Sarah McCarry's Blog, page 4

January 5, 2015

all the books i read in barcelona

In Barcelona I tried hard not to think too hard about anything and mostly it worked.

Beers in the early afternoon and long walks around the old city and every day was sunny and warm enough in the afternoon for an hour or so to take your coat off and sit in the clear quiet light. The only things I can say in Spanish are “please” and “thank you” and “I have to pee” and so I did a lot of pointing. After eight days in Barcelona I can also say “ham sandwich” and “fried peppers.” Next on my list of things to do is learn Spanish but it is a useful and disorienting and humbling experience for someone whose whole life is language to spend time in a new place without the ability to speak.

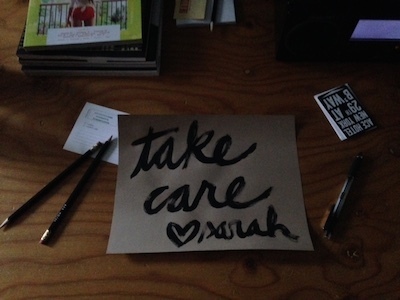

My boyfriend left a chapbook on my pillow every morning in Barcelona, which is a very romantic thing to do if you are dating a writer who also publishes chapbooks, or a reader, or dating anyone at all really, and I have been thinking about different ways of writing about what I read. Reviewing books is one way of meeting them on their own terms but the labor of a review is a certain kind of work I do not always feel like performing, because the way I read most of the time is out of selfishness. I do not believe that it is possible to write objectively about anything at all but a review should at least move toward the book instead of lie about eating chocolate and wondering whether it is too early to drink another beer. A review should ask what a book is doing in relation to its own ambitions and when I write about books I like to ask what the book is doing in relation to myself. I read books that do not ask much of me when I am sad and books that make me work harder when I am happy, or chipping away at something of my own, or on the days I take the train an hour and a half each way to my day job as a way of saying Here is work I did for myself instead of other people. And as it turns out the chapbook is a perfect form for someone struggling to navigate a city in which she cannot even manage to utter a sentence, in which she is eternally lost; a city for which she did not even think to bring a map. This kind of thinking, this kind of travel: something that is focused and sharp but also ephemeral and easy to carry.

My boyfriend left me two Ker-Bloom!

zines without having any idea that I’ve read that zine off and on for years. The woman who makes it has a child now and has left one city and moved back again and everybody is getting older but still also doing what they love and that’s reassuring. Here we are, trucking along, making things. Also: May-Lan Tan’s Girly , which is published by Future Tense, a press you should be paying attention to because they also put out Chelsea Hodson’s chapbook Pity the Animal, which is brilliant, and Wendy Ortiz’s memoir Excavation, which is brilliant too, and Girly was so good that as soon as I finished it I ordered her book even though it has to come from England and the postage is expensive and I have about four hundred books at home I am supposed to read first. Also: Bhanu Kapil’s Treinte Ban (A+ boyfriend, I know) which I read twice in a row and is about a lot of things but one of them is about writing a thing that does not want to be written and for which there is not yet an adequate form, and lucky me the book I am writing now is a thing like that, which is not a thing I would have picked to write had I known in advance but if it was easy it wouldn’t be art. It might not be art anyway but I am trying to be optimistic.

We found La Central by accident, which you think at first is just a little design-y bookshop and then turns out to unfold in a vast extraordinary maze, one room after another and then more floors and more rooms and more and more and more, like the kind of bookstores that happen sometimes in your dreams. I bought Susan Sontag’s Illness As Metaphor there because I am also chipping away at an essay about vampires and cancer and I had a feeling that Susan Sontag would be a lot smarter than I am about cancer, and I turned out to be right, but that’s okay. Also Juliet Escoria’s Black Cloud, which is bleak and precise and great if you like fucked-up stories about fucked-up girls doing fucked-up things, which I do.

I brought The Unabridged Journals of Sylvia Plath with me from home and read a little bit of that too and found the magnificent pretentiousness of the adolescent Sylvia Plath a little too close for comfort, considering the last time I read the unabridged journals of Sylvia Plath I was myself barely no longer adolescent and felt deeply that she had spoken the very language of my core. And I also brought with me The Light of Truth, a collection of the writing of Ida B. Wells, which is fierce and beautiful and depressingly as relevant now as it was when it was written. I meant to read more on the plane ride home but I watched a lot of terrible movies instead. That one about the little boys running around in a maze in henleys and the one where Tom Cruise keeps dying and one more that was so bad I don’t even remember it at all, and now I am home and can talk again, but I still don’t feel much like thinking.

December 22, 2014

solstice

Last night I had a one-night residency at the Ace, a Portland-themed hotel in Midtown. (The whole hotel is plastered with slogans in a knowingly folksy tone, and it is like being followed everywhere by a twenty-five-year-old Wieden + Kennedy employee in a beanie and Filson shirt nattering on at you, but if you don’t have quite the baggage I do with Portland I’m sure it’s all very witty and charming. In all other respects it’s a lovely hotel.)

In the spirit of my hotel residency I thought I would spend Sunday afternoon pretending to be a tourist—maybe buy a map and wander about with a bewildered expression running into people and photographing myself on random street corners—but my dignity is tremendously important to me and anyway the day got away from me. But I did forget what street the Ace was on, and wound up walking four blocks in the wrong direction, and so I was disoriented after all when I arrived; and there is something wonderfully lonely and strange about hotel rooms, something about the light and the emptiness and the way as soon as you cross the threshold you feel yourself all at once to be on the verge of becoming someone other than the person you ordinarily are, a traveler or an anthropologist, so that even a hotel room in city where you have lived for years is a kind of passageway into another country.

The Ace is only a few blocks from the office where I once worked for a literary agent, the office where one slow afternoon I started this blog. I used to come to the coffee shop in the lobby every day until all the baristas knew me, although none of the people I befriended have worked at that coffee shop for a long time now. I was so broke then and all my clothes were shabby and it felt as though the future was an increasingly bleak landscape I had little wish to traverse. I did not know that my life was already changing. It is impossible to see those moments for what they are until you are in a position to look back on them, but of course the catch is that it is difficult, when you are in the thick of despair, to imagine that someday you might be past it. The literary agent got me a meeting with an editor who didn’t have a job for me but might know someone who knew someone who knew someone who did, and I sat in his office and looked at all the shelves lined with all the excellent books he had edited, many of which I’d read and liked, and when he asked me what I wanted to do I said Well actually I want to be a writer and he said Why in god’s name are you trying to get a job in publishing then, get out of here and go work in a bar. As it turned out that would be the best advice anybody in publishing ever gave me. It took me a while too see that, too.

Last night was also the winter solstice, with a new moon in Capricorn no less, which means, if you are the kind of person who puts stock in such things, that now is a time not just for planting seeds but also preparing the earth for them, for the labor of both dreaming dreams and making room for their fruition; and if you are not the kind of person who puts stock in such things, that’s good advice anyway. Last night I read my new favorite astrologer, Chani Nicholas, who in addition to being a fine astrologer also has the habit of dropping revolutionary science into her horoscopes—“Reviewing your relationship to power and to how you might perpetuate dominance is apt to be high on the agenda right now”—and who does not shy away from what is happening in the world around us. It is a relief to have it acknowledged that the body with which you plan for your future and go to your day job and think about what you will eat next is also the body with which you write about trauma and loss and light candles to remind yourself of the value of hope, which is not the same thing as optimism. That we can allow ourselves to turn inward, to take the long night for rest and regeneration and making space for the possible, but we are also called to name injustice, to refuse to turn away.

The lessons of the solstice are obvious but sometimes we need obvious lessons. Renewal, letting go of unnecessary burdens. Hope. The longest night is the best night for dreaming; when the morning comes at last, get to work. Last night I went to the hotel gym, scaring the wits out of a gentle-faced man taking out his frustrations on the hotel-gym boxing bag, and ate dinner at a weirdly branded salad bar, too-brightly lit and plastered with meaningless motivational slogans (LIVE BEAUTIFULLY). Afterward I drank my complimentary artist’s whiskey in the Ace lobby and wrote in my notebook and thought about how I had come full circle, quite literally, to the same place I had started in this city, but as a person so different that it was as though I was visiting some new city altogether. But of course that's not exactly true. I am still always and only myself. The city is only ever the city. Any point in your life can become a symbol if you want it to, but it was hard not to read the place I found myself last night as a recognition of all the work I had done to get there, and all the work there is still left to do. Maybe that was just the whiskey.

This morning I woke up early enough to walk the forty or so blocks to my day job, feeling like myself again: less shabby, hopeful, making lists of things to do. Outside the sky is a smeary headache-colored grey that does little to encourage faith in the lengthening of the days, or much else for that matter; but then again, that’s what faith is. Trusting, against all evidence, that the light will return.

December 2, 2014

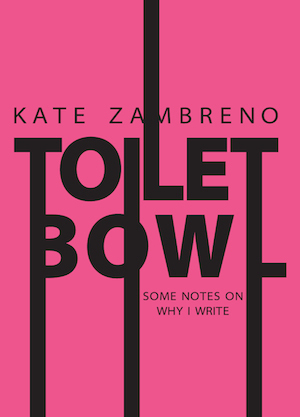

Kate Zambreno Reprint & Guillotine Backlist Sale

A girl is a gun. A woman is a bomb.

Kate Zambreno's sold-out Guillotine chapbook is finally back in print! You can order it now.

BACKLIST SALE: From now through the end of December, get Troubleshooting Silence in Arizona, [Censorship & Homophobia], and For Love or Money for just $25.

November 26, 2014

last night

Yesterday was unseasonably warm and today too and tomorrow it's supposed to snow, and I have to get up earlier than a person should in order to collect cupcakes for a party at my day job and transport them across two avenue blocks and ten regular blocks of sleet and misery.

It is hard to think about anything other than broken hearts and a broken world after the last couple of days, but I'm trying. I don't drink as much as I used to because when you are a person—let us say, euphemistically, of a melancholic disposition, who is not getting any younger—drinking too much is usually a proposition that ends in soul-crushing disaster and a night that is too dark and too long and too full of questions about all the times you fucked up previously and all the times you will doubtless fuck up again, but sometimes you are meeting new friends for the first time and everything seems again, suddenly, as though it might be full of possibility despite the crash and burn of the world you love and live in, and you come home tipsy and put on doom metal and the cat hides in a closet while you think about how maybe really the decisions you made were good ones because they got you to the place that you are. The best kind of tipsy, the kind of tipsy that is rare and full of quiet joy that lasts through until the morning. Deep breath, back straight: the necessary labor of helping to carry a bright torch in a darkening world.

In the middle of a bleak place without hope it's been a day of small triumphs, and I will have good things to share with you soon, and there are exciting things coming up for Guillotine that I can tell you about soon too, and the cat will get over the doom metal, and now I'm going to eat some ramen and go to bed early so I can get up early to carry the cupcakes through the snow. I got the final pass pages back for About A Girl and I have been reading through it and realizing, to my surprise, that it is a book of which I am quite proud. Last night I went to see A Girl Walks Home Alone At Night and it was exactly what I wanted it to be, lovely and funny and sly and sad, and filled with moments of a beauty so perfectly rendered it left me stunned, and when I came out of the theater I gave myself the luxury of not checking the news for a moment so that I could spend a little longer in its world before this world descended on me, before I cried on the train on the way home because—well, you know why. I don’t have anything worth saying about that but Roxane does and you should read her instead.

But I remembered again, tonight, for the thousandth time, that love is all we have left to carry us, and love is what I have to give. And it doesn't seem like ordinary things ought to keep going but they do and sometimes the movement of ordinary things is the only thing keeping us going and so it does. I don’t celebrate Thanksgiving for reasons that I hope are obvious and so I will spend this weekend working instead, and thinking about love, the kind of love that is a choice to demand a better world to house it. A love that insists on seeing, on not looking away. A love of making work and the work of loving against the odds and the work of holding some kind of faith that a future is a place we want to get to, that a future can be something other than the thing we are looking at now. That all the pieces of our shattered hearts knit together can make a thing that is almost whole. Living for the fight, as they say, since it’s all that we’ve got.

November 5, 2014

it's here!

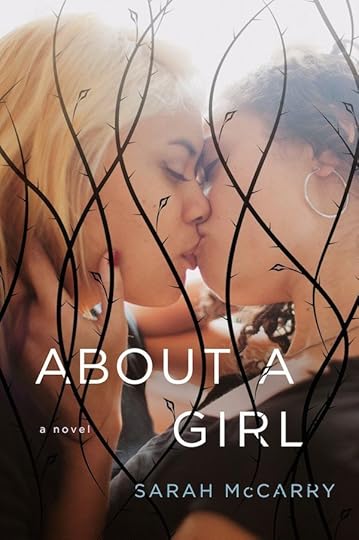

Belatedly: the cover of About A Girl is live! (Or: That Time My Friends Made Out For The Betterment of Humanity.) I am so happy, and so proud, and so grateful to have worked with photographer Sandy Honig, cover models Lola Pellegrino and Kimmie David, St. Martin's designer Elsie Lyons, and everyone at St. Martin's who made this cover possible. More about the process behind the cover here; thank you to the many, many people who were as excited as I was to see this (FINALLY) happen.

October 22, 2014

About A Girl: An Excerpt

My third book, About A Girl, comes out next summer, and, like all of my books thus far, is about love and death and magic and growing up. This one is also about astronomy and Medea and a little town on the Olympic Peninsula where I used to live a long time ago, and it is really, really gay. On Monday the whole world will get to see its cover; in the meantime, here’s a little taste of the book:

“Tonight is my eighteenth birthday party and the beginning of the rest of my life, which I have already ruined; but before I describe how I arrived at calamity I will have to explain to you something of my personal history, which is, as you might expect, complicated—

If you will excuse me for a moment, someone has just come into the bookstore—No, we do not carry the latest craze in diet cookbooks—and thus she has departed again, leaving me in peace upon my stool at the cash register, where I shall detail the particulars that have led me to this moment of crisis.

In 1969, the Caltech physicist Murray Gell-Mann—theorist and christener of the quark, bird-watcher, and famed perfectionist—was awarded the Nobel Prize for his contributions to the field of particle physics. In his acceptance speech, he referenced the ostensibly more modest remark by Isaac Newton that if he had seen farther than others it was because he stood on the shoulders of giants, commenting that if he, Murray Gell-Mann, was better able to view the horizon, it was because he was surrounded by dwarfs. (Newton himself was referring rather unkindly to his detested rival Robert Hooke, who was a person of uncommonly small stature, so it’s possible Gell-Mann was making an elaborate joke.) While I am more inclined to a certain degree of humility in public, I find myself not unsympathetic to his position. I am considered precocious, for good reason. Some people might say insufferable, but I do not truck with fools. (“What you’re doing is good,” Murray Gell-Mann told his colleague Sheldon Glashow, “but people will be very stupid about it.” Glashow went on to win the Nobel Prize himself.)

—What? Well, of course we have Lolita, although I don’t think that’s the sort of book high-school teachers are equipped to teach—No, it’s not that it’s dirty exactly, it’s just—Yes, I did see the movie—Sixteen-eleven, thanks—Cards, sure. Okay, goodbye, enjoy your summer; there is nothing that makes me so glad to have escaped high school as teenagers—

My name is Atalanta, and I am going to be an astronomer, if one’s inclination is toward the romantic and nonspecific. My own inclination is neither, as I am a scientist. I am interested in dark energy, but less so in theoretical physics; it is time at the telescope that calls to me most strongly—we have telescopes, now, that can see all the way to the earliest hours of the universe, when the cloud of plasma after the Big Bang cooled enough to let light stream out, and it is difficult to imagine anything more thrilling than studying the birth of everything we know to be real. Assuming it is real, but that, of course, is an abstract question, and somewhat tangential to my main points at present. And though much of astronomy is, and has always been, the management of data—the recognition of patterns in vast tables of observations, the ability to pick the secrets of the universe out of spreadsheets thousands of pages long—there are also the lovely sleepless nights in the observatory, the kinship of people driven and obsessed enough to stay up fourteen hours at a stretch in the freezing dark tracking the slow dance of distant stars across the sky; those are the people whose number I should like one day to count myself among.

I am aware that I am only one day shy of eighteen and that I will have time to decide more carefully in what I will specialize as I obtain my doctorate and subsequent research fellowships, and I will be obliged as well to consider the highly competitive nature of the field—which is not, of course, to say that I am unequipped to address its rigors, only that I prefer to do work that has not been done already, the better to make my mark upon the cosmos. At any rate I like telescopes and I like beginnings and I like unanswered questions, and the universe has got plenty of those yet.”

October 1, 2014

fratres

This morning on the B train: listening to Arvo Pärt’s Tabula Rasa, the kind of music that makes you feel as though you have stepped into a movie about your life that is significantly more grand and tragic and freighted with meaning than your actual life, as though you are the sort of person who is also more grand and tragic and freighted with meaning than you actually are.

It’s almost cold out, which no one except me is happy about, but I think of all the long dark nights ahead and walking home through the snow—maybe the first snow of the season, with the city hushing into stillness all around me and the sky suffused with the kind of dense purpled light that only comes with snowfall—back to my cozy, tiny apartment, candles burning among the tendrilly plants that line my windowsill, cat drowsing on the blanket-piled bed. Even when I was younger and went to a great many parties my favorite part of the party was nearly always the part when I went home. I am thinking more and more about monsters because I am not ready yet to write about monsters, because I’ve been circling and circling this monster book, which hunches in the middle of the floor glaring at me red-eyed and slavering, but I have a teetering pile of treatises on monsters now and the most magnificent thing I can imagine at present is a long sleepy Sunday with no one emailing me and nothing to do except listen to doom metal and go through my monster texts; but that day’s a while off yet, because I owe a lot of work to a lot of people and any days off at all are a long way away.

Sometimes I think about the level of labor it takes to live here, and wonder what my life would be like if I went instead somewhere quieter and cheaper, a place where I could write what I wanted to write when and for as long as I wanted to write it; but then I take the train home across the Manhattan bridge at sunset and look out at the rose-gold river and the skyscrapers turning to liquid silver and all the lights of the city glittering and think, still, after all these years, Holy shit I live here, and remember that I am not (maybe never will be) ready to leave. We find our places where we find them, and there is no home that does not come with its own kind of tax on our hearts.

Arvo Pärt came to New York this year, in May—the first time in thirty years, and I would imagine probably the last—and we went to the concert at Carnegie Hall. All through the audience drifted Orthodox priests in their bat-black robes and heavy crosses, moving soundlessly as ghosts between the glittering rows of wealthy people in their concert clothes, and even all the way up in the balcony the air seemed suffused with a very old magic, and from the first note I felt it working its way into my chest and pulling me wide open. I cried all the way through Fratres, the kind of crying that threatens to undo you, which is a lot easier to stealth at a rock show in the dark

than in the middle of Carnegie Hall where it is both unseemly and discourteous to so much as rattle your cough-drop wrapper, but no one got cross with me that I could tell. Afterward Arvo Pärt came onstage and the standing ovation went on for ten minutes, fifteen—he kept trying to make a polite exit and people would only clap harder, until at last he had to mime going to sleep and the audience finally let him go. We were still so caught up in the spell we went to one of those gorgeous and stupidly expensive bars up in that part of town—high ceilings, leaded glass, velvet drapes tumbling down the walls, the kind of light that makes even rich people look lovely. The bartender asked us where we were from and we said Here, and he said Me too, and we all looked at each other and smiled—because, even though, none of us were telling the truth.

September 25, 2014

sleep cycles

Yesterday my coworkers were talking about how they google everyone in the office and I was like Did you google me and they were like Of course and I was like Oh, whoops.

Here I was thinking I could go in in drag, you know, Office Performance Sarah, maybe they’re reading this now, Hi guys. I think you’re great. I was enjoying the ruse of pretending to be a person without opinions who is only vacantly pleasant and makes the coffee but I have been found out. I am forever being found out, it is my lot in life. On Wednesday or Monday or I don’t even remember what day I read that essay about Henry James and wrote a blog post about it on my lunch break, and I guess a lot of people read it—it’s always the things I spend the least amount of time on that the most people read, you would think I would have this figured out after six years of the internet—and someone told me yesterday they [he] always loved a good vitriolic takedown and I wanted to say do you not understand the difference between vitriol and boredom, I have no vitriol left in me other than for rush hour on the Q, I’m just very bored with being told I do not exist, very bored and also very tired. Tired all the way down to my motherfucking bones. Tired like the time I was talking about speculative fiction with someone I respected who makes a lot more money than I do—like a lot more—writing [about men], who told me he never teaches Octavia Butler because she is too polemic and in my whole heart I was done and either you understand why or you don’t, and if you don’t I am thirty-five years old and too motherfucking tired to explain it to you, I have fourteen jobs to work and books of my own to write and I am fine with the time-saving device of On My Side and Not On My Side because back in the day when I was like Everyone Has A Side I spent a lot of time with men who were assholes and these days my dance card is full. Do you understand? Some of you do. I reserve the right to peace the fuck out of a conversation, let’s talk about the weather instead so this party doesn’t get awkward. When you’re like Yeah cool you know it’s just at some point in my life I got really exhausted by narratives in which I was not present, in which my humanity was not even, like, an option, so I don’t read them anymore unless they also involve spaceships or monsters, and you can see it in their faces. She would be almost clever if she weren’t so naive. [She could be fuckable if.] She talks too much but not about the right things. Where did she go to college? Oh. She doesn’t talk at all but you can see contempt writ large across her features. God she's angry, isn't she. Maybe if she wore a dress. She doesn’t register. She is unwilling to see both sides, in particular the side in which she is not actually a person. She is insistent on politicizing the conversation. She is never happy. Was she really wearing that? Where did she even get that? Did you see her hair. Maybe if she did something with that face. If she was. If she wasn’t.

I like Henry James fine, for the record.

September 19, 2014

pleasure principles

Christopher Beha’s essay “The Death of Adulthood in American Culture,” in which Scott ultimately seems to be lamenting (as far as this humble reader is able to parse) that “The elevation of every individual’s inarguable likes and dislikes over formal critical discourse, the unassailable ascendancy of the fan, has made children of us all. …grown people feel no compulsion to put away childish things” (including, obviously and most egregiously, young adult fiction).

“It seems that, in doing away with patriarchal authority,” Scott writes, “we have also, perhaps unwittingly, killed off all the grown-ups.” Both pieces cite the literary critic Leslie Fiedler, author of the 1960 book Love and Death in the American Novel, which asserts—according to both Beha and Scott; I haven’t read it, and don’t care to—that “the great works of American fiction are at home in the children’s section of the library.” Scott quotes Fiedler further, in what he identifies as a “sweeping (and still very much relevant) diagnosis of the national personality”: “The typical male protagonist of our fiction has been a man on the run, harried into the forest and out to sea, down the river or into combat — anywhere to avoid ‘civilization,’ which is to say the confrontation of a man and woman which leads to the fall to sex, marriage and responsibility. One of the factors that determine theme and form in our great books is this strategy of evasion, this retreat to nature and childhood which makes our literature (and life!) so charmingly and infuriatingly ‘boyish.’” More about that in a moment.

In his own essay, Beha distinguishes between “books that have the Y.A. label slapped on them purely because of their subject matter” (teenagers, presumably, although he does not elaborate) and a label that is “sometimes wielded to make a real literary distinction” between Actual Literature and books that involve “simplifying things—first the diction and syntax, but finally the whole picture of life.” This thesis, wholly unsupported by any examples of either category, conjures up the somewhat hilarious image of an editorial meeting—doors closed, shades drawn, editors holding aloft the next season’s titles and furtively hissing “SIMPLE” or “NOT SIMPLE”—but it leads Beha to one of the most telling conclusions of his piece: in the case of Actual Literature that is sold as young adult, he writes, “the label is simply a marketing tool, which isn’t something that a critic ought to be paying attention to.”

With all due respect, I beg to differ. The only actual young adult novels Beha cites are the exhaustingly ubiquitous The Fault in Our Stars and Suzanne Collins’s Hunger Games trilogy, which suggests both a wholesale unfamiliarity with young adult literature in general and a certain lack of effort undergirding any arguments lambasting it in particular—but my point here is not to defend young adult literature specifically, which has a great many erudite, dedicated, and brilliant advocates, but instead to note that the distinction Beha is making—and perhaps would have realized he was making, had he paid a little more attention to “marketing tools”—is not between young adult and adult literature, but between commercial and—for lack of a better word, though I am well aware of its limitations—literary fiction in general. A cursory survey of the current New York Times hardcover bestseller list for adult fiction, for example, reveals that it is topped by a novel about an escaped sniper with nearly superhuman powers who must be stopped by a retired military cop accompanied by a (presumably young and buxom, though to be fair, I’ve never heard of the book) Zoloft-popping lady rookie analyst. Serbian thugs are thwarted, a dead girlfriend from the past haunts our protagonist, crosses are doubled. Very mature, I’m sure. If there are any sweeping generalizations to be made about what Beha identifies as “our larger cultural moment” (and oh! What a problematic and freighted “our” that our is; who is to be included in this “we”? ), it might be worth looking past the inexplicable current pop-critical focus on the saccharine perils of young adult fiction and pulling the lens a little wider yet.

Both writers are preoccupied with the decline in influence of the Straight White Male—the news of which, I must admit, came as something of a surprise, but then I am female, and thus limited in my perspective. “If we really are living through the decline of the cultural authority of the straight white male, that seems like a rich and appropriate subject for a sophisticated work of narrative art,” Beha notes, which suggests that he is not familiar with any literature by white men published recently at all. He does not like Donna Tartt (whose presence in this essay is somewhat inexplicable, but okay), writing off The Goldfinch as “boring,” but if any major book of the last decade deserves that contemptuously lazy and offhand dismissal, I would argue it is instead Jonathan Franzen’s Freedom, a tired retread of Madame Bovary so obsessed with the Decline in Influence of the Straight White Male that it neglects to at least borrow any of its source material’s brutal wit, malicious joy, and devastating insight into the horrific banalities of white middle-class life. At any rate, while I suspect that rumors of the decline in influence of the straight white male have been greatly exaggerated, I personally cannot imagine any subject less interesting for a work of art.

Ultimately, though, it’s the idea of adulthood I’m interested in here, and in what adulthood seems to mean to these critics who have secured pulpits in two major media outlets bidding it a wistful farewell. Both Scott and Beha quote Fiedler uncritically, which is, more telling than any other point made by either of them—and, I think, far more awful: the unquestioned assumption that adulthood consists of sex, marriage, and responsibility (“One Man One Woman”: there are already bumper stickers) is—well, you don’t need me to tell you what it is.

The idea that pleasure should be relegated to adolescence seems a dreary recipe for adulthood indeed, but whose pleasure, exactly, are we discussing here? What of people who have been persecuted solely on the basis of their pleasures, for daring to be joyful in bodies regulated and punished for those pleasures by the apparatus of the state (let us not forget that Michael Brown was “no angel,” let us not forget Islan Nettles, beaten to death for the crime of living in her own body, let us not forget—but the litany of names of people who have been murdered, imprisoned, beaten, made homeless, is so long my heart aches even trying to pick out representative examples)? What of those of us for whom pleasure is not an act of regression but an act of survival, a form of resistance, an insistence that our lives, our bodies, our loves be recognized even as we are asked every day to recognize the lives and loves and bodies that are canonized exhaustively in the “adult” literature Beha and Scott champion? Are we denied, then, the dignity of “adulthood”? If "adulthood" is defined as hard (unpleasant) work, marriage, the assumption of heteronormative middle-class values—what does that leave those of us who have constructed lives of our own so far outside those systems of value and exchange that they seem to us almost a foreign country for which we have been denied—and may not even wish to own—a passport? Is it not too much to ask that we be allowed our own literature, our own canon, our own heroes and (gasp!) heroines defining lives for themselves outside the bounds of patriarchal norms, or even entirely indifferent to them?

“Putting down ‘Harry Potter’ for Henry James is not one of adulthood’s obligations, like flossing and mortgage payments; it’s one of its rewards, like autonomy and sex,” Beha concludes. Let us leave aside for a moment the staggering thesis that Grownups' Books, sex, and autonomy are reserved solely for those who have reached the drinking age (voting, maybe? The exact line of demarcation between Child and Adult is never made clear); for what it’s worth, I first read—and enjoyed—Henry James when I was seventeen. To paraphrase Beha, it seems not to me embarrassing or shameful but just self-defeating and a little sad to insist that the pleasures of difficult fiction cannot possibly be enjoyed by a child. But more importantly, I find it utterly dangerous to blithely assume that an exclusively heteronormative and classist construction of adulthood is the bar by which all our literatures and all our lives ought to be measured—those, sirs, are fighting words, and I’ll see you at the mat. You may rest assured I am not in decline.

September 12, 2014

muscle memory

The weather changed & my heart changed with it; I am one of those people who is glad for fall, glad always, glad as my whole life opens up again & I remember what is possible & all the things I want to do.

It was, for the most part, a hard summer. I am running forty miles a week, a thing I would not have thought doable very long ago, before a few weeks ago, before I did it & realized I could. I was trying to explain to someone how this happened, how my body became a body that is capable of this doing, & I said I think it is mostly a matter of scale. Of how your perspective changes when the undone thing becomes done.

I am tired of trauma & of writing about trauma & of the idea that trauma is the only experience women have to offer the world, the only piece of our lives that matter, the only story we have to tell (over & over & over & over), tired even as these stories repeat themselves ad nauseam in the public eye, even as trauma is reproduced endlessly & in a thousand novel ways, trauma against all bodies othered and queered, all bodies brown & black & female & trans, that even as trauma metastasizes & our naming of it is met with refusal, our demand that it be recognized is turned aside, trauma is still the only story that is given to us to tell.

We do other things besides bleed. We fight and set fires, we build communities, we love in the face of all that does not love us. We knit bright clothes out of shrapnel. We drink on railroad bridges under the broad white moon & name all our dreams in order, one by one, the train cars passing behind us so close they’d shear us clean through if we leaned back too far. We tattoo one another’s names with needles & India ink; we make our memories into our skins. We make lives. We make living.

I am working on a book about monsters & I have been afraid of it for a while. I look at the notes, the blank document, put them away, do it again. Do we want to go back to those places? Is it worthwhile? I don’t know. But the story keeps calling my name. A friend of mine who used to be a distance swimmer told me that she had fallen once from a great distance & when she went to the hospital they told her she had shattered her spine but her muscles were so massive they held the splinters of bone in place, that that was what saved her, her own strength born of practice. We spend all our days making muscle for this. We run and run and run until distance is only a matter of time.

Sarah McCarry's Blog

- Sarah McCarry's profile

- 156 followers