because I don't think I've seen anyone mention this character or her fate much.)

September Girls is stunning and fresh and not remotely derivative, but at the same time, it had a total nineties vibe for me--there’s something about its aesthetics and language, its seamless mashup of the real and the surreal, pop culture and mythology, that brought to mind Weetzie Bat and Emma Donoghue’s Kissing the Witch (and, inexplicably, Blake Nelson’s Girl, and Bett Williams's criminally under-read Girl Walking Backwards, maybe because it deals with sex so openly? I honestly don’t know entirely). I’m curious if that reading seems accurate to you or way off the mark. The poetics of the Great Nineties Adolescence Novel? Is that a thing? Do you have feelings about it?

Thank you! Weetzie Bat is one of the most important books I've ever read for so many reasons that it's hard to even articulate all of them. And I still remember reading that excerpt from Girl in Sassy and being completely blown away and inspired by it. So I am very flattered to be compared to those things. (I will definitely have to read Girl Walking Backwards.)

One prevailing attitude during that time, which I think a lot of my characters share, is this kind of jaded optimism. I think my characters have that too, but perhaps it's maybe in contrast to some other YA characters these days, who are often more straightforwardly decent and accessible. Not that there's anything wrong with that!

We talk about irony and sincerity as opposing forces now, but when you look at pop culture in the '90s--Nirvana, the Riot Grrrls, the Brady Bunch Movie, Sassy magazine, zines in the vein of Teenage Gang Debs, etc.--so much of it was about using irony as a rhetorical tool to say something really sincere and deeply felt. They were being funny, but that didn't mean they weren't being serious. And I sort of think that my taste and style was sort of inspired by that. I refuse to accept that irony is dead, or that we live in an age of sincerity. Can't we have both?

It also seems to me like the '90s were when postmodernism really became part of the mainstream aesthetic. There was all this playful juxtaposition, all this mixing of genre and of high and low. Everyone seemed to be doing this sort of collagist thing. I would add Neil Gaiman to your list too--he may be more famous than ever these days, but he was definitely mixing things up in a really important way with Sandman. [GOOD CALL. --ed.] I was certainly soaking all of it up.

What did you read as a kid? What are you reading now?

I read so much stuff as a little kid--I mean, I read everything. I was always getting in trouble for reading too much, because when I was really little I did it at the expense of everything else. I loved Narnia, Prydain, Pippi Longstocking, Roald Dahl, Lois Lowry's Anastasia [ANASTASIA KRUPNIK!!!!!!!! --ed.], the Great Brain books, plus a bunch of other stuff I barely remember. The Girl With the Silver Eyes. Oddball stuff that maybe only I remember, like Elizabeth Enright's Melendy series. Edward Eager. For awhile I just read everything I could get my hands on.

I had a couple of real, true obsessions though: first, I was obsessed with L. Frank Baum's Oz books, of which there are secretly a zillion. (Other people took over the series after he died, and they kept being written well into the 40's. Maybe the '50s?) When I finally got bored of those, I moved on to The Baby-Sitter's Club. Although obviously a lot of probably true things can be said about why a little boy would be begging his parents to drive him to the bookstore on the first of every month to buy the newest BSC book, I think my love for the BSC had a lot in common with my Oz thing. Both series gave you a huge fictional world that had tons and tons of colorful characters and not that much else going on. The lack of any particularly compelling plot actually just meant that these worlds were your imaginary toy boxes. You could spend a lot of time moving the characters around on your own.For a dreamy child who spent most of his days not paying attention in class, this was very important.

At a certain point it got embarrassing so I got sick of books for awhile and discovered the X-Men, who I think held a very similar appeal, along with a bunch of extremely fun coded gay subtext.

As for these days:

I just finished reading my friend Filip Noterdaeme's T The Autobiography of Daniel J. Isengart. Filip's a very genius artist who, in the spirit of Gertrude Stein, decided to write memoir on behalf of his longtime boyfriend. I know that doesn't necessarily sound immediately appealing, but the book is charming and hilarious and gossipy in addition to being a pretty searing critique of the dumb art world.

Oh, and I just got around to reading The Family Fang, which I thought was super-funny. And the new Heidi Julavits book, The Vanishers, which I really liked a lot even though the experience of reading it was sort of unpleasant. (Purposefully, I think.) The Woman Upstairs was obviously great, although I didn't think it was as outrageously fun as The Emperor's Children. My favorite book that from the last few years was Skippy Dies. It seemed like it had somehow been engineered to appeal to all my personal interests.

I haven't read as much YA this year as I should have; I'm just behind on it. But I really enjoyed Erica Lorraine Scheidt's Uses for Boys and I'm looking forward to Natalie Standiford's The Boy on the Bridge and Anna Jarzab's Tandem and probably a bunch of other stuff I'm forgetting.

July 9, 2013

Some Books I Have Been Reading Lately And Some Other Books I Am Going to Read

Bennett Madison

The September Girls

342pp. Harper Teen.

9780061255632

So like imagine that there was someone genius enough to mash up a wicked smart fairytale reboot, a poignant and wry commentary on the perils of compulsory heteronormativity, a totally baller love story, and a running series of increasingly hilarious Little Mermaid jokes into what is basically the greatest beach read ever except OH SNAP you don't have to imagine because that person is Bennett Madison and HE DID IT. There you go. I loved this book straight up through until the very end, and then the last few pages blew me straight out of the water (DO YOU SEE WHAT I DID THERE) and I went straight from love to just plain awe. Funny and sweet and sad and lovely and all the good things you could ask for in a book; the only bad thing about The September Girls is that it ends.

Susan Choi

My Education

304pp. Viking.

9780670024902

I have been a fan of Susan Choi since I read her utterly stunning American Woman, and My Education is a book from a writer at the pinnacle of her game. I live-texted half this book to my bestie as I read it--seriously, there are sentences in here so fantastic I wanted to tattoo them on my person. A little bit love story, a little bit coming-of-age story, a little bit meditation on the amazing, hilarious, and gut-wrenching mess human beings make out of our dealings with one another, and a whole lot of perfect. Also, special bonus, one of the hottest sex scenes ever written in the history of sex scenes. AND a delicious twist of an ending that you will totally never see coming (well, I didn't, anyway) and yet is the most exact right ending imaginable. Why are you listening to me babble, just go read it.

Sara Gran

Claire DeWitt and the Bohemian Highway

288pp. Houghton Mifflin.

9780547429335

If you have not yet read Sara Gran's first installment in the Claire DeWitt series, Claire DeWitt and the City of the Dead, then I am very thrilled for you, because the delights that await you are in fact unparalleled. Like its predecessor, genre-upending Claire DeWitt and the Bohemian Highway is lethally smart and wildly funny, but it is also, by the end, a totally gorgeous heartbreak of a book that left me unabashedly bawling my head off on the Q train. If you are a person anything like me you will see rather more of yourself than might be entirely comfortable in cranky, misanthropic, and wounded Claire, but you do not need to find Sara Gran's magnificently unpredictable heroine eminently relatable in order to appreciate the stunning brilliance of this book. Hard to believe such a thing is possible, but it's even better than the first one.

Hilary T. Smith

Wild Awake

375pp. Katherine Tegen.

9780062184689

If you have so much as looked at Hilary Smith's hilarious and much-beloved blog, it will come as no surprise to you that her first novel is as lovely and sharp and brilliant a book as a person could wish for. The story of a young aspiring concert pianist whose quiet summer housesitting for her parents is suddenly derailed into a perilous search for the truth about what happened to her dead sister, Wild Awake is a rich and compelling journey through grief, loss, madness, illness, music, and, ultimately, love. Smith is a hugely talented and huge-hearted writer, and Wild Awake is a magnificent debut.

Lisa Brackmann

Hour of the Rat

371pp. Soho Crime.

9781616952341

I am a great big fan of Lisa Brackmann, who has a rare knack for turning out smartly-crafted and addictive thrillers that are as politically astute as they are fun to read, and her latest (starring the irrepressible and routinely unlucky Ellie McEnroe of Rock Paper Tiger) is no exception. Ellie is, no surprise, in trouble again: an old Army buddy enlists her to track down his missing brother in China, a job that turns out to have some serious complications. Fans of Ellie will be pleased to see her judgment remains dubious, her heart remains true, and her ability to get herself into as much hot water as possible at any given moment remains unerring.

And some new and upcoming books I am excited about: brilliant essayist Kiese Laymon's much-acclaimed first novel Long Division; Katie Coyle's prize-winning YA debut Vivian Versus the Apocalypse (you can, and should, because they are excellent, read the first few pages online here); and Kari Luna's first novel, The Theory of Everything.

Sarah McCarry's Blog

- Sarah McCarry's profile

- 155 followers